CHAPTER 5

Why Spiders Came to Dominate Schooling

If it ain't broke, don't fix it! Chapter 3 argued that “more of the same” is not on track to reach meaningful learning goals. Chapter 4 argued that the existing large, top-down, input-oriented ecosystems of schooling (metaphorical “spider” systems) present solutions as problems and hence bring as many problems as solutions. But this leaves the question of why countries have the school systems they have. Before entertaining notions of sweeping systemic reform, we ought to have a good account of why things are the way they are. In Voltaire's Candide, Dr. Pangloss's narrative—that things are the way they are because this is the best of all possible worlds—might just be right, even if the best of all possible worlds is pretty mediocre. It's a pretty good rule of thumb not to mess with things you don't understand. Before moving on to a chapter laying out new approaches, I owe you an answer to the hard question: if spider systems are so terrible at providing learning, why do so many countries still have spider systems?

Three big questions about schooling are:

—Why has the expansion of public schooling been so universally successful?

—Why does government directly produce (and not just provide through financing) so much of basic schooling?

—Why does the government produce schooling in spider systems: top-down, hierarchical organizations of massive scale?

Perhaps the answers to those questions are really simple:

—Because schooling is so good and is universally recognized as such.

—Because governments are the best at producing schooling.

—Because big is the best size for schooling systems.

If this is the right account, then fixing schooling to meet the learning gaps will not require fundamental change, just trying harder. Perhaps more of the same, but done better, and with more money, really is the solution to all ills.

However, this simple Panglossian account of the rise of government-owned and government-operated spider systems as the dominant system of basic education has very little going for it. An alternative account capable of explaining the historical rise of government-operated schooling, its successes in mass expansion, its present features, and how it functions as a spider system, as well its failures, has three essential elements:

—The inculcation of beliefs—or socialization—is not third-party contractible.

—Nation-states care about, and act to control, the socialization process, through the direct production of schooling.

—Isomorphic mimicry is a powerful force in shaping the diffusion of institutional organizations across nation-states.

With these three analytical pieces in place, I can explain everything we observe about education systems in the world today. I can also dismiss for what it is the Panglossian nonsense that gets said about these questions. Once we have cleared the debris of the false necessity for the way things are, we can move on to discussing in the next chapter the essential characteristics of an alternative to spider systems: open-structured, performance-pressured, financially supported, locally autonomous starfish systems of schooling.

The Inculcation of Beliefs Is Not Third-Party Contractible

I don't care too much for money,

Money can't buy me love.

THE BEATLES

The Beatles knew, as everyone does, that money can't buy you love. Why not? If I tried to buy love, I could never be sure the person was not faking it. Someone could act like she loved me but just be pretending. Love is not observable. Moreover, a market in love would require that love not only be observable between two people but also be verifiable. Could a third party reliably settle a contractual dispute between two parties over whether money had bought love? Could a paying lovee who felt defrauded by a contracted lover successfully get her money back? Love, being neither observable nor verifiable, is not contractible.1

In Vienna, Virginia, a perfectly ordinary suburb of Washington, D.C., Robert Hanssen lived the apparently perfectly ordinary life of a career bureaucrat for the FBI. Perhaps his most remarkable characteristic, those who knew him said, was that he was a fervent conservative Catholic, attending mass daily at 6:30 a.m. (and often again during the day) and sending his daughters to an Opus Dei–operated private school, where his wife taught religion. The reality was apparent to no one: Robert Hanssen was a spy for the Soviet Union, then for Russia, and remained so, off and on, during nearly all his FBI career from 1979 to 2001, when he was caught. This outwardly fervent anticommunist was perhaps the most damaging U.S. double agent in the history of the Cold War, playing a role in the loss of nearly every active U.S. asset in the Soviet Union in the period 1985–1986. Love is not the only thing that can be faked. So can loyalty.

If money cannot buy you love or loyalty, can it buy the teaching of love or loyalty—or of any belief or mental disposition, for that matter? I have a friend who is an excellent musician. He is also, as am I, a Mormon, a historically quirky American denomination with doctrinal beliefs far from the Christian mainstream. My friend worked his way through a PhD in choral conducting as the director of music for a local Catholic congregation. He had responsibility for the Sunday service music (playing the organ) and for directing the congregation choir, including its Christmas and Easter concerts and teaching the youth choir to sing. It is unremarkable that a Catholic congregation would hire a Mormon music director. But if the same congregation were to contract out to a Mormon the teaching of the youth Sunday School classes, it would be remarkable? Why can money buy teaching religious music but not the teaching of religion?

Suppose a student learns to speak Swahili and after a period of instruction can carry on a conversation with a native speaker and can read texts in that language. If the student reports to a friend, “They think I have learned Swahili, but I really haven't, because I don't believe in Swahili,” most people would regard this as an exceptionally odd statement. Perhaps he might not enjoy Swahili or have the disposition to speak Swahili, but a person's functional mastery of Swahili can be separated from any mental states he might have about it.

Now suppose the same student is being taught to pray. For instance, suppose he has learned the series of words Christians call the Lord's Prayer, has learned to say those words with appropriate inflection and affect, and has learned the appropriate circumstances in which to repeat those words. In fact, imagine the student could pass any conceivable external assessment of his ability to pray. If the student reports to his friend, “They think I have learned to pray, but I really haven't, because I don't believe in praying,” in this case he is right—he has not learned to pray.

I define a skill to be something for which the demonstrable performance is everything, while for a belief, a person's mental state is independently important. The distinction is not between those things that are physical and those that are mental, as skills run the gamut from weight-lifting or tennis to algebra or chess. The key analytical difference for which contracts and transactions are possible is that no one can pretend to have a skill he or she does not have (though of course, people can pretend not to have skills they do have), whereas people can, and do, pretend to hold beliefs they do not hold.

Skills are observable and verifiable. Hence skills are contractible and instruction in skills is directly contractible. Most important, instruction in skills is third-party contractible.

The distinctions between contractible, directly contractible instruction, and third-party contractible instruction can be elucidated using foreign language skills as an example. Suppose an American organization wants employees who can speak French. There are well-developed rankings of language proficiency and established expertise in language skill assessment. In an hour or less, any organization can reliably assess a person's maximum language proficiency (again, a person can fake not speaking French, but not vice versa). Speaking French is observable. Objective assessment is also verifiable such that, if an employee felt the organization were attempting to cheat on a promised incentive for speaking French, a third party could adjudicate whether or not “This person speaks/understands/reads French at the specified level of proficiency,” and hence could enforce that contract. This means organizations can contract for speaking French by, say, hiring only people who speak French at a given level of proficiency or by paying a wage premium that is based on the level of language skill, with higher bonuses or any of a variety of incentives.

Language instruction is also directly contractible. That I don't speak French is observable (either painfully or laughably so for my French-speaking friends, depending on their sensitivity), but were I to want to learn to speak French, I would have an array of contracting options. I could hire a tutor, I could buy a commercial “teach yourself” service advertised in airline magazines, I could enroll in a course from any of a variety of institutions, I could try to teach myself with an online course. Since I can have my language proficiency objectively assessed at relatively low cost, I can easily assess my progress and switch among providers of instruction depending on my progress.

The most interesting case is if an organization wants to encourage its existing employees to acquire French skills by subsidizing instruction in French. This creates a “make versus buy” decision for the organization. The organization could “make” French instruction by hiring an employee to offer French instruction to the organization's employees free. Alternatively, the organization could engage in third-party contracting with its employees by agreeing to subsidize some portion of the cost of French instruction. This could be as simple as allowing employees to use work time to receive tutoring (from their choice of tutor) on-site. Or the organization could agree to pay a flat rate of X dollars of the employee's instruction from any authorized course of French instruction (allowing employees to “top up” by choosing more expensive courses if they choose). There is a wide array of organizational strategies, from just paying for skills and not subsidizing skill acquisition at all to a variety of ways of encouraging instruction. The optimal organizational choice will be a complex function of how costly it is to observe the skill, how fungible the skills are outside the organization, the determinants of skill acquisition in relation to the individual's own ability and effort, and the risk aversion of employees (what if employees pay out of pocket for instruction but fail to reach the wage bonus threshold?).

Table 5-1. Why money can't buy love and why governments do not give vouchers for schooling, all in one table.

| Skills/Factual knowledge (Foreign language, algebra, music, tennis, chess, test prep) |

Beliefs/Attitudes/Dispositions (Love, loyalty, faith, duty, honor, patriotism) |

|

| Contractible (observable and verifiable)? | Yes (Hiring or incentive mechanisms exist, based on pay for demonstrated skills.) |

No (All implicit, based on inferences from behavior; arm's-length transactions are seen as suspect.) |

| Instruction directly contractible? | Yes (Thriving markets exist for instruction in skills through multiple modalities—tutors, classes, assisted own instruction.) |

Yes (Individuals can choose their own instruction in beliefs because as they are direct participants, the instruction is observable.) |

| Instruction third-party contractible? | Yes (Organizations have an array of “make” versus “buy” choices.) |

No (Organizations must “make,” not “buy,” to avoid “insincere teaching.”) |

Whether or not third-party contracting for instruction in French skills is the organizationally optimal choice, it is a choice, because the skill and instruction in the skill are contractible and incentives can, in principle, be constructed such that the individual's, the instructor's, and the organization's incentives are aligned. Moreover, in my analysis of the organization's incentive structure for French skills, the organization's fundamental goals did not really matter: one can imagine the Catholic Church, the U.S. Marines, Wal-Mart, and Amnesty International all sending their employees to the same class in conversational French (table 5-1).

Organizations typically want long-term employees to be personally committed to the vision, mission, and mandate of the organization. The Catholic Church wants priests and nuns who believe in God, the U.S. Marines wants soldiers who believe in the Corps, Harvard University wants faculty who believe in the value of research (if not in Harvard itself), Amnesty International wants workers who believe in human rights. These beliefs come with a variety of descriptions: faith, duty, loyalty, commitment; but all of these traits have in common that they are neither directly observable nor verifiable in that they cannot be reliably assessed at a feasible cost or time in an intersubjectively reliable way.

The example of double agents in the world of espionage is exotic but nevertheless instructive. Robert Hanssen rose to be one of the top FBI officials for ferreting out double agents in the U.S. intelligence community on the basis of his apparently sincere anticommunism and loyalty, while in fact he was the double agent. The counterpart in the world of skills is simply impossible to conceive of. Imagine discovering that the top cellist for the New York Philharmonic cannot really play the cello. An all-time great tennis champion like Andre Agassi can write a memoir telling us he hated the game of tennis, but he could not possibly reveal he could not play superb tennis (although, lamentably, that could be in my memoir). Double agents illustrate there is no cheap and reliable way to observe or verify loyalty. Therefore, simple incentive schemes for contracting or for third-party contracting of instruction, such as paying a wage premium for those who speak French or paying for French instruction, are not possible. The elicitation and demonstration of commitment to the core values of organizations require much longer periods of observation—and typically lower-powered incentives.

Beliefs are not contractible because only I know (if only imperfectly) what I believe. Speaking for myself, I know that I mislead others about my true beliefs all the time (“Have you lost weight, sir?” “Your child's cello playing was wonderful.” “My, what a lovely baby.” “Loved your recent paper”), but I know what I really think. However, for that same reason, instruction in beliefs actually is directly contractible: as the intended recipient I both completely observe all of the instruction and can make some, if only imprecise, estimates of its impact on my beliefs.

Third-party contracting for the inculcation of beliefs, however, runs the danger of a collusive contract between instructor and student to produce insincere teaching—and hence thwart the interests of the third party who is paying for the instruction. Suppose, as is true in many politicized environments, that my career depended on being a loyal Baathist, or loyal Communist, loyal environmentalist, or, in a religious regime, a devoted follower of this or that denomination, or, in a secular regime, not having a religion at all. Then I would have the incentive to engage an instructor with the following contract for insincere teaching: “Teach me how to appear to be a loyal follower of ideology X, while reminding me periodically that ideology X is a crock.”

More mundanely, consider an organization's “make versus buy” decision for instructional activities intended to build commitment to the organization's vision and mission. Could the organization just “buy” such instruction by giving employees a subsidy for “loyalty-augmenting” instruction that the employees themselves contract from third parties? Third-party instructors may maximize their attendance by offering the following deal: “I will really maximize how much fun you have during my course, and allow you to retain whatever bitter and cynical attitude you have about your organization, but I will also teach you how to plausibly pass an assessment of loyalty.” For the organization to prevent this insincere instruction in beliefs when the organization's incentives and the employees’ incentives differ in the desired outcome of instruction, the organization must exert more direct control of the process of instruction. In the limit, they want instructors who are themselves sincerely loyal to the firm or, at the very least, whose incentives are completely controlled by the firm, rather than instructors whose incentives are to please the market of employees who self-select.

Even outside formal schooling there are instances in which the make versus buy choice for instruction is based on the difference between skills and beliefs. The U.S. Army, for instance, contracts out the instruction of officers in some skills (language training, economics) but controls directly all the dimensions of training intended to induce service loyalty and unit cohesion. Many churches contract out child care in church-owned facilities or musical skills such as organ playing to people of different faiths, but few mainstream churches contract out Sabbath Day sermons or religious instruction to outsiders.

Priests and Marines and Wal-Mart employees might end up in the same courses (real or virtual) for skills like speaking French or how to use a spreadsheet. But churches will contract out music but not sermons. The U.S. Marines contract out skill acquisition but not their basic training—even branches of the U.S. armed forces don't share basic training. Wal-Mart employees have motivational programs run by Wal-Mart.

Instruction in beliefs is not third-party contractible, so organizations will choose to make, not buy, the inculcation of beliefs.

The Rise of Schooling: Origins of the Modern

An “official” educational enterprise presumably cultivates beliefs, skills, and feelings in order to transmit and explicate its sponsoring culture's ways of interpreting the natural and social worlds.

JEROME BRUNER, THE CULTURE OF EDUCATION

When I was a teenager my father used to tell me, “Whenever anyone tells you anything, your first question should be, ‘How would they be better off if you believed them?’ ” My first reaction was that my father was a cynical old coot. My second reaction was to think he only wanted me to think that so that I would listen to him more and to others less—which showed I understood his fundamental lesson, perhaps even too well. But it turns out my father only appeared to be a cynical old coot because he was not a French intellectual. Michel Foucault, quite possibly the most influential intellectual of our times,2 was saying nearly the same thing, but in less penetrable philosophical terms (and in French): that behind discourse we should look for power, that “reality” is not “discovered” but rather is socially constructed, often to serve the ends of powerful forces. The fun part of deconstruction is recovering the reality that existed before the dominant social construct became the “common sense” that now constrains discourse.

In the aftermath of the Meiji Restoration there were quite widespread popular protests with the slogans, “Down with conscription! Down with the solar calendar! Down with public schools!” In our current reality it is hard to entertain the idea that “Down with public schools!” was the slogan of a popular protest movement that the authorities suppressed with military force.

Public schooling, like any truly successful institution, projects its own inevitability into the fabric of language itself. The Millennium Declaration was signed by 147 heads of state as a consensus about the goals of development, and part of this consensus became elaborated into the Millennium Development Goals, which are to “achieve universal primary education,” for which the target is “all children can complete a full course of primary schooling.” But nothing could be more obvious than that education, defined as the preparation of children and youth to take on their social, political, and economic roles as adults, has always been universal in every society. Following the advice of my father and Foucault, you should ask yourself, why did 147 heads of state, ranging from democratically elected visionary leaders to generals to autocrats to kleptocratic thugs, all agree to conflate the obviously different concepts of “schooling” and “education”?

Returning again to the chapter's three big questions: Why has the public school as an institution been so successful? Why are so many schools run directly by governments? Why are the government organizations that run schools so large? Or, wrapped together into one question: how did governmental spiders become the dominant and successful system for schooling?

The answer for the “first movers” (those countries that built and expanded systems of universal basic schooling in the era from 1870 to the 1920s) is easy and was recognized as such during the time. Only our historical distance from schooling's origin has allowed mythic narratives to replace the contemporaneously obvious facts. The answer is that the rise of the modern economy, with the shift from traditional agriculture and craft production to larger organizational units of production carrying out new activities, implied that more and more parents felt their children needed more exposure to formal schooling as part of their education. At the same time, the consolidation of the modern nation-state as a mode of political organization required an extended process of socialization to mold the new citizens.

That is, if there were to be an extended period of schooling in which skills and beliefs were produced together, then the elites and leaders of the consolidating nation-states understood that the state must control that socialization, and understood too that this control required not just that the state support schooling but that, since the inculcation of belief was not third-party contractible, the state had to directly produce schooling. The political leaders understood that the fundamental contract had to be not directly between parents and teachers but between the state and teachers.

The resulting modern systems of schooling depended on how the various ideological struggles over the control of socialization between nation-states and parents played out. Since the most important competitors for the socialization role of education before the state were religions, the contest between and among state, society, and religion determined the ultimate size of the governmental units that controlled education. A series of vignettes from various countries illustrates how these forces played out. Notice that in none of these narratives do any Panglossian elements (elites providing schooling as a response to popular pressure, a benign state, the superior technical efficacy of the mode of the organization of schooling to produce greater learning of skills) play any role in the determination of the system of schooling.

Japan in the Early Meiji Period

In administration of all schools, it must be kept in mind, what is to be done is not for the sake of the pupils, but for the sake of the country.

MORI ANORI, JAPANESE MINISTER OF EDUCATION, 1886–89

Before the Meiji Restoration in 1868 there was a mix of schools and schooling that, with almost no direct influence or support of the national government, had already achieved quite high enrollment rates, estimated at 79 percent for boys and 21 percent for girls in 1854–1867. In 1873 the new government launched a new centralized school system (modeled on the French system) in which the national ministry dictated curricula and texts. This was not primarily an expansion of schooling but a bid to control the existing schooling. While compulsory, this schooling was not free: there were individual tuitions to be paid, and nearly all of the costs of basic schooling were locally borne. This new system was not popular, and riots broke out sporadically around the country between 1873 and 1877 that had to be put down with force. Whatever the motivation of the disturbances, the slogans often focused on three resented features of the new regime: conscription, public schooling, and the solar calendar. Over the decades of the 1870s and 1880s, as the public schools grew, three-way ideological debates raged among those emphasizing utilitarian skills (and Western ideas), traditionalists emphasizing Confucian training, and nationalists emphasizing loyalty to the nation-state (as embodied in the emperor). By the 1890s the nationalists were transcendent, promoting a dual educational system that had a “compulsory sector heavily indoctrinated in the spirit of morality and nationalism.”3

Turkey and Atatürk's Republic

The Turkish education system aims to take the Turkish people to the level of modern civilization by preparing individuals with high qualifications for the information age, who…are committed to Atatürk's nationalism and Atatürk's principles and revolution.

TURKISH MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, 2007

In March 1924, barely six months into his presidency, Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) launched the opening of the Grand National Assembly with a speech that announced three bold strokes: “safeguarding” the new Republic, abolishing the caliphate, and introducing the reform of education. The Law of Unification of Instruction placed all educational institutions—religious, private, and foreign—under the control of the Ministry of Education. This was indeed a bold stroke in a country whose population was overwhelmingly Islamic (and considered itself a, if not the, center of the Islamic world) and where the greatest part of education had been undertaken in schools controlled by religious authorities. Once education came under the control of the Ministry of Education, religious lessons were first made voluntary, then abolished at the secondary level, and then abolished altogether in primary schools by 1932. Just how unpopular this move, undertaken by a small “modernizing” secular and nationalizing group, was is difficult to gauge, as from March 1925 to March 1929 the government operated under the Law for the Maintenance of Order that provided for “extra ordinary and, in effect, dictatorial powers” (Lewis 1961, 266). As democracy has returned to Turkey, Islam has returned to Turkish schools. Since 1950 students in grades four and five have received religious instruction (with a chance to opt out), and religious instruction was reintroduced into secondary schools in 1956–1957. Nevertheless, as late as 2007 the Ministry of National Education openly proclaimed its fundamental goals for skills and socialization as a commitment to Atatürk's nationalism and the revolution.

France and the Laicism of the Third Republic

Let it be understood that the first duty of a democratic government is to exercise control over public education.

JULES FERRY, FRENCH MINISTER OF EDUCATION (1879–83)

France is the clearest example of the struggle between the religious—in this instance, Catholics—and the secularists over the control of schooling, which necessitated increasingly central control to resist the localities in which religious instruction in the schools was popular. The Ferry laws mandated free instruction in 1881, but, as many communes met their obligation to provide schooling by allowing the local Catholic parish school to be the “public” school, the law of 1883 mandated that all public education be secular. Not only that, but the threat of “insincere teaching” led to a ban on any cleric teaching in any public school.

The centralizing tendencies that result from a geographically widespread conflict between a secularist nation-state foundational ideology and a relatively homogeneous religious or cultural alternative is, of course, not the only possible outcome. Sometimes religion wins.

The Netherlands and Belgium

The former Low Countries, Netherlands and Belgium, today have respectively 68 percent and 54 percent of primary school enrollment in the private sector. The Dutch levels of private schooling are twice as high as in the next highest European country, Spain. The basic system has money follow the student. While the government produces schooling, parents choose their school freely from among available suppliers, and the state provides payments directly to schools on a funding formula that treats publicly operated and privately operated schools—including religious denominational schools—on an equal basis.

The lack of a public monopoly is not for lack of effort: the state did in fact try to secularize schooling, beginning in 1806, when Holland was “liberated” by the French. However, Holland had a long history of religious toleration and was deeply, and nearly evenly, divided along religious lines between Catholics and various denominations of Protestants. No religious denomination would trust a public school system to be either fair to religion (given the secular values of those allied with the French) or neutral between denominations. The compromise eventually reached was that schooling was compulsory but that religious schools “counted” as official education. By 1889, religious schools were receiving financial support, and full equality between public and private in funding was codified in the constitution of 1917.

In Belgium in 1879 a Liberal government adopted a school reform that (1) reduced local control, stressing that “teachers were State functionaries” and that local authorities had no rights over teachers, (2) ensured “private (Catholic) schools lost all subsidies,” (3) removed from the Communes the choice of adopting a Catholic school to provide basic education, requiring them instead to build and maintain a state school, (4) stopped all ecclesiastical inspection of schools and ecclesiastical guidance in textbook selection, (5) dictated a program of studies for schools, and (6) “stated quite explicitly that in the future all teachers in government subsidized and controlled schools must be trained in State-controlled teacher-training establishments” (Mallison 1963, 232). The strong backlash against this law (dubbed La Loi de malheur, “the law calamitous”), led by Catholic supporters and clergy, led to a defeat of the Liberal party in the elections of 1884 (a defeat from which the party never recovered).

From time immemorial it has been recognized that the most important part of education is the set of beliefs, attitudes, dispositions, and values that young people acquire about themselves and their relationship to the natural, social, and political worlds in which they live. In formal schooling, instruction in skills and the inculcation of beliefs are inextricably mixed: there is no part of the curriculum in which what is being taught and how it is taught are not simultaneously conveying to students appropriate beliefs. While language acquisition is contractible, what languages are taught and in what language instruction is carried out convey important signals about beliefs—for example, children who are not taught in their mother tongue in school are sent a huge message about themselves and their language community. While reading is, on one level, a pure decoding skill, you cannot read without reading something that has meaning, and meaning is nearly always conveying beliefs, explicitly or implicitly. One cannot live in the postmodern world and be unaware that all social sciences are at their roots about beliefs. Those fields, such as mathematics and the physical sciences, that set themselves up as value neutral and claim not to inculcate beliefs are often the most hotly contested in respect to the beliefs they convey. A beliefs-neutral education is a self-negating position.

The historical rise of the modern school was therefore everywhere and always a contest for the control of socialization, with the fact that the inculcation of values was not third-party contractible always taken for granted. French Catholics knew that secular schools would undermine Catholicism, irrespective of any claims to neutrality, and French secularists knew priests who taught in secular schools could not be trusted.

The basic structures of the schooling systems were therefore laid down not by technical consideration of what would lead to the efficient production of skills or by any of the ideas of public economics about externalities and market failures. The differences across countries in their schooling systems are the result of struggles over who could control the socialization of youth and how. The centralization of France, the federalization of Germany, the localism of the United States, and “choice” in Holland were not the result of debates over the relative technical efficacy of these different systems but of the differences between the state and the population in ideas about legitimate socialization.

The Spread of Public Schooling

Inclusive and powerful systems of public schools did not exist anywhere in the world even two centuries ago…and a vigorous use of the historical imagination is needed to understand the transformation caused by the rise of nationalism…. The institutional mountain range that divides the older past from the present is nationalism and its individual peaks and great plateaus are the nation-states that use the school as an instrument of nationalism.

HARRY GEHMAN GOOD AND JAMES DAVID TELLER, A HISTORY OF WESTERN EDUCATION

The main intellectual puzzle of accounts that attempt to explain the rise of schooling is not explaining its rise in the historical developmental successes, such as France, Japan, and the United States. As we saw above, in such cases some simple combination of rising returns on formal schooling as part of an education, increasingly democratic political structures, and the demands of ideological control of socialization (either state-led, perhaps constrained by democracy, or driven by democracy) does the trick.

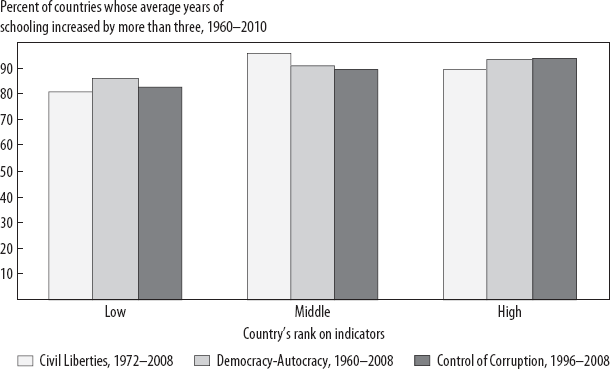

Figure 5-1. Schooling increased massively in nearly all countries, including repressive, autocratic, and corrupt countries.

Source: Author's calculations with Barro-Lee data on years of schooling, POLITY IV for Democracy-Autocracy, ICRG for Control of Corruption, and Freedom House for Civil Liberties (see Data Sources).

The hard thing is explaining the universality of the rise of schooling, in that enrollment is nearly universal in countries that are otherwise complete and abject failures economically, politically, or both (figure 5-1). The puzzle is not why the primary school gross enrollment rate (GER) in peaceful, equal, democratic, prosperous Costa Rica is 110 percent, the puzzle is why it is 113 percent in neighboring Guatemala, which has none of those traits.4 The problem is not explaining a GER of 104 percent in Thailand but why it is 119 percent in neighboring Cambodia. In infamously corrupt Nigeria, the GER is 97 percent; in the borderline “failed state” of Pakistan the GER is 92 percent. The puzzle of schooling is that bad guys do it too.

To explain the common phenomenon across countries of the rise to (almost) universal schooling, mainly through publicly produced spider systems, we need not one but three different narratives, all of which lead to the same outcome (we'll come back to Occam and his razor), which can coexist in various mixes. The three accounts of the rise of modern schooling are:

—Demand, driven by a modernizing economy

—The pure drive for ideological control of socialization

—Isomorphic mimicry (Keeping up with the Joneses)

I take each of these in turn.

Demand, Driven by a Modernizing Economy

Primitive education was a process by which continuity was maintained between parents and children…. Modern education includes a heavy emphasis upon the function of education to create discontinuities—to turn the child of the peasant into a clerk, of the farmer into a lawyer, of the Italian immigrant into an American, of the illiterate into the literate.

MARGARET MEAD, “OUR EDUCATIONAL EMPHASIS IN PRIMITIVE PERSPECTIVE,” 1943

The first narrative about the rise of schooling relates a fundamental shift in the economic activities that increased the private pecuniary returns to schooling. Early work on the economics of education emphasized that in a perfectly stagnant economy, there is no return on formal education (Schultz 1964). In the economy that characterized most of human history, in which daughters did what their mothers did and sons did what their fathers did, so that most of the population held the same occupation generation after generation, and in which technological progress was slow, so that the generations carried on doing the same tasks using roughly the same tools and techniques, education occurred mostly by apprenticeship and was conducted within the household or clan. It is only when technology creates relatively rapid change and the occupational shifts become massive that a monetary demand for anything like formal schooling emerges, because those with higher levels of education earn more money.

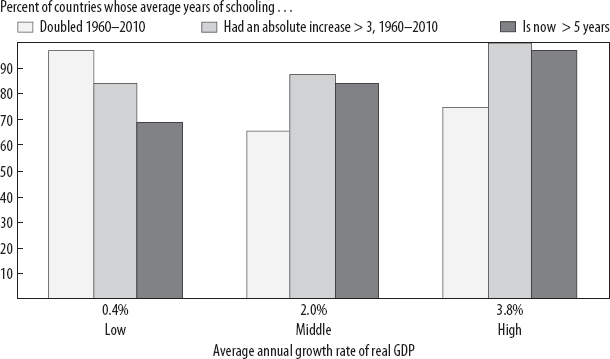

The increased economic returns on education have certainly been a major factor in the expansion of demand for schooling. However, private demand due to economic dynamism does not fully account for the universality of the expansion of schooling. Over the last fifty years schooling has risen massively, in both rapidly growing and economically stagnant economies. Figure 5-2 shows the differences in the growth rate of schooling across countries with low economic growth (less than 0.4 percent per annum), medium growth, and high growth. More than 95 percent of countries that had a low average annual growth rate of real GDP for the period 1960–2010 also saw the years of schooling of their population double. Of course, most of these countries started from a low base, but even in absolute terms, more than 80 percent of the low-growth countries saw their average years of schooling increase by more than three years.

Figure 5-2. Countries in the lowest third of economic growth rates were most likely to double their years of schooling, 1960–2010.

Source: Author's calculations, based on data from Barro and Lee (2010) and Penn World tables.

In this narrative of the rise of schooling, governments play a responsive role. Parents demand more schooling and states, under the pressure of citizens, respond by supplying more of it. This explanation does not explain why governments are responsive by producing rather than financing schooling, but it can explain the rise of the demand for schooling.

Supply Driven, by a Need for Nation-State Control of Socialization

Let me stand a common observation on its head, to create a puzzle, which then points immediately to an answer. The common observation is that many communist states have achieved much higher levels of education than their per capita GDP would predict: places like Cuba are very educated for how poor they are. But stand that on its head. If education drives higher productivity, why is Cuba so poor with such high education? This creates a puzzle. If the expansion of schooling was not driven by a modernizing economy creating incentives for parents and children to become more educated, what accounts for the massive expansions of education, even in the face of economic stagnation, if not retrogression?5

This time it is an expansion in the demand for socialization, but with the causation flowing from demand by the nation-state for the socialization of the student. That is, instead of the student wanting skills and the state directly producing schooling to control the beliefs, in this case the state gets kids into school, even if not motivated by returns on skills, in order to create a set of beliefs.

Think of the “ideology”—a collection of beliefs—that most perfectly justifies a particular regime's control over the state. Now think of the “ideology” children would receive through their education and socialization if they had no formal schooling at all.

If the state's desired ideology and the traditional default ideology are close, that is, if a regime appeals to “traditional” values to legitimate its control of the state, then the regime's need to expand formal public schooling is low and its antipathy toward private schooling is low.

At the other extreme, imagine a regime that legitimates its control of the state on the basis of an ideology and that ideology is new, so that the folk socialization of a nonformal school-based education is unlikely to convey that ideology. In this case the gap between the “public school” socialization and either the “no school” socialization or the “private school” socialization is large and works to the disadvantage of the regime. In such a case we would expect regimes to both push to expand public schooling and exhibit antipathy toward private schooling (which would often, of course, exist as a recourse for parents who wanted to avoid the regime ideology).

There are four examples of predominantly ideological supply-driven situations (many of which blend): Marxist-Leninist/Maoist communist regimes, secular nationalist regimes in countries with Islamic populations, nation-creating states resisting regional or ethnic centrifugal forces, and regimes founded on personal ideologies.

The New Communist Man

That the Marxist-Leninist regimes used the expansion of educational systems as a means of ideological control is not disputed; in fact, it was an explicitly stated objective of those systems. In these cases one can see the tragic extreme of expanding schooling in the absence of any benign motivation on the part of the regime. According to official statistics, the number of children ages eight to fifteen in Ukraine almost doubled from 1928–29 to 1932–33, and enrollment reached 4.5 million. During 1932–33 there was also a combination of a purge of the Ukrainian elite with “nationalist” sympathies and a famine that cost somewhere between three and five million lives. Was Stalin of two minds about Ukraine, expanding schools for benign motives, yet killing, deporting, and confiscating food for malign motives? Of course not. The expansion of schooling, the purges, and the famine had the same objective—a suppression of Ukrainian nationalism and of opposition to Soviet (Stalin's) control.

China is sometimes used as a positive example of a “human development”–led strategy in which investments in human capital created the conditions for the economic take-off under Deng after 1978. In June 1966, schools in China were closed to allow students to take part in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and one of history's grandest experiments in education reform was fully launched. It was not until October 1967 that schools were encouraged to “prepare for the recruitment of new students,” but the reopening of schools went slowly, and when schools were reopened it was not to return to studies. Rather, students were to return to schools to do a better job of “making revolution” and “resume the lesson of class struggle” and “smash the outmoded content and form of teaching” (Chen 1981, 91). In a country that had relied on examinations to choose civil servants for more than a thousand years, all examinations in schools were to be abolished. A return to academic subjects was impossible, if not downright dangerous, for teachers, so the reopened schools focused on ideology “adhering closely to quotations from Mao and songs such as ‘East is Red’ and ‘The Great Helmsman’ ” (Chen 1981, 91) and devoted time to the “half study, half work” approach to schooling. Into this ideologically charged and chaotic system more and more students poured, with the result that “academic secondary” enrollments increased from 9.3 million students in 1956 to 58 million by the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 (Hannum 1999).

Statistical analysis confirms the two obvious points (Pritchett and Viarengo 2008). One-party states that adhered to communist ideologies had much less tolerance for private schooling: the share of secondary education in the private sector in these states in 1990 was essentially zero, compared to roughly 11 percent in multiparty democracies. But at the same time, these states had more total education (adjusted for level of income) than other countries.

Secularists with a Dominant Religion

I have found it impossible to come up with a generalized measure of the difference between a regime's desired ideology and the “no formal schooling” socialization children would receive, but religion provides clear examples of the differences this produces for state tolerance or encouragement of private providers.

In the Middle East, one can distinguish between secularist regimes and the generally more religiously conservative monarchies. Not surprisingly, the secularist regimes have five times lower secondary enrollment rates in private schools than the conservative monarchies (3 percent versus 15 percent).

This reflects similar struggles that happened in Europe and in Latin America, struggles that, as we have seen, have long-term consequences for the structure of schooling. If one compares the South American countries that had become secular versus those that declared Catholicism as their state religion in 1900, even one hundred years later one can see the persistent effect of the greater toleration of private (religious) schooling, with lower private school shares of secondary enrollment in 2000 in those countries that were “secular” in 1900. At the obvious extremes, Mexico, whose 1917 constitution explicitly forbade religious schools,6 today has only 16 percent of secondary students in private schools, in contrast to the 56 percent in private schools in neighboring Guatemala.

Keeping the State Together, Even When It Is Not a Nation

In the postcolonial period, many countries struggled with the fact that their newly controlled states were not (yet) “nation-states”—that is, the territory controlled by the state encompassed more than one potential nation. What had been held together by colonial fiat had to be legitimized as a nation. In Benedict Anderson's (1983) classic phrase, the “imagined community” that made a nation had to be imagined and then encouraged in the imagination of others. Indonesia, for instance, is an archipelago of thousands of islands with hundreds of languages and (at least) dozens of distinct cultures, to which two global religions, Islam and Christianity, arrived at roughly the same time, and hence each has strongholds. As one part of its effort to resist the centrifugal pressures, the government of Indonesia created a national language by imposing its use throughout the centrally controlled schooling system.

It's All about Me (and My Ideology)

In Tanzania in 1967, Julius Kambarage Nyerere, who served as the country's first president and had been an educator prior to entering politics, launched Education for Self Reliance, an ideological remaking of the schooling system. He feared that schooling was producing values that were not consistent with socialism or with the reality that most school-leavers were going to remain and work in agricultural areas. Primary education became the terminal degree for nearly everyone; access to secondary and higher education was incredibly rationed. The primary schooling curriculum was changed to promote more “cooperative” behavior. He also reoriented school studies to be less academic and more integrated with the life of the community. The education plan was an integral part of Nyerere's socialist vision of ujama, in the execution of which the rural population was resettled (voluntarily or otherwise) into organized settlements to better promote delivery of social services and more collective action.

The point of these individual stories about how the interplay of state and traditional ideologies interacted in the evolution of state engagement with schooling is that in nearly every historical narrative, there was some strong contest among alternative socializations of youth that became important in how the schooling system was shaped and what forces drove its expansion.

These first two forces are pretty much garden-variety demand and supply as the driving forces, though of course, the outcome is the match of supply and demand. In the first narrative the causal driver of change is the increase in demand for schooling because parents perceive their children need schooling because of the changing economy and dynamic life conditions. To this incipient demand governments respond with supply (“if there is to be schooling, we must do it”) in order to control socialization. In the second narrative an autonomous shift in the nation-state and in how it is ruled can create a state that pushes supply, even ahead of parental demand, to create a venue for socialization. But in both cases the explanation of government production (or not) of schooling is the state's need for direct control of schooling because instruction in beliefs is not third-party contractible.

Isomorphic Mimicry

The pressures of survival in the natural world are so strong they produce all kinds of unnatural things. The example of the stripes of the scarlet king snake is not unique; the natural world is full of deceit. Predators like leopards have camouflage to look like their background to gain advantage on prey. Prey have camouflage to either hide or blend into the background to avoid predators. Mimicry of all kinds is common.

Among noneconomists who study education, the most widely accepted explanation for why bad countries do the good thing of expanding schooling is that nation-states are embedded in a world system. Isomorphism at the level of the nation-state leads even bad nation-states to want to signal that they are legitimate, full-fledged nation-state members of the world system (e.g., Boli, Ramirez, and Meyers 1985). Hence if nearly all other nation-states are expanding public schooling, usually with functional purposes and with functional schools, then many other nation-states will also expand public schooling, not because of any deep commitment to advancing the well-being of their people but because it is what all other nation-states are doing.

As we saw in the previous chapter, this is potentially a powerful explanation as to why many governments adopted and ran school systems, with no particularly benign motive.

Just So Stories That Just Ain't So

It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.

MARK TWAIN

A man was sailing in a hot air balloon but hit a fog so dense he lost his bearings, could not see the ground, and became hopelessly lost. In a brief moment of clearing he saw another man walking along a road. “Where am I?” he shouted down. “You are up in a balloon,” came the reply. “You must be an economist,” said the man in the balloon. “Exactly correct, but how did you know?” From the balloon: “Because your answer was precisely correct and yet completely unhelpful.”

The noneconomist reader may want to move on as I take up some intramural issues with my disciplinary tribe. Economists have done policy discussions of education a disservice in three distinct ways, each perpetuated by different ideological strands within the profession.

Normative as Positive

One of the most powerful ideas in economics, going back to Adam Smith's invisible hand of the market and progressively subjected to mathematical formalization, is that, under suitable conditions, the equilibrium of a market in which each individual pursues his or her own well-being will result in socially desirable outcomes. Deviations from these strict conditions are common. Economists call them “market failures.” There is an area of economics, sometimes called “welfare” economics or “public economics,” that asks whether, in the face of market failures, it would be possible for someone, say, a “social planner,” to design and implement a policy that would lead to an outcome that would be preferred by everyone. With no restrictions on the instruments available to a social planner, the answer is nearly always yes, the optimal outcome can be reached even with market failures. Classic examples encountered in economics courses are negative externalities in which the smoke from my factory goes into the air and harms others, a harm that I as a factory owner do not “internalize” in my profit-maximizing calculations. But a “social planner” could impose a tax on the production of smoke that, combined with lump sum transfers, could make everyone, including me, the factory owner, better off. So far, so good, and many deep and important insights have come from pursuing this logic.

The problem arises when normative stories become “just so” stories that pretend to be causal accounts of the world, in which the normative analysis of what could, if it were to happen, improve well-being becomes a positive “explanation” of what actually happens. So if we happen to observe that factory smoke is taxed in a situation in which taxing factory smoke would be normatively optimal, one could jump to the conclusion that smoke is taxed because that taxation is optimal.

Nah, I can hear you saying, not really, no one would really make that mistake; you are attacking a straw man. You imagine that no one actually confuses normative, the hypothetical construct of a benevolent social-welfare-maximizing planner, with a real-world description of what the governments of Hastings Banda and Soeharto and Stroessner actually did. Yes, actually, economists do this all the time, particularly with schooling. The World Bank's website on education, meant to “educate” people about the economics of education, in 2000 claimed:

Governments around the world recognize the importance of education for economic and social development and invest large shares of their budgets to education. The reasons for state intervention in the financing of education can be summarized as: High returns, Equity, Externalities, Information asymmetries, Market failure.

Here I note that concepts like “market failures” are given as reasons for state intervention, a positive account of why governments “invest large shares of their budgets to education.” As I have shown elsewhere, none of these normative reasons actually works as a positive account of what governments actually do, but that is probably either obvious or just not that interesting to the noneconomist reader, and not really the point.

The major problem is that there are three ways in which normative as positive, or NAP, accounting goes beyond a mere waste of time for a smallish (a few hundred, perhaps a thousand) number of academics to potentially do intellectual harm in the real world.

First, a narrative in which things are the way they are because that is the optimal choice of an agent who is striving to improve social well-being means that things can only get better in two ways: through an expansion of the resources available or through “technological progress.” This suggests that the two ways to improve the performance of education systems are advocacy (to get the optimizing agent more resources) and research (to create new knowledge for the optimizing agent to use). There is no question that this narrative might have some elements of truth in some places and at some times, but as a general view about the means of improving performance of schooling systems it has absolutely nothing going for it. Besides being suspiciously self-serving about justifying the important role of researchers, this view risks creating complacency, suggesting things are basically right and just need tinkering with.7

Second, and much worse, many of the NAP explanations rationalize government actions in schooling on the premise that governments (the “social planner”) care more about the education of children than the parents do because of the “positive externalities” to schooling. While NAP proponents do not mean it to, this creates an intellectual environment that justifies overriding parents’ needs, demands, and desires in favor of the supposedly more socially attuned objectives of the government. This is not just false as a descriptive model but positively pernicious. (Elsewhere I have argued—see Pritchett 2002 and Pritchett and Viarengo 2008—that there is no feature of real-world schooling systems in developing countries that NAP accurately explains.) These ideas create intellectual legitimacy for taking control out of parents’ hands—something states often want for reasons less than benign. Third, an NAP accounting can easily be stood on its head: one can take a simple empirical observation and then invent the “positive” explanation for it, and really ask whether the proposed explanation fits. We can take as an example the question of this chapter of why schooling systems tend to be so big. Economics has an easy answer: economies of scale. That is, costs are lower in larger systems. If one has to produce an explanation of positive realities that are also normatively attractive, then one gets into doing detective work backward. That is, since we know schooling systems for basic schooling are huge (at the level of nation-state or province) and economies of scale are the positive explanation of hugeness, then even if we don't see them, we know there must be economies of scale.

The key test of whether economies of scale can explain the size of public systems is whether the private sector does the same activity at similar scale. For instance, the state-run post office is a modern marvel of centralization, and when the private sector delivers mail (or packages) it often does so through huge centralized organizations as well. While the U.S. Postal Service has 785,000 employees, United Parcel Service has 425,000 employees and FedEx has 240,000. The centralized organization is amenable to the activity of delivering post and packages, as there are economies of coordination, and delivering the mail can be carried out with just an address: a single piece of hard, easily encoded, third-party-verifiable information about the intended recipient. Everything but the address (name, location) can be invisible to the delivering: whether the address is a huge office building, a tiny box, a mansion, a hovel; whether the addressee is tall or short, nice or mean, rich or poor, or for that matter even a person and not a church or a corporation. The ease with which all of the relevant information can be transmitted, along with economies of scale in coordination, leads postal delivery services to be huge organizations, as large size is productively efficient and organizationally viable—whether public or private.

In contrast, nearly all organizations providing services, especially professional services, are extremely small organizations. The largest law firms in the United States have fewer than four thousand lawyers (the largest in all of Latin America has 444). Most dentists have traditionally worked in practices of one or two dentists. A survey of architects in the United States showed that three quarters worked in practices with five or fewer partners. In occupations or sectors (and even product lines within sectors) in which the quality of the service provided requires detailed adaptation to a specific case, and in which the quality of the service provided is based on information that is complex, difficult to encode, and hard for a third party to verify, then managing organizations with large numbers of employees becomes very difficult. Hence, unless some other positive economies of scale are sufficiently powerful to offset this observation, professional services firms tend to be small, with relationships handled without complex and rigid rules or organizational policies (including human resource policies), with performance assessed directly, and with high-powered incentives easier to create (such as small business owners).

The question is, is schooling more like delivering the mail or more like practicing dentistry? It is pretty obvious that when the private sector provides quality education, there are few, if any, economies of scale, and organizational expansion is very, very, hard. Harvard University, four hundred years into its existence, still has only about six thousand undergraduate students. There is enormous evidence that, in the activity of imparting instruction, economies of scale are just not achievable, which is obvious as mom-and-pop, one-school firms easily compete head-to-head with large schooling systems.

Vouchers: Settling for Pyrrhic over Victory

No one susceptible to economic reasoning can read the clarion call for vouchers in Milton Friedman's classic Capitalism and Freedom and not be persuaded. Persuaded, that is, that if it were the case that the objective of state engagement in schooling was the promotion of contractible skills, then the use of “money follows the student” schemes—or, more crudely, vouchers—would be a more effective policy than governments directly producing schooling. Over the years objections have been raised to arguments for vouchers—that they would lead to segregation, that they would perpetuate inequality. But as Caroline Hoxby's (2001) paper shows, with even more technical sophistication than Friedman, “Anything Q can do P can do better.” That is, any goal that government supply can accomplish by increasing the quantities (Q) of schooling available (or targeting that Q to regions or races) could be accomplished more effectively by a suitably designed price (P) scheme. But that “anything” that P can do must be third-party contractible, otherwise the P incentive schemes can be undermined.

The problem with arguments for vouchers is that, just as Samuel Goldwyn explained the fate of his intended blockbuster, “They stayed away in droves.” Modern schooling systems have been around for at least a hundred years. There are now almost two hundred countries. With all those chances for countries to adopt a voucher system (as opposed to portable scholarships as a minor frill in a fundamentally spider system), there have been precious few successes. Holland has a “money follows the student” system with parental choice, but for reasons detailed above that owe nothing to Professor Friedman or a belief in free markets. Besides moves in that direction by a few ex-communist countries immediately following the transition, such as the Czech Republic, Chile in 1981 is the only definitive adopter of a voucher-like system.8

Every time a voucher scheme has been put before the voters in the United States, it has been defeated. In this regard, Utah is particularly remarkable. Utah is one of America's consistently most conservative states (Obama got only a third of the state's general election vote in 2008, for instance). For this and other reasons Utah was believed by voucher advocates to be a state potentially receptive to the voucher program (Schaeffer 2007). However, when Utah voters had to decide whether to adopt the country's first statewide school voucher program, which would have been open to anyone, an overwhelming majority of Utah's voters, 62 percent, rejected it. The proposed law lost in every county. A “conservative” political agenda that cannot win in Utah cannot win.

Good Stories, Overextended

The last danger of economic thinking is that good stories of specific cases, particularly when they can be fleshed out with mathematics and provided some empirical support, too quickly become the accepted explanation and are too easily extended in terms of both the range of cases they are held to explain and the range of phenomena they are held to encompass. Some excellent works on the rise of education address the positive political economy in an interesting and theoretically plausible way (not, that is, the simplistic NAP accounting). The economic historian Peter Lindert's Growing Public (2004) is an excellent account of the historical rise in social spending in OECD countries. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2000) have an intriguing model explaining the rise of schooling in the West as a bargaining game between “elites” and “the masses.” Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz (2008) have written a monumental empirical account of the rise of schooling in the United States. Theorists such as Dennis Epple and Ricard Romano (1996) have constructed voting models that can generate a positive political economy of public production. None of these scholars would claim or have claimed that their work generalizes to explain the rise or features of schooling systems more broadly. Yet exactly such a casual overgeneralization from the history of the UK or the United States to completely different settings happens all too often.

The Beatles. Espionage and double agents. Church organists. Referenda in Utah. Fun stuff, you might say, but what does it have to do with reforming primary education in India or Brazil or Tanzania or Afghanistan?

There is a Russian fable about a bird that left too late on her southward migration and got caught in a snowstorm, could not fly, and was freezing to death. Along came a sympathetic cow, who said, “There is not much I can do for you, but my poop is warm and if you were inside my fresh pile for a minute you could warm up enough to fly on.” So they tried that, and it worked. The bird warmed up, started stretching her wings. Just as she was about to fly a wolf came along, snatched her out of the pile, wiped her off, and gulped her down. The moral of the story is that not everyone who puts you in a steaming pile is your enemy, and not everyone who takes you out of one is your friend.

Just because schooling is a great thing for a child, perhaps even a fundamental human right, does not mean that those who engage in it do so for entirely benign motivations or in the right way.

The expansion to universal coverage has been universally successful because it has met a universal range of needs of states—and of the political regimes that control them.

The systems are big, but the part of education for which big is better is the control of socialization. The size of schooling systems has historically been determined by the size of the need for control of socialization.

Schooling is publicly produced rather than publicly supported or financed because the inculcation of belief is not third-party contractible and because public control of socialization requires some direct control of producers.

You cannot search if you are convinced you have already found what you need. Nothing about the current schooling systems in developing countries was designed or adopted for the purpose of reaching learning goals. It would be extremely unlikely that a hippopotamus, an animal whose evolutionary design was premised on living in large bodies of water, just so happened to be the perfect animal to cross the desert in a caravan. The spider systems we have today were designed in the nineteenth century and adapted and adopted in the twentieth century to meet a certain set of demands: to prepare workers for a transition out of agriculture, to build nations to support states, and to legitimate the regimes that controlled those states. It would be extraordinary indeed if those spiders just so happened to be systems designed for the learning and educational challenges the youth of the twenty-first century will face.

1. The material in this section draws on earlier work of mine (Pritchett 2002; Pritchett and Viarengo 2008).

2. While many think that economists have been intellectually influential, the most cited academic economist in Google Scholar, Gary Becker, has half the citations of Foucault.

3. Passin (1965, 88–89).

4. All figures on gross enrollment rates are from the EFA monitoring report of 2010 (Education for All 2010).

5. This section is based primarily on a paper written jointly with Martina Viarengo (Pritchett and Viarengo 2008). It builds on earlier work by Lott (1999) and Kremer and Sarychev (1998).

6. Article 3, section IV: “Religious corporations…shall not in any way participate in institutions giving elementary, secondary and normal education.”

7. As we saw in chapter 3, much of the research done under the rubric of NAP examining the educational production function (the school and classroom correlates of student learning) makes rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic look like rational prioritization.

8. Even in the case of Chile, a country where Chicago School economists had great influence over policy, it is obvious that the real reason behind the switch was not the control of socialization, but this time in reverse. Chile's teachers’ unions were at the time dominated by hard-line, left-wing ideologists. It is plausible that Pinochet anticipated, correctly, that nearly all the move out of public schools would be into Catholic-operated schools, with an ideological orientation typically much more sympathetic to his views (and much less sympathetic to Marxism). By privatizing the school system he effectively moved a quarter of all children outside the reach of the public sector teachers’ unions.