CHAPTER 9

PULL IT ALL TOGETHER

A book should serve as an axe for the frozen sea within us.

—Franz Kafka

I like shape very much. A novel has to have shape, and life doesn't have any.

jean Rhys

In Chapter 4, you explored which genre you would write in. Chapter 5 guided you to select your concept, Chapter 6 to turn bits of people from your life into compelling fictional characters, Chapter 7 to distill life into plot, and Chapter 8 to select and transform places you've been or locations you've researched into cinematic settings. Now it's time to connect all those pieces and build your novel. This step is normally scary, but if you've been completing the writing exercises in each chapter, you have everything you need to soar.

I wasn't so lucky when I started my first book or my second or even my third. If I'm honest with myself (and you), it's not exactly ancient history that the idea of drafting a novel felt like being dropped into central Africa's Congo Basin with a compass and a paperclip.

Naked.

Rolled in honey.

With everyone I've ever wanted to impress watching via a live feed, gathered together in a room, eating popcorn and laughing so hard that they spewed schadenfreude all over the television.

When I began drafting May Day, I spent much of my writing time feeling overwhelmed at the scope of what I'd taken on and like a ridiculous fraud for even pretending I could write a book. I grew up in rural Minnesota, for crying in the night. Not only did I not know any writers, I hardly knew anyone who liked to read.

But there was personal treasure to be mined in the writing of a novel; I sensed it even then, rubies of resilience and emeralds of hope, and so I read what I could on the craft of writing, sought out mentors, and read fiction like a chef trying to puzzle out the recipe by tasting the meal. After five years of trial and error, I finally arrived at a method to reduce the time and stress of crafting an experience-based novel while increasing the joy of writing and the quality of the story.

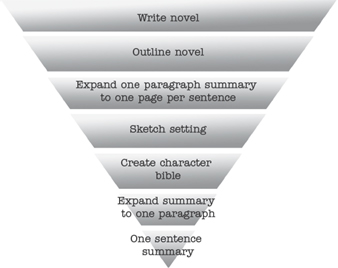

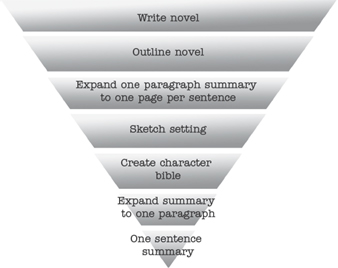

I call this technique the Pyramid on Point (POP) method because it balances the entire novel-writing process around the tip, or the point, of your idea. All writers end up with a unifying theme across the books that they write and that theme is the most indigestible nugget in their mental compost pile.

For example, I write about the poison and power of secrets. In. Every. Single. Book. While it took writing eight novels to realize it, I come by this meta-theme honestly. I grew up in a house built on fear and secrets, liberally sprinkled with alcoholism, psychedelic drugs, swingers, and naked volleyball parties. I saw enough dangling wieners and bouncing boobs in the '70s to last a lifetime. I packed my first bong before I was ten and mixed a mean whiskey water by age twelve. To this day, I think my mom and dad's worst fear was that I'd rebel and turn Republican. My parents will be mortified to discover I am writing about them or my childhood. This, along with an instilled allegiance to secrets, has kept me from writing nonfiction up until this moment. How am I finally breaking free of this, you ask? The advice to write as if your parents are dead seems too harsh. I'm instead electing to write as if they're illiterate.

My experience of sifting through my mental compost pile via novel writing is not unique. At a recent writing conference, a famous dominatrix and successful noir author confessed to me that all her books are about that pivotal, cathartic moment when a person tests their limits. Many of John Irving's novels contain a recurring theme of younger men who are seduced or abused by older women. Parental abandonment appears in every one of Charles Dickens' books. Amy Tan tackles mother-daughter relationships in her stories. You will find some version of your own experience-based theme in all the novels you write.

As covered in Chapter 5, “Choose Your Novel Concept,” you'll find that most if not all your ideas are already hiding, ready to be plucked, in the compost pile of your mind. Remember that your compost pile is that fertile, loamy, shit-filled place where you tossed your baggage in the hopes that it would decompose on its own. It doesn't. You have to stir it up and spread it out. It's just the way it works.

Don't worry if you don't know your life theme right now; discovering it is one of the many gifts of novel writing. What I need you to do now is take your hottest idea and work it through the POP method that follows. This method leads you through seven manageable steps that transform your life experiences into a novel, regardless of how much writing experience you've had. Because of the work you've begun in the previous chapters, you already have a good base for your characters, plot, and setting. Now it's time to pull it all together and write that book. Grab your journal and pen, because here we go.

STEP 1: FIRST, SUMMARIZE YOUR NOVEL IN ONE SENTENCE

Open a new page in your journal. If you didn't already do this in Chapter 5, distill the overarching concept of the novel you will write into its purest form: a single sentence. Don't include specific names or places now; the idea is to be purely conceptual.

I'll use a work by one of my favorite authors, Isabel Allende, as an example. Allende is no stranger to converting her pleasure and pain into best-selling novels. As I wrote earlier, The House of the Spirits, her first book, entered this world as a letter she was writing to her dying grandfather.

At the time, Allende was in exile from her home country, unable to visit her grandfather, and struggling with deep grief. In a Washington Post interview on the writing of The House of the Spirits, she said, “I had lost everything I had. It was a crazy attempt to recover everything . . . in those pages.” She instinctually drew on and fictionalized her rawest pain, cloaking her specific experiences in imagination and weaving them together to craft a lush, evocative novel that became an international bestseller, award-winning movie, and popular play. Here is what Step 1 of the POP method would look like for The House of the Spirits:

Standing in for Chile, patriarch Esteban Trueba grows from child to elder, struggling against and then embracing the revolutionary flow of life.

Notice how that sentence is neat and sweet? It's tempting to pack lots of detail into your one-sentence summary. Your idea is complex, your characters multifaceted, your setting diverse. How can you condense all of that to a handful of words? Remember my Chapter 5 example, my brain-dump crack at what Eve, the magical realism novel that I'm writing simultaneous to this book, will be about?

The year is 1907, and seventeen-year-old Eve Catalain has arrived to Faith Falls, Minnesota, along with the quarter-century rising of the snakes. As beautiful and elusive as a firefly, she has captured the eye of Crucifer Darkly and Ennis Patterson equally. Crucifer is wicked and wealthy, the source of dark rumors, respected to his face and feared behind his back. Ennis is twenty years older than Eve, quiet, kind, and wretchedly content to be her friend. When Eve defies Crucifer's command to never enter his mansion at night, she uncovers a secret the town would kill to keep hidden. How she responds will either cement her personal power or curse generations of Catalain women to come.

Besides being far too long, this summary includes extraneous detail that is important to me but not crucial to the task. Again, the goal is to take an aerial snapshot of your novel, capturing only the large structure. If you search online for “New York Times bestseller list,” you'll find an excellent example of this type of concise description accompanying each book on the list. Trim your initial vision so your sentence is as succinct as those descriptions. After I cut away the subplots, supporting characters, and superficial detail, I am left with this one-sentence summary of Eve:

Seventeen-year-old Eve Catalain must learn to trust in her own power when she uncovers the terrible secret binding the people of the not-quite-right town of pre–WWI Faith Falls, Minnesota.

If you craft this sentence with accuracy and poignancy, it will feed you during the lean times of self-doubt, be your northern light in the writing process, and, if you are so inclined, give you a snappy line to share with friends and family who ask what you're working on. Once you're satisfied with your sentence, it's time to move on to Step 2.

STEP 2: EXPAND YOUR SINGLE SENTENCE INTO A ONE-PARAGRAPH-SUMMARY

Step 2 is a summary of your entire novel and should be written in your journal immediately below your Step 1 sentence. Summarize the status quo at the opening of your novel, what obstacles the protagonist encounters, and how the novel ends. This isn't the time for secrets. Lay it all out.

Refer to the writing exercises you completed in Chapter 7 for this step. If it is helpful, freewrite or mind-map even further, using key names or phrases from your Step 1 sentence as your launch point. Based on my one-sentence overview of The House of the Spirits, for example, I would write “Chile,” “Esteban Trueba,” and/or “revolutionary flow of life” onto the top of a clean sheet of paper and free-write for ten minutes, penning anything that came to mind without pausing to criticize or proofread. As you know, you'll be amazed at the insight you can access through freewriting.

Once you have a solid idea of the major plot points of your novel as a result of what you read in Chapter 7, freewriting, mindmapping, or any other tool that works for you, write your full paragraph summary. Here is that Step 1 single-sentence summary of The House of the Spirits expanded into a full paragraph (spoiler alert in case this book, or the Meryl Streep film that came after it, is new to you):

The book opens with sisters Clara and Rosa del Valle living in a fictionalized Chile. Clara, an avid diary-keeper, is able to see the future. When Rosa is accidentally poisoned, Clara takes her place as Esteban Trueba's wife. In the interim, Esteban had gone from a poor miner to a wealthy but often cruel rancher. The first woman he rapes, Pancha, becomes pregnant with his son. His wife, Clara, bears three children. The oldest, Bianca, falls in love with Esteban's foreman's son, and the second third of the story is devoted to their forbidden romance. When Bianca becomes pregnant out of wedlock, Esteban whips Bianca, strikes Clara, forces Bianca to marry another man, and cuts three fingers off the father of her child. The final third of the story is devoted to Alba, the illegitimate child of that relationship and the only one who still speaks with Esteban. Alba falls in love with a revolutionary named Miguel, who was present at her birth but whom she hasn't seen since. The grandson of the first woman Esteban raped is now a military leader, who kidnaps, tortures, and rapes Alba, bringing the cycle started by Esteban to a close. Esteban helps Bianca and the foreman's son, both of them now middle-aged, to escape prison, frees Alba, and dies in Alba's arms with Clara's spirit as a witness. The book ends with Alba promising forgiveness and writing the book that becomes The House of the Spirits.

Breathtaking, right? And because of the seamless paper wall that fiction provides its writers, we don't know which of the above story threads are plucked whole from Allende's personal struggles and which are purely products of her imagination. Ultimately, not only is it not any of our business, it also doesn't matter. The only thing that counts is that Allende drew directly from her well of challenging life experiences to craft a complex novel. Writing from her truth healed Allende, as she states in a 1989 interview with William Zissner:

In the process of writing the anecdotes of the past, and recalling emotions and pains of my fate, and telling part of the history of my country, I found life became more comprehensible and the world more tolerable. I felt that my roots had been recovered and that during that patient exercise of daily writing I had also recovered my own soul. (44)

A bonus? Her authenticity, earnestness, and vulnerability made this book an international bestseller.

Of course, Isabel Allende didn't use the POP method when she wrote The House of the Spirits, and she certainly didn't have that summary of her own book. She simply typed for a year until she wrote five hundred pages that looked an awful lot like a novel. You can select that route, too, but I find that structure makes the novel-writing process less daunting. For that reason, I suggest that before you draft your book, you come up with a one-sentence summary (Step 1) and expand that sentence into a full paragraph that touches on the main plot points of the book (Step 2) like I did for The House of the Spirits.

Note that you must give away the ending to make this Step 2 paragraph work. This summary is for your eyes only, and it's dynamic. You'll find yourself returning to tweak it as you continue, and that's okay. You're writing a book, not a contract. Revising as new ideas occur is one of the exciting elements of writing.

Now comes my personal favorite step.

STEP 3: INVITE YOUR CHARACTERS IN

Now is the time to expand your sourcebook, or character bible, profiling each of your significant characters.

I usually handwrite my character bibles in journals I now create for each novel, but a computer works just as well. If you use writing software like Scrivener, you'll find premade character templates at your fingertips. Devote at least a page to each character, drawing from the cast that began to populate your budding story as soon as you nailed down your concept in Chapter 5 and that you expanded on as you explored your characters in Chapter 6. Include the following information if you haven't already:

- Name and photograph. The photo is optional, but if you come across a picture of someone in a magazine or newspaper or an old family photograph that reminds you of your character, slipping that photo into the character's page works wonders to spur creativity and flesh out characterization. For example, I intend to include a photo of Kathy Bates as Misery's Annie Wilkes in my character bible for Eve. Her psycho nurse looks very much like Aunt Bea, the babysitter who locked my sister and me in the closet and let her son perform terrifying puppet shows for us, and I'm going to include her as a character in flashbacks to her early life to flesh her out and build sympathy for her.

- Physical characteristics. This includes the basics of height, weight, hair and eye color, and so on. This information is particularly useful for characters who won't appear a lot or who will show up across a series. Because you've compiled these details, when these characters do pop up, you'll know just where to look for a physical description of them. Remember to think physically quirky, too.

- Age. Include the actual birth date if it's relevant.

- Personality traits and their source. For example, is a character lazy because their mother always picked up after them? Do they love baseball because it's the only game their father ever played with them? Do they try to control every person in their life because their childhood lacked stability?1 Are they steadfast, honest, outgoing, introverted, a space cadet, moody, and if so, why?

- Quirks and coping mechanisms. These are one or two imperfections that make your character human, such as a tendency to hum when nervous or a snaggletooth that makes them reluctant to smile.

- Goals and motivation. Ask yourself what your character wants and why they want it. Put your own heart and secrets in here, as outlined in Chapter 6.

- Conflict. List the obstacles, large and small, that the characters face in achieving their goals.

- Growth. This is also called the character arc. How is this character going to be different at the end of this novel? Is their worldview changed? Their heart opened? Think about how you would like to change as you brain-storm this section, because as your protagonist grows, so grow you.

Remember that as their creator, you always need to know more about your characters than your reader ever sees. This inside information allows you to create a multidimensional, internally consistent population for your novel, but you're not going to dump it all into the novel any more than you'd share every detail of your own life with someone you just met.

Be aware that the character bible is an easy place to get sidetracked; keep your character outlines to one or two pages per person so the process doesn't morph from novel writing to scrapbooking. Also know that this step may be an emotional trigger because you will be digging deep into human motivation as well as the consequences of human choice. Take breaks when you need to and remember that you control the pace, rate, and direction of everything that happens to the characters in your story.

STEP 4: SKETCH YOUR SETTINGS

Building on what you learned and practiced in Chapter 8, draw the street layout and the interior space(s) where most of your story will take place. You will likely have several sketches.

You will find that, like your characters, your setting naturally follows the life challenge you chose as your novel-worthy concept in Chapter 5, “Choose Your Novel Concept.”

No fear when you get to this step; you don't need to be an artist to handle it. If you're sketching a room, for example, just chicken- scratch the major pieces of furniture and placement of windows and doors, as well as which direction is north. If your book is set mostly in a neighborhood or town, sketch out the relevant cross streets and scribble labeled boxes where you imagine all the businesses and houses would be. Obtain an actual city map if you are setting your novel in a real location so you can reference street names and landmarks.

The setting sketches anchor your writing and create consistency and plausibility. Also, they are crucial to writing cinematic action scenes, whether your character is being chased through the alleyways of New York's Meatpacking District or throwing punches in a living room as the furniture splinters. If you have space, staple in a photo or two if you come across an image that captures an element of your setting, and use Google Earth and other online research to fill in any details your memory cannot.

STEP 5: DEVELOP EACH SENTENCE IN STEP 2 INTO A FULL-PAGE DESCRIPTION

Include at least two sound, two smell, and two touch details on each page. For example, let's take the first sentence of The House of the Spirits summary that I created in Step 2:

The book opens with sisters Clara and Rosa del Valle living in a fictionalized Chile.

If I were to expand this to one page, I would describe the characters' features, the smell and flavor of the country, the feel of wind or sun against their skin, the clank and clamor of the countryside. I would include preliminary research into the political issues, mores, and technological breakthroughs of Chile during that period so I could insert accurate conversational topics and make sure I got the clothes and hairstyles just right. I'd brainstorm and roughly outline the give-and-take that would occur if two sisters were talking about a man one of them was going to marry. Use your journal to explore and develop every sentence of your own summary in this way.

STEP 6: COMPLETE A ROUGH OUTLINE OF THE NOVEL

Remember the words of Robert Frost: “No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” A chapter-by-chapter, detailed outline simply isn't for everyone and might restrict or sap your creative drive when it comes time to actually draft the novel. Instead, generate a rough outline that highlights only the major conflicts and character interactions, essentially a more complex version of the summary you completed in Step 2. This big picture outline allows you to always have something exciting to write toward without eliminating the joy of discovering what your characters will do when left to their own devices.

I've created a template, located in Appendix F, to help you outline your novel and break down your writing schedule into manageable steps. If it's useful, plug your information into the template and go to town. If this kind of left-brain planning drives you bananas, however, consider yourself in good company. Approximately half of all published writers are called “pantsers,” or writers who prefer writing by the seat of their pants rather than outlining. If this describes you, complete these first six steps in a fashion that feels more organic, planning to spend approximately four weeks on them before beginning the next step (Step 7, “Write the novel”).

If, like me, you need the comfort and backbone of structure to really nail the story, I encourage you to use the template. I've filled out the first eight weeks of it below for Eve so you can see what it could look like. In my example, I have scheduled four weeks to finish the POP machine and eleven weeks to write the first third of the book. Notice that during several of those weeks, I chose to write multiple scenes. The system is set up so you can write one scene (approximately fifteen hundred words) a week and finish your novel in a year.

Also notice that I've included emotional memory and experiences that I'll be drawing on in writing each section. They're italicized in the table. Including these scene-level inspirations/models is crucial to writing with authenticity and heart. Other components of this template include

- Where I save my work. While I do all of my pre-novel work—essentially everything you've read in this book up until now—in a journal, I do the actual writing on a computer, and I save it in at least two different spots. I recommend you do the same so you never lose your work.

- What I'm reading as I'm writing because reading fiction inspires the writing of it.

- The fabulous but sometimes sucky ideas that inevitably strike as I embark on a creative venture.

- Roughly, which act the scene falls in, using Campbell's three-part departure-fulfillment-return structure.

- This one is big: how I treat myself when I reach a goal. Absolutely vital to the whole shebang. The process of writing itself is rewarding, but it doesn't always feel that way when you're sweating away in the fiction mines. Figure out what feels good—chocolate, bubble baths, a weekend in the woods—and make sure to tie rewards to commensurate work. I recommend a free, healthy reward for daily writing. I like to walk outdoors or watch my favorite TV show when I meet a daily reading or writing word count, for example. Save the big rewards, the ones that entail costs or calories, for big achievements, such as completing the POP method or drafting your novel's first act. Incorporating rewards is crucial to creating a work ethic but also to giving this undertaking the sense of adventure and excitement it deserves.

The blank template in Appendix F includes spaces for you to schedule the writing of your entire novel, not just the first act. Also, that template includes three weeks for the editing phase. More to come on that.

STEP 7: WRITE THE NOVEL

This is it. The training wheels are off. You now have a snapshot of your novel and a rough map for creating it. You know which characters are populating your story, what they'll face, and in what locations they'll face it. Write one scene a week for forty-five weeks, each scene approximately seventeen hundred words, and you'll finish a complete first draft in less than a year.

Creating the first draft of your novel really is this straightforward—and the results are undeniably powerful—when you break it into these seven manageable steps. Using this method not only reduces much of the anxiety inherent in writing a book but also allows you to work out most of the snags and missteps from the get-go so you don't waste words or time when it comes to digging in and actually drafting the novel.

Remember to be gentle with yourself throughout. Also, watch for this Easter egg as you write truth-based fiction: because you are consciously organizing your crucible moments, you will find that you're buying yourself perspective and a precious few seconds to choose new reactions to old triggers. How cool is that?

As you write your novel, continually draw on the emotions and experiences you mined in Chapter 5, “Choose Your Novel Concept.”

Take me. The odds are good that being raised in a home of debauchery and secrecy coded me for my later mistakes. It attuned me to look past outward signs of success and stability to locate the deeply wounded. Essentially, I was a long-haired Burden Retriever, hard-wired to sniff out the unhealthiest person in the room to love and fix. Writing fiction based on my own experiences has bought me the self-awareness and safe space to instead heal myself. As a result, I no longer respond as readily to those childhood markers. Rewriting my life has also bestowed upon me a gnarly gratitude for the deepest of my wounds. How shallow would I be without them?

Rewriting my life didn't function as an on/off switch for learned behaviors but rather as an opportunity to choose based on who I want to be rather than what had happened to me. And who knows? When I finish writing Eve, I might even get to graduate to a new theme.

I wish the same for you, that by rewriting your life, you get to choose the theme that defines your journey on this earth. Use this chapter's seven steps to give you the necessary psychic distance from your story and create a safe, efficient structure for accessing the transformative, evocative power of writing fiction from your personal truths.

BONUS STEP

If you finish the first six steps of the POP method and still feel as if you're not quite ready to fly, try backward outlining the first three chapters of another novel. Any novel will work, as long as it is in the genre you'd like to write in. Let's say you want to write literary fiction, and so you select The Secret Life of Bees. Peel back the specifics—character, setting, time period—to reveal the rhythm of the story. This is what a backward outline might look like for the first three pages of that novel:

- Main character and three lines of setting on first page.

- Interaction between antagonist and protagonist on second page.

- Humor and foreshadowing on third page, followed by flashback.

- Inciting incident on fourth page.

And so on. After you create a backward outline of the first three chapters, slap your characters, setting, and time period onto that rhythm. Introduce your main character and describe your setting in three lines on your first page. On your second page, have your antagonist and protagonist interact. Once you have the structure of the first three chapters down, you're ready to sail.

One warning: make sure the central plot of your story is different from the novel you're backward outlining. For the first thriller I wrote, I backward outlined the first three chapters of The Da Vinci Code and slapped my own story onto that structure. My agent made me dramatically rework the first hundred pages. She said it was too much like The Da Vinci Code.