CHAPTER 9

Somebody Has to Be Blamed

When people are hurting they seem to want someone to blame. Immigrants will do. In tough times the outsider is easy to blame. Immigration is a divisive political issue around the world. Bloody foreigners. As Bob Dylan sang, “pity the poor immigrant.”

Mexicans, Poles, and Muslims will do. The Jews were the scapegoats in the 1930s. There is clearly a perception among those who voted for Trump that the influx of foreigners from Mexico and elsewhere took jobs away. In the UK there was considerable opposition to the flow of immigrants to the UK led by the UK Independence Party (UKIP), and this was central to the Brexit campaign—keep Britain British. There were growing fears of terrorism and the fear that refugees might do bad stuff.

As can be seen in the table below calculated from the OECD’s “International Migration Outlook, 2018” (table 1.1), the inflow of permanent immigrants in 2016 compared to 2010 was up in percentage terms, nearly fourfold in Germany, and more than doubled in Austria and Sweden. Countries are ranked by the percentage change in the flow. They have fallen substantially in Italy, the UK, Spain, and Portugal.

Germany |

372 |

Poland |

161 |

Greece |

143 |

Austria |

130 |

Sweden |

107 |

Ireland |

79 |

Korea |

78 |

Japan |

71 |

Denmark |

62 |

Netherlands |

51 |

Mexico |

32 |

France |

17 |

New Zealand |

15 |

United States |

13 |

Switzerland |

9 |

Australia |

7 |

Canada |

5 |

Norway |

2 |

Belgium |

-14 |

Portugal |

-18 |

United Kingdom |

-22 |

Spain |

-23 |

Italy |

-52 |

Slovakia |

-71 |

There was a huge public outcry when the Trump administration implemented a policy to separate immigrant children from parents crossing the southern border illegally. Pictures of crying youngsters who had been separated from their parents and imprisoned didn’t go over well. Former First Lady Laura Bush in an op-ed in the Washington Post argued that “our government should not be in the business of warehousing children in converted box stores or making plans to place them in tent cities in the desert outside of El Paso. These images are eerily reminiscent of the Japanese American internment camps of World War II, now considered to have been one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history.”1 Michael Steele, former Republican National Committee chairman, called them concentration camps.2 General Michael Hayden, former director of the CIA, tweeted a picture of a Nazi concentration camp and the words “other governments have separated mothers and children.” Emotions are running high.

Majorities in most countries, though, including the UK and the United States, do remain supportive of immigration, but there is significant and vocal opposition. Support for immigration tends to be highest in the big cities where the immigrants live. Paris voted against Frexit; Washington, D.C., and New York voted for Clinton; and London voted to Remain. Most opposition is found where the immigrants don’t live, for example, in rural areas in the United States. In European countries with more asylum seekers from Iraq and Syria—Germany and Sweden—people tend to view immigrants as less threatening. There is a good deal of concern about the big rise in Muslim asylum seekers, especially given the terror attacks that have taken place in France, Germany, and the UK. Terrorism is a growing concern.

Migrants, who are a highly selected, mobile, and motivated group, add more to an economy than they take from it. In general, there is a mover’s premium; the best move. In academia the best people are able to get offers at other institutions to raise their salaries, and you have to pay people more to move to compensate for the disruption and an adjustment period. Movers grease the wheels of the labor market, as they are more mobile and often more productive than the indigenous population and can move to where the work is. Immigrant populations have likely improved the workings of the labor markets in host countries and have kept prices down for a number of items, for example, fruit and vegetables, which benefits everyone. But the left-behinds with low skills are threatened as they are the most impacted. The gainers didn’t compensate the losers enough.

Unsurprisingly, the central plank of populist uprisings in the years after the Great Recession has been an opposition to immigration. Immigration is a prime example of where there is a striking juxtaposition between perception and reality. Crime among immigrants, for example, is lower than among the indigenous populations, but the majority of the public seems to believe the reverse. There is a widely expressed fear that immigrants are taking high-paying jobs away as they are prepared to do them more cheaply than would indigenous workers.

I am an immigrant. I have been in the United States for nearly thirty years but have never lost my accent. I am asked all the time where I am from. I know what it’s like to be told to go home—well, a bit.

I arrived in the United States with my two daughters on July 3, 1989. The Irish writer George Bernard Shaw once said: “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.” It took a long time to work out where to buy things. There were no public toilets or fish and chip shops. I couldn’t find a tire shop in the phone book as I kept looking up “tyre.” Nobody could help me find an ironmongers. The supermarket was a huge culture shock as we had no idea what brands to buy. I couldn’t work out why nobody came to collect the rubbish and I missed gritting lorries and pubs. I can only imagine how hard it is for those who don’t speak the lingo. It took me many months to understand the rules of baseball. After a couple of months at Dartmouth my secretary asked me if they celebrate Christmas in Britain. Geraint Johnes, professor of economics at Lancaster University with whom I shared an office in graduate school in Cardiff, tells me his culture shock story involved going to the post office in 1984 to send a telegram and being told they didn’t do that—he had to find a florist.

I am proud to be an immigrant too. I have been told on a few occasions to go back to England if I don’t like the way things are done here. I have a son who was born here who is an officer in the U.S. Army Reserve and is a proud American. My U.S. passport is the same as everyone else’s. I remember before I became a citizen I had a green card. I was chatting with a very nice immigration officer at the Boston airport who told me that a green card was an important document. “Anyone can get a passport,” he told me, “but we checked you out!”

I do recall, though, at the interview for the green card, the INS officer asked my three-year-old and five-year-old daughters whether they were promised brides. Both started crying. I wasn’t happy, and my attorney told me to be quiet! My eldest daughter was sixteen in November 2001 and took drivers ed at school that term and went with everyone else to the local test center. She was mortified to be told that she couldn’t take the test there as she was an alien and had to go to the Alien Driving Test Center in the state capital, Concord. It apparently had been established after 9/11. The guy giving the driving tests asked her if she had ever driven in Concord, and she replied that she hadn’t. He told her to park the car and that she had passed the test and loved her English accent. They never actually left the test center. It isn’t easy being an alien though.

My final green card story involves the border patrol. I picked up my twelve-year-old daughter from school on a winter’s night in my truck, towing a trailer with two snowmobiles on the back, headed down one exit on I-91 to the local place in Vermont to get them serviced. Post-9/11 border patrol had a checkpoint on the freeway watching for terrorists coming from Canada. I arrived at the checkpoint and the officer asked where I was going, and I said that I was going to the next exit to drop my snow machines off. He then asked if we were U.S. citizens and when I told him we were green card holders he asked to see them. Then the trouble really started. I had mine, but I had left my daughter’s card at home. The officer became rather angry and told my daughter she had to have her green card on her at all times and if not, she was subject to arrest. More tears. (Every parent knows what a great plan it would be to send a green card to school with a child each day.) Eventually the supervisor, who had kids of his own, apologized and let us go. There was a long line of cars on the freeway behind us. They never did catch any terrorists and they aren’t there anymore. The barrier was almost always closed when it was raining and there was another road that ran parallel to the freeway between the two exits that I always took after that. Brilliant. After all that nonsense, I decided it was time for us to become citizens, so we did. I can only imagine how hard it would be for an illegal immigrant who doesn’t speak the language.

Immigration was a huge issue in the Brexit campaign, not least when it was announced just before the vote that net migration had hit a record level of 333,000 in 2015. Prime Minister David Cameron had pledged to get that number down to under 100,000. Feelings are very strong in the United States about immigration and refugees. Donald Trump promised to build a wall along the Mexican border, that Mexico would pay for the deportation of 11 million illegal immigrants, and that he would ban Muslims from entering the United States. Mexicans who came to the United States were rapists, apparently. Immigration was also a major issue in the recent French presidential election.

The reality is a long way from the rhetoric. There is a lot of antipathy toward immigrants in the years of slow recovery after the Great Recession. Immigrants themselves disproportionately did not vote for Trump, Brexit, or Le Pen. Major towns and cities with high proportions of immigrants voted against also. The fear of immigrants appears to be highest in locations where they don’t live. It seems the fear of the foreigner who is known is much less than the fear of the unknown foreigner.

Immigration in the United States: Build That Wall

On December 7, 2015, Trump released a statement saying, “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.”3 Trump also called for a wall to be built on the Mexican border; the frequent cry from his supporters at his rallies was “build that wall” once they were done with chants of “lock her up.” Trump even claimed that Mexico was going to pay for it, which was always a non-starter and has now, conveniently, been dropped.

Not a single foot of new wall has been built since Trump took office in 2017. Ex-president of Mexico Vicente Fox Quesada made it clear to Trump on Twitter that Mexico was not going to pay for his “#f***ingwall.”

On July 29, 2018, Donald Trump tweeted, “I would be willing to ‘shut down’ government if the Democrats do not give us the votes for Border Security, which includes the Wall! Must get rid of Lottery, Catch & Release etc. and finally go to system of Immigration based on MERIT! We need great people coming into our Country!” At that time the GOP controlled the House, the Senate, and the presidency. Shutting down the federal government to get funding for a wall in December 2018 didn’t work out so well for President Trump, who reopened the government with no concessions from the Democrats.

In a speech on June 16, 2015, Donald Trump labeled immigrants from Mexico “rapists” and criminals. “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people,” he said.4 Pity the poor immigrant, some of whom, presumably, are good people.

More than forty million people living in the United States were born in other countries, and almost an equal number have at least one foreign-born parent. The number of immigrants living in the United States increased by more than 70 percent, from 24.5 million or about 9 percent of the population, in 1995, to 42.3 million or about 13 percent of the population, in 2014. The native-born population increased by about 20 percent during the same period.

Immigrants are more geographically concentrated than natives. California, the state with the highest percentage of immigrants, hosts 25 percent of all U.S. foreign born but only 9 percent of its natives. New York, the metropolitan area with the highest percentage of immigrants, hosts 14.5 percent of all U.S. foreign born but only 5.5 percent of natives. Consequently, native individuals have a very different degree of exposure to immigrants depending on where they live. Among California residents, in 2011, for every two U.S. born there was one foreign born. At the other end of the spectrum, among West Virginia’s residents, for every 99 natives there was one immigrant.5

A Pew Research Center report in November 2016 estimated that there were 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States in 2014, a total that is broadly unchanged from 2009.6 The number peaked in 2012 at 12.2 million, or 4 percent of the U.S. population. The workforce includes around 8 million illegals. Six states accounted for 59 percent of illegal immigrants: California, Texas, Florida, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.7 In a recent report Pew noted that the number of U.S.-born babies with unauthorized parents has fallen since 2007. About 250,000 babies were born to unauthorized immigrant parents in the United States in 2016, the latest year for which information is available, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data. This represents a 36 percent decrease from a peak of about 390,000 in 2007.8

The demographics of illegal migration on the southern border have changed significantly over the last fifteen years: far fewer Mexicans and single adults are attempting to cross the border without authorization, but more families and unaccompanied children are fleeing poverty and violence in Central America. In FY17, approximately 58 percent of U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions were individuals from countries other than Mexico—predominantly individuals from Central America—up from 54 percent the previous year. Of the 310,531 apprehensions nationwide, 303,916 were along the southwest border. Of those, 162,891 were from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Another 127,938 were from Mexico. Of those apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol, 10 percent had been apprehended on at least one other occasion in FY17, down from 12 percent in 2016. Notably in 2017 Customs and Border Protection recorded the lowest level of illegal cross-border migration on record, as measured by apprehensions, which had averaged over 1 million per year between 1980 and 2016.9

It is also possible to determine how many people overstay their visas. In 2015, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) determined that there were nearly 45 million non-immigrant admissions to the United States for business or pleasure through air or sea ports of entry who were expected to depart in FY2015. Of this number, DHS calculated a total overstay rate of 1.17 percent, or around half a million individuals. The overstay rate was especially high for visitors from Afghanistan (10%), Bhutan (24%), Georgia (12%), Iraq (6%), Sudan (7%), and Yemen (6%). It was 0.4 percent for the UK, 0.7 percent for France, and 1 percent for Germany. For Canada and Mexico, the overstay rate for FY2015 was 1.18 percent and 1.45 percent of the expected departures, respectively, through air and sea ports of entry. A wall would likely increase the number of people overstaying their visas.10

A recent paper has looked at the rise and fall of the numbers of low-skilled immigrants to the United States.11 The authors note that after the “epochal” wave of unskilled immigrants from the 1970s to the 2000s, the numbers have slowed since the Great Recession. The number of undocumented immigrants has declined in absolute terms, while the overall population of low-skilled foreign workers has remained stable. The authors found that the immigration wave of the late twentieth century was enabled to a substantial extent by the rapid growth of the labor supply in Latin America and the Caribbean relative to the United States. Because labor-supply growth in migrant-sending nations is slowing and will continue to slow, the demographic push for U.S. immigration is abating.

The authors also suggest that the weakening of these migration pressures that began in the early 2000s may have been masked by the temporary labor-demand boost provided by the U.S. housing boom. The resulting post-2007 slowdown in low-skilled immigration, the authors find, is of a magnitude consistent with a decrease in the wage gap between high-skilled and low-skilled U.S. labor of 6 to 9 percentage points. If, as predicted by demographic forces, low-skilled immigration continues to decline in future decades, U.S. firms, especially those located in U.S.-Mexico border states and in the immigrant-intensive industries of agriculture and construction, eating and drinking establishments, and nondurable manufacturing, “are likely to face pressure to alter their production techniques in a manner that replaces low-skilled labor with other factors of production” (Hanson, Liu, and McIntosh 2017, 44).

Places with the fewest immigrants push back hardest against immigration.12 In the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump carried twenty-six of the thirty states where the share of residents born abroad is the smallest, according to the five-year (2011–15) estimates from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Native-born residents account for 91 percent of the population in states Trump won versus 81 percent in states he lost.

A poll released by Ipsos Mori in the UK that was conducted June 11–14, 2016, just three days before the Brexit vote, found that more than 46 percent thought that EU immigration had been good rather than bad for the economy.13 There are stark differences between those who intended to vote to Leave and those who intended to vote to Remain regarding their views on immigration. Sixty-five percent of Leave supporters said immigration had been bad for Britain as a whole, and just 19 percent said the opposite. Remain voters had mirror-image attitudes, with 62 percent saying immigration had been good for the country and just 20 percent saying it had been bad.

Strikingly, people aged 18–34 were twice as likely as those over 55 to think EU immigration had been good for Britain (50 percent compared with 25 percent). Remain supporters were twice as positive as Leave voters on whether Britain had benefited from EU immigration economically with seven in ten saying the effect on the economy had been good, compared to 28 percent of Leave voters.

A survey by Opinium found that among people 18–24, reducing numbers coming into the UK was last among twenty-two priorities with the availability of jobs, protection of human rights, and well-funded public services their main concerns. When asked to rate Brexit priorities on a scale of 0 to 10, reducing immigration from the EU scored just 5.85 among 18- to 34-year-olds, below the need to share arts and culture between EU countries (6.34, in twenty-first place) and reducing poverty (6.21, nineteenth place).14 A survey by Ipsos Mori found that people in the UK over the period 2015–16 viewed the impact of immigration more positively but still wanted the overall number of immigrants to be reduced.15

A recent study examined data from the thirty-fourth British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) and found that when asked, “Do you think the number of immigrants to Britain nowadays should be [increased a lot, increased a little, remain the same as it is, reduced a little, or reduced a lot]?” 56 percent of respondents said “reduced a lot” and an additional 21 percent said “reduced a little.”16 But nearly three-quarters of those surveyed in the BSAS who were worried about immigration voted Leave, versus 36 percent who did not identify this as a concern. Roger Harding, head of the National Centre for Social Research, which examined the BSAS data, noted, “For leave voters, the vote was particularly about immigration and the social consequences of it.”17

One of the very striking things about the Brexit referendum was the distinction between the stock and flow elements of immigration. London, with a high immigrant stock, voted to remain, but Boston, with a low stock but high recent flow, voted to leave. Immigrants voted against Brexit. Immigrants voted against Trump. We can only speculate about the reasons for this, but two suggest themselves: the fear/shock of the new and the pressure on public services, particularly during a period of austerity.

Views on Immigration in the Rest of the World

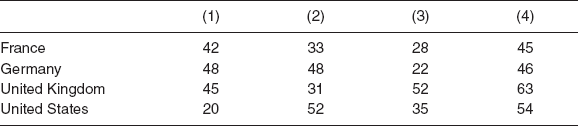

The 2013 International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) asked respondents across numerous countries about their views on crime rates among immigrant populations (table 9.1). The proportion of respondents who agreed or agreed strongly that immigrants increase crime rates are reported in the first column. The proportion was the lowest in the United States (20%). The second column reports on whether respondents felt immigration was good for the economy; the United States is highest at 52 percent versus 31 percent in the UK, 33 percent in France, and 48 percent in Germany. A high proportion of U.S. respondents are also supportive of free trade (54%). Column 3 shows that respondents in the UK are twice as likely to report that immigrants take away jobs from the native born than in the other three countries. Column 4 shows respondents are broadly split on the merits of free trade in all four countries, with the biggest support in the UK.

In addition to immigration, people around the world are also concerned about terrorism coming from abroad. For the last several decades Gallup has asked people around the world the following question: “How worried are you that you or someone in your family will become a victim of terrorism—very worried, somewhat worried, not too worried or not worried at all?” In December 2015, after the deadly attacks in Paris, the proportion saying “very worried” was 19 percent, which was the highest since September 2001.18 Americans also reported in December 2015 that terrorism was the top issue facing the United States—Gallup found that 16 percent identified terrorism as the most important problem. By October 2016 Americans’ views of the most important problem had shifted to the economy (17%), dissatisfaction with government (12%), and race relations (10%), with terrorism in ninth place (5%).19

Table 9.1. ISSP 2013 Views on Immigration: Percentage Who Agree or Agree Strongly

(1) Immigrants Increase crime rates. (2) Immigrants are generally good for the economy. (3) Immigrants take jobs away from people who were born in our country. (4) Free trade leads to better products becoming available.

Source: http://www.issp.org/menu-top/home/.

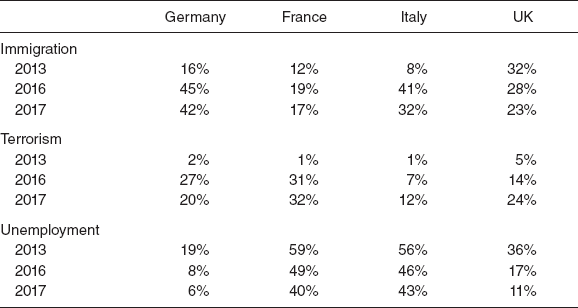

Respondents in the Eurobarometer Survey series conducted by the European Commission were asked to identify the two most important problems in their country. A dozen or so options were available; table 9.2 plots the three most important: immigration, terrorism, and unemployment. In a previous paper (Blanchflower et al. 2014), my colleagues and I found that unemployment was the most important concern expressed by respondents across EU countries, but this has changed with the influx of refugees into Germany and terror attacks in France and Belgium. The table plots data drawn from three Eurobarometers, for November 2013, 2016, and 2017. Immigration was the most important in Germany (45%) in 2016, but the fear had dissipated somewhat by 2017 as it had in the UK. The fear of terrorism picked up sharply in all four countries between 2013 and 2017. Unemployment remained the most important problem in 2017 in Italy and France but less so than it was in 2013.

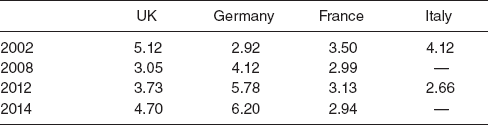

Table 9.3 reports the evidence from the 2002–14 European Social Surveys of answers to the question, “Is immigration bad or good for the economy?” on a scale of 1 to 10. Over the course of the surveys an increasing number of people in Germany said that immigration was good for the economy, while in the UK, France, and Italy, the trend was in the opposite direction, with a low point in 2008.

Table 9.2. “What Do You Think Are the Two Most Important Issues Facing [Our Country] at the Moment?”

Source: Eurobarometers #80.1 (November 2013); #86.2 (November 2016); and #88.3 (November 2017). https://www.gesis.org/eurobarometer-data-service/home/.

Table 9.3. Immigration Bad or Good for Country’s Economy

Bad for the economy = 1; Good for the economy = 10. Source: European Social Surveys, 2002–14, weighted.

In an interesting new paper Moriconi, Peri, and Turati (2018) explore the relationship between immigration and European elections between 2007 and 2016 in twelve countries using data from the European Social Surveys. They develop an index of “nationalistic” attitudes of political parties to measure the shift in preferences among voters when confronted with influxes of skilled and unskilled immigrants. Unsurprisingly they find that highly educated native voters are less nationalistic in their attitudes toward immigrants than the less-educated natives. Consequently, they find that larger inflows of highly educated immigrants dampen nationalistic sentiments, while larger inflows of less-educated immigrants heighten them. Their analysis shows strong nationalistic sentiments in regional pockets in the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, Demark, Sweden, Norway, and, especially, Italy. They conclude that immigration policies, producing more balanced inflows of less- and highly skilled migrants, would shift political preferences away from nationalist voting. These policies, they suggest, would not reduce immigration but rebalance it, allowing the pro-growth impact of immigrants.

On November 14, 2016, a UK polling company, Ipsos Mori, conducted an online survey of adults under the age of 65 in twenty-five countries called “What worries the world.” When asked, “Which topics do you find the most worrying in your country?” British respondents said, in order: immigration control (38%); health care (34%); poverty and social inequality (30%); rise of extremism (25%); terrorism (24%); and unemployment (20%). Out of the twenty-five countries Germany is most concerned about extremism, with 28 percent citing this as a worry versus 25 percent in Britain, 21 percent in France, and 11 percent in the United States.

According to the Pew Research Center’s report “Europe’s Growing Muslim Population,” published in November 2017, in 2010 in the EU there were 495.3 million non-Muslims, which fell to 495.1 million in 2016, whereas the number of Muslims rose from 19.5 to 25.8 million. The biggest increases over this period were in Germany (+1.7 million), the UK (+1.1 million), France (+1 million), and Italy (+700,000). Smaller European countries also had numerically smaller but significant increases. The population share of Muslims in many EU countries has risen sharply over these years. The table below lists changes in the percentage of Muslims in the population from 2010 to 2016 from the Pew report.20

2016 |

2010 |

|

Sweden |

8.1 |

4.6 |

France |

8.8 |

7.5 |

UK |

6.3 |

4.7 |

Belgium |

7.6 |

6.0 |

Germany |

6.1 |

4.1 |

Netherlands |

7.1 |

6.0 |

Austria |

6.9 |

5.4 |

Italy |

4.8 |

3.6 |

The rise in the Muslim share of the population is especially notable in Sweden and to a lesser extent in the UK, Austria, and Germany.

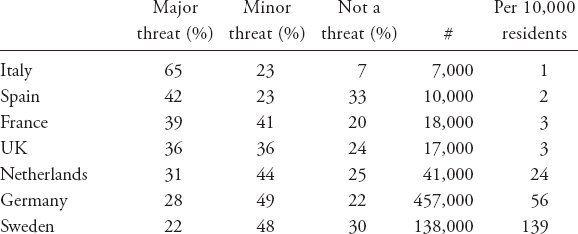

In the same report, Pew found that in countries with more asylum seekers from Iraq and Syria, the public’s perception of the threat they pose is relatively low.21 The table below reports the extent to which respondents in the 2017 Pew Global Attitudes Survey believe large numbers of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria represent a major, minor, or no threat to their country. In addition I report counts of asylum applications from Iraqis and Syrians between 2010 and 2016. In some European countries that have attracted large numbers of refugees from Iraq and Syria, such as Germany, public levels of concern about these refugees are relatively low. Meanwhile, in Italy, where there are fewer refugees from Iraq and Syria, a much higher share of the public says they pose a “major threat.”

To know them is to love them.

Immigration in the UK, Walking About, and the Maide Leisg

The United Kingdom was traditionally a net exporter of people until the mid-1980s, when it became a net importer of people. About 70 percent of the population increase between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, for example, was due to foreign-born immigration.

The UK now has the fifth-largest immigrant population in the world, at 8.5 million, doubling from 1990 to 2015.22 About 13 percent of the UK’s population is foreign born versus 14 percent in the United States, while a third of the UK’s immigrants are from the EU. In 2015 about 4.9 million people born in the UK, including me, were living in other countries, the ten largest in the world. Only 25 percent of the UK’s emigrant population lives in the EU.

There are many similarities between the flow of illegal immigrants especially from Mexico to the United States and the flow of legal workers from Eastern Europe to the UK since 2004. A major issue in the UK has been the rapid rise in the number of East Europeans who arrived in the last decade or so. In May 2004, eight Accession countries (A8)—the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, and Slovak Republic—were admitted to the EU, along with tiny Malta and Cyprus (AC-10). On January 1, 2007, Bulgaria and Romania (A2) also joined the EU. All of these countries entered a seven-year period of adjustment where residents would not have full rights to live and work in the rest of the EU. The UK Labour government decided to give the A8 rights to work in 2004, while the A2 were able to enter and work immediately upon accession in 2014. After seven years the doors opened fully for families and nonworkers to come. With the gates flung open, millions walked through. Lots of people in the UK were not pleased.

It is fair to say that the numbers of East Europeans, and especially Poles, that came far exceeded expectations. A report for the UK Home Office in 2003 had forecast that “net immigration from the AC-10 to the UK after the current enlargement of the EU will be relatively small, at between 5,000 and 13,000 immigrants per year up to 2010.”23 This was principally because of the low migration rates of the past. Another one the experts got wrong.

The UK Department of Work and Pensions reports the number of people who registered for a National Insurance Number (NINO), which is equivalent to a Social Security number in the United States for both the A8 and the A2.24 Starting from 2004 Q1 through 2018 Q3, 2.7 million individuals from the A8 had registered. There have been a further 900,000 registrations from Bulgaria and Romania registering between 2014 Q1 and 2018 Q3. The 2003 Home Office report seriously underestimated the size of the flow.

Part of the reason for the massive flow of immigrants into the UK was that no other major country such as Germany or France opened its borders; in addition, many of the highly educated Poles spoke English, which made the UK especially attractive. Statistics Poland (2016) reported, based on a survey conducted in 2011–12, that English is the most popular foreign language among those in the 16–65 age group, spoken at various levels of competence by over a third of adult Poles (37%). In contrast, in the United States, according to the Census Bureau, the percentage of the nation’s population age 5 and older that speaks a language other than English at home was 21.6 percent in 2016.25

The problem for the authorities is that they had no means of knowing how many of these East Europeans, who are mostly Poles, were living and working in the UK at any one time. The UK Passenger Survey counts people at arrivals halls but doesn’t count them in departure halls. It asks them if they plan to stay in the UK for at least a year. Many of the East Europeans are coming, at least initially, for short spells.26 In a single year, they often make multiple visits of varying durations. I recall Mervyn King one time at a meeting stressing how many people had come to the UK because of the number of flights from Warsaw and buses that were arriving at Victoria coach station. I piped up that I was surprised at how many flights there also were to Warsaw from UK airports and how many buses from Victoria coach station. The East Europeans were more like commuters than migrants, given that they could come to the UK a number of times of differing durations in a single year. Hence, it is almost impossible to know how many of these commuters are in the UK at any one time.

Return migration in the UK is not a new phenomenon. Dustmann and Weiss (2007) explored this issue empirically before the influx from Eastern Europe using data from the LFS from 1992 to 2004. The authors found that, taking the population of immigrants who were still in the country one year after arrival as the base, about 40 percent of all men and 55 percent of all women had left Britain five years later. Their data suggest that return migration is particularly pronounced for the group of immigrants from the EU, the Americas, and Australia/New Zealand; it was much less pronounced for immigrants from the Indian Subcontinent and from Africa.

The phenomenon of returning is not unique to the Poles in the UK. LaLonde and Topel (1997) found that 4.8 million of the 15.7 million immigrants to the United States who arrived between 1907 and 1957 had departed by the latter year. Chiswick and Hatton (2003) pointed out that return migration exceeded immigration to the United States during the 1930s.

I have another piece of evidence on the economics of walking about as it relates to immigration from a visit I made to a Scottish hotel. The owner told me that they were having a terrible time hiring Scots in their Scottish-themed hotels. In consequence, he had hired lots of Poles, who worked hard and looked great in kilts. He also told me an amusing story that may or may not be true. He said that now many of the records in the Scottish Highland Games were held by very large Poles who didn’t look that great in kilts. They had solved the problem that the record books were full of names like Kacz-kowski and Macherzynski. He had seen the WWF on TV and had come up with a fiendish plan. Andrzej Macherzynski was renamed McTavish, Jacenty Kaczkowski was called David Bell, and so on. Brilliant! Those competing in the Scottish hammer throw, the sheaf toss, the Maide Leisg (look it up!), and the caber toss especially were instructed to stay mum throughout or they would give the game away. Hopefully it was true!

I also gathered from a variety of factory visits when I was on the MPC that employers hugely valued their East European workers: they were never late, would work on weekends and until the job was done, were enthusiastic, and were highly productive. Employers liked their East European workers because of the enhanced flexibility they brought.

Helen Lawton and I (2010) looked at data from several Eurobarometers (2004–7) as well as the 2005 Work Orientation module of the ISSP to examine the attitudes of residents of these A8 countries. Eastern Europeans reported that they were unhappy with their lives and the country they lived in, they were dissatisfied with their jobs, and they experienced difficulties finding a good new job or keeping their existing job. Relatively high proportions expressed a desire to move abroad. We concluded that the UK is an attractive place for Eastern Europeans to live and work. We argued that “rather than dissipate, flows of Eastern European workers to the UK could remain strong well into the future” (2010, 181). That was a good call.

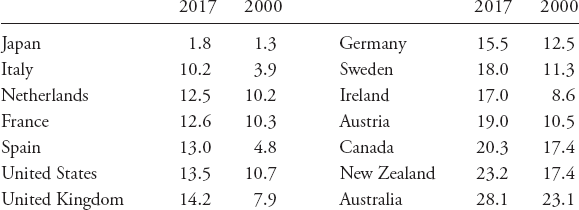

The proportion of the population that is foreign born has risen significantly in all of the main OECD countries. The data below for 2000 are taken from the OECD’s “International Migration Outlook, 2016” (table 1.14) and for 2017 from the “International Migration Outlook, 2018,” which show the change in the proportion of the population that was foreign born in 2017 compared with 2000, ranked from lowest to highest by the 2017 share (data are only available for 2015 for Japan). Japan has the lowest proportion and the Australasian countries, the highest. In all of these major countries the proportion rose, and it more than doubled in Italy, Spain, and Ireland.

With so many workers leaving Poland, that generated a labor shortage and hence a rise in immigration there, too, to fill the gaps, mostly from Ukraine. Recent data from the central statistics office for Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny) on foreign work visas issued in 2017 show the number of work permits for foreigners in Poland grew in 2017, with more than 235,600 issued.27 This is a near doubling (84%) from 2016, and a 258% increase from 2015. Ukrainians in 2017 received 81.7% of all work visas issued in Poland.

The (Small) Impact of Immigration on Jobs and Wages: Fact versus Opinion

There are widespread concerns among the public that immigrants impact wages and jobs. The academic literature says otherwise. A recent major study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017) found that when measured over a period of more than ten years, the impact of immigration on the wages of natives overall is very small. Prior immigrants—who are often the closest substitutes for new immigrants—are most likely to experience wage impacts, followed by native-born high school dropouts, who share job qualifications similar to those of the large share of low-skilled workers among immigrants to the United States.

The study concluded that the literature on employment impacts finds little evidence that immigration significantly affects the overall employment levels of native-born workers. However, they noted, recent research shows that immigration reduces the number of hours worked by native teens (but not their employment rate). Moreover, as with wage impacts, there is some evidence that recent immigrants reduce the employment rate of prior immigrants, suggesting a higher degree of substitutability between new and prior immigrants than between new immigrants and natives.

The study also reported that immigrants influence the rate of innovation in the economy, which, they argued, potentially affects long-run economic growth (2017, 268). Immigrants, it seems, are more innovative than natives; more specifically, high-skilled immigrants raise the rate of patenting per capita, which is likely to boost productivity and per capita economic growth. Immigrants appear to innovate more than natives not because of greater inherent ability but due to their concentration in science and engineering fields.

The OECD (2016a) has rightly argued that there is a certain disconnect between the results of empirical research that studies the impact of immigration at the national level and the publicly perceived impact. Where the former generally find little impact in key areas such as the labor market, the infrastructure, or the public purse—be it positive or negative—in many countries, the public in general assume a negative impact.

As Jonathan Portes notes (2017), the consensus in the economic literature is that negative impacts of migration for native workers are, if they exist at all, relatively small and short-lived. Studies have generally failed to find any significant association between migration flows and changes in employment or unemployment for natives. Since 2014, Portes points out, the continued buoyant performance of the UK labor market has further reinforced this consensus. Rapid falls in unemployment have been combined with sustained high levels of immigration.

The OECD (2016b) further examined the literature on both wages and employment and provides a useful summary of the immigration impacts across countries. The impact on natives’ wages from a 1-percentage-point rise in the immigrant share of the labor force tends to be insignificant, while some studies find small effects (both negative and positive, depending on the study). A review of 18 comparable empirical studies found that with a 1-percentage-point increase in the proportion of immigrants in the workforce, local wages fall just 0.12 percent.28 The OECD notes that since migrants often only constitute a relatively small part of the population, this would imply an almost negligible fall in wages.

The OECD (2016b) notes that once again most studies tend to find no or only a small negative impact on the employment rate: “The majority of empirical studies on the labour market impact of migration look at the aggregate or average local impact, rather than on concrete case studies. Most of these studies find no effect of immigration on local wages nor on employment, while a minority find a small effect, either negative or positive. This is due to a number of reasons. First, migrants’ skills often complement those of the native-born. Second, some native-born residents move up the occupational ladder in response to new foreign-born arrivals. Third, some previous residents move to other areas in reaction to new inflows. Fourth, any local impact is likely to be diluted by adjustment processes, for example changes in the industrial composition and production technologies as well as capital flows” (109).29

A recent meta-analysis updated the list of papers estimating the effect of immigration on wages.30 Of the 28 countries and studies reviewed, 13 find no significant effect, 7 find a small positive effect, and 8 find a small negative effect. A similar meta-analysis for employment has shown that a 1-percentage-point increase in the share of immigrants has an almost negligible impact on native employment, reducing it by 0.024 percent.31 Overall, only about half of studies found a downward effect on wages or employment that is statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

A report by Wadsworth and colleagues (2016) from the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics revealed the impact of EU immigration in the UK prior to Brexit. Their main findings were that EU immigrants are more educated, younger, more likely to be working, and less likely to claim benefits than the UK born. About 44 percent have some form of higher education compared with only 23 percent of the UK born. About a third of EU immigrants live in London.

Areas of the UK with large increases in EU immigration did not suffer greater declines in the number of available jobs or in the wages of UK-born workers. The big falls in wages after 2008 are due to the global financial crisis and a weak economic recovery, not immigration. Changes in wages and joblessness for less-educated UK-born workers show little correlation with changes in EU immigration. EU immigrants pay more in taxes than they take out in welfare and the use of public services. They therefore help reduce the budget deficit.

A 2015 analysis looked at the impact of migration on economic growth for twenty-two OECD countries between 1986 and 2006.32 The results showed a positive impact of migrants’ human capital on GDP per capita; in addition, a permanent increase in migration flows has a positive effect on productivity growth. It seems highly likely that Brexit and the end of free movement will result in a large decrease in immigration flows from European Economic Area countries to the UK.33

It also seems that the presence of a larger number of immigrants lowers prices. Immigrant nannies lower the price of childcare. One of the members of the MPC that I was on had a Latvian “ironer” to iron his clothes. Food prices in the UK are lower because of the presence of Poles, and in Los Angeles and in many other U.S. cities lawn services, house-cleaning services, and car washes are less expensive because of the presence of illegal immigrants.

Saul Lach (2007) examined the behavior of prices following the unexpected arrival of a large number of immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU) to Israel in 1990. He used store-level price data on 915 consumer price index products to show that the increase in aggregate demand prompted by the arrival of the FSU immigrants significantly reduced prices during 1990. Lach found that a 1-percentage-point increase in the ratio of immigrants to natives in a city decreased prices by 0.5 percentage points on average. Natives like lower prices.

Public perception of crime in the United States often doesn’t align with the data. Opinion surveys regularly find Americans believe the crime rate is up. In twenty-three Gallup surveys conducted since 1989 a majority always said there was more crime in the United States compared with the year before. In every year since 2005 over 60 percent said there was more crime than a year earlier.34 In a Pew Research Center survey in late 2016, 57 percent of registered voters said they thought the crime rate had worsened since 2008, 27 percent said it was the same, and 15 percent said it had improved, even though violent and property crime had fallen by double digits.35 Interestingly, there is no indication in the data that respondents see any change in the likelihood of them personally experiencing crime.

According to Gallup there has been little change at all over time in the percentage of people in the United States who frequently or occasionally worry about their home being burglarized when they are not at home (44 percent in 2004 versus 41 percent in 2014–17).36 Over these years there was a big decline in the proportion thinking they would be a victim of terrorism, down from 41 percent in 2001–4; 37 percent in 2005–8; 31 percent in 2009–13; and 30 percent in 2004–17. In an Ipsos Mori Public Perceptions poll taken in the fall of 2017, around eight in ten Americans thought the murder rate had risen (52%) since 2000 or was about the same (26%).37 The rate has declined by 11 percent. Americans think one in three people in U.S. jails and prisons was born in a foreign country. In fact, only one in twenty is an immigrant.

Perhaps surprisingly, a majority of the studies in the United States have found lower crime rates among immigrants than among non-immigrants, and that higher concentrations of immigrants are associated with lower crime rates. Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partly explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate. Wadsworth (2010), for example, found that cities with the largest increases in immigration between 1990 and 2000 experienced the largest decreases in homicide and robbery during the same time period.

A study by Ewing and colleagues (2015) at the American Immigration Council noted that while the illegal immigrant population in the United States more than tripled between 1990 and 2013 to more than 11.2 million, “FBI data indicate that the violent crime rate declined 48%—which included falling rates of aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder. Likewise, the property crime rate fell 41%, including declining rates of motor vehicle theft, larceny/robbery, and burglary.” They also found from an analysis of data from the 2010 American Community Survey that roughly 1.6 percent of immigrant men aged 18–39 were incarcerated, compared to 3.3 percent of the native born.

Views on Immigration: Nations Divided

According to Ford and Goodwin, the left-behinds in the UK are strongly opposed to political and social developments they see as threatening sovereignty, continuity, and identity.

Anxieties about immigration and its effects, demands for reductions in the number of immigrants, and the belief that immigration poses a serious problem to the nation are all expressed most strongly by the left behind coalition of older, less skilled and white workers.

They went on.

Already disillusioned by the economic shifts that left them lagging behind other groups in society, these voters now feel their concerns about immigration and threats to national identity have been ignored or stigmatized as expressions of prejudice by an established political class that appears more sensitive to protecting migrant newcomers and ethnic minorities than listening to the concerns of economically struggling white Britons. (2014, 126)

Ford and Goodwin’s comments seem to apply equally well to the left-behinds in other countries such as the United States, France, and Austria.

Most U.S. voters view immigrants positively, but most Trump voters don’t.38 Overall the United States is supportive of immigration and that support if anything has increased slightly over time. Gallup has regularly asked, “Thinking now about immigrants, that is, people who come from other countries to live here in the United States: In your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?” In its June 2018 poll, 29 percent (50%) said decreased, 39 percent (32%) said stay at the present level, and 28 percent (14%) said increased; the numbers in parentheses are those from a survey taken in July 2009. Similarly, when asked in these surveys, “On the whole, do you think immigration is a good thing or a bad thing for this country today?” in June 2018, 75 percent said immigration was a “good thing” versus 57 percent in July 2011.39 So opinion is moving in favor of immigration in the United States.

One of the starkest divides in the United States between Trump and Clinton voters was their attitude toward immigration. A Pew poll taken between August 9 and 16, 2016, asked respondents for their views on undocumented immigrants.40 Here Republican is defined to include Republican leaning, with the same holding true for Democrats, and I report below the percentage who answered yes to the following questions about immigrants and immigration.

Republican |

Democrat |

|

Mostly fill jobs U.S. citizens do not want? |

63 |

79 |

As hard-working as U.S. citizens? |

65 |

87 |

No more likely than U.S. citizens to commit serious crime? |

52 |

80 |

Should the U.S. build a wall along entire Mexican border? |

63 |

14 |

According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted just before Election Day on October 25–November 8, about eight in ten Trump supporters who cast ballots or were planning to (79%) said illegal immigration was a “very big” problem in the United States.41 (Twenty percent of Clinton voters responded affirmatively to the same question.) Even more Trump supporters (86%) said the immigration situation in the United States had “gotten worse” since 2008. In the same Pew survey, voters were asked whether they thought particular issues were a “very big problem” in the United States. The chart below lists the percentages of those who responded affirmatively.

Clinton supporters |

Trump supporters |

|

Illegal immigration |

20 |

79 |

Terrorism |

42 |

74 |

Job opportunities for working-class Americans |

45 |

63 |

Crime |

38 |

55 |

Job opportunities for all Americans |

43 |

58 |

Conditions of roads, bridges, infrastructure |

46 |

36 |

Affordability of a college education |

66 |

38 |

Racism |

53 |

21 |

Gap between rich and poor |

72 |

33 |

Gun violence |

73 |

31 |

Climate change |

66 |

14 |

A CBS News poll taken in March 2018 asked registered voters, “Do you favor or oppose building a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to try to stop illegal immigration?” Overall, 60 percent opposed and 38 percent favored. Republicans favored 77 to 20, while Democrats opposed 10 to 88, with independents opposing 36 to 61.42

A Pew poll finds that overall most Americans think immigrants strengthen the country and have a positive view of the contributions of immigrants to the country.43 About two-thirds (65%) say that immigrants “strengthen the country with their hard work and talents,” while 26 percent say that immigrants are a burden because they take jobs, housing, and health care away from native-born Americans. Positive views of immigrants, Pew found, have continued to increase in recent years. Attitudes today are the reverse of what they were in 1994. At that time, 63 percent said immigrants did more to burden the country, while just 31 percent said they did more to strengthen the country. As recently as 2011, about as many said immigrants burdened (44%) as strengthened (45%) the country. Majorities of those across levels of educational attainment take a positive view of immigrants’ contributions to the country. However, views are the most positive among those with the highest levels of education. For example, four-fifths of postgraduates say immigrants strengthen the country, compared with three-fifths of those with no college experience. Adults ages 18–29 overwhelmingly say immigrants do more to strengthen than burden the country. Views also are broadly positive among those ages 30–49. Views among those 50 and older also tilt positive but by smaller margins.

A 2017 PRRI Report found that fears of immigration and cultural displacement were more powerful factors than economic concerns in explaining why white working-class voters went for Trump. Cultural anxiety mattered more than economic anxiety. This was based on surveys conducted before and after the 2016 election. Cox and coauthors (2017) found that nearly two-thirds of respondents thought that American culture and the American way of life had deteriorated since the 1950s. White working-class voters who said they felt “like a stranger in their own land” and believed that the United States needs protecting against foreign influence—the culturally displaced—were 3.5 times more likely to vote for Trump. White working-class voters who favored deporting immigrants living in the country illegally were 3.3 times more likely to have voted for Trump. More than six in ten thought the growing number of immigrants in America threatened American culture. For many of the left-behinds, this was a culture war.

The American National Election Studies (ANES) pre- and post-election survey of over 4,000 respondents found that racial attitudes toward blacks and immigration were the key factors associated with support for Trump in 2016.44 The results indicate a probability of Trump support higher than 60 percent for an otherwise typical white voter who scores at the highest levels on either the anti-black racial resentment or the anti-black influence animosity scale McElwee and McDaniel constructed. This compares to a less than 30 percent chance for a typical white voter with below-average scores on either of the two measures of anti-black attitudes. The effect of immigration attitudes for white people was even stronger than anti-black attitudes. The results predict an approximately 80 percent probability of voting for Trump for an otherwise average white person with the most anti-immigrant attitudes, compared to less than 20 percent for a white person with the most pro-immigrant attitudes.

In the spring of 2018 President Trump introduced a zero-tolerance immigration policy that resulted in over 2,000 children being separated from their parents. After huge public outcry the program was reversed, not least because the majority of Americans were against the separations.45 However, Republicans were more likely to support the policy. A Quinnipiac poll found that 66 percent of U.S. voters opposed taking the kids. In contrast, 55 percent of Republicans voters supported separating children from their immigrant parents. Ipsos and YouGov with the Economist found comparable results.46

Interestingly, at the same time a larger share of people at any point since 2001 said immigration is good for the nation. According to a Gallup poll taken in the first two weeks in June 2018, 75 percent of Americans said immigration in general is good, compared with 65 percent of Republicans.47 Support for reining in immigration is now at its lowest level in more than half a century. A Pew Research poll taken in June 2018 found that immigration in the United States had emerged as the most important problem facing the nation.48 In January 2017 immigration was cited less often as being an important problem facing the nation than health care, the economy, unemployment, race relations, and then president-elect Donald J. Trump.

In Las Vegas in June 2018 President Trump said about immigration, “I like the issue for [the] election.” He went on. “Our issue is strong borders, no crime. Their issue is open borders, get MS-13 all over our country…. We need people to come in, but they have to be people that love this country, can love our country, and can really help us to make America great again.”49

Being mean to immigrants has consequences; they leave. Donato Paolo Mancini and Jason Douglas in the Wall Street Journal have reported on an exodus of European workers from the UK, especially in the health-care field.50 They filed an FOI request with the UK’s General Medical Council and obtained data showing the number of specialized doctors with non-UK EU citizenship has reached an eight-year low of 10,487 in 2018, down from a peak of over 12,000 in 2014. The article also reported that widespread knowledge of English, the easy mutual recognition of qualifications, relatively good salaries, and world-class research had acted as magnets for doctors. But now, as a Brexit threatens, top doctors are quitting. They reported that the National Health Service had a personnel shortage just shy of 110,000 in the first six months of 2018, 11,500 of which were doctor positions. Down we all go.

Recessions and long periods of semi-slump have consequences, and there will inevitably be scapegoats. Perceptions and reality on the impact of immigration remain far apart across the political spectrum. Pity the poor immigrant these days, legal or illegal.