1

William Morris: Decoration and Materialism

From the late 1870s William Morris delivered lectures on art and society, and published articles on the subject, seeking to promote a new vision of art that would rescue it from the position to which it had been relegated by modern social conditions. His involvement in liberal anti-war politics in the period 1876–78 and his subsequent involvement in socialist politics in the 1880s and beyond led him to articulate a politicised art theory that ought to be recognised as the first English-language attempt to produce a Marxist theory of art. The debate over whether Morris’s Marxist politics were compatible with his art practice (producing handcrafted luxury goods for bourgeois consumers) is a tired one and I do not intend to repeat the standard terms of the debate, which is one with which Morris himself was wearily, if anxiously, familiar. Walter Crane’s comment on the fact that Morris produced ‘costly things for the rich’ while campaigning for socialism puts the issue starkly in terms of the alternative, within a capitalist era, of making cheap goods for the common people. He explained Morris’s view that

according to the quality of the production must be its cost; and that the cheapness of the cheapest things of modern manufacture is generally at the cost of the cheapening of modern labour and life, which is a costly kind of cheapness after all.1

The questions that this chapter seeks to address are: ‘How did Morris’s politics shape his understanding of the nature of art?’ and ‘What currents of thought were available to Morris to help him develop his aesthetic theory?’ I suggest that, although he was working in the absence of an established repertoire of Marxist writings on art, cultural debates in the latter part of the nineteenth century foregrounded the question of development and degeneration. The terms of these debates and the polarisation of positions that emerged played a part in the way he understood art. It is well established that Morris’s concern over the state of modern art and craft production, his efforts to put modern art into a historical perspective and his efforts to lay out the prospects for art derived in part from John Ruskin’s example. Ruskin in his early works, such as Modern Painters (1843–60) and The Stones of Venice (1851–53) laid the groundwork for Morris’s view of the pitiable state of modern art and craft in comparison to the flourishing, expressive and idiosyncratic work of medieval producers. Ruskin insisted on two central suppositions: that the artistic standards of an age are an index of the religious and ethical values of that age and that they were shaped by the conditions under which artistic labour was undertaken. Modern art and architecture were seen to be lacking; the remedy was to address the values of the age and the social organisation of labour. Morris adopted and adapted these tenets to produce a body of theory very different in its political complexion from the often conservative or reactionary work of Ruskin. This chapter aims to add some other reference points, not as documented sources for Morris’s thought but as intellectual resources, some of which he could have accessed, directly or indirectly, to contribute to his formulations about the link between art and society, and the question of the development and/or decline of art.

In a memoir, George Bernard Shaw recalls that Morris became friendly with him following Shaw’s denunciation of the book by Max Simon Nordau, Degeneration (1892).2 Nordau was a physician who had moved into journalism and had emerged as a prominent social critic. Morris read the English translation which appeared in 1895 and expressed disgust at the following attracted by the book. Nordau, drawing on Cesare Lombroso’s sociological writings, characterised the cultural products of the modern age as degenerate.3 The whole culture was displaying pathological symptoms, he argued, ‘a sort of black death of degeneration and hysteria’ which involved ‘weakness of the higher cerebral centres’, failings in the functioning of sense perception and excessive preoccupation with licentious ideas. Altogether these indicated a sickness in society at large comparable to the effects in an individual of an exhausted nervous system.4 Morris was attacked by name, along with Ruskin and the English Pre-Raphaelites, who were said to display the mystical tendency (as were Baudelaire, Verlaine, Tolstoy and Wagner). The recurrent faults, ‘vague and incoherent thought, the tyranny of the association of ideas, the presence of obsessions, erotic excitability and religious enthusiasm’, were thought to mark out these artists as degenerates as surely as the earlobes or cranium, or the give-away tattoos, of a criminal, prostitute, anarchist or lunatic.5 Their ‘anthropological family’ was, Nordau claimed, akin to that of the atavistic social deviants documented by Lombroso. These artists, who were effectively modern savages, were spreading the plague of aesthetic debauchery: ‘every one of their qualities is atavistic’, ‘they confound all the arts, and lead them back to the primitive forms they had before evolution differentiated them’.6 Nordau, like Ruskin, was concerned with the link between art and society, and the question of aesthetic retrogression. He drew on right-wing anthropology and psychiatry to stigmatise the advanced practitioners in European art, music and literature and to drum up a sense of cultural crisis, calling for purity committees to undertake vigilante action and for the medical and psychiatric profession to publish denunciations of public figures. It is not surprising that the venerable Morris was disgusted, not least because Nordau’s broad-brush cultural critique was hailed by some as powerful and vested in a principled socialism. The Daily Chronicle, for instance, reviewing another translated work by Nordau with Degeneration, said ‘the book is a fervid revolutionary protest in which much powerful political, economic, and social criticism is blended with the declamatory rhetoric, the Secularism and Socialist platforms.’7 Nordau was particularly poisonous because he adopted some of the assumptions and strategies on which Ruskin and even Morris depended. The tradition of allying social criticism to aesthetic judgement, the summary presentation of large sweeps of history and the rhetorical move of evoking a future in which current conditions had worsened disastrously were to be found in Ruskin and Morris. In this chapter I will be suggesting, in addition, that anthropology, the resource of Nordau, was a relevant reference point for Morris’s writings on art too, though not the right-wing anthropology of Lombroso. It was possible for Morris to give a positive value to ‘primitive’ people, to understand artistic impulses as existing in ‘primitive’ society and even to take on something of the identity of ‘the savage’.

Even outside the scholarly books and journals of the anthropologists it is clear that the idea of a modern primitive sensibility had some currency as a positive quality. Andrew Lang in his essay of 1886 for a general middle-class readership, ‘Realism and Romance’, suggested that civilisation is laid on over a savage interior, and consequently mankind would still thrill to the wildness of adventure and the marvels of romance despite the effects of the rational side of modern existence. Lang was a friend of Morris and we can assume that Morris was familiar with his ideas. He was arguing for the value of a rousing story such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped as superior in some ways to the grim realism and intellectual rigour of a work by Dostoyevsky.8 He imagined a future man who has lost the hair and nails that modern man possesses as heritage of his wild past, but stated that, for the present, there is a taste for those tales that ‘may be “savage survivals”’ telling of battles and monsters. ‘Not for nothing did Nature leave us all savages under our white skins: she has wrought thus that we might have many delights, among others “the joy of adventurous living” and of reading about adventurous living’. The white skin may be, he is arguing, a sign of our advanced civilisation, our increased civility and urbane manners, but what about the savage self that survives under the surface, under the skin, or in the extruding hair and nails? Lang the poet, classicist, collector of fairy tales and writer on folklore and totemism is surely referring with the phrase ‘savage survivals’ to Edward Tylor, who was well known for his arguments about savage survivals in Primitive Culture (1871). Tylor set out to refute the idea that inhabitants of primitive cultures were devoid of intelligence and lacked any religious sense, and above all he wished to challenge the idea that existing ‘primitive’ peoples are to be understood as having degenerated from a former state of higher culture. Degeneration could occur in pockets but overall the history of humankind showed a continuity and a progress, he thought.9 According to Tylor modern culture in games, certain kinds of ritual, and superstitions contained survivals of an early sense of religion. These survivals were used by him as evidence for the continuing existence of a religious sense which could be traced back to earliest society where belief in spiritual beings or, as he termed it, animism coexisted with a practical rationality and problem solving, a ‘rude, shrewd sense taking up the facts of common life’.10 The one constant feature of human society from its dawn to modern times was a belief in spiritual entities. The greatest rupture was not between savage and civilised man, but that occurring in modern times between those who acknowledged the existence of divine being and those materialists who denied the existence of God.11 Tylor then, with his model of development rather than degeneration, envisaged an affinity between modern people and primitive people. The liberal implications of this formulation made it a version of the savage-in-the-modern which stood at the opposite extreme from that account of the degenerate modern savage given by Nordau.

Late nineteenth-century investigations of folklore and non-European culture and debates about the vigorous or exhausted condition of modern western society were subtended by the involvement of the European powers in imperialist adventures.12 When Morris came to read Nordau’s Degeneration in 1895 or 1896, in the last year of his life, he had been active in left-wing politics for well over a decade; 1883 was the year in which he had read Marx’s Capital. As has often been recounted (most vividly by E. P. Thompson)13 he was drawn into politics through the anti-war movement of 1876–78, when the Conservative government’s foreign policy, in support of Turkish involvement in Bulgaria, became the focus of agitation. It is significant that his path into politics was marked by opposition to imperialism and that he maintained a robust opposition to imperialism in his writings until the end of his life. This in turn inflected his formulation of a politicised aesthetic. As his political views developed he became alive to the limitations of Gladstone’s bourgeois liberalism and moved towards the explicit class politics of Hyndman’s Democratic Federation, which he joined in January 1883. For the rest of his life he involved himself in the day-to-day work of the revolutionary socialist movement, maintaining a position against the parliamentary road proposed by Hyndman and Aveling and later, in 1890, against the anarchist politics of Lane, Kitz and Mowbray.14

Morris in his art theory encouraged the practice of handcraft with its possibilities for individual expressiveness. He allowed for a temperate use of the machine to reduce labour, but with the proviso that in a capitalist mode of production the machine was inevitably annexed to the drive for profit and the inequitable class system. The extraction of surplus value had made it impossible for machines to be used rationally for the abatement of toil. His scathing comments on the tag ‘labour-saving’ as a description of machines in modern capitalist enterprises (when they were just saving wages and boosting output) and his positive regard for handcrafted goods might lead one to assume that he was hostile to the machine per se, but a close reading of his comments shows that this is not the case.15 He could conceive of the benefits of the use of machines. The worker would have to decide. The decision to compromise, and sacrifice the verve and pleasing quirkiness of hand finish for the speed and convenience of machine production, might indeed be reasonable, he argued, but that compromise could only really be assessed and accepted in some other (future) era, in which the machine and the worker were freed from the exigencies of accumulating profit and the worker existed in social equality with his or her fellows.16 It is clear then that Morris’s art theory after 1883 only really concerns the role of art in socialist society; he can merely consider its adumbration in the capitalist era. As such, art is the locus of hope for the future and simultaneously the vehicle of regret for what is impossible in the present. It is entirely characteristic of Morris that the hope and the regret should be twinned in this manner. So he found handwork commendable but could not exactly be said to advocate a return to handcraft (and here the distance from his mentor John Ruskin is crucial). Handwork should allow the worker to take pride and pleasure in producing something, whether plain or ornamental – and will do so in a communist era.17 Indeed it will allow all workers to participate in the making of art and to realise most fully the human potential for aesthetic activity. Ornament would then arise from the fact of unalienated labour, where the pleasure and satisfaction that existed already in making a utilitarian object were simply amplified by the beautifying of it, in conditions where sheer need did not preclude the spending of additional time on the object. Morris considered that art serves two purposes: the enhancement of leisure in the contemplation of art and the channelling of energies in pleasurable work. In capitalism it cannot truly fulfil either purpose and yet there is an assumption in Morris that is of central importance for the case argued in this chapter, that the taking of pleasure in art is a constant factor in human society, only forfeited under the most extreme conditions.

As he contemplated the slide of the world into intensified misery, that bleak alternative to the victory of the working class and the founding of a socialist society, Morris imagined the extinction of hope, the degradation of the working class pursued to such an extent that overwork, dirt, ignorance and brutality came to have total sway. The loss of hope would be the extinction of the feeling for art in the working class; art then is an index of the revolutionary potential of the proletariat. Its extinction in the defeat of the working class would be mirrored by the inability of the ruling class to experience or foster aesthetic pleasure. He imagined the burdening of the world with hideous high-tech structures driven by a perverse science. He imagined as the only outcome ‘some terrible cataclysm’ and a revisiting of the primitive struggle with nature for survival. I should point out that there is always a degree of ambivalence in Morris’s account of the functioning/malfunctioning of art in capitalist society. This dystopian vision is here offered as a horrible alternate future. At times though, it stands, in his accounts, as the wretched state of existence at the present. He pushed the dystopian vision further. The visiting of ‘some terrible cataclysm’ would at least be a deliverance from the unhealth and injustice and despair of class society where the ruling class has definitive unchallenged sway.18 The benefit would be the eventual revival of an inherent feeling for art in a reprise of human development.

Man may, after some terrible cataclysm, learn to strive towards a healthy animalism, may grow from a tolerable animal into a savage, from a savage into a barbarian, and so on; and some thousands of years hence he may be beginning once more those arts which we have now lost, and be carving interlacements like the New Zealanders, or scratching forms of animals on their cleaned blade-bones, like the pre-historic men of the drift.19

The anthropological reference is telling. Morris indicated repeatedly that he considered the love of art and the capacity for making art to be inherent human characteristics. They could be expunged in dire circumstances but the evidence of history and anthropology indicated that they were omnipresent in human society. He points out that there are no human societies that have left any trace in which art making was not a feature (effectively this is to define the human as a social rather than a biological entity). Morris locates the source of art as interior, in human make-up – ‘I believe the springs of art in the human mind to be deathless.’20 – and considers the ornamental spirals of Maori decoration to arise from the same source and serve the same purpose as the interlacings of his own tapestry designs. He identifies a part-physiological, part-psychological need that art satisfies, not expressed as the craving for pleasure but rather as the pressure of restless energy that needs to be soothed by art and needs to be vented in the making of art.21 Notably this formulation does not conceive of the mind as disembodied, operating in a disengaged realm of pure rationality, but as embodied; it is this that makes his remarks curiously akin to Freud’s account of artistic activity as sublimated energy. To this is added the constant emphasis on the embodied artist engaging in the physical process of making: swinging a hammer, or wielding a shuttle or carving tool. In Morris’s view the making of art is not generically different from any kind of satisfying, productive manual operation. The fact that Morris could identify in this way with the producers of functional objects, in societies considered savage or primitive, involved a significant leap of the imagination.22 The terms in which he connected his own experience with those of distant cultures are not those of Tylor, but clearly Morris would have found Tylor’s work more enabling than Nordau’s. His connection with ‘the primitive man of the most remote Stone Age’23 was made on the basis that there existed universally in humankind an aesthetic impulse.

Lang spoke of the moderns being savages under their white skins, but Morris underwent an adaptation of his skin colour. Walter Crane told an anecdote concerning Morris in which visitors to the Merton Abbey Works were looking for Morris when they heard his loud and inexplicably cheery voice crying from a back room ‘I’m dying, I’m dying, I’m dying!’ All became clear when: ‘The well known and robust figure of the craftsman presently appeared in his blue shirt sleeves, his hands stained blue from the [dye] vat where he had been at work.’24 This vivid depiction of the corpulent Morris as the decidedly not-dead blue man brings together his blue-shirted artisanal identification with an evocation of a European cloth-dyeing and body-art tradition in which woad was used.25 In the course of this chapter I will go on to suggest an even more fundamental association of dermis, ornament and savagery in tattoos of so-called primitive societies. A focus on these themes in relation to aesthetic theory might allow us to look again at the twisting interlaced lines of Morris designs, help us to attend to the thick and thin spiralling, vegetal forms that never just stay on the surface but interlace, weaving in and out, producing a kind of chock-full fleshy depth to the design (Figure 1). Fabric and wallpaper designs clothe the body, or the house, and in the case of Morris’s work the ornament might be said to announce the corporeal rather than occlude it. The linked topics of ornamented fabric, the clothed and unclothed body and pigmented skin form a repeated motif in Morris’s late work News from Nowhere (1890), as the narrator Guest discovers the nature of the beautiful in a future society. All the inhabitants are well nourished, strongly muscled and comely, but the contrast between the white skin of Clara with her beautiful gown and the brown skin of the country Ellen who is barefoot and lightly clad leads Guest to recognise that there is the greatest beauty in the suntanned body.26

Terry Eagleton in The Ideology of the Aesthetic (1990) traces the redefinition of the aesthetic in the nineteenth century and points out the way in which the Romantic challenge to Kant’s abstract formulation (discussed in relation to Schelling and Fichte in particular) was reworked yet again by Marx. The question he approaches is how the aesthetic is located: whereabouts in the range between reason and feeling or sensuousness, whether it is conceived of as ultimately abstract or concrete, whether it appears as an idealist or materialist formulation. The relationship between object and subject, form and content and humankind and nature are gauged in each position, and the position elaborated by Marx, less in his stray comments on art than in his entire philosophical and historical method, is described in terms of a recombination of elements that were sundered by previous theories of the aesthetic. If aesthetics, from the eighteenth century onwards, promises a place for the world of sense and feelings within the scope of reason, and then frets about how this can be – and this fraught and ongoing project is indeed one in which Marx participated – then Marx’s theory can be seen as offering one solution to the conundrum and be understood to envision a social order which permits the full functioning of the aesthetic. According to Marx, the incapacity of the deprived proletarian for full sensory existence (instead the proletarian experiences sheer material need) precludes a full aesthetic experience on the part of the worker. The excessive indulgence of the bourgeois, cast adrift from use and material anchoring, produces something that appears to be aesthetic but is similarly one-sided because it is, like money, self-referential, and corresponds to an idealist philosophical position. In Eagleton’s summary: ‘The human body under capitalism is thus fissured down the middle, traumatically divided between brute materialism and capricious idealism, either too wanting or too whimsical, hacked to the bone or bloated with perverse eroticism’.27 The solution is to recombine these two halves and the potential of communism is that the choice between objective existence and subjective experience need no longer be made. The way that William Morris employs the notion of artistic expressiveness and aesthetic pleasure to model the harmoniousness and joy of a social order beyond capitalism does not just depend on the chance combination in his own life of an enthusiasm for art and the onset of socialist convictions. Rather we can consider the vocational location of this individual in the art world as something that gave him a particular opportunity to articulate (in his rough and ready style) the aesthetic positions that could be said to be inherent in Marxist theory – made him, in a way, a privileged exponent of this aspect of Marxist theory.

Figure 1 William Morris, Pimpernel, wallpaper, 1876. V & A Images/Victoria & Albert Museum

One thing that emerges particularly clearly in Eagleton’s presentation is the importance of Marx’s redefinition of the role and position of the body in conceiving of a rapprochement between the practical and the aesthetic, between the brutality of biology and matter and the refined capabilities of thought.

If the rift between raw appetite and disembodied reason is to be healed, it can only be through a revolutionary anthropology which tracks the roots of human rationality to their hidden sources in the needs and capacities of the productive body.28

A discussion of fetishism and commodity fetishism immediately follows on from this statement and this offers one way of interpreting the phrase ‘revolutionary anthropology’, but, beyond this, the way that Marx conceives of human history as the history of human interaction with the natural world is understood as offering a twist on anthropological accounts of man as a toolmaker. Marx’s position is established (following Elaine Scarry)29 as one in which the interaction with nature involves a projection of the human body into the world through its social and technological operations. The stages of history do not, therefore, just consist of objectively existent productive forces, but of the deployment and enjoyment of the sensory capacities of human beings.

What he calls ‘the history of industry’ can be submitted to double reading: what from the historian’s viewpoint is an accumulation of productive forces is, phenomenologically speaking, the materialised text of the human body, the ‘open book of the essential powers of man’. Sensuous capacities and social institutions are the recto and verso of one another, divergent perspectives on the same phenomenon.

In other words, the world, conceived of as the social world and the world made over by man’s efforts with technology, can be understood as both objectively existent and as an aspect of subjective human experience in which the senses (so vital to the aesthetic) have play. There does exist, then, the potential for the fissure between subject and object, sense and reason, to be healed. I am interested in the way that such a philosophical manoeuvre relies upon developments in anthropology which were, in turn, closely entwined with nineteenth-century art discourse.

Nineteenth-century anthropology which was concerned with the origins of humankind was also marked by a debate over the origin of art. Positions varied as to whether art was originally representational, in the service of religion or magic, and degenerated into mere geometric pattern making as the meaningful motif was copied and miscopied, or whether pattern making derived from some other source. Following the influential work of Gottfried Semper the idea became common that pattern making derived from the technical features of different crafts.30 Constructional elements in one material were emphasised by the maker and eventually were carried over as sheer ornament onto wares in other materials, the most basic technique being assumed to be sorts of weaving. The rhythmic interweaving of flexible twigs around posts in wattle fencing and the geometrical criss-crossing of rush or textile matting both produce geometric patterns: the wavy or serpentine line, and zigzags. These ornamental motifs then appeared on materials other than textiles. Ornament then metaphorically clothed objects (and buildings), as patterned textile mats might literally clothe a wall.

In examining the anthropological discussions of the nature and function of ornament it is possible to map out two basic positions; one gives priority to symbolic associations and tends to see geometric ornament in terms of a degeneration of realistic representation – this we can call the semiotic position31 – while another allows for the chronological and logical priority of ornament (divorced from symbolism).32 In this argument the feeling for art is presented as the feeling for pure form. The key point that I want to emphasise is that this second position allows for the idea of a universal sense of the aesthetic and links the aesthetic with the very fact of being an embodied, active social being. In this case body art is acknowledged as indicator of aesthetic potential, and, in the case of tattoos, bodily ornament can image this notion of the aesthetic with great economy, since the design is both outside the body, on the epidermal surface, and inside the body, as the dye penetrates to the dermal layer.

John Lubbock can be identified with the first position. Lubbock’s Origin of Civilisation (1870) touched on the question of body art which he considered to be ‘almost universal among the lower races of men’;33 he felt able to generalise, saying ‘savages are passionately fond of ornaments’.34 He did not, however, see a correlative artistic impulse. The beauty of the Maori tattooing was acknowledged in the book, and contrasted favourably with that of the Sandwich Isles, where devices were described as ‘unmeaning and whimsical, without taste and in general badly executed’.35 Nevertheless there is no assumption that the Maori people have any artistic taste or aesthetic impulse. The aesthetic is located in the eye of the (European) beholder: European travellers find tattoos beautiful, Lubbock explained, because they clothe the otherwise offensive nakedness of savage peoples.36 The motivation of the Maoris was explained in terms of their wish to emphasise the bravery of the subject (willing to undergo the agonising process) and the tattoos’ function to serve as a mark of personal identity, a kind of signature. Fijian hairstyles are admittedly inventive but not for a moment are they considered to be artistic: ‘Not a few are so ingeniously grotesque as to appear as if done purposely to excite laughter.’37 In general, personal decorations evidence individual fancy and clan markings and serve as signs of achievement. Predictably, Lubbock brings out the standard anecdote regarding primitive peoples:

Dr Collingwood, speaking of the Kibalans of Formosa, to whom he showed a copy of the Illustrated London News, tells us that he found it impossible to interest them by pointing out the most striking illustrations, which they did not appear to comprehend.38

Like Tylor (in Primitive Culture) Lubbock opposes the idea that the ‘primitive’ people he is studying are the degenerate heirs of previous civilisations. He uses the anecdote about the newspaper illustrations to support his contention that primitive peoples really are at a preliminary stage of development; this involves a deficiency in artistic sensibility.39 He also seeks to demonstrate a lack of moral sense and a dependence on brute force. Unlike Tylor he sees the progress from the prehistoric to the modern as one in which a fundamental shift in human nature takes place, as unredeemed savagery gives way to blessed civilisation.

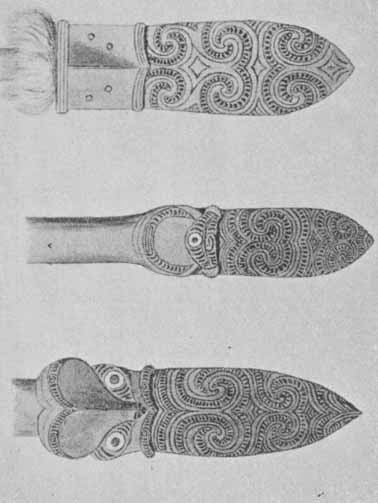

The assumptions that we find in Lubbock had their echoes later in the century and became associated with the argument that ornament was a result of the gradual loss of realism and symbolic significance. A key voice in the debate was William Goodyear. In his The Grammar of the Lotus (1891) he argued that apparently abstract ornament can be traced back to the presentation of plant forms and that the rationale for the introduction of particular plant motifs was their significance in religious contexts.40 This method was followed by Henry Balfour, for instance in The Evolution of Decorative Art (1893). He ruled out a preliminary stage of the aesthetic (in body art) by classifying it as nothing more than an animal impulse akin to a magpie seizing something shiny to decorate its nest.41 This left his main emphasis as the tracing of suppressed symbolic associations that had been lost in the tangled threads of conflated motifs, miscopying and conscious variation. The anthropologist’s task, he said, was to reconstruct the sequence. For example, he discussed the spiral ornament on Maori objects and called for the patterns to be interpreted (Figure 2). We should recognise the protruding tongue, he asserted, significant in Maori culture as a sign of warlike strength, and so incised in designs which become incrementally conventionalised. He assembled a sequence showing that head and protruding tongue give way to conventionalised one-eyed face with tongue, and eventually to a tongue with no face at all: ‘the all-essential tongue remains unchanged, symbolic to the last, but with no context, so to speak, to explain its meaning, if seen apart from other more complete, and therefore more realistic examples’.42 The challenge of tracing symbolic meanings was great, and at times Balfour expressed frustration:

This fusion of the parts of several designs leads to very complex derivatives, presenting frequently an apparently inextricable confusion of ideas to him who would unravel the separate lines of growth, which have, so to speak, been plaited together in various combinations, till at length the original conception is completely obscured in a web of tangled threads.43

The use of a tangled web as a metaphor for ornament is deliberately self-referential and revealing as to Balfour’s perception of ornamental design. For Balfour the lines of the pattern represent so much frustrating confusion.

While Lubbock, Goodyear and Balfour can be identified with the refutation of an inherent aesthetic sense in primitive peoples, and their emphasis is on the symbolism attached to ornament, another group of commentators can be picked out who understood primitive art in different terms. Owen Jones, in The Grammar of Style (1856), referenced Maori artefacts and Maori tattooing as examples of primitive ornament. Crucially, though, Jones did not seek to find a semiotic explanation for the motifs nor did he exclude such ornament from the realm of the aesthetic. He claimed that refined taste, judicious skill and evidence of mental kinship, ‘the evidence of that desire to create’, are what the modern European is surprised and delighted by.44 His brief, enthusiastic comments, exceptional for the 1850s, set him apart from the symbolic significance position that we have been considering. The aesthetic positioning of the artefact involves the western viewer in a form of identification, as he responds with pleasure and recognises an artistic disposition like his own in the far distant maker.

By the 1890s some much more elaborate and developed theories posited ‘savage’ or ‘primitive’ ornament as evidence of a universal aesthetic sense, and relied on the examples of tattooing or body art to back up this argument. Alois Riegl was concerned to trace the historical morphology of ornament on a worldwide scale and into modern times, and to challenge Semper’s method, which was dubbed ‘materialist’. This argument emerged most clearly in Problems of Style (1893).45 In some ways Riegl made concessions to the position that saw ornament as semiotic in origin, and so linked artistic practice to the dissemination of socially accepted or enshrined values. He cited Goodyear’s The Grammar of the Lotus, albeit with reservations, and was prepared to accept the argument about stylisation of plants which may originally have had ritual associations; indeed his Problems of Style, which is a history of curving tendril ornament, could be read as an attempt to use Goodyear against Semper.46 Nonetheless Riegl’s understanding of the way in which ornament comes about is that it comprises a basic universal aesthetic urge as well as historically contingent readiness to turn ornament to the services of ritual, or orient art to nature in phases of naturalism. The creative act is not the imitation of nature, despite the fact that he is ready to admit, as he does in the very first sentence of Chapter 1, that ‘[a]ll art, and that includes decorative art as well, is inextricably tied to nature’.47 His emphasis is not on mimesis but on the transformative creative act. The translation into two-dimensional graphic form is therefore held to be more challenging and creative than a replication in a three-dimensional sculptural form. It may be, he argues, that the lotus motif was a founding element in Egyptian decoration and then persisted in altered forms; maybe (though here his scepticism is amplified) its introduction can be attributed to its symbolic importance for the sun cult – in that respect it is possible to grant a place to naturalistic reference and symbolism. But, and this is where he diverges from Goodyear, the moment of its introduction was a moment of creative transformation of nature in stylisation, as the natural object is rendered in the flat in outline, and then subject to the geometry, symmetry and rhythm of pattern making. Once the vegetal element gets into ornament it is as if art infuses it with a fresh life; it is able to twist and turn and morph and branch and blossom in an unstoppable sequence of invention and variation. Thus the tendrils that he documented in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek, Islamic and European medieval and Renaissance art, as they grow and spread and interlace, seem to instantiate the very substance of artistic creativity. The term he used later in Late Roman Art Industry of 1901 to describe this wellspring of artistic feeling was Kunstwollen and it is important to realise that Kunstwollen is a term that embraces both the stylistic preferences of a place or epoch (we can think of this in terms of the characteristic disposition of lines and rhythm of ornament) and a more fundamental will to make and experience art that transcends location (which perhaps can be thought to subsist in the lively, ubiquitous line itself).

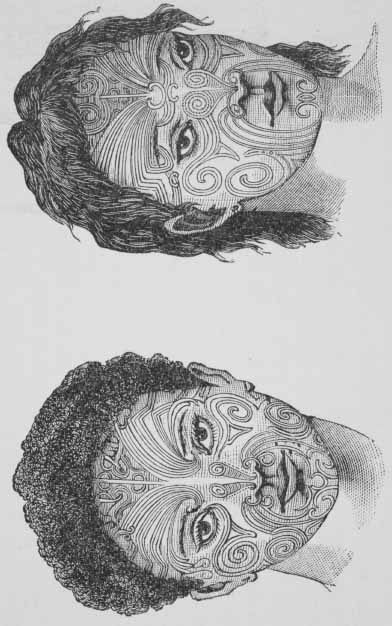

Riegl’s trump card against both Semper and Goodyear was that artistic feeling exists in societies without developed textile crafts and where no representational symbolism is evident. He picked the example of body art in Maori tattooing, claiming for it a sheer joy in geometric ornament.48 Riegl reproduced his plates for the section on tattoos from Lubbock’s work, but his argument is the polar opposite of Lubbock’s (Figure 3). Riegl explained that the spirals could not be linked to pottery or metalwork since these materials were not worked by the Maoris. They could not be explained in terms of transmitted patterns since Maori culture was, he argued, isolated. Ornament must then be seen as the highest rather than the lowest aspect of art because it gives most eloquent expression to the intrinsic human artistic impulse. Rather than being conceived of always as supplement, as play or fancy superadded to the substantial or reasonable, ornament could be considered as a structurally necessary aspect of art to which symbolism is conjoined.49 I would suggest that the fact that Riegl locates ornament in and on the body is significant, in the light of the argument I have presented about Marx’s employment of the technologised world as ancillary to the body in the revisiting of the aesthetic conundrum, thereby resisting the Kantian solution of isolating pure reason, and equally resisting the Romantic riposte which depended on flooding the world with subjectivity and sensation.

The climate in anthropology had changed considerably by the 1890s, when Riegl was working on his theories. Space had gradually been opening up in anthropology for an acknowledgement, firstly, of the chronological and logical priority of ornament, secondly, its independence, on occasion, from symbolic association and thirdly, ornament’s possession of an aesthetic purpose as well as a pleasing appearance (to Europeans). Major General Robley, in his detailed and authoritative work Moko: or Maori Tattooing (1896), was explicit about the classification of this form of ornament as art, pointing out that individual tattooists were not anonymous in their own culture, but celebrated for their individual skills, like painters in the modern world.50 Other commentators were prepared to leave a place for the purely aesthetic.51 This involved challenging seamless sequences of influence and borrowing. Alfred C. Haddon, author of Evolution in Art (1895), was at pains to distinguish spiral design in New Guinea from Maori scrollwork (and challenged Goodyear’s account of cultural transmission). New Guinea spirals are allowed to be derivatives of bird and crocodile designs, but Maori scrollwork is said to be generated in isolation and first of all to come from an impulse to decorate the body by accentuating the rounded elements:

My impression is that the carved designs have been derived mainly from tattooing, and … when one looks at tattooed Maori heads or carvings of human figures one finds that rounded surfaces … are usually decorated with spiral designs; this is in such places an appropriate device, as it accentuates the features which are ornamented, and personally I am inclined to believe that artistic fitness is the explanation of this employment of the spiral, and that it has been transferred to other objects as being a pleasing design, and that connecting lines have been made to give coherence to the decoration.52

Here then was a commentator who made a separate place for art among the motivations for ornament. The impulse to beautify an object was held by Haddon to be common in all ages and to all humanity and this premise allowed him to conceive of a continuity between the aesthetic forms of ‘primitive’ societies and those of modern western Europe.53

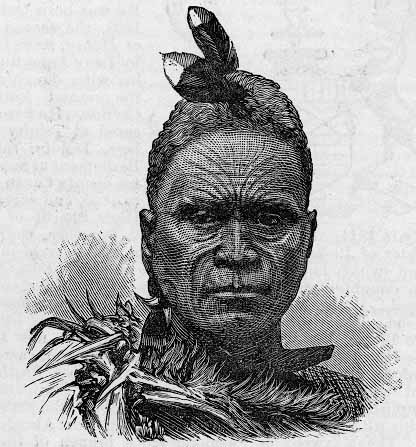

Morris was an avid reader on a great variety of subjects. We can be sure that he knew Owen Jones’s work and it is highly probable that he was familiar with Semper’s. His interest in early society was stimulated by his investigations into Icelandic culture and, from the 1880s, by his political contact with Engels. In the series of articles ‘Socialism from the Root Up’ (1886) he gave an account of the development of primitive society in times of barbarism, from individual hunters to the emergence of primitive society organised round the gens in early agricultural times – a form of primitive communism that in turn gave way to the emergence of private property and the tribe, described as the last stage of barbarism.54 It has been argued that he probably read Lewis H. Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877) and Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884).55 Morris collected illuminated and early printed books and had a 1637 edition of William Camden’s Britannia, which contained engravings and described the tattooing practices of the Picts and Celts using woad, ‘their cutting, pinking and pouncing of their flesh’.56 It is interesting to speculate as to whether he knew the engraving after Le Moyne ‘Truue picture of a young dowgter of the Pictes’, one of the engravings of indigenous British tattooing from De Bry, America (3 vols, 1590–91), or other engravings from John Speed’s The Historie of Great Britain (1611), which reproduced some engravings of Picts from De Bry.57 The tattooed pictures on the skin of the Picts – in some cases ‘their whole body was garnished over with the shapes of all the fairest kind of flowers and herbes’58 – were illustrated and described, and these striking images would surely have fascinated Morris.59 Perhaps he also registered the presence in England of the Maori chief, Tawhaio, who caused a sensation on his visit to the country in the 1880s. His tattooed face was depicted in the pages of the popular press and reporters questioned him about his attitudes to English female beauty, and told of his quaint manners and his prodigious appetite for roast beef and shellfish (Figure 4).60 Robley recounts that a firework display was mounted in his honour at Sydenham:

At the Crystal Palace on the occasion of his visit, there was a special display of fireworks, which included a pyrotechnical representation of his face. Messrs Brock &Co. used blue lights to represent the tattooing marks, and it was reserved for that celebrated firm of fireworkers to achieve the apotheosis of the moko.61

Morris had a lifelong aversion to fireworks, but the ornamental lines themselves, in the dermal substance of Tawhaio’s face, standing as incorporated ornament and offering evidence of a universal aesthetic impulse, might have been meaningful to him.

The change in the frame of reference that I have alluded to, represented in this chapter by the figures of Riegl, Robley and Haddon, offers a counterbalance to the position adopted by Nordau in Degeneration, which disgusted Morris so much.62 Morris could not have arrived at the formulations he propounded in the 1880s had the intellectual terrain not been shifting. Positions concerning the roots of aesthetic experience were being disturbed by the reassessment of ornament that took place in anthropology. Morris should therefore be seen as a participant in the ongoing debates about art, human identity and cultural evolution. Other Marxist formulations emerge in the second half of the nineteenth century against the background of these debates; Plekhanov, for instance in his ‘Letters Without Address’ (1899–1900), works systematically through a vast range of ethnographic authorities including Tylor and Lubbock to arrive at the position that the aesthetic sense is not primary. He is quite clear that aesthetic pleasure follows on from activities of economic importance; play derives from labour and not vice versa. When he comes to the question of the motivations for body art and tattooing he offers action against insects and the sun and surgical procedures as possible first stimuli and then the semiotic issues of marking out the relationship of the individual to the gens and recording the life of the individual or the community. Only after this is there any sense that this decoration appears beautiful.63 Morris had a Marxist aesthetics that turned the argument a different way. For Morris the requirements of labour could not be seen as prior to another department of human life concerned with artistic feeling and aesthetic pleasure because labour was itself (ideally) the locus of pleasure; pleasure in labour was the fount of art. Furthermore, Morris believed that ornament had to participate in a rejoining of subject and object. Colour and pattern had to get under the skin, like the dye from a tattooer’s needle, not just because the artist gets his or her hands dirty artisan-style, but because the aesthetic functions in an environment patterned by its crafty inhabitants and above all because the aesthetic comes from within. There is a marked focus in much twentieth-century Marxist art history and literary history on iconography and the identification of ideological positions.64 By turning afresh to Morris as one of the first Marxist commentators on the making and the study of art we can see that there was, from a very early stage, the articulation of another way of approaching art and its history, one where the primary emphasis was on aesthetics and form.