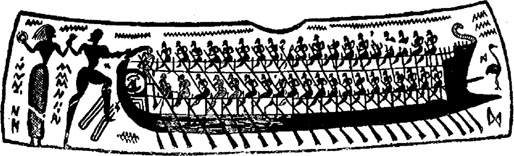

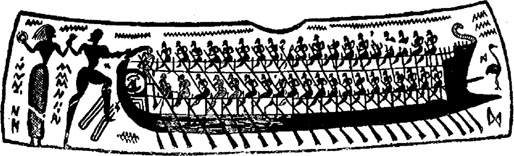

FIG. 7. A PIRATE SHIP. DIPYLON VASE, IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM, (J.H.S., Vol. XIX, Pl. viii.)

OF all the economic facts which from the VIIIth to the Vlth century give the Greek world a new aspect none is so characteristic in its origins or so important in its effects as the colonial movement.

When the ancients relate the foundation of a colony they generally show either the inhabitants of a city compelled to emigrate in a body after an unsuccessful war or a plague, or else a defeated faction forsaking the city of their birth to form in a free land the constitution of their choice. But a movement as general as this, which shifted a great part of the Hellenic race, taking a large population from nearly every Greek land and transporting it to nearly every barbarian country on the Mediterranean, can only have been due to remote, deep-seated, and universal causes. If this phenomenon had been the result chiefly of political troubles it would not have ceased to occur in the Vth century. It is rather with an economic situation as a whole that we must connect it. Even in antiquity certain thoughtful spirits discerned its true causes in over-population and shortage of land. Plato, for example, lays weight on the “narrowness of the soil,” on the “territories which no longer suffice to feed the inhabitants.” We must not, be it said in passing, think of things by the measure of our own day. The excess of population was relative, because the lack of land was largely artificial. If the Greek cities contained so many men without landed property the fault was with the land system. So long as the land had belonged collectively to the gene the man who did not belong to them, or left them, had no other resource but to occupy waste land or to take to brigandage or piracy. After the breakdown of the patriarchal organization the big properties were divided, but still land-owning was prohibited to those who did not belong to the great families or were not descended from men who had taken part in reclaiming the waste, and the splitting up of properties on death created a class of land-owners who could not support themselves. Even more than in Homeric times, Greece fills with adventurers and vagabonds running after every promise of an easier life. If there is a chance of crossing the sea and taking possession of a fertile bit of land, or of making a fortune in any way whatever, they are ready.

Thus the history of Greek colonization presents to us various types of emigrants. Legend places the royal family of the Neleidse at the head of the Greeks who settled in Ionia, and attributes the foundation of Locri to the first hundred families of Locris. A Heraclid of Argos, Tlepolemos, was said to have led the Dorians to Rhodes, and a Heraclid of Corinth created Syracuse. On the other hand Hesiod’s father presents an example of the more ordinary man who is ready to uproot himself. He was descended from a Locrian who had settled at Cyme in iEolis, Not having enough land to keep himself over there, he returned on a small boat to the mother country, and did a little business, until one day he settled in the neighbourhood, in the village of Ascra, where he continued to labour on a barren soil. Among the Parians who occupied Thasos there was a bastard, Archilochos, son of the nobleman Telesicles and the slave Enipo, who, in the course of a life full of ups and downs, had known penury and eased his bitterness in passionate iambics; but the poet had for fellow-emigrants a number of those poor fishermen whom he exhorted to “leave Paros behind, with its figs and its shell-fish.”

What the Greek especially sought in the lands beyond the sea was a bit of land to cultivate. From the days when Homer described the arrival of the Phseacians in Scheria to those in which Athens multiplied, under the name of Clemchies, settlements of colonists, and allotted numerous kleroi in order to increase the number of citizens owning land, the first thing which these emigrants did was to distribute the lands. Archilochos dreams of settling down in the rich plain of the Siris. The Megarians are not drawn to the shores of the Bosphorus either by the easy connexion between the Euxine and the Ægean or by the fish which abound in the bays on the European side; they occupy the Asiatic shore, which alone appears desirable to them with its wide stretches of fertile ground. Love of the soil was for the Greeks the chief stimulus to colonial activity.

But although Hellenic colonization had such a pronounced agrarian character, the acquisition of fields was not its only object, nor were farmers its only pioneers. As a rule, certainly, its prime object was to win land; industrial and commercial prosperity and urban activity were further developments which came when the extension of cultivation was stopped inland by the opposition of the natives, and circumstances became favourable to enterprise on the sea. But it is impossible that the Greeks should not have been led to a certain number of places by the pursuit of movable wealth.

We must not forget that at a very early date, to make up for the shortcomings of the agrarian system, recourse was had to piracy as a convenient method of procuring metals,

FIG. 7. A PIRATE SHIP. DIPYLON VASE, IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM, (J.H.S., Vol. XIX, Pl. viii.)

precious articles, and slaves. But this mode of acquisition had to be adapted to the new conditions imposed on it by money economy and the strengthening of public power. It took the most various forms. In time of war piracy remained almost exactly what it had been, but in time of peace it underwent profound changes.

In the monarchies of the East you could no longer think of taking booty; there was too much risk. Already in the Odyssey Pharaoh’s army teaches the Cretan gangs a disagreeable lesson. Those who were only out for mischief enlisted in the very troops which kept them respectful. The pirate became a mercenary, the brigand turned policeman. With theft: head covered in a helmet, their cuirass rising over the neck, their kilt of straps lined with metal, and their greaves, shield, and spear, the “men of bronze” plied a lucrative trade. They left poor or over-populated regions for the great countries where the kings were rich. They were Cretans, as ever, Parians, Rhodians, Ionians, and above all Carians. Most of them went to Egypt. Towards the middle of the VHth century King Psammetichos took into his service shipwrecked pirates, and sent for a multitude of their fellow countrymen; they all received pay, prizes, and land. Apries was so pleased with these auxiliaries that he collected as many as thirty thousand of them. The Greek mercenaries enjoyed an equally brilliant success with the kings of Asia. A brother of the poet Alcseos went into the service of the king of Babylon. In Lydia Gyges owed his throne to the Carians, and Alyattes, to conquer Caria, raised an army in Ionia. We see what glorious openings the trade of mercenary offered to the descendants of the pirates.

By a development which was also fruitful, but in another way, trade superseded piracy, and was to contribute to the foundation of the colonies. The more peaceable of the bold spirits who ventured to the east were content to do business. The Cretan bandit of the Odyssey already resigned himself to a tradesman’s life. Even in the savage countries commerce, blended with rapine in various proportions, often presided over the birth of the colonies. Even in Homeric times men went to the Sicels to buy or sell slaves. When the Greeks occupy reefs in sight of a much used sea-way, a port on a strait surrounded by mountains, an islet off a big country, or an isolated promontory, it is not in order to follow agricultural pursuits, but to devote themselves to pillage or to unload their goods. The Cnidians and Rhodians who take possession of the Lipari Islands divide themselves into two groups, of which one works the land while the other falls upon Etruscan ships. The founders of Zancle, the future Messina, are pirates. Syracuse has its birth in the little island of Ortygia, and Cyrene in that of Platea, after the manner of the Phoenician “factories.” Most of the settlements created by the Milesians along the Euxine are in their origin only such trading stations, and some of them will never be anything else. When the territory of a Greek colony comprises a fertile plain between two promontories there is nothing to show whether agricultural life there came before or after commercial life. It is quite true that the main object of a Greek colony was only exceptionally trade; but the colonies intended for the settlement of a population were not all exclusively agricultural, even at the beginning. The emigrant who set forth without hope of return was not always looking for land; he was also thinking of trade.

A glance over a map of the Greek colonies is enough to show the kind of service which this maritime empire was to do. Here and there excrescences appear, jutting inland from the coast. These are the agricultural colonies, which have a comparatively large territory. Chalcidice supplies land to the masses driven out of Euboea by the privileges of the Hippobotse. Cyrenaica offers its oases and its pasture-lands to Dorians from every source. In Sicily the Geomori of Syracuse are the lords of over 296,500 acres, which their serfs cultivate. In Italy Locri, Croton, and Sybaris come to occupy all the (Enotrian country to the Tyrrhenian Sea, and grow rich as much by agriculture as by portage across the isthmus. But on the whole the Greek colonies form a fringe, which is almost unbroken. Before Alexander the Great hardly any but the Cypselidae of Corinth and King Battos of Cyrene dreamed of a land empire. The Greeks do not feel easy unless they can see the sea; they are saved once they can shout “Thalassa!” They gather round the Mediterranean like “frogs round a pond.”

In the earliest cases colonization was done at a venture, without pre-conceived plan, by the mere coming together of individuals who were discontented with their lot. At the end of the Mycenaean period Asia Minor had seen a disorderly invasion of bands from all the conquered countries; so too, at the end of the VIIIth century, Sicily and Italy saw an influx, often to the same place, of men of different cities and races. Sybaris was founded by Achseans and by Dorians of Trcezen. Cyrene was occupied first by Peloponnesians and Thessalians and then by Dorians of Thera. The first generations of colonists formed a heterogeneous multitude driven by a common hope of a better condition. Eubœan and Locrian colonization in Italy in particular had this individualistic and almost anarchic character. Nevertheless even in the Odyssey, when the Phseacians leave Hypereia to seek a second home, they are led to Scheria by the godlike Nausithoos, who makes them build the ramparts, temples, and houses and goes on to share out the fields. It is the first example of emigration directed by the public authority. A time comes when it is almost always so. The city, having become stronger, organizes colonization and makes it national. It will no longer allow its sons to be lost to it. The occupation of a country becomes a State undertaking. Everything is laid down by rule. The colonists depart under the orders of a chief, the oikistes, who surrounds himself with priests and soothsayers, and also with land-surveyors. The plan of the new town is designed in advance, and the parcels of ground are drawn by lot. After that colonization is erected into a system. The colonies crowd one on another, and the biggest of them send out a swarm. Rivalry grows up between the cities, especially when the unoccupied districts become scarcer and are further away. Then it becomes necessary that a superior authority should sanction the decisions taken and co-ordinate them in order to avoid conflicts, and that an information bureau should keep up to date a list of reserved areas and vacant land, The Delphic Oracle claims this rôle from the Vlth century onwards, and occasionally performs it.

The Greek colonies, different in their origin, differ still more in their policy towards the natives. Such relations must perforce vary according to the numbers and strength of the colonists, but also according to the numerical force, resources, requirements, military capacity, civilization, and psychology of the populations whose masters or neighbours they have become. In dealing with primitive tribes the Greek, ever versatile, knows how to make himself welcome. He brings the gift which pleases, he finds the word or gesture which charms, he talks over the men, and he makes love to the women; he obtains by a friendly parley the agreement which he wants, the right to open a market or to occupy a strip of land; and the country is his. The Phocseans land on the territory of a Ligurian tribe, the king’s daughter, Gyptis, chooses their leader for husband, and Marseilles is founded. The Theraeans occupy the islet of Platea, work up relations with the Libyans, obtain permission to cross on to the mainland, and behold, the kingdom of Cyrene is made. North of the Euxine Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians receive the Ionian traders well. Once established in a country, the colonists try to expand. Often they employ force, aided by treachery. Syracuse, Leontion, Ambracia, and many other towns are built on territory conquered by arms. The Locrians when they land in Italy conclude a treaty of friendship with the natives and then resort to treachery and drive them away. But you only massacre or expel the natives in cases of necessity; it is better to use kindness and to have your fields tilled by their former owners, whom you have reduced to slavery. The land-owners of Syracuse attach to the soil gangs of Cillicyrians; the Byzantines extort labour from the Bithynians of the neighbourhood; the Heracleiotes force the Mariandynians to till the land and to row in the fleet.

But certain attempts came up against an opposition which could not be broken. There are gaps in the cordon of Greek colonies. Even outside the Eastern monarchies and the area reserved to the Carthaginians and the Etruscans many peoples were able to repel the foreigners. On the shores of the Euxine the Greeks were careful to avoid the parts where the pugnacious Bithynians had succeeded the awful Bebryces of legend. The Messapians and Salentines always prevented Taras from encroaching inland. The Sicels could never be dislodged from the mountains. Sometimes even, when in contact with a highly civilized country, the colonists were influenced by it; the influence of Lydia on the Ionians was very strong, the merchants of Naucratis were Egyptianized, and a great number of Greeks adopted Etruscan fashions.

The advantages which each colony obtained for itself were communicated to the whole of Greece, but first to the mother city. The relations of the colonists with the fellow citizens whom they left behind naturally depended on the circumstances which had determined the emigration. Sometimes they are malcontents or exiles who go abroad to make themselves a better city, like the Lacedæmonians who found Taras and the Locrians who settle in the new Locri. In such a case the rupture is complete. But as a rule the reciprocal feeling is very different. At the moment of departure the kinship of those who stay and those who leave is consecrated for ever by a religious formality. On the altar of the Prytaneion the sacred fire is lighted which will be placed on the hearth of the city to be; the gods of the old country follow their children, to protect them and to remind them of their duty. The colony is bound to show the mother city certain marks of respect and deference. When the colony in her turn sends out colonists, she requests an oikistes of her mother for her daughter. Moreover the colonists are naturally inclined to keep up the customs which they have inherited and to recall dear memories. In intellectual life there is incessant exchange; legend, poetry, philosophy, sciences, and arts unite men’s minds, and currents of ideas cross the seas. It is to the advantage of both that the colony should supply the mother city with cattle or corn and obtain manufactures from her in return. But these bonds, strong though they be, do not in the least weaken the two feelings which are inborn in the heart of the Greek, a love of liberty and a passion for his own interest. Independent cities are added to the number which is already so great, and new countries offer old Greece, in their laws and their manners, admirable schools of practical individualism.

There is perhaps not one Greek colony whose history would not add some feature to the picture of the activity which ferments in Greece for more than two centuries. But it will suffice to take them in large groups, in order to remark what is most characteristic in them.

Thrace was bound to attract the dwellers by the Ægean with its corn-fields and vineyards, its forest-clad mountains, and its mines of gold and silver. Opposite Euboea there was a peninsula with a fertile soil and a wonderfully indented coastline. Its three promontories seemed to beckon to the neighbouring island. Chalcis responded to the call; she needed land for her peasants, wood for her ship-builders and markets for her metal-workers. At the end of the VIIIth century Chalcidice contained thirty-two towns. One of them, Potidaea, which stood on an isthmus, was naturally a creation of the Corinthians. Almost immediately the Parians rushed to Thasos, rich in gold, and from Thasos on to the mainland close by. The cities of Ionia and iEolis wanted their share, and the Chians settled at Maroneia, the Clazomenians at Abdera, and the Mytilenaeans at Ænos.

The Greeks of Asia already overlooked the great route to the Euxine. It was a domain which they reserved for themselves, iEolian Lesbos took up position on the two shores of the entrance. She was followed by Miletos, which went on and on, from harbour to harbour, and by her example drew after her Phocsea, Teos, Colophon, and Samos; the Propontis became an Ionian lake. Then Megara appeared on the scene, and founded Chalcedon, and then Byzantion; the Bosphorus was hers. Now the Greeks saw lying open before them a vast sea whose storms, fogs, and frosts they regarded with dread. On the other side, according to vague rumours, there lived hideous and cruel peoples. For a long time they stayed there, before the “inhospitable” sea, not daring to brave it. But gradually stories went about of lands where wealth lay in heaps and the Golden Fleece was hidden. The Milesians took the risk. Their daring made the sea “hospitable” and won the treasures of the Euxine. On the southern shore, from Sinope to Trapezus and Phasis, they found timber, fruit, iron, and the trade-routes of Asia. On the northern coast, which offered them an inexhaustible store of grain and fish, they settled at Olbia, Panticapseon, and every point favourable to trade and fishing.

While the Greeks did not occupy any territory in the great countries of the East they did not abstain from exploiting them. They had to leave relations with Assyria, Media, and Persia to the Phoenicians, and even in Cyprus Hellenization made very slow progress. But, at the ends of the continental monarchy of which Phoenicia was the sea front, two phil-Hellenic countries were like colonies to them. In Lydia the Mermnadae received them kindly for a century and a half (687-546). In Egypt traders were as well received as mercenaries and were able to establish permanent “factories.” There too the Milesians set the example and secured the best share. About 650 they entered the Bolbitine Mouth with thirty ships, and they built a fortified trading station, the “Milesians’ Wall.” A little later they founded Naucratis on the Canopic Mouth and Daphnse near the isthmus. They obtained the right to penetrate to the interior; they had their own quarters, or at least bazaars, in Memphis and Abydos. In the wake of the Milesians traders came pouring in everywhere. When Amasis ascended the throne (569) the Greeks might hope for everything. The monarch went out of his way to please them. He allowed the Samians to trade in the Great Oasis. Then he took a step of capital importance; he concentrated the Greeks of Egypt in Naucratis. Thus there was in the Delta a city administered in the Greek fashion, with its “nations” grouped round a sanctuary and an emporium. Special temples and quays were reserved for the Milesians, who enjoyed undisputed pre-eminence, the Samians, and the Æginetans. Nine other cities shared the Hellenion. Naucratis very soon became the chief market in Egypt, and one of the chief markets in the Greek world. The prototype of the future Alexandria, it accomplished down to the Persian conquest a remarkable work of Hellenization.

In Cyrenaica, again, conditions were favourable to colonization. From the earliest times the Greeks had known this coast of Libya; the north wind drove their ships there when they wanted tc> go to Egypt. Cyrene, founded by the Peloponnesians and Thessalians, did not attain its full importance until it had received a new influx of immigrants. Then it became the thriving capital of an African Greece.

While the cities of Asia Minor and the isles had almost a monopoly of colonization in the eastern Mediterranean, Greece proper took a leading part in the colonies of the west. Everything drew the Greeks to Italy and Sicily—an almost virgin soil, forests near the sea, and a convenient voyage which, after a crossing of forty nautical miles, simply followed the coast. Even in the Mycenaean age the Messapians and Sicels bartered hides and slaves for vases and arms from the east. In the Homeric period strangers appeared more often as pirates than as merchants, and the natives had to take refuge in the first lines of hills in order to receive pottery with Geometric pattern. Soon the pillagers found the country to their liking. The Euboeans of Chalcis were the first to found colonies in the west, as in Thrace. They first settled in Sicily, from Catane to the Straits, the two shores of which they commanded from Zancle and Rhegion. At once they sent out their ships into the Tyrrhenian Sea and founded Cumae.

Peoples better situated and greedy for land followed in their footsteps. The Achseans, and then their neighbours the Western Locrians and the Laconians, poured the surplus of their agricultural population on the shores of Basilicate and Calabria. There anchorages are very rare but land is fertile. Towns arose, and soon shaped a brilliant destiny for themselves. Taras had the advantage of possessing the one good harbour on the gulf. Croton, Sybaris, and Locri expanded at the expense of tribes which were ready to be Hellenized or resigned to serfdom. Between the Ionian Sea and the Tyrrhenian they organized the transit of Ionian and Etruscan goods. Thus they were at the head of small empires. The wealth and power of these cities made a deep i pression. It was said that Sybaris, with its 300,000 inhabitants, ruled oyer twenty-five cities and four native peoples. The enormous quantity of the objects heaped in the ruins of Locri indeed suggests a considerable town.

The commercial cities of the Isthmus, Corinth and Megara, situated between the Chalcidians and the peoples of the Ionian Sea, could not renounce all interest in the West, and once the Dorians of the mainland had taken the road those of the islands, Rhodians and Cretans, refused to be left behind. Corinth took a strong position on the island at the starting-point of the sea-routes to Italy and to the Adriatic countries, Corcyra. All along iEtolia, Acarnania, Epeiros, and Illyria the sailors of the mother city and those of the colony took possession of the alluvial plains and the native markets. But already the Corinthians had been to reconnoitre the safest and widest harbour in Sicily; they founded Syracuse, which was soon mistress of an extensive territory, many slaves, and boundless wealth. The Megarians installed themselves in a new Megara; the Rhodians, uniting with the Cretans, founded Gela. It was then that the Sicilian cities began to send out swarms of their own, one after another. The Megarians, cramped for room, made for Selinus, the people of Gela for Acragas, and those of Zancle for Himera. East, north, and south, the whole Sicilian seaboard belonged to the Greeks.

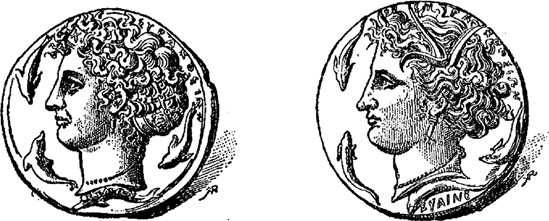

With their cities crowded one on another Italy and Sicily were an extension of Greece proper. But in these countries everything happened on a bigger scale, with greater freedom of movement, less respect for tradition, more practical intelligence, and also more inclination to bluff. In the West Greece found its Americas. The well watered valleys yielded grain in masses while the highlands fed countless herds. The export of corn, live-stock, hides, and wool counterbalanced the import of manufactured goods and artistic objects. An active transit business carried textiles, vases, and metals to and fro between the Greek seas and the Etruscan. Sybaris and Syracuse were far bigger than any town in the old country, with streets and avenues at right angles stretching over the plain, and these crowded cities, rolling in money, called on the architects to produce monuments which should be the “biggest in creation.” The art which in Sicily was the most original in character and the most perfect was that which is most typical of a mercantile society, the engraving of coins. Even philosophy, transplanted into the West, took on a local flavour; it became practical, in the form of political theory, rhetoric, or applied science, with a pronounced tendency to advertisement and ostentation.

Beyond the Tyrrhenian Sea lay the fabulous lands of Liguria and Hesperia, the “Far West.” From there the

FIG. 8. COINS OF SYRACUSE, SIGNED CIMON AND EUæNETOS. (D.A., Figs. 5120-1.)

precious metals came. But from Cumae and Cyrene to the Pillars of Heracles the whole seaboard was reserved territory, for the Etruscan and Phoenician navigators allowed no others to visit the Ligurian tribes, the Iberian empire, or the kingdom of Tartessos. At length circumstances became favourable for the entry of new rivals on the scene; Tyre was ruined and Carthage was no longer at the zenith of her greatness. The Greeks seized the opportunity. About 630 a merchant of Samos, Colseos, was driven by storms to Tartessos; he came back with a cargo, the sale of which brought in sixty talents. The Greeks now knew where to look for the land of silver, and knew, too, that it had a friendly population and a generous king. The sailors of Ionia and Rhodes crossed the Sardinian Sea. The most fortunate were the Phocseans. Living on fishing, trade, and piracy, they roamed about in their fifty-oar ships, the penteconters, slender, swift, and armed for war. As clever as they were bold, they so pleased the king of Tartessos that they obtained from him all the gold needed to build for their city a circuit of ramparts. After hovering about the coasts of Iberia and Liguria, about the year 600 they fixed their choice on a roadstead near the Rhone, perfectly safe and ending in an excellent harbour at the mouth of a fertile valley; there they built Massalia (Marseilles). The Massaliots, aided by the Phocaeans, swarmed in their turn. In the west they founded Theline the fertile Pap (Arles), Agathe of Good Fortune (Agde), Pyrene (Port-Vendres), the new Rhodes (Rosas), the market of Emporion (Ampurias), Hemeroscopion or the Day Look-Out, and Maenace (Malaga) near the “springs of silver.” To the east they occupied Olbia, Antipolis (Antibes), Nicgea (Nice), and Monoecos (Monaco). Greek money went far, and from far the products of the mines came pouring into the Greek ports. In the west a Phocsean thalassocracy menaced the peoples who had hitherto ruled there. About 560 it invaded Cyrnos (Corsica); from Alalia it overlooked the Italian coast. Twenty years later, when the King of Persia had subdued Ionia, the people of Phocsea emigrated in a body and made Alalia into a great city.

After two centuries of uninterrupted progress Greek colonization was bound to provoke a general reaction. In the east the land monarchy of the Persians took from the Greeks the markets of Lydia and Egypt, set up a barrier to their enterprises in the Scythian country, and annexed Ionia itself; the Phoenicians were avenged. In the west the Etruscans, combining with the Carthaginians, compelled the Phocaeans to evacuate Corsica and to recognize Cape Artemision (De la Nao) as the limit of their zone in Iberia. The Persian Wars were extended over the whole Mediterranean. But Hellenism, attacked on all sides, revealed its strength; Salamis and Platsea had their pendants in Himera and Cumse. Greater Greece was saved.

From the Caucasus to the Pyrenees the Greeks maintained on relatively large territories and in towns with a dense and composite population those innumerable types of autonomous, original cities in which everything favoured social experiment and political progress. From the posts where they had stationed themselves they continued to radiate their civilization over all the surrounding countries. They no longer had to fear stifling for want of room or dying of starvation; for they possessed all the land they needed, they could provision themselves with corn from the most productive countries, Scythia, Egypt, and Sicily, and, lastly, they held the markets in which the wealth of the whole world was concentrated.