Japanese Naval Air Power as an Offensive System, 1937–1941

The first several years after the collapse of the international naval limitations in the mid-1930s, the evolution of naval aviation in all three major navies depended upon the studies, research, and exercises internal to each navy, supplemented by whatever intelligence could be gleaned regarding the tactical and technological developments of the other two. Assessments of the viability of specific aircraft, ships, weapons, and tactics of naval air war were for the most part still a matter of educated guesswork in each navy.

The general conception of the role of naval aviation in a fleet action was remarkably similar in all three navies. While each held to the primacy of the heavy surface gun as the final arbiter of naval combat, none viewed such combat as simply a replay of Jutland. Rather, all saw the future clash between capital ships as being decisively affected by the introduction of naval air power, either through damage to the enemy’s battle line (after the destruction of his air power) or through the disruption of his gunnery. The top brass in all three navies had confidence in the ability of heavily armored capital ships to withstand all but the heaviest attacks by land- or carrier-based aircraft and had doubts that carriers could long survive unprotected in a clash with battleships. Their opinions were based not on the blind obduracy of “battleship admirals” but on a range of detailed studies and practical experiments. These showed that the bomb loads of most naval aircraft were inadequate to destroy a capital ship under way and took into account the meager protective armor on aircraft carriers.

The outbreak of the war in Europe in 1939, and the active involvement of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm in the subsequent naval combat in the North Sea, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean, seemed to promise a more realistic gauge against which to measure the validity of such speculation. Yet if the first two years of the war failed to confirm the primacy of the capital ship, they hardly confirmed that the aircraft carrier had taken its place. Within the first eight months of the war, the Royal Navy had lost two of its carriers—one to the guns of capital ships—with only the destruction of a German light cruiser to show for it. While it is true that during the next year, British carrier aircraft sank three battleships (French and Italian) and damaged two others, all were in port and at anchor. Indeed, the first dramatic sinking of a capital ship under way in which naval aircraft played a significant role did not occur until the spring of 1941, with the sinking of the German Bismarck. She was crippled by British carrier-borne torpedo bombers, and they demonstrated that she could not operate in the face of enemy air superiority, but her actual destruction was wrought by heavy British surface units.

Moreover, with one exception—the British attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, November 1940—the nature of the conflict waged by the Royal Navy during 1939–41 seemed to have limited relevance for Japan as its naval high command contemplated possible conflict with the United States. To begin with, neither of Britain’s enemies in those years, Germany and Italy, possessed a carrier force that posed a threat to the British fleet or Britain’s naval facilities. The Royal Navy thus lacked the tactical or technological impetus to develop carrier warfare. Also, hampered by budgetary limitations and struggling with the Royal Air Force over the control of naval aviation, the Royal Navy was bound to lag somewhat behind the Japanese and American navies in developing carrier forces, particularly carrier aircraft. Finally, the nature of naval operations in the Atlantic provided little opportunity to develop carrier warfare. The range of uses to which the Royal Navy was obliged to put its carrier forces—tracking and destroying enemy surface raiders, providing convoy escort, ferrying land-based aircraft to critical combat theaters, and the like—seemed to have little relevance to the Japanese navy. As the Japanese had given scant thought to trade protection, the attention the Royal Navy devoted to escort carriers, catapult-armed merchantmen, and other innovations stirred little interest on the part of the Japanese Navy General Staff. For the Japanese navy, the guiding objective that drove the training of its aircrews, the development of the aircraft they were to fly, the design of the carriers from which those aircraft were to operate, and the positions those carriers were to take in any fleet action remained the midocean destruction of the U.S. carrier forces and battle fleet.

THE PROMISE AND PERILS OF JAPANESE NAVAL AIR TRAINING

We have seen how the China War proved to be instrumental in furthering the tactical confidence and developing the tactical doctrines of the Japanese naval air service, as well as in increasing the number of its operational units. But the expansion of the service and an effort to upgrade the qualifications of its personnel had begun even before the China conflict erupted. In May 1937, in order to increase the caliber of navy pilots, particularly those who would be section leaders, the Flight Reserve Enlisted Trainee (Yokaren) course system was expanded to place an emphasis on the recruitment of youngsters who had the equivalent of a U.S. high-school education, not just middle-school education, as before.1 This latest training category enabled the Japanese naval air service to draw upon a new pool of young men who could be more rapidly trained. It complemented the older sources of pilot recruits: the small number of Naval Academy graduates who volunteered for flight training; the slightly larger number of pilot trainees drawn from enlisted ratings under twenty-four years of age (who might reach the rank of warrant officer or special-duty ensign or lieutenant, junior grade); and the large number of candidates drawn directly from civilian life into the original Yokaren program. This expanding system of pilot procurement further enforced the tendency for fliers in the Japanese navy to be enlisted men rather than officers.

But the very high ratio of enlisted men in the cockpits of Japanese naval aircraft—about 90 percent—was not only the result of the recruiting avenues that had been established. It was also due to the particular conditions of Japanese naval aviation and to the navy’s promotion system. During the years when the greater portion of Japanese naval aviation was carrier-based, there was little incentive for junior officers to volunteer for flight training. Future command prospects for naval aviators were limited.

Junior officers in the naval air service could not count on their pilot training as a ticket to rapid advancement, in part because of the rigid seniority system of the Japanese navy, and in part because carrier and air group commands were not limited to those officers who were naval aviators. Thus, as late as the Pacific War most of these commands were held by naval officers who were not air-qualified, because there were too few pilots of sufficient seniority to occupy them. On its part, the United States Navy dealt effectively with this problem in two ways: first, by making it the rule that all such commands could be held only by aviators; and second, by giving a number of nonaviator senior officers sufficient flight training to qualify them for these aviation commands.2 The rapid expansion of the land-based component of the Japanese navy’s air arm during the China War to some extent opened up the prospects for naval aviators to assume aviation commands, and admittedly, three of the six carrier captains in the Pearl Harbor operation had gone through flight training at Kasumigaura. Yet the generally lesser influence of Japanese naval aviators over the conduct of operations in their own service was to have important repercussions on a number of occasions during the Pacific War.3

Initially, all basic flight training was conducted at the Yokosuka Naval Air Base, but in the late 1930s it was moved to Tsuchiura, where in November 1940 a training air group was established to carry out this function. As the navy expanded its recruitment for the Yokaren courses, other training air groups up and down the Japanese home islands were established to handle the increase in personnel.4 After graduating from these units with approximately three hundred hours’ flying time, future fighter pilots were sent on for further training at one of three operational air groups: Ōmura or Ōita on Kyūshū, or Tokushima on Shikoku. There they mastered carrier flight operations, acrobatics, formation flying, and air combat maneuvers. After this, they were posted to combat units, either to a carrier or to a land-based air group for another year of intensive training. The best pilots, with an average of about eight hundred flying hours, were attached to carriers. Squadron commanders had even more experience.5

Not all aviators were trained to fly fighter planes, of course. A program for Special Flight Training Students (Tokushūka Kōkūjutsu Renshūsei) was revived in November 1938 to provide nine months of intensive instruction in bombing, observation, and communications, particularly for those officers who would be assigned to bombers. The training of these student candidates in horizontal bombardment was to be particularly important, since the greatly increased accuracy they achieved in practice (against stationary targets) was to be of prime importance in the opening hours of the Pacific War. No less important was the training, given to certain land-based naval air groups, in aerial torpedo attacks on warships under way. Here too the training was to pay off thunderously at the outset of the war. The Japanese navy was far more assiduous in training navigators, bombardiers, and gunners than the army, and by 1941 its training units had turned out some twenty-five hundred such aircrews.6

A particular feature of advanced Japanese naval air training in the interwar period was a tactical training process called sengi. “Combat skills” comes perhaps closest to an English translation of the word, and it referred to a series of tests undergone by individual aircrews and judged by fellow fliers. Established in the 1920s but not made official until the mid-1930s, it was holistic in that it included training not just in aerial tactics but also in leadership, aircraft maintenance, communications, and various other elements that contributed to successful air combat, and for this reason the training included not just aircrews but also ground crews. It was both a top-down and a bottom-up system in that it was the product of intense interaction between the Naval Aviation Department (which controlled all naval air training, not the Naval Education Department, as was the case for the rest of the navy) and the actual air groups (which were the actual training units). It thus integrated the practical experience of the navy’s aviators—and, during the China air war, the results of actual air combat—with the wider-ranging perspectives of headquarters. For that reason sengi training allowed an unusual amount of input from junior officers. Normally, after annual training exercises in the Japanese navy, there would be a postexercise review at which a few senior officers would speak, following which the meeting would be concluded. But in the Japanese naval air service, the views of the junior officers who had the most active role in the exercise would be sought out. In this way, a thorough airing was given to innovations across a wide spectrum of practical issues: fleet air defense, air-to-ship radio communications, night air combat, quick landing and storage aboard carriers, and related matters.7

There is little doubt that sengi training contributed significantly to the combat proficiency of Japanese naval air groups in the decade before the war. But Japanese naval air training faced impediments, both internal and external. One problem was that, like many bureaucratic initiatives, sengi training tended, in the years immediately prior to the war, to become formalized and routinized and thus lost some of its earlier spontaneity and ability to challenge accepted doctrine. As it did so, there was an increasing tendency, particularly among the navy’s fighter pilots, to ignore some of the more important tactical principles it had established, such as formation flying and combat, and to revert to their predilection for the individual heroics of dogfighting.8

But Japanese naval air training also faced the ongoing shortage of naval fuels that had confronted the Japanese navy since its switch from coal to oil after World War I. Training in carrier flight operations in particular suffered from this deficiency. Carriers steamed at high speeds to provide the wind-over-deck needed to get aircraft aloft, and in the process they consumed huge amounts of oil. The First Carrier Division, long the core of the navy’s carrier forces, always exceeded its fuel allotment in training and was thus resented by other fleet elements. For this reason, aircraft were generally sent ashore for general flight training and for both bombing and torpedo practice. Training in carrier flight operations was thus undoubtedly more restricted than in the United States Navy, which had abundant petroleum stocks.9

The Japanese naval air service’s most marked difference from its American counterpart was that up to the last year or so before the Pacific War, it had no concept of mass training for its pilots, largely because of the Japanese navy’s obsession with quality over quantity. The navy’s most internationally known fighter ace to survive the war, Sakai Saburō,† was to recall in his memoirs that pilot training in the 1930s was selective in the extreme: only the most physically and academically qualified young men in the entire nation could hope to be considered for basic flight training. (Sakai himself was one of seventy trainees selected from more than fifteen hundred applicants.) Once selected, students in the seven to nine months of naval flight training—increased to a year after 1940—faced a ferocious test of physical and mental skill. Sakai recalled that his training at Tsuchiura was a constant and exhausting series of demands on the body and mind: obstacle courses, diving, acrobatics for balance and muscular coordination, exercises to develop peripheral vision, and tests to speed reaction time. “During the 1930s,” Sakai wrote, “the Japanese Navy trained approximately one hundred fliers a year. The rigid screening and expulsion practices reduced the many hundreds of qualified students to the ridiculously low total of a hundred or fewer graduated pilots.”10 Those few who mastered these rigorous challenges proceeded to advanced training with carrier- or land-based air groups, and from there to combat with operational units in China. By 1941, in training and experience, the navy’s fighter pilots as a whole were among the best in the world, and its carrier pilots were probably the best among the world’s three leading carrier forces. But there was a fundamental defect in the rigorous training program, a defect that stemmed from the navy’s basic assumption concerning the nature of a U.S.-Japanese conflict and the conviction that quality was more important than quantity. On the basis of these two premises, the Japanese navy had adopted a training program that produced a much smaller pool of aviators than its American counterpart.

Different assumptions concerning the length of a U.S.-Japanese war and a consequent difference in aircrew training policies in the immediate prewar years were fundamental to this quantitative discrepancy. The Japanese gambled on the clash being brief and therefore placed priority on having at hand a small core of superb aircrews who, flying superior aircraft with superior skill, could decimate their enemy counterparts in a lightning conflict. For that reason, in December 1941 there were just a little over five hundred Japanese naval aircraft dedicated to training purposes. While the navy issued a plan in 1941 for the training of some fifteen thousand pilots annually, the war overtook this effort to build an adequate reserve of qualified aircrews. The navy was thus forced to enter the war with only its cadre of first-line pilots. Should attrition in combat take its toll, there would be no reserve of trained airmen to take the place of those who were lost.11

The assumptions and policies of the United States Navy were quite different. Convinced that any conflict with Japan would be prolonged, it gave priority to building up a large reserve of qualified aircrews. Some three years before the Pacific War, the United States Navy made a basic decision to expand pilot training and the production of training aircraft, even if, at the time, this meant limiting the number of combat aircraft and personnel in operational air units.12 Thus, on the eve of the Pacific War the number of proficient pilots in the United States Navy constituted a relatively large pool of about eight thousand or so. In contrast, while the annual number of graduated pilots increased substantially as the Pacific War approached, in late 1941 the Japanese navy had on hand probably not much more than nine hundred outstanding pilots—mostly on carriers—out of a total pilot pool of around thirty-five hundred.13

EVOLUTION OF JAPANESE FIGHTER TACTICS

But the consequences of these flaws in Japanese naval air training lay in the future. In the four years between the end of the treaty era and the outbreak of the Pacific War, that training, combined with the experience of air combat over China and the accelerated efforts to prepare for the possibility of air and surface operations against the United States Navy, intensified the development of the Japanese navy’s air combat tactics.14

It was during the China War, as we have seen, that the navy’s fighter and bomber squadrons perfected the basic tactical formation, the three-aircraft shōtai composed of a leader and two wingmen.15 When not actually engaged, the three aircraft usually formed an equilateral triangle with about a 50-meter (160-foot) interval between the section leader and his wingmen with all three flying at the same altitude. When anticipating combat, Japanese navy pilots usually adopted a looser formation, with much greater intervals between the section leader and the wingmen in order to provide for greater flexibility. Often this formation took the shape of a rough scalene triangle (much like the United States Navy’s A-B-C formation), with one aircraft trailing the leader at about 200 meters (650 feet) higher altitude and the third flying about 300 meters (1,000 feet) higher than the leader to provide top cover.16 (Fig. 6-1.) From this basic formation a section leader could deploy his aircraft into a line astern for successive firing passes against a target or into a line abreast in order to box a target in with alternate passes from each of the two wingmen while he remained above and astern for protective cover.

Success for these formation tactics in the wild chaos of combat required an aircraft of exceptional maneuverability, which the navy had in the Mitsubishi Zero, and pilots of consummate skill whose teamwork was the result of hours of relentless training and practice. The coherence of the shōtai formation and the impressive gunnery runs achieved by the navy pilots who maintained it in the midst of the most violent aerial acrobatics are testimony that in the years immediately prior to the Pacific War, the navy’s fighter squadrons were composed of highly disciplined aviators and enjoyed high unit cohesion. Their coordinated hit-and-run tactics took them away from their natural inclination for dogfighting, in which pilots clung tenaciously, if unimaginatively, to the tail of an enemy aircraft. Indeed, so familiar with each other’s combat tactics were the fliers in a three-man shōtai that some navy pilots claimed to have developed an almost sixth sense (ishin denshin) by which they could communicate with their two comrades flying with them. Apparently this coordination of thought and action could sometimes be extended to the nine-man chūtai (a vee of three shōtai), but in air combat involving really large formations, such as the eighteen-man daitai, it was impossible to maintain such tight control.17 (Fig. 6-1.)

Postwar interviews with surviving Japanese navy pilots have indicated that such mental telepathy did exist. On the other hand, famed pilot Sakai Saburō recalled that he saw very little of such empathy between officer and noncommissioned officer pilots because of the strict status distinction between the two. It is possible that this telepathic sense existed at the opening of the war even between noncom and officer fighter pilots who had trained constantly together in a cohesive unit, only to be lost later on under the impact of attrition and the constant replacement of pilots.18

In any event, this nearly automatic pilot-to-pilot coordination, if it existed, depended upon pilots of long training and experience. Tactical control of aircrews of less elite status would be more dependent upon airborne radio communications. Here it must be noted that air-to-air and air-to-ground communications were a problem for the air services of all nations during these years. Crystal-controlled equipment—which comprised all four types of radio sets in the Japanese navy—operated at only a few frequencies, though it maintained those frequencies accurately. Analog-tuned equipment, on the other hand, covered relatively broad frequency bands but drifted because of vibration and the idiosyncrasies of electronics. Japanese radio (as distinct from radar) appears to have been nearly the equal in performance of U.S. equipment prior to the Pacific War. Eventually, of course, the enormous effort the United States put into electronics, developing superior radio equipment at an unprecedented rate and supplying it promptly to American combat forces, proved impossible for the Japanese to match.19

Fig. 6-1. Tactical formations for Japanese navy fighters

In the late 1920s the Japanese navy had begun the first serious attempts to develop radio communications in its aircraft, an effort accelerated by the unfortunate incident of the 1929 annual naval maneuvers, when several aircraft from the Akagi were lost in bad weather because they could not communicate with the carrier.20 That same year the first Japanese-designed radio equipment was produced, and a communications section and a communications officer were added to each air group. But the greatest difficulties in transmission among the radio devices placed aboard Japanese naval aircraft in these years were posed by radio telephone systems. Radio telegraph (using Morse code) existed and was used effectively in bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, but it was obviously impractical for communication between fighter aircraft engaged in split-second combat maneuvers. The Japanese Type 96 radio telephone was developed in 1936 but was not installed in Japanese naval aircraft until early in the Pacific War. The quality of shipborne radio telephones was adequate, but at this stage of Japanese radio technology, comparable quality was not available in airborne systems: transmission was too often obscured by interference and static, and reception of voices was therefore too often fuzzy.21 It was for these reasons that fighter pilots usually had to rely on a variety of visual signals: wagging the wings, hand semaphores, prearranged signal flares, or on such mental-telepathic communication as appeared possible after months of intensive practice and training.

On the eve of the Pacific War, Gordon Prange tells us, radio communications were a serious problem for those planning the Pearl Harbor operation, since only radio telegraph would carry the 250–300–mile distance from the carriers to the target. For that reason, the pilots participating in the operation, including the fighter pilots, had to master Morse code in the months previous to the attack. For much of the Pacific War, this communications handicap, in combination with the lag in Japanese development of an effective radar system, was to pose a critical disadvantage for Japanese fighter units.22

Yet it is clear that in the years 1937–41 the aircraft and pilots of the navy’s fighter squadrons had come into their own, both defensively and offensively. Great hopes were placed on the Zero’s 20-millimeter cannon for protecting the navy’s ships and bases from enemy bombers. The latter were to be opposed by fighter formations that would concentrate, if possible, on the lead bomber. To cover its carriers, the Combined Fleet devised an elaborate system of fighter patrols (discussed below).23 But though fighter aircraft now comprised the core element in fleet air defense, their place in the navy’s growing offensive power was even more valued. While the idea of using fighters as bombers had not proved to be practical, the China War had demonstrated that the range and firepower of the Zero appeared to make it a formidable adjunct to any bombing force the navy could assemble. This belief was apparently confirmed by the success achieved by Zero fighters in the first offensive operations of the Pacific War. Indeed, it can be argued that after the Japanese air victories over Pearl Harbor, Port Darwin, Colombo, and Trincomalee, the Japanese navy’s estimation of the value of fighter aircraft in a primarily offensive role became seriously exaggerated. In this view, the insistence of Japanese air officers—Genda Minoru among them—that the bulk of the Midway task force fighter aircraft be used as escorts for bombers against Midway Island, rather than for the maintenance of an adequate combat air patrol (CAP) over the Japanese carriers, was a decision that contributed to the ultimate Japanese disaster in that campaign.24

COMING OF AGE

The Navy’s Air Attack Tactics

Of the navy’s various methods of aerial bombardment, it was horizontal bombing that was given the most extensive trial during the China War. The navy’s long-range high-altitude bombing missions over China gave its air units useful experience in various aspects of such operations, but given their emphasis on saturation bombing, they did little to improve the bombing accuracy of the navy’s land-based bomber groups. At the same time, from its studies on the possible effects of the high-altitude horizontal bombing of maritime targets, the navy expected that it would be difficult to destroy a heavily armored capital ship by a few aircraft carrying small bombs. Only large bombs dropped by numerous aircraft had any real chance of success, the navy believed. Indeed, its research on the subject led the navy to conclude that use of the largest available ordnance, if modified (see below) and if dropped from a high altitude, could penetrate warship armor and thus accelerate the destruction of enemy surface units. But the problems seemed insurmountable: there were too few aircrews sufficiently skilled to attempt attacks against ships under way; moreover, the navy’s medium bombers could carry only one 800-kilogram (1,764-pound) bomb. Thus, from its bombing experiments at sea and from its actual bombing campaigns in China, the Japanese navy came to recognize a frustrating paradox. On the one hand, hits against a target at sea were far more likely to result in the permanent elimination of that target—its sinking—than hits directed against an air base or city quarter, which could often be repaired or reconstructed. On the other hand, the destruction of a moving target at sea by high-level bombing was much more difficult, if not impossible, to accomplish.25

By 1941, therefore, the navy’s experiments in high-level horizontal bombing were so discouraging that it was on the verge of abandoning the effort entirely and relying instead on torpedo and dive-bombing tactics.26 It was an accepted belief that in a surface engagement, twelve to sixteen direct hits from the largest shells could destroy any warship afloat. While it would require the total striking power of six Akagi-class carriers to accomplish the same result by high-level bombardment, it was held that the same number of torpedo bombers could probably sink more than ten capital ships.27 But in planning the Pearl Harbor strike the Japanese navy concluded that it could not rely on torpedo attacks or dive bombing by themselves. As Gordon Prange has recounted in his study of that operation, the Japanese assumed that not only would any battleships anchored next to Ford Island be protected by torpedo nets, but the standard American double mooring of warships would mean that only the outer battleships would be vulnerable to torpedo attack. Moreover, the lighter ordnance carried by the Japanese carrier dive bombers could not be expected to do fatal damage to the heavily armored decks of the U.S. battleships.28 Thus, horizontal bombardment was left as the only means of dealing with the “battleship row” at Pearl Harbor. But the navy’s efforts in horizontal bombing had proved a major disappointment for most of the 1930s.

By his own account, at least, it appears to have been Lt. Okumiya Masatake, an instructor at the Yokosuka Naval Air Base, 1938–39, who first suggested one of the means to improve the accuracy of the navy’s horizontal bombardment. After arriving at Yokosuka in 1938, Okumiya made a careful study of basic flight-school test scores. He concluded that the fundamental problem was one of aptitude. There were many good pilots in the navy, but few good bombardiers, largely because the best graduates of flight school became fighter or attack aircraft pilots. Because they were not trained as bombardiers, attack aircraft pilots simply became drivers, with bombardiers sitting in the back seat. Okumiya argued that some of the best pilot graduates of flight school should be given intensive bombardier training and then teamed up with the most skillful bombardiers in a permanent unit, working together until they functioned almost as one man. Okumiya’s proposals were soon taken up by the navy, and at his recommendation, Ens. Furukawa Izumi, one of the best pilots in the Yokosuka Air Group, was given special training in horizontal bombardment. It was Furukawa who then became a central figure among the navy’s bombing experts and, as a member of the Akagi’s attack squadron, took the lead in training carrier aircrews in horizontal bombardment. With energy and determination, Furukawa molded the Akagi’s Nakajima B5N bomber crews into a precision instrument.29

The next step to improve horizontal bombing was to reduce the drop altitude for such operations from 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) to 3,000 meters (10,000 feet). This was the minimum height from which armor-piercing bombs could develop sufficient momentum to penetrate deck armor (though the planes risked more intense antiaircraft fire in bombing from this altitude). That having been decided, a new bombing formation was developed, which was smaller and thus concentrated more bombing units against a target. These efforts led to an improvement in accuracy from 10 percent to 33 percent and later, after further intensive practice at Kagoshima in the summer of 1941, to even better results.30

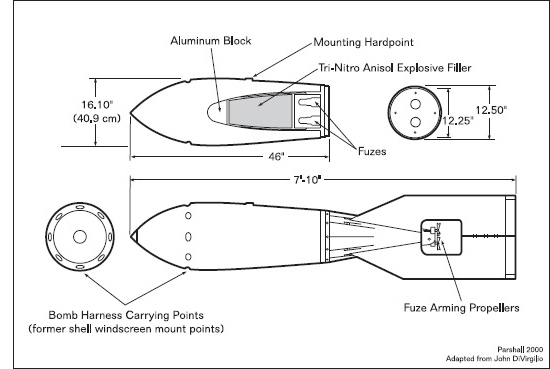

The solution to the particular problems posed by the U.S. battleship anchorage at Pearl Harbor was to modify the available ordnance to be used. On the eve of the Pacific War, the Japanese navy had three types of bombs in its inventory: a 250-kilogram, a 500-kilogram, and an 800-kilogram (551-, 1,103-, and 1,764-pound) bomb. Only the last of these, the Type 99, was suitable for use against the armored decks of capital ships. The Type 99 was actually an AP naval shell, which the navy now decided to convert by equipping it with an aluminum shock-absorbing plug placed ahead of the charge to protect it from impact detonation, so that the shell would explode after penetration, not upon impact. (Fig. 6-2.) The navy’s ordnance experts judged that it would be able to penetrate 15 centimeters (5.9 inches) of horizontal armor, which was the thickest deck protection of even the newest battleships.31

In the attack on moored warships at Pearl Harbor, the improved tactics and technology in Japanese horizontal bombing were to pay off thunderously. The most dramatic hit, of course, was scored on the battleship Arizona by a Type 99 bomb, which in striking alongside the ship’s no. 2 turret caused the massive explosion—made famous by motion-picture film footage—that instantly destroyed her.32 Though horizontal bombing was used frequently later by both the Japanese and American navies in the Pacific War, it never again achieved such success, and in any event no major surface unit under way was ever sunk during World War II by high-altitude horizontal bombardment.

While dive bombers had been used with some effect by the navy in the latter stages of the China War, particularly against communication routes in southern China, as a whole, dive-bombing techniques were not noticeably advanced by that conflict. Except for roads and bridges, the navy’s targets in China did not call for the same sort of pinpoint accuracy necessary to attack a warship under way. Thus, it was largely in naval exercises and practice runs at sea during these years that the navy’s dive-bomber crews perfected their skills. Building on experiments in the mid-1930s that combined dive bombers for the attack and carrier fighters for top cover, and exploiting the advanced capabilities of the Aichi D3A dive bomber, the navy began to work out a powerful formula for surprise attack on enemy fleet units.33

Perfected by Lt. Takahashi Sadamu† in 1940–41, the tactic called for the dive bombers to approach on a course opposite to the target, in one of a number of possible formations, beginning their attack at an altitude of probably 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) and about 20–30 nautical miles from the target. At that point, forming in echelon, the bombing aircraft would go into a shallow dive of about 10 degrees at full throttle. In succession, the aircraft would plunge in a dive of about 65 degrees, aiming at a point in advance of the target’s intended course and releasing their bombs at a height of 600 meters (2,000 feet) above the target.34 After releasing its payload at the bottom of its dive, each aircraft would retract its air brakes, pull sharply up, and, at low altitude, use all possible speed to avoid antiaircraft fire and get away. In certain circumstances the lead dive bombers were to be sacrificed in an attempt to suppress such fire with their own bombs. The navy anticipated that losses would be severe among dive-bombing squadrons in such operations. During the Pacific War the navy estimated that to make five or six direct hits on a major ship, eighteen planes would be required, of which eight would probably be shot down.35

Fig. 6-2. Schematic of Type 99 Model 80 heavy armor-piercing bomb

Japanese dive-bombing doctrine called for bombing runs to be made from either the bow or the stern (with bow-on attacks the most preferred) if the wind was negligible, but if the wind speed was greater than 15 meters per second (30 knots), standard procedure (during the Pacific War, at least) called for the dive to be made with the wind at the tail of the plane in order to minimize wind drift errors. When several dive-bombing formations attacked at once, they would come in from different directions. (Fig. 6-3.)36

Repeated practice in these techniques in the years before the war gradually improved the percentage of hits in bombing runs. In the Combined Fleet exercises of 1939, navy dive bombers of several types achieved a 53.7 percentage of hits; and two years later, in the First Fleet training exercises, using Aichi D3A aircraft exclusively, dive-bombing units attained a high of 55 percent. By 1940, therefore, the navy had adopted the Takahashi tactic as its standard dive-bombing practice. In the first year of the Pacific War it achieved dramatic results: the sinking in the Indian Ocean of the British cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire—on which 90 percent of the bombs struck home—and the small carrier Hermes in April 1942.37

The Japanese navy had traditionally considered the torpedo the most lethal weapon for use against ships, and during the interwar years it conducted an extensive torpedo research program. By the beginning of the Pacific War, therefore, the navy was armed with powerful torpedoes of unrivaled speed and range. The configuration of the Type 91 aerial torpedo, when it was first developed in 1931, had enabled the navy’s torpedo bombers to launch from a height of 100 meters (330 feet) while maintaining an airspeed of 100 knots.38 For lack of targets, torpedo bombing was the one aerial assault tactic that played no part in the China War. Through constant practice at sea and the acquisition of larger and more powerful aircraft, however, the navy was able to improve upon the performance of its torpedo bomber units. By 1937, navy torpedo bombers were able to release their torpedoes at heights of up to 200 meters (660 feet) and speeds of up to 120 knots. By 1938, Japanese tactical doctrine called for releasing them at approximately 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) from the target. Advances were also made in massed attack, and beginning in 1939, the Combined Fleet undertook research and training to coordinate carrier- and land-based torpedo operations. By that year too, night torpedo attacks, first attempted in 1934, were being carried out behind flare-dropping pathfinder units. Given these advances, to some navy men it seemed as if aerial torpedo operations were irresistible.39

Fig. 6-3. Japanese navy aerial attack methods

On the other hand, real problems remained. To begin with, there was the question of shipboard antiaircraft fire. Many held the view that in an actual combat situation, defensive fire, particularly from battleships, would be so intense that the hit ratios would be only one-third of those achieved in peacetime training and that, conversely, losses among air attack units would be unacceptably high. Under these conditions it was an open question whether such tactics were worth the sacrifices involved, and whether aerial torpedo attacks should therefore be abandoned altogether. Furthermore, the Combined Fleet exercises that attempted to coordinate attacks by carrier- and land-based torpedo aircraft soon created dangerous complications. The hair-raising proximity of attacking bombers crowded into a relatively confined air space, all trying to get in a hit while taking evasive action from antiaircraft fire, demonstrated the extreme danger of midair collisions unless some restrictions were imposed on target approaches. This led to instructions that torpedoes were to be dropped from greater heights and distances, which in turn provoked a heated controversy over the future of aerial torpedo tactics. Some, particularly in the Yokosuka Air Group, complained that the new safety limitations meant that torpedoes would be launched at such a distance that even the smallest miscalculations in aim would cause the torpedo to miss the target. Moreover, the distant-launching doctrine violated the nikuhaku-hitchū (“press closely, strike home”) tradition of the Japanese navy, hallowed ever since the small-craft surface actions of the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95.40

Ultimately, the adoption of the improved Type 91 aerial torpedo and certain changes in tactical formations improved the hit percentages and reduced the hazards in training. The matter of losses to defensive fire remained a nagging worry, however. In any event, the safety limitations seem to have remained in force, since the standard approach for the navy’s torpedo planes by the time of the Pacific War was at an altitude of between 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) and 3,000 meters (9,800) feet, depending upon atmospheric and target conditions. The torpedo squadrons, usually running on an opposite course to the target, would often divide some 10-12 nautical miles from the target, approaching it from two sides. (Fig. 6-3.) As in Japanese dive-bombing doctrine, the final run was generally made in a loose string (or in a line abreast if facing intense antiaircraft fire). The aircraft would then drop their torpedoes at an altitude of 50–100 meters (160–330 feet), some 800–1,200 meters (2,600–4,000 feet) from the target, at an airspeed of 140–162 knots.41 In this way the torpedo aircraft would carry out a “hammer and anvil” attack: no matter which direction the target turned, it would always present a broadside to one group of attackers.

Before turning to the relationship of all these offensive schemes to the development of Japanese carrier doctrine in the last years before the Pacific War, I should mention one other aerial torpedo tactic that was to play a decisive role in the opening hours of that conflict: the shallow-water attack.

Much is made of the fact that the perfection of shallow-water attack was an important part of the preparations of the Combined Fleet in the summer and autumn of 1941 for the Pearl Harbor operation, and of the fact that the inspiration for the tactic derived from the example of the British attack on Italian fleet units at Taranto in November 1940.42 In fact, consideration of shallow-water attack had begun as early as 1939, and not with Pearl Harbor specifically in mind. In that year, during the fleet’s annual exercises, torpedo planes dispatched from Yokosuka had “attacked” warships anchored in the shallow waters of Saeki Bay, Kyūshū. Because the shallow depth defeated an otherwise well-executed attempt, the navy determined to study the problem, largely at the initiative of Lt. Comdr. Aikō Fumio,† the chief torpedo instructor of the Yokosuka Air Group. That autumn, Aikō begun studying naval charts of Manila, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Vladivostok, as well as Pearl Harbor, all of which were found to have an average depth of 15–25 meters (50–80 feet). To be effective in attacking anchored ships in such circumstances, Aikō realized, an air-launched torpedo could not be allowed to dive more than 12 meters (39 feet) below the surface, a requirement that would demand a change in tactics and, even more important, some difficult and innovative changes in torpedo design. Aikō worked on the problem for some time, and while he himself did not solve it, he made a major contribution to an understanding of its parameters in a report to the Naval Aviation Department that incorporated his research as well as the navy’s experience in torpedo attacks.43

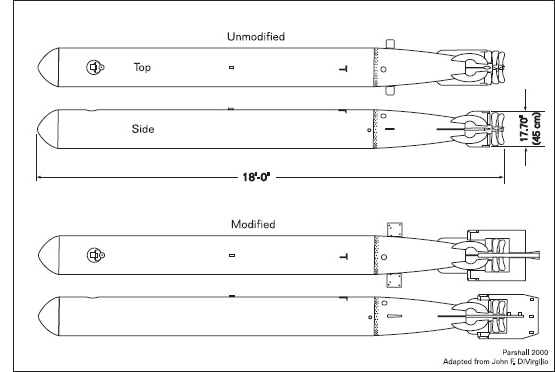

As was explained in chapter 2, the problems of impact forces breaking or deforming the hull of an aerial torpedo had been solved by the early 1930s. But good performance for a torpedo launched from the air required different fluid dynamic configurations for air and water flight. The difficulties of pitch and yaw during air flight were solved, as they were somewhat later by the United States Navy, by the addition of frangible wooden extensions to the fins at the rear tail assembly. A solution to the roll problem had been attempted by affixing small steel gyro-controlled contrarotating fins (sometimes called flippers) to the torpedo at the forward end of the tail cone. The initial attempts used fins that were inadequate to control roll during air flight. Yet larger fins would have degraded the subsurface performance of the weapon. The solution, reached in 1941, was, again, the addition of frangible wooden extensions to the fins that would break off upon the torpedo’s entry into the water and thus leave the clean configuration necessary for the hydrodynamic performance of the weapon. (Fig. 6-4.)44

Fig. 6-4. Type 91 aerial torpedoes for normal and shallow-water use

As the last technological problems of aerial torpedoes were being overcome, the tactical aspects of shallow-water torpedo attack were studied and practiced by the torpedo squadron of the Yokosuka Air Group under the leadership of Lt. Comdr. Murata Shigeharu,† the navy’s leading aerial torpedo specialist. When he became commander of the Akagi’s torpedo squadron in the summer of 1941, Murata led the development of shallow-water attack in the First Air Fleet, then being readied for war. During the autumn of 1941 Murata took his torpedo pilots to Kyūshū to practice over the shallow waters of Kagoshima Bay. Over the next four months, experimenting with various speeds, approaches, drop heights, and torpedo configurations, Murata and his pilots perfected the torpedo weapons and tactics that so stunningly opened the Pacific War.45

But carrier torpedo bombers were not the only aircraft employed in perfecting the navy’s proficiency in aerial torpedo attacks. In the years immediately prior to the Pacific War, certain land-based air groups equipped with twin-engined bombers began aerial torpedo training. One of these was the Kanoya Air Group, whose G3Ms had participated in the opening of the air war over China. In the years that followed, this unit usually undertook bombing missions over China during the summer months, but from December through April it participated in the annual exercises of the Combined Fleet, practicing torpedo runs against surface units. In particular, it practiced torpedo drops against ships steaming at high speed and, in theory, defended by fighter cover. By late 1941, relentless training by the Kanoya Air Group, now newly equipped with G4Ms, had made it a formidable weapon for use against enemy surface units.46

By 1939 the Japanese navy had begun to devote a good deal of study and practice to melding all the air attack systems discussed here—horizontal bombing, dive bombing, torpedo bombing, and fighter attacks—into a single system of massed aerial assault.47 In part the idea stemmed from the conclusion that surface targets under way and taking evasive action would be far harder to hit by a single type of air attack than by a combination of different types. By adroit handling, for example, a warship under attack might be able to comb the wakes of a number of torpedoes launched from one direction, but a simultaneous attack from another quarter would greatly reduce the chance of successful evasion, and an air assault that combined attacks by both torpedo bombers and dive bombers would make it difficult for the target to avoid being hit.

Out of the research devoted to the problem of coordinating massed air attacks by carrier aircraft there emerged an air doctrine that called for closely phased operations by various types of aircraft. In the scheme that the navy began to work out, the attack would be launched about 200 miles from the enemy. As it approached the target, the strike force, organized into vanguard and rear elements, would divide. Some fighters would provide direct cover for the attack groups racing in to hit their targets from predetermined altitudes. Others would sweep the enemy’s combat air patrols from the sky. Still others would strafe the bridges and decks of enemy carriers, an idea that derived from the experience of navy fighter pilots in ground attacks in China. The fighters would have barely swept past when high-level horizontal bombing attacks would be delivered from a 3,000–4,000-meter (10,000–13,000-foot) altitude, to be immediately followed by dive-bombing sorties that would be launched from about 3,000 meters, the dive bombers racing down at angles of 50–70 degrees and releasing their bombs about 500 meters (1,600 feet) above their targets. Almost simultaneously, a succession of torpedo attacks would be delivered, presumably 50–100 meters (160–330 feet) above the waves.48

The conduct of an operation of such complexity, precision timing, and risk required an expanded tactical organization, meticulous planning, rigorous training, skilled aircrews, and bold leadership to keep it from suffering a series of disastrous miscues. All of these ingredients were essential, of course, to the preparations for the single greatest occasion up to that time in which this system of diverse but massed aerial assault would be realized: the attack on Pearl Harbor. But such an operation involving massed aircraft could not have been even contemplated had not the navy first developed a system of massing its aircraft carriers.

JAPANESE CARRIER DOCTRINE

The dramatic advances in naval aviation in the 1930s widened the gap between reality and the navy’s formal tactical principles—its Battle Instructions, which were concerned almost exclusively with surface engagements. The revision of the instructions was a complicated and time-consuming process. By 1939, however, with the emergence of the concept of the decisive air battle, the rapid growth in Japanese naval air strength, and the development, in effect, of a naval air force with its own tactical priorities, the navy had come to recognize that the creation of an overall naval air doctrine could be achieved only by a major reorganization of the formal principles of Japanese naval thought. To this end, the Naval Staff College drafted a “Supplement to the Battle Instructions: Air Operations” (Kaisen yōmurei zokuhen: kōkūsen-bu), later distributed by the Navy General Staff to all units and stations. This statement, which served as an intermediate step on the way to a formal revision of the Battle Instructions, stressed the importance of preemptive attacks; a shift in target priorities for air attacks from the enemy’s battle line to his carriers; decisive air combat as a necessary prelude to victory by surface units; and the identification of land-based air groups as one of the principal elements of naval power. Measures to transform these principles into a formal revision of the Battle Instructions were incomplete at the opening of the Pacific War.49

The idea of a preemptive tactical strike directed at the enemy’s carriers as priority targets supposed, of course, a concentration of massed aircraft. As discussed earlier, the preemptive-strike concept had provoked a question of considerable difficulty and controversy within the navy: whether to concentrate or disperse the navy’s carrier forces in combat. This dilemma stemmed from a number of questions: Would the apparent advantages of a preemptive strike from a concentration of carriers be offset by the disadvantage of risking all one’s own carriers to a similar strike by the enemy? Or conversely, how would individually dispersed carriers provide for defense in case they were caught by a numerically superior enemy?

At the time of the China War, fleet maneuvers and table-top war games had led the navy to favor the doctrine of dispersal. For that reason, in 1937 the training and maneuvers of the navy’s two carrier divisions—the First (comprising the small carriers Hōshō and Ryūjō) and the Second (comprising the Kaga and Akagi)—were conducted separately. Therefore, the employment of Japan’s carrier forces en masse did not at this point extend beyond the table-top war-game stage.50 But the first years of the China War had revealed an increase in the combat capabilities of fighter aircraft, as well as the importance of massing attack aircraft, both for bombing impact and for defense against fighters. These years also saw the modification of the navy’s dispersal doctrine for carrier operations. As we have seen, small formations of attack aircraft were unable to do much damage to their targets and were vulnerable to Chinese fighters if unescorted. These conditions had soon led the navy to recognize that bombers were effective only if they were massed and protected by substantial fighter cover. Extending these realities to air war at sea slowly but inevitably led to the conclusion that carrier forces should be concentrated.51

The impetus for a shift to a doctrine of carrier concentration came from another quarter as well. In 1937, at the urging of Capt. Ōnishi Takijirō, the air power enthusiast, the navy had established an “Air Power Research Committee” (Kūchū Heiryoku Iryoku Kenkyūkai, or Kūi-ken for short)—a small study group ostensibly formed to assist in the development of operational and armaments planning, but in reality set up by the navy’s mainstream to keep the heterodox views of Ōnishi and the like-minded within carefully monitored channels. While the Kūi-ken never led a charge on the navy’s battleship orthodoxy, it gathered data on the effects of various kinds of ordnance under differing operational conditions, data that would be useful in pondering the effectiveness of an attack by massed carrier aircraft, as indeed it was so used in planning the Hawai’i operation.52

Actual training and practice also illuminated the problem. The 1939–40 fleet exercises centered on the effectiveness of coordinated air attacks by massed formations of dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and protecting fighters. In doing so, they highlighted even more clearly the problems of coordinating such attacks from dispersed carriers. Radioed instructions to dispersed carriers, for example, would sacrifice surprise, and preliminary concentration of air groups from widely dispersed carriers would needlessly consume precious aviation fuel.53

The solution to this dilemma, it has been claimed, came suddenly in 1940 to Genda Minoru, then serving as assistant naval attaché in London. As he later told it, he was sitting in a London movie theater and watching a newsreel that showed a concentration of American carriers steaming together in a box formation. It immediately occurred to him that not only could carriers operate together in a single formation in order to mass air groups for offensive operations, but the risk of discovery and subsequent attack on such a formation would be more than offset by the ability of the concentrated carriers to launch a larger combat air patrol.54 It also meant that massed carriers should be able to throw up a greater concentration of antiaircraft fire than could be achieved by any single carrier, though this left open the doctrinal question of fleet air defense, specifically the question of whether or not carriers would maneuver together and screening escorts would remain close to the carriers (see below).

As it turned out, in the year before the outbreak of the Pacific War the navy opted for a compromise between concentration and dispersal. In its plans for action against an enemy fleet, specifically in a carrier-versus-carrier engagement, the two carriers of each carrier division were concentrated, but the divisions themselves were to be widely dispersed, forming an enormous vee with the open side toward the enemy in order to make his encirclement possible.55 In fact, there was no opportunity to practice this formation, and it was never used during the war. What was practiced and employed early in the war was the box formation, in which Japan’s six fleet carriers were dispersed in a rectangular formation, 7,000 meters (23,000 feet) separating one from the next. (Fig. 6-5.)56

Photo. 6-1. Comdr. Genda Minoru (1904–89)

Yet Genda Minoru’s doctrinal discovery, if such it was,57 induced the Combined Fleet to undertake a number of operational experiments in the concentration of carriers. Early in 1941 the Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū combined to form a temporary training unit to perfect such operations. While these trials had some success, the absence of an overall carrier commander and the lack of a standardized training program for the fleet’s carrier divisions pointed up the need for a permanent carrier command.58 Up to that point, the navy’s carriers, as they were placed in commission, had been assigned to carrier divisions—generally two or three carriers to a division—and these divisions allotted to different fleets. Not only did both fleets and carrier divisions change from time to time, but there was little effort to work them together. Generally, fleet commanders—most of them in the battleship tradition—and even carrier division commanders were content with this arrangement, one that left carriers to function as important, but strictly adjunct, components of the battle line.

Fig. 6-5. The Japanese “box formation” for carriers, 1941

Source: Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 63.

But the commander of the First Carrier Division, Rear Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō,† saw in the potential of the navy’s scattered carriers a revolutionary means to achieve formidable offensive power. While not himself an aviator, Ozawa was well instructed in naval aviation matters, including carrier operations, by his subordinates, particularly Lt. Comdr. Fuchida Mitsuo.† Fuchida, the air group commander on the Akagi, continually preached to him the importance of carrier concentration and urged that the First and Second carrier divisions should train and operate together. Thus, Ozawa himself came to see the need not only to reorganize the carrier divisions but to harness all the navy’s air power under a single command. To that end, Ozawa had twice urged Yamamoto, now commander of the Combined Fleet, to authorize the formation of an “air fleet” within the Combined Fleet, so that all its air units—both carrier- and land-based—would come under a unified command, in order to train and fight together. Yamamoto, while undoubtedly recognizing the profound strategic implications of such a tactical concentration, twice deflected Ozawa’s recommendation, realizing, one supposes, that time would be needed to overcome traditionalists within the Combined Fleet itself. In June 1940, however, Ozawa took the risk of forcing Yamamoto’s hand by writing directly to the navy minister, outlining his ideas for an air fleet. Conscious of Japan’s accelerating drift toward war, Ozawa warned that such a force had to be organized while the nation was still at peace. Standardized training at all levels and practice in coordinating the movements of large carriers would have to be mastered in peacetime if the new force was to be effective in war. Yamamoto was understandably nettled by Ozawa’s going over his head with the air fleet concept, one that provoked heated discussion at the highest navy levels. But in December 1940 he authorized its implementation, thus ending the remaining opposition within the navy.59

The new organizational system retained carrier divisions but abolished combined air groups in favor of air flotillas, which were to be the land-based equivalent of carrier divisions (and in fact they had the same designation, kōkū sentai, in Japanese).60 The air fleet system itself started with the organization of the Eleventh Air Fleet, which was activated in January 1941 and consisted of three air flotillas, comprising eight land-based air groups. In the coming conflict this force was to spearhead the navy’s thrust into Southeast Asia in the winter of 1941–42. But the real concentration of naval air power came in April 1941 with the creation of the First Air Fleet, headed by Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi† and composed of the First, Second, and Third carrier divisions, plus two seaplane carrier divisions and ten destroyers. (Later, that September, with the commissioning of the two new carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku, the Fifth Carrier Division was added, and the Third, comprising the small carriers Hōshō and Ryūjō, was detached from the First Air Fleet to provide cover for the main battleship force.)61

At the time it was formed, the First Air Fleet was the single most powerful agglomeration of naval air power in the world, specifically including the U.S. Pacific Fleet, comprising as it did all seven of Japan’s fleet carriers in commission and 464 aircraft: 137 fighters, 144 dive bombers, and 183 torpedo planes (figures that include reserve aircraft). One must understand, of course, that activation of the First Air Fleet was not a total break with the traditional mission or force structure of the Japanese navy. If one looks at both its organization and its command structure, it is clear that it was still a fleet created to participate in a decisive engagement whose main contestants would be opposing battleships—a scheme in which the Japanese navy persisted through 1943—and that it was not an independent tactical formation capable of undertaking a naval operation on its own. Indeed, it was to form only one component, though the single most important one, of the mobile task force (kidō butai) that Yamamoto sent across the Pacific for the Pearl Harbor strike. Nevertheless, I have to agree with Gordon Prange’s assessment that the First Air Fleet, in its massing of carriers, was revolutionary in strategic concept. I also agree that while it does not appear to have been created with the Hawai’ian operation specifically in mind, it is hard to see how that operation could have been conceived, let alone executed, without its existence.62

In important ways, the formation of the First Air Fleet, and the tactical arrangements derived from it, turned out to be paradoxical. The First Air Fleet was essentially a carrier force that had been formed to deliver a preemptive strike against enemy carriers. Yet for the first five months of the Pacific War the Japanese carrier fleet was unchallenged by a significant Allied carrier force, and thus it was largely directed against objectives on shore: Pearl Harbor, Port Darwin, Trincomalee, Colombo, and the installations at Midway.63

In considering the evolution of Japanese carrier doctrine in its final prewar form, it must be understood that as late as Midway, the Japanese navy still did not regard the carrier as the prime combat element of the fleet. Indeed, the main force at Midway was taken to be the battleship division built around Admiral Yamamoto’s monster flagship, the Yamato. It would not be until March 1944 that the Japanese navy would create the First Mobile Fleet, an approximation of the American carrier task force, to which other accompanying fleet units, including battleships, were subordinate. But like the First Air Fleet, it was designed as a quick strike force and had no mobile supply train for continuing offensive operations. In any event, by that time the Japanese navy lacked sufficient carrier strength and sufficient numbers of trained aircrew to match the true carrier task forces that were ranged against them.

Before leaving this discussion of the Japanese navy’s concern with concentrated carrier air power, it is important to touch briefly upon the larger offensive purposes to which such a concentration would be directed and upon the tactical problems it raised. In attacks against land-based air power, Japanese carrier doctrine held that a carrier’s mobility made the chance of a successful surprise attack considerable. But while carriers might be able to launch a burst of air power, their vulnerability made it particularly important to keep their intentions concealed. For that reason it was planned that upon entering a zone within reach of enemy patrols, a carrier formation should approach the target at a minimum of 25 knots, launch its strike at dawn and at a distance of 200–250 miles from the target, and then, in a majority of cases, retire at high speed. Should there be no danger from a counterstrike, a second strike could be ordered up.64

The problems posed by mounting a preemptive attack on an enemy carrier force were obviously greater, given the mobility of naval units, the vulnerability of aircraft carriers—one’s own and the enemy’s—and the need to knock out the enemy’s air power before he could launch his own attack. As early as 1939, various Combined Fleet maneuvers had demonstrated that success in preemptive attack was usually a matter of only a few minutes’ advantage. In this, much depended not only upon the time required for carriers to launch their attack squadrons but, even before that, upon finding the enemy first.65

AIR RECONNAISSANCE REVISITED

The problem of a preemptive strike brings us once again to the issue of reconnaissance, an activity about which there is sharp disagreement in postwar commentary on the navy’s conduct of the Pacific War. On the one hand, after the war Genda Minoru claimed that it was a defect so pronounced in the offensive capabilities of the Japanese naval air arm that it was “the vital cause of our defeat in the Pacific War.”66 Yet David Dickson, a student of the Battle of the Philippine Sea, June 1944, has argued that after Midway, “reconnaissance was the only area of carrier operations in which the Japanese remained superior to their American counterparts right up to the end of the war.”67

Genda surely exaggerated both the deficiencies of the navy’s air reconnaissance capabilities and their consequences. Yet there were severe limitations on those capabilities at the outset of the Pacific War, several of which were pointed out in chapter 2: an unwillingness to sacrifice offensive aircraft in order to embark reconnaissance aircraft on board carriers; an overdependence in blue-ocean operations on shipborne floatplanes that were not always reliable; and the weak training of reconnaissance aircrews.

The official history of Japanese naval aviation has identified other problems in Japanese naval air searches.68 Among these was the paucity of reconnaissance aircraft types that were fit for operations at sea—that is, capable of water landings—and that at the same time were sufficiently armed to ward off enemy fighter aircraft. That work cites as well the fact that aircrews in patrol aircraft were often worked to the limit of their endurance, increasing the probability that after two or three days of patrol duty, they would miss an enemy through fatigue and inattention.

In this view, the effectiveness of personnel assigned to reconnaissance also continued to be a problem. Great reliance was placed on the tactical judgment of such aircrews, but since the Japanese navy was obsessed with offensive operations, they were insufficiently trained to make sound decisions regarding aerial searches. This was particularly true of personnel who manned torpedo planes that doubled as reconnaissance aircraft. Their lack of concern with the reconnaissance mission was equaled by their lack of skill in navigation and communications.

Indeed, communications remained a vexing problem. As we have seen, the radio systems with which Japanese attack and reconnaissance aircraft were equipped before the Pacific War were generally radio telegraphs, rather than radio telephones. Among aircrews there emerged a considerable spread in radio telegraph transmission skills, depending upon the type of mission for which they had been specifically trained. The skills of aircrews regularly assigned to reconnaissance aircraft were generally good (such crews could transmit approximately seventy to seventy-five Japanese phonetic symbols per minute, on average); those aircrews in attack planes assigned to reconnaissance missions on an ad hoc basis were generally unskilled, except for those in the lead aircraft, who had been given advanced training.

Yet if Japanese naval air searches had deficiencies, one must not conclude that they were ineffective. To begin with, reconnaissance was certainly not neglected in the prewar Japanese naval air service. The navy had carefully worked out a reconnaissance doctrine that, on the face of it, was fairly sound. Just before the war the standard search method was a single-phase radial pattern out to 300–350 miles when the surface fleet was steaming under alert but not expecting an attack. The more demanding parallel-search pattern was a common variation. The ideal altitude for spotting the enemy on the horizon was judged to be 300–400 meters (1,000–1,300 feet) above the ocean’s surface, which limited vision to 30–35 miles. For maximum results, however, the standard altitude maintained was between 1,500 and 3,000 meters (5,000 and 10,000 feet).69

There is, as well, the mixed record of Japanese naval air reconnaissance in the Pacific War. Early in the war some outstanding successes were achieved by land-based reconnaissance units and flying boats, especially in relation to the Japanese invasions of Malaya and the Philippines. But the Japanese navy was to pay a terrible price for the neglect of rigorous air search procedures in the late spring of 1942. Certainly the mistaking of the U.S. oiler Neosho for a carrier during the battle of the Coral Sea was a costly error. But the allegedly spectacular reconnaissance lapse at Midway, often cited as one of the major elements in the Japanese disaster in that battle, has been strikingly reevaluated of late and the causes of the debacle located elsewhere.70 For his part, Eric Bergerud believes that a far more energetic reconnaissance effort by Japanese floatplanes and seaplane tenders stationed in the Solomons in the summer of 1942 might have alerted the navy to the U.S. movement toward those islands. As it was, the Japanese were taken completely by surprise when the American invasion fleet arrived off Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August.71

Yet one cannot think of a major Japanese naval air search failure for the rest of the war. In his grand account of the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that air search by both land- and carrier-based patrol craft was the one technique in which the Americans fell far short of perfection, but he specifically cited Admiral Ozawa’s air reconnaissance as one of the two redeeming features of the otherwise disastrous operation.72

FLEET AIR DEFENSE

The problem of a preemptive strike by carrier air power on an enemy carrier force also raised questions of fleet air defense. In considering such a strike, Japanese tacticians had to assume that the two strikes—one’s own and the enemy’s—would be launched about the same time. This being the case, considerable study on the eve of the Pacific War was devoted to two questions: first, how to preserve part of the strike force to finish off the enemy after reciprocal aerial attacks had caused reciprocal losses, and second, how to increase the defensive capabilities of one’s own carrier force to deal not only with the enemy’s first strike but also with his second.73 Because the Japanese navy was still wrestling with these questions as it plunged into war, it is important to comment briefly on the navy’s doctrine and capabilities in fleet air defense.

Although important consideration was ultimately given by the staff of the Combined Fleet to the problem of fleet air defense, too many years had been wasted in ignoring the problem to work out an effective air defense in the short time remaining before hostilities began.74 There were a number of reasons for this neglect. First among these was the practical difficulty involved in the detection of the approach of enemy fighters and in the organization of effective fighter direction in the years before the advent of radar. Among the navy’s air tacticians, these problems led to a consensus, based on the working out of the Fleet Problems of the 1930s, that it would be impossible to defeat completely an air strike launched against one’s own fleet. In addition, the importance of an effective fleet air defense was given little serious study in the 1920s and 1930s because the navy’s traditional obsession with offensive operations blinded it to all other considerations.

The inadequate provision for the air defense of its carrier task forces was an example of the Japanese navy’s failure to think through the issues of fleet air defense as a whole. At the outset of the Pacific War, the effective air defense of any carrier task force, Japanese or American, involved five critical elements: early identification of the attacking aircraft (their direction, altitude, speed, and strength); the proper vectoring of the force’s combat air patrol of fighter planes; effective antiaircraft defense to knock down whatever planes managed to slip past the patrol; evasive but coordinated movements by the carriers and their escorting warships to escape bombs and torpedoes yet keep their antiaircraft fire coordinated; and effective damage control to minimize bomb damage. Taken as a whole, it must be said that the Japanese navy’s tactics, technology, and organization were deficient in all five areas in varying degrees.

To begin with, any Japanese carrier group began the war with a critical technological disadvantage in confronting a similar American force. Whereas the United States Navy had begun installing service models of air search radar on ships in the summer of 1940, the Japanese navy only began testing shipborne radar before the Battle of Midway.75 Without this electronic means of early warning, a carrier task force had to depend upon distant surface units acting as pickets and on floatplanes orbiting at 20–40 miles. Yet there were usually too few of these to cover each direction from which an air strike could be made, and during the Pacific War, by luck or clever exploitation of cloud cover, American aircraft were sometimes able to approach a Japanese carrier formation within a few miles before being detected. This being the case, a Japanese carrier group would be obliged to depend on its next line of defense, the combat air patrol put up by the carriers themselves.

On the eve of the Pacific War, a Japanese fleet carrier usually embarked about eighteen Zero fighters. These were divided into two groups: nine fighters to provide escort to the outgoing carrier attack aircraft, and nine to stay above the Japanese carrier and thus contribute to the combat air patrol. But this number of patrolling fighters was far too small to provide for an adequate defense in all directions. Without radar, moreover, those directing the carrier group’s air defense in combat were obliged to work out a system of standing patrols with only a few planes in the air at a time: one three-plane shōtai aloft per carrier; another spotted for launch; and a third in a lesser state of readiness. Standard duration of a patrol was about two hours. If during that time an enemy flight was detected approaching the carrier group, the remaining six aircraft could be scrambled to join the CAP. Each individual fighter pilot was responsible for a sector of air space adjacent to his carrier, and theoretically other aircraft in the patrol could be vectored to any threatened sector.76

But there were serious drawbacks to these arrangements. First, the poor quality of the navy’s voice radio made it almost impossible to control CAP aircraft already aloft. Second, on the eve of the Pacific War, Japanese navy carriers carried no radar and thus were dependent on visual sightings of their combat air patrol and on whatever radio intercepts of any air activities they might happen to catch. Third, there were serious organizational problems in Japanese fleet air defense. Chief among these was the fact that responsibility for this activity was invariably divided among a number of officers aboard one of the carriers. The position of air defense officer was not permanent; rather, it was assigned on an ad hoc basis to any one of a number of carrier pilots who were otherwise unoccupied. Moreover, relay of urgent intelligence to those acting as air defense officers was often delayed because standing instructions required that such intelligence be passed through air group commanders.77 As a result of these deficiencies in fighter control, the navy was unable to use its limited CAP assets to maximum effect. More important, as the Pacific War opened, these weaknesses meant that the navy was poorly positioned to take the next step in fleet air defense: the installation of a central coordinating system like the American combat information center that would integrate information coming into a carrier from all sources—radio, radar, and visual sightings—and thus serve as a central point for the coordination of the combat air patrol.

One must also add that the Zero fighters themselves posed certain problems for a heavily engaged combat air patrol. While they were formidably armed with their powerful 20-millimeter cannon, the number of 20-millimeter shells they carried—sixty rounds per gun until later in the war—was too small for the kind of extended combat in which they sometimes found themselves. For that reason, too often they were forced to break off in the midst of air combat to return to their carriers for ammunition.

Japanese antiaircraft defenses also left a great deal to be desired.78 At the outbreak of World War II, this was true of all the world’s navies, of course. But the Japanese navy possessed antiaircraft ordnance that made it particularly difficult to adapt to the quickly emerging threat of aerial attack. The standard Japanese heavy antiaircraft weapon, the 5-inch (12.7-centimeter) Type 89 AA gun, was introduced in 1941 and was serviceable enough. But the fire-control system associated with the weapon, the Type 94 kōsha sochi, was inadequate in a number of respects, including its overreliance on manual inputs and control and thus its inability to track fast-moving targets and to develop a solution quickly. Most important, the navy never developed any antiaircraft ordnance equipped with a proximity fuze (see next chapter), which proved to be devastating to Japanese air attacks in the latter stages of the Pacific War. Both in numbers and in effectiveness, therefore, the Japanese navy’s antiaircraft defenses were overwhelmed by Allied air attacks during the latter stages of the Pacific War.79

The navy was even more deficient in light antiaircraft ordnance. The standard light AA weapon, the .60-caliber 25-millimeter Type 96 gun, had been developed from a French Hotchkiss design. While it possessed satisfactory ballistic properties, it was badly hampered by slow training and elevation speeds in its double- and triple-barreled mountings. Worse, it was hampered by a loading arrangement that required constant changing of magazines, dropping its maximum rate of fire from a theoretical 220 rounds per minute to an actual rate of approximately half that. It was, in sum, an unfortunate design that lacked the high sustained rate of fire of a good light AA weapon, such as the Swiss 20-millimeter Oerlikon or the great range and hitting power of the heavier 40-millimeter Bofors gun, both of which were used by the Allies in great numbers. Unable to upgrade its AA weaponry and pitted against rugged American aircraft, the Japanese navy was forced to conduct its antiaircraft defenses with weapons that were increasingly shown to be ineffective.