THOSE LITTLE SPARKS ARE WORTH MONEY!

Because this is a book about innovation, and the word itself has been used and overused by every business consultant on the planet, let’s begin by agreeing on a definition. You may have your own, which is fine. This is not a one-size-fits-all book. The only goal is to encourage you to think and challenge yourself.

Let’s define innovation as:

The creation of new value that serves your organization’s mission and customer.

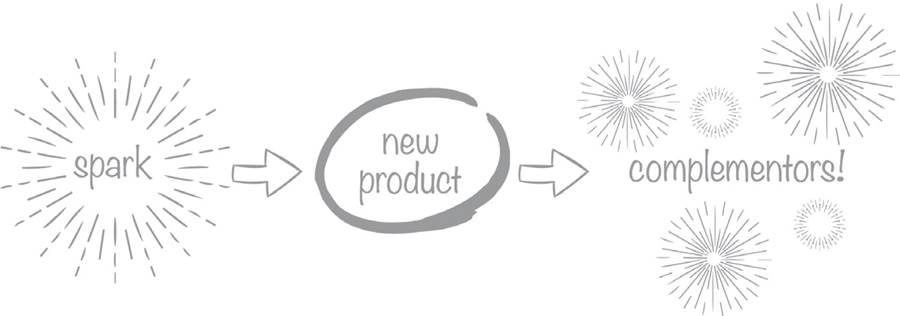

Innovation begins with the spark of any new idea or process from anywhere—the scientist in the laboratory, the marketing manager, the techie in IT, the assembly line worker, the maid who cleans the hotel rooms. This new idea or process—large or small, planned or a lucky accident—is then evaluated against a simple standard: Will it add value, help us fulfill our mission, and serve our customer?

Can it . . .

• Increase sales and profits?

• Expand our market?

• Deliver more value to our customers?

• Raise the productivity of our employees?

• Reduce our operating expenses?

• Position us as industry leaders?

If the answer is yes to any of the above questions, the idea is worthy of serious consideration. The spark should be given oxygen, developed, and put to the test.

If the answer is no to all the questions, the little spark should be left to fizzle out. (It sounds cruel, but business is a tough world where you make hard choices.)

It’s that simple!

DON’T BE A ONE-HIT WONDER

Too often, we’ve seen a company make a spectacular innovative breakthrough, ride the wave of success for a year or two, and then go bankrupt or get sold for pennies on the dollar. These companies are one-hit wonders. They don’t understand the Innovation Mandate. If it’s your goal to make a few quick bucks by going this route, this book isn’t for you. Please give it to a friend.

On the other hand, if you’re a leader who wants to build a successful business that stays on top year after year, then read on!

All across the globe, the Innovation Mandate is taking hold. Innovation can be big and exciting or incremental and subtle. It can be accomplished by people at all levels, from a dedicated research and development technician who invents a new product to a marketing manager who figures out a new way to leverage social media.

Consistent innovation is not merely a good thing or a useful thing. In today’s time of massive market disruption, intensifying global competition, and rapid technological and social change, an organizational commitment to innovation is a requirement. Companies that innovate day after day are dominating their markets. Those that take a haphazard or one-hit-wonder approach to innovation are being vanquished by their rivals.

The companies that stay on top—like Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook—are relentless innovators. The ones that either perish or fall from the top—Blockbuster, Eastman Kodak, Polaroid, Borders Group—have one thing in common: a failure to consistently innovate, year after year. It’s true that the ones who disappeared all had their moments in the sun. At one time or another, all of them were known for their astonishing innovations. (If you’re old enough to remember the first time you could walk into a store and rent a VHS cassette of a new feature film and take it home and watch it—that was truly revolutionary!) But they got fat and lazy. They failed to grasp the Innovation Mandate. Soon thereafter, death came knocking.

While many leaders know the critical importance of innovation, they forget that recognition needs to be followed by consistent, organized action. As a survey of CEOs by Harris Interactive reported, “Forty-seven percent report that their company has no team, process, or system for vetting new ideas in order to decide which ones to invest in. Moreover, only a minority report that their company promotes enterprise innovation by providing funding or access to educational or idea-sharing forums, and only one in three report that they have a team specifically dedicated to brainstorming new ideas.”1

Many top companies understand that when it comes to sparks of innovation, quantity equals quality. As a 2017 MIT Sloan study entitled “Profit Growth Is Correlated With More Accepted Ideas” reported, “Looking at 28 companies using ideation management software over two years, the authors found that the greatest number of ideas per 1,000 users correlated strongly with a company’s profitability and growth.”2

It’s a simple formula:

Who could argue with that?

WE WERE BORN TO INNOVATE

For too long, consistent innovation has been seen as a mysterious process. Many call it the secret black box, and it’s what some consultants and business gurus try to sell you. It’s based on the idea that an innovation system has to be like the Manhattan Project: top secret, accessible to only a few super brains, and expensive. They want you to believe that only the secret black box can deliver a steady flow of sparks.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The reality is this: unless you are truly allergic to anything “outside the box,” you and everyone in your organization are innovators.

When you figure out how to unjam the copier by using a paper clip, you’re an innovator.

When you bundle two products together at a special price, you’re an innovator.

When you enter into a partnership with another company to share a common resource, you’re an innovator.

When you see a need in the marketplace and design a product or service to satisfy it, you’re an innovator.

The spark of innovation simply means a new idea becomes reality.

We too often think about innovation in a narrow sense, as a massive breakthrough that is going to change the world. It’s like how Steve Jobs put it: he wanted to “put a ding in the universe.”3 But for those of us who are not likely to ding the universe, we can still have a major impact in all areas of our life and the organizations we serve.

Human beings are born innovators. From the day we take our first steps to the day we shuffle off to the retirement home, we’re constantly trying to find new and better ways of doing things. We invent gadgets, find shortcuts, solve problems, look at things in new ways. This is how the world progresses! Every artifact of modern civilization that we take for granted was once a startling new innovation.

The key to the Innovation Mandate is to keep those sparks coming—and to know how to capture them.

THEY DO IT, AND YOU CAN TOO

Sometimes innovations happen because of a deliberate effort. But new sparks often emerge quite by accident and are luckily recognized as innovations, and savvy businesspeople exploit their incredible potential.

Innovation doesn’t only happen in Brooklyn or Silicon Valley. All across America, low-profile, bread-and-butter companies produce consistent innovations that make you sit up and take notice. Here are just a few examples:

• A leading manufacturer of high-quality power tools, Dewalt has created an award-winning insight community of more than ten thousand end users. The company calls it “user-driven innovation,” in which direct user feedback inspires the company’s engineers to redefine what’s possible. By connecting with its customer community to get to know what they need while gathering product, packaging, and marketing feedback, Dewalt generates priceless data on what it’s doing right, what it’s doing wrong, and where it should go in the future.4

Your organization could likely benefit from a sustained and close connection with a community of people who test your products or services! You can have one too—all you need to do is reach out to them and listen to what they say.

• DHL, the world’s largest express logistics services company, welcomes customer ideas during hands-on workshops in Singapore and Germany. Members of the DHL customer community have participated in thousands of engagements to suggest solutions to improve package delivery service.

One of the many inventions that originated from a workshop is the Parcelcopter. In development since 2013—well before the Amazon Prime Air drone delivery system—it has evolved into an automated tiltwing aircraft that delivers packages to recipients’ doorsteps, with minimal human intervention. Anyone within the service area can bring a package to one of DHL’s “Parcelcopter Skyports,” and the drone will carry it up to eight kilometers over mountainous terrain.5 Markus Kückelhaus, vice president of innovation and trend research at DHL, told analysts, “Artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and automation are driving intelligent supply chains and transforming the future of the global logistics industry.”6

It’s a good example of how customers can collaborate with a company’s internal innovators to conceive, build, and test a startling innovation. And by the way, DHL has a vice president of innovation and trend research! He’s their innovation champion, which we’ll talk about later in the book.

• British Airways is saving £600,000 a year in fuel costs by descaling the toilet pipes on its planes, thus making the aircraft lighter. The idea came from an online suggestion box created for BA staff. Other cost-saving ideas from employees have been to replace glass wine bottles with plastic ones, build lighter catering trolleys and cargo containers, wash engines more regularly, reduce the volume of water tanks, and deploy lighter cutlery for business-class passenger meals. The benefits? A significant reduction in the weight of each aircraft, which translates to lower fuel costs, the number one expense of any airline.7

Employees are a rich source of new ideas! All you need to do is set up your innovation pipeline (more about that later in the book) and keep it full.

• Okay, here’s one from Silicon Valley. Originally called the “awesome button,” the Facebook “like” button was first prototyped in one of Facebook’s infamous hackathons, where employees are gathered together and given free rein to explore possibilities. But founder and top dog Mark Zuckerberg repeatedly rejected the idea, saying it would encourage “low-value” interactions. Eventually, Facebook engineers called it the “cursed project” that would never make it past a skeptical Zuckerberg. But advocates persisted until data scientist Itamar Rosenn provided data showing that a like button actually increased the number of comments on a post. Zuckerberg gave the green light, and it’s been a huge hit with Facebook users, adding to the company’s burgeoning bottom line.8

This shows that many innovations are not embraced immediately; they often need more time to develop, and they eventually succeed because one or more people are true believers.

You don’t need an advanced degree to capture innovation and reap its profits. You never know where the spark of innovation is going to come from—or from whom.

Consider Cassidy Goldstein, who at age eleven invented a device for holding broken crayons together. In 2006, the Intellectual Property Owners Education Foundation named Goldstein “Youth Inventor of the Year.”9

Or George Weiss, who at age eighty-four invented a digital game app called Dabble—The Fast Thinking Word Game, which is available for iPhone, iPod Touch, and iPad.10

These—and millions of other innovators—are ordinary people who may be working in your company right now.

You could fill a book with examples like these—but you get the point. New ideas can come from anywhere, and implementing them is often an easy process that reaps great rewards.

THE MORE YOU DO IT, THE BETTER IT GETS

Innovation is like any other skill: the more you do it, the better it gets. If you stick with it and don’t lose your focus, soon everyone on your team or in your organization—whether they number in the tens or the thousands—will see themselves as innovators, will be engaged in the ongoing process of innovation, and will want to contribute more to the success of the organization.

Managers at Toyota, where everything is measured, track the number of employee suggestions made during the year. Over a thirty-five-year period, Toyota’s culture of innovation has increased the number of annual suggestions from one per ten employees to four hundred and eighty per ten employees. That’s a huge increase, and it’s because the company culture has instilled in every employee the value and necessity of new ideas. And these aren’t ideas that have come from an expensive R&D program, although Toyota has that too. These are “free” ideas that cost the company nothing to obtain!11

How can any leader say no to that?

IT’S A TEAM EFFORT

Innovation works best as a team effort, with stakeholders from across the business having a clear and crisp understanding of what it is, its goals, and its benefits. This requires that innovation be discussed in a normal human language that everyone can understand and act upon. By creating an innovation strategy, you’ll take the complexity of innovation and make it actionable and real across the entire enterprise. By following it and creating an organizational mandate to innovate, you’ll unleash the profit power of new ideas and harness their tremendous energy to move the organization forward.

BEYOND THE BRIGHT, SHINY OBJECT: THE WIDE SPECTRUM OF INNOVATION

Many people think about an innovation being only a technology or product or some other bright, shiny object. This is one area that creates a great deal of confusion because the overwhelming majority of business leaders believe that innovation lives only in research and development. In his book, Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs, Larry Keeley does an exceptional job of describing in practical terms how different types of innovations work across an enterprise.12

However, since the value proposition of this book is to help you stay focused on a crisp, clear, and easy-to-deploy way forward, let’s look at the types of innovation from the perspective of our simple definition. As previously mentioned, innovation is:

The creation of new value that serves your organization’s mission and customer.

The key word is “new,” which has two different meanings.

It can mean “new to the world,” such as an invention or process that has never been seen before. When it was introduced, the Apple iPod was a new invention. Uber was a new business model. The idea of implanting GPS devices in materials moving through a supply chain was a new process.

It can also mean “new to your organization.” Taking a method or process from some other industry and applying it to your own is an innovation. For example, in recent years, automakers have been taking computers and putting them in automobiles to serve a wide variety of functions, from engine diagnosis to communications and security. The carmakers didn’t invent computers, but they’re finding ways of creating innovative uses for them.

On a practical level, innovation falls across a nearly infinite spectrum of functional areas. This can include but is certainly not limited to:

• How you invent better experiences across each touchpoint for your customers

• Channeling innovations that help you deliver your customer value faster and better

• New business process innovations that help you meet your specific strategic goals

• Products and technologies that you sell to your customers

• The way in which your team collaborates and cocreates

• The way in which you communicate your value to the marketplace

• How you measure and monitor your organizational progress

• Anything that helps your organization either save money or make money!

Studies show that the most profitable organizations in the world embrace the Innovation Mandate. They’re dedicated to innovation as a core competency, and the best leaders “walk the walk” and completely commit to innovation as an organizational priority. Studies also show that consistent innovation—in all its forms—drives profitability and organizational growth and competitiveness, and that innovation is the new enterprise priority.

In your company, the spark of innovation exists right now. All you need to do is tap into it.

THE FOUR LEVELS OF INNOVATION ON THE RISK-REWARD SCALE

Every investor knows there’s a direct correlation between risk and reward.

The greater the risk, the greater the reward.

The lower the risk, the lower the reward.

Savvy investors put their money on a mix of opportunities that present a range of risk vs. reward. They want some low-risk, low-reward opportunities that provide incremental returns, while also taking high-risk positions that may provide breakthrough or even disruptive returns.

They also must refrain from being tempted by empty innovation, which at any level of risk brings little or no return.

Innovation is no different from any other investment. The spectrum of risk and reward is wide and proportional. Leaders and innovation champions need to recognize and avoid empty solutions while championing and exploiting the next three levels of true innovation.

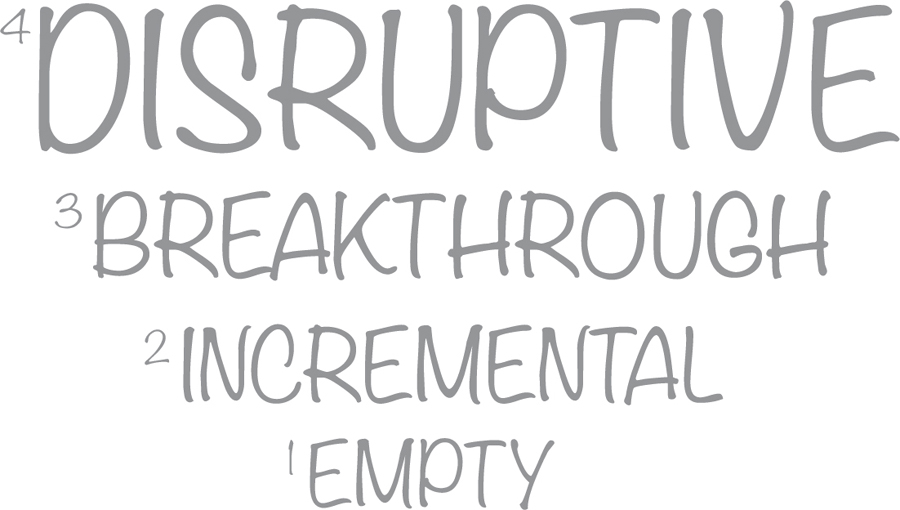

1. Empty

An empty innovation is something different or new that adds little value in the mind of the customer. It may even turn out to be an expensive mistake. If a spark is nothing more than an empty innovation, let it fizzle out.

A notorious empty innovation that refuses to die are those “paddle shifters” mounted on the steering wheels of cars with automatic transmissions. That’s right—on a car with an automatic transmission, you can override the “automatic” part and shift gears with your fingertips on the steering wheel. It’s supposed to give you the illusion of shifting manually. The problem is, 99.9 percent of car buyers don’t care about paddle shifters. As Nick Richards, the product development communications manager for General Motors, told the New York Times, “Our research shows that customers with paddles use them rarely, with more than 62 percent saying they use them less than twice a year. When customers do use them, 55 percent say that it is for sporty driving situations.”13

The Times went to a Subaru dealership in Queens and asked a shopper what she thought of the paddle shifters on the truck she was looking at. “A what?” she said. “I have no idea what those things are. I just drive the car.”14

Paddle shifters are useful on Ferrari Formula One racing cars, for which they were developed. But for the average driver, they’re a complete waste of money.

One of the rules of innovation is this: just because you can do something new doesn’t mean you have to. Every spark needs to be evaluated with a critical eye toward its real-life value to your customers. We’ll talk much more about that in the pages ahead.

2. Incremental

These are the innovations that are at the heart of “the Toyota Way” of kaizen, or “continuous improvement.” One incremental innovation alone may not make a big difference in your sales or your business. But a sustained organizational transformation to become an innovation leader, during which, for example, you make one small innovation every day for a year, can add up to real value. In an interview with Harvard Business Review, Katsuaki Watanabe of Toyota said, “There is no genius in our company. We just do whatever we believe is right, trying every day to improve every little bit and piece. But when seventy years of very small improvements accumulate, they become a revolution.”15

It’s important to remember that incremental innovations need not be visible to the consumer! They’re often hidden from view in the supply chain. For example, consider how UPS keeps developing new ways to shave seconds off the time it takes for the driver to deliver a package. Jack Levis, UPS’s director of process management, told NPR that “one minute per driver per day over the course of a year adds up to $14.5 million.”16

• In the United States, UPS drivers make as few left turns as possible. Why? Results of complex mathematical calculations have shown that when plotting a delivery route, it’s slightly faster to make right turns to get where you want to go than sit at the light waiting for a left turn.17

• To save time, drivers are taught how to start the truck with one hand while buckling up with the other.

• Slip-and-fall accidents cause pain, cost money, and waste time. At the UPS driver training camp, special slip-and-fall simulators are used to teach drivers to walk safely in slick conditions.

• To save fuel costs, the trucks don’t have air-conditioning. In hot weather, drivers work with the door open.18

Consumers are unaware of these incremental innovations. They experience only great service at a low price.

This is the kind of innovation that happens every day, and which over time can make a huge difference to your company. If you keep the small sparks coming, they’ll add up to a big competitive advantage.

3. Breakthrough

These are the big, splashy ideas that can elevate a brand overnight. Something transformative, like Face ID, the facial recognition system on iPhone. Introduced in December 2017, Face ID is a form of biometric authentication. Rather than a password or authentication app, biometrics are something you are. Relying on the unique characteristics of your face, Face ID initially scans your face accurately enough to recognize it later. Then, when you activate it and allow the camera to look at your face, it compares the new scan with the stored one with enough flexibility to recognize you nearly all the time, even in a wide variety of lighting conditions and if you’re wearing sunglasses.19

Clearly, this innovation is more than incremental and is going to add value to the product and help Apple fulfill its mission.

Also, it’s worth noting that many breakthrough innovations are not new ideas. No one at Apple suddenly woke up and said, “Hey, wouldn’t it be cool if our phones had facial recognition?” The idea had been around for decades, and had been done with fingerprint and iris scanning. But Apple made the organizational decision to make this idea a reality. They took the spark and pumped oxygen into it. They made the commitment in resources to get the job done.

Don’t overlook those stubborn sparks that have been smoldering without ever catching fire. Like the Facebook like button or Apple’s Face ID, it often takes time for an idea to fully mature. Your innovation pipeline—which we’ll discuss in the pages ahead—needs to be able to handle good ideas that develop slowly.

4. Disruptive

Some innovations don’t just elevate the company to the top of the market; they fundamentally disrupt and even destroy the market.

In the early twentieth century, the automobile destroyed the horse-drawn carriage industry.

In the 1950s and 1960s, airline travel destroyed both the transatlantic passenger ship industry and the US passenger rail industry.

The mobile phone has disrupted the traditional telephone landline industry. (When was the last time you saw a public pay phone? If you’re young enough, you may never have seen one.)

Netflix destroyed Blockbuster and the traditional movie rental industry.

Online pornography destroyed the print porn industry and adult movie houses.

Uber decimated the traditional taxicab industry.

Amazon destroyed the big chain bookstores and hastened the demise of vulnerable department store chains including Sears, Brookstone, National Stores, Nine West, Claire’s, and Toys “R” Us.20

The thing about disruptive innovations is that you can’t predict them. They’re like wildfires that start small, with just a little spark, and only over time do they eventually become conflagrations. Of course, every entrepreneur—including Jeff Bezos of Amazon—strives to be a disruptor, just like every kid in a rock band strives to be Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones. But few actually become disruptors, and from the outside it’s difficult to predict which ones will ascend to that level.

I guarantee you that right now, as you read this, some little company with a crazy innovation that no one is talking about is working hard and growing; and in five or ten years it will emerge as a massive disruptive force.

THE MANY SOURCES OF INNOVATION

In order to capture and nurture those tiny sparks that eventually explode into life-changing innovations, you have to know the many places where they come from and how to identify them.

Sometimes the pursuit of innovation is deliberate and well funded, while at other times new ideas emerge as accidents during the pursuit of some other goal. Innovation can be carried out in secrecy, or it can be pursued with a public campaign. There are many ways forward—here are the key methods to innovate that you need to know.

1. From the Lab

A carefully planned and funded organizational effort can be designed to achieve a breakthrough. The most obvious examples are the new products developed by pharmaceutical companies. To bring a new drug to market takes a huge investment of time and money. A recent study by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) put the average cost of developing a prescription drug that gains market approval at $2.6 billion. The figure is based on an average out-of-pocket cost of $1.4 billion plus the estimated $1.2 billion in returns that investors don’t get on their money during the decade or so a potential new drug spends in development.21

The study added that an additional $312 million is spent on post-approval development—studies to test dosage strengths, formulations, and new indications—for a life-cycle cost of $2.9 billion.

Another good example of planned innovation was the March 2017 launch of the SpaceX rocket Falcon 9. This event made headlines because it was the first time in history that an orbital rocket had been launched into space, landed itself safely back on Earth (in this case, a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean), was refurbished, and launched again. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk said, “It means you can fly and refly an orbital class booster, which is the most expensive part of the rocket. This is going to be, ultimately, a huge revolution in spaceflight.”22

In this case, the innovation itself was nothing new. People have talked about developing reusable rockets for decades. But SpaceX made a commitment to making it a reality. They set up the lab, funded it, and persisted until they had solved the problem. In the process, they pioneered countless small innovations that, when put together, made a significant breakthrough.

Planned innovations aren’t just big-ticket R&D programs. Toyota’s Creative Idea and Suggestion System (TCISS), which was formally instituted in 1951 and now reportedly draws forty-eight new ideas from each employee every year (of which, according to Chuck Yorke and Norman Bodek’s book, All You Gotta Do Is Ask, nine are adopted), is a form of planned innovation. Toyota has been doing it for so long that the rate of new ideas has become predictable, and while the exact ideas are not known until they’re submitted, the overall idea flow is entirely planned and has been formalized into the company’s operations.23

Whether your Innovation Mandate is a deliberately funded effort or a daily program of solicitation from frontline employees, you want a steady and predictable flow of new ideas for your organization!

2. Accidental Discovery

The second source of innovation includes those fortuitous accidents that occur when you’re trying to solve one problem and you fail—only to discover that you’ve solved an entirely different problem. In industry, many examples have become legendary. The pattern is common: the researcher invents something, and it doesn’t work; but the invention has some other innovative use, which top management sometimes recognizes only much later. One of the most well known is the invention of the Post-it Note. Actually, Post-it Notes, which continue to earn one billion dollars a year in sales, came about after not just one or two, but four unplanned breakthroughs:

1. In 1968, Spencer Silver, a chemist for 3M, accidentally formulated a weak adhesive made of tiny acrylic microspheres, which were nearly indestructible and remained sticky even after several uses.

His bosses at 3M were not interested, and the adhesive languished in the innovation pipeline.

2. In 1972, Art Fry, another 3M chemist and frequent singer in his church choir, had a problem: his paper bookmarks kept falling out of his hymnal. He put Silver’s adhesive on bits of paper, and they stayed in place without damaging the book. He’s credited with inventing the first Post-it Note.

Again, there was no interest from the bosses at 3M, and the idea was still not developed at that time.

3. A laboratory manager named Geoff Nicholson believed in the idea. Nicholson decided that if 3M’s marketing department wouldn’t launch the product, then his lab team would market it themselves. In 1977, the product was test marketed under the name “Press ‘n Peel.”

Sales were poor, and with a yawn the bosses again said no.

4. In 1978, Nicholson handed out free samples to residents of Boise, Idaho, and 90 percent of the recipients said they wanted more of the sticky notes. Finally, on April 6, 1980—twelve years after Spencer Silver’s original breakthrough—the product emerged from the innovation pipeline and debuted in US stores as “Post-it Notes.” They were an immediate sensation.24

The hardest innovations to identify and embrace are the ones that no one sees coming. They’re disruptive or they demand that managers discard their preconceptions about what constitutes success.

And above all, when something comes along that’s unfamiliar or risky, the safe response is to say no. There’s an axiom in business that no one ever got fired for not taking a chance. In many organizations, the avoidance of risk is rewarded. Managers are taught to stick to the company playbook, don’t make waves, and reject anything that deviates from the business plan.

In some cases, company leaders are quick to recognize an innovation. In the early 1990s, the drug company Pfizer completed several early trials of sildenafil citrate, but it was not promising as a heart medication. The drug might have been shelved, but male volunteers in the clinical trials reported increased erections several days after taking a dose of the drug. Pfizer, realizing it could have an unintended market disruptor, changed course. In March 1998, the FDA approved the use of the drug Viagra to treat erectile dysfunction. In the following weeks, US pharmacists dispensed more than forty thousand Viagra prescriptions, and the drug became one of the biggest sellers of all time.25

Pfizer avoided a common problem: anchoring bias, a fancy psychological term that describes the tendency for an individual to rely too heavily on an initial piece of information offered (known as the “anchor”) when making decisions. In other words, when sildenafil citrate was shown to be ineffective as a heart medication, anchoring bias could have led Pfizer researchers to shelve the product. But they saw something unexpected and were willing to explore this new information.

3. Collaboration with Partners

An important third source of innovation can be an active collaboration with stakeholder partners. Here are a few examples:

Stakeholder collaboration. A purposeful collaboration among three stakeholders—problem, opportunity, and customer facing—produces a tremendous flow of powerful insights that can result in amazing new innovations.

Some of the methods that help drive the collaborative enterprise include hackathons, the use of enterprise social networks that leverage game mechanics and social engagement, innovation competitions, and targeted ideation sessions.

It’s vital for companies to regard stakeholders as partners in new product or service development. As Technology Innovation Management Review noted, “Over the last two decades, several studies have shown the importance of cocreating innovations with stakeholders. Suppliers, customers, and users have a wide range of knowledge and skills that are needed for innovation development, but which often remain untapped.” Collaboration with stakeholders helps companies learn how to more effectively meet customer requirements while improving performance and development time, and reducing costs.26

Vendor collaboration. Suppliers are often overlooked as a source of innovation. As the Institute for Supply Management noted, the most important reason for involving suppliers early in innovation activities is to provide capabilities not available in-house. The next most important reasons are to reduce time to market, and increase product or service differentiation.

They found that while 90 percent of leading companies have a structured process for collaborating with suppliers, just 54 percent of the average companies have a structured process. The study also revealed that leading companies expect to further rely on collaborative supplier innovation in the future.27

Once suppliers are involved in the development process, procurement takes a seat at the strategy table, going beyond reducing costs and improving efficiencies to the next step: focusing on building value and profits.

Brand collaboration. Organizations are beginning to cocreate with brands from other markets to produce an opportunity for the respective businesses and the customers they serve.

In fact, a new popular term, “COLAB,” that speaks to brands collaborating with each other, is popping up everywhere. As Alison Coleman wrote for Virgin.com, successful brand collaboration depends on both brands being able to benefit from the existing market of the other, or by filling a gap in the market through a collaborative relationship that competitors could not otherwise replicate.

At first glance, brand collaboration can involve some surprising cross-sector alliances, which is part of the appeal. Virgin Atlantic collaborated with the original onesie designers OnePiece to produce a limited edition OnePiece onesie for Virgin’s first-class passengers. This was a blend of two high-profile brands with very different yet mutual consumer interests.28

Is there any brand more old-school than Levi’s, which was founded in 1853? Yet Levi’s and internet giant Google teamed up to enter the wearable technology market. Codenamed Project Jacquard, the Levi’s Commuter-Jacquard by Google partnership manufactured a touch-and-gesture interactive denim jacket designed to allow bicyclists to ride without having to reach for their phones. By lightly tapping or swiping a sleeve on their jacket, the cyclist can access a map or change a song on Spotify, for example, without compromising their safety on the road.29

Customer community collaboration. As we saw with Dewalt and DHL, another great way to get the best innovations for your customers is to cocreate the innovations with them. Many organizations are building innovation spaces where they spend a great deal of time with their customers and users to significantly improve their product offerings and to create new and exciting customer-centric innovations.

One example of customer cocreation is IKEA, the Swedish home furniture retailer. The success of IKEA’s business idea is simple and well known:

• Produce high-quality furniture by sourcing components worldwide.

• Match the creative capabilities of the different participants more efficiently and effectively.

This second part of IKEA’s business strategy leverages cocreation. IKEA offers its customers stylish products for a low price. It can do this by asking customers to take over a task that’s traditionally done by the manufacturer: the final assembly of the furniture. Asking customers to take over specific tasks in order to contribute value is a key to understanding the value of cocreation.

Are you leveraging the ideas and real-world product knowledge of your customers? If not, plug them into your innovation operating system. You’d be surprised how many of your customers have opinions about your products and services, and are willing to share them at no cost to you. That’s a deal you can’t refuse!

4. Crowdsourcing

Innovations can come from people you don’t even know. While the idea may give traditional managers the hives, allowing complete strangers to collectively work on a problem is becoming increasingly common. With the rise of the internet as a reliable global platform, we’ve seen the emergence of company interactions with crowds on innovation projects in areas as diverse as mobile apps, video games, enterprise software development, genomics, operations research, predictive analytics, and marketing.

In many situations, crowdsourcing can be more efficient and yield better results than in-house innovation.

Companies, especially established corporations, tend to be relatively well-organized environments for the collecting and leveraging of specialized knowledge to seize innovation opportunities and address problems. The downside is that innovative power may be constricted by preconceptions and assumptions about what can work and what won’t work. The ability to innovate may also be limited by the number of employees or other stakeholders.

In contrast, a plugged-in crowd is fluid and decentralized. You can present a problem to widely diverse individuals who possess a variety of experience, skills, and perspectives. The crowd can operate at a scale larger than that of even the biggest and most complex global corporation, bringing in many more individuals to focus on a given challenge.

As Kevin J. Boudreau and Karim R. Lakhani noted in Harvard Business Review, innovation through crowdsourcing generally takes one of four distinct forms: contest, collaborative community, complementor, or labor market. Each one has its own characteristics and strong points:30

Contest. In an innovation contest, an organizer seeks solutions to an innovation-related problem from a group of independent individuals. The two most important decisions of the organizer are whether to provide awards and whether to restrict entry or run an open contest.

A contest can involve either individuals submitting new ideas for consideration or voting on a set of solutions curated by the organizer.

For example, the Climate CoLab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is an open problem-solving platform where a growing community of over ninety thousand people, including hundreds of the world’s leading experts on climate change and related fields, work on and evaluate plans to impact global climate change. As the Climate CoLab says on its website, “In the same way that Linux welcomes thousands of software developers to help build its operating system, and that Wikipedia lets anyone edit the world’s largest encyclopedia, Climate CoLab enables thousands of people and organizations from around the world to help build such implementation plans.”31

Anyone can join Climate CoLab’s open community and participate. If you see a proposal you like on the Climate CoLab website, you can support it. After the internal judges select finalists, you can vote for the proposals you like best. You can comment on any proposal, and to some you can also contribute if you join the team. If you have a good idea, you can even start your own proposal.

In August 2016, the grand prize winner of the Smart Zero Carbon Cities Challenge was Climate Smart, a software project with the goal to “create a dashboard that allows cities to understand their business emissions by sector, business size, emissions source, and track progress.”32

Collaborative community. Here, individuals volunteer to solve a problem or improve an existing product. A good example of this is Wikipedia. The internet-based encyclopedia has destroyed the traditional model of encyclopedias (remember the multivolume World Book that sat on your living room shelf when you were a kid?), thanks to global, highly diverse collaboration within a new organizational model. The size of the Wikipedia editing community, with multiple people typically reviewing any given article according to organizational guidelines, ensures a thorough monitoring of content quality. Wikipedia uses an automated process to coordinate and aggregate the crowd’s edits and keep track of all changes.33

Collaborative communities are most effective when participants can share information freely as they accumulate and recombine ideas. This means that protecting intellectual property is very difficult.

Crowd complementors. These are businesses that directly sell a product or service that complement the product or service of another company, by adding value to mutual customers.

The most familiar examples are the thousands of third-party apps you can get for your smartphone. The number one smartphone app of all time is (drumroll, please) . . . Angry Birds, which made its debut in December 2009. As of this writing, the various games in the series have been downloaded over three billion times. It’s a “freemium” app, which means the initial app game is free, but you pay for upgrades and extra features.34

Crowd complementors are nothing new. Back in 1909 when Ford introduced the Model T, the car itself was deliberately kept very basic and affordable. As millions of Model Ts rolled off the assembly lines, almost instantly independent crowd complementors rushed to create a huge aftermarket of Model T accessories. These companies made everything from bumpers (not originally offered on the Model T) to engine parts, brakes, seats, and body adaptations—all to be sold to owners of the Model T who wanted to spend a few more dollars to improve their car.

Ford didn’t develop, own, or sell these products. But by allowing the crowd to innovate and produce complementary products to the organization’s main product, an organization can increase demand for that main product. For example, you’re more likely to buy a particular phone if you know it will work with all of your favorite apps.

In this model, intellectual property may be protected by API (application programming interfaces) and developer agreements. This model has become familiar with the App Store, and it is most effective when a high variety and quantity of complements creates value for the core product.

Although this type of crowdsourcing can be difficult to manage, understanding the purpose and best use can direct the risk management team to successfully implement this solution.

Crowd labor markets. This is where you enlist the talents of self-employed freelance workers to solve a problem or do a job. You do this by accessing a third-party intermediary such as Upwork, Guru, Clickworker, ShortTask, Samasource, Freelancer, and CloudCrowd. These highly flexible platforms serve as spot markets, matching skills to tasks. They have become big business: based in Mountain View and San Francisco, California, Upwork has twelve million registered freelancers and five million registered clients. Three million jobs are posted annually, worth a total of $1 billion.35

5. Open Innovation

Open innovation requires that innovators integrate their ideas, expertise, and skills with those of others outside the organization to deliver the result to the marketplace, using the most effective means possible.

A simple example is the buying or licensing of processes or inventions (patents) from other companies. In this case, innovation is brought into the company from an external source. Open innovation can also flow the other way. Companies can commercialize internal ideas by using channels outside of their current businesses. These may include startup companies financed and staffed with some of the company’s own personnel, or licensing agreements, where a technology that the company isn’t using is licensed to an outside firm that may even be a competitor.

Excess capacity can be offered to customers. For example, Amazon Web Services (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon that provides on-demand cloud-computing platforms to individuals, companies, and governments, on a paid subscription basis. The idea originated in late 2003, when Amazon engineers Chris Pinkham and Benjamin Black proposed selling access to virtual servers as a service, allowing the company to generate revenue from the new infrastructure investment.36

Companies can also use open innovation tools. Numerous open innovation service providers offer both sophisticated models of assistance and simple websites to post ideas. Players in this arena include such names as NineSigma, InnoCentive, the InnovationXchange, and Planet Eureka.

For example, Sealed Air Corporation is a packaging company known for brands including Cryovac food packaging, Bubble Wrap cushioning, and Diversey cleaning and hygiene. They have an in-house R&D team, but they also work with NineSigma, a company that designs and manages open innovation solutions for organizations in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

As Blaine Childress, Sealed Air research scientist and coordinator of the firm’s open innovation efforts, told IndustryWeek, the company’s marketing people identified the need for a special valve for a package. Internal R&D people worked to develop a solution, but given the number of technical, timing, and cost issues, “they just really weren’t able to quite get there in the time frame that was needed,” said Childress. “People were becoming more and more loaded with other problems with short timelines.”37

The company made the decision to post the problem to the NineSigma global solver network. They got a dozen responses from all over the world. They reviewed them, and within nine months the company had a solution they could use.

To fulfill the Innovation Mandate, you don’t have to have a bunch of scientists working in a secret laboratory deep within the bowels of your headquarters. You can harness outside ideas to advance your own organization. All it takes is a little imagination and planning.

INNOVATE . . . WITH SAND!

Recently, our team spent time working with a client who was the CEO of a big company that sold construction aggregates—basically, sand and gravel.

Yes, sand and gravel. It’s a ubiquitous commodity. There’s not much you can do to improve the product. The stuff hasn’t changed since they built the pyramids.

The CEO, whom we’ll call John, wasn’t happy with his margins. Every year, it was getting more difficult to turn a profit. Demand was good, but his costs were creeping inexorably higher. Fuel and labor costs were the two biggest problems.

We said to John, “You need to innovate. Stay ahead of the curve. Take a fresh look at every area of your operation.”

“Innovate?” he replied. “Do you mean invent a new type of rock? I don’t think so. My customers in the construction industry are very specific about what they want. I sell granular subbase, pea gravel, crushed stone, quarry process, riprap stone. Period. It’s all by the book.”

We understood what he meant. But we explained that innovation isn’t just about new inventions. In fact, the vast majority of innovations have nothing to do with products. Organizations innovate in countless ways. They improve their supply chain, or their human resources policies, or their marketing campaigns. Sometimes they transform the company’s management structure. Or they explore a new way to use a ubiquitous product and sell it into a new market.

“Okay,” he said. He was curious—a good sign.

“How do you ship your product over long distances?” we asked him. “Say, a few hundred miles along the coast?”

“We use oceangoing commodity vessels, like everyone else. Or we use trucks. They cost a fortune, but what can you do?” He shrugged.

“You can innovate, just like the Norwegian chemicals group Yara.”

“What are they doing?”

“To haul their fertilizer,” we said, “the company is building an autonomous, battery-powered container ship. By the year 2020, it will be able to operate without a human crew. The new vessel, named the Yara Birkeland, will replace forty thousand diesel truck journeys the company makes hauling fertilizer from its plant to ports every year.”38

“Really? It will sail itself?”

“Along the coastline, yes. There are many other innovations happening in global cargo supply chains. In Europe, a collaborative multinational project is creating a fleet of self-driving trucks that will transport goods from ports to destinations inland. In Singapore, one of the world’s busiest ports, autonomous trucks haul containers between terminals. Rolls-Royce is developing what it calls ‘intelligent ships’ that will be ready for service by the year 2020. Big innovations in the transportation of heavy cargo are happening—and you should be a part of it!”39

John developed a new attitude about innovation. He realized that even though he was in the construction aggregates business, he had many opportunities to leverage new technology and new business approaches to boost revenues and trim costs. While the sand he sold was the same stuff used to make concrete in ancient Rome, how he sold it made a huge difference in his ability to serve his customers, deliver value, and make a profit.

He embraced the Innovation Mandate.