CHAPTER 7

Sniffing the Air and Spotting the Great Recession

Today, the economist who wanders into a village to get a deeper sense of what the data reveals is a rare creature.

—JOHN RAPLEY, Twilight of the Money Gods

Economics isn’t magic. My PhD supervisor, Bernard Corry, taught me to try to understand the low-side risk of any policy prescription, by which I mean always worry about the consequences if you are wrong. I remember him telling me on numerous occasions that I should be concerned about the welfare of the man or woman commuting on the train or bus or, as he put it, worry about the welfare of the “man on the Clapham omnibus.”1

In part this was to ensure that economists did no harm, and also because Bernard understood that this bus passenger was paying his salary. Interestingly, Clapham is now a pretty prosperous part of London. Bernard always encouraged me to look at the data carefully and to sniff the air. To adopt a more “investigative” approach, if you like: to put the data before the theory. People know what’s going on: just ask them.

I first coined the phrase “the economics of walking about” in a lecture I gave on May 30, 2007, at Queen Mary College in honor of Bernard.2 He encouraged me to look at the data carefully and to look for patterns in the data. This is in direct contrast to much of economics that apparently believes the real world is a special case and uninteresting. In my view economics is not just about understanding mathematics or elegant theoretical models. Statistics and statistical analysis are not the be-all and end-all of course. What matters is the interpretation and the questions that are asked.

The timing was pretty good. The economics of walking about (EWA) gave an early indication that a major recession was coming in 2007 and 2008 in advanced countries. It is the articulated vision of experience. The people know what is happening around them. Taking seriously what firms and individuals were saying gave an early indication that something horrible was coming.

The Economics of Walking About

An early example of EWA was one of the first papers Andrew Oswald and I published together (1988) that reported on what personnel managers said when they were asked what factors influenced the level of pay in the most recent pay settlement. We reported results separately for blue- and white-collar workers. In the case of blue-collar workers, the influences were different between union and non-union sectors. Non-union sector respondents were much more likely to say merit payments were important.

I recall economists at the time being highly critical of using this sort of data. One commentator at a seminar when I first presented the paper asked me, “What would personnel managers know about the setting of pay?” My response was, “Everything,” which seemed to take him by surprise. Despite the opposition of economists, the working paper was apparently one of the Centre for Labour Economics’ most requested ever. Those who did the economics of walking about liked it. Most economists hated it. I recall the seminar audience really didn’t like the paper. I still really like it, mostly for its simplicity. Pay, the paper showed, is set by an intricate blend of insider and outsider forces and I still believe that.

Ins and outs, as Bob Solow pointed out, are “as old as the hills” and were well known by the old generation of labor economists like Sumner Slichter, John Dunlop in the United States, Sidney and Beatrice Webb in the UK, and more recently Sir George Bain and Willie Brown. We did a couple of econometric papers that confirmed what the personnel managers said.3

During the 1970s the UK unemployment rate rose inexorably. The overall unemployment rate, though, remained below 6 percent to the end of the 1970s. It hit 6 percent in March 1980 and by the summer of 1981 had reached 10 percent, eventually reaching 11.9 percent in the spring of 1984. The unemployment rate didn’t get back below 6 percent until May 1999 under Tony Blair’s Labour government, having been in double digits between September 1992 and January 1994.

My sense at the time was that as the overall unemployment rate started to rise, the situation facing young people was worsening rapidly. I had been teaching in schools and colleges from 1974 through 1979 and had the sense that the job opportunities were diminishing. This was my first time doing the economics of walking about. I didn’t buy that youth unemployment by 1982 was not a growing problem. I wrote my master’s thesis at University College, Cardiff, in Wales on youth unemployment. Layard (1982) had argued that the UK didn’t have a youth labor market problem and sought to explain why youth unemployment in the UK was so low, relative to U.S. rates. He reported data from 1959 through 1977 for the two countries. He argued the difference came down to higher U.S. incomes and the fact that income maintenance in the United States was lower. Plus, he claimed, “apprenticeship programs provided a strong incentive for British youths to be employed” (1982, 500). I didn’t buy it.

My conclusion from interacting with young people as a teacher and lecturer through the 1970s was that by 1980 youth unemployment had become a big problem in the UK. Increasingly my students, who were based in the South of England in and around London, were struggling to find jobs. Some of my former students wrote and told me they were losing their jobs in the City of London. Jobs for young people were becoming hard to find.

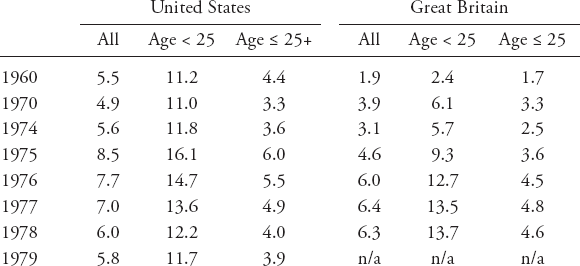

A paper from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in September 1981 by Constance Sorrentino suggested that by the start of the 1980s there was change in the air. Sorrentino had two more years of data than Layard, with data adjusted to U.S. concepts, and showed that UK unemployment rates for those under 25, as Layard found, were everywhere below the U.S. rate from 1960.4 But by 1977, which was Layard’s stopping point, the situation had begun to reverse itself, at the same time as the UK aggregate unemployment rate plotted in figure 1.1 overtook the U.S. rate. Layard didn’t see this coming. The age-specific unemployment rates are set out below.

We do not have good data for the period 1980–82, but we do have comparable monthly data ever since January 1983 for both the United States and the UK for those under 25. By January 1983 youth unemployment rates, for those 16–24 in the UK, reached 20 percent versus 18.5 percent in the United States. Over subsequent years the monthly youth unemployment rate for those under 25 in the UK was mostly above the U.S. rate. Things can change quickly in the labor market. Despite the fact that the overall unemployment rate in the United States reached 10 percent versus 8.5 percent in the UK, youth unemployment rates in the UK during the Great Recession were always higher than in the United States, peaking at 22.3 percent in October 2011 versus 19.7 percent in the United States in May 2010.

The economics of walking about is fundamental to this book. There are many ways of doing so. Some commentators even track the color of Mario Draghi’s tie. It is usually blue when he announces a policy change. There is even a “lipstick index,” which is a term coined by Leonard Lauder, chairman of the board of Estée Lauder, who noted an increase in sales of cosmetics in the early 2000s recession. Women buy lipstick in tough times when they can’t afford to buy clothes. In the 2010s there was talk of a nail polish index. Economic downturns have a wide range of effects on medicine; in recessions the volume of both elective and non-elective procedures decreases. Interestingly, however, vasectomies increase during recessions.5 According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, in 2008 fewer cosmetic surgical procedures were performed than were in 2007: breast augmentations were down 12 percent; tummy tucks were down 18 percent; liposuction was down 19 percent; and facelifts were down 5 percent.6

Bloomberg’s Richard Yamarone, whom I knew and fished with on occasion and who sadly died recently, was famous for noting that an important indicator of how the economy was doing was the previous quarter’s sales of women’s dresses (2012, 2017). His argument was that women tend to determine most household—and therefore consumer—spending and that their dress purchases are uniquely dictated by themselves. Yamarone explained that these resulting “luxury” purchases tell us a lot about discretionary income in the American home. Other indicators include the amount that Americans are spending on dining out, jewelry and watches, and casino gambling.

Yamarone argued in his Economic Indicator Handbook that his dress sales index shouldn’t be confused with the hemline index, a theory propounded by George Taylor in 1926. The idea is that hemlines on women’s dresses rise along with stock prices. In good economies, we get such results as miniskirts as seen in the 1920s and the 1960s. In poor economic times, as shown by the 1929 Wall Street Crash, hems can drop almost overnight. Van Baardwijk and Franses (2010) collected monthly data on the hemline for 1921–2009 and evaluated these against the NBER chronology of the economic cycle. Their main finding is that “the economic cycle leads the hemline with about a three-year lag.” We should probably take this research with a major pinch of salt, though, given that ten years in I see little evidence of ankle-length skirts.

As Tamar Lewin reported in a column in the New York Times in 2008, Leo Shapiro, chief executive of SAGE, a Chicago-based consulting firm, has suggested that buying patterns can be predicted in economic downturns: “During a recession, laxatives go up, because people are under tremendous stress, and holding themselves back. During a boom, deodorant sales go up, because people are out dancing around. When people have less money, they buy more of the things that have less water in them, things that are not so perishable. Instead of lettuce and steak and fruit, it’s rice and beans and grain and pasta. Except this time the price of pasta’s so high that it’s beans and rice.”7

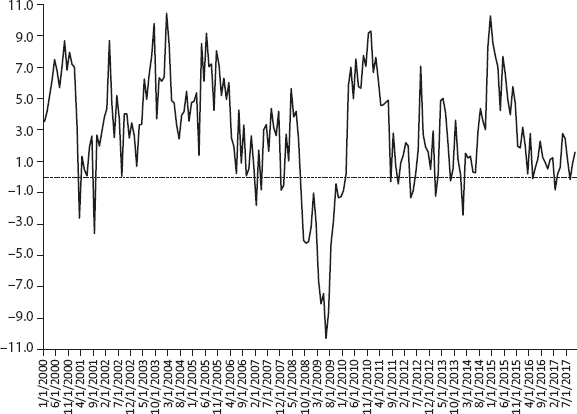

More seriously, Yamarone suggests that women don’t make cuts to the kids’ dance classes, soccer, baseball, or piano lessons. They will, he suggests, reduce expenditures of a self-purchase before reducing expenditures on their family and there is no greater self-purchase than a dress. Yamarone’s famous chart is the annual percentage year-on-year change in the value of sales of women’s and girls’ clothes shown in figure 7.1.8 It plunged in 2008 and has fallen steadily since the end of 2014.

Figure 7.1. Yamarone’s year on year % change in the U.S. sales of women’s and girls’ clothes, 2000–2017.

Two stories from the UK from the fall of 2016 are illustrative of what can be learned from the economics of walking about. The Washington Post reported on an already gathering economic storm for Britain. It reported that Brexit was already spooking some British companies, including a 122-year-old British firm based in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, called Smiffys. On their website (www.smiffy.com) they report they have been in the business of fancy dress since 1894, becoming a global organization with offices and showrooms worldwide: “As the leading fancy dress, Halloween and Carnival manufacturing company in the UK, we distribute nearly 5,000 products to over 5,000 stockists around the world, with over 26 million items shipped every year.” Their mission, they say, is “to be the best, most liked, trusted and respected company in our industry.” The Washington Post reported that, due to Brexit uncertainty, Smiffys are leaving the UK to head to Amsterdam, the capital city of the Netherlands, and inside the EU. Elliott Pecket, the company’s director, argued, “One word sums up the issue: uncertainty. Any business needs as much certainty as it can get around the cost of goods or the markets you can trade in. But right now, you don’t know where you are from one day to the next.”9

Smiffys was the first of many firms that are likely to quit the UK if there is a disorderly Brexit. In many ways, the economics of walking about is nothing more than market intelligence. The question is, how much slowing in the UK economy will result from Brexit, especially as the UK government doesn’t seem to have a plan and is tied up in litigation? It will be crucial to watch carefully what Keynes called “animal spirits” and how economic sentiment changes. I suspect there may be more Smiffys.

Rivington Biscuits, the maker of Pink Panther wafers, went into administration in December 2016, blaming the fall in the value of the pound following the Brexit vote.10 The company, a key employer in Wigan, which voted to leave the EU by nearly 64 percent, said it would cut 99 of its 123 staff to fill remaining orders. Rivington Biscuits’ financial position worsened in the wake of the June referendum, as the slump in the value of the pound pushed up the cost of ingredients used to make its biscuits.

Up to 1,000 bankers working for JP Morgan in the City of London are to be relocated to Dublin, Frankfurt, and Luxembourg. Standard Chartered told their shareholders at its annual meeting in London in 2017 it was talking with regulators in Frankfurt about setting up a new subsidiary in Germany. Deutsche Bank warned in 2017 that up to 4,000 UK jobs could be moved to Frankfurt and other locations in the EU as a result of Brexit.11 Barclays has chosen Dublin as its post-Brexit hub. Goldman was one of the first financial institutions to announce it was moving staff away from the UK. In 2017 Goldman decided to close some of its hedge fund operations in London and move the staff to New York. The world’s biggest specialist insurance market, Lloyds, announced it would be seeking a new Brussels-based subsidiary the day after UK prime minister Theresa May invoked Article 50, the official EU exit clause.12

In June 2018 aerospace giant Airbus said that the “severe negative consequences” of withdrawal from the EU could force it to leave Britain.13 Airbus said it might ditch plans to build aircraft wings in British factories over concerns that EU regulations will no longer apply as of March 2019 and uncertainty over customs procedures, instead opting to transfer production to North America, China, or elsewhere in the EU. Airbus directly employs 14,000 people at 25 sites in Britain and supports more than 100,000 jobs in the wider supply chain.14 At Broughton in north Wales, the Airbus plant has 6,000 staff, Aditya Chakrabortty notes, “in an area that 40 years ago was pretty much stripped of its steel industry. If it loses that giant factory, the local economy will be back on the floor for decades. Some will doubtless point out the irony of the leave voters of north Wales now paying for their votes with their jobs.”15 Wales voted for Brexit.

Lloyds of London says the government’s plan for relations with the EU after Brexit will speed up the departure of firms from the UK. On July 14, 2018, Inga Beal, its CEO, said the government’s white paper on Brexit would see the three-hundred-year-old insurance market go “full speed ahead” to set up its subsidiary in Brussels—and spur others on as well. Lloyds (not in) London. On July 4, 2018, Britain’s biggest car maker, Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), warned that a hard Brexit would cost £1.2 billion a year in trade tariffs and make it unprofitable to remain in the UK.16 Ralf Speth, JLR chief executive, said, “We have to decide whether we bring additional vehicles, and electric vehicles with new technology with batteries and motors into the UK.” He added, “We have other options. If I do it here and Brexit goes in the wrong direction, then what is going to happen to the company? If I’m forced to go out because we don’t have the right deal, then we have to close plants here in the UK and it will be very, very sad.”17 Votes have consequences.

CNN Money has a “Brexit Jobs Tracker” that identifies companies moving jobs or investment from the UK because of Brexit.18 As of November 12, 2018, there were twenty-five on the list. After being praised by Boris Johnson for moving to London five years earlier, Japanese pharmaceutical firm Shionogi announced in March 2019 that it was moving its headquarters to Amsterdam. According to the Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency, in January 2019 more than 250 companies were in discussions about Brexit-driven relocations.19

The Literature on Walking About and Not Sniffing the Wine

Orley Ashenfelter from Princeton University is another believer. He is famous for his controversial but correct work on modeling the quality of red Bordeaux using data (2008, 2017). He is no slouch; he was editor of the American Economic Review, the main journal of the American Economic Association and the most prestigious journal in economics. He looks at the location of the vineyard and the weather and can predict the quality of the wine via a simple equation. Facing south at an angle of forty-five degrees is important, as there are vineyard fixed effects; some locations are just better than others. He finds no evidence for any separate effect from the winemaker. His prediction doesn’t change over time. Orley predicted the 1989 Bordeaux would be “the wine of the century” and claimed the 1990 vintage was going to be even better. His method has the great benefit that you don’t have to open bottles of unripe wine to see how the wine is maturing. You don’t have to sniff undrinkable wine with Orley’s method so there is more wine to drink. You can save it for a later day. Brilliant.

Britain’s Wine magazine said, “The formula’s self-evident silliness invite[s] disrespect.” But they would say that, wouldn’t they, because if Ashenfelter is right, which I suspect he is, wine critics are largely out of a job. In his case, he doesn’t have to sniff the wine; he just looks at how much sun and rain there is and when.20 Ashenfelter writes, “There is now virtually unanimous agreement that 1989 and 1990 are two of the outstanding vintages of the last 50 years” (2008, F181). He also suggests the 2000 and 2003 vintages are in a league similar to the outstanding vintages of 1989 and 1990. The weather was also exceptional in those years. A great example of the economics of walking about and up and down those steep vineyards.

In a new paper (2017) Ashenfelter argues that if the relation between weather and grape quality is known for each grape type in existing growing areas, then it is possible to predict the quality of grapes that would be produced in other locations, or in the same location with a changed climate. This permits the optimization of grape type selection for a location and also provides an indication of the value that a particular planting should produce. The relation of grape quality to the weather is reported by Ashenfelter for several well-known viticultural areas, including Burgundy, Bordeaux, Rioja, and the Piedmont.

Ashenfelter applied this method to a new vineyard area, Znojmo, in the Moravian province of the Czech Republic following the demise of communism. His main finding is that the highest-quality vintage in Znojmo would have been about 83 percent of the quality of a top Burgundy vintage. On the other hand, the worst Znojmo vintage would have been twice the quality of the worst Burgundian vintage in the period from 1979 to 1992. On average, the typical Znojmo vintage would have been about 75 percent of the quality of the typical Burgundian vintage. Ashenfelter concludes that there is considerable potential for producing high-quality pinot noir wines in the Czech Republic. Nice.

Ashenfelter also has written about the art market, the value of life, hospital mergers, and McWages, to name but a few other data-driven projects. He has published on how to not lie with statistics, as well as on lawyers as agents of the devil in a Prisoner Dilemma game and pendulum arbitration. He also examined the behavior of identical twins using data from the Twins Days Festival at Twinsburg, Ohio. Looking at the data is an honorable estate. Others walk about too. Phew.

Another study that looks at the data is David Card’s famous article on the effect of the Mariel Boatlift of 1980 on the Miami labor market (1990). The Mariel immigrants increased the Miami labor force by 7 percent, and the percentage increase in labor supply to less-skilled occupations and industries was even greater because most of the immigrants were relatively unskilled. Nevertheless, the Mariel influx appears to have had virtually no effect on the wages or unemployment rates of less-skilled workers, even among Cubans who had immigrated earlier. The author suggests that the ability of Miami’s labor market to rapidly absorb the Mariel immigrants was largely owing to its adjustment to other large waves of immigrants in the two decades before the Mariel Boatlift.

Still another fine example of working out what was happening in the real world is the 2004 case study by Alan Krueger and Alexandre Mas of the effect of labor relations on product quality. This was economic detective work. They examined whether a long, contentious strike and the hiring of permanent replacement workers by Bridgestone/Firestone in the mid-1990s contributed to the production of an excess number of defective tires. Using several independent data sources, the authors found that labor strife in the Decatur, Illinois, plant was closely correlated with lower product quality. They found significantly higher failure rates for tires produced in Decatur during the labor dispute than before or after the dispute, or than at other plants.

Monthly data suggest that the production of defective tires was particularly high around the time wage concessions were demanded by Firestone in early 1994 and when large numbers of replacement workers and permanent workers worked side by side in late 1995 and early 1996. The stock market valuation of Bridgestone/Firestone fell from $16.7 billion to $7.5 billion in the four months after the recall of tires was announced and the top management of Bridgestone/Firestone had been replaced. The company also closed the Decatur plant in December 2001.

In a path-breaking book titled Myth and Measurement (1995), David Card and Alan Krueger examined data from a series of recent episodes, including the 1992 increase in New Jersey’s minimum wage, the 1988 rise in California’s minimum wage, and the 1990–91 increases in the federal minimum wage.21 They found evidence showing that increases in the minimum wage led to increases in pay but no loss in jobs. Increases in the minimum wage led to productivity growth as tenure rates rose and quit rates fell.

A big question in economics is why wages and salaries don’t fall during recessions. Truman Bewley (2002) explored this puzzle by interviewing over three hundred business executives and labor leaders, as well as professional recruiters and advisors to the unemployed, during the recession of the early 1990s. He found that the executives were averse to cutting wages of either current employees or new hires, even during the economic downturn when demand for their products fell sharply. They believed that cutting wages would hurt morale, which they felt was critical in gaining the cooperation of their employees and in convincing them to internalize the managers’ objectives for the company.

Golf handicap also seems to matter for CEOs.22 A study based on publicly available data from the United States for the years 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2006 examined the relationship between golf handicaps of CEOs and corporate performance and CEO compensation. The study found that golfers earn more than non-golfers and CEO pay increases with golfing ability. Despite that, the authors find that there is no relation between golf handicap and corporate performance.

A London limo driver in January 2017 told me the problem in Britain, and the reason there was a vote for Brexit, was that ordinary people had no hope. He told me he had to balance the need to spend time with his kids (ages 6 and 13) with the need to drive many more hours than he had in the past to make enough money to live. He told me it was tough for him to have lost hope as he had always been an optimist. Another limo driver in Southampton told me he had voted for Brexit as a protest vote, not expecting it would win. Once Brexit won he immediately regretted his vote.

Applying EWA to the Crisis: London Cabbies, Delivery Trucks, and Jingle Mail

There are many ways to sniff the air out and about. A taxi driver in early January 2008 was driving me down Oxford Street. It is full of clothes stores and big department stores like Selfridges and Debenhams and John Lewis, and in the January sales it should have been a frenzy of activity. My cabbie pointed out something unusual about the shoppers that year: they had no bags and were only window shopping. People didn’t have any money to spend.

I spoke to other London taxi drivers during the first half of 2008. London cabbies, I find, are always a good source of information on what is happening in London. At first, they were big supporters of the new mayor of London, Boris Johnson, but then they quickly turned against him. A number told me that they were having to work more hours to make their money every week. Some of them told me that they were fortunate because they could increase their hours but many of their friends and family weren’t as lucky. Hours of work were falling, and people were being laid off.

The cabbie’s hunch likely was correct, but there were other possibilities to explain the decreased presence of shopping bags. One possibility was that people were less likely to be shopping on the high streets, where rents tend to be high, leading to higher prices, and more likely to be browsing there but buying in large stores further out that offered lower prices due to lower rents and greater economies of scale. Another possibility is that people were moving away from purchasing at brick-and-mortar stores and increasingly buying online, with the convenience of having items delivered to one’s home. From the simple observation that people were not carrying shopping bags, multiple possible explanations exist. The taxi driver offered a telling anecdote, but its meaning was open to interpretation. It turns out the economy was slowing and the published economic data hadn’t caught up.

A couple of weeks after the cab driver spoke to me an owner of a company in the UK that operated a tire service called me. This firm had taken over a fleet and serviced all their tire needs. If tires needed replacing or had a puncture out on the road, the firm would sort it. As part of that every delivery truck they serviced had tachometers in them to record how many miles were being driven. He called to tell me he had noticed that the mileage on the delivery trucks he serviced was way down.

In the United States a new phenomenon emerged (which economists failed to spot) around 2007 as the housing market started to slow and subprime mortgages began to fail: “jingle mail.” By early 2007 a growing number of mortgage holders were failing to make their monthly payments, especially among subprimes, which induced a wave of selling. As a result, prices fell and continued to do so. John Rapley explained it well: “So prices fell further, and more borrowers missed payments—or simply walked away from their homes, leaving their keys in the bank’s night deposit boxes. Bankers soon began to dread this ‘jingle mail’” (2017, 362).

Economists, including those in academia, Wall Street, and Canary Wharf, as well as in central banks around the world, of course had no clue this was happening. But it isn’t as if this hadn’t happened before. This term was first used to describe the surprise mailings that mortgage lenders received following the savings and loan debacle of 1990–91.

A 2010 paper from the Richmond Fed found that the probability of default on a mortgage loan was 32 percent higher at the mean value of the default option at the time of default in nonrecourse states than in recourse states.23 There are eleven nonrecourse states: Alaska, Arizona, California, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin. In these eleven states, banks’ recourse in collecting on residential “purchase” mortgages after default is limited to the value of the collateral (the home). If the debt is larger than the value of the home, usually determined by proceeds from the foreclosure sale, the lender is generally barred from trying to collect the remainder of the debt from the borrower. So, mortgage holders who were underwater walked away especially in these states.

As Paul Krugman noted,

Economists were also under-informed about the surge in housing prices that we now know represented a huge bubble, whose bursting was at the heart of the Great Recession. In this case, rising home prices were an unmistakable story. But most economists who looked at these prices focused on broad aggregates—say, national average home prices in the United States. And these aggregates, while up substantially, were still in a range that could seemingly be rationalized by appealing to factors like low interest rates. The trouble, it turned out, was that these aggregates masked the reality, because they averaged home prices in locations with elastic housing supply (say, Houston or Atlanta) with those in which supply was inelastic (Florida—or Spain); looking at the latter clearly showed increases that could not be easily rationalized.” (2018, 158)

Duh!

A further method of sniffing the air is simply to “eyeball the data.” It has been said that the plural of anecdote is data and that statistics is simply the collection of anecdotes. The benefit of statistics is that it allows multiple possible explanations to be tested against the evidence, or the collection of anecdotes. These data generally involve sampling firms or individuals, asking their opinions and summing them together into some sort of score. Examples are surveys of firms as conducted, for example, by Markit, which talks to purchasing managers to produce Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs) for many countries and sectors. The Bank of England’s agents talk to contacts and produce scores of what firms think about all sorts of variables including employment, investment, prices, and turnover.

Consumers are surveyed about their views on the economy. The most well-known of these individual-level surveys is the consumer confidence index. In the United States, the two most famous are those of the Conference Board and the University of Michigan. In the UK, the EU consumer confidence index is the most well-known, conducted monthly in all twenty-eight member countries of the EU by the European Commission. These are not the sort of data that academic economists look at. They spend their academic lives looking at the past, not the present.

The statistics show that both the taxi driver and the tire-service owner were on to something. What they noticed was that consumer confidence was down and people were spending less because they were worried about the future. Consumer confidence, as it turns out, is something that can be measured. What was evident by January 2008, and probably even before that, was that consumer confidence was headed sharply down.

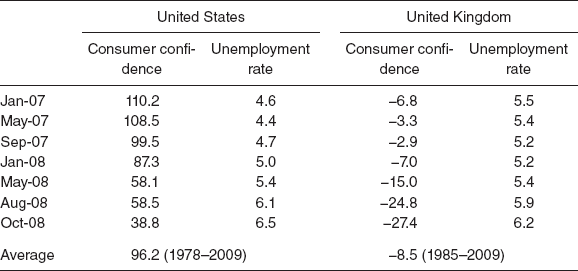

Look at table 7.1, which plots what Keynes called “animal spirits.” It plots consumer confidence indices—which show how confident consumers are about the economy—for the United States and the UK along with the respective unemployment rate. For the United States, it is from the Conference Board’s measure and for the UK it is from the EU Commission. I do need to do some housekeeping with these qualitative surveys. Sometimes the index is reported as a number, as with the Conference Board, which has 1985 = 100. In other instances, which include the EU Commission survey, they are reported as a balance. So, if the respondent is asked if something was worse (20%), the same (25%), or better (55%), the balance is calculated as better minus worse = +35. It is useful to compare to the long-run survey average. To put it simply, more is better, less is worse.

Table 7.1. Animal Spirits: Consumer Confidence and Unemployment, United States and United Kingdom

Source: Blanchflower 2008.

It is clear that the two data series moved down sharply together and appear to have done so before the unemployment rate rose. In the United States, the high point was 111.9 in July 2007 and the unemployment rate started picking up in December 2007. These are the data the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee determined showed the start of the Great Recession. It was pretty obvious by spring 2008 consumer confidence had collapsed and the unemployment rate was climbing in both countries. Animal spirits were plunging but nobody much noticed.

In the UK case, the consumer confidence index appears to have started falling sharply from the beginning of 2008 and was falling fast by April 2008, which, based on the GDP data, was the start of the UK recession. The unemployment rate started to rise around July 2008. What happened in the United States spread to the UK within a very few months and from there to the rest of Europe and beyond.

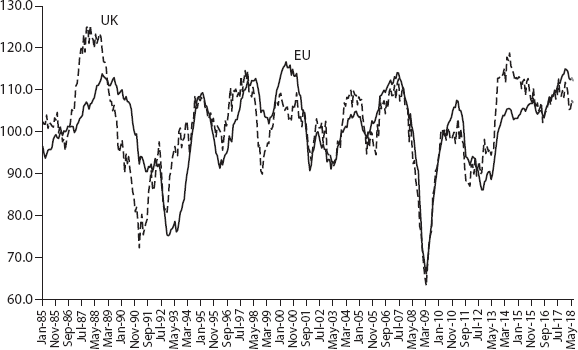

Figure 7.2 shows the Economic Sentiment Index (ESI) for the UK and the European Union as a whole, including the UK. This is a combination of surveys taken monthly by the European Commission in every country, combining reports from consumers, retail, construction, services, and industry. I like to think of this series as a perfect example of the economics of walking about—it summarizes the timely views of people and businesses. Sadly, academic economists pay little or no attention to such series, but they should. I plot the ESI from 1985 through 2018. It is clear that the two series move closely together. It turns out that France, Germany, and the UK all reached a peak around June 2007. A similar story of a big drop in the ESI by September 2008 was to be found in other major European countries, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. By the summer of 2008 it was apparent that something bad was amiss in Europe as well as the United States. Few spotted it.

Figure 7.2. European Commission’s monthly Economic Sentiment Index, EU and UK, 1985–2018.

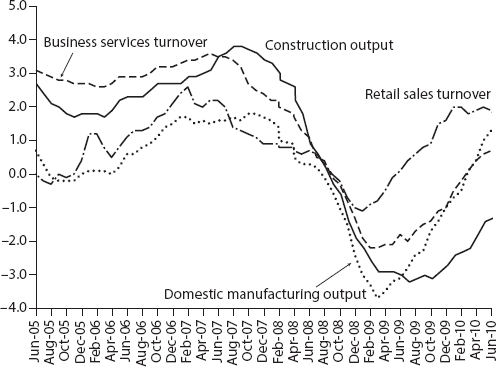

Other qualitative series showed similar patterns. This includes the Purchasing Manager Indices that are reported monthly for manufacturing, services, and construction. In the UK, the Bank of England’s agents report a series of scores they calculate from their visits to business contacts.24 Their scores for turnover, profitability, capacity constraints, and investment and employment intentions all started tumbling from around May 2007. Nobody much noticed. Well, some did.

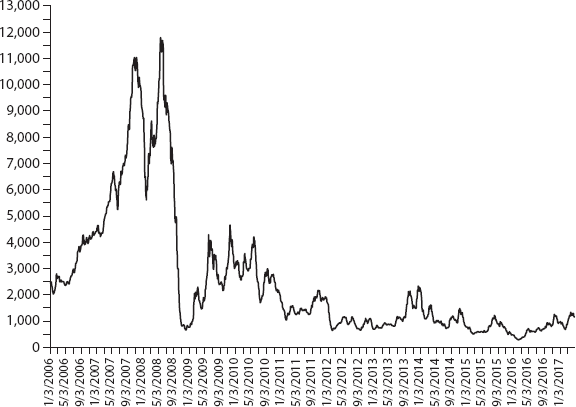

Figure 7.3. The Baltic Dry Index, 2006–17

Of special note here is the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), which collapsed in the fall of 2008 and has hardly recovered (figure 7.3).25 The Baltic Dry Index is issued daily by the London-based Baltic Exchange. The index covers Handysize, Supramax, Panamax, and Capesize, massive dry bulk carriers of a range of commodities around the world including coal, iron ore, and grain. BDI covers 100 percent of dry bulk cargo in transit on the world’s oceans but does not include ships transporting freight via container or transport of energy liquids by tanker.26 On May 20, 2008, the index reached its record-high level since its introduction in 1985, of 11,793 points. By September 1 it had dropped to 6,691 and nobody much noticed. Trade credit was increasingly becoming unavailable. Three months later, on December 5, 2008, the index had dropped by 94 percent, to 663 points, the lowest since 1986. At the time of writing, in November 2018, BDI was at 1,031, up from a low of 297 on February 5, 2016. It remains unclear what to make of this low level of the index or of its trebling over the last couple of years, but keep watching. It is a bad sign when economic indicators fall by 95 percent in a few weeks.27

Another example of EWA is the regular report by the Bank of England agents. This report used to be monthly but has become less regular since the MPC stopped meeting monthly. These reports are roughly equivalent to the Beige Book in the United States, which reports on conditions on the ground from talking to firms. In 2007 and 2008 the scores they reported were plunging but nobody was taking much notice. At the time I recall saying to the staff who were gathered to brief the MPC at one of our Friday pre-MPC meetings in the spring of 2008 that the problem with the agents is they don’t believe the agents. They had been so pounded by the economists. In the regular Friday briefing they would have ten minutes or so at the end. They spotted early that recession was coming.

Figure 7.4. Bank of England agents’ scores, 2005–10. Source: Bank of England, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/about/people/agents.

Figure 7.4 illustrates. It plots four scores out of the thirty or so the bank’s agents produce. These four are illustrative and the others follow a similar pattern. They all plunged together from around June 2007. By August 2008 each was in free fall. The Bank of England’s August 2008 Inflation Report said, “Reports from the Bank’s regional Agents point to broadly flat output in the third quarter.” No, they didn’t. There was no mention of the plunge in essentially all thirty scores including employment intentions, recruitment difficulties, capacity constraints, domestic prices, material costs and investment intentions, turnover, and output. All of them. The evidence of a sharp downturn was in plain sight. The data were moving fast to unprecedented territory.

The minutes of the MPC meeting of August 6–7, 2008, where I voted for a 25 basis point cut and everyone else voted to do nothing, said, “The main questions for the Committee were the likely degree of persistence in inflation and how much spare capacity would be needed to offset that persistence.”28 That was not the main question. My view was different: “For another member, the downside risks to activity growth were greater than the majority view expressed in the Inflation Report. For this member, there was less risk of inflation being persistent and more risk of undershooting the inflation target in the medium term, because of rapidly slowing activity, so an immediate cut in Bank Rate was warranted.”29

Spotting the Recession

By the spring of 2008 I was becoming increasingly frustrated that nobody much else had spotted the fact that the major economies were slowing fast. What was happening in New Hampshire was starting to happen in the UK and other European countries I was visiting. There was some benefit of my flights every three weeks across the Atlantic. I decided to give a speech to the David Hume Institute at the Royal Society in Edinburgh on April 29, 2008, setting out my thoughts. In the speech I essentially said that recession had arrived in the United States and the UK using the economics of walking about. At the dinner afterward in Edinburgh participants from various financial firms wanted to talk about the possibility that one of Nicholas Taleb’s black swan events was coming to the United States, the UK, and globally. The discussion was prescient. Lots of people, including members of the MPC, said, who could have known recession was coming? The speech is still downloadable from the Bank of England’s website.30

At the start of the speech I said that I am a strong believer in Hume’s own view that we should not seek to solely explain events and behavior with theoretical models; rather, as Hume wrote in 1738 in his Treatise of Human Nature, we should use “experience and observation,” that is, the empirical method. My theme was that the UK was exhibiting broad similarities to the U.S. experience, essentially drawing on the evidence from the economics of walking about. I argued this suggested that in the UK we were also going to see a “substantial decline in growth, a pick-up in unemployment, little if any growth in real wages, declining consumption growth driven primarily by significant declines in house prices. The credit crunch is starting to hit and hit hard.”

I set out four phases of the downturn the United States had already been through and suggested the same was true of the UK, which was already in stage three and approaching stage four. I presented the data that I had available at the time, which are in the appendix (table A.1). This is relevant as it tells us what I knew at the time. It seemed clear to me that the United States was already in recession and the UK was heading there: “For some time now, I have been gloomy about prospects in the United States, which now seems clearly to be in recession,” and “I believe we face a real risk that the UK may fall into recession.” With hindsight, it looks broadly right. The United States went into recession in December 2007; the UK and most of the rest of Europe followed in April 2008.

I repeat here, verbatim, what I wrote in April 2008, the month we now know the UK went into recession.

Phase 1 (January 2006–April 2007). The housing market starts to slow from its peak around January 2006 (columns 1 and 2). Negative monthly growth rates in house prices start to appear from the autumn of 2006.

Phase 2 (May 2007–August 2007). Substantial monthly falls in house prices and housing market activity including starts (column 3) and permits to build (column 4) are observed from late spring/early summer of 2007. Consumer confidence measures (columns 5 and 6), alongside qualitative labor market indicators, such as the proportion of people saying jobs are plentiful (column 7), started to drop precipitously from around September 2007.

Phase 3 (September 2007–December 2007). Average hourly earnings growth (column 8) starts to slow from September 2007 as does real consumption (column 11). The growth in private non-farm payrolls starts to slow (column 8). House price and activity declines speed up.

Phase 4 (January 2008–). By approximately December 2007 the housing market problems have now spilled over into real activity. The United States seems to have moved into recession around the start of 2008. There have been big falls in house prices. In March 2008 housing starts were at a seventeen-year low. Foreclosure filings jumped 57 percent in March compared with the same month last year. One out of every 139 Nevada households received a foreclosure filing last month. California was second with a rate of one in every 204 homes, with Florida third with a rate of one in every 282 being hit with a foreclosure filing. Mortgage application volume fell 14.2 percent during the week ending April 18, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s weekly application survey. Refinance volumes fell 20.2 percent on the week.

Nominal retail sales (column 10) and real personal disposable income (column 12) have both fallen sharply since the start of the year. Real annual GDP growth in 2007 Q4 is now down to +0.1 percent, from 1.2 percent in 2007 Q3.

Spending on big-ticket items in the United States is tumbling. For example, Harley-Davidson, the biggest U.S. motorcycle maker, is cutting jobs and reducing shipments to dealers amid declining sales. Harley sold 14 percent fewer bikes in the United States in the first three months of the year [2008] than in the same period in 2007. U.S. automakers such as GM and Ford reported double-digit U.S. sales declines in March [2008] as demand for trucks and sport utility vehicles plummeted, with consumers holding back because of concerns about gas prices, the housing slump, and tightening credit. Even McDonald’s Corp., the world’s biggest restaurant company, has seen U.S. comparable-store sales fall 0.8 percent in March 2008, the first decline since March 2003.

The most recent labor market data release for the United States, for March 2008, showed the biggest drop in payrolls in five years, while applications for unemployment benefits are on the increase. The benefit claims average for the past two months has already risen to a level similar to where it was at the start of the 2001 recession and with no sign of bottoming out. Unemployment jumped from 4.8 to 5.1 percent with particularly large increases for the least educated.

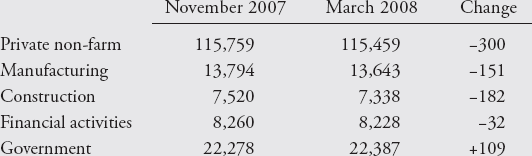

Declines in employment to this point in the United States have been concentrated in manufacturing, construction, and financial activities. The numbers below report the declines by industry grouping and are in thousands, seasonally adjusted between November 2007 and December 2008. Private-sector non-farm payrolls over this period have fallen by three hundred thousand with a decline of more than 60 percent of the job loss from construction, even though it accounted for only 6.5 percent of the stock at the start of the period.

I then showed similar evidence for the UK, with the data presented in the appendix (table A.2).

Phase 1 (August 2007–October 2007). House prices start to slow in 2007 Q2 and 2007 Q3 (columns 1, 2, and 3). Housing activity measures also slow (columns 4 and 5) from around October 2007.

Phase 2 (November 2007–January 2008). Consumer confidence measures start slowing sharply also from around October 2007 (columns 6, 7, 8, and 9). The qualitative labor market measures such as the REC Demand for Staff index also start slowing from around October 2007.

Phase 3 (February 2008–). In early 2008 the Halifax index and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) survey both suggest that house-price falls have started to accelerate. The Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) recently announced that mortgage lending in March was down 17 percent on the year. Loan approvals are down, and the RICS ratio of sales to stocks is down from .38 in September 2007 to .25 in March 2008. Bradford and Bingley, Britain’s biggest buy-to-let lender, has recently reported that some borrowers are finding it hard to repay their loans, so mortgage arrears are growing, reminiscent of what has been happening in the United States.

The latest figures showed that the number of people whose homes were repossessed in 2007 went up by 21 percent. The CML said 27,100 homes, the highest figure since 1999, were taken over by lenders after people fell behind with repayments. According to data published by the British Bankers’ Association the number of mortgages granted to homebuyers dropped last month by 47 percent below the same month last year to its lowest level in more than a decade. Some 35,417 mortgages were approved for home purchase in March, compared with 43,147 in February, a drop of 18 percent.

Hourly earnings growth is sluggish—both the AEI and LFS measures are slowing. Total hours and average hours started to fall in early 2008. Claimant count numbers for February 2008 are revised up from a small decline to an increase. There is a growth in the number of part-timers who say they have had to take a full-time job because they couldn’t find a part-time job—up 37,000 in March alone. Even though the number of unemployed has fallen, the duration of unemployment appears to be rising, which means that the outflow rate from unemployment has fallen. The number unemployed over six months in March 2008 was up 22,000 while the number unemployed for less than six months was down 47,000.

As in the United States, recent declines in employment in the UK are concentrated in manufacturing, construction, and financial activities. The numbers presented below are in thousands, seasonally adjusted, and relate to the number of workforce jobs. The quarterly data relate to the period September–December 2007 while the annual data refer to December 2006–December 2007.

Change on quarter |

Change on year |

|

All jobs |

+ 13 (0.0%) |

+208 (0.7%) |

Manufacturing |

29 (-0.9%) |

-53 (-1.6%) |

Construction |

-19 (-0.9%) |

-7 (-0.3%) |

Finance & business services |

-5 (-0.1%) |

+ 149 (2.3%) |

Phase 4 is coming. More bad news is on the way. I think it is very plausible that falling house prices will lead to a sharp drop in consumer spending growth. Developments in the UK are starting to look eerily similar to those in the United States six months or so ago. There has been no decoupling of the two economies: contagion is in the air. The United States sneezed and the UK is rapidly catching its cold…. I have identical concerns for the UK. Generally, forecasters have tended to underpredict the depth and duration of cyclical slowdowns.

At his Mansion House speech of June 18, 2008, with the UK in its third month of recession, Bank of England governor Mervyn King had it totally wrong. No mention of recession and inflation was about to plummet like a rock. Oh dear.

The fact that growth and inflation are heading in opposite directions has led some commentators to question our monetary framework. Target growth not inflation is the cry. I could not disagree more. This is precisely the situation in which the framework of inflation targeting is so necessary. Without it, what should be a short-lived, albeit sharp, rise in inflation, could become sustained. Without a clear guide to the objective of monetary policy, and a credible commitment to meeting it, any rise in inflation might become a self-fulfilling and generalised increase in prices and wages. And surely the lesson of the past fifty years is that, when inflation becomes embedded, the cost of getting it back down again is a prolonged period of sluggish output and high unemployment. Price stability—returning inflation to the target—is a precondition for sustained growth, not an alternative.

Price stability was not a precondition for anything, let alone sustained growth. It turns out targeting inflation meant too many policymakers failed to spot the biggest recession in a generation. Since then we have continued to have a growth problem and a “too little” inflation problem. Deflation replaced inflation as the new problem central bankers faced, but they have failed to adapt. The crisis was totally predictable using the EWA. Focusing on inflation meant policymakers took their eyes off what was happening in the real world. The CPI, which was the measure the MPC was supposed to target and keep at 2 percent, was 5.2 percent in September 2008 but only 1.1 percent in September 2009.

Reading the speeches of central bankers and examining the minutes of their meetings along with forecasts, especially during 2007 and 2008, doesn’t give one confidence that they know what they are doing. Things have not been much better since.

What Has Been Learned from the Crisis?

Not much. Same old, same old.

I was on a panel at the beginning of 2018 where the two other participants forecast that GDP growth in the United States would be well over 4 percent, as claimed by Trump, driven by the GOP tax cut. I noted that the

December 2017 forecasts of the FOMC, the OECD, the IMF, and the

World Bank that came out the next day were all up slightly from earlier in 2017.31 All were around 2.5 percent or so and slowing to about 2.2 percent by 2020 and 2021. The problem since 2010 is that central bank forecasts have been too optimistic; now the claim is they are overly pessimistic. Nobody trusts economic forecasters anymore. They prefer guesswork.

In April 2018 the markets had fully priced in a rate rise by the MPC at their May 2018 meeting. This was based on comments by members including Mark Carney. It was clear, though, that there were no actual data to back up the need for a rate rise; it was being driven by results from their (hopeless) models. The same ones that failed to spot the Great Recession in the first place, and likely the same modelers too. By the meeting itself, held in May, probabilities of a rate rise fell to 8 percent and the MPC did nothing. In the meantime, data turned bad with GDP growth of 0.1 percent for 2018 Q1 and weak PMIs as well as declining inflation, investment, and retail sales. GDP in the UK grew 1.1 percent in the first three quarters of 2018, but quarterly GDP growth in Q4 was only 0.2 percent. Brexit uncertainty appears to have slowed activity, and by 2019 talk of rate raises has gone.

There remains some disagreement among central bankers on what is happening, but when it comes to votes on rate rise they are almost always unanimous. In a speech on June 4, 2018, new external MPC member Silvana Tenreyro discussed the importance of models, although she didn’t mention how awful their forecasting record has been: “I expect that the narrowing in labour market slack we have seen over the past year will lead to greater inflationary pressures, as in our standard models,” despite the fact that the MPC has been saying that for the last five years and it hasn’t happened. She concluded that “we should keep working on our models because they do help our thinking—even though they will never predict everything in advance—we might know better how to respond to events once they occur.”32 The models were great, but sadly the real world didn’t comply.

Sir Jon Cunliffe, deputy governor at the Bank of England, took a somewhat more dovish tone, arguing in a November 2017 speech that there was likely more capacity in the UK labor market because of underemployment:

A straightforward explanation of why pay growth is subdued at very low levels of unemployment is that we are under-measuring the amount of spare capacity—or “slack”—in the labour market. Recent trends in the world of work have meant greater (voluntary and involuntary) self-employment and part-time employment. Measures incorporating under-employment as well as unemployment—i.e., how much more people who are in work would like to work—may give a better indication of the amount of spare capacity in the labour market. In such a world, low pay is simply telling the policy maker that there is more labour market slack than the unemployment indicators are registering, that the output gap is larger than thought and that the economy can grow at a faster rate without generating domestic inflation pressure.33

Inexplicably, in the end he voted for a rate rise in August 2018.

The MPC vote to raise rates on August 2, 2018, from 0.5 to 0.75 percent was unanimous, 9–0. The FOMC vote to raise the interest rates on required and excess reserve balances to 2.2 percent, effective September 27, 2018, was also unanimous, 9–0. Groupthink is back in town. In my view there were no data from the real world to justify either rate rise. In both cases I would have dissented.

Based on weak PMIs and slowing GDP growth the Eurozone (EZ) appears to be slowing. However, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) inflation in the EZ picked up due to a rise in energy prices to 2.2 percent but only to 1.3 percent excluding energy in October 2018, the same as it was in August and September. Eurostat data releases in October 2018 showed production in the EZ construction was down 0.5 percent. The flash estimate of GDP growth in the euro area was 0.2 percent in 2018 Q3, down from 0.4 percent in the previous two quarters.34 The annual growth in wages in the EZ in the second quarter of 2018 was 1.9 percent, versus 1.8 percent in 2018 Q1, 1.6 percent in 2017 Q4, and 1.7 percent in 2017 Q3. In Germany in 2018 Q2 wage growth was 2 percent and in France it was 1.8 percent.35

The Financial Times reported that, despite the fact there was no evidence in the data of any rise in wage growth in the EZ, Peter Praet, ECB chief economist, said the “underlying strength” of the Eurozone economy has bolstered his confidence that inflation will move toward the central bank’s objective, highlighting policymakers’ view that recent weakness is transitory.36 The ECB executive board member said there is “growing evidence that labour market tightness is translating into a stronger pick-up in wage growth,” according to prepared remarks to the Congress of Actuaries in Berlin. So, a 2 percent wage norm means that rates should rise?37

The Financial Times also quoted Jens Weidmann, president of Germany’s Bundesbank and a member of the ECB’s governing council, who echoed Mr. Praet’s bullish take on inflation, claiming it is “now expected to gradually return to levels compatible with our target.” He added that market expectations that the ECB will halt its vast bond-buying program by the end of this year “are plausible.”38 Inflation in the Eurozone in January 2019 was 1.4 percent, while only three out of nineteen member countries had inflation rates of over 2 percent. The clueless hawks haven’t gone away.

A speech from Sabine Lautenschläger, member of the executive board of the ECB and vice chair of the supervisory board of the ECB, gave me hope. I am not sure that she can be confident that the euro area is not at a turning point, as that is hard to call even when you are at one as we found in 2007 and 2008. It is worth quoting a chunk of her speech in full as it looks broadly right.

So we are seeing that the pace of growth has become more moderate, but we are not seeing a turning point. We remain confident in the strength of the economy.

After all, the things that are currently holding back growth seem to be temporary. There was the early timing of the Easter break, there was a strong outbreak of flu in some parts of the euro area, there was cold weather and there were strikes in some countries. All this weighed on growth, but it won’t do so permanently.

We need to keep a close eye on all this, and we will. But for now, there is no need to rewrite the story. The economic expansion remains solid and broad-based. Financing conditions are good, the labour market is robust with a historically high increase in jobs, and income and profits are growing steadily. In short: the real economy is doing well.

By contrast, inflation so far does not seem to be recovering as convincingly. This has left many observers scratching their heads as to why the current level of low inflation does not match the current state of the real economy. It seems that inflation is responding less to the slack in the economy than would be expected. This disconnect between the real and nominal sides of the economy is the subject of intense debate. In very general terms, there might be two forces at play. First, the Phillips curve might have changed. It might, for instance, have flattened, or it might have shifted downwards. Empirically, it is very hard to determine which—if either—of the two things has happened.

And that brings me to the second point, which is that we cannot be sure whether we are measuring slack correctly in the first place. The unemployment rate, for instance, is based on a narrow definition. Just think of people who work part-time. Officially, they are employed, but they could work more, of course. So, the amount of slack could be larger than we think. If that is the case, it’s no surprise that inflation has not kicked in.39

Sabine Lautenschläger at least has got it.

There are one or two EWA indicators that were flashing amber in the United States in mid-2018. The U.S. yield curve plots Treasuries with maturities ranging from four weeks to thirty years. The gap between long and short yields turning negative has been a reliable indicator of recession. The yield curve was flattening during the first few months of 2018. Ed Yardeni’s Boom-Bust Barometer, which measures spot prices of industrial inputs like copper, steel, and lead scrap divided by initial unemployment claims, fell before or during the last two recessions. Housing starts and building permits have fallen ahead of some recent recessions. The Census Bureau reported in October 2018 that in the United States private-owned housing units authorized by building permits in September 2018 were down 0.6 percent compared with August. Privately owned housing starts were down 5.3 percent on the month. Privately owned housing completions were 4.1 percent down on the month.40 Megan Davies also notes that risk premiums on investmentgrade corporate bonds over comparable Treasuries have topped 2 percent during or just before six of the seven U.S. recessions since 1970. Spreads on Baa-rated corporate bonds rose to 2 percent in July 2018.41

Nic Fildes has reported on difficulties since the Brexit vote in June 2016 in the UK high street.42 Spending, which held up after the Brexit vote through dis-saving and borrowing, has now started to fall. This is to be expected given that real wages in the UK are down 5 percent since 2008 and didn’t change at all between March 2016 and March 2018, which are the latest data available.

According to the ONS, in 2017 UK households saw their outgoings surpass their income for the first time in nearly thirty years. On average, each UK household spent or invested around £900 more than they received in income in 2017, amounting to almost £25 billion (or about one-fifth of the annual National Health Service [NHS] budget in England). Households’ outgoings last outstripped their income for a whole year in 1988, although the shortfall was much smaller at just £0.3 billion. Even in the run-up to the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009—when 100 percent (and more) mortgages were offered to home buyers without a deposit—the ONS noted, the country did not reach a point where the average household was a net borrower.43

House of Fraser and Marks and Spencer are expected to shed dozens of stores in 2018, while Next, the clothing retailer, is looking at inserting a clause into its property leases to lower its rent. Toys “R” Us, Calvetron Brands, which owns women’s wear chains including Jacques Vert and Precis, and the electronics retailer Maplin have all entered administration. Mother-care and Carpetright are also in trouble. The children’s goods retailer revealed plans to close fifty stores while Carpetright, Fildes reports, has been forced to pursue a rescue rights issue after closing ninety-two stores. Fast-fashion chain New Look also plans to close up to sixty stores while food chains Prezzo, Jamie’s Italian, and Byron Burger have also closed outlets. N. Brown, a Manchester-based company that has been operating since the 1850s, has begun a consultation process to close its remaining twenty high street stores.44 Not good.

The collapse of the Wolverhampton-based Carillion, the UK’s second-biggest construction company (whom I used to work for when they were called Tarmac), at the start of 2018, with its 45,000 workers, of whom 20,000 were in the UK, sent shock waves around the UK.45 It holds a number of government contracts, including for the construction of a highspeed rail link and for the maintenance of roads.46 Carillion found it harder and harder to borrow. This feels like 2008 all over again.

The liquidation threatens the jobs of more than 43,000 British workers, including those who are in partnership with Carillion, which suggests still others may go under. Carillion as well as hundreds of contractors and subcontractors.47 Its shares had dropped 90 percent in 2017, it issued profit warnings, and it was on its third chief executive within six months.48 Carillion had been awarded large public-sector contracts of over £2 billion by the UK government and an open question is why, given that it was under investigation by Britain’s financial watchdog.49

I suspect this isn’t going to go down well with the general public. A Guardian editorial on what they call “reaping the consequences of corporate greed” noted the extent of the impact the failure of Carillion is likely to have on jobs. The government has promised that Carillion’s public-sector contracts will continue to operate, under the Official Receiver’s control, following the liquidation. But private-sector contracts—which make up 60 percent of Carillion’s business—are only guaranteed for forty-eight hours. After that, they could be terminated. Maybe this is a one-off, but it probably isn’t. Four Seasons Health Care, the UK’s second-largest home health-care business, reported large third-quarter losses, blaming public spending cuts and a Brexit-related shortage of nurses.50 The question is, are these two cases the start of something big and bad?

Worryingly, on January 29, 2019, the Conference Board released their Consumer Confidence Index for the United States, which decreased in January, following a decline in December. The index now stands at 120.2 (1985 = 100), down from 126.6 in December and 136.4 in November. The Present Situation Index—based on consumers’ assessment of current business and labor market conditions—declined marginally, from 169.9 to 169.6. Of particular concern is that the Expectations Index—based on consumers’ short-term outlook for income, business, and labor market conditions—decreased from 112.3 in November to 97.7 in December and 87.3 in January. The question is whether this decline is the start of a trend downward as occurred at the start of the Great Recession.

This generally isn’t what happens at full employment. Nothing much has changed since 2008. More fiddling about by policymakers. This was all eminently foreseeable. But the biggest downturn wasn’t spotted until many months after it had started, and as a consequence people suffered. The economic forecasting models failed and continue to fail. Policymakers ignore the economics of walking about at their peril. Why should we trust any of them now? I don’t.