The displacement of central European intellectuals due to the rise of fascism brought to Britain three leading Hungarian art historians – Frederick (Frigyes) Antal (1887–1954), Johannes Wilde (1891–1970) and Arnold Hauser (1892–1978). All had been active in the Hungarian Soviet Republic at the end of the First World War but since then had followed separate paths. They also went on to establish very different reputations in the English speaking world. Wilde became professor and deputy director of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, where he taught successive generations of students in the art of the High Renaissance. Hauser, something of an outsider to the British art establishment, was a lecturer in the University of Leeds during the 1950s, his books reaching an audience beyond the confines of academic art history. But it was Antal, who never occupied a permanent position in any British museum or university, who initially exerted a more profound influence in his adopted country. He did this in two ways; firstly by introducing a rigorous method of the ‘social history of art’ inspired by classic Marxist principles, which he demonstrated in the major book Florentine Painting and its Social Background,1 and secondly by focusing his interest on British artists who had received little serious attention from art historians trained in the classic techniques of the discipline. When Antal’s books on Hogarth and Fuseli were published after his death, they were instrumental in establishing a new phase in the scholarship of British art, a point made by many historians when the books were reviewed in the academic and popular press.2

By the time he arrived in Britain in 1933, Antal had already passed a considerable career as an independent scholar in central Europe.3 Born in Budapest to a wealthy Jewish family, he had initially studied law at the university there before taking up art history, first in Budapest and then in Freiburg and Paris. The early years of the twentieth century were, as Antal himself described it, the ‘heroic’ period of art history4 with a number of influential figures establishing schools to develop their theories of Kunstgeschichte and Kunstwissenschaft. Antal entered the mainstream of this burgeoning academic industry becoming a student of Heinrich Wölfflin at the University of Berlin.

During his tenure of the chair of art history at Berlin (1901–10), Wölfflin enjoyed immense prestige, his lectures attracting large audiences of students and the general public.5 As the protégé and intellectual heir of Jacob Burckhardt, Wölfflin developed one of the most coherent methodologies for the study of art works as historical phenomena. Classic Art, first published in Munich in 1899,6 exerted a great influence on scholars throughout Europe and introduced many of the tools for historical interpretation that Wölfflin would later present in Principles of Art History (1915).7 In essence, what Wölfflin was outlining in this theoretical text was already implicit in many of his previous publications: that the history of art has its own pattern of development, and that there is a teleological sequence in which certain features in the appearance or style of the art works can be observed to follow a logical and inexorable process. To demonstrate the sequence Wölfflin identified a set of five ‘polarities’, pairs of opposed visual concepts, which, in the transition from one to the other, indicated the sequence in progress: the development from linear to painterly, from plane to recession, closed form to open form, etc. This was ultimately linked to a cyclical view of history, similar to that proposed by Winckelmann, whereby the dynamic conditions in which art works are created and used makes them a necessary part of the sequence.

If Wölfflin’s ‘system’ seems somewhat mechanistic nowadays, there was no denying its power at the time because it offered a theory of artistic development that was independent of social, economic or political forces. In other words, a history of art based on formal characteristics alone that was not subservient to other forms of history. This was one of Wölfflin’s stated aims since he believed that the new discipline of art history (Kunstgeschichte) should not be merely ‘illustrative of the history of civilisation’ but that it should ‘stand on its own feet as well’.8 It was precisely in this respect, however, that Wölfflin’s teaching seemed unsatisfying to Antal, since the ‘formalist method conceded, relatively, the smallest place to history’.9 Reviewing these methodological alternatives in 1949, Antal remarked that ‘Wölfflin’s very lucid, formal analyses … reduced the wealth of historical evolution to a few fundamental categories, a few typified schemes’, going on to dismiss this approach as a reflection of the prevailing aesthetic doctrine of ‘art for art’s sake’.10 In reaction to Wölfflin’s model, Antal moved in 1910 from Berlin to Vienna, a city that was emerging as the pre-eminent centre for art-historical research in Europe.

The ‘Vienna School’, dominated at this time by Max Dvořák (1874–1921) but with the looming intellectual legacy of Alois Riegl (1858–1905) and Franz Wickhoff (1853–1909), offered a more sophisticated intellectual environment within which to study works of art. Antal later remarked on the ‘great difference in the spiritual atmosphere’ between Berlin and Vienna, not least because the art-historical institute was located within the larger framework of the Austrian Institute for Historical Research (Kunsthistorische Institut des Instituts für Oesterreichische Geschichtsforschung).11 The central figure behind the ideological principles of the ‘Art Historical Institute’ was Riegl, keeper of textiles at the Decorative Arts Museum (Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst) and, from 1897 until his death in 1905, professor of art history at the University of Vienna. In the last decade or so of his career, Riegl had formulated the most sophisticated and wide-ranging approach to the historical interpretation of artefacts, to the extent that he has often been described as the first modern art historian.12 Although perhaps best known for the concept of Kunstwollen or ‘the will to form’, there were two aspects to Riegl’s art history that may explain his importance for later scholars. The first of these was adherence to Hegel’s idealist conception of history, in which works of art enjoyed a privileged position, not just as bearers of aesthetic meaning, but as keys to the underlying ‘world spirit’. In other words, the work of art in history was felt to reveal deep structures of the culture that produced it. Imbuing art works with a significance beyond that of simple archaeological data was one of the founding assumptions of art history as an academic discipline. Secondly, and also derived from Hegel’s view of history, Riegl’s approach to continuity of stylistic development had a profound and practical influence on his immediate followers. This fundamental principle appeared in Stilfragen (1893), his first major publication, in which he traced the development of lotus and acanthus motifs in ancient ornament as an example of the ‘evolutionary’ model of stylistic change.13 The key element was that, for Riegl, change in art was understood as part of a linear or historical continuity, quite separate from later assessments of quality or beauty. Furthermore, stylistic development was seen as neither a response to the immediate material conditions, as Gottfried Semper had advocated, nor a symptom of the relative rise or fall in civilisation, as Wölfflin believed. For perhaps the first time, this approach offered a view of cultural artefacts as part of a development through history unrelated to questions of quality or indeed to popular assumptions regarding historical periods as culturally superior or inferior. For Dvořák, and for Antal, this represented ‘the victory of the psychological and historical conception of art-history over an absolute aesthetics’.14

One of the effects of this on the research undertaken by Viennese scholars was an increasing interest in the so-called ‘dark periods’ or ‘periods of decay’,15 which Wölfflin had regarded as symptomatic of the downswing in his cyclical model and which many earlier historians had interpreted as signs of cultural decadence and decline.16 Riegl, Wickhoff and Dvořák each took a serious interest in periods or movements such as late antique, early Christian or Mannerism which had been dismissed by previous historians as insignificant or aesthetically unworthy of detailed study.17 In addition, Riegl’s influence meant that all the leading members of the Vienna School upheld the principle that formal analysis was the basic analytical tool of the art historian, seeing style as the indicator of artistic development and the bearer of deep cultural meaning. But whereas Riegl himself had placed considerable emphasis on the mechanism, or force, which drives stylistic change, (the Kunstwollen), Wickhoff and Dvořák sought increasingly to develop an approach in which the social and economic context of artefacts was seen to exert a decisive influence on their form and appearance. The outstanding early example of this is often taken to be Dvořák’s essay ‘The Enigma of the Art of the van Eyck Brothers’ of 1904, in which he suggested that the apparent stylistic originality of early Netherlandish painting was not only related to naturalist tendencies in late Gothic illumination of the previous generation, but that this was able to develop specifically within the economic and social patterns of fifteenth-century Flanders.18 Dvořák, who had always embraced a wider set of interests, went on to publish several key texts which maintained the central role of form in pictorial analysis but gave increasing weight to the expression of a ‘world view’ (Weltanschauung) rather than an internal motive force as the decisive factor.

Dvořák’s contribution to the methodological basis of the Vienna school has been summed up as the introduction of an ‘intellectual, history-based approach’ alongside ‘Wickhoff from the stylistic, and Riegl and Schlosser from the linguistic–historical standpoints’.19 He is also frequently associated with an approach inspired by contemporary ‘expressionist’ ideas that imbued the artist in history with greater independence of stylistic choice.20 But this overlooks two of his most important intellectual legacies. Dvořák’s attempts to locate artworks within the larger spirit or ‘world view’ of their age meant that the history of art could be seen not solely as a continuum but as a series of shifts and breaks reflecting the character of successive periods which presented significantly different social structures and formal preoccupations. It also introduced the possibility of a social history of art in which artefacts could be understood and interpreted in terms that reflected the society in which they were created.

Antal was at the centre of these debates in the years preceding the First World War when preparing for his Ph.D. under Dvořák’s supervision.21 The material of his thesis, entitled Classicism, Romanticism and Realism in French Painting from the Middle of the Eighteenth Century until the Emergence of Gericault, was not published at the time, but a version of the argument appeared many years later in English as ‘Reflections on Classicism and Romanticism’22 – although this was clearly influenced by ideas and approaches which Antal developed after leaving the rather introverted environment of the Vienna School.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Antal returned to Budapest, where he worked in the prints and drawings department of the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts). This was an important phase in Antal’s development as an art historian since it was here that he acquired the skills of close visual analysis, particularly the connoisseurship of old master drawings, that were much admired in his later career.23 By 1916 he had also begun to attend the salon or discussion group known as the Sonntagskreis (Sunday Circle), an informal group of intellectuals and artists who met at the house of the writer and film theorist Béla Balázs (1884–1949). The central figures of the group were Balázs and Georg Lukács (1885–1971) and their friends Leo Popper and Karl Mannheim, but the circle of about 30 extended to include musicians, such as Béla Bartók, and the art historians Arnold Hauser and Johannes Wilde as well as Antal. As an outlet for their developing ideas, in 1917 the group set up the Free School of the Cultural Sciences (Geisteswissenschaften) offering talks on a variety of subjects related to the condition of modern bourgeois culture.24 Lukács, for example, spoke on Dostoevsky, Mannheim on ‘Soul and Culture’, and Antal on Cézanne. Given the fluid nature of their ideas and the range of individuals involved, it would be rash to attribute any singular philosophy or outlook to the group as a whole. But one can make general observations on the overall character of their interests from Lukács’ diaries and reported statements, dominated as they were by the seminal shift in his intellectual life. Between 1916 and 1918, Lukács was moving from an essentially ‘Romantic’ or idealist view of life and art to one informed by the historical materialism of Marx. In fact, Lukács’s full acceptance of a Marxist view of society and culture can be dated to a specific meeting of the ‘Sunday Circle’ in November 1918 when he announced, ‘Now I realise that only a consciously redeemed man can create the empirical world. I have to re-evaluate all of my thinking. If we believe in human freedom, we cannot live our lives in class-fortified castles’.25

This dramatic ‘conversion’ is misleading, however, since it masks a long and complex period of self-questioning on Lukács’ part. For several years Lukács and other members of the circle had been wrestling with the relationship between the art and culture of a given period and the society which brought them into existence and which, in turn, shaped their nature and content.26 Karl Mannheim, for example, worked up this same set of issues during the next decade into a body of theory which became known as ‘the sociology of knowledge’. In works such as Conservative Thought (1927) and Ideology and Utopia (1929), he argued that there was an association between forms of knowledge (or ‘modes of thinking’) and social structure, and that membership of particular social groups or classes conditioned patterns of belief.27 For Mannheim, these claims were not dependent on a Marxist model of society and historical change.28 For Lukács, however, and for Antal and Hauser, this was the fundamental assumption which governed their later research and writings.29

In the preface to the 1967 edition of his most influential work, History and Class Consciousness (1923, English edition 1971), Lukács recalled the period c.1917 to 1920 as one in which he grasped the essential principles which would govern his intellectual life thereafter. Lukács was at pains to emphasise, however, that this was not a simple or logical move and that his intellectual journey had been complicated by many diversions and sidetracks, some of which were inconsistent and contradictory.30 Yet Lukács was in no doubt about the overall tendency of his thinking in the years around 1918, which he summed up in the title of an autobiographical sketch called My Road to Marx (1933). A reading of this alongside History and Class Consciousness reveals the central thrust of Lukács’s project which was no less than the development of a comprehensive philosophy of culture on Marxist principles; but one that rejected or at least offered a radical revision of the classic Marxist model of ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’ to describe the relationship between economics and culture.31 In this traditional view, to quote Raymond Williams, ‘art is degraded as a mere reflection of the basic economic and political process on which it is thought to be parasitic’.32 Lukács’s position would prove to be controversial throughout the 1920s and beyond, attracting considerable criticism from orthodox Marxists.

A more immediate problem, however, was the relationship between Marxist theory and political activism.33 To some extent the tension between theory and practice was resolved in the Hungarian Soviet Republic set up under Béla Kun in March 1919 following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of the First World War. Both Lukács and Antal took official positions in the provisional government, Lukács in the ‘People’s Commissariat for Education’ and Antal as Director of Museums in Budapest (Vorsitzender des Direktoriums). In this role, Antal supervised the transfer of many private art collections to the public galleries and, with the assistance of Otto Benesch, organised exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts. Paralleling the work of Dvořák, who was curator of public monuments in Austria and closely involved in contemporary art, Antal also set up public art projects, found support for artists and led efforts to protect existing public monuments in Budapest and its immediate hinterland. This was short-lived, since the ‘Republic of Councils’ was suppressed after foreign intervention in the summer of 1919, at which point Antal, Lukács and most of their colleagues fled to Vienna.34 One senses, nevertheless, that the experience of direct political engagement and the involvement in a revolutionary movement at a high, if essentially administrative, level must have been a strong influence on Antal’s subsequent outlook.

The inter-war period was one of uncertainty and displacement for Antal, but it was also the period when he pursued most of the research that formed the basis of his major publications. Between 1919 and 1923 he travelled in Italy where he gathered material for a projected book on sixteenth-century art that would have elaborated some of Dvořák’s pioneering work on Mannerism. This was never completed, or at least never published35, but Antal did undertake the primary research on Italian art and society of the early Renaissance which would eventually appear in Florentine Painting and its Social Background (London, 1948).36 Following this, he took up residence in Berlin where he collaborated with Bruno Fürst and Otto Pächt, editing Kritische Berichte, a journal devoted to the literature of art history and to issues of theory and methodology.37 This preoccupation with theory allowed Antal to synthesise many of the disparate and often conflicting ideas he had absorbed during the previous decade, from the likes of Wölfflin, Dvořák, Marx and the various members of the Sunday Circle. Here again, one senses that Lukács may be a guide to the theoretical problems and possible solutions that confronted this group of Marxist and socialist intellectuals in the Weimar years.

In the 1967 preface to History and Class Consciousness, Lukács writes ‘mental confusion is not always chaos’, suggesting that this description of his own mental processes when dealing with complex problems could be taken as a metaphor for the dialectical processes of history as Hegel and Marx understood it. ‘It may strengthen the internal contradictions for the time being but in the long run it will lead to their resolution.’38 This drew Lukács to concentrate on issues where the ‘internal contradictions’ of capitalism could be observed at their most extreme and unstable. The result was a lengthy examination of the historical novel in the nineteenth century, an art form which he believed was the most characteristic expression of the bourgeois world view and, despite its unpopularity with Modernist critics, the literary form which deserved the closest attention because of its special status.39 This was a controversial position to maintain, because it placed Lukács between conflicting theories of art that were themselves highly politicised in the inter-war period. In simple terms, Lukács was mounting a defence of an art form (the realist historical novel of Walter Scott, Balzac and Tolstoy) which seemed outdated to the Modernists, but which had also been compromised by the tendentious products of official Soviet policy towards the arts under Stalin. As a result, Lukács stood at the centre of a complex debate on aesthetics and politics undertaken by some of the leading intellectuals of the day, including Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch and Bertolt Brecht.40 At the heart of this was the issue of ‘realism’ which, for Lukács, was not a period or style, but a literary mode that embraced the totality of society, reuniting the fragmented experience of capitalism. In elevating the work of Thomas Mann over that of Franz Kafka, for example, Lukács was emphasising the continuing relevance of this essentially ‘rational’ bourgeois tradition in contrast to the ‘irrationalism’ of much Modernist literature.41

There is a parallel to this view in Antal’s identification of a naturalist or ‘realist’ tendency in art as the visual impulse of the aspirant middle classes. Alongside this, Antal sees class antagonism as the reason for the coexistence of divergently different styles in the art of a particular period. In fact, these two related concepts might be regarded as the thread linking all his major publications. Despite a wide range of interests, spanning the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries and embracing major figures and movements in Italy, the Netherlands, France and Britain, a recurring theme is the extent to which the bourgeoisie are able to assert their identity in the visual arts as a reflection of their political and economic position.

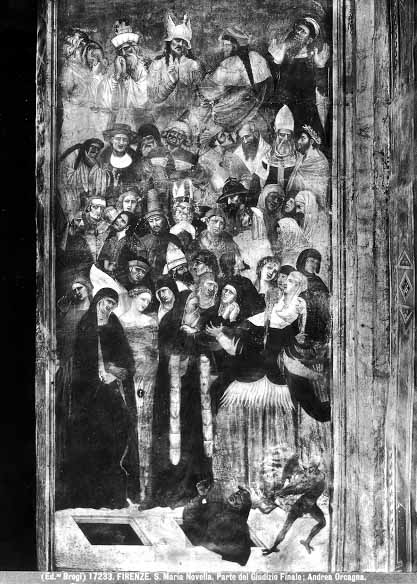

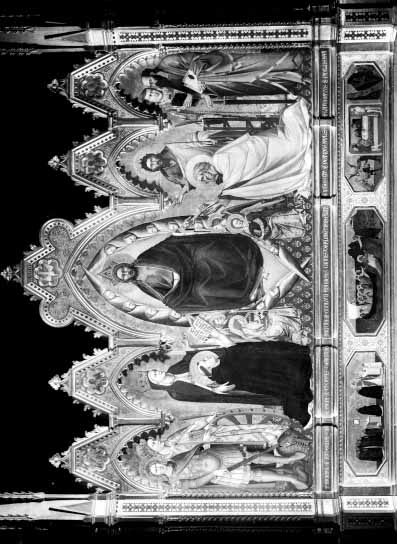

In Florentine Painting and its Social Background, this is the overriding principle, shifting the emphasis from painters and studios to the new class of patrons, the ‘oligarchic upper bourgeoisie’ which had gained a ‘position of economic and political supremacy over the petty bourgeoisie and the workers unique in the Europe of the time’.42 It proved to be an effective way of interpreting the various stylistic tendencies, especially in the art of the later fourteenth century, which had long been a problem to art historians. In Antal’s reading, the major fresco cycles are seen as an arena of contested visual forms in which competing class interests can be traced to different styles or modes of depiction. Antal uses terms such as ‘rational’, ‘naturalistic’ and ‘realistic’ to describe the Giottesque art of the early fourteenth century which he believed expressed the world view of the progressive upper middle-classes. An example used to demonstrate this is Giotto’s fresco cycle of the life of St Francis in the Bardi Chapel in S. Croce (Figure 5). Painted for the wealthy banker Ridolfo di Bardi around 1320, Antal interprets the orderly composition, the naturalistic rendering of the figures and, above all, the convincing representation of space in this fresco as an expression of the values and outlook of the new upper middle class. ‘In the S. Croce frescoes it becomes particularly apparent how that task of depicting religious stories in a vivid and convincing manner demanded clarity of vision, close observation of nature and all the devices of a logical, nature-imitating naturalism’.43 In contrast to this, Nardo di Cione’s frescoes in the Strozzi Chapel in S. Maria Novella from the mid-1350s represent an opposing tendency in their ‘archaic, hieratic composition’ and limited attempt to create a convincing pictorial space (Figure 6). Antal interprets this not as some independent oscillation between opposing stylistic possibilities, nor as an internal process of evolutionary change, but as the visual expression of competing sections of Florentine society. ‘These frescoes (by Nardo) were painted in the interval between the reign of the Duke of Athens (1343) and the ciompi revolt (1378), when the petty bourgeoisie were pushing their way forward.’44 For these newly ascendent sections of Florentine society, Giotto’s art was too ‘modern’, but the previously dominant class of the upper bourgeoisie who had supported the more ‘naturalistic’ art of Giotto and his followers were in a weaker position by the middle years of the century and could no longer assert their authority in matters of art, any more than they could in politics or economics. As a result, Nardo’s fresco cycle reveals the compromise or concessions of the upper bourgeoisie to the taste of the less sophisticated petty bourgeoisie and their allies the Dominicans. The tendency is further demonstrated in the altarpiece (1354–57) in the same chapel, painted by Nardo’s brother Andrea Orcagna, which displays a curious combination of ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’ elements (Figure 7). Unlike the traditional polyptych, the Strozzi Altarpiece employs a concisely constructed panel with a unified pictorial field, but the figures are treated in a ‘stiff’ linear manner while the colouring is described as ‘unpictorial’, relying on bold contrasts of local colour.

As exemplified in this impressive altarpiece, commissioned by one of the wealthiest families in Florence, the concentrated yet hieratic and two-dimensional idiom of the “upper-bourgeois” artist, Orcagna, represents … a compromise on the part of the upper middle class in accepting stylistic preferences of the lower middle class.45

Antal’s approach depends on a model of the larger pattern of class relations unfolding over a period of some 150 years. To make sense of this, and to provide adequate evidence for his claims, he devotes a large part of the book to explaining the economic, political and religious context. Here he outlines, among many topics, the development of civic institutions, the structure of business and domestic life, and the relationship between secular and religious impulses in society. He also offers several key themes which informed the way pictures were viewed, such as the conflict between the ‘rational’ and the ‘irrational’, the former of which was manifested in ‘sobriety’ and an art which demonstrated ‘a considerable degree of fidelity to nature’.46 The opposite ‘irrational’ tendency favoured a return to conventional modes of depiction utilising symbolic representations of natural phenomena, which, in turn, elicited a more abstract and emotional response from the spectator. Going beyond these themes, Antal also attempted to explain how consciousness of class interests in fourteenth-century Florence was developed and how, in turn, it was ‘reflected’ in formal or pictorial conventions.47 This is addressed in the opening chapter of Section 2 (‘The Art of the Fourteenth Century, and the “outlook” on which it is based’), one of the most revealing parts of the book, which outlines certain underlying principles of Antal’s art history.

It would be a caricature to suggest, as some have, that Antal aligned each class with a specific ‘style’, in the way that a social group might adopt a flag or a team’s colours.48 Nor was he aiming to write a history of taste. Antal sought to identify patterns in the world view and mode of thinking in each class that were shaped by the acquisition of certain mental skills and which corresponded to their conception of the external, ‘natural’ world. The ‘outlook’ of the upper bourgeoisie, Antal suggested, was characterised by their commercial expertise and ‘a manner of thinking by which the world could be expressed in figures and controlled by intelligence’.49 This was never intended as a psycho-social history of the fourteenth-century Florentine merchant class, but as an indication of the ways in which that group might have approached the viewing and interpreting of pictures which they had paid for and which they looked to for affirmation of their role and status. Taken as a means of interpreting modes of observing among sections of the Florentine bourgeoisie, Antal’s approach finds some echoes in Baxandall’s concept of ‘the period eye’, although the latter restricts his study to a specific social group which he further isolates from the larger context of class relations. Nevertheless, a certain similarity in approach and findings is made explicit in Baxandall’s discussion of ‘gauging’ and the taste for ratio, proportion and the orderly description of forms in pictures.50 While Baxandall was concerned with the ways in which the ‘visual skills evolved in the daily life of a society become a determining part in the painter’s style’,51 Antal had a larger project, tracing the pattern of Florentine class conflict as expressed in painting. To make sense of this, Antal had to give his book a considerable chronological time-span which, unlike Baxandall’s narrower set of questions, required some generalisation. Antal was also dependent on the information available from contemporary scholarship in the fields of social and economic history, which has expanded immensely since the book appeared. Despite these qualifications, it is remarkable how much of Antal’s view has filtered into the general textbooks on Italian Renaissance art, although rarely, if ever, is Antal credited with its development.

A similar conflict of class and style was identified by Antal in French art between the Revolution and the Bourbon restoration, as outlined in his 1935 essay ‘Reflections on Classicism and Romanticism’. Returning to themes addressed in his doctoral thesis, Antal picked out a ‘naturalist’ strand as the distinctive feature of progressive painting in this period, instead of the stylistic labels that had traditionally been employed. The ostensible aim of the essay was to demonstrate that, while stylistic categories like ‘Classicism’ and ‘Romanticism’ might still have some currency, they had to be re-examined if they were to reveal the deeper impulses in the art to which they were applied. In particular, he was at pains to emphasise that it was not the formal characteristics alone that made a style significant, but the meaning it carried and the extent to which it embodied the ideals of specific classes or social groups. Underlying this more general discussion of style, Antal was sketching the outlines of a major shift in artistic sensibility corresponding to the establishment of a capitalist system of economic and social relations in modern France.

One of the prompts for this line of argument was Antal’s experience of museum displays in the Soviet Union, which he had visited in 1932. In particular, he had been impressed by how French art was displayed in the Hermitage utilising texts and a range of complementary material to emphasise both the continuity between fine and popular art and, more significantly, their links to social and economic change.52 Antal was also not alone in seeing the diversity of stylistic tendencies in French art of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as somehow indicative of a deeper political struggle. In the early years of the twentieth century the pioneering Russian Marxist Georgii Plekhanov had proposed a similar reading of French late eighteenth-century art, emphasising ‘naturalism’ as the latent but insistent impulse of the bourgeoisie.53 The theme was also taken up by several scholars working independently of Antal to the extent that the notion of a struggle between realist tendencies and the traditional styles of the French court and academy might be seen as a major issue among art historians of the 1930s.54 What is surprising is that this debate was almost entirely abandoned in the post-war period and that it was not until the 1970s that books considering the art of David in terms of the political and social context of the Revolution began to appear in English.55 For whatever reason, Antal chose not to develop his ideas in a major book. Instead, his articles relied on a few key works which allowed him to cover a substantial and complex period in relatively short texts while also suggesting some of the deeper issues at stake.

Antal’s analysis depends on a view of the French Revolution and its aftermath as one of political confusion from which the bourgeoisie emerged as the dominant class establishing a full capitalist mode of production. Although there is now considerable debate among economic historians as to whether the Empire and Restoration periods did indeed mark the arrival of a mercantile bourgeois economy in France, there was little question over this, even among right-wing scholars, until the later twentieth century. Nowadays, scholars prefer to bring forward the date of full political and economic emancipation of the bourgeoisie to the July Monarchy, but there can be little doubt that the Revolution and its aftermath saw the emergence of a bourgeois consciousness and world view which led directly to the entrepreneurial culture characteristic of capitalism.56 In any case, Antal appreciated that such fundamental changes in socio-economic relations had not been a simple or straightforward process. While sensitive to the complex allegiances, he wanted to reveal the deep shifts or breaks in French painting during this 35-year period.

To navigate his way through the divergent tendencies of the post-revolutionary period Antal fixed on Gericault, ‘the greatest French artist of the early nineteenth century’57, seeing in his response to different political and artistic developments a struggle to develop an art that expressed the new values of the age. As one might expect, the world view or consciousness that Antal was trying to uncover was that of various sections in the bourgeoisie whose fortunes had undergone a series of dramatic advances and reversals in the space of just one generation. Rejecting successively the later classicism of David, the emotionalism of ‘Romantiques’ such as Girodet, and the ‘Rubenisme’ of Gros, Gericault’s late work is seen to approach a type of naturalism that introduces the major issues that will come to dominate French painting for most of the century. In addition, Gericault’s work is shown to represent a new ‘democratising’ principle that rejects both the hierarchy of genres and the hierarchy of media that relegated genre painting and printmaking to an inferior status. This was a bold reading of French ‘Romantic’ art at the time, and the implications, albeit outlined with a broad brush, have never been developed. Many scholars had been struck by the stylistic diversity that characterised the Directoire and Empire, but their interpretations were based almost exclusively on the relationship between formal characteristics and academic theory.58 Antal’s reading of the period posited a new set of criteria for interpreting the ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’ tendencies, passing over pictures that dominated the major books and galleries, and placing emphasis on works which had previously been regarded as minor or secondary. The Raft of the Medusa could not be ignored, but while it may have represented ‘the climax of one artistic current’, for Antal it also demonstrated the bankruptcy of state-sanctioned art forms and the ‘disintegration’ of a tradition that was being kept alive only by reactionary forces in the society.59 It is Gericault’s late works – portraits, landscapes, genre paintings and prints such as Entrance to the Adelphi Wharf of 1821 (Figure 8) – which reveal the new spirit in nineteenth-century art and which address problems of naturalism and realism that will engage artists during the next 60 or 70 years. By implication, Delacroix and Ingres are marginalised in this overview and their work is seen as a diversion from the larger currents of the age; and this despite the fact that Delacroix, in particular, was frequently regarded as the first of the Modernists.60 In fact, Antal closes his account with the observation that Gericault’s late pictures anticipate the work of Courbet, implying that it is only in 1848 that we see a return to the central issues of painting in the period of triumphant capitalism. Antal was too serious a historian to regard Gericault as somehow ‘ahead of his time’, but the ability to project the true consciousness of the emerging class is no less than Antal would have expected of a major artist.

Hogarth and His Place in European Art should have been the clearest, if not the definitive, expression of Antal’s larger views on the social history of art, although the status of this book remains uncertain.61 Hogarth has always been highly regarded in Britain and there has rarely been a period when he lacked serious or popular interest. In fact, he has been afforded at least one major publication and reassessment by every generation since the late eighteenth century. It is somewhat remarkable, therefore, that a Hungarian Marxist, for whom English was always a second (or, more accurately, a third or fourth) language, should be the first to interpret Hogarth’s work as the manifestation of a particular set of ideals and values characteristic of the middle classes in the period of emerging capitalism, rather than a vague notion of ‘Englishness’. This was, of course, the principal reason for Antal’s interest. Hogarth, as Antal states, ‘gave complete expression to the outlook of the age, perhaps the most heroic phase of the middle class in England, and Hogarth’s was the most pronouncedly middle-class art that England ever produced’.62 His work, therefore, is a mediation of the ‘utilitarian, common-sense’ values of his class, their ‘world of ideas’ and their ‘slightly sentimental appeal to virtue and industry’.63 As in his previous writings, Antal saw class allegiance expressed through style, but this led him to some complex and questionable descriptive terminology when addressing British art of the eighteenth century. Hogarth was extremely eclectic with regard to his sources and Antal believed this was traceable to different allegiances in the class pattern of British society. This, after all, could be said to reflect the interpenetration of the classes at a time of relatively peaceful transition. There was no question that Hogarth was working in a period of fundamental change in the economic and political structure of Britain and that he, more than any other artist of the period, makes those changes explicit in his art. Stylistic analysis of Hogarth’s work, however, gives rise to some cumbersome descriptive labels, such as ‘rococo realism’, which Antal regarded as the English middle-class version of a French aristocratic style. Reynolds’s work is seen as ‘Baroque’, while Hogarth’s art is felt to have ‘assumed in varying degrees mannerist, baroque, rococo and even classicising features’.64 This made Antal’s book vulnerable to criticism from a new generation of empiricist scholars, such as Francis Haskell,65 but it might be explained as the legacy of Riegl and Dvořák who had upheld the priority of stylistic analysis as the key to art historical interpretation. Antal’s continuing adherence to these principles, or at least his attempts to make a link between the Marxist ‘social history of art’ and the basic tenets of the Vienna School, point to the gradual development of his methodology rather than any sudden adoption of new techniques. It also suggests that Antal was loathe to abandon the fundamental techniques of the Vienna School, especially since they had not been applied systematically to British art.

Antal’s Hogarth had a curious double effect, emphasising the artist’s international range while re-establishing him as a central figure in British culture of the eighteenth century. Thus Antal set Hogarth alongside Defoe, Addison and Fielding as a representative of the emerging mercantile middle class, as opposed to his traditional title as ‘father of English art’, which previous biographers had offered.66 But Antal was also prepared to place Hogarth at the forefront of European art and to claim, somewhat controversially, that English art was the most progressive and innovative in Europe before the French Revolution. There is more than a hint of economic determinism here – the most advanced economic and social structure must, of necessity, support the most progressive art – but Antal measured his assessment to describe the specific characteristics that were introduced by Hogarth and his generation. ‘Only in England and only during those years could an art have developed with so intensely didactic, utilitarian and moral a purpose and so vigorously combative a spirit.’67 In this sense, the book might be seen as part of a new phase in the scholarship of British art which had been gathering pace since 1933 when European scholars began arriving in London. British art had been largely ignored by continental art historians and there were no significant studies of any British painters or movements by the early pioneers of the discipline. As one might have expected, this began to change when figures like Edgar Wind, Rudolf Wittkower and Nikolaus Pevsner turned their attention to the material at hand in British galleries and libraries. The first sign of a new and more rigorous approach can be seen in Wind’s article ‘The Revolution in History Painting’ of 1939, which highlighted important changes to a traditional academic category at the hands of Anglo-American painters in the late eighteenth century.68 Not only did this raise the profile of artists such as Benjamin West, John Singleton Copley and James Barry, it demonstrated the extent to which British art was linked to wider European currents and that these were often influenced by innovations from within Britain. This was followed after the war by Ellis Waterhouse’s ‘The British Contribution to the Neoclassical style in Painting’ (1954)69, and The Art of William Blake by Anthony Blunt (1959), perhaps the first monograph on a British artist in the new art-historical manner. Antal’s books on both Hogarth and Fuseli were part of this general tendency, although there was a delay owing to Antal’s death, which held up their publication.

Antal’s unequivocal position as a Marxist, in political outlook as well as in methods of scholarship, may explain why he never gained any position in a British university.70 He did not lack for admirers, however, and several of the most important and influential figures in British art history and criticism looked to him for leadership. A measure of Antal’s appeal in Britain might be taken from the fact that he seems to have impressed scholars from widely differing political and methodological camps. On the right, if one can use the term here, John Pope-Hennessy saw in Antal a historian who had undertaken a fundamental review of the discipline of art history and prepared the way for a major reassessment of the great periods at the heart of the canon,71 while, from the opposite end of the spectrum, John Berger was similarly drawn to Antal, as much for his personal qualities as his intellectual rigour:

One would probably have said, despite the fact that his presence straightaway shamed one out of any romanticism, that he was either a poet or a political leader. When I used to go and see him and tell him of my week’s activities, I felt like a messenger reporting to a general.72

The most important channel of influence was through Anthony Blunt, who made his debt to Antal clear in the short memoir published in 1973.73 Blunt begins with a self-mocking account of his own early interests which serves to indicate how amateurish and narrow most writing on art was in Britain during the 1920s and early 1930s. This was, of course, before the sudden influx of German and Central European scholars who arrived in Britain as a result of the rise of fascism in Germany. Discussing his early engagement with socialist ideas and his attempts to link this to his other interests, Blunt wrote:

In art history we were of course also influenced by people outside. There were not very many Marxist art historians at that time. There was Friedrich Antal who had come from Germany in 1934 [actually 1933], and had settled in London, and who had not at that time written very much but had formulated a completed Marxist doctrine which he would expound at great length verbally.74

Blunt confirms the decisive role Antal’s ideas played in his own intellectual development when he reports how he and his contemporaries began to re-evaluate the art of the past and, more especially, their individual tastes and preferences ‘according to the gospel of St Antal’. What is clear is that Blunt adopted many of Antal’s methods and assumptions, in particular the identification of ‘naturalism’ and ‘rationalism’ with the tastes and aspirations of the emerging bourgeoisie. ‘Giotto and Masaccio in Florence, Michelangelo and Raphael in Rome, Poussin in France and Rembrandt in Holland represented the progressive stages in the development of the bourgeoisie’, whereas, ‘[w]e thought the Impressionists had deserted the true line opened up by Courbet and that their art was limited to an interest in purely optical effects’.75

This memoir, prepared originally as an informal lecture for students at the Courtauld Institute, is necessarily brief and simple but there are other indicators of Antal’s influence on Blunt’s early writings, and most notably in Artistic Theory in Italy 1450–1600.76 Blunt was closest to Antal during the preparation of this short survey, and his selection of theorists as well as the gloss he places on their work reveals again the underlying assumption that art theories, like the artists and writers who prepare them, reflect the political atmosphere and economic conditions of the society. This is perhaps most explicit in his discussion of Alberti, whose ‘rationalist’ theories on art, Blunt writes, emerge from the liberal, bourgeois environment of fifteenth-century Italian city states, as opposed to the ‘mystical’ ideas of the Neo-Platonists in Lorenzo de Medici’s more princely court in the later years of the century.77 Blunt’s artistic and scholarly interests moved on from here, mainly under the influence of Rudolf Wittkower, who replaced Antal as his intellectual mentor and encouraged his work on French and Italian art and architecture of the seventeenth century.78 Nevertheless, Blunt never abandoned a belief in the determining relationship between the socio-economic conditions of a period and the artefacts produced in it.79

Blunt’s position as Antal’s follower or ‘pupil’ was taken up by John Berger, the art critic and author who probably did more than anyone else in Britain to popularise a form of art history and art appreciation informed by modern theories of culture and political engagement. In an obituary written for the Burlington Magazine, Berger described Antal as ‘the logical, precise, profound art historian’, going on to suggest that ‘in any assessment of his work the importance of his Marxism tends to be underestimated’.80 In this, Berger seems to be addressing an issue that characterised several of the views expressed about Antal from conservative scholars hostile to his approach. Where Hauser and his work were sometimes attacked by British academics as excessively crude and simplistic, Antal presented a more formidable opponent. Not only was Antal’s work felt to be more sophisticated in method; his specialist articles indicated considerable breadth of experience in primary research. As a result, some of the tributes after Antal’s death emphasised his skill in visual analysis, while avoiding the Marxist basis of his work. Even Gombrich, who was implacably opposed to the social history of art in any form, conceded that ‘he had a good eye’.81

Berger’s reassertion of Antal’s political position had not been necessary when the main books were being reviewed in the scholarly journals. Here, Antal’s Marxism and the prominent place he gave to questions of methodology were generally the main points of argument and this would continue throughout the frostiest period of the Cold War as his posthumous works appeared in print. The tone was set by H. D. Gronau’s 1949 review of Florentine Painting and its Social Background. Gronau, a noted scholar in the field, praises Antal for the intellectual breadth and ambition of the book and for the mass of assembled facts which affect our understanding of many early Renaissance art works, but at the same time deplores how ‘Dr. Antal directs his researches into the narrow channels of class-conscious dialectics, which confuse and disappoint to an extent that makes objective criticism a difficult and irritating task’.82 The same theme is apparent in Millard Meiss’s review of the book, where the ‘difficulties’ are traced to Antal’s ‘social determinism and other assumptions of his orthodox Marxist point of view’.83 That this debate rapidly became a touchstone for analyses of fourteenth-century Italian art was evident when Meiss published a book on the same territory two years later claiming to offer a different reading of the main developments and their causes.84 Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death proved to be an influential text for the next generation of art historians, but this was largely because Meiss attributed the political and economic turmoil of the middle decades of the fourteenth century to the effects of the plague alone rather than as part of a larger pattern of shifting socio-economic relations. By proposing a single cause to a complex set of factors, and by largely ignoring issues of class in Tuscan society, Meiss’s book may have been more accessible to students, but even sympathetic reviewers recognised that this was an oversimplification of the issues. In addition, much of the evidence Meiss used to support his thesis has since been discredited, although this has not undermined the book’s popularity as an undergraduate text.85

For Francis Haskell, reviewing Hogarth and His Place in European Art, the problems did not lie with an attempted social history of art, which he felt was simultaneously ‘inspiring’86 and ‘a wonderful relief after the vague and unsubstantiated generalizations of other writers’,87 but that Antal’s assumed link between class interests and style was ‘dogmatic and over-simplified’ or even circular in argument. Haskell takes this point further in suggesting that Antal’s larger aims of setting the work of art in its historical context had been pursued by the generation after Antal, but that they had ‘not on the whole done so in the manner that he followed in his own studies’.88 Haskell himself could be described as a practitioner of the ‘social history of art’, in its broadest sense, and the general term was extended to several other figures who emerged from the Warburg Institute.89 The notion that a ‘British school’ of the social history of art grew up in the generation after Antal seems to have had some currency, particularly in the United States.90 But any attempt to establish a common ground between the work of Haskell, Baxandall and T. J. Clark is destined to remain at a very superficial level. For neither Haskell nor Baxandall was the issue of social division – of class antagonism and class struggle – the fundamental motor of change in history. Baxandall, in particular, partly because he addressed problems close to those in Antal’s writings, seemed to represent a revised or refined form of social history of art – one with rigorously defined parameters but drained of any political reading of history.91

Among the historians on the New Left, Antal’s work prompted divergent responses. In Art History and Class Struggle, first published in France in 1973, Nicos Hadjinicolaou invoked Antal as the model for a ‘committed’ art history ‘based on historical materialism’.92 In fact, Hadjinicolaou suggested that his book was a reworking, or ‘reappraisal’, of a lost pre-war tradition exemplified by Antal, Klingender and Meyer Schapiro. Far from being a victim of ‘short collective memory’, however, Antal’s work was still sufficiently familiar to left-wing art historians to raise questions about Hadjinicolaou’s concept of artistic style and the ways in which it might exemplify meaning in a context of wider class relations.93 In particular, Hadjinicolaou’s term ‘visual ideology’ was attacked as an excessively rigid concept that collapsed many of the distinctions between formal characteristics, content and social ideology. This may have been derived from Antal’s expansion of stylistic analysis to embrace style, subject matter and class-consciousness but, if so, it represented a reductionist view that was not likely to invigorate the earlier tradition.

T. J. Clark’s relation to Antal’s pioneering work is equally problematic. The two books from 1973 on the work of Gustave Courbet in the context of French politics of the mid nineteenth century94 might have been expected to develop the interests Antal had addressed in ‘Reflections on Classicism and Romanticism’. In fact, they marked a new point of departure for the social history of art in Britain. Clark cites Antal’s work but states quite clearly in the opening chapter of Image of the People that what he is aiming to do is quite different from earlier historians. ‘I am not interested in the notion of works of art “reflecting ideologies, social relations or history”’, he writes, and ‘I do not want the social history of art to depend on intuitive analogies between form and ideological content’.95 This suggests that, by the 1970s, the pre-war generation was perceived as practising an outmoded and possibly failed version of Marxist art history. Even Antal’s work, which was widely felt to represent the best of its type, was ill-equipped to meet the criteria of new forms of art history informed by feminism, semiotics, structuralism and post-structuralism.

There is no mention of Antal in recent books on historiography and methodology.96 In North America, where his views generated considerable controversy, he seems to have been forgotten, and in Hungary he is little known, if at all.97 Even in Britain, one seldom encounters references to Antal in publications or university courses that cover either the periods in which he specialised or the methodological problems that he addressed. Antal himself was clear about the historical contingency of art-historical method: ‘Methods of art history, just as pictures, can be dated. This is by no means a depreciation of pictures or methods – just a banal historical statement.’98 Nevertheless, the problems Antal addressed are still with us. They have not been solved, nor have they gone away. It is the socio-economic background material that has expanded exponentially since his death, not the detailed art historical analyses, which he had both advocated and practised. Antal remains one of very few art historians to have taken up such issues consistently and across a broad spectrum without compromising either his political ideals or standards of scholarship.