‘Oh my God! What have I let myself in for?’ I thought to myself, as I looked around the room at the faces of various BBC executives and the then CEO or Director-General Greg Dyke congratulating me gregariously and welcoming me warmly as Director of Property/Head of Corporate Real Estate of this iconic British institution. This was back in January 2004 and I had swapped the roving life of Disney’s Magic Kingdom for a once-in-a-lifetime chance to lead the world’s oldest national broadcaster and one of the UK’s most globally recognized brands in a £2 billion property expansion programme.

I could not help but be struck by the history and the cultural significance of the place as I wandered the warren of hallways and radio recording studios at the BBC’s distinctive 1930s Art-Deco Broadcasting House in central London. Or around the maze of studios in Television Centre in Shepherd’s Bush, West London with its unique circular question mark design, affectionately referred to as ‘the doughnut’ by BBC staff. The entire spirit and history of a nation’s life seemed to echo from its walls: it was remarkable to think that George V, the present Queen’s grandfather, first broadcast his Christmas address (scripted by Rudyard Kipling no less) through the BBC in 1932. As Queen Victoria’s grandson he was effectively a direct link to the nineteenth century. During the war years the BBC transmitted Winston Churchill’s rousing speeches which became integral in boosting the nation’s morale during its darkest hours.

The new Elizabethan Age heralded the golden age of BBC TV as 3.2 million television sets were purchased in 1953 alone to watch a young Princess Elizabeth crowned Queen in flickering black and white; 15 years later, some equally grainy images were broadcast from a Space-Age designed Television Centre studio of ‘one man’s small step’ on the moon, witnessed by 22 million in the British Isles. These images brought to us courtesy of the BBC were certainly an awe-inspiring and memorable moment for me as a young lad.

Growing up, the BBC provided the narrative of our lives, with much-loved children’s programmes like Blue Peter, which is still going strong, featuring the nation’s cherished pets along with friendly presenters who encouraged us to make models out of everyday items, went on daring adventures and fostered our involvement in numerous charity appeals. Whole generations have memories of cowering behind the sofa on a Saturday afternoon as terrifying Daleks threatened to exterminate the world in Doctor Who. Our teenage years were marked by the weekly rave of Top of the Pops, Led Zeppelin’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’ riffs backing those all-important Top 10 charts. The BBC, both radio and TV, were integral to the success of British pop legends like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Queen, David Bowie and numerous other great bands and singers. Indeed, that global fame was harnessed for good when the world rocked together to raise money for famine relief in Africa – 1.9 billion people – 40 per cent of the world’s population – watched Live Aid that day in 1985 – all triggered by a BBC news report on the catastrophic tragedy of the Ethiopian famine, which galvanized rock star Bob Geldof to act.

In fact, it is astonishing just thinking about the amount of talent launched by the BBC in terms of well-known entertainers, actors/actresses, presenters, writers, producers, directors in addition to their first-class, innovative dramas, comedies, factual programmes, news services and documentaries, which are viewed internationally and have become popular globally. Even now, with so much competition in broadcasting, we are still inspired and educated by BBC programmes like David Attenborough’s groundbreaking documentaries on our planet and the natural world.

Another significant cultural aspect is the BBC World Service, which is still the world’s largest international broadcaster, transmitting in more than 42 languages. The BBC’s ‘London calling’ was a lifeline for occupied Europe and the Far East during World War II, with a certain George Orwell broadcasting on the Eastern Service. It was also a vital link to the West for those living under the Soviet-controlled Iron Curtain during the Cold War. Now, the rebranded World Service English and BBC World News reach 426 million international viewers per week, with an average of 38 million in the US.

Indeed, for many the BBC is a symbol of ‘Britishness’ and is woven into the psyche of the nation as ‘Auntie Beeb’; additionally, another unique feature which distinguishes this broadcaster is that it is funded by the British public through an annual licence fee. It certainly plays a big part in the organization’s decision-making and personally, I was very conscious of this during my time there. The fee is set by the British government and is classified as a tax; it also keeps the BBC free of advertising although commercial divisions have been added recently, which generate income through overseas sales of programmes and other profit-making ventures, which are returned back to its core production activities.

The other quaint factor is that the BBC is run by a Royal Charter, which outlines its constitution and sets out the public purposes of the Corporation while guaranteeing its independence. This agreement – presented by Royal Command to Parliament – is renewed every decade and inevitably when reviewed questions always arise over the increasing cost and validity of the BBC licence fee. Especially now in the age of digital TV with new competing networks offering their own subscription services. Another contentious point is the Corporation’s impartiality in its programming, which forms a big part of the BBC’s remit and is seen as fundamental to its principal values and maintaining the trust of its viewers. Nonetheless, this set-up means that the British public are truly invested in their national broadcaster, both financially and conceptually, and understandably they can get very vehement and opinionated at the way things are run at the BBC. It certainly attracts a fair amount of criticism from all quarters and depending on your outlook, it can be perceived to be too liberal, left-wing, politically correct, London-centric or right-wing, elitist, middle-class and a government mouthpiece.

Also, the question of the BBC’s public funding often causes controversy; whether the cost of productions, staff salaries or any expenses pertaining to organizational policies, with accusations of wasting licence payers’ money in ‘out-of-touch’ decisions – something I had to contend with quite often with our so-called ‘pie in the sky’ property strategies, which were viewed as profligate and unnecessary at the time.

Wallowing in BBC history and its past achievements, as well as reaping the rewards of the 2001 BBC/Land Securities Trillium Property Partnership, defined my initial ‘honeymoon’ period at the BBC. The real estate department had received great accolades, winning industry awards left, right and centre for this groundbreaking deal although I do recall that some of my peers remarked to me at the time that I was going to a ‘non-job’ since everything had been outsourced to Land Securities Trillium and there would not be that much for me to do!

Nonetheless, even back then in early 2004, a little over two years into the partnership, BBC Property seemed to be a bit like a swan streaming along, looking serene on the surface and furiously paddling underneath on a ‘wing and a prayer’ of substandard and outdated premises dotted all over the country. The estate’s portfolio was woefully underfunded and certainly not fit for purpose for twentieth-century standards, let alone the demands of the twenty-first-century digital age. Working conditions were so shoddy in places, to the extent that female colleagues at BBC Radio Leicester had to leave their office on the 12th floor of an old building and go to the adjoining shopping centre to use the WC.

When I joined there were three major new buildings in the pipeline, with one almost ready to move into: a new 500,000 square foot complex, curiously titled Media Village in White City, near the ‘doughnut’ Television Centre in Shepherd’s Bush. In the meantime, across in Central London the iconic Broadcasting House was in the somewhat painful throes of being rebuilt and in the regions a new lease had been taken on a spanking new space in downtown Birmingham, known as The Mailbox. The only element which remained constant throughout all this ‘root and branch’ transformation of the BBC’s property was that broadcasting had to carry on, no matter what!

Personally, I landed to earth with a thud a month into what seemed to be both a plum job and a challenging one, attempting to makeover Auntie Beeb into a modern, fitter, leaner broadcasting machine. Enabling her to take on the cable and satellite disruptors like CNN, Discovery and Sky, whose broadcasting tentacles were spreading globally and ready to face the onset of digital and subscription TV. Nonetheless Auntie’s cosy image took a real battering as a result of the Hutton Inquiry7 of 2003, which questioned the BBC’s impartiality and led to the sudden resignations of both its Chairman Gavyn Davies and the Director-General Greg Dyke, within 48 hours of each other.

Effectively for six months the BBC was a rudderless organization in turmoil, while undergoing one of the most complex and complicated transitions in its 77-year history. I needed to adapt quickly to a role which I had to make my own in being part of a tightly knit executive team headed by the BBC’s Chief Finance Officer, John Smith. It gave me some great insights into how events can come out of the blue and severely dent the confidence, morale and consequently the reputation of an organization.

The appointment of a former BBC2 Controller – Mark Thompson as Director-General – was perceived as a steadying influence after the resulting fallout of the Hutton Inquiry. Mark quickly grasped the potential in harnessing the regeneration of the BBC’s property portfolio as a means to facilitate or act as the catalyst for his organizational change agenda. He saw it as a much- needed ‘creative response to the amazing, bewildering, exciting and inspiring changes in both technology and expectations’.

BBC Property’s State of Play

I did feel that I was on the cusp of doing something radical for the BBC in 2004, in terms of introducing new ways of working and how real estate could make its contribution in transforming this extraordinary organization. Obviously, a project of this magnitude required a good team of people who were all ‘singing from the same song-sheet’. However, what I had inherited was a fragmented and disjointed in-house property function, who certainly did not have the capability to deal with the tsunami of work it was expected to deliver.

BBC Property had recently merged to bring together the traditional asset side and facility management teams under one roof. It was evident at the time that these two groups were uncomfortable with each other – in fact, they were like chalk and cheese. FM were trying hard to deliver a great customer service, while Real Estate’s function was deeply rooted in its traditional view that they were the BBC’s in-house landlords. Delving deeper into BBC Property, I discovered a culture of inadequate decision-making, limited accountability, poor levels of capability and a ‘master/slave’ approach to working with the supply chain. Despite these drawbacks, I also found plenty of capable people and team players, who just needed a bit of clear direction and leadership support to harness their potential so that they could take on the mammoth challenge facing them.

The whole department needed a complete overhaul and I needed a solid framework to help me map out how we might go about achieving the stated aims – the primary focus being helping the BBC move into the digital era, the other one being turning BBC Property into a strategic function within the organization. In the process I had to change my own organization totalling 2,200 people of in-house and service provider partners by going through a series of organizational changes to match our strategic journey. Thankfully, I received strong sponsorship from my boss, CFO John Smith and looking back it set the foundations for my views on organizational development and change – especially in evolving how to align property or the CRE function to the goals of the enterprise it serves. More importantly, as a property man, so to speak, the BBC’s organizational change taught me about people and how to lead teams across boundaries, cultures and processes that perhaps they would not otherwise have attempted to cross.

The Learning Curve

Despite the challenging circumstances facing me, I viewed my time at the BBC as a tremendous learning opportunity. Not only did I get to use the strategic analysis and leadership skills I had learned from my MBA, but I also got the chance to experiment and test a framework developed by my American friends, workplace specialists Professor Frank Becker from Cornell University and MIT’s Professor Mike Joroff.

Both Frank and Mike proposed that CRE professionals in any organization can move up the value chain from being mere ‘order takers’ to trusted strategic advisers. However, they will need to get to grips with understanding finance, technology, managing talent/people, planning, integration and other skills beyond real estate to add real business value to the enterprise they serve. This guidance was invaluable to me as a leader setting up the strategic direction for our group to help the BBC switch from analogue to digital. Being my own ‘boss’ so to speak as Director of Property certainly helped since the BBC treated its real estate division as a separate company, complete with its own finance director, the very capable Gerry Murphy. So, in this capacity it was up to me to ‘write’ the CRE rule book, my principal guidelines being:

• It is essential to align with the business;

• In delivering ‘best in class’ CRE/FM services, one has to operate as an ‘Intelligent Client’ – meaning there has to be commercial awareness and capability to effectively harness an outsourced supply chain;

• To achieve organizational change, it is vital to secure C-Suite support and sponsorship;

• Leverage existing tools and as many resources available to be used, as there is no point in reinventing the wheel;

• Another truism is to invest in one’s team as nothing can be achieved without their commitment and engagement. Personally, I found the ‘High Performing Team’ framework8 of great value. I used this to help the team to focus on their goals through sharing a common vision.

Navigating the BBC’s Ocean of Uncertainty

Looking around the BBC at the beginning of my ten-year roller-coaster journey, it was evident that many people regarded it as a very stuffy, civil-service driven organization and steering it successfully to a modern, twenty-first-century technology-enabled, flexible open-plan inevitably required perseverance and persistence. Undoubtedly, it could not have been done without a colossal team effort, made possible by the contributions of numerous fellow travellers in every area of the organization. We certainly had an enormous amount of novel and challenging work, which was fairly problematic, coupled with a suspicious set of BBC Governors (supervisory board), an executive team in transition, plus a non-existent relationship with our customers – the wider BBC who used our buildings and facilities.

Additionally, there were two goals to achieve: the primary focus being switching analogue Auntie Beeb over to digital broadcasting by 2012. Mark Thompson’s arrival as Director-General in 2004 really accelerated the BBC’s shift to digital and at that time, little was known about its implication, especially in terms of how audiences would react.

Mark talked a lot about ‘Martini media’ and the move to ‘an on-demand world’ – it was difficult enough for me coming from Disney and as a ‘newbie’ to come to terms with all this. I can only imagine what it must have been like for those BBC veterans who had been around for some time. Watching from the sidelines as broadcasting and production colleagues got to grips with some traumatic shifts in how things have been done across the BBC since 1922, three things stood out for me:

• Seeing how digital exploded, providing audiences with such enormous and varied range in programming after decades of the old analogue world of two TV channels and four radio stations. Now it is hard to imagine that today’s choice of 70-plus Freeview TV channels, plus more than 30 radio stations in the UK and over 200 channels across the US’s digital network, were but a gleam in our eyes about 15 years ago;

• Conversely, the big concern then was how would these rapid changes impact BBC audiences and how would they navigate this new digital world;

• Witnessing the birth of ‘citizen journalism’ and the impact of social media on broadcasting. This happened as a result of the July 2005 London terrorist attacks. These atrocities marked a turning point in how the BBC covered news. At the time hard-pressed colleagues in the newsroom talked of the tidal wave of hundreds of emails and texts arriving at Television Centre, along with hundreds of photos and videos pouring in from the public and the way they used this influx of information.

The other goal, which was my responsibility as Head of BBC Corporate Real Estate, was dealing with 500 buildings spanning approximately 7.5 million square feet, spread around the UK, most of which were in fairly bad shape. The property portfolio had suffered from over 30 years of underinvestment.

Most of the buildings could not physically accommodate the additional requirements of transitioning to digital broadcasting operations – even the basics, such as having the capacity for extra cabling. This was not surprising given that in 2000, less than 2 per cent of the entire portfolio of more than 500 properties was under 15 years old. To add to the problems, key leases were due to expire on some of the BBC’s larger buildings in central London.

The combination of all these factors was the impetus for the 1998 announcement of the ‘BBC 2020’ property vision. This aimed not only to address significant shortcomings in the estate, but to prepare the BBC for a period of tumultuous change, driven by new technology, increased competition and budget constraints. Nevertheless, through this major estate upgrade the BBC recognized it was essential to ‘open itself up’ to its audiences and stakeholders, increasing the imperative of securing new ‘fit for purpose’ buildings as soon as possible.

It was the far-sighted leadership of financial director John Smith at the time and his aspiration for ‘decent quality architecture across the whole estate’, which set up the framework for the Corporation’s property vision. John’s thinking was greatly influenced by his visits to open-plan environments in California, where he saw the cultural benefits they could bring to the workplace. He acted in conjunction with creatives Alan Yentob, then Director of Drama, Entertainment and Children’s BBC, and Tony Hall, who was Director of BBC News and eventually became Director-General. They also supported John’s appreciation for stimulating working environments in well-designed, functional buildings.

As part of this initiative they engaged the services of DEGW in the form of its founder Frank Duffy and then Head of Consulting/Chairperson Despina Katsikakis. They were tasked to take the first tentative steps in moving the BBC to open-plan workspaces, which was to be a physical signal of the Corporation’s desire to open up as an organization. Back in the late 1990s this was revolutionary for the BBC as it set up a test floor in Broadcasting House, where John took himself out of his Director’s office to sit at a team table. It was a far cry from the isolated offices/cubbyholes at the end of labyrinthine corridors occupied by the rest of the BBC.

This inspired test case in Broadcasting House led to the framing of the five key themes underpinning the 2020 vision:

1 Flexibility: Property must not restrict the BBC’s freedom to evolve its operations.

2 Technology: All BBC space must support future technological requirements without incurring costly reconstruction.

3 Talent: BBC buildings must be showcase sites of technology and innovation in order to attract and retain the best talent.

4 Audience: New competition would test public sympathy on the cost of the licence fee, so the BBC must demonstrate value by engaging local communities with opportunities to experience the BBC in action through live broadcasts and open access to buildings.

5 Cost: BBC Property’s role is to help the Corporation save money rather than spend it.

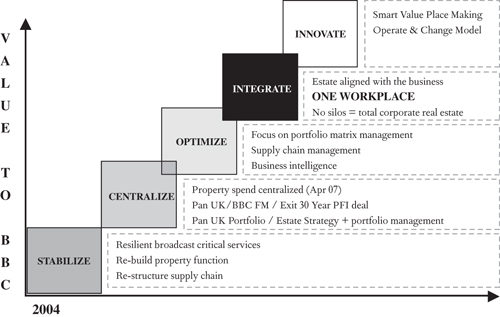

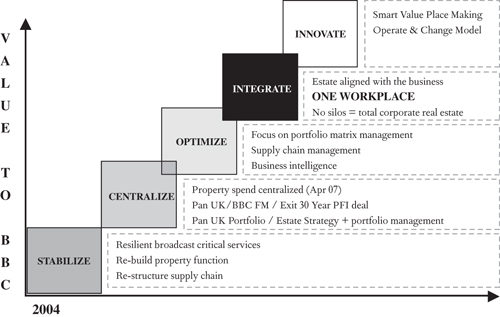

To achieve these aims I relied heavily on the framework provided by my friends, workplace specialists Professors Frank Becker and Mike Joroff at the then International Development Research Council (IDRC), the precursor to CoreNet Global. Their five-step process gave me the inspiration to look at the real estate/FM function and adapt it to incorporate the BBC’s property vision, see Figure 8.1. In this way everyone could visualize how the process of transition could add value to the BBC and how the CRE department could move from ‘order taker’ to a much more strategic role.

FIGURE 8.1: Framework for BBC Property 2004–12

In addition, it was also imperative that old-fashioned organizational silos must be broken down and different professionals had to learn to think and work out of their particular specialist boxes. I also realized that most workplace projects of this scale and magnitude fail because they focus on driving property efficiency at the expense of encouraging people effectiveness – driving down cost had to become an important, yet secondary factor. The key to success is creating a workspace that enables people to be more creative and productive. If that can be achieved, cost reduction and value generation will naturally follow.

Shifting the Focus to a Creative Workplace

Taking on all of this additional responsibility and learning by experience, plus dealing with all the ongoing project challenges, the property and facilities team I inherited in 2004 had been swept away in a tidal wave of intense activity. The group not only had to cope with enormous transformation on a massive scale over a few short years and in rapid succession, they also had to shift gears from dealing with run-of-the-mill estate activities to cope with a vast array of new construction projects all being developed concurrently: Central London’s W1 Broadcasting House, BBC Norwich, Birmingham’s Mailbox and the new campus at London’s W12 White City. The latter project was managed by the BBC’s Major Developments team under the very capable leadership of Tony Wilson. So, I decided we needed to reinvent the property, facilities and construction team by turning it into a more ‘business-like’ and coherent team and re-named it BBC Workplace.

Having kicked off a major team transformation within the old BBC real estate division, for me it reinforced that the property function itself would really have to step up to the plate and become much more strategic in its approach. This required some reimagining of the scope and reach of its role within the organization to enable the new look BBC Workplace to act as a trusted advisor to the Corporation, while collaborating more effectively in cross-functional teams, with both internal and external partners. In doing so, BBC Workplace adopted a mission whose stated aim was to ‘deliver the right workplace for the most creative organization in the world’. This all had to be accomplished with an eye to public value which required us, as property facilities and construction professionals, to really broaden our understanding of what this meant. To give it a business or corporate definition, it is a public-sector version of shareholder value. For me personally and all those in real estate, public value is an unfamiliar term, but it enabled us to see another perspective: that it was not just about rents per square foot or building values.

Aside from these factors, however, there was one serious obstacle remaining in our mission and that was demonstrating to the BBC Executive how real estate could positively contribute to the BBC change agenda by taking advantage of the slew of new spaces coming on stream, which could act as catalysts for transformation.

Crucially, Director-General Mark Thompson could see that regenerating the property portfolio could help facilitate organizational change so he stepped into the breach in September 2006 by calling all senior management involved to a meeting at Broadcasting House in London and tasked them to push the boundaries and take the risk in supporting our initiative. It proved to be a seminal moment, both for the rebranded real estate team, BBC Workplace and for me personally; looking back, it ensured these projects were delivered successfully.

BBC Workplace worked hard to define its contribution to the Creative Future business plan. We created a schematic to demonstrate how we would go about producing a truly creative workplace based on agile working, see figure 8.2. Our manifesto was to deliver business and public value in partnership with HR and IT at minimum cost and at maximum effectiveness. The proposal went down well because for the first time the BBC executives, embattled by constant and unrelenting demands for cost-cutting and efficiency, could now see an alternative, one which focused on matters closer to their hearts – creativity and collaboration.

FIGURE 8.2: Delivering Business Value through Agile Working

Undoubtedly it was difficult building bridges of understanding between the BBC’s HR group (people), its IT department and BBC Workplace. It required an enormous amount of effort to build trust between all the teams and get them on board with our common aims for the BBC’s new-look working environment. Shifting the focus was also not easy as the creative world, like many other industries, is full of egos and idiosyncrasies. A pragmatic approach was required, especially in attempting to roll out agile or alternative workplace strategies as part of the new generation of facilities. However, I did learn an important lesson: even if you provide a great new workplace, it is very difficult to harness the hearts and minds dividend if you try to introduce desk sharing in an existing space!

Another useful and new exercise BBC Workplace employed was to use Customer Relationship Management tools to engage with our stakeholders and also to demonstrate to external auditors, the BBC Executive, Governors and others how things were developing on the property and workplace front. A by-product of such was the publication of an annual report called the ‘State of the Estate’ – a comprehensive analysis of how the BBC used its real estate portfolio and how it benchmarked against the outside world. It was useful to have evidence such as this to contribute to the regular assessments of the BBC by the National Audit Office (NAO), the UK’s public spending auditor and watchdog.

The 2013/14 NAO report which came out in 2015 – a year after I had left the BBC and 11 years after I had taken over as its Head of Property – stated that it was ‘generally supportive’ of the BBC’s estate management and that it found despite large initial costs ‘the organization had made good progress in rationalising (by almost a third) and upgrading its estate. It had also improved its use of available space’. This was a great affirmation for BBC Workplace and its many years of trials, tears and tribulations.

Stabilizing the Good Ship BBC

It certainly helped me that the BBC had already started its major estate upgrade when I joined in 2004 and more importantly, it had charted its course with the ‘BBC 2020’ property vision. What was lacking was a clearly defined roadmap and delivery strategy and my job during 2004–06 was to figure this out and craft a plan which took the following parameters into account:

• Maximize space utilization to drive reduction in BBC costs and footprint;

• Leverage partnerships or other major occupiers, local communities, the supply chain and others;

• Ensure flexibility in order that the property portfolio could meet the needs of the business;

• Drive cultural transformation.

A pretty tall order! I recall visiting the BBC’s then Chairman, Lord Grade – now Baron Grade of Yarmouth – at his Marylebone High Street office off London’s West End to explain how we intended to get the BBC’s property ship back on course. Michael Grade has British popular entertainment and TV coursing through his veins, having served as Controller and Chairman of the BBC, as well as CEO of the UK’s main independent broadcasters ITV and Channel 4.

Being a highly experienced career-long broadcaster, Lord Grade hammered home to me the importance of getting under the skin of broadcasters and creatives if I was to make any headway with steering the BBC vessel on course. It was a great tip and reinforced what I had learned at Disney: it is all about the show, not the building! In short, it was the ‘missing link’ aligning the business with its real estate, which left me in no doubt that I had to drive an intelligent real estate strategy that enabled the BBC to deliver high-quality original content, inspire innovation, support new technologies and engage a global audience.

Taking Care of BBC Business

Lord Grade’s advice about really understanding the ‘business’ of the BBC was a message reiterated by Caroline Thomson, the newly-created Chief Operating Officer and my new boss from 2006, during her weekly senior team meetings. She religiously hosted these meetings at 8.45 a.m. every Monday, gathering the heads of all the BBC’s support and strategic units together, where we discussed any hot topics and set priorities for the week ahead. In this way, I found myself right in the epicentre of how the BBC functioned and it gave me enormous insight into the workings of a complex and highly politicized organization. Especially as it was going through some testing times following the announcement in 2005 that London had won the race to host the Olympics in 2012 – the same year the major switchover to digital technology was due to take place, as well as the BBC’s migration across to the renovated New Broadcasting House and up north to Salford.

To really get into the underbelly of understanding this multi- layered and multi-faceted national institution, I certainly wanted to try and do something different. One way was giving everyone in my team of over 2,000 people across all the BBC regions and at every level the opportunity to get involved and have a say in how we as a team could support the Creative Future initiative.

Bearing in mind that one criticism of the BBC was that it was too London-centric, rather than having one big ‘impersonal’ meeting in London, a member of BBC Workplace would hold a series of sessions and debates in London (in the main Central London W1 and West London W12 sites), Glasgow, Birmingham and Manchester. This certainly proved a valuable exercise because the comments made by my colleagues provided a pretty fair insight of how the wider BBC – a 25,000-strong workforce – felt about their working environment, their requirements and demands. To this end the Workplace Management team narrowed the points made to three main priorities which needed to be tackled first:

• Improve up and down communications: To find ways to improve communication across ONE Workplace team in all locations and reduce London-centricity;

• Simplify processes: To identify ways to improve the processes for initiating and managing jobs and projects;

• Focus on how to make the big picture small: To improve awareness of strategy at ground level, so staff know what is expected of them and how wider workplace aims are relevant to them in their everyday work.

The other key factor for me was that we ensured that everyone at BBC Workplace and the external supply chain understood ‘the show must go on’ and had to be kept on air – a challenge given the legacy of the old ‘master/slave’ mindset. Good progress was only achieved on this agenda as the leaders of our principal partner – Johnson Controls – responsible for FM grasped the importance of workplace services aligning themselves to the business of the enterprise. I was extremely grateful for the broad-minded attitude of Vice-President and General Manager at the time, Rick Bertasi, who was followed by Steve Quick, currently CEO of Cushman &Wakefield.

It was essential to the success factor for the new-look BBC Workplace team that it not only understood the business of broadcasting, but also spoke its language in conjunction with listening to the needs and requirements of the organization’s workforce. To build on our ‘One Team’ game plan we leveraged the BBC’s annual fundraising telethon Children in Need as a team-building initiative. Taking over the Children in Need studio the night before the main event allowed the entire team to put ‘its money where its mouth was’ in order to generate hundreds of thousands of pounds for this charitable appeal. All of this resonated with creative and operational colleagues across the broadcasting world and showed them that the property/workplace division was on their side.

The most important piece of advice, however, came from Tim Cavanagh, then Director of Workplace Operations: ‘stay on air and don’t kill anyone!’ To this day, I still marvel at how the BBC achieved putting out high-quality content to a global audience on a 24/7 basis with hardly a glitch despite all the troubles and turmoil involved during its decade-long transformation. In fact, during the six-year period of construction work on Central London’s Broadcasting House only eight minutes of broadcast outages were recorded. Hiring Dave Ronchetti, whose experience in overseeing the relocation of the UK’s air traffic control facilities, proved a wise decision. Especially since I discovered that six months before I joined the BBC, there had been major power problems at Television Centre, causing a series of unprecedented blackouts, when either television went dark or radio went silent. The most significant being the inexplicable loss of 20 minutes from the Today programme, BBC Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show, which has been transmitted live from 1957 – all the more embarrassing as during that time Tessa Jowell, the then Minister for Culture, who is also responsible for broadcasting, was being interviewed!

According to BBC folklore such an event is not merely an inconvenience to audiences, it has an even more sinister implication to do with Britain’s nuclear deterrent. A submarine commander, serving on one of the four Trident nuclear submarines, which for the most part are submerged, goes through certain protocols to determine if the UK continues to function. One of them is to check whether the BBC’s daily Today programme is still broadcasting – it would be interesting to note what the commander thought was going on when it went quiet that day in November 2003!

It was inevitable that something had to be done about Television Centre as broadcasters were tearing their hair out and demanding solutions fast. This also provided me with another key learning point: leaders need to step in and sort out situations which are business critical. It was essential to find a way of preventing Television Centre going ‘off-air’ again and it required the BBC’s governing board approving £10 million to secure effective and continuous transmission.

Looking back, it was the fastest capital approval I had ever secured from a board and it demonstrated to me the importance of really understanding what is critical to the business, not what our CAPEX limits are or what technical considerations need to be considered – the problem just needed to get sorted! After all, ‘the show must go on’ and part of the workplace team’s remit was to demonstrate to broadcast colleagues that we understood them and their requirements.

To this end we brought in experienced BBC veteran Jim Brown to help us understand the nature of TV studios and how they worked. Jim had been Chief Operating Officer (COO) of BBC Resources, which includes delivering studio services, outside broadcasting and post-production. As part of a multi-national team, he also led the resources and IT rebuilding of broadcasting infrastructure in Sarajevo after the Balkan War so I figured if he could manage bombed-out TV studios in a war-torn region, there was some hope he could help us with the tough journey of rebuilding trust among the BBC’s broadcasting community.

It’s All About the Money!

In order to deliver ‘BBC 2020’ property vision the Corporation had to figure out how to deliver all their goals in a world where it was not possible to use capital markets to fund the upgrade. Since 1991, the UK Treasury had imposed a borrowing limit of £200 million on the organization. Furthermore, these funds were prioritized as general working capital to finance programme-making. Also, part of the BBC’s ‘2020 vision’ aside from upgrading its buildings was to find the optimum way to work as an organization and to change how it related to its audiences.

The BBC took a novel corporate finance approach and some highly creative thinking to secure investment for their property transformation. The solution was found by establishing a public/private partnership in which the Corporation could transfer its property portfolio into a partnership, while retaining a 50 per cent interest. The partnership would raise funds for the capital investment and, as part of the arrangement, the BBC would not incur any additional expense above current property costs.

In 2001, following an options appraisal, the BBC agreed to a £2.5 billion partnership with Land Security Trillium. Under the scope of the joint venture, Land Securities Trillium would be responsible for managing the BBC’s property redevelopment programme across the UK, provide finance for new construction and undertake FM and other property services for the Corporation over a 30-year period.

The BBC, along with other public service organizations at the time, was at the forefront of large-scale public/private finance schemes. These schemes, known as the Strategic Transfer of the Estate to the Private Sector (STEPS) and the Private Sector Resource Initiative for Management of the Estate (PRIME), meant that accommodation and its management transferred to the private sector. Other major projects such as the Channel Tunnel rail link linking the UK to France and British Intelligence’s GCHQ building among others were also funded this way. However, in contrast to the other deals, the BBC opted for a significantly different approach, which involved a phased agreement to transfer the freehold estate on a piecemeal basis.

This proved to be a very useful move for the Corporation and the initial project for Phase 1 of the BBC/Land Security Trillium’s Property Partnership was the new White City campus in West London, known as the Media Village. During these early days of the partnership, the BBC learned that it could secure cheaper finance by taking advantage of the bond market and the historic low rate of interest being charged. When the funding for Broadcasting House, the BBC’s Central London HQ, was presented for review in 2003, the BBC had two options: finance via Land Securities Trillium or through the bond markets. While the latter proved to be cheaper, such a decision challenged the reason for having the property partnership.

In removing the need for a partner to finance and own new buildings, the BBC found that the scope of the partnership was reduced to FM and construction management services. It sowed the seeds for a fundamental review of the entire contract in 2005, just four years into its 30-year contract period. As the BBC had invested so much effort in this deal and had 26 years unexpired, I set about trying to find ways to salvage what was truly a sinking ship. ‘Project Prospect’ was set up in a genuine effort to try to find common ground, led by procurement expert Andrew Thornton. As I suspected, hearts had hardened when Land Securities Trillium lost out on taking on big money-making development deals which were more profitable versus run-of-the-mill facilities and construction management. Quite honestly, who could blame them for not taking advantage of better, more lucrative propositions? But for the BBC it did mean that its FM services had to be re-tendered – with the added complication of unravelling a business relationship, envisaged to last for 30 years, in an extraordinarily tight timescale.

Of course, changing course particularly given the nature of the contract, the public procurement constraints and the need to refinance the £341 million 500,000 square feet, the Media Village scheme was not straightforward. The exit negotiations were further exacerbated by the changing rules for financing transactions and increased costs associated with such matters. In the end, White City was re-financed through a bond issue. It all certainly took plenty of juggling, especially since my next adventure consisted of bringing about the BBC’s new mega-projects and aligning the ‘2020 Property Vision’ with its emerging Public Value strategy.

Securing the Delivery of Public Value

Public Value formed the key platform in the manifesto of the newly arrived Director-General Mark Thompson, back in 2004. I imagined that it was a major concern for him in 2005 when he mentioned to me that it was ‘one of the three things that kept him awake at night’ – the other serious one being a whole raft of construction and property-related issues he had inherited.

The run-up to the 2006 Charter Renewal certainly piled political pressure on the BBC, its significance being that the Corporation needs to secure a renewal of its franchise (the publicly-funded licence fee) from the British government. In addition, another layer of scrutiny is added by the external audits carried out by the National Audit Office (NAO), which I generally found very useful, but were hugely time-consuming and fraught with political challenges. Especially as the NAO reports were scrutinized by British Parliament. On a number of occasions, I found myself supporting Mark Thompson and financial director John Smith as we faced some thorough cross-examination from the Public Accounts Committee to account for our decisions and their subsequent expenditure. To my mind, these experiences were akin to what a grilling from the Inquisition must have been like!

Another aspect of working for a publicly funded organization like the BBC is ‘trial by UK press’ and of course there were instances when their blazing headlines about the Corporation’s excesses, inefficiencies and extravagance are justified, but when it came to my particular world, they had a field day. Damning reports abounded on the over-the-top costs of the BBC’s new headquarters, describing it as a ‘citadel of profligacy’, how millions were being squandered on new buildings up north and in Scotland, as well as the wilful misuse of licence payers’ money on moving personnel up and down the country.

I would like to think that it was mostly based on a lack of understanding of what the real estate regeneration was aiming to achieve and the acute problems it was trying to solve. Also, press reports ignored the fact that this was a long-term strategy requiring an enormous initial outlay, which would reap benefits in the future. In fact, by 2016–17, the BBC’s redevelopment project delivered a £47 million annual saving in property expenditure. Nevertheless, back in 2005–06, it was a struggle to find a way to supply and operate a fit-for-purpose portfolio of broadcasting and production facilities, which were functional and safe to work in, plus deliver value for money. Also, they had to meet the expectations of the BBC Board, the BBC Trust (the then supervisory body), under the watchful eyes of its chairman Lord Grade, followed by Sir Michael Lyons in 2006. The following summarizes some of the factors we had to take into consideration:

• Ensure ‘elastic’ or flexible building design which could incorporate the production team’s requirements to steer the constant evolution of new styles and technologies;

• Provide attractive spaces which are available and accessible to the public;

• Keep ‘on trend’ within a highly creative workplace environment in order to retain valuable skills and attract new talent;

• Fulfil the commitments of the BBC Charter to support urban regeneration programmes across the UK.

One of the best decisions I took at the time was to establish a comprehensive portfolio management framework and the formulation of a ‘corporate property plan’. It became the cornerstone of the transformation and an overall roadmap to help us navigate through what seemed at the time an ocean of stormy waters, made all the more difficult by the relentless spotlight of public scrutiny that we encountered along the way.

The BBC also launched its ‘Creative Futures’ project in 2005–06, which aimed to streamline its operations and prepare the Corporation with the right resources and technology for the digital age. This effectively shifted the project emphasis from being focused purely on the buildings to being aimed at delivering major business transformation in support of the ‘Creative Futures’ strategic agenda.

The ‘Creative Futures’ initiative did encourage me to persist with my efforts for a better alignment with the business of broadcasting: by securing an adjustment to the 2020 estate strategy by linking it more coherently with the BBC’s ‘Creative Futures’ produced by Mark Thompson as his strategy to deliver public value. The physical manifestation of this was a corporate property plan based on streamlining the entire estate into eight major hubs. This made sense to me, given that BBC technology had just invested in creating high-speed fibre links between the eight hub locations in Belfast, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Salford, London’s Broadcasting House and White City.

Sources

1. ‘decent quality architecture across the whole estate’.

Jackson, N. Building the BBC, A Return to Form, BBC London, 2003. p.14.

2. ‘the organization had made good progress in rationalising (by almost a third) and upgrading its estate. It had also improved its use of available space’.

NAO Report. ‘Managing the BBC’s estate’. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, 2014, p 10.

3. ‘citadel of profligacy’.

Scott, P. (2013) ‘The citadel of profligacy... or how the BBC flushed another £200m of your money down the drain’. Daily Mail https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2337744/The-citadel-profligacy--BBC-flushed-200m-YOUR-money-drain.html

Epigraph to Introduction

Reith, J.C.W. Broadcast over Britain. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1924, p. 24.

Notes

7 The Hutton Inquiry was a judicial investigation into the death of biological weapons expert Dr David Kelly, who died in questionable circumstances, after he was exposed as the source of a BBC news report alleging that the then UK government, under Prime Minister Tony Blair, had ‘sexed up’ a dossier making the case for going to war in Iraq. The inquiry cleared the government of wrongdoing and dealt a damaging blow to the BBC’s journalistic integrity, criticizing the Corporation for failing to check the story adequately, which resulted in the resignation of the reporter who broadcast Dr Kelly’s findings. This was swiftly followed by the departures of the Director-General and Chairman – the aftermath of the Hutton Inquiry was described as ‘one of the worst in BBC history’. (Quote source: ITV).

8 A high-performing team is one which shares a common vision and goals by collaborating, challenging and holding each member of the team accountable. Thus generating greater commitment, in order to achieve outstanding results.