7

Meyer Schapiro: Marxism, Science and Art

Despite the fact that Meyer Schapiro long outlived some of the main figures covered in this collection, unlike them he is known for no great scholarly opus. His doctoral dissertation apart, the two monographs he published in his lifetime were middlebrow picture books on Cézanne and Van Gogh,1 which, while exemplary within their genre, are not profound works of original scholarship, and suggest more his capacity as an inspirational lecturer than as one of the most exacting art historians of his time. With regard to his reputation in the latter category, Schapiro’s reputation rests primarily on a sequence of articles and essays that he published from 1931 onwards, many of which are now available in book form in the five volumes of his Selected Papers that have appeared since 1977, and which are probably the principal way in which his work is encountered today. Valuable as these volumes are, they present obstacles to an historical understanding of Schapiro’s work in that they are definitely a ‘selected’ presentation of his output, and they are organised thematically rather than chronologically. Many reviews, articles and papers of considerable interest are omitted, and Schapiro was evidently reluctant to include texts that contained views he no longer saw as representative.2

Among Schapiro’s numerous and lengthy letters to the novelist James Farrell from 1938–43, which were mainly written during the Schapiro family’s summer sojourns in Vermont, several allude to his difficulties in writing, and also to the pressures of his teaching commitments during the remainder of the year.3 However, these familiar academic complaints are not enough to explain the relatively small scale of Schapiro’s characteristic texts, or the laborious editing and polishing some of them went through before they appeared in the Selected Papers. More telling is his observation in a review of 1936 that ‘anyone who has investigated with real scruple a problem of art history knows how difficult it often is to establish even a simple fact beyond question and how difficult it is to make a rigorous explanation’.4 This sense of the challenge of precision in cultural analysis – which is also manifested in the dispassionate and measured terms of his prose – was reinforced by a distrust of large theoretical statements in a field that was not yet sufficiently developed to justify them. When in 1942 Farrell urged him to write a book on aesthetics, Schapiro described such a project as ‘an unrewarding job’ and something he would at best tackle in his old age; rather, he ventured, ‘I shall write on some problems of aesthetics, perhaps with the help of experiments and concrete analyses of single works of art’.5 At the root of these positions lay an epistemological stance and a view of the condition of the Marxist project that it is easiest for me to lay out through a mix of political biography and textual analysis.

Schapiro’s first publication was a retrospective review of Emanuel Loewy’s Die Naturwiedergabe in der älteren griechischen Kunst (1900),6 which appeared in the magazine The Arts, then the foremost modernist organ of the visual arts in the United States, where he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Waldemar George, Leo Stein, Diego Rivera and Stravinsky. Its author was only 21, and had graduated from Columbia University the year before with honours in philosophy and art history, and was starting the research into late antique and early medieval art that would eventually issue in his 1929 doctoral dissertation on the Romanesque sculptures of the French abbey of Moissac.7 While he was an undergraduate, Schapiro studied modern art in the galleries on Saturdays and familiarised himself with the writings of formalist critics such as Roger Fry and Willard Huntington Wright.8 Correspondingly, his essay starts out by boldly asserting that in rereading Loewy’s book ‘we become aware how much the modern arts have changed our view of the archaic and primitive’, so that the development from archaic to Hellenistic sculpture, which Loewy presented as a secular progress ‘today… seems to us a history of decay’. Loewy’s account was marred by ‘errors of artistic judgment and interpretation’ because ‘he overlooks entirely, in his zeal for a scrupulous record, that the change from arbitrary conceptions, from observed facts, generalized and treated abstractly, to literal representation and mere imitative forms, corresponds to a loss of artistic power’. According to Schapiro, the ‘anatomical discoveries’ of the archaic period seem ‘vigorous and fresh’ because of the way they are integrated with ‘design’, whereas the anatomical refinements of the Hellenistic look ‘academic and pompous’ because the artists’ research was ‘anti-artistic’.

‘Design’ and ‘realism’ (more accurately naturalism) are for Schapiro at this point antithetical qualities, and concern with the latter can only be at the expense of the former. With the growth of ‘realism’, ‘design must decay, because design is imaginative, arbitrary, emotional; it limits nature, it transforms appearances into eccentricities analogous to the human mind’. Thus whereas, except for some details, Loewy found the Hellenistic Farnese Bull (Figure 14) near ‘the highest perfection for a group in the round’, to Schapiro it had the effect of ‘a tableau vivant, utterly chaotic, with only the slightest pretense to artistic effect’. Conversely, while for Loewy the fact that the archaic Apollo of Tenea (Figure 15) suggested an artist who ‘started, not from the observation of nature, but from his own consciousness’, for Schapiro this was the source of its value, the back of this work being

a splendid and beautiful example of what a plastic coordination is, a unity which proceeds from an imaginative handling, which imposes arbitrary proportions, flattens particular planes, emphasizes specific lines, all for the sake of a sculptural ensemble, as unified and harmonious as a fine façade.9

Obviously ‘design’ stands here as something akin to Bell and Fry’s ‘significant form’, but for Schapiro it also entails a kind of apprehension of reality with cognitive potential. Moreover, Schapiro avoids the circularity and vulgar Kantianism of that concept by suggesting that the appeal of design may be grounded in psychological universals. Having observed that the ‘rhythm of music and poetry… are referable to the rhythmical character of life processes – respiration, pulse, peristalsis, growth, etc.,’ he continues:

so the appreciation of visual order may perhaps spring from the nature of mental imagery, from the mind’s manner of conceiving with ease, directness, power, clarity, and distinction, forms which were presented to its senses in confusion, overlapping, encroachment and complexity. It is not that the mental images are beautiful, just as the monotonous repetition of a heart beat is no aesthetic delight, but that their mutual relations, the order of their succession or dominance, correspond to what we call design, or express themselves as such… Good design is felt as a harmony analogous to the most efficient manner of perception, a means whereby the function is expanded and indulged in, and all values attached to fine seeing, heightened.10

I have given so much attention to this early text for three reasons. Firstly, because it illustrates so clearly a conception of value grounded in modernist aesthetics, which permeates all of Schapiro’s later writings, whether they concern the medieval or the modern. Indeed, it helps to explain why he took up such an unfashionable research topic as Romanesque sculpture in the first place. Although he would show himself later to be keenly aware of the historical contingency of modernist criteria and the dangers of applying them to the arts of other cultures in a way that turned them into mere ‘analogs of our own’, he would also assert that

the application to older art of the new concepts of structure and expression, which have been developed in modern practice, is a progress intellectually; for besides widening the scope of taste to include many hitherto impenetrable works, they have deepened our understanding of the formal mechanics and expressiveness of art in general and have brought us closer to the artist’s process.11

Secondly, it implies a conception of the aesthetic as rooted in common experience, thus fundamentally democratising it, which was probably owed in the first place to the teachings of John Dewey and Franz Boas, with whom he studied at Columbia.12 And, thirdly, because it shows an interest in the relations between the aesthetic and broader understandings of psychology and the body that demonstrates his commitment to a kind of materialist explanation. This comes out in his later work both in his quite frequent allusions to the connections between the ways in which the body is represented and emotional states, and in his occasional recourse to psychoanalytic concepts of repression and displacement.13

Socialism was part of Schapiro’s life from his childhood. His father, a secularised Jewish immigrant from Lithuania, read the socialist magazines the Jewish Daily Forward and New York Call in their Brooklyn home, and Schapiro himself joined the Young People’s Socialist League at twelve or thirteen.14 Years later he would recall being barracked by fellow Columbia students for advancing a socialist position during a freshman class on contemporary civilisation.15 However, by his own account, Schapiro was not much politically engaged in the 1920s, and he himself seems to have been one of those who was transformed by what he called the ‘the 1930–1933 discovery of Marxism’.16 The political framework for this ‘discovery’ was provided by the American Communist Party, a seemingly inauspicious setting inasmuch as in the early 1930s the party had just emerged from a decade of destructive factional infighting as a fully Stalinised apparatus that was positively discouraging to critical Marxist thought.17 But even if the intellectual mediocrity of the American party leaders was unmistakable, the full meaning of Stalin’s perversion of the Bolshevik ideal was not so readily apparent in the early 1930s, when the CPUSA could still attempt to make use of an original Marxist thinker of the stature of Schapiro’s friend Sidney Hook – at least until his differences with the doctrinaire orthodoxies of the Third International became too obtrusive to be overlooked. Three years older than Schapiro, Hook also grew up in Brooklyn, though, as he points out in his autobiography, in tough Williamsburg, rather than in the more middle-class neighbourhoods of Flatbush or Schapiro’s own Brownsville. Both attended the Brooklyn High School for Boys, where they were near contemporaries.18 Whereas Schapiro’s interests in the second half of the 1920s centred on early medieval art, Hook, who had taken his bachelor’s degree at the far more working-class City College of New York,19 was studying for a Ph.D. in philosophy at Columbia, writing a dissertation on the metaphysics of pragmatism. Like Schapiro, Hook had become involved with socialism as a teenager, but unlike him he was involved with the communist movement from 1919 or 1920, and when he entered Columbia in 1923 he was ‘an avowed young Marxist’.20 Moreover, in 1928 Hook travelled to Germany on a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship to spend a year studying post-Hegelian philosophy, where he became friends with the independent Marxist Karl Korsch, whom he later helped immigrate to the United States. The following year he visited the USSR to continue his researches at the Marx–Engels Institute in Moscow at the invitation of its director, David Riazanov – later a victim of the purges.21

Philip Rahv would tell James Farrell in 1939 that Schapiro knew more about Marxism than anyone he knew, ‘including Sidney Hook’. The choice of comparison is telling, but in the early 1930s it is likely that Hook’s original readings of Marx would have been an important example for him, even allowing for his own philosophical expertise and facility in German.22 In 1928, Hook had published a two-part article on ‘The Philosophy of Dialectical Materialism’ in the Journal of Philosophy, which was in part a critical review of Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, in the English translation of which he had played a role.23 This remarkably learned piece already laid out key premises of Hook’s position in the 1930s in its insistence that the distinguishing feature of Marxism was not so much its specific socio-historical interpretative claims as its method, and that understanding of Marx’s philosophical stance was crucial to the politics of Marxism as revolutionary praxis. ‘From the point of view of technical philosophy,’ Hook asserted, ‘historic justice has not yet been done to Marx and Engels’, and the key to their achievement was to be found in their early writings such as The Holy Family, the as yet only partially published German Ideology, and the ‘Theses on Feuerbach.’24 Hook was emphatic that Marxism was not a monism and did not rest on any form of materialist metaphysics. Historical materialism entailed the view that ‘human social activity is historically determined by economic development’, but this did not mean that Marx and Engels substituted for Hegel’s ‘idealistic fatalism’ a ‘materialistic fatalism operating through economic laws’. However, Engels himself, in his later years, had sometimes been a bit shaky on this latter point and had occasionally slipped into a reflection theory of knowledge and the ‘fatuity of the correspondence theory of truth’.25 The overall message of Hook’s article was that the Marxism of many of Marx’s ‘self-styled “orthodox disciples”’ misrepresented his philosophy, but also that the key to what was valuable in that philosophy lay in its ‘striking anticipation of the instrumentalist theory of knowledge’, so that a truly grounded recovery of Marx’s revolutionary principles depended on a historical materialism that took ‘its cues from the scientific pragmatism of Dewey’.26

In ‘The Philosophy of Dialectical Materialism’, Hook had sharply criticised Lenin’s position in his only philosophical work, but he had also intimated a contradiction in his assertion that the October Revolution of 1917 ‘was due in part to Lenin’s belief that Marxism must be interpreted as a voluntaristic humanism rather than as the teleological fatalism embraced by Social-Democrats everywhere else’.27 The implications of this were worked out in an article of 1931, in which, under the heading ‘der Kampf um Marx’, Hook pointed out that there was ‘a virtual war among socialists as to the real spirit and meaning of Marx’s thought’, a war in which there were four main contenders: self-styled orthodoxy, revisionism, syndicalism, and what he called the ‘reformation’ of Luxemburg and Lenin. Although the ‘Leninist–Marxists’ continued to ‘pledge lip allegiance’ to ‘theoretical constructions’ of Social Democracy that betrayed Marxism, their interpretation came ‘nearer than any other to the appreciation of Marxism as a philosophy of social revolution’.28 The title of this article was reused as the main title for Hook’s 1933 book Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx: A Revolutionary Interpretation, and it formed the basis of the book’s first part. In this, Hook gave a chapter to refuting Sorel’s syndicalist ‘heresy’ – which at least was not guilty of the reformist delusion; but his main target was the ‘Siamese twins’ of orthodoxy and revisionism: the mechanistic interpretation of Marx’s economic doctrines as ‘a closed deductive system’ that Kautsky had taken over from Engels, and the neo-Kantian conception of Marxism as an objective science that Bernstein had proffered as the philosophical basis for the reformism of the German Social Democratic Party, the logical outcome of which had been the party’s support of German imperialism and the mass slaughter of the European working class in the First World War.29 Orthodox Marxism was ‘an emasculation’ of Marx’s system, and the revisionist notion of the party turned it into ‘a benevolent organization with eschatological trimmings’.30 Once again, Hook argued that ‘whoever believes that sensations are literal copies of the world, and that of themselves they give knowledge, cannot escape fatalism and mechanism’, and thus the true philosophy of Leninism was not to be found in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, but in Lenin’s ‘practical writings’, and quintessentially, of course, in What is to be done?31 Lenin represented the ‘return to Marx’.

Hook’s Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx is an important work of Western Marxism, which should take its place in the canon alongside Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness and Korsch’s Marxism and Philosophy of a decade earlier, both of which he acknowledged in the book’s introduction.32 Despite their common criticisms of some moments in Engels’s late writings and their antipathy to neo-Kantianism, for Hook, Lukács’s version of the dialectic linked Marx far too closely with German idealist philosophy, and according to him Marx’s method was ‘naturalistic, historical and empirical throughout’. Indeed, at one point he says flatly: ‘Marx was an empiricist’ – although we should be clear Hook does not mean by this an adherent of philosophical empiricism and that he is rather stressing the differences between Hegel’s deductive dialectic and what he understood as the ‘genuinely experimental’ character of the Marxist version.33 None the less, Hook was emphatic that Marx’s ‘own best weapons were the weapons of dialectical criticism’, and that Marxism was a not an ‘objective science’ in the sense that the natural sciences might claim to be, but a ‘class science’ – as all social sciences were – in which subjective and objective were fused, because it was conceived to advance the conscious goals of a specific social group.34 As with Lukács, for Hook objective social knowledge and the perspective of the proletariat are not in tension, but actually necessary to each other. Yet for all his endorsement of Leninism, Hook’s writings – like Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness – set out a conception of Marxist science that the Third International could not tolerate, and like that work, Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx was condemned from within the communist movement – ironically as a ‘revisionist’ work. But whereas Lukács renounced his greatest achievement to continue working within the movement, Hook turned against it.35

In several ways, Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx can help us to understand Schapiro’s politics, since I take it as the most sophisticated exposition of the viewpoint that drew young intellectuals radicalised by the depression to the self-styled Leninism of the communist party, not realising – at least to begin with – that the doctrinal ideology of the Third International could not be refigured as an experimental revolutionary philosophy. Certainly Schapiro was in Hook’s circle in the early 1930s, and was active in the League of Professional Groups for Foster and Ford, a front organisation whose object was to mobilise support amongst the middle class for the communist candidates in the 1932 elections.36 Moreover, Schapiro’s correspondence with Hook from the early 1930s suggests their relations were not affected by Hook’s break with the party, and that Schapiro’s own view of it was highly critical – to the extent that he observed in mid 1933 that the organization would probably benefit from being made illegal.37 However, before saying more on Schapiro’s politics, I want to consider the ways in which Hook’s work may help us understand his development of a Marxist theory of culture.

According to Hook, ‘to be a Marxist means to be a revolutionist’, and correspondingly the choice facing contemporary capitalist society is between communism and barbarism.38 But although Hook believed that the Russian Revolution had brought a ‘release of creative energy…unparalleled in the history of mankind’, given the nature of the dialectic, this did not mean that communism involved a total rupture with the past. Communist culture was not ‘merely destructive to the inheritance of the past’, rather earlier achievements would be reinterpreted in ‘a new cultural synthesis’:

The permanent, invariant and universal aspects of human experience, as reflected in art and literature, reappear in a new context so that the significant insights of the past become enriched through the reinterpretation of the present.39

And in arguing against the monist interpretation of Marxism by Kautsky and Plekhanov, Hook gave a quite effective account of the theoretical parameters of the ‘relative autonomy of the esthetic experience’.40 Changes in cultural and intellectual life did ‘arise out of the social processes’, but they were mediated through forms and traditions of ‘autonomous domains with logical relationships uniquely their own’, and the nature of determination ‘in the last instance’ was ultimately related to the uses of cultural products. Reading Hook’s formulations on this point, anyone familiar with the rudiments of Marxism will recognise that they owe a lot to Engels’s late letters, from which he quoted liberally, publishing his own translations of four of them in an appendix.41 My point is not that Schapiro got his Marxist theory from Hook – in early 1932 both were involved in a project to publish a collection of essays on the ‘Marxist Study of American Culture’ for which Schapiro would have written on the fine arts, and the ideas may have come as much from his side. It is rather that there was a quite sophisticated and scholarly dialogue taking place grounded in a wide knowledge of Marxist writings.42

In explaining the nature of Marx’s dialectic, Hook argued that his work could only be understood properly once the ‘doctrines he is opposing’ were understood.43 The arguments about the relationship between Marx and Hegel that he set out briefly in Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx were developed at much greater length in his 1936 book, From Hegel to Marx, which was intended as the first of a three-part study of the sources of Marx’s thought. The larger points that need to be taken from this are that for Hook, Marx’s thought had become a historical object and that Marxist method entailed a continuous and unending process of critique. Opening a chapter in the earlier book, tellingly titled ‘Problems of Historical Materialism’, he observed: ‘A proper test of the claims of historical materialism could be made only by applying its propositions to the rich detail of politics, law, religion, philosophy, science and art. This would require not a chapter but an encyclopedia.’44

Schapiro too was filled with a Deweyan sense of the provisional and experimental status of the truths of both Marxism and the history of art. In a well-known review of a volume of writings by Vienna School art historians, he observed that in the United States the discipline was for the most part lacking in both empirical and theoretical rigour, adding, significantly, that it was ‘notorious’ how little it had been affected by ‘the progressive work of our psychologists, philosophers and ethnologists’.45 Yet while he recommended the work of Pächt, Sedlmayr and others as exemplary in its attention to the interplay between concept formation and empirical analysis, in almost every other regard he was sharply critical. The Vienna School might draw on Gestalt psychology and on logical positivism in some degree, but it was also premised on a characteristically Germanic distinction between what was understood as the ‘merely descriptive and classifying’ procedures of the natural sciences which governed the collection of ‘outward signs and evidences’, and a science of interpretation that was the only way to ‘penetrate and “understand” totalities like art, spirit, human life and culture’.46 Schapiro rejected this distinction as for the most part mystification and harmful to the sciences of nature and culture alike: ‘Actually, there is little difference, so far as scientific method is concerned between the best works of the so-called first and second sciences of art. They both depend on relevant hypotheses, precise observation, logical analysis, and various devices of verification.’47 Moreover, historians did not deal with absolute wholes, totalities in the Hegelian sense, but rather they addressed ‘isolated aspects of the work of art from defined points of view’. The Vienna School’s break with earlier methods was less profound than it appeared, since while they might show an advance in their approach to questions of form, like scholars concerned primarily with questions of attribution and historical precedents, they remained preoccupied with ‘individual objects’ and tended to ‘isolate forms from the historical conditions of their development, to propel them by mythical racial–psychological constants, or to give them an independent self-evolving career’. In brief, the School still purveyed a variant of Riegl’s concept of Kunstwollen, and it had no ‘adequate conception of history’ to direct its historical interpretations equivalent to the ‘scientific rigor’ its members demanded in their analyses of forms.48

We can get a sense from ‘The New Viennese School’ of what Schapiro thought he was opposing. But obviously it did not seem appropriate in the august pages of the College Art Association’s Art Bulletin to lay out the challenge of Marxist art history as a class science.49 Two months after the review appeared, he did this in a letter to a former student in which he observed: ‘of course there are more valiant and overt ways of fighting than through books and lectures on art, but the fight against bourgeois society takes place on every front – economic, political and cultural’. Doubtless with writers such as Sedlmayr in mind, he continued:

Bourgeois art study, as a profession, is usually servile, precious, pessimistic, and in its larger views of history, human nature and contemporary life, [generally] thoroughly reactionary. We do not overcome these things by abandoning the study of art, but by giving it a Marxist direction.

However, as Schapiro’s assessment of the Vienna School and his current writings illustrated, such a history would not ‘give up the techniques of research into details & fact developed during the last 100 years – on the contrary, it insists upon scientific method throughout’, while rejecting as unscientific ‘the typical methods & theories of interpretation of men like Riegl, Wölfflin & Dvořák’, who were the best of modern art historians to date.50

This division of tone and style runs through Schapiro’s published writings of the 1930s and 1940s, distinguishing his articles and reviews for left-wing magazines such as New Masses, Marxist Quarterly and Partisan Review from those for professional art history publications. Writing to Farrell in 1942, he observed of the article ‘Courbet and Popular Imagery’, which had appeared in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes the year before, that ‘the more important relations to political life and classes’ it identified would be missed by most of his colleagues, ‘or seem merely incidental and outside their own province’.51 Yet the Marxist framework is unmistakably present in the more academic art-historical writings, and partly in the leitmotiv of history as humanity’s self-emancipation that Schapiro took from the early Marx, and which Hook had done so much to publicise in the United States. Hook pointed out more than once that historical materialism was premised first of all on the critique of the religious residue in German idealism, citing the quotation from Aeschylus’s Prometheus in the preface to Marx’s doctoral dissertation: ‘In one word – I hate all the Gods.’ Schapiro embraced fully what Hook called Marx’s ‘animus against religion’,52 and in 1942 was so incensed by a conference at Columbia that questioned the value of science as a guide to ethics, that he proposed a counter-statement that would assert that ‘science remains the only reliable way of obtaining the knowledge with which to guide our actions in changing the existing order’, ‘the absolute values taken for granted in the conference have been exploded long ago’, and ‘the return to theology is itself a sign of intellectual and moral breakdown, not a recovery’.53 Correspondingly, in his writings of these years on medieval sculptural decorations, Schapiro emphasised both the way the church’s secular interests governed its theological programmes, and at the same time the ways in which what he perceived as the secular interests of the laity managed to find expression in marginal figures and themes.54 In 1938 he wrote to Farrell with regard to Chartres: ‘I do not think of the stories as superstitious when I see them in stone and glass, for they show in their artistic force the power of man to imagine and to shape things even when his scientific understanding is so limited; but it is this power which underlies also the capacity finally to overcome superstition.’55

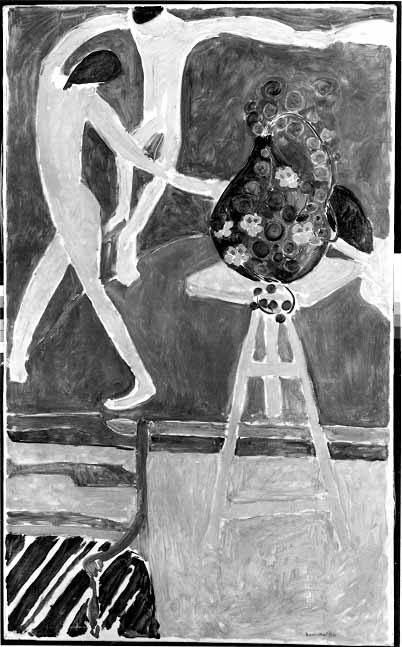

It might seem that Schapiro’s commitment to a modernist aesthetic would have come into conflict with the communist movement’s essentially instrumentalist view of art and the reductive model of realism that stood as its official aesthetic from 1934 onwards. But this was not a point of tension – to judge from the public record – until after his break with the movement. In 1932 he published a brilliant essay on ‘Matisse and Impressionism’ in a Columbia magazine, prompted by the artist’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art of the previous year. Matisse was exemplary of the ‘radical transformation of art in the last thirty years’, and also stood as the artist who was most effective in bringing it about. But, Schapiro went on, Matisse’s ‘Notes of a Painter’ was misleading in presenting his work as simply the antithesis of Impressionist ‘formlessness’, and in a carefully argued series of formal and iconographic analyses he showed how Matisse’s modernism was essentially dependent on the style he denigrated, which stood for both ‘really modern’ vision and, correspondingly, a view of nature that ‘dominates most of the art of the nineteenth century’. ‘Even the formal aspects of his abstract manner are inconceivable without Impressionism’, Schapiro wrote, so that in his Nasturtiums and Dance (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Figure 16), for instance, ‘a decorative composition is abstracted from the viewpoint of everyday vision’, comparable to that of ‘so frankly a realistic painter as Degas’; and thus ‘in the abstract design of Matisse it betrays the underlying Impressionistic view of objects, however altered by a pattern’. This is an essentially dialectical argument, which anticipates that Schapiro made against the view of each new modernist style as a purely formal reaction against a preceding one in his review of MoMA’s Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition of five years later.56 As on that later occasion, Schapiro insisted that form was inseparable from other aspects of a work’s meaning.57 Although Schapiro’s enthusiasm for both Impressionism and Matisse is evident, his caution that ‘the liberation of individualism’ that was ‘an intrinsic character of Impressionism…paralleled in other aspects of modern life’ was ‘not necessarily an advantage in the creation of good art’ should also be noted.58

For all its covert dependence on the Marxist conception of culture, ‘Matisse and Impressionism’ stands in apparent contrast to a review of the communist John Reed Club’s exhibition ‘The Social Viewpoint in Art’ from early in the following year. In this, Schapiro took the club roundly to task for its ‘confused effort to designate a united artistic front, to rally together all painters who represented factories, workers and farmers, in opposition to painters who represent bananas and prisms’, singling out the inclusion of both American Scene paintings by Thomas Hart Benton and a modernist view of Paris by Stuart Davis as symptomatic of the incoherence of its rationale. Schapiro’s point was a basic one, namely that the political import of works was not to be found in the objects depicted. Criticising both the club’s ‘mistaken devotion to mural painting as a “social” form of art’ and its inclusion of easel paintings destined primarily for private homes, he suggested that it should rather have aimed for a display of a ‘carefully prepared series of pictures, illustrating phases of the daily struggle, and re-enacting in a vivid forceful manner the most important revolutionary situations’, and examples of cooperative work by artists such as series of cheap prints, cartoons, posters, banners and signs. In the dispute that followed, one of the exhibition’s organisers accused Schapiro of coming close to Trotskyism in assuming that ‘proletarian art can exist only in a classless society’.59 Schapiro was not a Trotskyist as such, in 1933 or later, but he would certainly have accepted Trotsky’s view that social revolution was something that would last ‘not months, not years, but decades’, and that in the process of ‘fierce class struggles’ the proletariat would have neither the time nor the resources to make a culture of its own. Even in the USSR, Trotsky had written in 1924, ‘there is no revolutionary art as yet’, only ‘the elements of it’, and this art, when it came, would inevitably reflect ‘all the contradictions of a revolutionary social system’.60 The situation could only be more backward in the United States, where there was not the material base for such an art and where the outlook of the vast majority of the proletariat did not even reach the level of what Lenin called ‘trade-union consciousness’. This, it seems to me, is the fundamental premise underlying Schapiro’s judgements on the relationship between modern art and revolutionary art in the 1930s, and afterwards. It was not that one was intrinsically good and the other was intrinsically bad, it was rather that the economic and social base fostered a high level of attainment in one and not in the other – hence the title of his most elaborate published statement on the question, delivered at the American Artists’ Congress in February 1936, is ‘The Social Bases of Art’. In this, he argued:

The social origins of such forms of modern art do not in themselves permit one to judge this art as good or bad; they simply throw light upon some aspects of their character and enable us to see more clearly that the ideas of modern artists, far from describing eternal and necessary conditions of art, are simply the result of recent history.61

Two years later, he would reaffirm that ‘the conception of an art expressing the ideas and experience of the revolutionary movement remains a valid one’, pointing out that whilst most propaganda was ‘artistically of a low order, this is not a necessary condition’ – a view doubtless confirmed by the examples of Brecht and Rivera, both of whom he knew and admired. There was ‘no inherent antagonism of propaganda and art’, and ‘most works created simply to express the artist’s feelings’ or as ‘formal constructions’ were also deficient.62 But, like Trotsky, whom he now openly avowed as an idol, he expected the allegiance of artists to be voluntarily given and to emerge organically out of the process of social and political transformation.

This brings us to Schapiro’s break with the communist movement and its implications. As with the founders of the reformed Partisan Review – the literary organ of the New York John Reed Club, reconstituted as an anti-Stalinist publication in 1937 – Schapiro’s disenchantment with the Communist Party came partly because of the turnarounds of the Popular Front and the Party’s shift to a class collaborationist line.63 This led it to adopt an absurd style of American populism, which seemed an opportunistic and disingenuous betrayal of proletarian internationalism, and to replace the doctrine of revolutionary art with a compromised notion of ‘people’s culture’ that was anti-intellectual and more unfriendly to modernist experimentation than its predecessor. The Party’s full endorsement of the New Deal as politically progressive did not come until the latter part of 1937, but the change in its cultural line was evident earlier, partly because communist and fellow-travelling artists, writers and actors were drawn into the federal art projects, and particularly those of the Works Progress Administration, launched in August 1935. By late 1936, Schapiro was attacking the public art of the New Deal in the pages of the Artists’ Union magazine Art Front, and in the November presidential elections he voted for the socialist Norman Thomas, who ran on a straight ‘Socialism vs. Capitalism’ platform. (To put this in perspective, it is worth remembering that even such a milk and water socialist as Dewey was anti-New Deal). The clincher for Schapiro, as for so many others, was the Moscow Trials, and by early February 1937 he was an open supporter of the American Committee for the Defence of Leon Trotsky, which Dewey chaired, and Hook was instrumental in setting up.64 However, Schapiro’s trajectory is unlike that of most of the ‘New York Intellectuals’, in that he remained a revolutionary Marxist. This separates him sharply from Hook, whose anti-communist Committee for Cultural Freedom he refused to join, and in 1943 the pair had a rancorous exchange over the character of the war in the pages of Partisan Review – Schapiro’s position being intransigently anti-imperialist, so that he refused to endorse the United States and its allies.65 By 1940 Hook was describing Schapiro and Farrell as ‘political onanists’ because of their steadfast commitment to revolutionary politics, while two years later Farrell referred to Hook as the ‘embalming fluid of socialism’.66 For Schapiro, ‘professional anti-Stalinism’ led to a complete gullibility with regard to the war aims of the United States.67

However, for a true Marxist intellectual, the events of the late 1930s and the following decade could not but force some kind of taking stock. How had the Bolshevik experiment culminated in a state that contradicted the principles of socialism on almost every front, and that would enter into alliance with a fascist power and act in as imperialist a manner as the capitalist nations? Could Marxism as a revolutionary philosophy survive its perversion into the state ideology of a totalitarian regime? As Farrell observed in his diary in the dark days of 1940, ‘Marxists claim that their ideas correspond to reality. But that is a question. Do they?’68 For Hook, these developments caused a fundamental reassessment of epistemology and ethics,69 and a move from revolutionary politics to an obsessive anti-communism and apologias for American imperialism. Schapiro, by contrast, stayed an admirer of Lenin – for Hook, now a figure with absolute responsibility for Stalinism – and he continued to defend the Bolsheviks’ Jacobin morality on the same kind of Deweyan principles as Hook once had.70 However, he did come to reject the Leninist model of the party and developed a new interest in Luxemburg’s critique of it.71 This partly explains why although he and Farrell maintained relations with both wings of the American Trotskyist movement throughout the decade – having refused to take sides in its factional disputes – they did not identify as Trotskyists. Despite their enormous admiration for Trotsky as a revolutionary type, both felt there were deficiencies in his conception of dialectical materialism that were connected with the degradation of the Leninist model under Stalin, and that needed to be revised through an instrumentalist critique. Thus Schapiro wrote to Farrell in 1943 that he did not agree with Engels and Trotsky in their conception of dialectical materialism as ‘a formal science and as a set of laws’, although ‘they were correct in their idea that experience itself, the world of man and the world of non-human nature show characteristic features of process, movement, concreteness, crucial increment in change, interaction, and (in man) continuity and mutual determination of theory and practice’. Because of the transformation of historical materialism into a ‘formal dialectic’ in the interests of the Stalinist bureaucracy, he continued:

I think it is one of the more important tasks of our times to analyse Dewey’s philosophy from this point of view, to show to what extent the best in his thought agrees with Marxism, and then to reveal the contradictions and confusions that exist in his thinking because he has not carried out his program of thought consistently, compromising with traditional American political and social ideas, fearing to study social conflicts deeply, ignoring the vast contributions of the revolutionary movement of the nineteenth and twentieth century, and refusing to face the failure of his ideas about education, society, politics, war, culture (and even art).72

This continuing concern with the methods of the natural sciences and with pragmatist philosophy explains Schapiro’s friendships with distinguished logicians and philosophers of science such as A.J. Ayer, Ernest Nagel, Otto Neurath and Edgar Zilsel. It also accounts for his sharp criticism of Erwin Panfosky’s 1943 essay ‘The Study of Art as a Humanistic Discipline’, with its attempt to demarcate the humanities from the sciences and its association of Marxist critique in the arts with totalitarianism, despite his friendship with and respect for the scholarship of its author. The term ‘“humanistic”’ is not identical with ‘“human”’, Schapiro acidly remarked, ‘it has an archaistic flavour and smells from decrepitude every time it is dusted off and presented as a fresh ideal’. Being modern (in contrast to an assumption of classical values, which had lost their once progressive association) put us in a better position to understand the ‘universally human’ than any earlier civilisation, and ‘the label “humanistic” isolates the arts and philosophy from the sciences and social life and intimates pretentiously that the arts are a separate region in which the human being is truly formed’.73 In fact, ‘we recognize that the students of the humanistic discipline since the early period have been responsible for some of the blackest crimes of history’, and that ‘in the camps of nonfascists and fascists are products of both humanist and nonhumanist disciplines’.74 For Schapiro, modern science and modern art (and especially Cubism) were precisely kindred in their approach. Just as the philosophers and scientists of the early twentieth century had broken with their predecessors’ model of knowledge as ‘a simple, faithful picture of an immediately given reality’, and saw in scientific laws ‘a considerable part of arbitrary design or convention and even aesthetic choices’, leading to ‘a constantly revised picture of the world’, so had artists. Thus, ‘a radical empiricism, criticizing a deductive, contemplative approach, gave to the experimental a programmatic value in all fields’.75 Both contributed to the larger work of human freedom.

This position also illuminates Schapiro’s relations with the European émigré intellectuals, with whom he mixed in the late 1930s and 1940s, among whom were – in addition to Neurath and Zilsel – the Frankfurt School in exile, Max Raphael, Alfred Rosmer, Boris Souvarine and Edgar Wind. It is important to register that despite his passionately held political convictions, Schapiro could remain on friendly terms with those with whom he disagreed on key issues, such as Kracauer, Souvarine and Raphael – although the latter broke off their relations. Thus friendship does not mean coincidence in opinion. While he admired Adorno and Benjamin, and wrote a review for the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung in 1938,76 his characterisation of an editorial by Horkheimer as containing ‘a pessimistic, somewhat whining, criticism of the present state of society’, and ending ‘in a self-comforting faith in Roosevelt as a humanitarian under whose rule we are safe from fascist degeneration’, may serve to mark their differences.77 Quite simply, Schapiro retained a belief in the potential of the organised working class that was entirely absent from Frankfurt School analyses of the late 1930s. Although he shared Adorno’s aversion to claims made for the aesthetic status of jazz and to Hollywood cinema, his hostility to the American popular arts was significantly cast in far more political terms – namely that they were the cultural arm of US imperialism.78 This points to something fundamental about the reception that Hook and Schapiro had made of Lukács’s ideas, namely that they did not adopt the concept of reification, with all that implied about the opacity of social relations in late capitalist society.79 For Schapiro, Adorno’s ideas were ‘overdone, exaggerated’,80 which I suspect means that they were too close to a Hegelian deductive logic and insufficiently grounded in empirical inquiry. Which is partly to say that for Schapiro the dialectic was a kind of tool that one could apply if it was useful; it was not, as it was for Adorno, the necessary negative moment in all thought that aimed at the true.81

In the later 1930s and early 1940s, Schapiro was writing a book on realism in French art and literature from which his ‘Courbet and Popular Imagery’ article was extracted.82 But despite his huge admiration for Balzac, Stendhal, Courbet and Daumier, this was not because nineteenth-century realism could stand as a model for art of the present – after all, that essay concludes that the view of history in Courbet’s Enterrement à Ornans was ‘already retrospective and inert’83 and suggests that rather than being a revolutionary work, it measured the workers’ defeat in 1848. For Schapiro, realism in the visual arts was an essentially nineteenth-century bourgeois aesthetic, and his interest in it was as the forcing ground of the more radical culture of modernism. The great phases of European social insurgence had each issued in ‘an art of social protest, whether symbolical or realistic, doctrinal or humanitarian’, but 1848 had marked a divide, in that while before that year radical politics was essentially motivated by bourgeois interests in opposition to ‘feudal privilege or the alliance of the latter with a financial aristocracy’, afterwards, with the complete victory of the French bourgeoisie, the radical movement became the vehicle of working- and lower-middle-class discontents, and correspondingly anti-bourgeois. Given the social origins of artists and their ties to the bourgeoisie as the main patron class, they might be anti-bourgeois in some of their attitudes, but they were unable to identify with the project of proletarian revolution.84 Having helped to create a ‘critical conception of culture’, the bourgeoisie found itself confronted by a class that demanded a genuine equality, not just a formal political and social equality. As a result, it began to look more favourably on ‘the older institutions that had once been criticized – especially religious authority and fixed moralities’, and ‘to recast the old formulations of its values’, only bringing them out for ‘holiday occasions’. Correspondingly, there came a shift in culture, whereby art, ‘from being an instrument for the critical exploration of one’s world…gradually shifted its ground to the individual more private and passive elements within culture, to the sphere of intimacy and pleasure’.85 In so far as a great monumental art illustrating social revolution had emerged in the twentieth century in Mexico, it was because the Mexican revolution was an essentially bourgeois revolt that garnered ‘the support of almost the entire cultured strata of the country in the struggle against the great landholders and foreign imperialists’. By this measure, Socialist Realism, as the art of a repressive state bureaucracy was necessarily retardataire, and indeed showed ‘a mediocrity and artistic conservatism unequalled in any capitalist country’. Contemporary Soviet art, Schapiro wrote in 1938, was essentially academic and dull: ‘it corresponds to a labor and bureaucratic aristocracy that is plebeian and enjoys a petty bourgeois leisure’. It was ‘neither revolutionary nor socialist nor realist’. The subordination of art to the interests of the state was not a ‘necessary Marxist view’, and indeed ran counter to ‘the whole tradition of socialist freedom and the democratic values of the proletarian revolution’.86

As Schapiro told a university audience in 1948, reiterating an argument he had made twelve years before at the American Artists’ Congress, the ‘individualism of modern art, far from being a denial of social relationships’, was the ‘fruit of a certain mode of social relationship’, a mode ‘that was itself the consequence of centuries of struggle to overcome the repressions of or limitations on freedom and individuality vested within old established institutions and laws’.87 Modern art was inherently democratic and internationalist in its values, and it stood for an ‘attitude of constant self-transformation and growth’ in the individual. It might seem that we are encountering a kind of characteristic Cold War stance here, except that Schapiro thought his own society was almost as unfriendly to modernism as the totalitarian states were – ‘relatively few of the wealthy in this rich nation support art’ – and he stressed that the idea of individual freedom embodied by modern art was ‘a source of deep conflicts and difficulties within modern life because of the disparity between assumed values (the legally or juridically described values, the constitutionally defined values) and the actuality of life for the great majority of people.’ Contemporary American society, Schapiro observed, was not ‘a truly democratic society’, and the hostility modern art prompted was the result of this.88

Schapiro saw the movement of modern art in the period prior to the First World War as having an ‘ethical content’, because the ‘progressive emancipation of the individual from authority, and the increasing depth of self-knowledge and creativeness through art’ matched with a larger struggle for the individual’s right to self-realisation, and ‘a trend towards greater freedom’, across a range of different fields.89 In that period, cultural life had ‘a kind of militancy’ that gave it ‘the quality of a revolutionary movement’, but in the reactionary cultural climate of the early 1950s – ‘our painful discouraging age’ – modernism seemed to show ‘a slackening or stagnation’ and was lacking in the ‘idealistic individualism’ of the earlier moment, which was premised on greater confidence in being able to re-order social institutions to ‘humane ends’:

While the new art seems a fulfilment of an American dream of liberty, it is also in some ways a negation. In suggesting to the individual that he take account of himself above all, it also isolates him from activity in the world and confirms the growing separation of culture from work and ideal social aims.90

This essentially pessimistic view of contemporary culture is filled out in the important 1957 essay ‘Recent Abstract Painting’, although here the tone has become rather more disconsolate. Paintings and sculptures, Schapiro pointed out, were ‘the last hand-made personal objects’ within a social order dominated by the division of labour. In a world in which the life of most individuals was subordinate to unsatisfying practical activity, ‘the object of art is, therefore, more passionately than ever before, the occasion of spontaneity or intense feeling’. Abstract art met this need best, because it refused ‘communication’ in a world in which communication had been utterly instrumentalised and reduced to a notion of the most efficient stimulus to produce a given response. More than any other art, it corresponded to ‘the pathos of the reduction or fragility of the self within a culture that has become increasingly organized through industry, economy and the state’. Although it had no specific political message, abstract painting was ‘the domain of culture in which the contradiction between the professed ideals and the actuality [of our culture] is most obvious and often becomes tragic’.91

Leaving to one side the persuasiveness of these formulations, one might have expected that the author of this text – so redolent of the Marx of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts and of certain Frankfurt School pronouncements – would have felt some sympathy with the New Left. But although he opposed the Vietnam War, like so many former radicals of his generation, he kept aloof from the new radicalism, taking no public stance on the student occupation of Columbia of 1968 or on the violent police repression that brought that episode to an end.92 This did not prevent his work from having a greater effect on New Left art history in the United States and Britain than that of any other earlier Marxist art historian, his interpretations acting as a spur to important studies of medieval sculpture, Courbet, Impressionism, and Abstract Expressionism. But this influence was more a response to individual hypotheses than it was to the underlying system of his work, which can only be teased out from the unwieldy corpus of texts he has left us piece by piece. It is as a preliminary to a Marxist reading of that system that this essay is offered.