Everyone in business knows the value of systems.

A system is a repeatable process in your business that can theoretically take place without the direct action of a leader or manager. A system is a method of doing something that can be done the same way, over and over, as efficiently as possible. It allows leaders to focus on future growth and moving beyond mere survival to true prosperity.

The alternative to a well-constructed system is chaos. This is the painful condition known to both startups and big corporations, where every day you need to reinvent the wheel. Instead of coaxing the spark of innovation to life, you’re running around putting out damaging fires. You can’t plan for the future because you’re too busy managing the present and its many small crises.

Systems can be simple or complex. A simple example in a small business might be an email autoresponder sequence that nurtures a relationship between you and the people who subscribe to your mailing list. It might be a system that triggers an invoice when a certain part of a project is marked as complete.

The bigger the business, the more systems it will have. Big companies have systems for supply chain, sales, production, hiring, branding, marketing—just about every facet of their operations.

Companies that are built on a franchise model are nothing but systems. If you’re just counting the number of franchisees, the reigning king of the franchise world is 7-Eleven. With fifty-eight thousand stores operating in seventeen countries worldwide, 7-Eleven has its systems fine-tuned. If you want to open your own 7-Eleven, pretty much all you have to do is plunk down anywhere from $37,550 to $1.2 million (depending on location and other variables), get the 7-Eleven training, and unlock your front door! Services provided by the home office in Dallas, Texas, include obtaining and bearing the ongoing cost of the land, building, and store equipment; record keeping, bill paying, and payroll services for store operations; and fees and financing for all normal store-operating expenses. The head office for 7-Eleven even pays for the franchisee’s water, sewer, gas, and electric utilities.1

They’ve got their systems fine-tuned to a science.

But having massive operational systems does not by itself guarantee success. Just ask Blockbuster. At its height in 2004, the video rental franchise giant employed 84,300 people worldwide and had 9,094 stores in total, with more than 4,500 of these in the United States. They ruled the video rental business! But the market vanished, their business systems became obsolete, and in 2010 the company declared bankruptcy.

Some companies—but not nearly enough!—have systems for innovation. But I’ll get to that in a moment.

THE BEST SYSTEMS ARE FLEXIBLE

In many ways, systems are amazingly good.

Without systems, people have to solve the same problem over and over again. Systems ensure consistency, promote thrift, and reduce repetitive tasks that don’t add value. They guarantee that when you order a Big Mac in Boise, it’s the same Big Mac that you’ll get in Baton Rouge or Bangor. It also means that McDonald’s can scale up production of Big Macs and accurately predict the profit margin regardless of whether the Big Mac is sold in Topeka or Tokyo.

But systems can easily turn nasty. They can change from being a friend of an organization to being its worst enemy.

They can become entrenched and resistant to progress. When external conditions change—as they are in today’s business environment with increasing speed and depth—people can cling to established systems in the false belief that what is “tried and true” will save the day.

Russell Ackoff, one of the pioneers of business systems, warned against organizational silos, sclerosis, and fragmentation. Ackoff defined the systems age as beginning after World War II, during a time of growing global and technological complexity. Organizations would henceforth have to deal with “sets of interacting problems,” and the key challenge would be designing systems that would learn and adapt. He said, “Experience is not the best teacher; it is not even a good teacher. It is too slow, too imprecise, and too ambiguous.” Organizations need to learn and adapt through experimentation, which he said “is faster, more precise, and less ambiguous. We have to design systems which are managed experimentally, as opposed to experientially.”2

The moral of this story is that while systems are mandatory for any thriving business, these systems must be agile. They must bend, not break. They must be capable of being reinvented as conditions change.

For any of these conditions to be met, a system must be as simple as possible.

THE USER-FRIENDLY APPLE OPERATING SYSTEM

Remember those ancient days before everyone had a smartphone or even a home computer?

Back in the Dark Ages of the 1970s, when computers were beginning to be made in sizes smaller than a refrigerator, the biggest obstacle to their use by ordinary people was their complexity. You had to learn to use command-line prompts to drive the operating system. Punch cards ruled, and while desktop calculators did the math, typewriters did the word processing.

Apple made using a computer intuitive. The Mac operating system, with its desktop and bitmapped graphical displays, was far easier to use and required less training and expertise than the ubiquitous DOS systems. The Mac was the first truly popular computer with a graphical user interface, a mouse, and the ability to show you what a printed document would look like before you printed it.

What this meant is that the user could, without any special computer training, easily master the system and be productive. The user didn’t have to expend time and energy learning how to perform a task. The best industrial systems are like that—they’re as simple and easy to learn as possible.

Innovation must also be sustained over time. Again, look at Apple. Today the company makes the one computer in the world that is as easy to use as a toaster—the iPhone. The most revolutionary thing about Apple’s first iPhone was the seemingly effortless way in which nearly every bit of complexity was hidden behind a display of easy-to-understand icons. The iPhone contained no visible “directory structure.” Your music was not in a particular place on your phone, requiring you to hunt for it; you accessed it by launching the music player with one touch.

COMPLEX MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS CAN BE DEADLY

In a successful Innovation Mandate, you’ll find simple systems that deliver exceptional enterprise value. This includes not only R&D and production systems but management systems.

This seems like an obvious formulation, but all too often organizations get tangled up in complicated and bureaucratic systems that actually stifle innovation.

The classic example of bureaucracy stifling innovation—with tragic results—is the General Motors ignition switch scandal of the early part of this century. Eventually, GM had to recall nearly thirty million cars worldwide and the company paid compensation for 124 deaths.

The fault had been known to GM for at least a decade prior to the recall being declared. The problem was unintended ignition switch shut-off because a part called the “switch detent plunger,” designed to provide enough mechanical resistance to prevent accidental rotation, was insufficient.

According to an email chain from 2005 unearthed by investigators, GM’s managers estimated that replacing the key ignition switch component would cost ninety cents per car but only save ten to fifteen cents on warranty costs. Somewhere deep in the bowels of the vast GM bureaucracy, the fix was repeatedly rejected until 2006—but millions of earlier cars weren’t recalled.3

Remember—innovation is not narrowly defined as “a new invention that no one has ever seen before.” That’s much too limiting. Innovation includes identifying problems and fixing them. It means making a change to the status quo to add value to the product or service.

FOUR OBSTACLES TO INNOVATION—AND THE SOLUTIONS

Systems can be beneficial or they can hold you back. They can be written down in company manuals, like the comprehensive systems used by 7-Eleven, or they can reside in the guts of the company culture. The latter variety often takes the form of institutional knowledge, or to put it in familiar terms, “That’s the way we do it around here.”

If “the way we do it around here” is supportive of innovation, that’s good.

If it means being stuck in a rut, that’s bad.

A system for innovation must be capable of taking the spark of a new idea and developing it into a source of energy. There are at least four significant reasons why corporate innovation is so difficult—but for every problem there’s a solution.

1. Previous Success

Problem: When you sell a product and it does well, you’ve now set the bar. You’ve hit goals that you want to exceed in the future. This can create a mentality of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The organization learns and codifies what made it successful, which locks in a way of doing business and a set of expectations about current and future success.

Solution: It’s understandable that it can be difficult to tinker with a successful product, which is why many leading innovators like 3M aim to generate a set amount of revenues from new products. In addition, as we can see with many innovative manufacturers like Toyota and, more recently, just about every other car manufacturer, massive innovations happen in the production process, out of sight of the consumer. While Toyotas change very little in their exterior appearance from year to year, improvements are always being made under the hood.

If you have a successful product that people love, you’re well advised to carefully preserve your market and your brand appeal. But there are still plenty of ways you should be innovating behind the scenes!

2. Catering to the Existing Customer

Problem: Everyone knows that it costs more to acquire a new customer as opposed to keeping an existing one. You know what existing customers want and it’s easy to give it to them.

For an entrepreneur, every consumer is a prospect, and there’s no infrastructure or product portfolio to support or defend. But established firms, having achieved sales success and having built a product portfolio, want to lock in their customers. They’re more inclined to defend their existing customer base rather than innovate to offer new solutions to new customers.

Solution: The innovative organization knows that consumer tastes change—often dramatically! Consider the soft drink industry. You’d think that Coca-Cola was a foolproof product with decades of customer loyalty. Nope! Sales of the company’s iconic soft drinks have been sagging for over twenty years as consumers seek healthier beverages. Sandy Douglas, the company’s top North America executive, told trade publication Beverage Digest that Coca-Cola is “moving at the speed of the consumer” in its flagship market by evolving both its business model and how it measures success. Shifts in the consumer landscape have inspired the beverage giant to rethink its core success metrics. “We will measure ourselves on what people are willing to pay for our products, not the gallons they purchase,” said Douglas. “If you follow your consumer, you’re likely to have a good day.”

3. Resource Allocation and Project Prioritization

Problem: In any organization, there’s only so much money, time, and resources to go around. Corporate innovators often find themselves fighting for limited funds, since the vast majority of resources and dollars are going to support existing products—the cash cows. In addition, executives often can’t decide between innovation projects. This leads to half-hearted initiatives and piecemeal innovation that is either ineffective or doomed to fail.

Solution: This is where leaders need to step up and define the culture of the organization. It’s incredibly foolish to expect that your product or service will be the same in five or ten years as it is today. To meet the challenge of inevitable massive change, leaders need to mandate an investment in innovation with the understanding that new ideas are the lifeblood of the business and are worth paying for. Leaders need to look ahead and take the necessary steps to not only cope with change but to leverage it.

Some industries, such as pharmaceuticals and entertainment, know their products are destined to lose value over time, and that creating new products—proprietary drugs, movies, popular music—is the only way to survive. They know they must innovate or die. It’s a liberating feeling!

4. Leaders and Employees Are Stubborn

Problem: People can be rigid and set in their ways! Both leaders and employees can have a fear of failure or simply an aversion to changing how they do their work. They get set in their ways, and view innovation as a painful intrusion into their comfortable routine.

Solution: Do you know what’s really painful? Going out of business because of a failure to keep pace with the inexorable changes that happen in every marketplace. That’s painful for everyone.

To create a strong Innovation Mandate, leaders need to be proactive about connecting with their stakeholders. Employees need to fully understand what innovation means and how it’s going to be managed in their organization. When there are gaps in that information, employees get nervous and rumors start to spread. Leaders need to clarify gray areas and make sure misinformation isn’t spreading.

Call a team meeting and explain what’s going on in a clear and concise manner. If your company is big, train your managers to do it. Imagine you’re pitching your idea to potential investors—after all, your employees are being asked to invest their time and even their hopes—and start at the beginning. Discuss why innovation is important, and why you’re so excited about it. Employees who are afraid to think innovatively won’t. Traditional employee training and development often do not include support for idea generation and encouragement to think differently. If you want your company to be truly innovative, then put in place the environment that allows your top managers to teach innovative thinking to their people. If you want to foster an environment of idea generation, then you need to encourage new and risky ideas to be voiced.

Make your innovation operating system no different from any other system in your organization. Fund it properly, educate your stakeholders, and make it simple. Set attainable goals and celebrate both successes and failures. Bring the spark of innovation to every part of your organization and see the powerful results.

ACT, MAKE, IMPACT: THE INNOVATION ECOSYSTEM

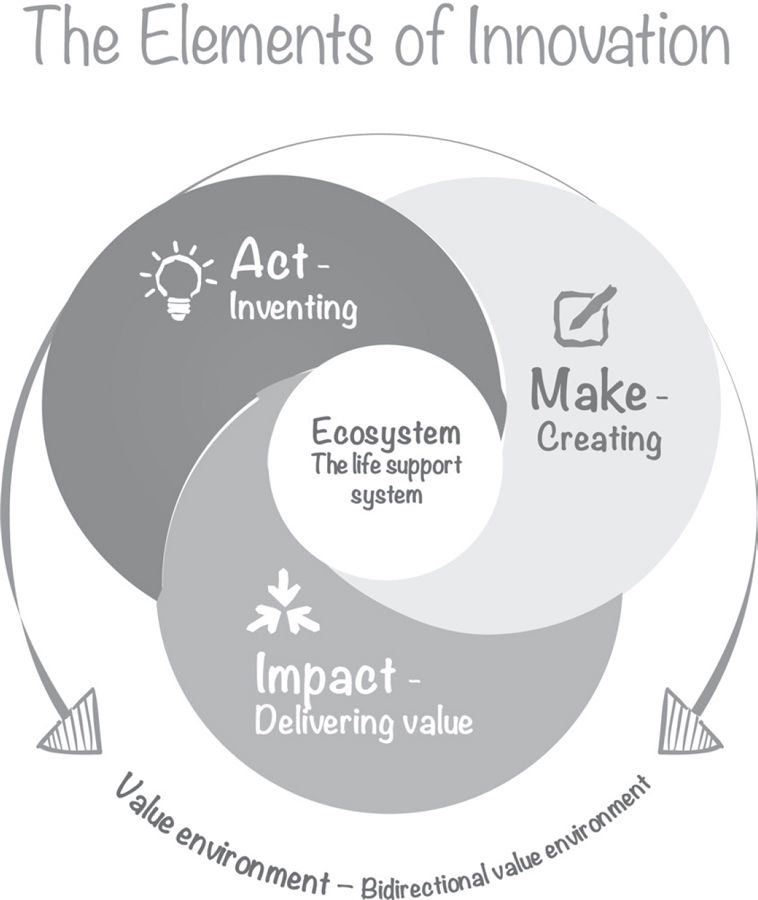

Just like a computer needs a frame for support and a case to enclose it, your innovation operating system will need a broad, overarching structure. A simple framework that gives it shape and makes it easy to conceptualize. Something that’s easy to diagram.

It’s the innovation ecosystem.

To support sustainable and successful innovation, your organization needs a comprehensive innovation ecosystem. It’s the organization’s systems, processes, tools, enabling technologies, culture, people, and anything else that provides the life support system for innovation to succeed. Innovative organizations have robust and complete innovation ecosystems, providing the necessary nutrients and culture to drive sustainable enterprise innovation.

You’re not likely to act on innovation without the proper ecosystem providing support, and you will not be able to make an impact without the right infrastructure. The ecosystem includes two bidirectional relationships: between external customers and the organization, and between external innovators in the organization in the form of the value environment.

The value environment is not just the marketplace you serve; it’s also composed of external innovators and partners with whom you connect in a very bidirectional way. In other words, innovation is very much a two-way street. The best organizations in the world collaborate with external partners, customers, innovators, and even competitors to find new ways to create meaningful enterprise and customer value.

The innovation ecosystem is composed of three equally important phases.

Act

Fed by customer and market insights, business goals, and other external forces, the act of innovation comprises everything related to creating or identifying potential innovations.

It begins with a small spark of an idea that may deliver value to our organization, our mission, and our customer, and then we refine it. Innovation can occur through a wide range of activities that include design thinking, ideation, serendipitous innovation, planned innovation, new product development processes, hackathons, ideation that leverages game mechanics, social innovation, crowdsourcing—the list goes on and on.

Then you determine whether the idea has the potential to hit a target—that is to say, fulfill a need, solve a problem, or create an opportunity. Once you’ve identified the need, problem, or opportunity, then you can leverage the act of inventing to move you closer to an innovation that delivers real value.

The innovation process should be as complete as possible and should continue to identify ways to add both layered and dynamic value.

Layered value, or value stacking, is the process of adding more value to an idea, ideally without adding additional cost or complexity. Remember that the market is looking for the most value at the lowest cost.

Dynamic value suggests value that actually makes the product, technology, or solution always get better. Your iPhone is probably more valuable today than it was last week. Why? Because Apple has a community of financially engaged external app developers constantly creating a wide range of new apps to make the user’s life better at a very low cost, or in many cases at no cost.

The act phase includes the spark generator and fast filter of the innovation pipeline, in which the organization screens ideas to determine if they meet the qualifications of acceptable innovations. For example, an automobile company may have an idea for a great motorcycle, but it may not be a fit given their lack of market expertise and distribution channels. In the innovation pipeline, we start with the directionless spark, and then we move into the assessment and optimization phases.

Make

Make refers to everything related to the creation or implementation of an innovation. It speaks to the process of transmuting ideas into genuine value to the organization and the customers it serves.

In this phase, you will begin the process of taking your design concept and moving it into development. During this phase, you will be gaining insights to verify the business case for your idea. Even if your idea isn’t a bright shiny object, you’ll need to continue to determine if the innovation serves the intended target.

For example, you may be looking for ways to get clean drinking water to an underserved population in South America. The underserved population is a potential customer base, and you need to be able to distribute and deliver your innovative product. The make phase, as with the active inventing phase, requires that you constantly verify your original value proposition. During the make phase of a new product, you will be optimizing your idea by looking at everything from the best manufacturing methods, materials, packaging, cost of goods sold, financial analysis, surveys, and focus data from customers and everything else that’s necessary to make sure there is a business case for your idea.

Your new product innovation has to thrive in an external marketplace with demanding customers and fierce competition. Many viable innovations fail because they were launched to the marketplace before they were done “cooking.” Be sure to optimize your innovation before transferring it to the impact phase.

You should also avoid personally evaluating the market viability of your innovation, as you probably won’t be able to be objective. During this phase, you may be using traditional new product development methods; some of the most common are referred to as “stage gate,” or our preferred method, the opportunity pipeline. The idea of these linear processes is to allow you to go through the evaluation of your idea to verify its business case while concurrently improving the design through dynamic innovation and layering or stacking the innovation.

Impact

Impact is how effectively you take the innovation to the marketplace and create sustainable value. For example, if you’ve invented a new process to increase efficiency on an assembly line, then you would have to determine how to apply the idea to that process in a way that either enhances the value to the customer or allows you to charge the customer a lower price for your product. The same is true with any product, technology, marketing innovation, or any other type of idea. If it doesn’t have a positive impact on your organization or customer, it’s not an innovation.

The impact phase is where you create the market life support system for your innovation. This is an important phase, as some of the best innovations are not new inventions but rather innovative business models or delivery mechanisms. For example, Uber did not reinvent the automobile; they created a new ride-for-hire model that connected car owners with customers who were looking for transportation. Likewise, Netflix did not reinvent the internet; they invented a new approach toward delivering content by leveraging digital connectivity.

The goal of any new product innovation is to positively impact the customer. Your marketing strategy, channel strategy, distribution options, engagement strategies, and all the other elements that go into releasing your innovation to the marketplace will be critical to its success. Give your innovation a fighting chance by building out a comprehensive impact plan that addresses all of the aspects of what’s necessary to deliver exceptional innovations in a time of market disruption.

In a time of massive market disruption, your innovation needs to be highly differentiated and layered with dynamic value. Before you launch, get real insights about how the market and your customers will perceive your innovation. Optimize your innovation through better channel, distribution, packaging, and other adjunct innovations.

And always be realistic about market projections and customer acceptance!

LESSONS FROM THE WORLD’S BIGGEST NURSING HACKATHON

While at some companies hackathons are nothing more than gimmicks, truly innovative organizations, including Facebook, Hasbro, Unilever, PayPal, the American Nursing Association (ANA), and others, effectively use hackathons as part of a robust innovation operating system. Their hackathons work because the companies are committed to innovation, and they’re just one tool in the kit.

The American Nursing Association does an amazing job of serving their members by helping them leverage the skill sets and the insights that will affect the way in which they deliver safe and efficacious care. A great example of their embrace of the spark of innovation was the world’s biggest nursing hackathon, held in March 2018 in Orlando, Florida.

In this case, eight hundred participants used innovative thinking to determine ways to advance safe patient handling and mobility, prevent violence against nurses, strengthen moral resilience and ethical practice, and protect health-care workers against needlestick and sharps injuries. Nurses initially generated ideas on their own at group tables, and in a succession of votes, whittled them down to winning solutions.

This ANA hackathon was no small matter, as historically innovation has too often lived only in the corner offices of hospitals and clinics. The ANA recognizes that, every single day, nurses get unfiltered, firsthand knowledge of problems and opportunities. On both a short-term and long-term basis, they work closely with patients. (In other industries, they’re called customers.) Because of their frontline experience, practicing nurses have more ideas on how to make things better for the nurse, doctor, patient, and organization than anyone else.

During the hackathon, these amazing nurses unleashed their innate power to innovate, solve problems, and identify new opportunities. “We need to get people to believe in their own creativity,” said Karen Tilstra, PhD, co-founder of the Florida Hospital Innovation Lab, where nurses and others can bring their challenges and innovate solutions. “Innovation is always a step in the dark,” she added. “It takes courage. But you don’t have to know everything to start finding solutions.”4

As the ANA reported, here are just a few examples of nurses’ innovative thinking from the Orlando hackathon:5

• A relaxing virtual reality room where nurses can take a break from their unit

• An app in which nurses could report any violent incidents, as well as track the total number of incidents in twenty-four hours

• Gloves that serve as armor against needlesticks and sharps injuries

Are any of these ideas seismic or disruptive? Probably not.

Could these incremental ideas (and others), when accumulated and applied consistently day after day, make a huge difference to an organization’s ability to deliver value to its customers and drive up profits?

Absolutely yes!

The hackathon was an amazing example of opening the floodgates of ideas to get new perspectives from the very individuals who have the best actionable insights to drive innovation. We are now seeing this process ramp up as more and more organizations are beginning to see that collaborative organizations that build out simple but powerful innovation pipelines are constantly leading their markets and new innovations in customer satisfaction.