4

Art as Social Consciousness: Francis Klingender and British Art

The work of Francis Donald Klingender (1907–55) lives on in a small number of theoretical essays,1 and mainly in Hogarth and English Caricature (1944) and Art and the Industrial Revolution (1947). These books still remain compelling though inevitably much has happened in the more than 50 years since their publication to elaborate and question their methods and conclusions. Klingender anticipates the concern of more recent art historians with artists responsive to social and political change and in the ongoing debate over the nature of ‘popular art’, though in neither case has his pioneering role been fully acknowledged. In Hogarth and English Caricature he opened up English satirical prints for serious art-historical study rather than just as illustrations of political events, as well as even more neglected forms of visual expression, such as popular broadsides and woodcuts, transfer-printed pottery, mechanical drawings and money tokens. While he did not invent the idea of popular art – that distinction belongs more to Champfleury in mid-nineteenth-century France, or perhaps even to Herder in the eighteenth century – he gave it a new theoretical and historical basis. It would be wrong, however, to think of the implications of Klingender’s work as only confined to British art. Apart from his books on Goya and on animals in art,2 in a number of essays he offered a strong materialist critique of the idealist tradition, represented in Britain in the period of Klingender’s intellectual formation in the 1920s and early 1930s by the formalist aesthetics of Clive Bell and Roger Fry.

Klingender came to England from Germany, where he was born, in 1925. He was neither a refugee nor German by nationality – he was British by birth – but he did have deep German connections through his father’s and mother’s families. His father was the well-known animal painter Louis Klingender (1861–1950), who was born and brought up in Liverpool, but studied painting in Düsseldorf under Carl Friedrich Deiker (1836–92) and made a career in Germany, exhibiting in Berlin and elsewhere.3 In 1902, Louis Klingender moved to Goslar in the Harz Mountains in central Germany, where he curated the small museum, which still prominently displays one of his paintings. The younger Klingender was born and went to school in Goslar. His father was interned briefly in Germany as an enemy alien and possible British spy at the outbreak of the First World War. He was evidently shunned by his former acquaintances in Goslar and reduced to near poverty,4 though he remained in Germany throughout the war.

The Harz was an important mining and industrial area in the nineteenth century, and, as Grant Pooke has pointed out, not wholly dissimilar to the English industrial areas that Klingender was to write about so eloquently in Art and the Industrial Revolution.5 The family returned to England after Francis’s school graduation in 1925, but his father had difficulty selling his by now unfashionably Victorian-looking paintings.6 After an initial period in an advertising agency, the youthful Klingender worked for a time at Arcos (All Russian Co-operative Society), the Soviet trading agency that shared premises with the USSR Trade Delegation, probably starting shortly after the notorious raid in May 1927, authorised by the Home Office on the suspicion that it was a nest of Soviet spies.7 Whatever effect working for Arcos had on his political beliefs, it is probable that he joined the Communist Party before 1930, during the time he attended evening classes at the London School of Economics. He graduated from the LSE in sociology in 1930, receiving his Ph.D. on the ‘the Black-Coated Worker in London’ in 1934, published the following year as The Condition of Clerical Labour in Britain by the communist publishing house of Martin Lawrence. This work was an investigation into a section of those who belonged to the ‘middle strata’, that is to say workers without capital who were nonetheless alienated from and fearful of the working class. Klingender argued that capitalism could only be overthrown if the middle strata and the working class were to unite in a common cause.8

Following the completion of his thesis, Klingender was occupied with a number of sociological research projects, which provided him with such income as he had in the 1930s. Klingender was not a trained art historian like his friend Frederick Antal, though art was at the heart of his academic interests, something that he later attributed to the influence of his father.9 His daily life was taken up with surveys of labour relations in the film industry and elsewhere, and his first and last permanent academic post, from 1948 until his death in 1955, was as lecturer in sociology at the University of Hull, where the communist historian John Saville was among his colleagues.10 Saville has noted that Klingender’s existence was always hand to mouth until he got the job at Hull.

Klingender’s practice as an art critic and theorist derived entirely from his membership of the Artists’ International Association, though he did not work for the organisation until 1943. It had been founded in 1933 as the Artists’ International by a group of Communist Party members, most of whom had direct experience of the art organisations of the USSR, and who wished to set up similar structures in Britain to contribute to the international struggle for socialism11. The AI was associated with such organisations as the British section of the Writers’ International and The Workers’ Music Association. Though Klingender was not a founder of the AI he was one of the first group of 32 members in 1934, and he gave ‘a series of twelve discussion-lectures on French and English nineteenth- and twentieth-century art’ to it in 1934–35.12 This is a matter of importance for assessing Klingender’s position, for in 1935 the AI changed its name and direction, becoming the Artists’ International Association, to ally itself with the People’s or Popular Front, enlisting intellectuals who were not party members but were anti-fascist and sympathetic to social change.

This transformation reflected larger political changes. At the First Soviet Writers’ Conference in August 1934, ostensibly on the Problems of Soviet Literature, Maxim Gorky had claimed that the fate of writers was linked ‘irrevocably with that of the proletariat’; they must be ‘consciously setting themselves the task of contributing by means of their literary works to the victory of socialist construction’. Writers were to be ‘engineers of human souls… standing with both feet firmly planted on the basis of real life’.13 In July 1935, however, a dramatic shift was initiated by the USSR in its relationship with the Communist Parties in other countries. The Seventh World Congress in Moscow, in response to Hitler’s assumption of power, proposed a strategy of ‘widening out’, to bring together all sympathisers in other countries, even those who were not party members or proletarians, into a common front against fascism.14 From 1935 onwards, the AIA redefined itself as primarily an anti-fascist organisation (in the words of its manifesto, ‘[t]he AIA stands for Unity of artists against Fascism and War and the Suppression of Culture’), drawing in a remarkable range of artists and thinkers who represented the whole range of artistic movements from abstraction to social realism, and the political opinions of Soviet-influenced Marxists like Klingender, anarchists like Herbert Read and Catholic radicals like Eric Gill.

The variety of viewpoints is exemplified in a collection of essays edited by Betty Rea and published in 1935, based on lectures given to the AIA, entitled 5 on Revolutionary Art, to which Klingender contributed. In Margot Heinemann’s words ‘it was a consciously and deliberately pluralist production’.15 The editor summed up the diversity of the contributors – and the AIA – at this point:

You may agree with Mr. Read, that art within the boundaries of form can have its own revolutionaries, or with Dr. Klingender and Mr [A.L.] Lloyd, who hold that art is part of, and inseparable from, the society in which it flourishes – or does not flourish. Perhaps you will feel as Mr. Gill does, that Catholicism might produce a form of the unanimous society which so plainly does not exist in our own time, and which is after all the thing all men desire and propagate, each according to his vision. Mr. [Alick] West writes of art in one new form of unanimous society – a socialist society so young that we cannot know what untraditional forms its art will take.

Klingender’s essay on ‘Content and Form in Art’16 shows him to have been the best-grounded of the contributors in Marxist theory and German art history.17 Unlike the others, his argument is not at all rooted in English experience; the brief history of recent art that he gives in the essay (presumably taken from his lecture notes) is firmly French and German in content, mentioning the English Futurists in passing, and the only theoretical referents are Marx and Engels. Even so, his idea of the necessary interrelationship of form and content was mainly directed against the primacy of the former over the latter, and against the rise of abstract art in England, which he and the other contributors to the collection, apart from Read, saw as mere formalism, an extension of nineteenth-century art for art’s sake. Klingender took a firm position that art was a form of social consciousness, belonging to specific groups of individuals and related to basic processes of social development.18 Art reflected ideologically the struggle between social man and nature, which required to be analysed with historical specificity according to the social group that produced the art and that group’s phase of development. These were themselves determined by the productive resources and forms of organisation embodied in a class structure. Art, however, was for Klingender more than just a reflection of social reality; it was a revolutionary agent for transformation, for it had always in history reacted visibly and spontaneously to changes in the relationship between new conditions and old forms of consciousness. It followed that art was not passive but an active expression of the outlook of the most progressive class in any given society, and it was wrong to see art, as did many Marxists,19 as having no possibilities beyond capitalist consumption, though that might be its predominant condition in present society.

Of the two given aspects of art, ‘form’ and ‘content’, the latter, Klingender argued, should not be defined reductively, as it was by formalists, as merely ‘subject matter’ that could be diminished or disregarded, but as the response of a social group to the material conditions of its existence that needed to be given convincing form in art. Form cannot exist free of content, but is the language in which content is expressed; it must necessarily be shaped by, and be as various as, content. Klingender thus explicitly rejected the domination of form over content, expressed succinctly in Clive Bell’s idea of ‘significant form’, rejecting also a single aesthetic scale in which abstraction is dominant. Nor was Klingender persuaded by the claim of some of his fellow authors in 5 on Revolutionary Art that true art cannot now be comprehensible to the proletariat, but must await such time as their false consciousness has been overcome by the triumph of socialism.

The pioneering nature of Klingender’s essay in the British context needs to be emphasised. There were other art historians in England by the mid-1930s who were Marxists, such as Frederick Antal and Anthony Blunt, but no one had previously published such a sophisticated Marxist theory of art in the English language. Having said that, Klingender’s broad argument is not especially original; it was in line with much recent Soviet and French thinking, and as a materialist theory of art it has clear origins in the work of G.V. Plekhanov (1856–1918), who wrote in 1895 the first full account of Marxism in Russian.20 The basis of Klingender’s central arguments can be found in Plekhanov’s writings, which may be summarised as follows: ‘literature and art in their origin and development can only be truly understood in the light of the materialist conception of history’;21 ‘art for art’s sake’, or formalism, is based on philosophical idealism and is by definition bourgeois art, in polar opposition to utilitarian art that reproduces and explains life; it is the critic’s role to analyse the relationship between the mode of life and art on the understanding that the creation and appreciation of art are dependent on the artist’s and public’s position in relation to the current class struggle; artists or writers are only progressive when their work is based in the class that is leading society forward: in the present age, of course, the proletariat.

By 1935, not much of Plekhanov had been translated into English, and Art and Social Life (1912), the work in which the role of the artist, author and critic are most clearly articulated, did not appear in translation until two years later.22 Klingender would certainly have known Ralph Fox’s translation of Plekhanov’s Essays on the History of Materialism, published in 1934,23 but that is not concerned with art or literature and is a series of essays demonstrating Marx’s place in the history of philosophical rationalism. He might have known Art and Social Life through a German edition, or perhaps at second hand through Antal, or he might have picked up enough Russian to read it from working at Arcos.

Despite his contribution to 5 on Revolutionary Art, Klingender was not a regular contributor to Left Review. One reason is clear from his attack in the October 1935 issue on one of the editors, Montague Slater, for praising an exhibition by the Soviet sculptor Dimitri Tsapline. Slater writes enthusiastically about what he admits were ‘small statues [of animals] suitable for art galleries’, reserving particular praise for a drilling workman and for his ‘Soldier’s Head’ with Red Army helmet, which ‘seem to belong to the stone just as much as his animal masterpiece which tells us none of the details but all the facts about a crouching lion’.24 Klingender responded sharply by arguing that such sculpture was essentially bourgeois in its form despite its proletarian content: ‘Remove the Soviet Star from the helmet of the “Red Soldier”’ and he would resemble pompous German monuments to Bismarck: ‘would any worker wielding a pneumatic drill eight hours a day feel the spark of personal experience if confronted with the cubist romanticism of Tsapline’s “Workman”?’ Tsapline’s long period of study in Paris had severed his roots from the mother soil of vital experience and led him to succumb to bourgeois influences. The artist needs to learn that ‘[a]rt can face the facts of social reality and point towards a method of their solution, or it can hide them and provide an escape from them.’25

Klingender attacked not only the artist but the critic for his lack of rigour: ‘Marxian analysis… can and must prepare the artist for this achievement by tearing him out of the dreamland of abstraction and bringing him face to face with his problem.’ It follows that ‘a revolutionary critic can only judge the content of art by the profundity of its social experience and its form by the degree to which it succeeds in transmitting the inspiring message of that experience to the working class and its allies’. This remorseless critique provoked a reply not from Slater but from Ralph Fox in the November issue, under the heading ‘Abyssinian Methods’. Calling him ‘Colonel Blimp-Klingender’, Fox accuses Klingender of a patronising attitude towards Tsapline, and applying ‘only one standard for the assessment of any ideological phenomenon…its relevance in terms of social reality’.26

Fox’s bad-tempered, even sneering response to Klingender’s cogent points reveals a fault line in English Marxist aesthetics in the mid-1930s between those like Klingender and Anthony Blunt, who were essentially international in experience and outlook, and those like Fox, A.L. Lloyd and A.L. Morton, who were increasingly concerned to reclaim an English past that would show socialism as the culmination of historical advance and the resolution of past national struggles. In Heinemann’s words, the ‘Seventh Congress helped the left to reclaim patriotism and British freedoms’.27 The AIA in the late 1930s was much involved in the English road to socialism, widening definitions of culture to include ‘Merry England’: games, dancing and popular songs. Marxist historians wrote on the English revolution and, in 1938, the Left Book Club published A.L. Morton’s The People’s History of England.28 Klingender, with his philosophical rigour and his continental background and Blunt, with his affinities with France, were wary of the general retreat from internationalism among the English left. Klingender seems to have devoted his intellectual energies in the late 1930s to Goya, though his book was not published until after the war.29

Klingender seems to have been left cold by contemporary Soviet socialist realism; there are hints that his sympathies were more with the avant-garde artists of 1917, despite his theoretical rejection of abstract art.30 The artist who came closest to his ideal for the time was Peter Peri, whose early career as a Hungarian constructivist and his conversion to realist figure sculptures in concrete made him an artist who used new techniques to express the vital experience of ordinary people. Peri was also championed by Blunt, who had invited Klingender to lecture in Cambridge, and was increasingly drawn to the AIA in the mid-1930s, giving a lecture entitled ‘Is Art Propaganda?’ for the organisation in April 1936.31 Klingender was probably also drawn to the caricatures of the ‘Three Jameses’, Boswell, Fitton and Holland, who consciously followed in the English caricature tradition, though in reality George Grosz was a major influence on their work, especially Boswell’s.32

The year 1943 was a critical one for Klingender, for he was put in charge of the AIA’s new Charlotte Street centre, which allowed him to put on exhibitions that were to be seminal for his later historical work. He also published his most substantial work of theory, his pamphlet Marxism and Modern Art of 1943, subtitled An Approach to Social Realism.33 It represents an enrichment and deepening of the materialist basis of his 1935 essay on ‘Content and Form in Art’, but it also moves in a new direction, towards a more profound concern with English art and history. Rather than simply attacking abstraction in Plekhanov’s terms, he now makes more specific his objections to Fry’s notion, elaborated in the 1920s and beyond, of a pure painting ‘free abstract and universal’. This, he argues, is tainted by the desire to reduce the response to art to one single aesthetic feeling; thereby divorcing art from life and moral questions, mystifying the aesthetic and reducing the public for art to a select and self-regarding minority.34 Klingender cites Fry’s remark in Vision and Design of 1920: ‘in proportion as art becomes purer, the number of people to whom it appeals gets less’.35

Fry, however, was not, as Klingender well knew, simply a reactionary, nor was he operating in an intellectual vacuum. He was, among other things, trying to reinvigorate the idea, an essential principle of art academies since the Renaissance, that the imitation of nature in art was secondary to, or an instrument of, art’s ‘higher’ moral and aesthetic purposes. In the earlier part of the twentieth century, Fry increasingly involved himself in post-Kantian metaphysical aesthetics, in which art exists on a plane above the mundane world and could be a refuge from it – a position still restated to this day by museum directors. Fry himself admitted to embarrassment at the ‘mystical’ tendency of his thought,36 and Klingender astutely connects his retreat into other-worldly aesthetic theories with the widespread disillusionment caused by the horrors of the First World War.

Fry’s aesthetics were worth combating precisely because of their claim to radicalism. Rather than being attached exclusively to Antiquity, the Italian Renaissance or the Middle Ages, they were applied to near-contemporary artists, like Cézanne and Gauguin, who were, in England if nowhere else, still regarded as avant-garde. As Klingender sarcastically put it, Fry’s interest lay in ‘the tame still-lives and the harmless holiday scenes of the post-impressionists’, who had become ‘increasingly preoccupied with the technique of art, to the neglect of its content’, and whose followers ‘completed their escape from reality into the arid desert of pure form and the various other brands of neo-mysticism’.37 For Klingender, art’s essence is and always has been materialist; it is, therefore, in permanent opposition to the equally tenacious tradition of ‘spiritualistic, religious or idealistic art’, of the kind supposedly favoured by Fry and his acolytes. An art that was to express ‘the interests and aspirations of the people’ required nothing short of a ‘resolute rejection of all forms of philosophical idealism and mysticism’. As Harrison and Wood have noted, such a binary view of art as always involved in a conflict between a progressive realism and a reactionary idealism goes back to ‘Lenin’s claim that history itself embodies at each moment a struggle between two tendencies: the one ultimately progressive, the other reactionary’.38 In fact it goes even further back, to Plekhanov and perhaps to Marx. Klingender argues that nonetheless human understanding could progress, and in the past had progressed, within the frameworks of reactionary systems of thought.

Such an uncompromisingly materialist position might have led Klingender towards aesthetic relativism, a belief that different periods and styles should all be studied as if they were of equal value. But he argues that Marx himself rejected such relativism in describing the decline of art under capitalism, on the grounds that any choice of objects to be studied will betray the historian’s preferences or prejudices, and such a choice must inevitably be conditioned by the standards of the time and by class. Hence, as Klingender put it, in an aesthetic relativist position ‘the problem of aesthetics proper, i.e. the problem of value, is evaded’.39 Aesthetic relativism can only lead to the shallow and reductive conclusion, espoused by ‘vulgarisers of Marxism’, that the ‘art of the past has always expressed the interests of an exploiting class’. If that were so the classics would have faded away with the advance of socialism, which they manifestly have not, and should not. Klingender argues that, on the contrary, artists are special beings who consciously or unconsciously travel mentally beyond the confines of their class to be abreast of the most advanced tendencies of their time. They are affected by wider historical movements, like the rise of empire or the Industrial Revolution, which might be invisible from the perspective of one class. Works of art are inevitably bound by their time and their makers’ class, but they can also retain for later generations an intimation of what Lenin called the ‘absolute’, a truth that can be transmitted across time from one age to another, and which illuminates the deeper movements of history. As in philosophy, so in art; hence ‘there is not a single style in the history of art which has not produced some concrete advances towards the absolute’.40 Thus Tolstoy, as Lenin pointed out, could express with accuracy and brilliance the crisis among the Russian masses in his own time without necessarily consciously being in sympathy with their desires. Artists, for their part, could work within styles that might overtly proclaim absolutist or theological values, yet their implicit or unconscious resistance to them can still be visible to later generations and be what keeps them alive beyond their own time.

Klingender espouses a surprisingly wide conception of realism, despite his rejection of all forms of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and his lack of interest in the seemingly value-free ‘objectivity’ of the Euston Road School. His idea of realism was not tied to one style or another; it encompassed art’s origins in Paleolithic cave paintings and ‘the productive intercourse between man and nature which is the basis of life’. The binary opposition between progressive and reactionary types of art was itself a product of the division between mental and material labour that ‘will vanish with the final negation of the division of labour – i.e. in a Communist world’. The history of art has, therefore, always been a struggle between these traditions, which will ultimately end in the triumph of materialism in the final resolution of the political dialectic. The Marxist art historian’s job in the meantime is to discover ‘the specific weight within each style, each artist and each single work of those elements which reflect objective truth in powerful and convincing imagery’, on the understanding that they will not yet be able to throw off elements of the metaphysical style of their age, just as Hogarth could not throw off all traces of the ‘absolutist’ Baroque of his own age, nor the builders of cathedrals the religious framework of the Middle Ages. Klingender argued that realism was ‘from its very nature popular’, because it ‘reflects the outlook of those men and women who produce the means of life’. In the end it is their idea of art that matters, and it is they who, to quote William Morris, as Klingender does in the conclusion to his pamphlet, will regain ‘the sense of outward beauty’ when they are liberated from the alienation of capitalist society.41

Klingender cites the authority of Marx and Lenin extensively in this 1943 pamphlet, but it is significant that he should end it with an extended quotation from Morris. With Britain and the Soviet Union now allies against fascism in the years after Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Marxists could feel comfortable in invoking Soviet texts while extolling and encouraging British patriotism, as Klingender does in his short book Hogarth and English Caricature of the following year, and in an exhibition of caricatures at the AIA, which makes a parallel between the current wartime alliance with the Soviet Union and the early nineteenth-century alliance between Britain and Russia against Napoleon. Hogarth had been an important reference point for the social-realist artists of the AIA from the beginning; the Communist Party artists had called themselves the Hogarth Group, and Laurence Gowing described Hogarth as ‘the ideal of the socially conscious British artist’.42 The ‘Three Jameses’ also saw themselves as working in the tradition of Hogarth.

Klingender’s Hogarth volume began life as the catalogue of an exhibition at the Charlotte Street Centre in London, largely based on Klingender’s own and Millicent Rose’s collection, now in the Prints and Drawings Department of the British Museum.43 The text is only ten pages long (there are also illuminating captions to the illustrations), reducing his remarks to a series of aphorisms, yet it covers an astonishing span from the Middle Ages to his own time. Hogarth is the pivot of the argument, though it introduces among others almost totally unknown caricaturists like Richard Newton and C.J. Grant (Figures 9 and 10), and the radical token maker Thomas Spence, all of whom have attracted renewed attention, although only in recent years.44

Klingender deliberately confined his attention to prints rather than paintings or sculptures, which in earlier ages generally could only be seen by the elite. ‘Based as they were on a popular market and depending on a large turnover, these prints reflected what was uppermost in the public mind’, he wrote. The popularity in the full sense of prints in earlier centuries was evident from the huge volume of designs that were etched or engraved on copper and the great number of impressions taken from them that have survived to the present day. They were available to Klingender in the great collections in the British Museum, but he could also buy them for a few pence each on street stalls, like that of E.C. Kersley in the old Caledonian Market, mentioned so warmly by Arthur Elton in the acknowledgements to his revision of Klingender’s Art and the Industrial Revolution.45

The production of genuinely popular caricatures was, so Klingender believed, a distinctively English phenomenon that flourished particularly in the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century, and which grew under the paternal influence of Hogarth. Hogarth’s interest in real-life satire was a response to specific social conditions that enabled him to plug into ‘an undercurrent of popular satire’,46 that had persisted in medieval ornament in Europe even before it entered into the common culture through the invention of printing and printmaking in the fifteenth century. In the eighteenth century popular art flourished not only in caricature, but also in popular chapbooks and broadsheets, available to those who lived in London and in smaller towns and in the country.

For Klingender, this popular art was based on a common inheritance of storytelling and fantastic symbolism, hence it was not confined to a ‘realist’ artistic language. He compares Hogarth with the earlier Netherlands artists Hieronymus Bosch and Peter Bruegel, who had tapped into streams of fantasy as well as realism in the time of the first great national liberation struggle, the Reformation. Though Hogarth was a natural realist who faced contemporary life ‘fairly and squarely’, he was schooled in the period of the ascendancy of the illusionistic and absolutist style of the Baroque, which had a limiting effect on his prints. This is evident when they are compared to the more open and material space of Gillray’s prints, ‘which ‘transplant… us, bodily, into the surging stream of life itself, bathing us in its scintillating atmosphere’.47

For Klingender, Hogarth, along with his friend the novelist Henry Fielding, represented ‘the progressive elements in that society’, the kinds of people who were subsequently to be responsible for ‘the greatest technical revolution since neolithic times: scientific farming and machine production’. Hogarth was notable for the range of life he surveyed and his ability to see the weaknesses of his own class. Klingender ties changes in the style and content of caricature subsequent to Hogarth to the political changes of the day, noting its rich exuberance, diversity of expression, and reach into all aspects of English life, attaining ‘a unity of style which we today can only envy’.48

Eighteenth-century caricature is thus given an urgency as a model for current practice and aspiration. In only a few pages of text Klingender gives coherence to the immense production of satires in the eighteenth century, singling out the names of such then unconsidered artists as the ‘brilliantly gifted’ Richard Newton, and giving a wonderful thumbnail sketch of ‘the sardonic Gillray, remorseless and fiercely partisan, living in obscurity with his aged publisher Mistress Humphrey until his mind was deranged by the contradictions he so penetratingly disclosed, yet could not resolve.’

How does Klingender’s view of Hogarth and English satire look now? It is inevitable that the brevity of the text and the passage of time make it now look oversimplified. While it is possible still to see Hogarth as a representative of the newly emergent professional classes, his satirical narratives, the Rake’s and Harlot’s Progresses, and Marriage a-la-Mode, are surely less progressive than Klingender claimed. While Hogarth perhaps was clear-sighted about the weaknesses of his own class, he was in most respects politically conservative, working in his moral series to uphold the social hierarchies of the day.49 Hogarth’s attack on the vices of the different classes, much as one would like to believe otherwise, is not weighted on the side of that abstraction ‘the people’, as Klingender suggests, but, on the contrary, his prints were designed to encourage all people from aristocrat to labourer to live up to the ideals of their own class. He satirises not class per se, but those who try to move for selfish motives from the one to which they belong. In Industry and Idleness the obvious (and absurdly unlikely) conclusion from the narrative is that every apprentice has it in his power, by working hard and marrying the owner’s daughter, to become the owner of a workshop himself, and even to aspire to become Lord Mayor of London. Though Ronald Paulson has claimed that ‘Hogarth embraced both apprentices [i.e. the Idle and Industrious apprentices], both value systems’ they represented,50 it is hard to see the series as anything other than an instrument of social control, to be put up in workshops as a warning to unruly apprentices. Far from being perceived as a threat to the social hierarchy of the time, Hogarth was on good terms with merchants and dukes, who bought his satirical work avidly. In his last years he was himself the butt of satire by more authentic radicals like John Wilkes for his support of the government and his desire for courtly favour. On the other hand Klingender might have answered, as he did with Tolstoy, that Hogarth reveals facets of his own society against the grain of the public attitudes expressed in his art, as artists have done throughout the ages.

An association between realism and political progress is essential to Klingender’s theory, but it can be argued that realism, even in Klingender’s wide definition, did not always prove itself to be progressive. Many of the eighteenth-century satirists Klingender most admired, Gillray above all, were employed willingly as instruments of government propaganda;51 indeed, it was the government rather than the opposition that more often employed or paid off visual satirists. It is true that Gillray had a reputation as a closet supporter of the French Revolution, and Richard Newton and Thomas Spence were passionately radical (the latter was recognised by Engels as a forerunner of socialism through his plan for the division of land), but nothing exceeds the ferocity and relish with which Gillray (himself the recipient of a pension from the Pitt government) attributed bestiality and opportunism to the French revolutionary sans-culottes. It is now clear that, despite their apparent vulgarity – their relish in exaggerating personal deformities, and frequent representation of shitting, farting and pissing –caricatures were as much part of the fashionable world as the paintings of Gainsborough or Reynolds. There was furthermore a clear hierarchy of value among caricaturists themselves, with Gillray and Rowlandson at the top, selling to the West End crowd and the tiny number of people directly involved in political life, while lower down the social scale were the cheap productions of William Dent and the broadsheets of Seven Dials.52

The ‘Englishness’ of Klingender’s Hogarth contrasts interestingly with the contribution on the same artist of his friend and fellow Marxist, the widely travelled Hungarian émigré Frederick Antal. In Antal’s Hogarth and His Place in European Art,53 Hogarth, as the title suggests, is explained in terms of the response of painters to the progress of the bourgeoisie across the whole of Europe. Hence it is possible to find even in Venice artists like Pietro Longhi (1702–86) who share something of Hogarth’s social vision and sharp dissection of genteel customs. Klingender, on the other hand, argues that two streams run through Hogarth and English caricature, one coming from the Netherlands and the other, evidently wholly indigenous, running through ‘the simple woodcuts of the English chapbooks’, which in turn relate back to medieval marginal illumination and misericords. Hogarth might have had some knowledge of comic prints after Pieter Bruegel, but the main traditions of popular prints were, as Klingender well knew, as much German in origin as Netherlandish or English. But of course the state of war with Germany in 1943 would not have encouraged such a recognition, nor would his nostalgia for the pre-industrial England of the eighteenth century, which provided ‘the essential basis for popular art, a common civilization expressing the moods and aspirations and the way of life of the broad masses of people’, and which he now, as the final thought of the book, claimed at the height of an anti-fascist war was again ‘only … beginning to emerge’.54

Klingender’s most extensive and substantial work on British art, Art and the Industrial Revolution, published in 1947, started from an AIA exhibition in 1945 suggested by the Amalgamated Engineering Union, on The Engineer in British Life.55 It is altogether more reflective and wide ranging than Hogarth and English Caricature, though readers should be warned that the posthumous 1968 edition, edited by Arthur Elton and widely available in paperback, is quite different from the original 1947 edition, with interpolations, omissions and corrections by Elton that are only occasionally signalled and at times interfere with the argument.56 True to Klingender’s belief that artists necessarily engage actively with the great historical movements of their time, which for the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries he saw to be the Industrial Revolution and the consequent triumph of Victorian capitalism, he offers a new artistic canon, based not on London but on the original industrial areas of England, the Midlands and the North. The ‘father’ of this kind of art, comparable in importance to Hogarth in relation to caricature, was the then relatively little-known but remarkable painter Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–97). Wright of Derby precisely fulfilled Klingender’s criteria for the truly progressive artist, in being ‘not only a painter of philosophers, [but]… also a philosopher himself’,57 a man with a scientific temperament wholly at one with the manufacturing and intellectual luminaries of the Lunar Society, to whom Klingender attributed the initial creation of the Industrial Revolution. Wright produced a body of work, though only within a short period of about eight years before he went to Italy in 1773, fully expressive of the decisive union between science and industry that enabled the world-changing phenomenon of the new industrialisation: ‘Wright was as much a pioneer [in industrial subjects] as he was in glorifying science.’58 However, Klingender did not make the claim that ‘Joseph Wright was the first professional painter directly to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution’, a remark that has been frequently attributed to him. That sentence was written by Arthur Elton for the 1968 edition, and with the benefit of hindsight it is hard to image a fervent materialist like Klingender attributing a ‘spirit’ to the Industrial Revolution, or giving the artist such a passive role in relation to it.

Certainly, Wright of Derby produced paintings within a limited period between 1765 and 1772 in which people are shown expressing wonder at experimentation, or which focus on machines and processes of making. The great Experiment on a Bird in the Air-Pump, 1768 (London, National Gallery) and A Philosopher Giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in Which a Lamp is Put in Place of the Sun, 1766 (Derby Museum and Art Gallery),59 both exhibited at the Society of Artists in London, come in the former category, and the forges and blacksmiths’ shops, versions of which were exhibited in London in 1771–72, in the latter. But Wright’s paintings – brilliant though they are – do not quite bear the historical weight that Klingender puts on them. They are not really pictures about ‘science’, or at least about the kind of science that feeds directly into technology. In fact, as scholars like Benedict Nicolson subsequently realised, there is nothing new or even recent in the science or technologies represented in the paintings; the air pump and the orrery were not at all new by Wright’s time, nor were trip hammers or forges.60 Only a later landscape view, long after his return from Italy in 1775, of Arkwright’s Cotton Mills by Night, c.1782–83 (private collection)61 confronts industrialisation directly, and then in a highly picturesque moonlit context. The unmistakable sense of novelty in Wright’s ‘scientific and industrial’ paintings is probably less to do with the Industrial Revolution than with their use of light derived from earlier Dutch painting, of which Klingender shows great understanding and art-historical knowledge. It is also to do with the paintings’ formal ambiguity, the way that they hover between history paintings and portrait groups and genre scenes, as in the Air-Pump and The Orrery. This ambiguity gives even mundane scenes an unexpected portentousness, or, in the case of the two versions of the Blacksmith’s Shop (Derby Museum and Art Gallery, and Yale Center for British Art), set in the ruin of a great house and both dated 1771, a sense of humble events in great surroundings.62 But such issues of pictorial composition associate him more with the concerns of the London Society of Arts and the early Royal Academy, founded in 1768, where he often exhibited, than with his progressive provincial milieu.

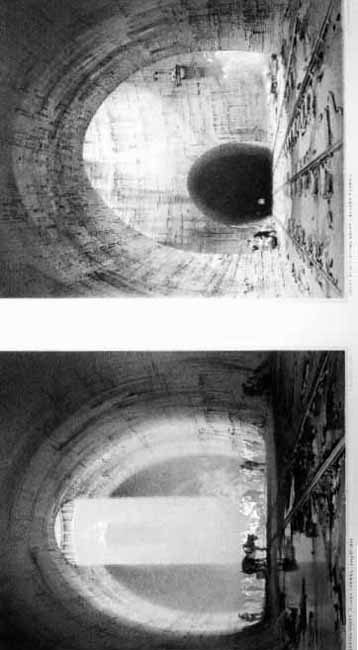

Klingender’s knowledge of the visual culture of industrialisation enabled him to recover from oblivion artists associated with each phase of the development of industry, from its heroic phase in the 1760s, when Wright of Derby was at his height, through the ‘Age of Despair’ of the early nineteenth century and the Railway Age, to its High Victorian triumph. Though there are impressive paintings and watercolours that respond to the sublimity of industry, Klingender finds the first 30 years of the nineteenth century easier to illustrate through the Romantic poets and early Victorian novelists, who are quoted extensively. One might expect, given the large number of paintings that relate to industrialisation in his oeuvre, that J.M.W. Turner would figure prominently, but, though a number of his works are mentioned, it is the sublime and myriad-figured paintings of John Martin that are more prominent in the book.63 This may simply be due to the fact that Klingender liked to parade recent discoveries rather than established ‘Old Masters’ like Turner, but he was undoubtedly captivated by the idea that Martin’s imaginary architecture could both be influenced by and influence ‘the style in which the engineers of his own time carried out many of their greatest works’. With hindsight, Martin’s paintings seem to be more at one with the speculative industrial culture itself than expressive of the dread that science had become a Frankenstein monster of doubt and despair unleashed on the world. Yet one of the greatest achievements of the volume is the rehabilitation of artists such as John Martin, several of whom, like J.C. Bourne are still less known than they deserve. Bourne’s lithographs of the building of the London and Birmingham Railway of 1839 are technical wonders in their use of lithography (Figure 11), but they also give a moving picture of the painful physical processes behind the work of the many thousands of labourers involved in railway building:

Contemporary calculations which claimed that the labour performed in building this railway greatly exceeded that spent on the Great Pyramid, become credible when one sees Bourne’s view of the great cutting at Tring, every foot of which was dug up and removed by hand.64

The railway age was for Klingender an age of further crisis for the new industrial society. It led to the replacement of the paternalistic capitalists of the eighteenth century, who were at least builders of communities, by the philistine bourgeoisie, a process completed essentially by the Crystal Palace, capitalism’s hour of greatest triumph. Klingender had nothing but contempt for the ostentation of these new bourgeois, whose vulgar taste was responsible for the ‘decline of English painting after Turner and Constable [which was]…not unrelated to the new standard of values established by the triumphant capitalists’. Art was now the victim of ‘Cashbox Aesthetics’,65 as Victorian painters were forced into painstaking representations of nature, or of banal sentiment. Klingender’s witty observation that ‘contemporary paintings of Highland cattle grouped meekly around a majestic bull irresistibly suggest the Victorian family’ was excised from the posthumous edition by Arthur Elton, who was distressed enough by Klingender’s blanket condemnation of Victorian taste to insert some paragraphs of his own into the text to excuse and argue against it.

Klingender made no mention of Karl Marx in the first six chapters of the book, but in the last chapter, entitled ‘Newfangled Men’, Marx is brought out exultantly with a long quotation from the famous speech celebrating the anniversary of the People’s Paper in April 1856. Marx notes that ‘in our days everything seems pregnant with its contrary’, in which ‘the newfangled sources of wealth, by some strange weird spell, are turned into sources of want.’ The solution is for ‘the newfangled forces of society…to be mastered by newfangled men – and such are the working men.’ They are the ‘firstborn sons of modern industry’, for they are ‘as much the invention of modern times as machinery itself’.66 This reaffirmation of the working man is also a reaffirmation of the dialectical process; the triumph of the ‘new’ Victorian bourgeoisie and the consequent misery it has engendered has created its opposite, an equally new kind of man who will finally bring about a socialist society as the culmination of the dialectic initiated in modern times by the bourgeoisie’s own challenge to feudalism.

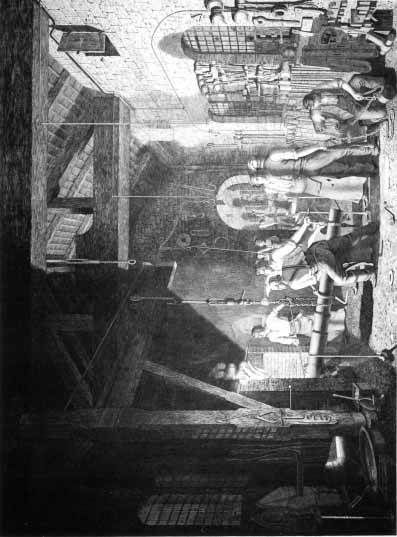

While Klingender can offer no single artistic figure of the stature of Wright of Derby to represent this new phase of emergent radicalism, he does make one ‘find’ among the provincial artists who sought to depict industrial life in the nineteenth century: James Sharples (1825–93).67 Sharples was a foundry worker from Bury, who after teaching himself to draw and paint had, on the strength of a very small body of work, a brief but brilliant period of national success. His life story was recounted in later editions of Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help,68 despite the unfortunate fact that he failed to make it as an artist and was forced to return in disappointment to the foundry. Sharples was unique in not using his artistic talent to distance himself mentally from the world of industry. His masterpiece, based on a painting he made in 1844–47 (Bury Art Gallery), is the magnificent steel engraving of The Forge (Figure 12), which took him ten years (1849–59) to complete. The Forge is a great technical achievement and a work of great artistic intensity. It also represented for Klingender the progressive belief among the early craft unions, of which Sharples was a member, that skilled workers in industry had the ability to master the new forces of production. Sharples’s Forge not only represents the new confidence of the ‘newfangled men’, but also art’s ability to express a sense of historical change that goes beyond the perceptions of the class from which it came.

Klingender at no point in Art and the Industrial Revolution mentions Lenin or other Soviet authorities and that is probably indicative of a post-war disillusionment with Soviet policy that was observed by others who knew him at the time. John Saville notes that he left the Communist Party after the Cominform break with Tito, but that it was ‘a slow drifting away rather than a sudden resignation’.69 Yet he remained firmly Marxist in his teaching, as is borne out by the historical trajectory of Art and the Industrial Revolution; but it is now Marxism firmly within a British, or even English, context rather than within the context of world revolution.

The reorientation of British art offered by Art and the Industrial Revolution, shifting its dynamic to the industrial areas of the Midlands and the North, is breathtaking in its sweep and boldness, and the passion with which it is written, but it is no criticism to say that it is based on a number of historical assumptions that have not all stood the test of time. One problem is the way that Klingender ring-fences the Industrial Revolution as a historical entity that can be treated separately from what was going on in the commercial world of London and its overseas markets. Whatever the inventiveness of the men of the Midlands and their own sense of a separate identity, their ‘industrial revolution’ did not happen in isolation from the financial wealth that had been generated in London earlier in the century from overseas trade. Nor were they culturally separate from London, despite their occasional contacts with France. Wright of Derby himself is as good an example as any. Though born in Derby, he learned his profession through apprenticeship to the London painter Thomas Hudson, who had previously been Joshua Reynolds’s master, and throughout his life he exhibited paintings for sale at the Society of Arts and its successor the Royal Academy. He did sell paintings occasionally to members of the Lunar Society, like Josiah Wedgwood, but more often to the local gentry, or to collectors outside the Midlands altogether.70

If the Industrial Revolution is seen not as a self-contained historical entity but as part of a continuum with London-based commerce, then there is, as many art historians have discovered, as much a case for seeing artists like Richard Wilson and Thomas Gainsborough as being engaged with historical change, in whatever form it might take, as those based in the industrial parts of the country. London artists can also open ways into that other ‘revolution’, the opening of Britain to the world beyond Europe in the development of a trading and military empire. The public sphere of London in the later eighteenth century, in which artists struggled for autonomy and control of institutions like the Royal Academy, was arguably just as important a site of class conflict as the factories and workshops of the North and Midlands. There is also a problem in Klingender’s lingering Romantic belief, shared with Lenin and the Lake Poets, that artists have as artists special powers to reach beyond their class and circumstances to engage with the deeper movements of history. We are more likely – now perhaps too much so – to see artists as actors on the same stage as other cultural producers, involved in complex networks that involve social mobility, entrepreneurial skills and forms of publicity, adapting as best they can the commodities they produce for the market place, which in the eighteenth century was overwhelmingly to be found in London.

Figure 12 James Sharples, The Forge, steel engraving, 1849–59. Private collection

It is also the case that, with certain obvious exceptions like Staffordshire pottery, most popular art, such as broadsheets and woodcut images, was made in London. There is, however, a deeper problem with Klingender’s idea of popular culture as a kind of stream running through the history of mankind from the earliest times to the present, an autonomous creation by ‘the people’ as opposed to those of power and wealth. The issue of popular art as representative either of national culture or of the labouring classes goes back even before Marx, and it has been the subject of rich debate in recent years. I have no space to summarise this debate, but I find especially persuasive Stuart Hall’s position in arguing against the idea of popular culture as an independent formation, on the grounds that, ‘there is no separate, autonomous, “authentic” layer of working-class culture to be found’.71 In Hall’s view, popular culture is always in a state of tension in relation to the dominant culture, represented in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by ‘the magistrate and evangelical police’. Hence no object can be fully and essentially popular in itself, but only in its relationship to the dominant culture.

We have perhaps also moved on beyond the almost exclusive concern with Britain forced on Klingender by the exigencies and restrictions of war and its aftermath, and which led him to underestimate the cosmopolitanism of artistic practice and experience in the eighteenth century. Wright of Derby used the money he made from his ‘industrial’ paintings to escape to Italy, with the intention of improving his professional and perhaps also his social skills. Hogarth, despite his loud protestations of Englishness and his contempt for foreigners, very wisely learned all that he could from French artists. For whatever reason, of Klingender’s two books on English art it is the Hogarth volume, though it is only a few pages long, that has proved so far to have been the more seminal. Studies of Hogarth, of caricature and of popular art have burgeoned over the last few years, in exhibitions, books and articles; the art of industrialisation as such has not prospered, though the taste and productions of the Victorian bourgeoisie have never been more fashionable. But then it is arguable that despite Klingender’s own personal loathing – characteristic of his time – for Victorian industrial artefacts, he set the terms for the renewed appreciation of the productions of an industrial society. This is because the teleology of his work demonstrates that art and material culture did not inhabit different worlds. While he wrote eloquently about the ‘great art’ of Hogarth and Goya, and recognised the achievements of artists throughout the ages, he also saw that popular prints and ‘low’ caricatures could match them in historical resonance. It is arguable, therefore, that his most enduring contribution to the history of art has been to help extend the study of visual culture into the demotic and useful arts, beyond the categories of art as it was, and is largely still understood.