CHAPTER 5

Underemployment

The most common way of measuring underemployment is to calculate the number and share of involuntary part-timers (IPT) in total employment. This is a relatively crude measure that only captures the number of part-time workers wishing to extend their hours. It carries no information on the number of additional hours these workers would prefer or on whether some other workers would prefer to reduce their hours. It turns out that there are significant numbers of the overemployed who want fewer hours.

The use of a measure of underemployment based solely on part-timers who can’t find full-time jobs reflects the lack of alternatives, particularly in the United States. In Europe, involuntary part-timers are described as part-timers who want full-time jobs (PTWFT), whereas in the United States they are described as part-time for economic reasons (PTFER). In Europe, statistics on PTWFT are obtained from the individual-level European Labor Force Surveys (EULFS) and in the United States on PTFER from the Current Population Survey. I treat these measures analogously. Monthly data on these measures are published for the United States and the UK; quarterly data are available for Europe.

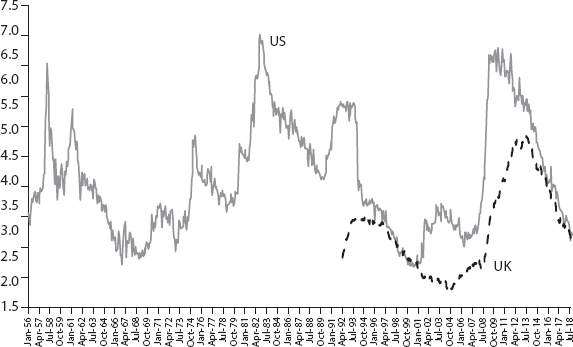

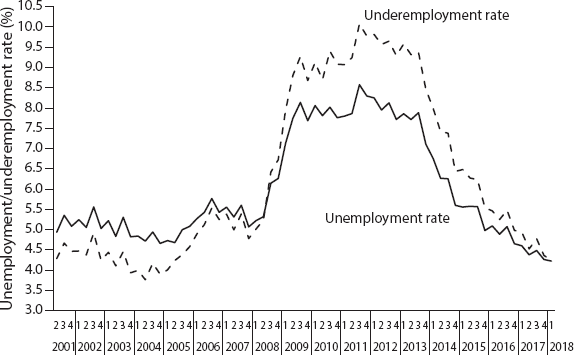

Figure 5.1 plots PTFER and PTWFT for the United States and the UK, respectively, in each case expressed as a proportion of total employment that David Bell and I have termed U7 (Bell and Blanchflower, forthcoming).

Monthly data are available for the United States from May 1955 through June 2018 and for the UK from April 1992 through April 2018. First the data for the United States show strong cyclicality with peaks of 6.3 percent in March 1958 and 6.7 percent in March 2010. The UK rate peaked at 4.9 percent in April 2013 and in the latest data for January 2019 is 3.3 percent, having jumped 490,000 on the month. In the United States the post-2000 low was 2.3 percent in July 2000 while in the UK it was 1.9 percent in December 2004 and in the latest data release for October 2018 is 3 percent. In both the UK and the United States rates peaked after the Great Recession and fell back but have not returned to pre-recession levels. This rise and subsequent fall in U7, as I document in this chapter, were also the case in other advanced countries. Underemployment is an additional amount of labor market slack over and above the unemployment rate.

Figure 5.1. Involuntary part-timers as percentage of workforce. Sources: BLS and ONS.

Policymakers Have Spotted the Rise in Underemployment

In the past underemployment tracked unemployment closely, but since the Great Recession that has not been the case. At the beginning of 2017 the New York Times editorial board argued as follows:

Even now, the Fed should continue to keep rates as low as possible, for as long as possible, to help bring down underemployment: The number of working people who cannot find full-time hours remains elevated even as unemployment has declined.1

The minutes of the FOMC meeting in December 2016 argued that

some participants saw the possibility that an extended period during which labor markets remained relatively tight could continue to shrink remaining margins of underutilization, including the still-high level of prime-age workers outside the labor force and elevated levels of involuntary part-time employment and long-duration unemployment.2

The European Central Bank, in its June 2016 Economic Bulletin No. 4, got in on the act too:

At the euro area level, the growth in part-time employment seems to have been driven to a significant extent by employers’ preference for this type of contract. More than half of the increase in part-time employment since the first quarter of 2008 seems to reflect decisions taken on a voluntary basis, as workers willingly took advantage of new part-time opportunities. However, almost half is due to a rise in “underemployment” as workers involuntarily accepted part-t ime employment, although they would have liked to work more.3

Ignazio Visco, governor of the Bank of Italy, concurred on November 11, 2015:

It is now quite generally held that the “potential” growth rate too has been lowered by the reduction in investment and the very high levels of long-term unemployment and underemployment.4

Chapter 2 of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook for October 2017 looked at recent wage dynamics. They concluded that “the bulk of the wage slowdown can be explained by labor market slack (both headline unemployment and underutilization of labor in the form of involuntary part-time employment), inflation expectations, and trend productivity growth. While involuntary part-time employment may have helped support labor force participation and facilitated stronger engagement with the workplace than the alternative of unemployment, it also appears to have weakened wage growth” (2017, 1). The IMF found that in comparing the years since 2008 with 2000–2007 in economies where unemployment rates are still appreciably above their averages before the Great Recession, conventional measures of labor market slack can account for about half of the slowdown, with involuntary part-time employment acting as a further significant drag on wages.

In economies where unemployment rates are now below their averages before the Great Recession and measured slack appears low, slow productivity growth can account for about two-thirds of the slowdown in nominal wage growth since 2007. Even in these economies, the report suggests involuntary part-time employment “appears to be weighing on wage growth.” The report says, “Subdued nominal wage growth has occurred in a context of a higher rate of involuntary part-time employment, an increased share of temporary employment contracts, and a reduction in hours per worker.” They are right when they argue that “market slack may therefore be larger than suggested by headline unemployment rates” (2017, 85).

Dennis Lockhart, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, gave a speech called “A Potentially Momentous Year for Policy” in Atlanta on January 12, 2015, in which he argued that “the recent evidence on wages has been mixed. A number of measures of wage growth remained well below historical norms throughout most of last year, while others did tick up slightly in the second and third quarters. Based on research, my team has advanced the thesis that the elevated number of people working part-time involuntarily is restraining wage growth.”5 It turns out that is right, and I will return to the issue of the extent to which underemployment impacts wages.

Underemployment means workers are being pushed into part-time jobs when they would like full-time jobs—so-called involuntary part-timers. It can also mean that workers who voluntarily choose to be part-time or who are full-time have fewer hours than they would like. And the desire for a change in hours of voluntary part-timers and full-timers, along with involuntary part-timers, varies over time with the cycle in expected ways. In bad times workers of all three types want more hours and in good times they want less. At the same time, there are workers who feel overworked and would like fewer hours (overemployment). Simply using involuntary parttimers ignores how much voluntary part-timers and full-timers want to change their hours.

The Literature Says Firms Change Worker Utilization Rates as Product Demand Changes

When the labor market is fully functioning, there are different jobs on offer, so workers can find jobs with the right number of hours to suit them. In the post-recession world, many workers and especially new entrants are hours constrained. They would take more hours at the going wage rate. This wouldn’t happen if labor markets were at full employment. The levels of underemployment currently being experienced, even though they are below their recent peaks, are still higher than they have ever been at such low unemployment rates. Underemployment has to be added to unemployment to get a true measure of labor market slack. It should be said, though, that we do have evidence from the UK that in the years 2001–8, on the net, workers in the UK wanted fewer hours not more, so they were overemployed.

If aggregate demand were higher, our data suggest that more wage-hour combinations would be available that include extra hours, which would likely improve welfare and well-being. Low demand reduces the availability of such choices and generates underemployment. Given the fact that the data we present suggest that workers are prepared to work more hours at the going wage, a package with a higher number of hours in it would likely be profitable for firms.

What theoretical backing can we give to our claims to observe underemployment and overemployment, when the so-called “canonical” model of Pencavel (1986) suggests that workers are free to choose their hours of work, given the wage rate? In answer to this, first, we note that more recently Pencavel (2016) himself acknowledged that this model where workers select their hours, dominant in the literature since Lewis (1957), neglects the role of employer preferences in hours determination.6 Even though Lewis himself stepped back from this position (1969), acknowledging that the preferences of employers are neglected in the canonical model, the assumption that workers select from a continuum of hours, while treating the wage rate as exogenous, continues to dominate research and teaching. This approach persists in economics, even though aggregate hours fluctuate in response to changes in demand and the organization of production requires employers to place some restrictions on working time (e.g., to ensure that a production line is fully staffed).

Some authors, acknowledging that observed hours and wage combinations reflect both supply and demand influences, have sought to identify these effects empirically. Feldstein (1967) and Rosen (1969) attempted to identify the supply and demand for worker hours using industry variation, with limited success. Pencavel (2016) questions why the issue of the identification of supply and demand for hours has been neglected for the last forty years. To put it technically, this literature weakens the assumption that workers are invariably located along their individual supply curves. The evidence suggests that large numbers of workers are off their labor supply curves.

This argument is reinforced by the literature that focuses on how firms adjust to a positive output shock, which dates back to the 1960s and 1970s.7 Hart and Sharot, for example, argued that their results “hinge on the proposition that firms achieve short-run changes in labor requirements by varying their worker utilization rates, whereas … the response of employment is more sluggish and long-term” (1978, 307). Of course, the same applies to a negative shock.

Hart (2017) has noted that the peak-to-trough percentage change in hours in the Great Recession was greater than in employment. GDP fell in the UK by 6.3 percent and by 6.6 percent, peak to trough, in Germany. He notes that employment in the UK fell by a relatively modest 2.3 percent, while person-hours changed more, with a 4.3 percent drop. Germany’s fall in employment was a trivial 0.5 percent, while that of person-hours was a much larger 3.4 percent. The U.S. GDP drop was not quite as severe, at 4.1 percent, but employment and person-hours reductions were considerably greater, at 5.6 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively. The three countries experienced a decrease in peak person-hours that preceded that of employment by at least one quarter.

Hart concludes as follows: “During economic downturns, adjusting person-hours contributes to wage-earnings losses among workers whose actual hours of work fall short of their desired hours. However, the costs of not achieving output requirements in a relatively speedy manner—associated with shortfalls or excesses in the production of goods and services—are likely to be considerably greater. As such, the response patterns of hours compared to employment during demand shocks provide substantial net benefits” (2017).

A key element of Hart’s analysis is the relative costs of varying hours and employment. Where hiring, firing, and training costs are high, employers are more likely to rely on the internal labor market. Where they are low, there is likely to be more job turnover, implying greater reliance on the external labor market. This does not seem to be a situation in which employees are selecting a utility-maximizing combination of real wage and leisure; rather, it suggests workers’ hours preferences being overridden in the interests of firm profitability.

Another version of this argument is that a firm might have some fully employed but not underemployed workers and some underemployed workers, the latter of whom may be a kind of reserve army that permits the firm to give lower raises to the fully employed. The very existence of underemployed workers at a firm alongside those with acceptable hours may well exert more downward wage pressure than would the unemployed.

For example, for unemployed workers to restrain a firm’s wage increases, the firm has to know about the unemployed workers; however, underemployed workers are already there but must communicate their willingness to work longer hours at perhaps reduced wage rates. That presumably isn’t hard given they are prepared to express such a willingness to a survey interviewer. It is also less costly for a firm to increase worker hours than it is to hire new workers. There seems to be no workplace-level analysis that would tell us the extent to which there is a mix of workers who are content with their hours at a workplace or if the underemployed group together in certain firms.

However, if employers are monopsonistic, they may be able to vary workers’ hours in response to fluctuations in demand even if there is little joint investment in firm-specific skills.8 Hours variations are invariably less expensive than rescaling the workforce, and firms may use such variations when they perceive the probability of inefficient separations is low. Bhaskar, Manning, and To (2002) suggest a number of explanations as to why labor markets are typically “thin,” giving employers a degree of market power.

Manning, while also lamenting the preeminence of the canonical model, argues that under monopsony, utility-maximizing employees may be displaced from their supply curve and would express a desire to increase or decrease their current hours at the current wage rate (2003, 228). Using data from the British Household Panel Survey for the period 1991–98, he shows that the desire to reduce hours substantially exceeded desired hours increases. This finding is consistent with David Bell’s and my analysis (Bell and Blanchflower 2018b) using the UK Labor Force Survey (UKLFS) for the early part of the following decade, but we find a subsequent reversal after the Great Recession.

One consequence may be that workers are forced to agree to contracts that give employers rights to vary working time on short notice without changing pay rates. Azar and colleagues (2017) show that product market concentration is high, and increasing concentration is associated with lower wages such that there is a negative correlation between labor market concentration and average posted wages in that market. Using data from the employment website CareerBuilder.com, they calculate labor market concentration for over 8,000 geographic-occupational labor markets in the United States. They show that going from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile in concentration is associated with a 15–25 percent decline in posted wages, suggesting that concentration increases labor market power.

Underemployment is an additional labor resource that can be used by firms when demand rises. The fact that underemployment existed in 2017 at levels much higher than existed pre-recession helps explain why there is weak wage growth. If labor demand were adequate, it would inevitably increase the hours of those who desired more, especially as this is likely a more cost-effective response than hiring more people.

One other thing that does tend to happen in a recession is that young people enter the job market on a lower rung on the jobs pyramid than they would have in good times.9 College graduates take the jobs that would previously be taken by high school graduates and so on. This is especially hard in current circumstances, when college is so expensive and many are carrying high levels of student debt. This adds to the difficulty of striking out on one’s own without the bank of mom and dad. This should be considered another form of labor underutilization. The concern is that young people feel they are overeducated, though the extent of overeducation is disputed in the literature. Wilkins and Wooden (2011) provide a good summary.

Cajner and coauthors (2014) concur that the rise in involuntary part-time employment is dominantly cyclical. They argue that although the number of persons working part-time involuntarily remains unusually high, this primarily reflects continued weak labor market conditions and the share of part-time employment will likely diminish as the labor market improves.

Underemployed individuals are significantly more likely to be “struggling” (54%) than employed Americans (38%), based on data from the Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index. Worry and stress are pervasive among the underemployed. Nearly half said they experienced worry the day before the survey compared with 29 percent of the employed. The underemployed are also more likely than the employed to report experiencing stress and sadness and almost twice as likely to have been told by a doctor or nurse that they suffer from depression (21% versus 12% of employed Americans).

A San Francisco Fed study confirmed that the PTFER depends heavily on cyclical variation in labor market conditions.10 However, the study also identified slower-moving market factors, reflected mainly in industry employment shares and population demographics, which account for ongoing elevation in PTFER despite the cyclical recovery in the labor market. These market or structural factors account for about a percentage point or more of the elevated PTFER share of total employment through 2014. The contribution of these factors declined only slightly during the recovery period following the recession. The study’s results suggest that the incidence of PTFER employment may remain well above its pre-recession lows as the labor market expansion continues.

There is also a suggestion that employers’ anticipation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health benefit mandate explains almost all the rise in PTFER. Using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) between 1994 and 2015, Even and Macpherson (2016) find that PTFER employment in 2015 was higher than predicted based on economic conditions and the composition of jobs and workers in the labor market. Importantly, they find that the increase in the probability of involuntary part-time employment since passage of the ACA has been greatest in the occupations with a larger share of workers affected by the mandate. Their estimates suggest that up to 700,000 additional workers without a college degree between the ages of 19 and 64 are in PTFER employment due to the ACA employer mandate.

The Behavior of the Underemployed

There is a growing literature on the behavior of the underemployed. Valletta, Bengali, and van der List (2018) found that persistent market-level forces, most notably changing industry composition, explain sustained elevation in the rate of involuntary part-time work in the United States. Borowczyk-Martins and Lalé (2016) compare transitions between full- and part-time work including involuntary part-time work in the UK and the United States. In a later article (2018) the same authors show that involuntary part-time work generates lower welfare losses relative to unemployment. This finding relies critically on the much higher probability of return to full-time employment from part-time work, especially at the same employer. They interpret it as a premium in access to full-time work available to involuntary part-time workers.

Feldman (1996) treated “underemployment” more broadly, incorporating education, work duties, field of employment, wages, and permanence of the job and includes a mismatch between education and training. He also suggested that underemployment may be a continuous as well as a dichotomous variable. I do not attempt to extend into these other dimensions of underemployment but rather focus on extending measures such as PTWFT and PTFER that treat underemployment as a dichotomous variable.

Interestingly, Cajner and coauthors (2014) found that one-third of the increase in part-time employment for economic reasons in the United States during the recession represented a shift from voluntary part-time to involuntary part-time employment. They speculate that this merely represents a measurement issue: for example, in times with a weak labor market, CPS respondents became more likely to attribute their part-time hours to economic reasons than to non-economic reasons (e.g., family obligations or other personal reasons). On the other hand, they argue it could be that the increased flow from voluntary to involuntary part-time work during the recession represented a real behavioral change: for example, if a household’s primary earner experienced a spell of unemployment, the secondary earner, who had previously been working part-time for non-economic reasons, might have wished to work longer hours and thus reported working part-time for economic reasons.

Golden (2016) reports that involuntary part-time work and its growth in the United States are concentrated in several industries that more intensively use part-time work, specifically, retail and leisure and hospitality. The retail trade (stores, car dealers, etc.) and the leisure and hospitality industries (hotels, restaurants, and the like) contributed well over half (63.2 percent) of the growth of all part-time employment since 2007 and 54.3 percent of the growth of involuntary part-time employment. These two industries, together with educational and health services and professional and business services, account for the entire growth of part-time employment and 85 percent of the growth of involuntary part-time employment from 2007 to 2015.

There is evidence that involuntary part-timers are disproportionately young, less educated, and minorities. Valletta, Bengali, and van der List (2018) reported that in the United States, men and women under the age of 24, the single, the least educated, blacks and Hispanics, and the unincorporated self-employed are most likely to be IPT. Glauber (2017) noted that workers without a high school degree are more likely to be IPT. Eurofound (2017) reported on the distribution of involuntary part-time work across the EU28 in 2015, finding that they were disproportionately female, young, less educated, and on temporary contracts and in elementary occupations.

There are composition effects by adding more involuntary part-time workers because they suffer a wage penalty. Golden (2016) found that among those who are paid by the hour in the United States, voluntary part-time workers earned $15.61 per hour on average compared with only $15.11 for those working part-time involuntarily. Among those who could “find only part-time work,” their hourly earnings were even lower, $14.53. In Bell and Blanchflower 2018a, using UKLFS data, we found that individuals who reported that they wanted more hours, over and above whether they were PTWFT, had lower wages. Individuals who were PTWFT had lower hourly wages than voluntary part-timers and full-timers. Veliziotis and coauthors (2015) found the same for the UK and also reported the same result for Greece. This implies that wages will be depressed the greater the willingness of workers to provide more hours at the going wage rate. Part-timers who want extra hours are paid less than part-timers who are content with their hours. It seems that having workers in jobs where they want more hours keeps wages down as they accept lower pay, conditional on their characteristics. Underemployment impacts wages.

Glauber (2017) has noted that involuntary part-time workers in the United States are more than five times more likely than full-time workers to live in poverty. She also notes that they earn 19 percent less per hour than full-time workers in similar positions. Women experienced a 14 percent wage penalty for involuntary part-time employment, men 21 percent. These wage penalties are net of differences in workers’ occupations, industries, regional and metropolitan areas of residence, educational attainment, and age. So being underemployed conveys a wage penalty.

Sum and Khatiwada (2010) estimate that the lost earnings in 2009 Q4, when there were nearly 9 million PTFER, compared with 2007 Q4, when there were around 4.2 million, yields an aggregate value of slightly under $68 billion in lost earnings. All told, they calculate the combined aggregate annualized earnings, payroll tax, and other non-wage compensation losses associated with higher levels of underemployment at an estimated $78 billion. They note that the lower-income groups of underemployed workers especially are more likely to depend on in-kind transfers such as food stamps, rental subsidies, and Medicaid to support themselves and their families, thereby imposing fiscal costs on the rest of the taxpaying public.

Larrimore and coauthors reported that in the United States the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Decision Making showed that more than one-third of non-retirees working part-time for economic reasons in 2017 had an irregular work schedule set by their employer.11 One-quarter of non-retired individuals working part-time for non-economic reasons, and 12 percent of full-time workers, have such a schedule. This, the authors suggest, means that many of the part-time workers who would potentially work more hours and thus are not currently at their full employment also face the challenge of unpredictable hours. As another sign of differences in employees’ status, only 3 in 10 of those working part-time for economic reasons received a raise in the previous year versus more than half of full-time workers.

The Evidence on Underemployment

By the start of the Great Recession in December 2007 in the United States and April 2008 in the UK, involuntary part-time employment was off its lows, both in levels and rates, and then it climbed fast. The number of PTFER in the United States hit a high of 9.25 million in September 2010, up from a low of 3.14 million in July 2000 and 4.85 million in January 2008. U7 reached a high of 6.4 percent at the peak in December 2010. This compares to a low of 3.1 million or 2.3 percent of employment in July 2000 and 2.7 percent in April 2006. The latest data for October 2018 show 4.62 million with a U7 of 2.95 percent.

The number of workers who were PTWFT in the UK was as low as 555,000 in January 2003, and 671,000 in April 2008, rising to a peak of 1.46 million in June 2013. As a percentage of employment in the UK, PTWFT now also represents 2.9 percent of total employment; it rose to a peak rate of 4.88 percent in June 2013 versus a low of 1.87 percent in December 2004. In the latest data there were 916,000 workers in August 2018 who were PTWFT, giving a U7 rate of 2.83 percent.

The numbers of PTFER are large as compared, for example, to the number of unemployed people, which in the latest data for the United States in January 2019 is 6.5 million while in the UK in October 2018 there were 1.38 million unemployed. In January 2019 there were around 5.1 million PTFER in the United States, down from a peak of over 9 million in March 2009, or three-quarters of the unemployment stock. In contrast they are around two-thirds of the unemployment stock in the UK. Thus, the additional level of labor market underutilization they represent is substantial.

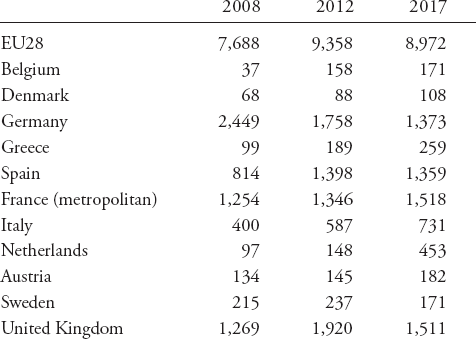

The European Statistical Office Eurostat reports annually a more expansive definition of underemployment among part-timers than U7. It reports data on the number—and the rate as a proportion of employment—of underemployed part-time workers who want more hours.12 That includes not only part-timers who say they want full-time jobs but also part-timers who don’t want full-time jobs but want more hours. As a consequence the numbers they report are larger than using PTFER and the rates they report are higher than U7. The Eurostat numbers across ten major European countries are as below for 2008, 2012, and 2017, in thousands. For the UK the numbers reached a peak of 1.92 million in 2012 and then fell back in 2017 to 1.51 million. This contrasts with an average for U7 published by the ONS of PTFER of only 1.45 million and 1.02 million, respectively, on those two dates.

In nine of the eleven countries the numbers rose from 2008 to 2012 and then fell back and in 2017 were above 2008 levels. The exceptions are Germany, which saw a steady fall, and Sweden, which had a pickup but the 2017 number was below the 2008 number.

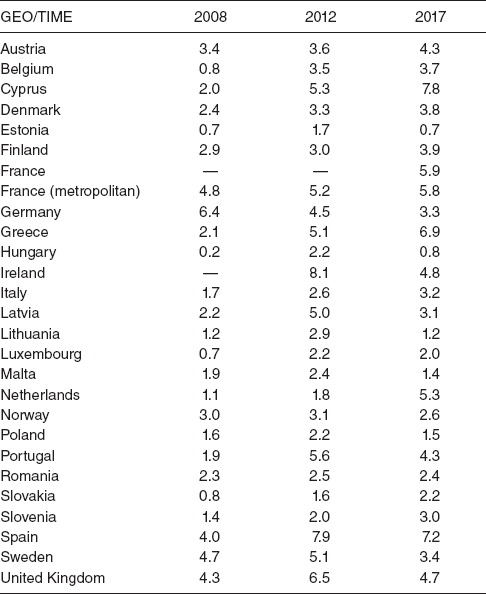

Table 5.1. Underemployed Part-Time Workers Who Would Prefer to Work More Hours as Percentage of Employment (Ages 15–74)

Source: Bell and Blanchflower, forthcoming.

In several A10 East European countries, which had large outward migration flows, especially to the UK—Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia—the numbers in 2016 were little different from those in 2008. If you wanted more hours and you lived in an A10 Accession country, you moved westward, especially to the UK.

Table 5.1 reports underemployment rates based on the numbers reported above for part-timers who want more hours, whether they want full-time jobs or not, expressed as a proportion of total employment for twenty-six countries for 2008, 2012, and 2017. Rates spiked as high as 7.9 percent in Spain and 8.1 percent in Ireland in 2012. In Germany, Norway, and Sweden the 2017 rate is lower than the 2008 rate.

Countries with high unemployment rates like Spain and Greece even in 2017 have high Eurostat underemployment rates. Italy has a relatively low rate given they have such high unemployment rates of over 10 percent. The Netherlands has a noticeably high PTFER in 2017 even though the unemployment rate is 4.9 percent. Some of these contrasts reflect structural differences in national labor markets. In 2017, 46.6 percent of employment in the Netherlands was part-time, while in Portugal and Poland the equivalent rates were substantially lower at 8.6 percent and 8.3 percent, respectively. These differences in the share of part-timers in total employment obviously constrain possible variation in the underemployment rate derived from reports of part-timers, without necessarily fully reflecting differences in labor market slack.

Of note also is that the rise in U7 has accompanied only small changes in average hours worked in both the United States and the UK. In the U.S. private sector, average weekly hours, according to the BLS, were 34.4 in January 2008 versus 34.5 in January 2019. For production and non-supervisory workers, it was unchanged at 33.7 on both dates. In the UK, average actual hours at the start of the recession in March–May 2008 were 37.1 for full-timers and 15.6 for part-timers. This compares to 37.1 and 16.3, respectively, for September–November 2018. Overall average actual hours were 32.0 at both dates. In Germany average hours declined slightly from 35.6 to 35.2. Usual weekly hours fell in the European Union, according to Eurostat, from 37.9 in 2008 to 37.1 in 2016.

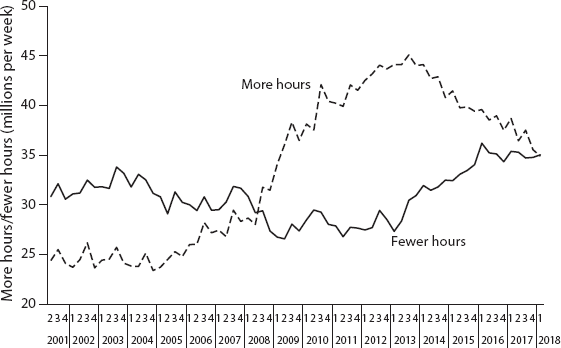

The Bell/Blanchflower Underemployment Index

In a series of papers David Bell and I used data from the UKLFS to show that measuring underemployment using the number of part-time workers who want full-time jobs does not fully capture the extent of worker dissatisfaction with currently contracted hours.13 This is due to its focus on a particular group of workers—involuntary part-timers—rather than all workers. Eurostat’s coverage inclusion of voluntary part-timers who want more hours but don’t want a full-time job is an obvious improvement, but it doesn’t take account of the desires of full-timers to change their hours. It turns out that, over the Great Recession years and subsequently, not only do involuntary part-timers who say they would prefer full-time jobs appear to be underemployed but so also do voluntary part-timers who wish to remain part-time and some full-timers.14 Some workers, mostly full-timers, say they would like to work fewer hours, which also varies over time, both in terms of how many workers report this and the aggregate number of hours they report. We can use these data to determine who is overemployed and who is underemployed.

In the UKLFS, workers report whether they would like to change their hours at the going wage rate and how many extra or fewer hours they would like to work. A desired hours variable can be constructed for each individual. It is set to zero for workers who are content with their current hours. It is negative for those who wish to reduce their hours (the overemployed) and positive for those who want more hours (the underemployed). Equivalent questions are asked in the European Labor Force Survey (EULFS) in twenty-five countries including three non-EU countries—Switzerland, Iceland, and Norway—and the UK.15 We do not have microdata on Bulgaria, Slovenia, Slovakia, or the Czech Republic. None of the major U.S. surveys asks workers whether they wish to increase or decrease their hours. Hence the calculations that we report below are not available for the United States. We use annual data for European countries rather than quarterly data for the UK to avoid having to calculate rather complicated seasonal adjustments by country.

Our underemployment measure is more general than the unemployment rate because it is affected by the willingness of current workers to vary their hours at the current pay rate—underemployment. For any given unemployment rate, a higher underemployment index implies that reductions in unemployment will be more difficult to achieve because existing workers are seeking more hours—there is excess capacity in the internal labor market. We define our underemployment index in hours rather than people space.

Our index gives a more complete picture of excess demand or excess supply in the labor market than does the unemployment rate. It may also offer advantages over the unemployment rate as a means of calibrating the output gap. It is not affected by equal-sized increases and reductions in desired hours. If the underemployment index is high relative to the unemployment rate and there is an upturn in demand, cost-minimizing producers will offer existing workers longer hours, thus avoiding recruitment costs and the costs of uncertainty associated with new hires. Plus, the unemployment rate will not fall so rapidly in a recovery if the underemployment index is relatively high at the start of the recovery. This is what may have happened in the 1980s in the United States and in the post–Great Recession period.

We also use the EULFS microdata to estimate aggregate employment, unemployment, and average hours of work. All of these statistics are converted to national aggregates using weights supplied with the EULFS. We include the employed, self-employed, family workers, and those on government schemes when calculating total employment and average working hours. Together these calculations provide all of the components necessary to create our underemployment index.

Note that unemployment rates peaked in most countries around 2013. They were especially high in Greece and Spain, where they reached over 25 percent. The annual unemployment rate peaked between 15 and 20 percent in Estonia, Ireland, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, and Portugal. In the UK it peaked at 8.1 percent compared with 9.6 percent in the United States. Poland, which had seen an unemployment rate of 20 percent in 2002, saw a steady fall in its rate after its accession to the EU in 2004. Other Accession countries—both the A8 that joined in 2004 and the A2 that joined in 2007—saw much lower unemployment rates in 2017 than prior to the Great Recession.16 By 2017 over 2.65 million people from the A8 and around one million from the A2 had registered to work in the UK.17 According to the OECD the annual unemployment rate peaked in Canada at 8.4 percent in 2009 and at 6.1 percent in Australia in both 2014 and 2015, at 6.4 percent in New Zealand in 2012, and at 3.7 percent in Japan in 2010, which is the same level it reached in 2016 and 2017.18

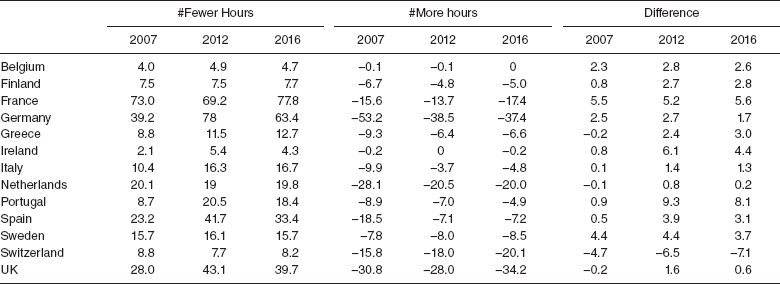

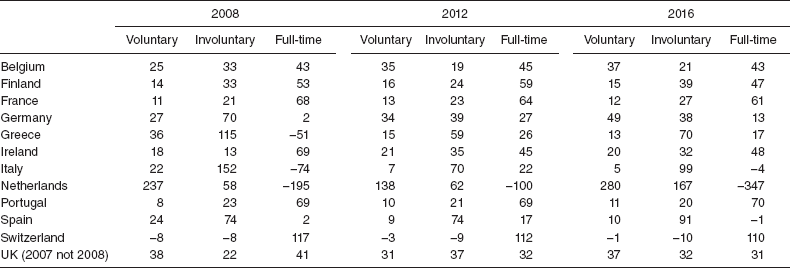

Table 5.2 reports the number of weekly hours of those who say they want fewer hours and those who say they want more hours for thirteen major European countries. (Data for a further thirteen countries and for more years are provided in Bell and Blanchflower, forthcoming.) The numbers of people who want more hours moved sharply upward in the recession. The number who want fewer hours is more stable but does show some increase; that is, the numbers are less negative. They become more negative again in 2016.

The final three columns report the difference between our calculated underemployment rate and the unemployment rate for each of these thirteen countries, for 2007, 2012, and 2016. Fewer and more hours in table 5.2 are added together and divided by average actual hours in the country*year cell to create unemployment equivalents that are added to our estimate of the unemployment rate. In the case of the UK, we use the UKLFS to construct underemployment estimates because the EULFS data file does not contain the numbers who wish to reduce their hours.

Table 5.2. Excess Hours

Note: The difference is the underemployment rate minus the unemployment rate.

Source: Bell and Blanchflower, forthcoming.

These underemployment rates are mostly higher than the equivalent unemployment rates, and especially so in recent years, but in some cases, they are lower. This occurs when, in aggregate, workers wish to reduce their hours rather than increase them. In 2016 the difference was positive everywhere except Switzerland and Lithuania. It makes sense to compare the most recent data with what was occurring well before the onset of recession. In most cases the difference is well above pre-recession levels. Of note is that the difference in the UK was negative pre-recession and positive subsequently. The difference in 2016 is especially high in Portugal.

Germany is of particular note. It experienced a steady decline in the underemployment rate over time from 2004. Switzerland had a negative rate in all years except 1999, showing workers there wanted fewer hours. In almost every other case the rate rose through around 2012 or so and then fell back. This includes Belgium, Denmark, Spain, France, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Cyprus, Estonia, Croatia, Hungary, Iceland, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, and the UK.19 In a couple of other countries, the drop came later; for example, Finland and Romania didn’t see a decline until 2016. Austria and Norway saw steady rises from 2011 and 2012 onward. Luxembourg’s rate reached a peak in 2008. Underemployment rates remain elevated in many countries.

There are obvious biases apparent from table 5.1 in excluding voluntary part-timers and full-timers from any calculation of underemployment in a country. The U7 is a downward-biased estimator of the extent of labor market slack in the period after the Great Recession. The extent of the bias will move over the business cycle and remains uncertain; the United States does not have such data, but it does seem there are consistent time-series patterns across countries. The Eurostat measure is a halfway house and less biased as it uses data from all part-timers but still excludes full-timers. As the recession hit all three groups of workers, involuntary and voluntary part-timers were more likely to say they would like more hours. The table does show also considerable variation across countries, which means it isn’t simple to work out for the United States, which does not have continuous desired hours data. In the UK the three groups each account for about one-third of excess hours in each of the three years. This seems to be a major omission. We will show that the U7 plays a hugely significant role in wage determination in the United States.

Figure 5.2. UK underemployment and unemployment rates. Source: Bell and Blanchflower 2018b.

Figure 5.2 is taken from Bell and Blanchflower 2018b and shows how the UK quarterly underemployment and unemployment rates have moved. In the years before 2008 the UK underemployment rate was below the unemployment rate. In the years after 2008 the underemployment rate rose more than the unemployment rate and recently the gap has closed. Figure 5.3, also for the UK, shows why. It plots the number of hours of those who say they want more hours and the number who say they want fewer at the going wage. The more hours series was broadly flat until recently but was always above the fewer hours series before 2008. That suggests there is still a good deal of underutilized resources in the labor market available to be used up before the UK reaches full employment. It is notable that post-recession in the UK both lines in figure 5.3 have moved upward.

Our index allows for the possibility that not just part-time workers are underemployed. Questions on desired hours are asked of the part-timers who are voluntary and want full-time jobs and full-timers.20 In general full-timers want fewer hours, but both groups of part-timers want more hours. Involuntary part-timers in the UK desire an average of about ten extra hours while voluntary part-timers wanted fewer—around one hour. But there were many more of them. In the years 2001–8 the former group in the UK averaged 2.2 percent of workers versus 4.1 percent in the subsequent period while voluntary part-timers were 18 percent in both periods. It turns out that post-2008 the underemployment rate is more important than the unemployment rate in terms of its impact on wages.

Figure 5.3. UK more hours and fewer hours in millions of hours. Source: Bell and Blanchflower 2018b.

Table 5.3 decomposes the net variation in aggregate desired hours between countries into components from voluntary and involuntary part-timers, and full-timers. It is clear that U7 is a biased estimator of the extent of labor market slack in the period after the Great Recession. The extent of the bias will move over the business cycle and remains uncertain—the United States does not have such data, but it does seem there are consistent time-series patterns across countries. As the recession hit all three groups of workers, involuntary and voluntary part-timers were more likely to say they would like more hours. In the UK, Germany, France, and Ireland, for example, in 2016, involuntary part-time employment accounted for only around a third of excess hours. There is considerable variation in these groups across countries, implying that there is no straightforward relationship that could be exploited to predict the U.S. underemployment rate. This seems a major omission.

Table 5.3. Share of Excess Hours (%)

As an economy moves toward full employment opportunities should increasingly present themselves for underemployed workers who want more hours and overemployed workers who want fewer hours to overcome their hours constraints. Full employment opens up possibilities as more jobs become available. One possibility for those who want more hours is to obtain a second job. A further possibility would be for employees to switch to self-employment, where they could choose their own hours. Self-employment could be a secondary or primary job. This should be especially apparent as the economy moves closer to full employment. There is no evidence in the data so far to support such a claim in the United States or the UK on either front in the recent period when the unemployment rate dropped below 5 percent to 4 percent and lower.

There is no evidence of any rise in either the United States or the UK in multiple job holding as the unemployment rate dropped below 5 percent. In the UK in April 2008 there were 1.12 million workers with more than one job or 3.8 percent of total employment. In October 2018 there were also 1.12 million at a rate of 3.42 percent. In the United States there were 7.6 million multiple job holders in January 2008 (5.2% of jobs) versus 7.8 million in January 2019 (4.9%). Hirsch, Husain, and Winters (2016) find no relationship in the United States between multiple job holding and unemployment. Lalé (2015) finds similarly. Pouliakis (2017) finds that the multiple job holding rate in the EU28 has remained roughly constant over the last fifteen years.

Just as there is no evidence of a rise in multiple job holding in the United States or the UK as the unemployment rate has fallen below 5 percent, there is also no evidence of a significant rise in self-employment in either country as that happened. The self-employment rate in the UK, measured as self-employment as a percent of total employment, rose from 13.1 percent in April 2008 to 15.1 percent in September 2016 when the unemployment rate was last 5 percent. In the period since then through August 2018 when the unemployment rate dropped to 4.0 percent, the self-employment rate fell back to 14.9 percent in October 2018.

In the United States the seasonally adjusted number of unincorporated self-employed was 10.2 million in January 2008 and 9.6 million in January 2019. The unadjusted number of incorporated self-employed, which is the only number the BLS reports, rose from 5.8 million to 6.0 million over the same period. The unemployment rate was last 5 percent in September 2016. The self-employment rate in the United States, obtained by adding the incorporated and unincorporated numbers together, fell from 10.8 percent in January 2008 to 10 percent in September 2016 when the unemployment rate was last 5 percent. The unemployment rate dropped further to 4.0 percent in January 2019, up from 3.7 percent in November 2018, and the self-employment rate remained unchanged at 10 percent.

If the United States or the UK were anywhere close to full employment I would have expected to see evidence from both self-employment and multiple job holding that the underemployed were starting to move their actual hours closer to their desired hours. None is apparent in the data.

Wage Growth and the Lack of It, Explained

This section establishes some key stylized facts for a range of labor markets before and after the Great Recession. Our first piece of evidence concerns low wage growth internationally.

A major part of this lack of wage response post-recession is because of globalization. This includes the fear that migrants may come and take away jobs. It also includes the possibility that a firm will move production abroad or subcontract parts of its work abroad. The weakening of labor unions, which have seen their membership decline around the world, means workers have little bargaining power. Some of the story for flat wage growth also turns out to be because of underemployment, which continues to remain elevated. In some ways the very existence of underemployment arises because of the weakness of worker bargaining power. Underemployment is less prevalent in the union than in the non-union sector.

Important recent work by Hong et al. (2018) from the IMF across thirty countries has shown that the involuntary part-time rate (IPTR)—expressed as a percent of total employment—significantly lowers wage growth.21 They find that, on average, a 1-percentage-point increase in the involuntary part-time employment share is associated with a 0.3-percentage-point decline in nominal wage growth.

Importantly Hong et al. find that the effect is more pronounced in countries where the unemployment rate is below pre–Great Recession averages—the Czech Republic, Germany, Japan, Israel, the Slovak Republic, the UK, and the United States. Within this group of countries, a 1-percentage-point increase in the involuntary part-time employment share is associated with a 0.7-percentage-point decline in wage growth. The estimated effect is only 0.2 percentage point for countries with unemployment appreciably above the pre—Great Recession averages. The authors conclude that “involuntary part-time employment appears to have weakened wage growth even in economies where headline unemployment rates are now at, or below, their averages in the years leading up to the recession” (2018, 2).

Hong et al. kindly provided their data to David Bell and me; we then mapped onto the data our underemployment rates for nineteen of the countries.22 We found that for the whole period covering both pre- and postrecession, both the unemployment rate and the underemployment rate significantly lower wage growth. Post-2008 only the underemployment rate lowers pay growth while the unemployment rate has no effect. David and I find similar results below with the IPTR for the United States.

David Bell and I (2018b) created a balanced panel of twenty regions by sixty-two quarters for the UK from 2002 Q2 to 2017 Q3 using data from the LFS. We found the unemployment rate had no impact on pay over this period. In contrast we found that our “under hours” variable significantly lowered wages. On top of that we found some evidence that “over hours” raised pay; workers who wanted fewer hours received a compensating differential. Underemployment lowers wages and overemployment raises them, while unemployment does not have an impact in the UK.

In a subsequent work David Bell and I (forthcoming) examined hourly and weekly wages using state-level data from the BLS matched by state and year to data from the Merged Outgoing Rotation Group files of the CPS for 1980–2017. We take the microdata in each year and collapse it to the state*year cell to calculate wages as well as personal characteristics including schooling, age, race, and gender. The personal controls are measured across all individuals while the wage data are calculated for employees only, and part-time for economic reasons variables are calculated for all workers. We mapped that onto state-level data from the BLS on the unemployment rate (U3) as well as data on U4 through U6, which are alternative measures of labor market slack, from 2003 through 2017.23 Bell and I found that the unemployment rate lowered wage growth in the period 1980–2007, consistent with the earlier findings for the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s in Blanchflower and Oswald 1994.

We then restricted the period to the years since the onset of the Great Recession, which the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee categorized as starting in December 2007. There is no wage curve in hourly wage*unemployment space in the post–Great Recession period. We then added the part-time for economic reasons, defined as a proportion of total employment, which has a significant negative coefficient with or without the presence of the unemployment rate. So, there is a wage curve in wage*underemployment space. We also included the change in the home-ownership rate as a control, which was negative in every year from 2005 but became positive in 2017. The variable enters significantly negative: a falling homeownership rate lowered wage pressure in the period since 2008.

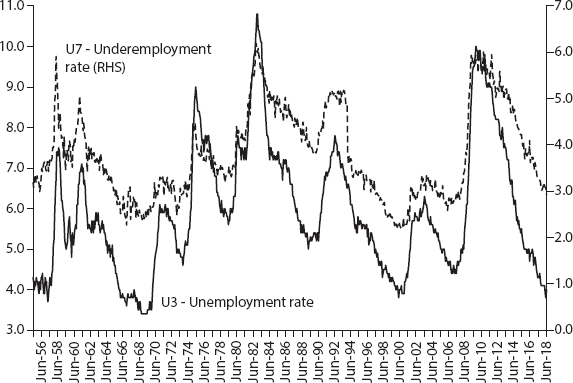

Figure 5.4. U.S. unemployment and underemployment rates, June 1955^June 2018. RHS = right-hand side. Source: BLS.

Figure 5.4 plots the U.S. unemployment rate (U3) and the underemployment rate (U7) since May 1955, which shows that the latter remains above its pre-recession low of 2.2 percent, last observed in October 2000. An unemployment rate of 3.9 percent was last seen in December 2000. The low of the unemployment rate series was 3.4 percent, which was last seen in May 1969.

This new U7 variable significantly lowers wage growth while the unemployment rate (U3) has no effect. We also created two new variables we call U8 and U9, which identify the discouraged and marginally attached worker rates, expressed as a percentage of the civilian labor force. To be clear then, as constructed, U7a + U8 + U9 = U6, where here the denominator of U7a is the labor force, not employment. U8 and U9 are both insignificant. In terms of wage growth, the U7 variable is driving all the action in the U6 variable and in the years since 2008, U3, U8, and U9 are irrelevant. Underemployment matters these days as a measure of labor market slack in wage determination while unemployment does not.24

In the later period the significant and negative U7 variable allows us to calculate the long-run underemployment elasticity, which is -.03. So, there is still a well-defined wage curve in wage underemployment space. The change in the homeownership rate is once again significantly negative. Wage responsiveness post-recession to a change in labor market slack has fallen. We found similar results for the UK (Bell and Blanchflower 2018b).

Underemployment Has Replaced Unemployment as the Main Measure of Labor Market Slack

In the post-recession period underemployment has replaced unemployment as the main indicator of labor market slack. Notably, underemployment has not returned to its pre-recession level in many countries whereas unemployment has. In the past, at the low levels of the unemployment rate existing in countries like the UK, Germany, and the United States, there was a pay norm growth rate of 4 percent in the years before the Great Recession and 2 percent or a little higher subsequently. Wages grew by 4 percent and more a year before the Great Recession and 3 percent and less after it: it’s as simple as that. The reason is that in 2018 underemployment is pushing down on wages while the unemployment rate contains little or no information at such low levels in either the UK or the United States. At the very least the unemployment rate is having much less impact than it did before the Great Recession.

David Bell and I in a series of papers have constructed an underemployment index that is preferable to using the data on part-timers who can’t get full-time jobs. We found evidence across European countries that voluntary part-timers also report wanting more hours and Eurostat now uses this in their definition of underemployment. In contrast, if full-timers say they want to change their hours it is usually to decrease them. During the recession the number of additional hours part-time workers wanted, whether voluntary or involuntary, increased sharply. There was also a fall in the number of hours full-timers wanted their work weeks to be reduced by. In the recovery, just as the number of involuntary part-timers fell, so did our index. The extent of the bias in only having the number of PTFER as in the United States remains unclear. Trends in our series and the involuntary part-time rate, whether expressed as a percent of total employment or the labor force, seem to vary by country.

We find evidence (Bell and Blanchflower, forthcoming) that in the years after the Great Recession underemployment predicts what is happening to wage growth, whereas unemployment does not. Existing levels of underemployment are predictive of low wage growth because they do not suggest economies are at full employment. The low levels of the unemployment rate suggest much higher levels of wage growth than are being observed and appear to be giving policymakers a false signal. Underemployment matters; unemployment does not.

Declines in the homeownership rate appear to have lowered the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) in the United States and likely have done the same in other countries such as the UK that have also seen sharp declines in homeownership rates. Oswald and I (2013) estimate that implies that a 10-percentage-point rise in the homeownership rate in the United States will equate to an extra 1.5 percentage points in the unemployment rate. Hence a 5- to 6-point move downward in the home-ownership rate, which is what we have seen, implies a fall of 0.8 percentage points in the natural rate of unemployment, or the NAIRU. A lower NAIRU implies less wage growth at a given unemployment or underemployment rate. The wage curve in the years since the Great Recession in the United States exists in wage underemployment space.

Even though the unemployment rate is at historic lows in many countries, this does not suggest that these countries’ labor markets are anywhere close to full employment. Full employment likely does not mean excessively high underemployment rates where workers are willing to work more hours at the going wage.

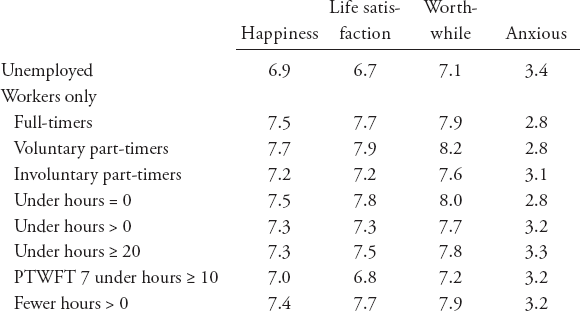

David Bell and I also found in a further paper (2018c) that workers do not seem to like underemployment. In part, as noted above, the reason is likely to come from their irregular work schedules and lower pay. There is some evidence from the UK from well-being surveys that supports that contention. The ONS in the UK collects data on happiness, life satisfaction, anxiety, and whether life is worthwhile as a supplement to the Labor Force Survey. Below I report well-being rates for various groups of workers: these are all scored from 0 (not at all happy) to 10 (completely happy) and the data cover the years 2013–17.

For each of these measures involuntary part-timers are less content than voluntary part-timers or full-timers. However, they do not have the low levels of well-being of the unemployed. The underemployed do not want to be underemployed. The overemployed are anxious.

Bell and I (2018c) found remarkable evidence that depression in the UK, using the Labour Force Surveys, has risen since 2010, when it was 1.6 percent, to 3.6 percent in 2018. The rise was especially apparent among the underemployed, whose incidence of depression rose from 1.5 percent in 2010 to 4.8 percent in 2018. This was a bigger proportionate rise than experienced by the unemployed (2.9 to 8 percent).

It would make sense for the BLS to include a question on workers’ desired hours in its Current Population Survey given the importance of the involuntary part-time variable in explaining U.S. wage growth. It remains uncertain how much additional information would be obtained from being able to construct our measure, because in the analysis we performed the results from using our index are broadly similar to those using an involuntary part-time measure in the UK. The extent of any bias is uncertain, though, given the rather different results by country in terms of the share of underemployment accounted for by the involuntary part-timers.

In the post–Great Recession years, measures of underemployment replace unemployment as the primary indicators of labor market slack in many countries and help provide a more convincing explanation of wage growth. The fact that underemployment has not returned to pre-recession levels is a big part of the benign wage-growth story.