The Twenty-first-century Workplace Navigator

We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road.

C.S. Lewis

Coming from an island-nation, I have always been fascinated by the sea and seafaring and have admired the men and women who embark on long sea voyages across the oceans or circumnavigate the globe. The sheer tenacity they display negotiating extreme challenges by using their wits and skills to battle the elements and the determination they show by overcoming every difficulty to reach the safety of their final destination is awe-inspiring.

I was fortunate enough to work with Nick O’Donnell, who not only sailed around the world, but was also another fellow traveller in helping me translate the property strategy for the BBC’s White City campus. Nick had also done stints as EMEA Head of Corporate Real Estate & Facilities at Microsoft and is currently at the helm of the University of London’s King’s College estate. Working with Nick and hearing about his adventures on the high seas, where he faced and coped with obstacles on board, certainly inspired me to view my journey at the BBC in nautical terms.

Being in that leadership role, in which I was figuratively the captain of the BBC’s property transformation, I felt like I was steering a ship, especially the moments of self-doubt and outright frustration when the team struggled with the relentless pressure and were unable to perform to their utmost ability. It also taught me that it is lonely being at the top and having to skipper the course through some pretty ugly storms; when the terrain was tough, the maps let me down and the incessant pressure felt like a constant downpour. Yes, at times I did feel like I was very close to a Titanic iceberg! However, the sense of fulfilment, achievement and pride I felt for all the crew when the sale of Television Centre in West London was complete was tremendous, once this mega-project had reached its ultimate destination – it also marked the end of my ten-year BBC journey.

With Nick’s input into shaping the nautical narrative, I hope to help leaders and decision-makers in their journeys across the treacherous waters of today’s unpredictable business environment. The solutions I am proposing may not be a panacea to every problem, but at the very least they should provoke management to consider taking a fresh view in how their organizations use offices. A view that is more holistic in its approach, underpinned by the human dimension and conscious that it can add value to the business, while also becoming more sustainable.

Developing this set of tools prompted me to extend my thinking to consider life beyond the status quo of the existing model for providing and consuming real estate. The results of my analysis ‘New Horizons’ conclude this chapter as a challenge to both sides of the equation to think ‘outside the box’ as I believe this could well lead to better outcomes for all parties.

Charting the Route to a Great Workplace

In developing this framework I have worked with my workplace ‘partners in crime’, HR supremo Caroline Waters and Max Luff from Six Ideas, plus a range of collaborators in this somewhat rarefied field. We belong to a very small group of thinkers who can transcend the rigid and formulaic world of real estate, design and facilities to connect with the world of business, the workforce and indeed the wider community, which extends to the economy.

Figure 5.1 below proposes a five-step process which provides some suggestions as to how to create great places to work. It charts the broad bones of a process that could help organizations benefit from harnessing an effective workplace, one that meets the demands of operating in today’s business world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity.

FIGURE 5.1: The Journey to Great Places to Work

I have found that most leaders need a highly tailored approach, which can be customized to suit their particular set of challenges, which have to be dealt with at a specific point in time. One also has to keep other factors in mind too, such as the particular organization’s life cycle, the composition of its leadership cadre and the appetite of the CEO to personally drive change.

What this route provides is a set of charts for organizations to follow either in their entirety or just by dipping in and using some elements. This is not a detailed step-by-step manual nor is it a specification, but a guide to be adapted by management to fit in with their particular enterprise and its demands. One important lesson I have learned from my experience at the sharp end is that there is no fixed recipe for success so beware of those who proffer cookie-cutter-type solutions!

Plan Your Passage

A savvy skipper pays careful attention to planning before setting out on a voyage. Apart from the seaworthiness of the vessel and the weather forecast, there are many aspects to consider, such as tides, currents, supplies and number of crew required. So before setting sail to create that great workplace, the savvy leader can be better equipped and better informed of the risks associated with the change voyage.

One might argue that a similar approach is applied when an enterprise contemplates an organizational change or workplace project. However, I wonder how much consideration leaders give to ‘how’ they will achieve these changes? Do many leaders ask themselves questions such as:

• How will we ensure it is successful?

• How are we covering off the risks?

• How will the project deliver the required outcomes?

This is not about examining the ‘the nuts and bolts’ of a project delivery mechanism; what I am advocating is a more contrarian approach. Maybe leaders should ask the project sponsor(s) why things are being done in a certain way? The majority of answers will probably be ‘because that’s how we’ve always done it’.

There is fundamentally nothing wrong with pursuing tried-and-tested methods which have worked in the past. However, if leaders are prepared to build a better understanding of the behaviours, components, factors and practices which form part and parcel of a workplace project they may unlock some hidden benefits such as ways of mitigating risk, avoiding waste and reducing costs.

Having successfully navigated organizational transformation journeys at the BBC and Disney, I have learned that it is very important to have a good grasp of what roles the diverse elements play in the overall structure of the business. By taking a holistic view, I was able to see the big gulfs that exist between the perspectives of the various stakeholders involved in the operation of its facilities and its people. However, when it comes to projects which involve work, the workforce and workplaces, there are a host of variables which are poorly understood by one or more of the stakeholders. Many leaders are unaware of the gaps of understanding that exist in the system which produces and operates today’s workplaces. Understandably, management also place their reliance on the views of their team, who may also be unaware of these gaps. Then, when things go awry or fail to deliver the required benefits, everyone is left wondering why.

When it comes to these gaps in understanding, they always remind me of the warning announcements on the London Underground – mind the gap! – alerting travellers to the gaping hazardous space between the platform’s end and the entrance to the train. So alerting business leaders to ‘mind the workplace gap’, I have pinpointed the six areas in the ecosystem of real estate and the workplace which impair and negatively impact projects, increase friction within their operation and incubate risks that cause significant problems to the extent that these gaps of understanding are a lost opportunity. I have labelled them ‘The Chasm of Misunderstanding’ in Figure 5.2, below.

FIGURE 5.2: Six Bridges

As I discussed earlier, I contend that due to the fragmented nature of the real estate ecosystem all the key stakeholders have different perspectives on the situation. Currently all the players have as their primary focus the twin factors of cost and efficiency. To cite EQ Office CEO/President Lisa Picard, ‘We are still managing business and real estate using metrics from the machine age when we thought about humans in the same way as machines who needed to be housed efficiently in order to be productive. The arrival of knowledge work has changed all this.’ Plus, we have the two sides of the supply–demand equation with diametrically opposite perspectives. For example, business views the real estate sector with disdain while the supply side sees business as just another tenant who pays the rent. Therefore, I suggest the key to creating a great place to work is to invest some time and effort in building ‘Bridges of Understanding’ to span the chasms in these six areas (see Figure 5.3, below). This can be achieved by understanding the overall context of how the system works, including the delivery process for the workplace, the silos that exist and, above all, the differing mindsets involved.

FIGURE 5.3: Six Bridges Spanning the Chasm of Misunderstanding

Building a bridge of understanding between each of these six areas will deliver a range of benefits not only for an organization’s leaders, but for all the stakeholders involved in the provision, operation and support functions of the workplace. However, it is pivotal to expand the discussion beyond just cost and efficiency to business value and effectiveness. The first step is recognizing the nature of the link between the two sides of the chasm and why there is a gulf between the two entities. It is also worth analysing the potential benefits of bridging the gap between these disconnected features.

The Six Bridges Spanning the Chasm of Misunderstanding

• Bridge 1: Customer – Landlord/Developer

When one comes to consider the production and consumption of office buildings, a place which 61.5 million people in the US alone use on a daily basis; it is incredible to think that for the most part there is no direct relationship with the occupiers apart from the lease contract. This lack of a connection between the landlord and tenant prohibits the creation of a true relationship with the customer/end-user.

There are exceptions to this state of affairs, but for the vast majority of real estate markets around the world this status quo persists. There are ways and ideas which the industry could adopt to try and build new and better types of customer relationships, which could benefit both landlord and tenant;

• Bridge 2: People – Place

It really is all about people and their ability to access their choice of tools and spaces, which allows them to do a good job in the best way possible. People need to feel that they can be productive, but the organization also needs to believe that the workplace has motivated them.

For those of us involved in the workplace sector this makes sense, but many people do not understand this correlation. However, this thinking should enable the enterprise to maximize creativity, collaboration and engagement while fostering a desire to learn and grow;

• Bridge 3: Efficiency – Effectiveness

Efficiency and effectiveness reflect two sides of a set of ‘terrible twins’. They are inextricably linked, share many common attributes, yet generate different outcomes. Although like twins they seem similar in many ways, the relationship between them is not well understood. As efficiency is the easier of the two to quantify and measure, most stakeholders focus on that side of the equation. I have also seen evidence where efficiency is mistaken for effectiveness. Yet overall, it is the effectiveness aspect that is more valuable and what few people realize is that both sides are required in tandem to navigate towards a great workplace. One needs to facilitate both the efficiency and effectiveness factors to steer your crew;

• Bridge 4: Enterprise – CRE/FM/HR

The way organizations engage with their internal support teams, who are responsible for their real estate portfolio, facilities, technology and human resources, is crucial to bridging this particular gulf. These groups, whether unified or disconnected, need to be challenged or encouraged to move from being mere order takers, process managers and dealmakers to provide much greater strategic support for the enterprise.

On the flip side, senior management need to empower and equip these teams to operate strategically to add value to their business. As discussed earlier, facilities services have seen justifiable cost-cutting over the last few decades. This has resulted in a downwards spiral into providing mediocre and fragmented services.

These three groups, CRE, FM and HR, need to be challenged to shift their focus to demonstrate a ‘value for money’ service and to become better enablers of work within twenty-first-century organizations. In parallel, there are also benefits to be had from partnering with Procurement to help them understand how to support the strategic aspects of workplace provision. Overall, the key outcome is to reduce ‘friction’ in the workplace, thereby improving productivity;

• Bridge 5: Client – Service Provider

Over the last 20 years businesses have been outsourcing and off-shoring services extensively. The prevailing mantra of any savvy enterprise seems to be retaining its core activities and subcontracting the rest. When it comes to the workplace sector this has been central to the way most companies have been operating, whereas it is not a bad development in itself – organizations would be better served if there was a rapprochement in terms of the relationships. For the most part they are still based on a ‘master/slave’ arrangement, even though some of these contracts are labelled as partnerships or alliances. I sometimes question if these arrangements are mere window dressing, with both sides paying lip service to partnering.

It would be better all-round if senior management invests time to establish ‘principle-to-principle’ relationships with key supply chain leaders to build a real understanding of stakeholders’ priorities in order to become a truly intelligent client. This is a role for the Procurement team to participate in and help build better understanding and it would also shift the focus to value creation rather than pure cost;

• Bridge 6: Asset – Service

There is no denying the workplace sector is undergoing real change and this is proving really challenging for many players. Therefore, a better understanding of respective priorities and the potential for alternatives should be a way to generate benefits.

It is dawning for some on the supply side that they will have to adjust the model to consider the needs of their customers. However, this does require a two-way dialogue to define a new model which produces gains for both sides.

Benefits Derived from Bridging the Chasm of Misunderstanding

Shrewd leaders should therefore develop a stronger understanding of the discrepancies between these six areas concerning work, the workforce and the workplace. In bridging these gulfs they can derive a range of benefits for their enterprise, while potentially unlocking some innovative opportunities and improving its competitive advantage in the marketplace:

• Higher probability of a successful project outcome;

• Significant increase in staff engagement levels;

• Enhanced ability to mitigate project and enterprise risk;

• Support functions that add to enterprise value, not just cost controls;

• Improved value for money from knowing how to make the best use of an organization’s physical resources;

• Tangible demonstration to the outside world that their enterprise has a coherent grasp of the sustainability and social value agenda.

Set Course and Skipper the Crew

A smart CEO understands the lie of the land of their particular organization as this will inform them of the overall capabilities, appetite and appreciation of what they are trying to achieve. Just like a skipper planning for an ocean racing event, shrewd leaders should consider setting a course that harnesses all the favourable currents, avoids reefs and ensures the crew can set the sails that catch the fastest winds. This not only requires adept leadership but a team which is committed, fit and capable of delivering the task and reaching the eventual goal.

I once watched a sailboat race in the English Channel from the vantage point of a pleasure boat, with yachts similar to the types that compete in the America’s Cup. The sight of these remarkable craft speeding across the waves using only wind power was quite incredible, but what also struck me was how the crews worked together to manoeuvre the vessels. They all worked in complete synchronicity and harmony following directions from their skipper as they adjusted the sails and rigging to take advantage of the direction of the wind. As I watched the race through my binoculars, a phrase I once read sprang to mind, ‘We cannot direct the wind but we can adjust the sails.’ Certainly a useful metaphor for business leaders, no one can control events but how to manage them is well within our power and this can also be applied to adjusting to the winds of change.

Undoubtedly, it is not just adapting to change which is difficult, but also implementing it is even harder. Whether that is effecting transformation in the workplace or in any other generic change initiative, the same challenges exist – how to affect change and make it work. Unfortunately, many are doomed to fail and the business world is littered with numerous examples of unsuccessful transformation projects. According to a much-cited McKinsey report,4 as many as 70 per cent flounder en route and there has been much debate about how to mitigate the risks of failure.

The Key Reasons for Change Projects Failing

• Insufficient executive sponsorship or lack of senior management support;

• Underestimating the complexity of the transformation;

• Employees not involved in the change process;

• Lack of a key person to champion/drive change;

• Not adopting a rigorous and structured approach to the change programme;

• Not breaking down the change process into clearly defined segmented initiatives.

Effecting Organizational Change the Waters Way

When the board of an enterprise sets out a change programme for the CEO to champion, it is presumed that the intent will be delivered. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) will be put in place to measure results and the best project/change management strategies will be applied. This is followed by an appropriate announcement of the transformation initiative to great fanfare, by way of encouraging everyone’s enthusiasm to adopt it. Yet so many of these programmes run out of steam and I often wonder why and what happens since they seem to be set up in ‘textbook’ fashion and yet something goes awry…

The answer to this conundrum came from my friend Caroline Waters, former director of People and Policy at British Telecom, who introduced me to her solution for ‘operationalising strategy’ – the development of a project’s functional strategies and the establishment of its objectives. Her approach – which I call the ‘Waters Model’ – is based on her experience at BT and came from the enormous challenges faced by the organization in the late 1990s. This required the root-and-branch transformation of the ailing telecommunications giant, while reducing its workforce from 265,000 down to around 80,000, while expanding to into 176 countries as it globalized its business.

On his arrival as the CEO in 2002, Ben Verwaayen set the company on course for nothing short of a total transformation. Ben’s aspiration was to break the command and control labour-intensive siloed patterns and build an increasingly collaborative operating model with increased flexibility and responsiveness factored in, by improving communication skills, external awareness and knowledge sharing.

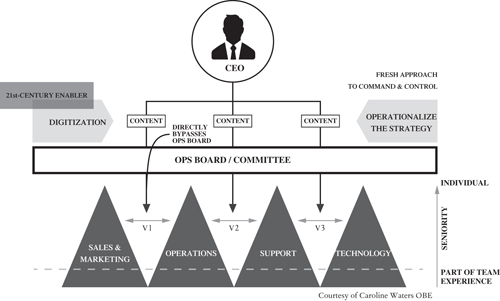

Caroline’s method considers the complexities of a large enterprise and is based on securing traction for a particular initiative among its multi-layered ranks. It centres on the principle that, aside from the usual delegation routes through the existing organizational hierarchy, there needs to be additional oversight from the person at the helm. They should be responsible for skippering their team on precisely what each member is required to do, to maintain control of the project.

In this way management needs to apply leadership to drive context down into the operating divisions and in one way it is an extension of the long-established practice of ‘Management By Walking About’ (MBWA) so it involves direct participation and a high level of familiarity with organizational practices and the enterprise’s employees, but with an additional dimension.

(Reproduced by kind permission of Caroline Waters.)

FIGURE 5.4: The Waters Model for Driving Organizational Change

The model in Figure 5.4 sets out a way of navigating the various silos which exist in a large organization:

• The pyramids describe a typical organization with a series of divisional silos;

• The gaps between each pyramid represent the vacuums between each division.

Each has its own characteristics informed by its function and purpose, as well as its custom and practice. They also have divisional systems – career, paths and processes. Underpinning these will be the people-related aspects such as culture, politics and egos.

Take, for example, the typical career journey of an individual employee in an organization. On joining, they will encounter the compelling experience of belonging to a department or a team. As they progress up the leadership ladder they will focus more on their own personal agenda and that of their particular area, which limits their scope to their specific professional ‘turf’ or silo. What motivation do they have in going beyond their field and familiarizing themselves with other aspects of their organization?

Very few managers encourage their people to take time out to look over the parapet and scan what is a rapidly changing external environment. Many would argue that organizations are joined up at the top by management committees and operational boards and this is the appropriate forum for broader views to be discussed. In reality, how much of this is actually acted on subsequently? There is value to be had from co-opting a wider range of people to look at issues. Given their relative position, they may have different perspectives, which might even lead to better solutions.

In this context, the role for business leaders is to take a fresh approach to the traditional ‘command and control’ model. In addition to the normal management structures of administrating day-to-day functions via operational boards, etc., the CEO must take personal and visible responsibility to drive context down into the vacuums between the divisions in providing a clear unequivocal and physical direction, which demonstrates a consistent journey by joining up the functions of the enterprise on a common roadmap.

By filling these inter-divisional vacuums, the CEO creates a genuine organizational ecosystem, which is much more resilient and self-supportive than the traditional hierarchical or matrix approach. It also gives out an unequivocal message to employees that this organization values their input and is worth working for.

Harness the Power of People and Place

The importance of connecting people and place has been explored earlier in Chapter 4, as well as how business leaders could profit from linking the two together for the benefit of their organization. This section extends the theme to include three further ingredients:

• Understanding the total operating costs of the people working in your organization, including the space they consume and the value they add;

• Recognizing that the workplace now operates differently;

• Applying the Workplace Management Framework to transform the workplace.

People-related Operating Costs

A great deal of time and effort has been expended on understanding occupancy costs in relation to leasing office space. They are usually articulated as cost per square metre or per square foot, yet I suspect that many business leaders are quite baffled as to what cost per square metre/foot actually entails.

As the world of work is changing and the idea of how the twenty-first-century workplace is evolving alongside it, the emphasis has to shift from being solely about office leasing and operating costs. Since a company’s greatest asset and expenditure is its staff, then perhaps it is time to factor people into the occupancy cost equation. So, what about using a system based on total operating cost per person rather than per square metre or square foot? Furthermore, the definition of ‘person’ would include the entire spectrum of people who work for the enterprise, including not only full-time employees but also remote workers.

This holistic approach was undertaken by BT to address the issue of the amount it was paying for its employee labour, together with what BT provided to its staff and the associated costs. This facilitated understanding the people costs of running the business; in parallel, it also enabled BT to start seeing how each sector added value to the business.

By applying this fresh perspective, the company was able to build a much broader concept of managing its people by turning BT into a porous organization. This is described as ‘one in which the boundaries are highly permeable across functional interest areas within the organization, as well as between the organization and the external environment’. A porous set-up can also be defined as one that evolves over time as circumstances change and the activities, demands and roles of those working there develop at different stages.

By figuring out the total ‘worth’ of their employees and developing a workforce management approach based on a porous organization mindset, BT took out approximately £1.5 billion of costs. Figure 5.5 is the result of BT’s journey into developing the People Related Occupancy Costs (PROC) System.

(Reproduced by kind permission of Caroline Waters.)

FIGURE 5.5: People Related Occupancy Costs (PROC)

In directing a fairly dramatic and drastic downsizing, BT had to be careful in considering how it would impact its people, most of whom had been lifelong employees who started off as civil servants since BT was originally a department of the UK’s public post office service. They enjoyed generous public sector pension packages, but more importantly, had amassed a tremendous pool of skills, experience and knowledge, in addition to being part of the organization’s history. Aside from providing generous severance payments, BT also wanted to find a way to retain their resources.

The PROC model has a core of in-house full-time personnel and the concentric circles emanating from the centre include freelancing/temporary workers, contractors, consultants, service providers, who are paid a fee for their work. This system provided a useful frame of reference and formed the premise of finding opportunities to move BT staff, especially long-standing experienced employees, to the outer rings. A key aspect was actively encouraging those wishing to leave BT to become entrepreneurs or ‘intrapreneurs’ and populate them into BT’s supply chain.

In many ways, PROC is a practical interpretation of Charles Handy’s Shamrock organization (see pp. 64–5). It recognizes that most enterprises now have a diverse range of ways of engaging with labour. The model defines the various components of the ‘new look’ workforce. The question is whether the total operating cost of each section is adequately captured and understood, especially the quantum of space the various categories consume. For the most part the add-on costs are reduced to just applying a percentage to core salary/payroll.

As one cannot look at real estate, technology, HR and other costs in isolation, applying this strategy might help to eliminate both inefficiency and fragmentation, plus improve the performance of a highly capital-intensive resource – an organization’s people. The benefits are two-fold for business leaders: in becoming informed clients they can drive for more sustainable construction and operational solutions, which would significantly impact their bottom line.

Applying the Workplace Management Framework

Who is best placed to deliver change in an organization can be a moot point. The received wisdom is that it usually falls to the HR division. While there are many methodologies and change models available to map out the journey and define what needs to be accomplished, I have seen little reference as to how to achieve change management involving a real estate move. I found the simple framework adopted by the International Facilities Management Association (IFMA) and Workplace Evolutionaries (WE) to be the best roadmap in understanding the various constituents involved when it comes to workplace transformation. This was formulated by Andrew Mawson and Dr Graham Jarvis of Advanced Workplace Associates (AWA) – see Figure 5.6, below.

Underlying this framework is AWA’s belief that effective change management is all about ‘preparing and supporting people to adopt new thinking, behaviours, practices, understandings and competences’. It also encompasses the physical, technological and social environment in which work is performed, which can be done anytime, anyplace and anywhere.

(Reproduced by kind permission of AWA.)

FIGURE 5.6: The Workplace Transition Management Framework

This framework comprises of ten management capabilities which determine how the organization achieves workplace change in the best possible way:

• Strategic Management is the core element which has to align all the assets and service management programmes to those of the organization’s business. It must engage with the C-Suite to interpret the demands of the enterprise and drive them down to the services;

• Client Relationship Management develops an understanding of the demand for the assets and services provided by the workplace through their relationship with the organization’s internal clients and its consumers;

• Performance Management measures the effectiveness of the operational delivery and quality implementation of improvement plans;

• Supply Change Management ensures that services are provided so that they support the strategic needs of the enterprise;

• Capacity Management provides services, technology and physical assets in the most economical way to benefit the organization;

• Resource Management – the day-to-day management of resources, encompassing the physical, utilities and employees, which ensures the effective running of the workplace;

• Improvement Management ensures that the workplace experience and the service performance is improved in a cost-effective way;

• Risk Management identifies and analyses the sources of risk which could impact employees and minimize the effectiveness of the workplace. Also, how malfunctions will be managed and how recovery from disasters is handled;

• Change Management endorses and supports the way the changing services/assets are used in the workplace;

• Project Management – primarily aimed at CRE/FM to plan, organize and put procedures into place to complete projects on time and on budget.

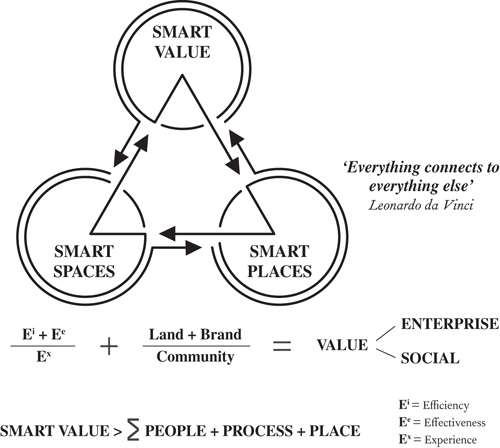

Apply Smart Value Navigation: The Background Behind Smart Value

In exploring new ways of helping the BBC to make the best use of its real estate while supporting its ambition to produce great broadcast content, it struck me that the relentless drive to cut occupancy costs was only part of the equation. It was through listening to the advice from the creative side of the Corporation such as the then Director of Drama and Entertainment, Alan Yentob, Peter Salmon who was the Director of BBC Studios, and the Controller of Operations, Sally Debonnair, that it became clear that it was also very much about creativity too.

This revelation led me to commission a piece of research into what makes a creative working environment. It was inspired by my collaboration with Philip Ross, a leading authority on new ways of working, and architect Clive Wilkinson – the designer of Chiat/Day Building in Los Angeles, known as the ‘Binoculars Building’ – who has been at the forefront of introducing alternative ways of using office spaces. Their ‘Creative Spaces’ advice helped steer my team to gain a much better appreciation of how other organizations across the globe view their places of work as enablers of creativity.

This was the springboard for Smart Value and the BBC’s workplace department used the concept in its most elementary form to roll out the Corporation’s new real estate strategy – ‘The Creative Workplace’. One based on massive consolidation and rationalization, which centred on driving down costs by being efficient and providing an effective, agile workplace which could enable great content production. Yet at the heart of this was the constant focus on supporting the BBC’s creativity. Additionally, the basic Smart Value framework was used to sell this large-scale estate transformation to win the hearts and minds of sceptical BBC divisional leaders. Plus, persuading nervous and apprehensive executives to come to terms with the overwhelming notion of the BBC’s moving out of London to other hubs around the country.

Given the huge amount of change taking place across the BBC’s portfolio throughout the UK and considering the BBC’s unique role in the fabric of the nation, I recommended to the board that we get some external strategic advice on an ongoing basis. This gave birth to a group with the unwieldy title of the BBC Architectural Design and Workplace Advisory Council (ADWAC), chaired by pioneering workplace strategist Frank Duffy. This high-profile creative group helped ensure that the masterplan for MediaCityUK in Salford and White City in West London worked for the BBC and for its other stakeholders.

Through the ADWAC discussions I framed my views on spaces and places, plus I saw the potential for the consumer to influence the direction of the master-plan design. After all, for the most part regeneration and development projects are mostly designed on what architects and developers perceive as being the best solution. This undoubtedly means both a certain degree of uncertainty and a great deal of risk as to the outcome of the scheme.

Solving the seemingly intractable problem of selling Television Centre in White City provoked me to take Smart Value thinking to the next level. Having been advised that the market would not pay much for the property in a run-down neighbourhood at the height of the financial crisis was bad enough. This was compounded by the BBC piling on added constraints, such as ensuring the legacy of the BBC’s historic television studios and maximizing its value, which spurred me to re-evaluate Smart Value.

The impetus for Smart Value was sparked by a ‘Eureka’ moment standing on the roof of the BBC’s Television Centre in 2008. From that vantage point I could see the potential of linking the BBC brand with that of its White City neighbour, the newly-opened Westfield London shopping mall, then one of the largest shopping complexes in the city. Additionally, in 2009, Imperial College, a world-renowned centre of scientific excellence, bought a former BBC vacant lot to house its new innovation hub. So, by allying three premier ‘brands’, value was added to the land, which attracted developers, investors and other leading companies to this once-neglected area. How Smart Value impacted on the evolution of White City will be discussed further in Part 2 – The BBC Story (see p. 175).

FIGURE 5.7: The Smart Value Formula

The model is not a formula in the traditional mathematical sense. It has been designed to be easily understood, since most people find numbers and figures simpler to digest. Essentially, it is a framework dressed up as an equation to help stakeholders appreciate a complex topic, albeit through a different more strategic lens. Put simply, it is all about joining the dots, reiterated by Leonardo da Vinci’s quote, ‘Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else’, which I find is true about most things in life. I was also influenced by another thought-provoking piece by da Vinci – his drawing of the Vitruvian Man, which is described as ‘seeing the world upside down and back to front… as a way to understand reality better’.

I have attempted to create a graphic depiction of how to take a realistic view in making the best use of the workplace. All stakeholders have a different perspective on the office, the Smart Value framework attempts to help everyone see the workplace in a holistic manner.

Smart Value has two interdependent components: Spaces and Places. Regardless on which side of the supply/demand one sits, spaces and places cannot be looked at in isolation anymore.

For Smart Spaces – this part of the model was informed by the two elements, Efficiency (Ei) and Effectiveness (Ee), and these are extended to include (the workplace) Experience – which comprises both wellbeing and engagement (Ex).

For Smart Places – this takes the perspective of the consumer, as opposed to the supply-side, urban planners, architects and developers.

In the case of an enterprise they would normally be concerned with the cost/value, the technical characteristics of the site or the piece of land they occupy. However, now they would also consider the impact their brand has on the location. This is not only about having a logo on the building, but incorporates the much wider field of brand appreciation, such as engagement with the surrounding neighbourhood and improving amenities for all.

Underpinning all of this is how the location fits in with the local community and the emerging importance of sustainability. The days of anonymous non-porous office campuses are coming to an end and it is no longer just a matter of paying the zoning fees or making contributions to a local event. Neighbours demand much greater engagement, especially as some of them may be customers of the organization or even part of the workforce. By partnering with a developer effectively, the true value can be created and it can be easier to demonstrate in a transparent manner.

Value – When it comes to assessing value, there can be tangible and intangible benefits for both Enterprise and Society.

Value for Enterprise – Bottom line is that such an approach must generate business value. Taking my experience at the BBC as a case in point, using the Smart Value approach to sell Television Centre produced over £200 million for the Corporation, which far exceeded the £90 million originally offered through the conventional route of a developer purchasing the former BBC site, as well as delivering a range of business benefits.

Social Value – In recent years the community aspect and social value agenda has widened owing to the challenges felt globally from environmental issues, traffic congestion and workers’ inability to access affordable housing. So, the Smart Value formula also considers the emerging importance of the social value aspect. As a spin-off, this also helps the supply side substantiate its contribution to the ESG performance criteria required by its investors.

Reach Safe Haven – A Great Place to Work

After making a sea crossing, seafarers breathe a sigh of relief when land is in sight, yet they recognize that the journey is not quite over. There is one more obstacle to navigate: getting into port and docking safely. Larger commercial vessels are usually aided by pilot tugs, but smaller boats use a pilot’s book or a set of charts to reach their intended berths. So like a skipper who is almost in sight of the journey’s end and has to manoeuvre into port, business leaders who are navigating the transformation of their workplace also need to be steered to reach the end product – in their case, a Great Place to Work!

Overall, a ‘Great Place to Work’ is one which enables people to work productively, where they are content with the purpose of the organization who employs them and makes them feel part of an organic community of workers. It also has to be one where there is minimal friction in getting work done.

Additionally, a first-class workplace should:

• actively support employees to carry out the job they have been hired to do;

• meet the diverse needs of the various roles people carry out at work;

• engender a sense of pride;

• help create a strong sense of community.

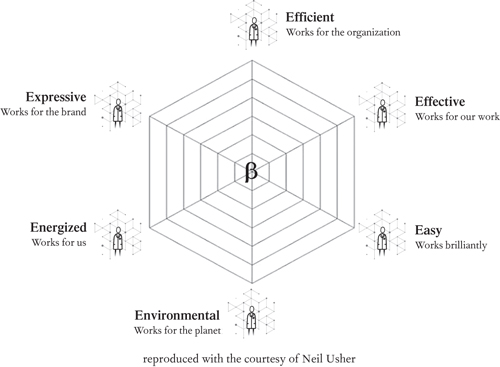

So, to help leaders create the vision of what they would like the twenty-first-century workplace to be for their particular organization and one that is suitable for the needs and demands of their business, I would refer them to the thinking of my friend and fellow traveller in workplace strategy Neil Usher, who has been behind many workplace change programmes all over the world for the past 25 years, as well as being the author of The Elemental Workplace.

This thought-provoking guide provides many tips to pilot executives into port in order to realize their ideal workplace – and it cannot be stressed enough that ‘one size’ does not fit all. Neil has also set out six ingredients to make the finished product a great place to work. These are set out in Figure 5.8 above, which has become known as ‘Neil’s Diamond’!

(Reproduced with kind permission of Neil Usher.)

FIGURE 5.8: Neil’s Diamond – The Six Es

The model is an extension of Frank Duffy’s original framework of the three Es – Efficiency, Effectiveness and Expression. They all add up to create a workplace which is conducive to the performance, productivity and wellbeing of the people who work there. In summary, here are some key points of Neil’s six-sided diamond:

• Efficiency (for the organization)

Reduces overall space required. Allows for flexibility of size within working teams. Enables learning and growth;

• Effectiveness (for work)

Brings out the best in people. Enables choice. Allows people to work their way, whether in a team or independently. Creates workplaces which inspire and motivate;

• Expression (for the brand)

Employees feel valued and appreciated. Promotes the attraction and retention of talent. Supports social responsibility;

• Environment (for the planet/society)

Fosters a caring culture. Cultivates a commitment to the local community. Engenders responsibility for sustainability. Creates awareness of energy resources/ethical issues;

• Energy (for people)

Supports employee wellbeing. Reduces absence and illness;

• Easy

A great workplace should just work brilliantly!

Discovering New Horizons

The impact of the various disruptive forces in the form of enabling technology and a host of new players coming into the very conservative real estate industry means that at the moment it is in a state of flux. The current status quo needs to be explored with an alternative approach looking at the two key dimensions of supply and demand.

Over the last 20 years there has been much discussion about the agile workplace, as well as flexible and agile working. These are examples of a range of generic labels which emerged to reconcile the range of choices people now have in terms of how they work. Initially, the option was a binary one – you either worked in the office or at home. The advance of technology saw the emergence of third spaces such as coffee shops and the like, made possible by the expansion of better connectivity, which opened up a whole host of alternatives as to where and when people work. This was coupled with the arrival of a herd of flexible space providers mixed in with the birth of ‘Workplace Strategy’ as a standalone advisory function, its purpose being to advise occupiers on the best use of space. So how have the providers of offices responded to this shift in demand?

The real estate sector is notoriously introspective as it has never really had to go out and seek customers – encapsulated by the business model of ‘build it and they will come’. As indicated, this is a sector whose approach is notoriously singular, siloed and self-centred. However, a hidden paradigm shift to a more people-centric workplace has reshaped how business can consume office space. Nowadays, from large multinationals such as Unilever to traditional SMEs and new start-ups, all focus on flexibility when it comes to offices.

To paint a picture of what this all means Figure 5.9 below demonstrates the emerging new pattern, where consumer demand will give rise to a significant re-balancing of the traditional offer, which was dominated by long-term leases or buying a freehold or taking a sublease. As indicated, the alternative flexible office market will explode to become much more significant. It is estimated to be 30 per cent although some commentators predict an even bigger percentage. This opens up a completely different range of possibilities for innovation and entrepreneurs – for example, what new products are there to run alongside the traditional leasing model?

FIGURE 5.9: The Evolution of Office Consumption in the Twenty-first Century

The growth of flexible solutions has now created a multiplicity of work settings for the ‘liquid workforce’. Each of the options where people can work, be it office, home, remotely or in a third space, has providers offering solutions. The other elements one has to consider are not ‘place-related’, such as working across time zones and engaging with work outside of the traditional days or hours of the working week and even work which is done via a job share arrangement.

This concept needed a label and the clichéd multi-dimensioned workplace did not quite fit the bill since it was anchored in the ‘place’ aspect and does not factor in ‘activity’. DEGW alumna Despina Katsikakis, now International Partner and Head of Occupier Business Performance at Cushman & Wakefield, pointed out, ‘We need to recognize demand is dynamic whilst buildings are static. The only way to reconcile the two is through embracing a dynamic portfolio flexibility and on-demand spaces.’

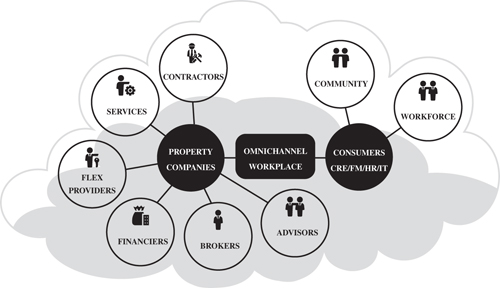

The Omnichannel Workplace

The inspiration behind integrating the multi-layered twenty-first-century workplace offerings came from former BBC colleague Dave Crocker, now CIO of US care-plan provider AllyAlign Health. He suggested that I look at what happened in the retail world with the emergence of omnichannel marketing. The concept being both traditional and digital channels are used in-store, online and at point-of-sale so a seamless, integrated and consistent customer experience is orchestrated across all platforms. This resonated with me as a way of explaining this paradigm shift to a twenty-first-century workplace based on providing and consuming offices across to a much-wider spectrum and creating an explosion of optionality in the context of an ecosystem.

Figure 5.10 below describes the new spectrum for consuming offices from fixed to fluid. It includes what are status quo options which will remain but are no longer the sole choice of the consumer. This is now recognized by a growing number of players on the supply side, as John Duckworth, MD of Instant Group, points out, ‘the real estate industry is at a crossroads, as it has been operating on a 150-year-old blueprint, which is now outdated.’

Whether or not the traditional gatekeeper role played by the broking community is sustainable is a moot point. Will it be threatened by disintermediation? Clearly there are plenty of new entrants to the market operating under the Proptech umbrella who are seeking a share of the lucrative broking commission pie. While transaction costs of this nature have always been the bane of the CRE leader’s life, conversely there is also growing discomfort among the property sector concerning broking fees. Certainly, this unease over vast fees should be a subject for concern for the leaders of the major property advisory and transaction houses.

The schematic in Figure 5.10 aims to demonstrate that it is now possible to take a more holistic view of the entire system for consuming space. There has been much comment on the flex-sector and all its component parts, but has anyone taken a 360-degree view of workplace offerings. According to organizational management specialist Fons Trompenaar (see also p. 106) we all have ‘a bipolar view of office work’ – one that involves either working in your own office or an open-plan to one that comprises working in an office building or at home.

The schematic describes a variety of working modes, more than ever before. While the Covid-19 crisis of 2020 focused attention on working from home, the truth is that it is now possible to consider a much wider permutation of options. Especially as managers are becoming more comfortable with the shift of large numbers of office staff working in different ways. The reason being that this shift actually runs on two parallel dimensions – not only where work is done, but when it gets done – and this defines the move from fixed to fluid. It is one which retains traditional core office structures, such as headquarters which will be leased, but can also be expanded to include the emergent range of flex sector options; including working from home, in cafés, on the move and in a plethora of flex-space options. I believe this emergent sector will become more significant, as was discussed in Chapter 3.

However as technology progresses it is also important to include virtual options into the mix. AI, avatars, chatbots and digital twins5 have come out of the realms of science-fiction and into the workplace, with many forward-thinking global companies already using these computer-generated devices for training purposes or to test out organizational structures, change management scenarios and the effects of ideas virtually, before implementing them for real. When it comes to defining space needs, the potential of these virtual tools working alongside people needs to be considered, as in the case for chatbots potentially replacing call-centres. These factors should be considered when businesses craft distributed workforce strategies.

All this indicates that the time has come to wake up to the opportunities presented by the shift from an analogue way of providing and consuming space to one based on the new reality of digitally enabled working, where the emerging wider range of choice offers consumers what they have been lacking for years. As part of this shift in thinking we need to consign the building-centric twentieth-century mindset to history and think about a more people-centric twenty-first-century ecosystem of work based on a distributed workforce approach and economically viable for all. Additionally, it also generates real social value and takes account of environmental factors.

FIGURE 5.10: Omnichannel Working – The Workplace Redefined

The Twenty-first-century Workplace Ecosystem

It never ceases to amaze me how the real estate industry functions, given its fragmented nature. However, there are ‘green shoots’ as we are on the verge of seeing the paradigm shift become reality. At this point it makes sense to consider how all the various stakeholders might adjust to the disruption to our existing analogue system.

Debating this with my Six Ideas business partner Max Luff, who specializes in systems thinking, we landed on the concept of thinking about the situation in terms of a twenty-first-century digital omnichannel ecosystem. This system advocates for a workplace which is dynamic, active and curated. One where all the existing stakeholders can either continue to operate as they have always done or they can explore new opportunities. The principal difference being that all parties are freed of the existing analogue constraints, where the transaction of space is the sole preserve of the broking community and transacted via a complex, costly and convoluted lease contract. Exploring this nascent omnichannel approach to support the multi-faceted demands of the twenty-first-century workplace, it makes sense to also consider the roles of the key stakeholders. Figure 5.11 below sets out the prototype of this new framework.

FIGURE 5.11: The Twenty-first-century Workplace Ecosystem

To harness the potential of having much greater choice there has to be a significant adjustment on the parts of both the demand and supply side of the old equation. It also involves reimagining the roles of the intermediaries and brokers.

The new look office supply model recognizes that the best results emerge from having the benefit of multiple inputs. A big idea and not one designed by committee, it also calls for a variety of involvement from across a wide spectrum of stakeholders. This is not an easy process and since it is not straightforward, it will require perseverance. First, it envisages a fluid and flexible system for the provision of offices which is underpinned by the concepts of a distributed workforce.

The New Look Supply Model

These are some of the potential characteristics of what the supply side might look like:

• The traditional leasing system would continue, but not as the dominant component of the market;

• Property owners could develop portfolio wide propositions for customers as an alternative/extension to the core long lease offer;

• There will be a focus on the whole life cycle of the building and not just on the construction phase. Providers will really have to get their heads around how the building enables people to work and the nature of that experience;

• User experience, wellbeing and sustainability matters will be seen as critical success factors;

• Design and construction providers get serious about modular and fully embrace BIM (Building Information Modelling) technology throughout the entire life cycle;

• Similarly, the property/asset management function will be digitized and will be more customer service orientated;

• Reward systems for all stakeholders need to be overhauled;

• There will be multiple new players and new offers in the advisory segment;

• The current raft of flexible providers will continue to expand and offer a more coherent value-for-money service based on true ‘plug-and-play’ offerings6;

• The FM model should expand to include not only the experience and wellbeing dimension, but the entire omnichannel working experience;

• The Proptech sector will provide a wide array of initiatives that facilitate the rapid roll out of change;

• All parties will need to consider the true impact of AI/avatars/bots/ digital twin technology in both how we work and how we support work.

A New Look Consumer Model

If the purpose of a workplace is to enable business performance, then this system considers the premise that business leaders review how their internal support functions enable work and productivity in the twenty-first century. Underpinning this thinking is the concept of redefining place according to the omnichannel model. This entails considering how their enterprise goes about delivering change, procuring assets, operating real estate, undertaking capital projects and delivering technology solutions. However, the following factors have to be considered:

• There is no single point of leadership in how an enterprise enables its staff to work in an efficient and effective manner;

• Technology is now a commodity and has effectively ‘left the building’ so the need for large help desks and IT support teams has diminished. Furthermore, ‘Bring Your Own Device’ is the order of the day for a large part of today’s workforce;

• The world of HR is rapidly automating;

• The schism between FM and CRE is inefficient and the two groups need to be fully integrated, including becoming better consumers (intelligent client) of the supply chain;

• Procurement in the main struggles to deal with anything complex, intangible and people orientated;

• The turf wars and the chasm of misunderstanding between all these groups reduces speed to market, focuses effort on non-strategic priorities and is not outcomes based.

Intermediaries

The current arrangement of the brokers as the single conduit between supply and demand changes to a multi-dimensioned one. The increasing developments in Proptech will only accelerate the disruption of the old order. For example, the leasing transaction procedure would be digitized, requiring the broking community to re-invent themselves.

In order to progress with the development of this prototype, there are six features which are necessary to foster the ‘green shoots’ of progress, enabling them to sprout into something worthwhile. This would make the model useful to all parties, as well as being economically and environmentally sustainable:

• Respond to the huge changes taking place in how we work and use offices, made possible by technology;

• Recognize that the system of providing, supplying and operating offices is undergoing dramatic change;

• Rapprochement between the principals involved in the supply and consumption of offices, creating a different type of customer-focused relationship and not one anchored by landlord and tenant mindsets;

• Reinvention of the intermediary (broker) to provide their clients with real value-added services fit for twenty-first-century purposes;

• Revisit the way corporations lead and manage their support functions and refocusing them on enabling work – reviewing how the traditional support functions of HR, IT, Procurement and Real Estate/FM can be unified with fresh leadership;.

• Reduce the environmental impact on our planet by using infrastructure and buildings in a smarter way, while building real engagement with the emerging ESG/Social Value agenda.

Reap the Rewards

Together with the frameworks and guides in this chapter provided by those who have piloted successful workplace transformation projects, I hope that business leaders will have a better understanding of how to navigate change by harnessing their workplace to better advantage, whether the journey is one that makes better use of existing offices or one that requires moving to a new facility and using it as a catalyst for organizational change. Of course it is up to the leaders of organizations to use the suggested guidelines or even opt for a ‘pick and mix’ approach depending on their needs and goals, as well as those of their particular enterprise. I hope at the very least that the ideas and guidance offered will be ‘food for thought’ and might encourage people to view the workplace through a different lens. Even if that just means positioning yourself in the shoes of other stakeholders, which might alter long-held precepts and processes.

One common thread underpinning my thinking is the need for an improved relationship between customer and supplier. Building stronger links opens a wider range of possibilities. More importantly, each group just needs to see that by taking a different approach, they can harness wider value and greater benefits.

In the case of business leaders, the advantages could be as follows:

• A much easier and more transparent decision-making process;

• A variety of improvements to the underlying performance of the business based on:

○ superior competitive advantage;

○ faster speed to market;

○ brand awareness and standing;

○ better employee engagement;

○ improved staff attraction and retention;

○ demonstrable contribution to the sustainability agenda and carbon footprint reduction;

• By having a better understanding of the associated enterprise and project risk profiles leaders can make better informed decisions on how to mitigate exposure.

There are also positive gains to be made by the supply side, whether they are providers of buildings or services, as UK developer and REIT The Peel Group has discovered. As one of the creators of MediaCityUK, Executive Director Stephen Wild views placemaking and stakeholder engagement as equally important to the company’s success as its finance and management departments so by closing the emotional connection between tenant and landlord, the supply-side could:

• reduce voids;

• increase returns owing to better-informed client needs;

• create an opportunity to streamline/automate the process;

• improve levels of customer relationships, leading to more repeat business.

One of the most overlooked or misrepresented stakeholders in a business yet one of the most important is the actual workforce. Henry Ford recognized their value when he said: ‘You can take my factories, burn up my buildings, but give me my people and I’ll build the business right back again.’ The average office worker can derive many benefits from having an enlightened management apply principles, such as:

• better working conditions;

• encouraging their employees’ sense of self-worth;

• improving staff engagement with the business.

Finally, organizations have to consider the wider community and society as a whole. Professor Franklin Becker, Director of the International Workplace Studies Programme at Cornell University, asserts that there has to be a more ‘joined-up approach’ and ‘a shift of focus from the “built environment” to a “community ecosystem” way of thinking’. At present this is at a very rudimentary stage, but these factors could deliver the following benefits:

• better engagement between the corporate office and the local community;

• opening up opportunities for collaboration through connections with local people;

• creating better amenities, which serve both the workforce and the neighbouring community.

All in all, it is difficult to see why employing some or all of these ideas would not yield positive outcomes. They are not all that radical but could help savvy management to navigate their enterprise successfully through the storms of the VUCA world into calmer waters. English Historian Edward Gibbon wrote ‘the winds and waves are always on the side of the ablest navigators’ – as long as leaders understand how to steer their organization to a safe harbour.

Sources

1. ‘We cannot direct the wind but we can adjust the sails.’ Bertha Calloway.

Clark Hine, D. & Thompson, K. A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women in America. New York: Broadway Books, 1998, p.240.

2. ‘one in which the boundaries are highly permeable across functional interest areas within the organization, as well as between the organization and the external environment’.

Bartone, T. & Wells II, L. ‘Understanding and leading porous network organizations: An analysis based on the 7-S model’, Center for Technology and National Security Policy National Defense University, 2009, p.1.

3. ‘preparing and supporting people to adopt new thinking, behaviours, practices, understandings and competences’.

Keller, S. & Aiken, C. ‘The inconvenient truth about change management’. McKinsey & Co., (2008), p.3.

4. ‘You can take my factories, burn up my buildings, but give me my people and I’ll build the business right back again’. Henry Ford.

Boone, L.E & Kurtz, D.L. Management. New York: Random House, 1987, p. 138.

5. ‘The winds and waves are always on the side of the ablest navigators’.

Gibbon, E. The History of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: J.F. Dove (1825). Vol. VIII, Chapter LXVIII, p. 235. (1787)

Epigraph

Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity. London: Geoffrey Bles/Macmillan Group, 1952.

© copyright C.S. Lewis Pte Ltd., 1942, 1943, 1944, 1952. Used with permission.

Notes

4 McKinsey Survey. ‘What successful transformations share’, McKinsey & Co., 2010. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/what-successful-transformations-share-mckinsey-global-survey-results

5 Avatars – virtual workplace aliases. Chatbots – computer programs designed to communicate with people virtually. Digital twins – a virtual copy of a living or non-living physical entity.

6 A alternative take on the original technology-based view of Plug-and-Play which describes computer equipment, for example, a printer which is ready to use immediately when it is connected to a computer. So a Plug-and-Play workspace is one which is available on demand, rather than having to negotiate a lease, prepare the space, add furniture etc.