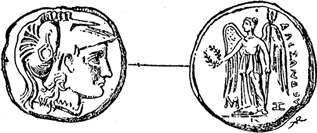

FIG. 48.

GOLD STATER OF ALEXANDER. (D.A., Fig. 215.)

AS a result of the conquests of Alexander enormous quantities of precious metal were thrown on the Greek market, and in addition this market was extended to vast countries in which natural economy had hitherto prevailed. In consequence a circulation of money of unprecedented intensity quickly affected the economy of countries which had hitherto not felt the need of money. After a sudden upset of the equilibrium in the price of commodities the abundance of specie was corrected by a vaster output of goods coming on to the market, and at length a new equilibrium was established.

Even in the course of the IVth century masses of gold had been put into circulation all over Greece. But what were the 10,000 talents seized from Delphi, and the 1,000 talents which King Philip #took annually from Mount Pangseos, in comparison with the treasures which Alexander found in the palaces of Persepolis, Susa, Ecbatana, and Babylon? There, in bullion piled up for two centuries, lay enough to stagger the imagination; it was reckoned at a value of 170,000 talents (£40,000,000). All this was put into circulation with incredible speed. The extravagances of a young and luxury-loving king, his gifts to members of his family, his rewards to common soldiers and generals alike, the offerings which he sent to the temples, and the sums which he expended on buying political help would very soon have dispersed the reserves of the Achsemenids.

The monetary system which Athens had given to Greece was transformed. For some time the abundance of gold had reduced the ratio of the yellow to the white metal to 1: 10. The gold “Philips,” weighing the same as darics, had for subsidiary money silver currencies which conformed to this ratio and were able to compete with the owls of Laureion; Darius’s bi-metallism had been modernized. Alexander made the system agree with the Attic standard. He thus refrained from damaging the Athenian tetradrachm, which continued to be accepted on the market and was even given a pan-Hellenic value at the beginning of the 1st century by an Amphictionic decree. But the gold “Alexandrines” none the less had a universal success, surpassing that of the Philips. Their name was preserved for a long time. They were imitated as far as Gaul, and cities of the Euxine which had

FIG. 48.

GOLD STATER OF ALEXANDER. (D.A., Fig. 215.)

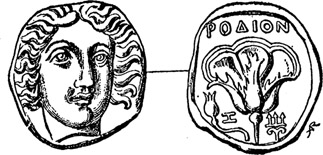

never belonged to the Macedonian were striking silver coins with the head of Alexander a hundred and fifty years after his death. On the other hand, the Æginetan silver standard, issued by Rhodes, took its revenge on the Attic standard and spread to Egypt, Sicily, and even Carthage.

At first the greatest sums went to Europe. The Greek allies, dismissed after the conquest, took with them, in addition to what they had saved on their high pay, 2,000 talents

FIG. 49.

DIDRACHM OF RHODES. (D.A., Fig. 2569.)

in bonuses. When Harpalos came to bribe the Athenians he had 700 talents in his cash-box. The governor Menes had 3,000 talents at his disposal with which to fight Agis. Queen Olympias sent darics to Delphi, and the naopoioi there often did their accounts in darics. Indirectly, the Oriental magnificence of the court enriched the artists, merchants, and manufacturers of the more refined towns. A flood of gold poured over Greece.

But the countries of production on a large scale were soon to have their share. Being obliged to obtain its farm produce and raw materials abroad, Greece could not go on indefinitely draining the treasures put into circulation, nor even keep all the wealth which it had attracted thanks to exceptional circumstances. The Greek peoples were now mixing with other peoples whose material life had been very different. Among these latter some were to remain faithful to their tradition of natural economy, while the others, being ready to give the surplus of their enormous production, and having nothing to demand in exchange but money, moved steadily towards money economy.

To the former class most of the provinces ruled by the Seleucids seem to have belonged. Despite the proximity of the Phoenician coast, despite the obstinate efforts of the ruling house to extend the city system, the countrysides of Asia did not cease to pay their taxes in corn, and, except in the big towns, the royal treasuries were storehouses. Epeiros presented a more curious spectacle. Right in the Illrd century, when Pyrrhos set forth to conquer the world, this mountain land was still at the most primitive stage of natural economy, the pastoral. Large and small cattle, such was the chief wealth of the king and nobles. The general supervision of the royal flocks and herds was one of the highest dignities in the State; the Herdsman-in-chief was one of the officials of the Court; to reward the zeal of a subject, the king would give him a yoke of oxen. Countries which exported little lived on their home-grown resources and hardly used the instrument of universal exchange.

Very different was the situation which gradually arose in Ptolemaic Egypt. The ancient valley of the Nile, where men seemed petrified in the institutions of centuries, like the statues in their hieratic attitudes, and so many generations had lived on the year’s harvest without their thoughts going further, stirred and woke to a new life. The kings of Persia had taught Egypt the value of money when, they demanded of her as tribute, in addition to the 120,000 measures of corn which cost her almost nothing, a sum of 700 talents. But, if she then converted corn into precious metal, she only procured just the amount which she must send to Susa. When the Macedonians and Greeks became masters of the land, they saw all that was to be got from the inexhaustible fertility of the soil and the admirable position of the coasts. In making themselves rich they enriched the conquered people. Even before Alexander had completed the subjection of Asia, the governor whom he had left in Memphis profited by a general famine in a masterly way. He bought up all the corn in Egypt, and, having the market in his hand, diverted to himself some of the stream of gold which was flowing from Persia into Greece. The Ptolemies exploited their kingdom systematically, in their own interest and that of the country. For the first time the need of a national currency in precious metal was felt; hitherto a few clumsy copper pieces had sufficed. After the Attic and Rhodian systems had been tried, the preference was given to the Phoenician system, because it best permitted the harmonizing of the Greek standards with the copper weights hitherto current. The ratio of silver to copper was fixed at 1: 120. It is true that copper was always most widely used. Considerable sums in copper were handled. Silver was at a premium. In the Illrd century the official documents allowed, for payments owed in silver and effected in copper, an exchange fee of 10%. In the Ilnd century silver became still scarcer; debts and even fines were paid almost entirely in copper. The result was a depreciation of copper, which grew worse until the end of the dynasty. The ratio of the two metals rose to 1: 240, then to 1: 375, and even to 1: 500. It is none the less true that the Ptolemies greatly furthered money economy in Egypt.

And indeed we see, in every manifestation of public and private life, natural economy steadily ebbing. This does not mean that, even in three centuries, Egypt recovered all the advantage which Greece had over her. Egypt always did far more exchange in kind than Greece. Sometimes, it is true, in the cities of Asia Minor or in the isles, land-rent was still paid to the temples partly in grain, wood, or cattle, and the sacred administration of Delos supplied two workmen with corn and clothing for two years, and paid only their opsonion in coin, but these were survivals or exceptional cases, which cannot be taken as typical of the economic system. In Egypt, On the other hand, native society was still everywhere wrapped up in ancient custom. In almost every village we find, opposite each other, the public bank, into which the money went, and the public granary, into which the harvest went. In both establishments the same operations were carried on. One accepted the deposits and effected the payments of craftsmen and traders, and the other was the centre of business for the farmers. The economic development of Egypt is expressed by the fact that the business of the granary declined in favour of the bank.

The State did not wish the peasant to be placed at the mercy of the retailer and the usurer by the need for procuring coin. It accepted the payment of the land-tax in kind, when the tax-payer brought commodities which were easily preserved and were used by the State, corn and oleaginous seeds. With the wheat and barley it maintained the soldiers and officials, selling the surplus and thus reducing the proportion of wealth in kind in its receipts. Croton and sesame served as raw materials in the royal oil-mills. But all other taxes, even the duty on vineyards, palm-groves, and olive orchards, were paid in money. Of all its revenues the treasury collected only one thirtieth in kind. For the royal domain, as for the temple lands, the leases stated the rent in natural values. The tenant owed so much corn per aroura. The relative value of products was fixed by a scale, just as that of minted metal was fixed by the monetary system. Wheat was equal to lentils; it was to barley as 5 to 3; and to durra as 5 to 2. But provision was also made for conversion into money; it must be done according to the rate. And the priesthood encouraged this more and more, for it was always wanting more capital for its commercial dealings.

As receipts in kind diminished, the expenses which they covered necessarily became more limited. The State paid officials from its granaries or from its banks. The minor staff received food-stuffs. The high dignitaries were allotted mixed emoluments; the scholars of the Museum were boarded and lodged, and drew a salary. Sometimes even salaries which were fixed in money were paid in kind. But the history of army pay well shows the economic development. From the Illrd century onward the original pay, called sitarchia because it once consisted of corn, was issued in coin; to designate the supplement issued in kind a new word was needed, sitometria, in distinction from the old. In its turn the sitometria tended to undergo the same change. In the Illrd century a soldier got 150 drachmas of copper and 3 artabai (3J bushels) of corn; in the Ilnd century only one of these three artabai was supplied in kind, and the conversion of the rest into coin brought the amount of money paid to 350 drachmas, representing three quarters of the total pay. The foot-soldier who was entitled to wine and the cavalryman who was entitled to his horses’s forage drew an allowance. The purveyors to the State were paid in coin alone.

In the private life of the Egyptian villagers natural economy survived in part. They continually borrowed corn or wine. But if a debtor did not pay up when the debt fell due it was converted into its money value at the rate of the day. This conversion, which was at first favourable to the creditor and was enforced by a penal clause, was soon to have a beneficent influence; for it was admitted that in the case of obligations in money the compound interest could not make the debt exceed double the principal. In workmen’s wages, as in army pay, the part paid in kind decreased. We find a carter who receives, for himself and his men, daily rations of bread, wine, and oil, with a small pig on holidays, without counting the hay for his beasts. But we also find a gang of quarrymen who get, in addition to an artabe of corn and a small measure of oil, 12 drachmas in money; the proportion of the cash is 83%. The priests, who used, in their byssos-works, to leave a part of the output to the workmen, came gradually to adopt a more modern method of payment. Soon labour was not paid in foodstuffs at all. Navvies got one tetradrachm per cube of sixty naubia. By now, in Egypt as elsewhere, the name opsonion given to wages had no longer any reference to reality. In short, money became necessary everywhere. Every fellah needed it. The papyri show us housekeeping accounts in which the expenses of the very humblest houses are noted down day by day. Everything is bought; those who have their corn pay the baker in drachmas; even the beggar gets his coin. Money, or rather copper, was not only the most convenient standard of value, but the instrument of exchange used in the most remote villages.

The changes brought about by the progress of money economy in the distribution of the precious metals and of commodities led to marked variations in prices. When, after Alexander’s conquest, Greece received the rain of gold which the east wind brought, it was not much the richer, nor did it remain so for long. The total amount of products was not increased; indeed a succession of bad harvests diminished it. A rise in prices was inevitable, and its rapidity was fantastic. But, thanks to the expansion of the market, the amount of commodities put into circulation soon began to counterbalance that of the precious metals. It weighed heavily on prices. From the end of the IVth century to the middle of the Illrd, a strong and steady fall almost corrected the enormous rise of the years 330-320, and restored the balance of values on a greatly enlarged market. Once the countries of high production and those which held the precious metal had made the necessary exchanges, and monetary economy had thus come into force everywhere, about the middle of the Illrd century, the fall, being no longer needed to unify and clear the market, ceased spontaneously. Things resumed their natural course. Until the Roman conquest, prices once again were steady or rose by slow, healthy movements.