Delivering Agile Workplaces Across the Nation

You must try to do something that really works for the people who are going to be in the building, and for the community who are going to have to live around it.

Kevin Roche, Architect

With the 2006 Charter Renewal coming up, one of the fundamental concerns licence fee payers had expressed was that the BBC had to shift away from its London bias and represent all of Britain in its broadcasting. While a move out of London had been on the cards for some time, Director-General Mark Thompson recognized that a new base in the north of England could help the overall transformation programme, one major element being the relocation of five BBC divisions from London to MediaCityUK in Salford, near Manchester.

During the following few years I became a regular visitor to the BBC Executive Board, particularly since the BBC’s central London flagship project Broadcasting House, which had an overall budget of £1 billion, was in troubled waters. Additionally, the BBC had to upgrade a great deal more of its property portfolio to meet the goals of its ‘Creative Futures’ directive, with a plan of not only improving its buildings, but also opening up the BBC to its audiences the length and breadth of the UK.

The ‘Project England’ scheme provided new upgraded digital facilities to local radio stations in all regions. About 16 new spaces were launched during this period, each comprising roughly 10,000 to 20,000 square feet, with each one having the usual challenge of constructing new workplaces and installing complex digital broadcasting kit.

In contrast to the old-style BBC, which had typically operated behind closed doors or high, forbidding security fences, these new amenities were located in city/town centres and welcomed audiences into specially designed ground-floor public areas. The list of new facilities opened tells its own story: Birmingham, Cambridge, Coventry, Hull, Leeds, Liverpool, Leicester, Norwich, Southampton and Stoke among others.

Aside from the decision to move some operations up north to Manchester, Scotland and Wales were also factored into the transformation. BBC Scotland had been clamouring for years for a new home to replace its Victorian base in Glasgow, which had been established in the 1930s. Cardiff, the capital of Wales, became the setting of a new totally digital 175,000 square feet complex, Roath Lock. A drama factory which produces the world’s longest-running medical series, Casualty, and the classic sci-fi programme, Doctor Who.

Pacific Quay – Scotland Sets the Scene

Pacific Quay in Glasgow was the first of the mega-projects which took the BBC from analogue to digital. It was a significant milestone when it opened in 2007, since it was Europe’s first end-to-end digital production facility. It also heralded the BBC’s transformation away from the traditional world of content and tapes to the new one of a fully digital broadcasting platform.

The decision was made that BBC Scotland’s existing Queen Margaret Drive (QMD) property in central Glasgow was too costly and complex to redevelop and would also involve considerable disruption to its ongoing production and broadcasting activities. Aligning with the BBC Charter’s commitment to support urban regeneration, a derelict dockland site on the banks of the Clyde, a few miles south of Glasgow, was approved in 2004. It provided the perfect location for the 364,000 square feet Pacific Quay development, which houses 1,300 staff. It also opened a fresh chapter for the BBC in Scotland, not only in constructing a new building, but also for inspiring a new way of working.

Having learned the lessons from the development of White City in London, the project was financed via a bond issue through Barclays Capital rather than Land Securities Trillium. Under this arrangement, the bondholders own the building, with the BBC holding the 30-year lease. The total capital costs of the development were £188 million, partially offset by the sale of the old BBC Scotland site for £18 million. Land Securities Trillium was assigned to oversee the design team, with Bovis Lend Lease as the main building contractor.

Following an international competition, the BBC appointed distinguished British architect David Chipperfield, who provided the architectural ‘wow’ factor, as well as incorporating acres of open space into the design, which was very different to the nooks and crannies of the old Victorian QMD building. It was all open plan, including the space occupied by the Director of BBC Scotland, and this in itself sent a clear signal to everyone that things were really changing.

Pacific Quay was a great opportunity to see how the organization grappled with moving not just into an open-plan office environment, but also in coping with the digital world. There were many concerns about how to make programmes with this new capability, including some industrial relations issues and the usual fear of the unknown. Of course, it all worked out in the end, as workflows were changed and people embraced the new-fangled technology. More pertinently, the project also supported BBC Scotland’s efforts to achieve a 25 per cent reduction in its cost base over five years by embracing change, which was a higher target than most other parts of the BBC.

Pacific Quay owed its success to a strategy which I supported, in that it was organized as part of a comprehensive change management programme rather than just a building project. It was under the overall management of a Programme Director who spanned technology, construction, operations and transformation. The development also thrived under the leadership and executive sponsorship of the Controller of Scotland, Ken MacQuarrie, who held a strong vision of the transformational powers of technology and his management support was key in successfully aligning co-operation across multiple BBC departments. The building was also designed to provide significant public access, delivering on the BBC Charter commitment to engage communities by encouraging open admission to its facilities and live broadcasts.

New Broadcasting House – The Journey to a Creative Powerhouse

In 2000, the BBC published its London Three Hub property strategy, which was a portfolio optimization programme recognizing the upcoming issues of expiring leases and other property concerns in the capital. This meant closing Bush House, the HQ of the BBC World Service, a distinguished 1930s building in the Strand, now part of King’s College, London. Additionally, several smaller buildings were closed to enable operations to be consolidated within fewer sites. As a consequence, the organization’s iconic Central London W1 Broadcasting House, its flagship since 1932, would now house national and international radio, television and online journalism, including the World Service, all under the same roof.

FIGURE 9.1: BBC Three Hub London Strategy

This ambitious project, with a capital value of £1 billion, presented a number of enormous and very complex challenges, as well as numerous logistical and aesthetic problems. The brief being that the legacy of the original heritage-protected Art Deco Broadcasting House had to be retained, while adding a twenty-first-century state-of-the-art production base for the BBC, with capacity for 6,000 employees, across the whole campus. Moreover, Broadcasting House is located in an architecturally sensitive area, surrounded by 13 other heritage-listed buildings, as well as being situated in a congested city centre, off central London’s main shopping thoroughfares. Maintaining good relations with all our neighbours throughout the regeneration became a full-time job for Robert Seatter, the BBC’s Communication Manager at the time, given its highly complex nature.

The other disadvantage was that the site is built above the London Underground network and the studio floors in the basement had to be spring-loaded to dampen the constant vibrations of Underground trains passing underneath. Especially important since broadcast quality and continuity had to be ensured, as the BBC’s main radio networks based at Broadcasting House had to be kept on-air throughout the redevelopment programme.

Construction on this ‘Grand Project’ began in 2003. A big-name architect – Sir Richard MacCormac – was retained, along with London Securities Trillium for the capital programme management (design/construction/build), while Bovis Lend Lease was appointed as the main contractor. The project was financed via a bond issue to raise the £813 million, with the BBC contributing the additional £232 million and everything seemed set for what was to be an eight-year project carried out in two phases, to be delivered in 2011. However, things did not go quite to plan as Broadcasting House welcomed HM the Queen to open the second phase of the redevelopment in 2012!

Undoubtedly a project of this magnitude is fraught with difficulties; but back in 2003, a year prior to my arrival, the problems hit epidemic scale. Two major sub-contractors providing glazing and stone cladding went bankrupt, the 2001 terrorist attack prompted a re-think of security and safety specifications and to cap it all, the refurbishment works uncovered defects in the structure of the original Broadcasting House building. Added to this and on a sad note, the project director was struck down by a fatal illness, which left the redevelopment in caretaker hands at precisely the wrong time. Plus, the relationship with the developers and contractors had hit an all-time low, with the inevitable contractual disputes fuelling the fire.

The urgency and scale of the issues at Broadcasting House were the critical items in Mark Thompson’s in-tray when he took over the helm of the BBC in 2004. Solving them almost certainly contributed to many sleepless nights for him and for me too. Nevertheless, I suggested applying a fresh approach based on a three-step strategy:

• Restructuring the BBC client project team and introducing additional resources;

• Re-negotiating the development agreement to re-base the budget;

• Reviewing the design to simplify the specification and reduce costs.

At the time, what I also found overwhelming was having to deal with not one, but two potentially major contractual disputes, although it did provide me with a crucial learning point – not just opting for what appeared to be the only course of action. Even though lawyers galore were queuing up to offer the BBC their services, no doubt attracted by the rich pickings of a lengthy legal dispute.

Thankfully, through the wise counsel of external advisor Jonathan Harper, we managed not to go down the conventional route to resolve these issues. Since one of my aims was for BBC Workplace to act as an intelligent client, I suggested to BBC Legal Counsel that a full-time in-house legal advisor was needed. This request brought Peter Farrell, now Head of BBC Legal, into my life, who proved to be an invaluable asset.

I also took another unusual step with another instrumental appointment, a former Disney colleague of mine Keith Beal, who was an experienced production expert and understood broadcasting. He helped re-shape and re-energize the project team and played a pivotal role in stabilizing what had turned into a hugely problematic venture. Having steadied the construction side of the Broadcasting House project, Keith shifted his focus to help with the BBC’s move up north to MediaCityUK.

The other turning point in terms of the Broadcasting House Project team was to beef it up, but not in a conventional manner. Broadcasting House Phase 1 was run as a pure construction project, yet in my mind, I always saw the regeneration of Broadcasting House as a major link in the BBC’s content creation capability and one that relied heavily on technology. Therefore, as the second phase was being reshaped it provided the perfect opportunity to set it up as a fully-fledged change management programme. Until that point the BBC never had to face the challenge of moving so many live programmes into a new building, with the added complication of adapting to new technology.

The Corporation realized that the organization needed to ‘up its game’ and embrace programme management wholeheartedly. To this end it created a specific Corporate Programme Management office to underline the importance of this function. Again, it was another positive way in which BBC Workplace reinforced its strategy as an intelligent client; by playing a part in nudging the Corporation in this direction and helping with the selection of the first BBC Corporate Programme Manager.

With Phase 1 completed and with construction of Phase 2 in a better place, it was time to focus on change management. In 2009, it was Head of Journalism Mark Byford who persuaded Andy Griffee to take on the onerous task of becoming full-time Programme Director for Broadcasting House and to effect its smooth transition. A broadcaster and dyed-in-the-wool BBC journalist with 25 years’ experience, Andy had been Controller of BBC English Regions for nine years. This meant he had to switch from dealing with the sharp end of editorial output and immerse himself in the unfamiliar world of project management and finding the best way to maximize the efficiencies of co-location. Yet this appointment was significant since it sent a clear message to a sceptical broadcasting community that BBC Workplace took their issues on board and understood the way they worked.

Andy is a good example of an agile person transferring his skills to another sector, but also realizing that the brief required a holistic approach by bringing together editorial, property and technology in terms of how they all functioned cohesively for the benefit of the organization.

It would have been very difficult to deliver the Broadcasting House projects without Andy Griffee as overall Programme Director, together with effective collaboration from BBC Workplace’s London Property Director Andrew Thornton (sadly no longer with us) and Director of Technology Andy Baker. They achieved the impossible by facilitating the move of 5,539 people from ten buildings across London, integrating them into the four that comprised New Broadcasting House. The migration schedule began in January 2012 and spanned 75 weekends of staff moves. This also involved providing 41,886 training days and 126 different courses, so that BBC personnel could familiarize themselves with the workings of the new technology and renovated building.

In hindsight, Andy commented that managing the transition at Broadcasting House was ‘the most stressful and high-stakes job I ever undertook’. He also pointed out that his respect for Broadcasting House and the role it played in BBC history motivated him in undertaking this ‘once-in-many-generations’ opportunity to make my imprint on its next chapter and the future of a major chunk of BBC output’.

With a stable team in place and a plan to resolve the project delivery issues, the other aspect was to engage with the various professionals who would inhabit the new facility. They were identified as three distinct tribes: News, World Service, Audio and Music, all requiring bespoke technologies and distinct working practices. The key was to identify ‘cultural’ or ‘team’ differences and align these idiosyncrasies within a change management programme. They also needed encouragement to embrace new ways of working in a shared space, using common technologies. Aligning different working cultures is never an easy journey, but it is always worth investing time and effort in delivering shared solutions.

When the original plans were drawn up, the architects, designers and BBC Executives responsible for the Broadcasting House redevelopment had little idea how rapidly the pace of technological change would transform broadcasting and most people are unaware of how unique this gloriously distinctive building is in fusing the BBC’s past with the present and the future. At the time of its completion, I remarked, ‘Broadcasting House is not only a building for the BBC, but for London and for Britain.’

It still astounds me that it is responsible for half of all the BBC’s output. It houses Europe’s biggest newsroom and broadcasts globally 24 hours a day, every day of the year. The new building’s central area fits 70 double-decker buses and all of the floorspace equates to 10 football pitches. In the end, despite the multitude of problems, construction cost £31 million less than the £1.05 billion stated in the 2006 budget. New Broadcasting House has trebled the financial benefits first identified in 2002 by up to £736 million over the remaining 21-year life of the bond.

The rationale for redeveloping New Broadcasting House and the validation for its transformation came from the actual people working there, by giving them a workplace which enabled them to operate together as a coherent unit. Journalists and broadcasters could now easily obtain the most comprehensive view of a news story or an unfolding situation by being able to access or meet up with colleagues from all corners of BBC journalism.

Award-winning BBC News broadcaster and Radio 4 Today programme presenter Mishal Husain remarked at the time, ‘Being under one roof is an amazing moment for all of us in BBC News. It’ll showcase our strength to the outside world and it’ll create an amazing internal talent pool, so if I’m working on a story, someone who will know that story inside out will be right there, within arms’ reach.’ Nonetheless, I will leave the last word to veteran former BBC News journalist John Humphrys, who has quite a cynical reputation. His comment on the regeneration of Broadcasting House was that, ‘It wasn’t going to work. I thought things would go wrong endlessly and it didn’t happen. It was pretty damn near seamless, I must say!’

MediaCityUK, Salford – Placemaking at Scale

The ‘Out of London’ policy was confirmed in an announcement at the end of 2004 and it signified that five London-based departments: BBC Children’s, BBC Learning, parts of BBC Future Media & Technology, BBC Radio 5 live and BBC Sport, would transfer to the north of England, with Manchester being the preferred location. However, it would require a novel approach to secure the viability of such a large relocation out of London and inspire employees with the attraction of the ‘Magnetic North’. This initiative envisaged the creation of a media zone, with the BBC as the anchor tenant, which would also appeal to other creatives in its aims to compete on a global scale.

This found me spending a day back in 2006 with Director-General Mark Thompson, showing him around the four proposed sites shortlisted for the project. When we drove into the 37-acre wasteland of disused and neglected docklands by the Manchester Ship Canal at Salford Quays, on a windswept, grey October morning, he looked perturbed. Who in their right mind would choose this out-of-the way derelict site in favour of the better-located options in the city centre?

Despite the obvious shortcomings, on walking around, he changed his mind when he recognized its potential symmetry coming from a cultural value perspective. What Mark had spotted, which nobody else had, was that the site formed the third apex of a triangle around Salford Quays. The other two were occupied by The Lowry arts complex, comprising two theatres, a drama studio and a museum dedicated to one of Britain’s most recognizable artists, northerner L.S. Lowry, who was a renowned painter of industrial and landscape scenes. The Imperial War Museum North formed the second apex. This was housed in an evocative award-winning building designed by Daniel Libeskind – a popular destination which by 2005, three years after its opening, had already received its millionth visitor.

‘What better neighbours could Britain’s best cultural icon have?’ Mark quipped, as he surveyed this ramshackle expanse of land by the canal and imagined the BBC completing the impressive, yet edifying triangle.

Ironically, and what has never been commented on so far, is the genesis for MediaCityUK did not come from Salford itself, but from Manchester City Hall. This was due to the visionary leadership of Sir Howard Bernstein, then CEO of Manchester City Council. He came up with the idea of creating a media zone which fitted nicely with the BBC’s ‘Magnetic North’ vision for the move out of London. Howard then facilitated the ‘impossible’ by bringing together arch-rivals the BBC and ITV to come together and explore the concept of working together, through a series of brainstorming sessions. This was made easier as one of the potential site solutions was commercial broadcaster ITV’s existing site.

The plot thickened with the arrival on the scene of Manchester’s neighbour Salford, who had an optimum site, coupled with a hyper-dynamic regeneration body led by Felicity Goodey – who had led the team responsible for funding, building and operating The Lowry gallery and theatre centre. This proved to be a powerful combination for the other competing sites and much to Howard’s disappointment, the media city concept was lost to Salford.

So, Salford City Council granted planning consent for a multi-use development on the Quays, involving residential, retail, studio and office space, under Felicity’s indefatigable leadership, who engineered a remarkable cocktail of talent and like-minded partners to create a twenty-first-century city in record time. She led the consortium, which built MediaCityUK, consisting of the developer Peel Holdings, Salford City Council and the North West Development Association. They worked together with the BBC, local businesses and the neighbouring Lowry complex. This proved to be a great example of public/private partnership working in harmony towards a common goal.

Additionally, as this was solely a lease agreement, the BBC did not have to raise capital for the Salford project, which meant that it did not incur any direct building-related costs outside rent. So, the funds released from leasing were assigned to investing in programmes and people, especially the costs of relocating employees from London. This was a crucial factor because previous attempts to decentralize production out of London had led to significant talent loss as people became tired of commuting from their home base in the capital. It was essential to the success of the project that BBC North could attract and retain talent by helping them find reasons to transfer to Salford, rather than inventing pretexts for them not to move up north.

That flexibility and effective use of space is evident throughout the facilities at BBC North and it has enabled different and creative ways of working. This is due in part to the COO of BBC North at the time, now Director of BBC Children’s, Alice Webb and her insistence that nothing should be attached to the fabric of the building on a permanent basis. The absence of fixed walls and signs demarcating territories allows for more effective use of space since programmes can shrink and grow their footprint depending on production requirements. Also, people at BBC North are used to sharing space and resources so when BBC Children’s need laptops for a weekday event, they borrow them from BBC Sport, who only need them at the weekend.

Currently, there are around 3,200 staff working in 26 departments, producing thousands of hours of content for BBC television, radio and online; broadcasting the nation’s favourites, such as Blue Peter, the annual telethon Children in Need and the hugely popular football show, Match of the Day.

The success of MediaCityUK was further underpinned by ITV confirming plans to use the studio block, as well as lease office space and relocate production of the UK’s longest- running, popular prime-time soap, Coronation Street, to a new studio lot on the opposite side of the Manchester Ship Canal. MediaCity is now considered ITV’s flagship facility, with a staff of over 750 working for the UK’s biggest commercial programme provider, hosting factual, entertainment, drama and post-production.

It has also become home to an eclectic and exciting mix of over 200 businesses, which are fuelling the ‘northern powerhouse’ – global brands such as Kellogg’s and Ericsson, as well as dock10, the UK’s premier television and post-production facility, and SIS, the world leader in broadcast gaming and retail betting. Shops and restaurants have been attracted to the waterside location and there is now a constant ebb and flow of visitors to the site.

The appeal of MediaCityUK was behind health insurance conglomerate BUPA’s decision to stay in the same area but move their HQ ‘up the road’ from their present Salford Quays site to this dynamic multi-dimensional neighbourhood. This demonstrates that management are seeing and understanding that their organization’s future success lies in an ability to attract and retain talent by providing amenities near or in a convivial and vibrant setting. However, MediaCityUK is not just about the ‘big players’. At its core is the Landing, a hub for high-growth technology and digital start-ups, scale-ups and SMEs, incorporating 120 future-focused businesses. This environment is certainly a breeding ground for creativity, especially for the 1,500 students using the state-of-the-art facilities at the University of Salford. Additionally, Salford City College, University Technical College and the Oasis Academy have also made MediaCityUK home and are all fostering beneficial relationships with the companies around them as they develop the next generation of technological, digital and creative pioneers.

Mark Thompson had originally envisioned the siting of the BBC at Salford Quays as a complement to the ‘cultural triangle’ of The Lowry and the Imperial War Museum North. It has morphed into a ‘cultural and social pentagon’, which now includes the UK’s two major broadcasters, the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as Salford University.

The BBC was certainly the impetus for the regeneration of this run-down area on the banks of the Manchester Ship Canal. What Mark could not have foreseen on that blustery day in October 2006 was that the BBC move would bring 4,600 new jobs between 2011 and 2016 to Salford. Added to that, according to an independent report carried out by KPMG in 2015, the BBC’s relocation contributed £277 million to the UK economy (as measured by Gross Value Added) in just one year.

Television Centre, White City – the BBC’s Cinderella did go to the Ball

The venerable epicentre of the Corporation might be Broadcasting House, but for over 50 years, the real BBC magic was created over at Television Centre in West London. When it opened in 1960, the BBC’s broadcasting and talent factory was one of the first purpose-built centres for television production, as well as being one of the largest in the world.

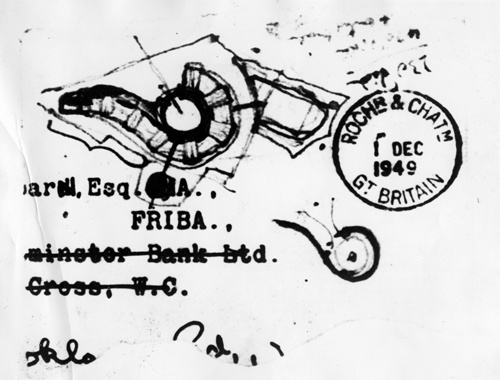

It was designed by architect Graham Dawbarn and the story goes that while seeking inspiration for the project, Dawbarn took the 50-page brief to a local pub, pulled out an envelope and drew the outline of a large triangle to mark the perimeter of the site then inserted a question mark in the middle of the triangle almost as though he had no idea what to do. As shown in Figure 9.2 below, this simple sketch featuring Dawbarn’s sign of uncertainty provided an ingenious solution to design a space with eight studios, production galleries, dressing rooms, camera workshops, recording areas and offices. The tapering effect of the ‘question mark’ allowed for further expansion, if required.

(Image: BBC)

FIGURE 9.2: Dawbarn’s first design for the BBC Television Centre captured on the back of an envelope.

Increasingly, over the years various extensions were added and the BBC effectively ended up ‘colonizing’ White City in the following decades, with the addition of six further buildings, all located within easy walking distance of Television Centre.

This sizeable complex, which eventually became Media Village W12, totalled 2 million square feet and occupied around 35 acres. It featured substantial facilities, such as White City One, a 350,000 square foot office building – its brutalist Soviet-style architecture earned it the unfortunate nickname ‘Ceausescu Towers’ after the despised Romanian dictator. The complex also included Woodlands, home to 1,300 staff working at BBC Worldwide. Not to be confused with BBC World, this division was responsible for selling BBC productions across the globe.

For five decades the image of Television Centre dominated the BBC’s news output. It was regarded as one of the nation’s favourite buildings, as well as being the familiar embodiment of ‘Auntie Beeb’. This major BBC campus was home to 12,000 people involved in producing some of Britain’s best-known television programmes, such as the original Doctor Who series broadcast for the first time in 1963, the day after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. So many popular and internationally-acclaimed TV shows were conceived and filmed there, including classics, such as Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Blue Peter, The Forsyte Saga, I, Claudius, Play for Today, Dad’s Army, Fawlty Towers, Top of the Pops and Yes Minister/Prime Minister. More recent productions include Top Gear, Only Fools and Horses, Blackadder, Keeping Up Appearances, Absolutely Fabulous and Strictly Come Dancing (known as Dancing with the Stars in other countries) to name but a few. Not forgetting the numerous political, children’s and sport programmes, as well as breakfast, music, variety and talk shows, fund-raising telethons, etc.

All production was in-house, which required an army of personnel, from camera operators, producers, directors, screenwriters, script producers and editors, sound recordists, lighting technicians, production, costume and set designers, art directors, make-up artists, hairdressers, props builders, post-production and sound editors, visual effects and music supervisors, etc. – all departments requiring numerous assistants, administrative and support staff to maintain the smooth running of this global TV talent factory.

Television Centre also housed the nerve centre of the BBC technical system, including the Eurovision network, which although part of the European Broadcasting Union, includes 75 broadcasting companies worldwide. I still recall Mike Eaton, Television Centre’s Duty Manager, showing me around the Central Control Room on my first visit, which looked very similar and just as complex as NASA’s space launch HQ. Underneath this convoluted set of buildings were thousands of miles of cables, which had expanded over the years and the ducts were overflowing with an ocean of colourful spaghetti. When Television Centre eventually closed in 2013, the salvage value of all this copper cabling generated a sum in the millions.

Depending on who one talked to at the time, Television Centre was either a sacred part of the BBC brand or an asbestos-filled labyrinth of costly real estate. Its original purpose as the world’s largest production factory had already had the rug pulled out from under it as far back as the early 1980s. With the arrival of more technically sophisticated filming processes, this meant that many programmes could be made on location and much of the production space had become redundant. Another contributory factor was that Television Centre was still very much an ‘old-school’ multi-camera, video-production facility and most drama (except soap operas) had shifted onto film or single-camera video recording.

Another issue for me to consider, aside from English Heritage listing parts of Television Centre in 2008 and assigning it special status since it was of ‘undeniable national interest and one of very few monuments to television history’ was that I was dealing with something intangible beyond merely bricks, mortar and property values. This was brought home to me when it came time to move the popular Blue Peter Garden from London up to Salford. The garden was a feature of the long-running children’s TV programme and was also the burial place of many of the show’s beloved pets and included a statue of its first dog, Petra. The thought of relocating the remains of all these childhood favourites perplexed many viewers and caused widespread consternation.

Despite its many idiosyncrasies and the enormous cost of keeping Television Centre open, the BBC had soldiered on with this colossus for many years prior to my arrival. From 2010 onwards, figuring out the future of the BBC’s much-treasured Television Centre felt like being caught in the crossfire of a brewing civil war. It was certainly a challenge to provide both public value and craft a sensible solution for this gigantic campus, riddled not just with structural problems and asbestos, but fraught with internal politics as well. There were many times when I almost threw up my hands in despair since there seemed to be no light at the end of the tunnel. However, the skills and experience gained from working on MediaCityUK gave me the tools to view the Television Centre project as potentially about innovation and placemaking, coupling the emotional connection people had to the BBC and its place in White City.

First, since the BBC had defined the eight major hubs around the UK, BBC Workplace had the overall strategy of moving 12,000 people around the estate. The question was: where would Television Centre fit into all this? Already from the 1990s, some Television Centre productions were being crewed entirely by freelance staff. By 2011 almost all the technical operators had gone, replaced by independent professionals. Freelancers were increasingly employed in the design, wardrobe, hair and make-up departments, so there was no real need to house and cater for a vast army of in-house production personnel.

As BBC Workplace had moved ‘upstream’ strategically, it had acquired a much better grasp on occupancy levels and had developed the ability to advise the BBC Executive board using real data, rather than merely speculation. This was a first for the organization as it removed the ability of the various production divisions to make unjustified claims for space and resources.

In 2007 the inevitable conclusion was reached by the BBC Executive board that Television Centre was to be closed and sold so a coherent strategy had to be figured out, not just for Television Centre, but also for the five other facilities which made up the BBC’s White City campus. A dedicated group was formed from BBC Workplace to tease out the myriad of issues involved in the closing and sale of White City, called the Major Asset Disposals team. Known by its acronym MAD – obviously somebody somewhere had a great sense of humour! However, to be fair to the MAD team they did frame a strategy based on a phased withdrawal of the BBC from its position as the dominant occupier in White City. This involved a move down to about 4,000 people from 12,000 and this was made possible, in part, by the introduction of agile working practices across the BBC’s workplace.

Additionally, from 2007 until 2009 decisions had to be made in shaping the portfolio optimization strategy for this vast 35-acre White City estate with the heritage-listed ‘doughnut’ Television Centre sitting as the single biggest surplus asset. Plus, dealing with the reality that the general consensus of the property market considered White City as a ‘BBC desert’ and not particularly appealing to other occupiers. Further adversity piled on with the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis, which severely dampened interest in commercial real estate at that time. All this conspired to add to the difficulties of disposing surplus property in a neglected, unglamorous and depressed neighbourhood – BBC White City was indeed the proverbial white elephant!

The only option for the BBC at the time was to mothball large swathes of real estate in London and just hope for an improvement in the years to come. It was a great price to pay but there seemed to be no other viable course of action. Consequently, the MAD team was disbanded and a complete rethink in approach was required.

Funnily enough, it was Walt Disney who proved to be my inspiration in engineering how the BBC’s ‘Cinderella’ could go to the ball. During my early days at Disney, I was part of the Imagineering team, which is the research and development division of the Disney empire, responsible for the conception and construction of its attractions and theme parks worldwide, as well as the organization’s real estate management. It was at the corporate HQ in Burbank, California, in a cluster of industrial buildings that a rather wet-behind-the-ears, former chartered surveyor met some of the most creative minds in the world. Undoubtedly, I was enthralled by the world of Disney and working with fellow Imagineers and their talent for ingenuity and resourcefulness encouraged me to think differently and follow Walt Disney’s mantra: if you could dream it, you could do it!

I needed to stand back and take a fresh look at how the BBC’s Gordian knot of a problem could be cut. So, one day I went up to the highest floor of the Television Centre complex and looked around the entire neighbourhood. Indeed, I had one of those rare eureka moments – in order to secure the disposal of BBC surplus assets, the whole of the White City area had to be reimagined or re-imagineered to make it more attractive. This led me to develop a methodology called ‘Land + Brand’, which was subsequently refined into the Smart Value formula, and it comprised of three core principles:

• Optimizing the disposal of Television Centre by harnessing the power of the BBC’s iconic brand;

• Consolidating all the other BBC facilities in one campus through agile working;

• Creating a White City marketplace which would be attractive to investors and occupiers, which subsequently turned into ‘Creative London’.

Serendipity did play a major part in helping me to see things in a different light. While I was looking down across the ‘BBC desert’ from on high, I could not help but notice the scale of our new neighbour the Westfield shopping complex, which had recently opened in 2008. At the time it was the largest shopping mall in London. A decade later it attracts over 30 million people per year and has over 360 retailers across its 2.6 million square feet of lettable space, now making it the largest shopping centre in Europe.

Looking at the vast expanse of Westfield London took me back to the Disney Imagineers’ playbook and to the creation of Disneyland Paris. While everyone knows about the famous theme park, very little is known about the wider picture and the Walt Disney Company’s involvement in the creation of a new town – Marne-la-Vallée – and the Val d’Europe shopping outlet, which opened in 2000. It was designated an ‘international tourist destination’ by the French government in 2016 for its capacity to attract 15 million people annually. To put this in perspective, that other great Parisian landmark, the Eiffel Tower, welcomes 7 million visitors per year.

This connection between Disneyland Paris, Marne-la-Vallée and the Val d’Europe shopping mall framed my views of placemaking for White City from a corporate perspective. It was my impetus for reasoning that if 23 million people visited Westfield shopping mall in its first year of opening alone, surely some of them might see the Television Centre neighbourhood as an attractive place to live or work in. Could the nostalgia factor of those well-known and much-loved BBC programmes move people to buy into the area? Or perhaps the buzz associated with Television Centre’s glory days producing prime-time TV shows starring so many famous names? Could the allure of the BBC brand be harnessed to attract people to White City?

As a result of my rooftop inspiration, BBC Workplace went back to the drawing board to come up with an alternative approach and devised a product development exercise based around my ideas for a demand-led scheme, which would leverage the value of the BBC brand. Labelled ‘Smart Value’, it aimed to develop a mechanism for collaborating with a developer partner to optimise the value of both the BBC brand and its land. In parallel, BBC Workplace also tried to improve the market’s appreciation for the wider White City area.

In May 2010, we presented an ambitious new proposal called ‘Creative London’, where White City anchored by a re-purposed Television Centre could become the conduit for a multimillion-pound urban regeneration project to transform a deprived area of West London, which had been hit hard by the recession, and turn it into a vibrant, new ‘creative London quarter’.

The concept was an evolution of what the BBC had achieved in Salford with MediaCityUK, which meant that the Corporation would work as a catalyst in collaboration with public and private partners. The aim was to build a showcase creative media hub for London around the adjoining White City estate. In this way the BBC would still retain a presence on the historic Television Centre site by leasing studio and exhibition space, while providing opportunities to promote the creative sector. The development of the area would replace dilapidated buildings with exciting new spaces for independent production, media and arts companies.

The ‘creative quarter’ concept, while more complex than merely selling off the BBC’s White City estate to a developer, presented exciting opportunities for the Corporation to align itself with its original ‘Creative Futures’ agenda. It also endorsed the BBC’s obligation to deliver both economic and public value, with the added bonus of creating social value in this neglected part of London.

In January 2011, the BBC approved a twin-track approach to the disposal, which called for the market testing of ‘Smart Value’ alongside a conventional freehold sale to identify whether this approach would drive out additional value to its White City properties. As if that was not difficult enough, the BBC made life even more challenging by inserting further business expectations into the equation:

• Maximize value to the Corporation;

• Minimize risk during the handover from the BBC to the new owner;

• Protect the legacy of Television Centre.

In 2012, the BBC sold Television Centre to property developers Stanhope Plc for £200 million. The BBC retained the ownership of the building, but sold the lease with the understanding that this could be bought by Stanhope at some point in the future and in this way, the BBC would also take a share of future profits from the development. The joint venture of the BBC and Stanhope formed Television Centre Developments, which was tasked to dispose of the 1 million square foot landmark building and redevelop it into residential properties, in addition to a mix of leisure and office facilities.

BBC TV broadcasting might have moved out of White City, but the commercial side of the organization, BBC Studios (the former BBC Worldwide), responsible for selling BBC programmes operates in the newly refurbished studios, which formed part of Television Centre.

In 2018, BBC Studios returned £243 million (EBITDA) to the organization through its overseas sales, proving its creativity still informs, educates and entertains millions worldwide. The BBC’s other commercial venture Studioworks brought in a revenue of £37 million in 2017/18, by providing production and post-production facilities from the now-renovated, former Studio 1, where many of its hit shows were once filmed.

Other parts of the BBC’s White City complex – Broadcast Central and Lighthouse – also provide office space, broadcast and production centres not just for the BBC, but also for commercial stations Channel 4, Channel 5 and BT Sport among others. Again, giving the BBC a working link to a set of buildings which had played such an important role in its history over the years.

The whole Television Centre site has now been redeveloped, the old car park turned into a landscaped square open to the public and there is a vibrancy about the place as other media companies have moved in, attracted by its numerous restaurants, bars, cafes and cultural activities. No doubt the allure of fashionable private members’ club Soho House, with its rooftop pool and panoramic views over London, is also a great draw.

The original Television Centre with its distinctive doughnut-shaped 1960s exterior has been retained, together with the renovated gilded statue of Helios, the Greek god of the sun overlooking the central rotunda, where he had stood guard for half a century. An emblematic connection to the BBC, Helios sunrays symbolize television radiating around the world. At the base of the monument lie two figures representing sound and vision – a powerful visual reminder that BBC TV’s legacy is still fostering and encouraging a creative environment in White City.

White City – A Placemaking Phoenix Rises in West London

The redevelopment of the BBC’s Television Centre and Media Village W12 was one piece of the jigsaw in the overall regeneration of White City. The other was the enormous transformative impact of Europe’s largest shopping centre, Westfield London, in conjunction with the UK’s premier science and research university, Imperial College. The formidable trio of the BBC, Imperial College and Westfield were the cornerstones which really turbocharged this 60-acre West London site.

To put it all in context and from a property market perspective, in the beginning of the twenty-first-century White City was considered a bit of a wasteland, dominated by the vast expanse of ‘BBC desert’; it was a ramshackle oddity with no real purpose, despite its interesting history. In 1908 the site was chosen to hold the Franco–British Exhibition to commemorate improved Anglo-French relations. The exhibition featured an artificial lake surrounded by a ‘city’ of buildings with white stucco facades, which gave the area its name ‘Great White City’. Later that year, and with the addition of a newly constructed stadium as its centrepiece, the Great White City hosted the fourth modern Olympic Games. The new stadium was designed to be located exactly 26 miles from Windsor Castle, the starting point of the Olympic marathon, and since then this distance was adopted as the standard for all modern marathons.

White City was subsequently used as an international exhibition centre up until World War I, with the stadium eventually becoming a speedway and greyhound racing track. Ultimately, the area took a downmarket turn. White City Stadium was demolished in 1985 to make way for the BBC’s White City complex, now White City Place and the Media Village, W12.

In parallel with the BBC, Imperial College was also facing some significant challenges in its 102-year history, which were defined more by the university needing to maintain its growth and innovation capacity. This was severely hampered by its existing built-up central London campus, which was established in 1893 behind the Royal Albert Hall in South Kensington and was becoming increasingly unfit for purpose.

Like the BBC, Imperial College has an international reputation for excellence – in this case for science, engineering, medicine and economics. It ranks consistently among the top ten universities in the world. This prestigious institution attracts students from 140 countries, undoubtedly drawn in by the fact that its alumni include 13 Nobel Prize winners – notably Sir Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin.

Imperial College realized that in order to maintain its pre-eminent position in the scientific field, collaborating effectively with other experts worldwide was vital. So, attracting and retaining the brightest and best faculty talent, students and researchers was a paramount concern, together with providing them with affordable accommodation in London. One solution to Imperial’s problem of space was buying a vacant lot in White City from the BBC in 2009. At the time BBC Workplace was developing its Smart Value initiative, which would eventually culminate in its plans for ‘Creative London’ and central to its thinking was taking a more holistic approach to master-planning in White City. This meant devising ways to engage with neighbouring landowners to present a unified front to the local Planning Authorities. I was helped to persuade them to buy into this unusual approach by the BBC’s long-standing planning manager Andrew Fullerton, who was also an experienced architect. This formed the basis for Imperial College becoming lead partner in the W12 Alliance to redevelop and regenerate White City alongside the BBC.

Together with its £3 billion investment, the university has added considerably to its landholding in White City from its original 2009 purchase from the BBC. It now extends over 23 acres. Furthermore, Imperial’s intention for its new West London campus was to provide an innovation ecosystem complete with 3,000 researchers working on pressing scientific challenges.

At the heart of Imperial’s newly-developed campus is a £200 million Research and Translation Centre containing 484,000 square feet of laboratory and office space for academics to work, collaborate and innovate with established technology companies, as well as start-ups. It also contains 198 apartments designed to provide affordable housing for young academics to help drive innovation across the site. In addition, Imperial College’s Advanced Hackspace and Thinkspace brings together over 2,000 like-minded entrepreneurs with the aim of turning their most forward-thinking and inventive ideas into reality.

The other side of the White City triangle and the incentive behind my ‘Smart Value’ concept for the BBC and White City was the retail colossus Westfield, owned by French–Australian consortium Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield. Marking its tenth anniversary at White City in 2018 also coincided with its second phase £600 million extension comprising of an additional 750,000 square feet of new retail space and 1,522 new homes. This also required a £170 million investment in local infrastructure, which benefits the wider neighbourhood. More crucially, Westfield has provided 8,000 new jobs to add to the 12,000 they originally created when the mall opened, with neighbouring residents getting first choice on employment. Westfield estimates that a further £300 million a year will be generated to the local economy through the 2018 expansion.

White City’s regeneration sits at the intersection of commerce and industry in the scientific and medical fields, as well as incorporating a variety of new high-end residential and office developments. This has now attracted other global corporations to this once unmarketable and neglected area of London. In turn, they also offer scale, market power and even financial support to projects in White City. Companies such as Colt, Verizon, Virgin Media, Vodafone, Swiss pharmaceutical leader Novartis and recent addition L’Oréal now have their London corporate bases there. They join aerospace giant Airbus and the UK government’s Defence and Security Accelerator department, responsible for finding inventive solutions to key defence-related challenges in collaboration with Imperial College. Yet the creative arts are also well represented in the regenerated White City, carrying on the BBC’s legacy by adding another vibrant dynamic to the placemaking mix. Among them is the world’s largest online luxury fashion retailer Yoox Net-A-Porter, which opened a 70,000 square foot state-of-the-art tech innovation space in White City Place. Tech Hub is already partnering with Imperial College to offer free coding classes to local children, with an emphasis on boosting digital skills among girls.

The Royal College of Art located its communication, animation, digital art and technology design departments to BBC Media Village, taking advantage of London’s newest research and creative quarter. Another cultural dimension was added when the 1,200-seater Troubadour Theatre opened. This unique ‘pop-up’ theatre is capable of staging full-blown West End/Broadway-scale shows on the site of the BBC’s former car park.

The key lesson behind the successful regeneration of White City is that first, it was beneficial that both BBC and Imperial concurred that their shared aims and visions laid the foundations for subsequent bonds to be forged between academics, scientists, entrepreneurs and corporations, as well as – and just as importantly – its neighbours and the local community.

Second, the productive synthesis of the BBC, Imperial College and Westfield London fortified these bonds in the various amenities available in White City: the restaurants, shops, bars, cafes, gyms, cultural centres and green spaces, while also fostering and supporting a culture of research and innovation on an unprecedented scale in central London.

Sources

1. ‘Being under one roof is an amazing moment for all of us in BBC News, it’ll showcase our strength to the outside world and it’ll create an amazing internal talent pool, so if I’m working on a story, someone who will know that story inside out will be right there, within arms’ reach and I’ll be wanting to make the most of that.’ Mishal Husain, Appendix 3.

2. ‘it wasn’t going to work, I thought things would go wrong endlessly … and it didn’t happen. It was pretty damn near seamless, I must say!’ John Humphrys, Appendix 1.

APM Awards Report (2013) ‘The BBC’s W1 Programme’, p. 4

3. ‘undeniable national interest and one of very few monuments to television history’.

English Heritage Report. ‘“Auntie” honoured in recommendation to list parts of BBC Television Centre’, 2008.

Epigraph

Brady, T. ‘Kevin Roche: “I’m basically a problem-solving construction guy”’, The Irish Times, 2017.