The first question leaders often ask is this: “Where does innovation spark?” And the second question is, “How do we manage it and make it profitable?”

The answer to both questions is the innovation pipeline.

Pipelines in business are nothing new—here are three examples:

1. A product pipeline manages the development and marketing of new products. One of the clearest examples of product pipelines is in the pharmaceutical industry, where firms are constantly looking to develop new drugs for the market, and the process of development to sale goes through well-defined steps. You’ll see robust product pipelines in consumer electronics, aerospace, the automotive industry, the entertainment industry—in fact, just about any industry where products have life cycles and new products must be developed to either replace the old ones or add to an existing product line.

2. A leadership pipeline is a standard feature in most large organizations. The recruiting, training, deploying, and reviewing of leaders is a necessary process for the long-term success of any company. A good leadership pipeline will manage every phase of leadership opportunities from new member to senior staff, and provide a detailed road map for each person interested in pursuing leadership within the organization.

3. A sales pipeline tracks and manages the life cycle of the customer experience, from initial interaction to closing the deal. These steps include gathering incoming sales leads, qualifying prospects into sales-qualified leads, validating a qualified lead into a sales opportunity, and then registering the deal as closed, on hold, or lost. It also manages repeat customers and identifies opportunities to upsell them.

The expected outcomes of a sales pipeline are typically measured by four metrics:

1. The number of prospects or possible sales in the pipeline

2. The average size of a sale in the pipeline

3. The average close ratio, or the average percentage of sales that are made

4. Sales velocity, meaning the average amount of time it takes to make a sale. This is important, because, all other factors being equal, making ten sales per day is obviously better than making one sale per day.

It’s easy to see that if you’re in business, you already know the importance of pipelines! An innovation pipeline is no different. It has a purpose and a structure, and there are ways to measure its effectiveness. All you need to do is transfer what you already know about business pipelines to the realm of innovation.

WHERE INNOVATION SPARKS

But let’s go back to the first question: “Where does innovation spark?”

In the first chapter of this book, we discussed this important topic. Innovation can spark in many places and under a wide variety of conditions. They include:

1. From the lab. In many companies, innovation is meticulously planned, and typically takes the form of an effort to find a solution for a specific, known problem. This is particularly true in pharmaceutical companies, where bringing a new drug to market takes a huge investment in time and money.

But planned innovations aren’t just expensive R&D programs. Toyota’s Creative Idea and Suggestion System is a form of planned innovation in which the rate of spontaneous new ideas has become predictable, and while the exact ideas are not known until they’re submitted, the overall idea flow is entirely planned and has been formalized into the company’s operations.1

2. Out of the blue. These are unplanned breakthroughs or new ideas that defy prediction. In familiar industries, many examples have become legendary. But unexpected innovation can happen anywhere. Take musical theater—not always innovative, and always risky. By bringing the rhythms and attitude of hip-hop to the otherwise stodgy historical biography of Alexander Hamilton, composer, lyricist, and actor Lin-Manuel Miranda created an electrifying crossover product in the form of Hamilton, the hit musical that is consistently selling out and bringing in nearly $100 million a year in gross revenues. To date, on an initial investment of about $12.5 million, the show’s investors have made unprecedented returns of roughly 600 percent!2

Hip-hop music and the Founding Fathers—who would have guessed?

3. Collaboration with partners. Companies are increasingly regarding stakeholders as partners in new product or service development. Customers, suppliers, and end-users often have significant skills and knowledge that can be leveraged for innovation development.

Organizations are beginning to cocreate with brands from other markets to create an opportunity for the respective businesses and the customers they serve. Successful brand collaboration depends on both brands benefitting from the existing market of the other, or by filling an opening in the market through a collaborative relationship.

Many organizations are building innovation spaces where they actually spend a great deal of time with their customers and users to significantly improve their product offering and create new and exciting customer-centric innovations.

4. Crowdsourcing. With the rise of the internet as a reliable global platform, we’ve seen the emergence of company interactions with external crowds on innovation projects in diverse business areas. Crowdsourcing can take the form of contests, collaborative communities, complementors, or freelance labor markets. Each one has its own characteristics and strong points.

5. Open innovation. Promoted by Henry Chesbrough in his book Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, open innovation requires that innovators integrate their ideas, expertise, and skills with those of others outside the organization to deliver the result to the marketplace, using the most effective means possible.3

Does managing innovation seem like herding cats?

Perhaps. But it doesn’t have to!

You just need to be organized and have a robust innovation pipeline.

THE STRATEGIC CASE

In building an innovation pipeline, the first step is to know two things:

1. Why you’re doing it

2. What you hope to get out of it

The strategic case is at the very core of the innovation process. It provides guidance on what an organization wants to achieve with innovation. It includes high-level technology, market, and industry assessments. Strategic analysis is not to be confused with market research, as the latter includes more focused investigation of market size and market segments.

An innovation effort may be carefully planned to find a solution for a known problem, such as developing a drug to fight a certain disease.

It may have the goal of finding unexpected and unforeseen innovations, either as products or as process innovations that either save the company money or add value for the customer.

Whatever it is, at the end of the day any innovation must satisfy our ironclad definition:

Innovation is the creation of new value that serves your organization’s mission and customer.

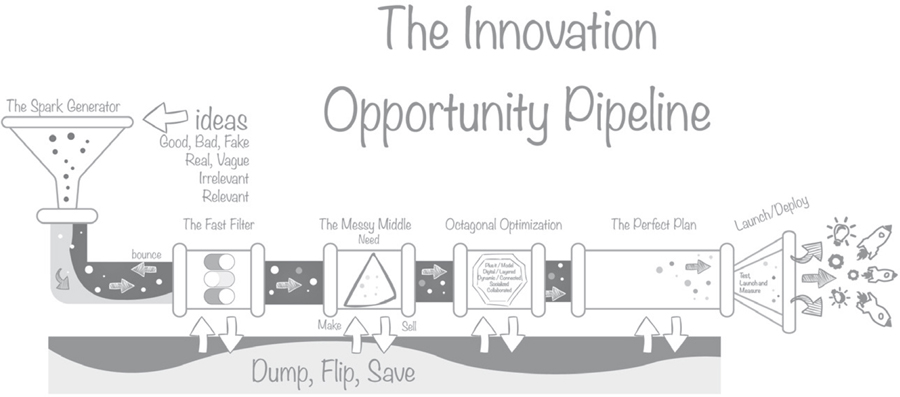

Your innovation pipeline will consist of five phases that enable your organization to identify, capture, validate, develop, and deploy the new ideas that will keep you highly relevant to your market and ahead of the competition.

The five phases are:

1. The Spark Generator

2. Fast Filter

3. The Messy Middle

4. Octagon Optimization

5. The Perfect Plan

Let’s explore them!

1. The Spark Generator

Have you ever seen someone welding or fabricating steel, and the sparks are flying in every direction?

That’s what you want. At the entrance to your innovation pipeline, you want to see a cloud of dancing, brilliant sparks, coming from all directions and bouncing off each other. Some fly off into space, but many of them enter the pipeline.

Here at the entrance, all sparks are created equal. They come from the employee suggestion box, from customer comments on social media, from vendors, from competitors (the ideas you steal!), from the R&D people in the lab. No idea has any more validity than another.

In the world of project management, this is the “brainstorming” level. It’s where the team leader calls for ideas from everyone, and in a mad rush writes them all down on the whiteboard without thinking about them.

In the spark generator, quantity equals quality. The more the merrier! You want sparks flying like embers from a roaring bonfire, lighting up the night.

MEASURING THE INPUT

While the spark generator is a wild and untamed frontier, like everything else in business its performance needs to be measured. You need to know how many possible sparks can be collected during a given period of time, and how efficiently your pipeline is collecting sparks for processing.

In any business measurement, of course, three metrics are the most important:

1. Over time, are your results trending up (good!), staying flat (okay), or trending down (bad)?

2. Do your results meet your goal? If not, is your goal too high, or is performance too low?

3. How do you measure up against the marketplace and the competition? Are you a leader or a follower?

As you will see when you switch on your innovation pipeline and set innovation goals, you’ll need time for your results to “normalize.” As time passes, you may need to adjust your pipeline to meet the reality of what your organization can achieve. That’s perfectly okay!

There are many ways to measure the input into your innovation pipeline. Here are just a few:

1. Number of employee suggestions per week or month. This is perhaps the simplest metric, in which you solicit and then count the number of suggestions from employees. The ubiquitous employee suggestion box is a good example. There is virtually no upfront capital investment required other than the time the innovation champion or team spends collecting and reviewing the suggestions.

2. Number of customer comments and suggestions. Listen to your customers, especially the unhappy ones who complain on social media or review sites. Make sure your social media people reply to or acknowledge every comment or question. Your customers are giving you free insights and advice, which is cheaper than paying a consultant and probably more useful!

As Molly St. Louis wrote for Inc. magazine, Citibank aggressively courts its customers, and the feedback pays off. For example, from its customers the bank realized that mobile banking was spreading and becoming increasingly important to their customers. In response, the bank honed its user-friendly app, and in 2016 saw mobile banking increase by 50 percent and the number of downloaded apps double.4

3. Number of new inventions or products coming from your R&D labs. This is a straight ROI situation, and can be managed like any other functional area. The key is to properly recognize an innovation that can make a difference in the future, not just right now.

For example, in 1975, Steven Sasson, a young engineer at Eastman Kodak, invented the first working digital camera. It was an ungainly device, but it worked.

Kodak executives were not interested.

Then in 1989, Sasson and a colleague, Robert Hills, created the first modern digital single-lens reflex (SLR) camera that looked and functioned like a normal camera. It had a 1.2 megapixel sensor, and used image compression and memory cards.

The Kodak brass were still unconvinced. They didn’t want to undercut their sales of old-fashioned film. As Sasson told the New York Times, “Of course, the problem is pretty soon you won’t be able to sell film—and that was my position.”

While Kodak licensed its digital technology to other companies, for its own products it clung to its outdated business model and failed to ride the massive market disruption of digital cameras.

In January 2012, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.5

Don’t let this happen to you!

4. Number of innovations licensed from other companies. See #3, above. Apple’s pioneering QuickTake consumer digital camera, introduced in 1994, had the Apple label but was produced by Kodak. Time magazine called QuickTake “the first consumer digital camera.” When Apple couldn’t do something in-house, the company acquired innovation from third parties.6

5. Number of ideas from other sources including contests. Google “innovation contest winner” and you’ll get thirty million results! The idea is nothing new. One of the most historically significant crowdsourcing innovation contests was announced in London in 1714. The Longitude Act, administered by the Board of Longitude, sought solutions to the problem of determining a ship’s location on the open sea, out of sight of land. The contest ran for 114 years, and many rewards were paid out to individuals who offered verifiable improvements over existing methods.

Today, contests and other crowdsourcing methods are a significant source of new ideas for organizations of all types and sizes. They can be internal or open. In 2015, drug maker Pfizer used an internal innovation challenge to help create a new mobile tool for patients seeking to stop smoking. The company created a Shark Tank–style competition for its brand teams, which generated roughly one hundred ideas. The winning idea was an unbranded mobile smoking-cessation app developed with the American Lung Association.7

2. The Fast Filter

Now that you’ve got a shower of bright sparks flying around the spark generator of your innovation pipeline, what’s next?

How do you begin to evaluate and sort them, separating the ones that have potential from the ones that are obviously worthless?

This is a critically important phase. Why? Because it’s easy to either throw out ideas that are good or waste time on ideas that are bad. No one wants to do that!

Some organizations receive thousands of innovation submissions each year, and they are so backlogged that there is literally no way they will ever catch up. Sadly, in those piles of unexamined innovations, market-leading and enterprise-beneficial ideas are hiding. It’s like leaving money on the table.

As the name suggests, the fast filter must have two key attributes:

1. Speed. You need a system for quickly evaluating each idea, rendering a decision, and either discarding it or letting it pass through.

2. Accuracy. You need a system that will retain good ideas and reject bad ideas.

FLOW MANAGEMENT: THE TOGGLE SYSTEM

If you’ve ever seen a dam on a river, you know that a dam serves two functions: it holds back the great mass of water while letting a controlled amount of water get through. The water that is allowed to get through provides value, often in the form of hydroelectric power or irrigating farms downstream.

Your innovation pipeline is no different. You set up a series of controls to both manage the flow and develop the value of the ideas that you allow to proceed downstream.

Instead of dams, you could think in terms of toggle switches. Once you’ve done the heavy lifting of determining what you want, you can then easily set up binary “yes/no” toggles to determine if an innovation makes sense for you to even look at. This automates the most painful parts of innovation, which are sifting through the sand to find that one nugget of gold and then dealing with disappointed innovators.

Each toggle has two positions:

1. Discard the idea. In all probability, 80 percent of all ideas entering the fast filter will be rejected instantly. This is because either they don’t fit the established guidelines for acceptance (such as criteria for new inventions), or the innovation champion has reviewed them and found them obviously unsuitable or irrelevant.

2. Let the idea pass through because you accept it, or it needs more study, or it’s temporarily archived for later use. These will comprise about 20 percent of the ideas entering the fast filter.

As you can see, toggle position number two is nuanced.

Of all the ideas allowed to pass through, perhaps just one in ten will be immediately accepted. These will be ideas that:

• Are super-simple, inexpensive, and obviously good. Take, for example, the idea cited earlier in this book about British Airways descaling the toilet pipes on its planes, thus making them lighter. This is the type of idea where you smack yourself on the forehead and say, “Why didn’t we think of that before now?”

• Totally fit an agreed-upon set of criteria. Let’s say you’re looking for a new device to solve a problem on your production line, and a supplier responds with exactly what you need. Case closed.

The remaining 90 percent of ideas allowed to pass through the filter will need more study. Most ideas that you get will be incomplete, simply because they’re narrow solutions to a problem and the organizational ramifications haven’t been researched. For example, if someone suggests that you adopt a policy of flexible hours for your employees, if the idea seems appealing you’re going to want to study it carefully before making a decision.

TOGGLES: MANUAL OR AUTOMATED

The toggles are placed at every phase of the pipeline, from the spark generator all the way to the back end where the final decisions are made to keep or shelve an idea, product, or process. As we’ve seen in case studies such as the General Motors EV1 electric car, which was scrapped after 1,117 cars were built and leased to customers, the “kill” toggle can be located at the very end of the innovation pipeline, after significant investment has been made.8

However, the highest concentration of toggles will be found in the fast filter. This is simply because here the volume of ideas is the greatest and their variety the most extreme, and there’s the most urgency to separate the wheat from the chaff. In fact, the fast filter is nothing but a collection of toggles. That’s its only function.

Toggles can be either thrown manually or automated. Either way, the decision must be made based upon a set of predetermined rules followed either by a human being (innovation champion or committee) or a software program.

The idea of an automated toggle system should be familiar to anyone who has either worked in human resources in a big company or applied for a job at a big company. When advertising open positions, such organizations can receive thousands of résumés, and many employ digital applicant tracking systems as the first set of toggles. The scanning software looks for keywords in a résumé that match keywords used in the job description. So if you apply for a job as a software engineer and the job posting says they want experience with “middleware Java stack,” if your résumé doesn’t include the words “middleware Java stack,” it will be rejected.

Your innovation pipeline toggles can perform the same function. They can be completely customized to connect to a screening process, thereby allowing an organization to screen thousands of submissions without ever actually looking at the submissions.

3. The Messy Middle

Entering the messy middle are the sparks that have blazed their way through the spark generator and survived the fast filter. These are the ideas that are worth a small investment in time or resources to determine their value.

The messy middle is the complex and amorphous process of closely examining an innovation to determine if it has a chance of delivering value to your organization, your mission, and ultimately your customer.

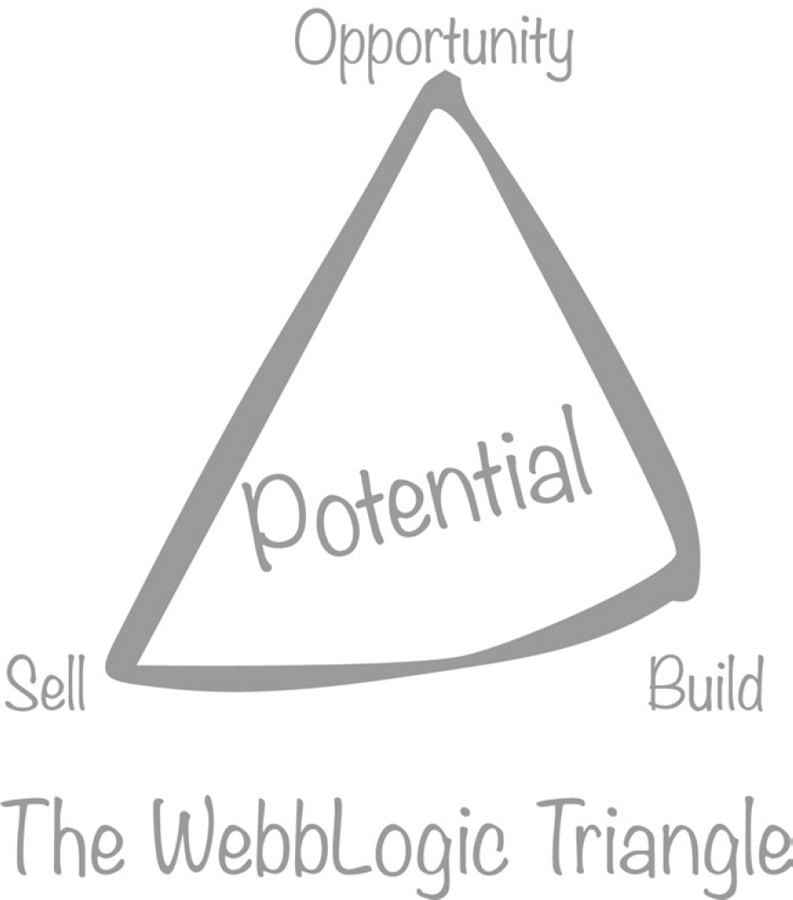

I’ve developed an exclusive program I humbly call WebbLogic that takes a three-dimensional approach toward evaluating the three most important aspects of innovation.

THE WEBBLOGIC MODEL

The biggest problem of most innovation evaluation tools is that they are 100 percent risk centric. They are more correctly seen as innovation prevention approaches. New ideas are judged solely on the basis of risk, and the higher the perceived risk—regardless of the possible benefit—the greater pressure there is to reject the idea and stick with the status quo.

There’s a better way to evaluate innovations.

Before you evaluate the suitability of an innovation for your organization, market, and customer, you must begin with your strategic case, which consists of the answers to as many of these key questions as apply to your organization:

• What does our customer want?

• What are the key competitive trends?

• What are the new enabling technologies that we can leverage?

• How much money do we have to develop and commercialize an idea?

• Does the new innovation square up with our organizational mission and strategies?

• Can we really deliver an innovation that provides exceptional market and customer value?

• Do we have the internal skill sets to evaluate the idea?

• Do we have all the information we need to determine if an idea is good?

• Do we have the team architecture to make the right choice on moving ideas forward?

This is just a small sampling of the possible questions that need to be answered as part of your overarching strategic case. Because your organization is unique, your strategic case will be tailored to your needs.

The WebbLogic model is a triangle consisting of a center plus three key areas of assessment.

Opportunity

At the top point of the triangle is Opportunity.

The best innovations meet a specific need or solve a problem. This creates an opportunity. Need or problem = opportunity. Without this you don’t have an idea.

One of the most common mistakes is making assumptions about an opportunity. Often organizations don’t gather sufficient information to determine whether a perceived need is widely recognized or even big enough to constitute a viable marketplace. In the old days we used to use a system called voice of the customer (VOC) to get information from potential customers as to whether they’d be interested in buying a product if the company actually made it. The problem is that it’s easy for a person being polled to say yes when they’re not being asked to actually spend money, so oftentimes organizations would get erroneous feedback about the potential marketability of a product or service. We need to go far beyond these old-fashioned risk-centric methods to really drill down to understand not the voice of the customer but rather the soul of the customer (SOC). We don’t care what they say or even what they think—what we really care about is what they believe and ultimately what they will do.

Sell

In the lower left-hand corner of the triangle is Sell.

Surprisingly, many innovators make broad and baseless assumptions about the marketability of an idea. The hysteria around an organization’s or inventor’s belief in the marketability of their idea can be astonishing. You need to be coldly objective about any idea that comes along, including your own.

I must confess I’m guilty of doing exactly what I’m asking you to avoid! A few years back I had the brilliant idea to take half a million dollars from my children’s college fund and invest it into an inflatable abdominal exercise device. I believed the risk was low, so I decided to do it. The product, Astro Abs, was to be sold on a single, one-time-only TV infomercial scheduled to air on a Saturday night. The commercial was expensive and beautifully filmed. I thought it was practically a work of art.

I’ll never forget that Sunday morning when the producer of the infomercial called me. I was standing in my backyard watching my five-year-old daughter, Taylor, swimming in the pool and having the time of her life. I heard the phone ring in the house. This was it—the call that would confirm my tremendous success! My wife, who was in the house, answered the phone. Then she came outside, phone in hand. On her face was a strange, stricken expression. Still expecting positive news, I took the phone from her.

In a somber voice, the producer said, “Sorry, Nick—it’s done.”

“What do you mean, ‘It’s done’?”

“The infomercial was a total flop. No one wanted the product. We sold nothing.”

Stunned, I thanked him and clicked off the phone. I had lost my entire investment. He did not see a way to resurrect the commercial messaging or the product. There would be no retest, no second opportunity.

I looked at my daughter and thought to myself, Oh my God, I just threw away your college fund!

Eventually I was able to replace her college fund, and in many ways this was possible because of the very lessons I had learned from that mistake.

The takeaway here is pretty simple: Fall out of love with your brilliant idea.

Love is an irrational emotion that will prevent you from honestly evaluating the marketability of your idea. Had I completed my due diligence on the inflatable abdominal exercise device, I would have been able to identify the problems and circumvent a major financial hit. You need to know if an idea will sell!

Many organizations conduct sterile research to draw conclusions about the marketability of a technology or service. A far better way is to actually ask someone to buy it now. Asking someone if they’re interested in the technology or service versus having them sign on the dotted line is quite a different thing. Take, for example, the crowdfunding site Kickstarter, which sells ideas to early adopters before entering production or even finishing the prototype. The old-fashioned way that we used to determine the market viability of a product is simply deficient, especially given the access to far better and more accurate information sources. Today we can instantly find out vital information, such as:

• The size of the market

• Online success and failure stories about similar products

• Industry trends that impact the marketability of a product

• Deep insights through online social networks

• Insights from social ratings and other empirical customer communities

Build

In the lower right-hand corner of the triangle is Build.

It’s safe to say that if you could build a perpetual motion machine, you’d be very successful in selling it. The problem is pesky old physics: a perpetual motion machine is a unicorn and will never be invented. It’s just against the laws of nature.

There are two questions you need to ask for every innovative product:

1. “Can we build it?” This question can be significant—just ask Elon Musk, who with his company SpaceX is endeavoring to build reusable rockets that will land safely on Earth after boosting their payload into space. But other innovations may face a variety of obstacles, including, “Is it legal for us to build it?” and “Is it dangerous to build it?”

Consider ABC Medical Device Company, which fabricates tools out of stainless steel. Someone at the company comes up with an amazing innovative device that’s made out of plastic. The question of “Can we build it?” may then be a matter of current operational capability. ABC Medical Device doesn’t fabricate tools out of plastic, only stainless steel; so no matter how awesome a suggestion may be for an innovative plastic instrument, it’s not getting built by ABC Medical Device.

But then again . . . Perhaps because of this suggested innovation, the leaders of ABC Medical Device should look at their business plan and consider whether expanding the business to include plastic fabrication would be a smart move. Is the market for plastic tools growing? What would it cost to enter it? Are the customers the same for stainless steel as they are for plastic? Should ABC enter into an agreement with an external plastic fabricator and sell the products under the ABC brand? These are all very good questions.

2. “Can we afford to build it?” The WebbLogic model forces you to evaluate whether your new service idea, enterprise innovation idea, or product can be built in a way that can successfully launch to a marketplace. When we think about the build corner of the model, we have to remember that there is always a need to look at price sensitivity. In other words, what the customer is willing to pay. You can build just about anything, but if the customer doesn’t value it at the price you can afford to sell it, it will fail miserably. You need to ask yourself, “Can we effectively build this innovation in a way that provides differentiated value when compared to competitive options?” Don’t just speculate about this. Verify it with experts. Get real quotes and work with real numbers. If you can’t build it in a way that exceeds customer expectations and addresses price sensitivity, you don’t have an idea.

The WebbLogic model can be adapted for use with innovations that impact processes rather than products—processes that are designed to cut costs or improve the quality of existing products and how they’re produced.

Potential

In the center, or at the very heart, of the WebbLogic triangle is Potential.

The idea may look promising now, or it may look insignificant. The real question is, “What’s its potential for growth and added value?”

Potential is the combination of the three points of the triangle: opportunity, build, and sell. Together they create potential, or lack thereof. An idea that lacks the potential to add value at a cost that will raise profits needs to be discarded. An idea that can add both value and profits deserves to be toggled through to the next section of the innovation pipeline.

The WebbLogic model can help you evaluate an innovation as well as guide you as you develop your criteria for your messy middle, where you take a closer look at eligible innovations to determine their financial and operational feasibility.

The ideas that fail the WebbLogic model get toggled out.

The ideas that show promise get toggled through.

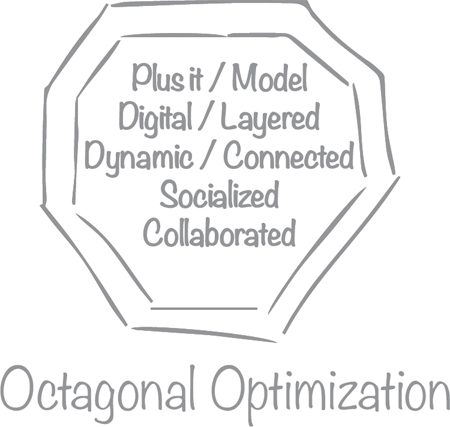

4. Octagonal Optimization

Here we advance from the general to the particular.

We take a possible innovation and put it into our business context.

We know that innovation is a numbers game: the more sparks you have, the greater chance there is that one of them will blaze brightly into a brilliant star. Most sparks will fizzle out and disappear, but that’s all right. It’s just like hiring someone to fill a key role in your company: you may receive a hundred résumés, out of which you’ll interview five candidates and ultimately hire just one. That’s one in one hundred—which is fine, and what everyone expects. It’s the way you find the best people!

Here in octagonal optimization, we strive to further clarify, identify, and strengthen those innovations that have entered the spark generator and passed through both the fast filter and the messy middle. Now we’re getting to the best of the best! But the failure rate is still very high, just like when you’re hiring for a key position. You know the old saying, “Hire slow, fire fast.” The same applies to your innovation pipeline. Slowly nurture the sparks that may burn bright. The duds? Get rid of them quickly!

Now is the time to put the new ideas to the test and see where they fit into your business and its mission. Here are the eight areas where you can significantly improve your innovations and their odds of surviving:

1. Plus it. This is a phrase made famous by Walt Disney. When one of his Imagineers came up with an idea, Disney would say, “Interesting. Now plus it!” It was his way of asking them to take an idea and see how it could be taken to the next level. Could it provide even more value? Be used in some other context? Create synergy with some other idea?

When talking about Disneyland, Disney said, “The park means a lot to me in that it’s something that will never be finished. Something that I can keep developing, keep plussing and adding to—it’s alive. It will be a live, breathing thing that will need changes. . . . I wanted something live, something that could grow, something I could keep plussing with ideas, you see?”9

2. Model it. Some of the best innovations today are not so much bright shiny objects but rather integrated business models. Can you optimize the idea by looking at the way in which you build out the commercial model? In other words, is the innovation utterly unique to your organization or even to one application, or can it be used to create value elsewhere?

It can be useful to create a minimally viable product (MVP), an early version of the product or service that envisages an interaction with a customer, stakeholder, or business process. Not only might this validate the idea, but by performing a quick initial and low-cost test you can assess what you’re doing and decide whether to toggle the idea forward or jettison it.

3. Digitize it. It seems like everything today is either digital or digitally connected. Can your innovation become part of the digital universe to improve the way in which you can deliver value to your enterprise and customer? For example, in the innovation pipeline at ABC Medical Device is a new design for a stainless-steel refrigerator for storing vaccines. What will get the idea toggled through to the next phase is the fact that it can be digitally connected to the hospital’s computer network and its inventory constantly monitored. Its compatibility with the Internet of Things (IoT) gives the design much greater value than simply being a good refrigerator.

4. Layer it. For a new product, layering value suggests that you add multiple layers of value in the way you design the packaging, warranties, and instructions. Every aspect of the innovation should have multiple layers of value; often this involves little or no cost but makes a tremendous customer impact.

Layering has become ubiquitous in the automobile industry. In the past decade, much of the innovation in auto design has been in the realm of digital services for the driver and passengers: features including mobile communications, autonomous driving, remote self-starting, and vehicle systems monitoring have turned even low-priced automobiles into enormously complex digital machines.

For an organization that provides services, layering gives a critical competitive edge. If you’re a marketing company, you may specialize in one core area, such as email marketing, but also have expertise in other areas such as SEO, website design, content marketing, or social media marketing. If a potential innovation can work across several layers, that’s a strong asset. An innovation may also involve partnering with outside consultants who possess skills complementary to what you’re offering; they can help you expand your market reach while taking some of the work off your hands.

5. Make it dynamic. If you have an Apple iPhone, then every once in a while you’ll suddenly discover that your phone has magically gotten better. The iPhone is part of an open community of iPhone app developers that are constantly creating solutions that make the user’s life easier and just plain better.

Give your technology a way to continually evolve.

But this doesn’t just refer to the product itself. Sometimes the product “is what it is,” and the dynamism comes in how you manufacture it or sell it. Earlier in the book we told the story of Febreze, the air freshener created by Proctor & Gamble. The product itself was innovative, which they thought was enough, and the company tried to sell it like any other air freshener. But consumers didn’t respond. Eventually the marketing campaign became innovative and dynamic. By taking a new approach to selling the product, sales skyrocketed.

Likewise, the Coca-Cola soft drink is the same product the company has been selling since 1886—and, in fact, consumers resist any change to the drink’s formula! To keep pace with a rapidly evolving market, the company changes how they package and sell the product. They also model it by manufacturing endless variations of the core product, including plain water, which is sold under the seemingly exotic name Dasani. In fact, Coca-Cola uses tap water from local municipal water supplies, which it then makes more palatable by filtering and adding trace minerals.10

6. Connect it. We are in a time of massive hyper-connectivity, and when anything can be connected, it will be connected; and when it’s connected it will deliver more value. How can you build out connection architecture in your design?

Nowhere is this seen better than in the way films and their interactive counterparts, video games, are marketed. The history of film and merchandising tie-ins dates back to 1925, with The Lost World. This American silent monster adventure film was released at the height of a “puzzle craze” in the United States, and plans were quickly drawn up to create marketing synergy. An innovative trailer was filmed showing cast members and the director poring over “The Lost World Puzzle,” a simple set of twelve images that you needed to fit together.11

The modern mega-tie-in template was forged in the 1990s, when director Steven Spielberg and Universal Pictures created enormous advertising and merchandising connections for his 1993 blockbuster Jurassic Park. During the pre-production phase that lasted over two years, Universal Studios inked over one hundred licensees to market over one thousand dinosaur products for the film. The big players were McDonald’s, which invested $12 million; toymaker Kenner, which paid $8 million; and video-game company Sega, which contributed $7 million. It was the grand slam home run of film merchandising, with toys, video games, and cross-promotional tie-ins with big global brands.12

Spawning four sequels in 1997, 2001, 2015, and 2018, Jurassic Park would reign atop the all-time worldwide box office for several years, earning over $900 million.

The king of movie cross-marketing? As of the time of this writing, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, with its string of action-hero films, has posted worldwide gross receipts in excess of $14 billion.13 Remember, the Marvel Cinematic Universe began in 1996 with a bankrupt comic book publishing company that made huge gambles—and won them all.14

Can an innovation in your pipeline be leveraged to create value in an unexpected way with a new connection?

7. Socialize it. Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram have become ubiquitous. We are expected to be able to engage others with our connected devices, and we like to play social games and collaborate with others. Can your innovation be socialized so as to build a community of super-happy users?

For example, sportswear giant Nike has dialed back its television commercials, and instead pours its marketing resources into the digital space. The company uses social media to create a lifestyle and sense of community among consumers. Its tweets are concise and compelling, and nearly always include the hashtag #justdoit, as well as other community-building hashtags like #nikewomen. Nike has separate Facebook and Twitter accounts for each of its product categories, including golf, snowboarding, and FuelBand, as well as two football pages—one for the American variety and one for the variety played by everyone else in the world. And they’re not just pushing product; the Nike Support feed resolves product questions and technical needs, and answers hundreds of questions per day.15

8. Make it collaborative. Never innovate in a vacuum! Find really smart people and even a few really crazy people to collaborate with you to look at an idea from many different vantage points. For example, if your innovation champion or committee is made up of people from logistics and production, they’re going to look at every idea from their perspective. There’s nothing wrong with this; it’s just human nature. They will ask themselves, “How can we make this thing?” or “Will this idea cut costs?” They may miss how an innovation could make a big difference outside their area of responsibility.

A common obstacle to unexpected innovation is a cognitive bias that psychologists call “functional fixedness,” which pioneering psychologist Karl Duncker defined as being a “mental block against using an object in a new way that is required to solve a problem.” A company’s leaders—and even its own innovation team—can’t look beyond the way they have always looked for solutions. Ironically, success makes functional fixedness more ingrained; the more success a team has had with their standard approach to a problem, the more difficult it is to embrace one that is totally new and therefore perceived to be risky.

The most well-known example of functional fixedness is Duncker’s story of the candle—which you can try yourself as a brain teaser. Participants were given a candle, a book of matches, and a small cardboard box containing a few thumbtacks. The challenge was to attach the candle to the wall and light it so the wax wouldn’t drip on the table below.

Think about it for a moment. What’s the solution?

Use the box as a candleholder by tacking it to the wall and setting the candle upright in the box.

Duncker theorized that participants who didn’t figure it out were fixated on the box’s normal function as a container for the thumbtacks and could not re-conceptualize it in a manner that allowed them to solve the problem.16

When an innovation arrives at the octagonal optimization phase, be sure to look at it with an open mind: it may have a function or value that you don’t see right away!

5. The Perfect Plan

When an idea gets toggled through to this final phase, it’s ready to be operationalized.

If it’s a product, it needs to be manufactured and marketed.

If it’s a process, it needs to be put into action.

To do this correctly requires a plan. Elements to be considered include:

• Customer engagement. If customers are directly involved, as with a product or a customer-facing process, then you need to identify them, reach them, get them excited, and get their feedback. With internal process innovations, such as an improvement to an assembly line, the “customers” are the employees impacted by the new process.

• Channel plan. You reach your customers through the paths or pipelines through which goods and services flow in one direction (from vendor to the consumer), and the payments generated by them flow in the opposite direction (from consumer to the vendor).

• Revenue and expense. You want a return on the investment you’re making in this new product or process. This applies to both selling a product and making an internal process innovation.

• Marketing and communications. You need to determine how you spend your marketing dollars and resources. Who will be responsible for the social media component?

• Digital, social, and thought leadership. Customers have opinions, as do reviewers and media partners. Increasingly, these opinions matter because anyone’s viewpoint can be posted publicly in the digital town square.

• Contingency plan. If Plan A doesn’t work the way you expected, you should have a Plan B in place that is something other than just killing the idea. This includes identifying alternative sources of funding, sourcing of raw materials, manufacturing, distribution, and marketing if the reality of the marketplace doesn’t match your projections.

• Integrated commercialization strategy. This refers to the series of financing options that you consider as you move your technology or product from concept to the marketplace. You must estimate when your product will be commercially available, when your principal competitors are likely to enter the market (if they aren’t already there), and when your target customers will become responsive to your technology or product.

THE INNOVATION PIPELINE OF XYZ CONTROLS COMPANY

Here’s a super-simplified example of how an innovation pipeline can work.

The XYZ Controls Company makes and sells digital and mechanical control systems for big office buildings—equipment like HVAC systems, fire alarms, and security systems. It’s a competitive market and the XYZ innovation pipeline is well established and productive.

Here’s a table showing the fates of eight ideas that were vacuumed up into the pipeline.

Our table will begin with phase two—the fast filter. This is because the spark generator is nonjudgmental, and all ideas are accepted.

Phase 2 |

IDEA |

EVALUATION |

TOGGLE |

1 |

Serve free lunch to employees |

We’re not Google |

No |

2 |

Sensor for room occupancy |

Possible product innovation |

Yes |

3 |

Live chat website feature |

Possible marketing innovation |

Yes |

4 |

Build another factory in Mexico |

A very big question, but worth exploring |

Yes |

5 |

Give executives stock options |

Looks too greedy |

No |

6 |

Install locks on office washrooms |

Is this really a problem? Further study is requested. |

Yes |

7 |

New material for pipes |

Possible product innovation |

Yes |

8 |

Explore nuclear fuel option |

Crazy, but worth considering |

Yes |

As you can see, eight ideas have been collected by the spark generator, and they range from the obviously interesting to ideas that are more dubious. That’s okay! This is the spark generator, and no idea is turned away. All are fed into the greedy mouth of the innovation pipeline. All are given a quick but fair evaluation.

In the fast filter, the organization’s strategic case is applied—either manually or with software; it doesn’t matter. Two ideas are rejected: free lunches and executive stock options.

Six ideas get a yes, meaning they go on to the next phase.

One idea—build another factory in Mexico—gets a “pass” because it’s not a crazy idea but it requires a long-term analysis.

Two ideas get a flat no.

On to the next phase—the messy middle. This is where the WebbLogic model is applied. To make it simple, the bottom-line question is, “Does it pass the four criteria: potential, opportunity, sell, and build?” We’ll call it POSB—yes or no.

Phase 3 |

IDEA |

EVALUATION |

TOGGLE |

2 |

Sensor for room occupancy |

POSB yes |

Yes |

3 |

Live chat website feature |

POSB yes |

Yes |

4 |

Build another factory in Mexico |

Needs further study by C-suite. |

Yes |

6 |

Install locks on washrooms |

POSB no—HR reports there is no need for it. |

No |

7 |

New material for pipes |

POSB yes |

Yes |

8 |

Explore nuclear fuel option |

We cannot build this; there’s no business case for acquiring the technology from a partner. |

No |

Here, two ideas get rejected because the innovation champion and other evaluators saw no POSB business case for toggling yes. As before, the idea of building another factory in Mexico has been toggled yes, not because it’s accepted but because it requires significant study by top leaders. There are many innovations that the innovation champion and the relevant department heads can approve unilaterally; building a new factory is not one of them!

On to Phase 4—octagonal optimization. We have four ideas left.

Phase 4 |

IDEA |

EVALUATION |

TOGGLE |

2 |

Sensor for room occupancy |

Yes, commit funds |

Yes |

3 |

Live chat website feature |

Yes, commit funds |

Yes |

4 |

Build another factory in Mexico |

Yes, fund a study |

Yes |

7 |

New material for pipes |

Modeling done—too expensive, not profitable, no business case. |

No |

Here we see that one idea—new material for pipes—has been judged not worth investing in. It’s toggled no. But the committee decides to fund a study for building another factory in Mexico, so it’s toggled yes. This does not mean it’s going to happen, only that XYZ Controls Company has decided that the idea is worth exploring.

Next comes Phase 5—the perfect plan.

Phase 5 |

IDEA |

EVALUATION |

TOGGLE |

2 |

Sensor for room occupancy |

In development |

Yes |

3 |

Live chat website feature |

In development |

Yes |

4 |

Build another factory in Mexico |

Study ongoing |

Pending |

Out of the original batch of eight ideas, two are chosen to be put into service: the new sensor that detects how many people are in a room, and the website now has a live chat feature. The study of the factory in Mexico is ongoing.

Six months later, while the innovation pipeline has released these ideas, like any other projects in the XYZ Controls Company product and process portfolios they are reviewed for their performance:

Phase 6 |

IDEA |

EVALUATION |

TOGGLE |

2 |

Sensor for room occupancy |

Developed and sold |

Yes |

3 |

Live chat website feature |

Not worth it |

No |

4 |

Build another factory in Mexico |

Study ongoing |

Decision in 12 months |

After six months, the new occupancy sensors are selling well, but the live chat feature on the website has been deemed superfluous—it turns out the clients of XYZ Controls Company don’t need it. The Mexico factory study is still ongoing, with a decision date of no later than twelve months from now.

Was this batch of ideas worth the investment in the process?

Yes! The new room occupancy sensor is adding to the company’s revenue stream. The live chat feature didn’t cost much to try, and the company learned something about its customers. And the idea of building another factory in Mexico is being closely studied.

The innovation pipeline has a simple philosophical premise: understand our business, our market, our customer, and our organizational vision so well that we know exactly the kinds of innovations we’re looking for. When you do that, you can set up an opportunity machine that can automatically screen innovations for their relevancy and move them quickly toward commercialization or deployment.

Too many organizations don’t know what they’re looking for, making it impossible to filter ideas because they can’t recognize a good one. In addition, many organizations look at innovation as a risk management function, and as we’ve stated before, when you look at it from such a perspective, no really good idea will ever make it through the pipeline.

YOUR ATTITUDE COUNTS!

The vast majority of innovation pipelines are set up and operated in order to avoid innovations and reject them because they represent risk.

It seems crazy, but it’s true.

Too many organizations are led by risk-averse people who, despite their squeamishness, are aware they need to appear to welcome new ideas. So they set up an innovation center, or have an innovation day, or install an email employee suggestion box. They’re not really interested in the fruits of these efforts. They just want to be able to put a check mark on the list of things that organizations are supposed to do to look good in the eyes of stakeholders, investors, and the public.

This is the truth: your innovation pipeline is not a risk management tool.

It’s an opportunity tool.

Will it deliver solid-gold nuggets, one after the other, like a goose laying golden eggs?

Absolutely not. As we have seen, 80 percent of the ideas coming into your spark generator will be rejected instantly. Kapow! Gone. Never to be seen again.

And of the 20 percent that pass through the fast filter, only one in ten will be accepted. The other nine will require more study. Of these, perhaps two will eventually be made operational.

So out of a grand total of one hundred ideas that enter the spark generator, perhaps three will become reality.

Does that sound bad? Really?

Think about this:

Of all the sales prospects who enter your sales funnel, how many become paying customers?

Three percent? That’s a pretty good ratio, isn’t it?

When you advertise a key job opening, do you receive one hundred applications? Two hundred? And how many finalists do you end up with? Three or four?

So what’s wrong with a 3 percent success rate in your innovation pipeline?

I’d say it’s pretty good!

CRAYOLA’S INNOVATION PIPELINE

Yes, you’re reading the headline correctly: we’re talking about the iconic manufacturer of children’s crayons.

The first Crayola crayons were offered for sale on June 10, 1903. They were made of paraffin wax and a color pigment, and, to keep little fingers clean, each was wrapped in a paper sleeve.

One hundred and fifteen years later, they’re still made exactly the same way.

At first glance, you’d think Crayola would be the last place on earth you’d find robust innovation.

You would be mistaken.

In a world of electronic toys and computer-savvy children, Crayola has shown surprising agility and imagination. It has also shown a keen awareness of its core competency. A cookie-cutter approach to innovation might have led the company to sideline its crayon business and plunge headlong into digital electronics for kids making art. But company leaders made a careful study of internal obstacles and enablers to innovation, which suggested simpler, easier, and very successful alternatives. Crayola knew it wasn’t very good at electronics, but it had deep intellectual property competencies in chemistry—which is actually how the company had first started in the late nineteenth century.

For example, the Color Wonder Mess-Free Airbrush makes it easy for kids to make airbrush pictures. The airbrush sprays out a fine mist of clear ink that comes to life on special Color Wonder Paper.

Crayola Color Escapes are designed to capitalize on the growing market for adult coloring books. It’s a good example of an innovation taking the form of identifying an untapped market (adults) and then developing a product to serve that market that is consistent with the company’s core brand image and competencies.

This is not to say that Crayola hasn’t established a presence in the digital arena. Crayola has no expertise in the digital space, but DAQRI, a Los Angeles–based provider of augmented reality (AR) services and apps, has plenty. In the innovation pipeline, sources of innovations can be internal or external. The external sources can include partnerships or licensing deals with third parties. Working with the super-innovators at DAQRI, the people at Crayola—the makers of a century-old technology—created the Crayola Color Alive Action Coloring Pages. It’s an augmented reality product that uses an app on your tablet to animate your drawing.

Here’s how it works:

You give your child a Color Alive coloring book that has line drawings of various characters, such as a dragon and a princess. The child chooses one of the drawings as she normally would—say, a dragon—and then colors it. Then, she takes a tablet into which has been loaded the free Color Alive app. She holds the tablet over the drawing, and the camera in the tablet sees the drawing of the dragon, which the child keeps in view on the screen. The app recognizes and locks in on the drawing, which now has crayon coloring, but the black lines are still visible. The software in the tablet does a computer graphic process whereby your child’s colors are added to an animated version of the dragon. On the screen of the tablet there appears an image of your child’s dragon, in three dimensions, moving and flapping its wings. Once the animated image has been generated, the child can take the tablet anywhere with her lively customized dragon on the screen.

Jeff Rogers, director of portfolio marketing for Crayola, told Consumer Goods Technology magazine, “We have always been very comfortable with creativity; we also knew we had an incredible brand and began to recognize that we could leverage it in more ways. . . . What we needed to think about in terms of innovation was not only applying it to product, but to virtually everything we do.”

That’s right on target: innovative companies don’t just think about product innovation, but about innovation in everything they do.17.