5The Economic Impact of the First Jewish Revolt on the Galilee

Mordechai Aviam

During the winter of 66 CE, Josephus Flavius, then Joseph, son of Mathaias, was sent to the Galilee as a governor by the Jerusalem revolt government. His mission, like all the other seven governors who were sent to their regions, was to take the reins of power from the Roman governing authorities. This included political leadership, sitting in judgment, collecting taxes, building a military power, and fortifying settlements.1

According to Josephus’s account, in his days there were 204 cities, towns, and villages in the Galilee (and Golan, as part of his governing region). A study of this account succeeded in proving that the number is realistic (Ben David, 2011). This high number of settlements by itself is evidence of the strong economy of the Galilee during the 170 years since the annexation of the region to the Hasmonean kingdom (Aviam, 2004: 41–50; Leibner, 2009: 315–30).

To try and show the development and changes in economic terms of the Galilee before and after the war, I will use four excavated sites as test cases.

Archaeological Reflections on the Economic Situation of the Galilee before the War

Yodefat

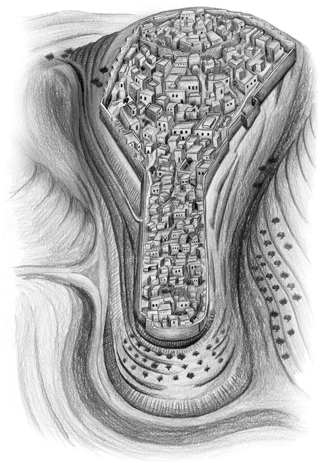

The excavations of this site took place between 1992 and 1997 and were led by the author in the name of the Israel Antiquities Authority with the assistance of David Adan-Bayewitz from Bar Ilan University (for the first three seasons), Douglas R. Edwards from the University of Puget Sound (for the first season), J. Andrew Overman from the University of Rochester (for the first two seasons), and William Scott Green from the University of Rochester. Two short seasons continued during 2019 and 2020, led by the author in the name of Kinneret Institute for Galilean Archaeology, Kinneret College, in which the entire “fresco building” was uncovered. The results of the excavations at Yodefat showed that in the early first century BCE, the site captured the summit of the hill and was surrounded by a wall, probably as a Hasmonean stronghold.2 During the second half of that century, the town started to grow slowly to the eastern and southern slopes, and in the first half of the first century CE, it also included the southern range (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Yodefat, reconstruction: on the eve of the First Jewish Revolt.

Source: Drawing by T. Rom for the Yodefat project. Used by permission.

The most important evidence for the prosperity of the citizens of Yodefat in the early Roman period is the Fresco House, which was discovered on the northeastern slope. According to the foundations of the walls, this was a very large mansion, which had at least ten rooms in the lower floor and basements.

All four walls of one of the rooms were covered with frescos of the Second Pompeian Style, and surprisingly, its floor was frescoed as well (Figure 5.2). The frescos can date the establishment of this unit and the units around it, on the terrace, to the end of the first century BCE or the beginning of the following one. In summer 2019, we renewed the excavation of this house and found that the western wall was preserved to a height of more than 2 meters, and above the frescos, the upper part of the wall still carried stucco decoration. The adjacent room to the north is of an unusual size, approximately 5 by 10 meters, and its walls are covered with white plaster, designed as ashlars, in the Masonry Style.

Figure 5.2 Interior of Fresco House, with skeletal remains and Roman arrows.

Source: Photo by the author.

The houses along the eastern steep slope, such as the Fresco House, were based on large and massive terrace-walls, which supported the entire quarter. This could have been built only in an organized system with a serious investment of money. A few other luxury objects were found in other parts of the town: two iron door keys (thus, people had a reason to lock their doors); a pair of small (5 cm in diameter) bronze scales, which were probably used to weigh valuable objects or powder; a multinozzle gray “knife-pared” oil lamp imported from Jerusalem; two ritual baths (miqvaot) were found in one building (probably two apartments in one unit). Together with the Fresco House, this all points to the wealth in the town, beyond the simple housing system of walls covered with mud plaster, bitten earth, and smoothed rock floors.

Gamla

A very similar situation was discovered at Gamla. The synagogue at Gamla was established at the beginning of the first century CE. Compared with other excavated Second Temple synagogues, it is a large synagogue, an elaborate building with decorated stone architecture (Syon and Yavor, 2010). Such a building clearly reflects the financial power and ability of Gamla’s population.

In areas R and S, located on the western side of Gamla, many fragments of stucco and fresco were found, identifying the quarter as a rich commercial one, with elaborate rooms (Farhi, 2010). In this quarter, two workshops were discovered, a well-built oil press (Figure 5.3) and a flour mill operating at least two “Pompeian mills.” Another decorated element found in this quarter is a lintel decorated with a rosette and a palm tree on each side of it. All reflect a life of prosperity (Syon and Yavor, 2010).

Figure 5.3 Gamla oil press.

Source: Photo by D. Syon. Used by permission.

As at Yodefat, all areas that were excavated yielded a well-built and well-organized housing system.

Magdala

The third settlement from the first century BCE and first century CE that was largely excavated during the last decade is Magdala, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee.3 Although Magdala was not a polis, it was larger and more organized than a Galilean town like Yodefat or Gamla. The city probably began as a late Hellenistic village of fishermen, and after the Hasmonean conquest it started to grow and developed as a regional capital as reflected by the first phase of the quay, which is dated to this period (Lena, 2018). A large domestic area was uncovered, and it clearly reflects two different social structures, similarly to Yodefat and Gamla (Zapata-Meza, 2018).

Area A yielded two large wealthy houses. Building E1 has a room (probably a triclinium) paved with a colored mosaic floor holding the design of a rosette surrounded by meanders. Two of its courtyards are paved with basal smoothed flagstones, and there are two miqvaot in this house. To the west, on the other side of the street is another house with paved courtyards and a miqveh. The fact that no earlier buildings were found beneath these houses proves that they were constructed at the end of the first century BCE or the beginning of the following one.

Areas B and C uncovered well-planned quarters with perpendicular streets on north-south and west-east orientations. In contrast with Area A, these are small, simple houses: small rooms, no mosaic floors, no paved courtyards, and no miqvaot.

An important place should be given to the synagogue. This is the northernmost building in the city. The excavators dated the building to the first decades of the first century CE, and reported that there is evidence for an earlier structure below it. It seems clear that the synagogue was established together with the neighborhood south of it, and developed through the first decades of the first century CE. Although it is not the largest synagogue from the Second Temple period, it is the most elaborate one. The walls are covered with frescos in the Second Pompeian Style, the columns are covered with both frescos and stucco, and a mosaic floor covers the footway between the upper and the lower benches. During salvage excavations at the end of 2021, a western neighborhood was uncovered, and as part of it, another synagogue was found, similar in size to the first one but not as elaborate (Winer, 2021).

Tel Rekhesh

The last example is the Jewish farmstead uncovered on the top of Tel Rekhesh in Lower Eastern Galilee (Aviam et al., 2019). On the summit of the biblical tell, there are the remains of a compound of walls and rooms on an area of approximately one acre. Excavations were conducted mainly in the northwestern corner, where few rooms were uncovered. In the debris of the second floor, many fragments of frescos as well as stucco were found, which point to an elaborate room on the second floor. We assume that this was the room of the owner of the farmstead, who was a wealthy man (Aviam et al., 2019).

According to the typical Galilean pottery, which includes storage jars, cooking pots and bowls, and oil lamps, the site was dated to the first and second centuries CE. This date is supported by the discovery of three coins from these centuries, the latest dating to 120 CE. The discovery of many chalk vessels shards supports the identification of the inhabitants as Jews. In the southwestern part of the site, an isolated room (9 by 9 m) was discovered, with benches of ashlar stones around the walls. Two stone bases probably supported a wooden/mud roof. We identified this room as a synagogue (Figure 5.4), and it is the only rural Galilean synagogue excavated to date (Aviam et al., 2019).

Figure 5.4 Aerial view of the synagogue at Tel Rekhesh.

Source: Photograph courtesy of the Tel Rekhesh Expedition. Used by permission.

The Preparations for the War

Josephus’s description of the preparations for the war, by building a wall mainly around each settlement, was proven to be accurate in archaeological excavations and surveys (Aviam, 2008).

Yodefat

It was already noticed in earlier surveys that there is a wall around Yodefat, but it was only during our excavations (1992–1999) that we dated the wall and proved that this wall was built before and for the war (Aviam, 2015). The total length of the wall is more than 1 kilometer, and it is built with two techniques: in front of the accessible side in the north and in one part in the west, it is a casemate wall of about 4 meters wide; in other parts, it is a solid wall, 1.0–1.2 meters wide. It was built mainly along a topographical line in a pattern of “saw teeth” and a few towers. We found that the wall was built over some houses and dismantled a pottery kiln in the southeast. It also disconnected an oil press from the nearby house. The wall has very shallow foundations, and all together proved that it was built under pressure. We assume that more cisterns were cut, and we discovered one underground shelter, which was cut into the rock and contained a tunnel and caves in two layers.4 It is very clear that such a building project requires many workers (including those with specialized skills), as well as a massive investment.

Gamla

The wall of Gamla was built only on the northeastern side, as all other sides were protected by nature with sheer cliffs and sharp slopes. The wall is about 200 meters in length. However, it is not a straight line, as it was created by blocking entrances between houses, filling up rooms, and building segments of wall. Like the wall built at Yodefat, this wall was built while cutting through existing rooms of houses (Syon and Yavor, 2010: 14–40).

Magdala

As Magdala is one of the settlements mentioned by Josephus as part of his fortifying project, the excavators suggest that the synagogue was purposely dismantled. It was taken apart because it was out of the line of the “emergency wall.” Columns, covered with fresco and stucco similar to those fragments found in the synagogue, were found blocking the north-south street near the synagogue. The shops’ entrances along the west-east street south of the synagogue were blocked. It seems possible that this evidence is connected to the fortifications of the city.5

In at least three or four sites identified as fortified by Josephus, evidence for fortifications were identified: Gischala, Beer Sheba of the Galilee, Mt. Nitai, and Mt. Tabor (Aviam, 2008: 39*–52*). Josephus mentioned that he “built a wall” on Mt. Tabor approximately 5 kilometers in length in forty days. The remains of a Hellenistic/Roman wall surrounding the top of the mountain was never properly excavated. It is less than 5 kilometers, but it is possible that Josephus reused a Hellenistic wall like he did at Yodefat and probably at Beer Sheba of the Galilee as well. In any case, reconstructing a long wall like this one requires a lot of manpower as well as financial resources.

As we can deduce from the archaeological evidence, it is clear that in the half year that Josephus spent in the Galilee from his arrival until the first battle at Yodefat, there was massive activity that required substantial financial resources. We can assume that this money came primarily from the taxes that Josephus collected (as reflected in Vita 63, 72). Instead of sending part of it to Jerusalem and part of it to the Roman authorities, it was now invested in building operations in the Galilee. It is also possible that each of the governors came to his region with money given to them from the “war government” in Jerusalem.

The Effects of the War

The war in the Galilee started in the summer of 67 CE, though there were a few clashes in Cestius Galus’s attack in 66 CE, in which the village of Khabulon (Kabul) was destroyed (B.J. 2.503–505).

During the campaign of Vespasian and Titus, there were several battles: Yodefat, Yapha, Magdala (Tarichaea), Gamla, Mt. Tabor, and Gischala. Vespasian marched through the Galilee with an army of approximately 60,000 soldiers, and it is clear that this army caused a lot of damage and raided the villagers of the region. Josephus describes the beginning of the campaign as follows: “Both divisions made constant sallies and overran the surrounding country, causing trouble to Josephus and his men.… The Romans, enraged at his enterprise, never ceased, night and day, to devastate the plains and to pillage the property of the country-folk, invariably killing all capable of bearing arms and reducing the inefficient to servitude. Galilee from end to end became a scene of fire and blood” (B.J. 3.59–63).6 On the way to the first battle at Yodefat, the Roman army attacked and destroyed the large village of Gabara; Vespasian also “burnt all villages and country towns in the neighborhood; some he found completely deserted, in the others he reduced the inhabitants to slavery” (B.J. 3.134). Although we do not have any archaeological evidence supporting these descriptions, they are probable given that the Roman military activity included the intimidation and terrorization of civilians in order to decrease their opponents’ fighting ability before the Romans began their battles against the fortified towns and cities.

Yodefat

The first siege took place at Yodefat and, according to Josephus, who commanded the battle, it lasted forty-seven days. The topographical position of the town, its recently built walls, and the fighting spirit of the defenders were the reasons for the third-longest siege of the war, after Jerusalem and Masada. Josephus’s narrative is dramatic, describing heavy bloodshed. At the end, after the Romans invaded the town, he described a heavy massacre (B.J. 3.336–339).

Over the years, many scholars have doubted Josephus’s narrative of the war, but archaeological excavations point to the truth of Josephus’s account. The town was found destroyed, with many fire marks; there are ballista stones all over the town; there are bow and catapult arrowheads everywhere. Surprisingly, we found human bones in every room we excavated and heaps of gathered bones in every cistern we checked (Aviam, 2002). Many of the bones carried violent marks, and all of these point to a heavy massacre of men, women, and children, as described by Josephus. Our estimation of the number of dead in the town is approximately 7,000 (it is clear that Josephus’s number of 40,000 dead is purposely exaggerated) (Aviam, 2002). As the battle of Yodefat was the first one in the war, we think that the Jews did not want to surrender, and as the Roman army suffered a lot of casualties, the punishment was not only to slaughter many of the citizens, but also not to allow survivors to bury their dead: the bodies were left in the streets and houses to be a feast for the birds of the sky and the beasts. The town was abandoned. Moreover, presumably as part of their punishment, Jews were not allowed to return and resettle in the town. According to Josephus’s account, in addition to the 40,000 people killed, 1,200 were taken as prisoners of war (B.J. 3.337)

Yapha

During the siege of Yodefat, the Roman army launched a short attack on Yapha, a large village south of Yodefat and, in the end, the town was taken; and, according to Josephus, there were 15,000 dead and 1,130 prisoners (B.J. 3.289–306).

Gamla

After a siege lasting approximately three weeks, Gamla was conquered. According to Josephus’s description, the Jews fled up the hill while the Roman soldiers were chasing them from the bottom. At the end, all of the survivors from the battle gathered on the rocky summit and threw themselves down the steep cliff. Josephus writes that there were 4,000 casualties in the battle, and that 5,000 took their own lives (B.J. 4.80). In contrast with Yodefat, the total number of casualties is not too exaggerated. If there was room for 3,000 people in the town during periods of peace, it is possible that there were 6,000 to 9,000 people in the town with the addition of refugees from the Jewish villages around the town.

The town was completely destroyed and has never been resettled. It is possible that, like Yodefat, the Roman authorities did not allow Jews to return, as a punishment. During the excavations, only one human jaw and a fragment of a skull were found (Syon, 2014: 17). It is possible that this lack of human bones in the town reflects Josephus’s narrative of the end, where people were killed only on the summit. It is also important to know that, although two cisterns were discovered, neither was excavated, and we cannot tell if there were gathered bones there like at Yodefat.

Magdala

On its way towards Gamla, the Roman army surrounded Magdala. According to Josephus’s story, there was an intense debate among the citizens of the town. The “foreigners” who had escaped to the town from Tiberias and other places supported participation in the war, while most of the original inhabitants were ready to give up. A short siege ended with a quick attack by the Roman cavalry, entering the town from the lakeside. The actual last battle took place on the water when the Zealots fled to the lake on boats, chased by Romans on boats and rafts. All of them were massacred: “One could see the whole lake red with blood and covered with corpses, for not a man escaped” (B.J. 3.529). According to Josephus, 6,700 people were killed in the first attack and on the water. Vespasian ordered the execution of 1,200 of the elderly and weak. Six thousand young men were sent to Rome, and 34,400 were sold to slavery, while others (no number) were sent to King Agrippa. All together, approximately 50,000 people were within the walls of the town, according to Josephus’s account.

The archaeological discoveries did not identify any evidence of war in the town, but the boat excavated on the shore of Magdala was dated to the first century CE (Wachsmann, 1990). Arrowheads were found in this boat; thus, one might suggest a connection to the war on the lake (Syon, 1990).

The excavators suggest that the northern part of the town was an important commercial quarter with a market and shops, but it is clear that there was a rapid decline of this northern part of town in the late first century CE. This decline started with the abandonment of the synagogue, which was the northernmost building in the town, probably in the preparations for the war, and likely continued as a result of the battle. The rest of the town continued to exist (Zapata-Meza, 2018).

Conclusion

Since its creation as a Jewish region during the Hasmonean dynasty, the Galilee developed into a prosperous, highly populated area. The evolution of Sepphoris from a central town into a Roman-type polis and the establishment of a new Roman-style capital at Tiberias created a small region with two poleis surrounded by towns, villages, and a few farmsteads. The discoveries of richly decorated houses at Gamla and Yodefat, two field towns, emphasize the wealth that existed in many of the villages and undoubtedly extended into the cities. The two capitals had large public structures. A few of these are evident from archaeology, including theaters in Tiberias (Atrash, 2012) and Sepphoris,7 and a stadium at Tiberias, as well as possible palatial structures in Tiberias (Jensen, 2006: 141–4) and Sepphoris (Weiss, 2015: 57).

Before the Roman invasion of the Galilee in 67 CE, as described clearly and in detail by Josephus Flavius, who, as a governor of the region, was an eyewitness, there was a large operation of fortifying cities, towns, and villages, as well as appropriate natural sites. A list of these sites appears in both Life and Jewish War, and was evident in archaeological surveys and excavations. These building projects, as well as the building of an army and other preparations for the war, required large sums of money, which probably came from local taxation.

A massive attack was launched on the Galilee for half a year. The two capitals surrendered to the Romans with no battle. There was siege war lasting forty-seven days at Yodefat, and at Gamla, there was an almost month-long siege. A few villages were burnt down (such as Gabara), while property, fields, and crops were plundered. If we calculate the total number of Galilean war casualties, according to Josephus, we shall come to a total of about 110,000 dead and sold into slavery. According to my analysis, the population of the Galilee and Golan before the war was approximately 184,000 (Aviam, 2005: 36). According to Uzi Leibner, the number of inhabitants in his survey area is between 9,000 (using the minimum estimation) and 35,500 (according to the maximum estimation), and the size of his surveyed area is approximately one-eighth of the size of Jewish Galilee and Golan (Leibner, 2009: 335). So, if we take the average number from Leibner and multiply it by eight, we will arrive at the number of 176,000 inhabitants.

It is therefore very clear that the numbers given by Josephus are highly exaggerated in order to emphasize the entire event of the war and its results. In fact, apart from Yodefat and Gamla (the two main battles of the Galilean campaign, which were destroyed and abandoned permanently) and the shrinking of Magdala, we have no other archaeological evidence for other catastrophes in the region. It is clear that many people were killed and many were sold into slavery; I estimated the number of humans lost at Yodefat to be 7,000 people. We can assume that a similar number was lost at Gamla, as well as at Magdala and Yapha.8 According to my rough estimates, the victims of the war in the Galilee, including captives, numbered approximately 20,000 people. This amounts to approximately one-tenth of the population, which is a great loss. There was also a loss of property, but it seems as though the Galilee recovered very quickly from both losses.

The small farmstead of Tel Rekhesh is an example of continuity from the first to the second century CE, with no remains of destruction or abandonment in between. The walls that were built under Josephus, the governor of the Galilee, were partially demolished by the Romans as an act of victory (B.J. 4.117), and the rest of the walls were taken apart by the inhabitants themselves to be reused in new houses.9 There was no more need for fortifications after the war.

We can also compare the results of the Galilean war with the results of the Judean campaign in the First Revolt and the results of the second. After the First Revolt, Jerusalem was completely destroyed by the Roman army and abandoned by its Jewish inhabitants. A Roman army camp was built inside, but the Judean villages recovered, like the Galilean. The results of the Second Revolt were different: all Judean villages were destroyed and abandoned.

Notes

- For the division of the Jewish land into eight regions, the sending of governors, and Josephus’s activity in the Galilee, see B.J. 2.562–584. For the understanding of the implementation of the fortification project as reflected from in all regions, see Aviam, 2008.

- For a short summary of the excavation, see Aviam, 2015.

- The best reference book is Bauckham, 2018.

- For the preparations for the war, see Aviam, 2002.

- This part of the excavation is not yet published, even in a preliminary report, but it is visible on site.

- The translations of Jewish War are those of Henry St. John Thackeray (1927–1928).

- The date of the theater in Sepphoris is still under debate. According to Weiss, it was built at the end of the first century CE. See Weiss, 2015.

- Josephus also mentioned 6,000 dead at Gischala (B.J. 4.115), and “many” at Mt. Tabor (B.J. 4.54–61).

- This is probably the reason why the remains of the walls were not discovered at Sepphoris, Tiberias, Gischala, and other sites, but clearly identified at Yodefat and Gamla, which were destroyed and abandoned.

Bibliography

- Atrash, Walid. 2012. “The Roman Theater at Tiberias.” Qadmoniot 144: 79–88.

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2002. “Yodefat/Jotapata: The Archaeology of the First Battle.” Pages 121–33 in The First Jewish Revolt: Archaeology, History, and Ideology. Edited by Andrea M. Berlin and J. Andrew Overman. London: Routledge.

- _____. 2004. Jews, Pagans, and Christians in the Galilee: Twenty-Five Years of Archaeological Excavations and Surveys; Hellenistic to Byzantine Periods. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

- _____. 2005. “Yodefat: A Case Study in the Development of Jewish Settlement in the Galilee during the Second Temple Period” [Hebrew]. PhD diss., Bar Ilan University.

- _____. 2008. “The Fortified Settlements of Josephus Flavius and Their Significance against the Background of the Excavations of Yodefat and Gamla.” Pages 39*–52* in The Great Revolt in the Galilee. Edited by Ofra Guri-Rimon. Haifa: Hecht Museum/University of Haifa.

- _____. 2015. “Yodefat-Jotapata: A Jewish Galilean Town at the End of the Second Temple Period; The Results of an Archaeological Project.” Pages 109–26 in The Archaeological Record from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Vol. 2 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James R. Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Aviam, Mordechai, Hisao Kuwabara, Shuichi Hasegawa, and Yitzhak Paz. 2019. “A 1st–2nd Century CE Assembly Room (Synagogue?) in a Jewish Estate at Tel Rekhesh, Lower Galilee.” Tel Aviv 46, no. 1: 128–42.

- Bauckham, Richard, ed. 2018. Magdala of Galilee: A Jewish City in the Hellenistic and Roman Period. Waco: Baylor University Press.

- Ben David, Chaim. 2011. “Were There 204 Settlements in Galilee at the Time of Josephus Flavius?” Journal of Jewish Studies 62: 21–36.

- Farhi, Yoav. 2010. “Stucco Decorations from the Western Quarter.” Pages 175–87 in Gamla II: The Architecture; The Shmarya Gutmann Excavations 1978–1988. Edited by Danny Syon and Zvi Yavor. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 44. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Jensen, Morten Hørning. 2006. Herod Antipas in Galilee: The Literary and Archaeological Sources on the Reign of Herod Antipas and Its Socio-Economic Impact on Galilee. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2/215. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Leibner, Uzi. 2009. Settlement and History in Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Galilee: An Archaeological Survey of the Eastern Galilee. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Lena, Anna. 2018. “The Harbor.” Pages 69–88 in Magdala of Galilee: A Jewish City in the Hellenistic and Roman Period. Edited by Richard Bauckham. Waco: Baylor University Press.

- Syon, Danny. 1990. “The Arrowhead.” Pages 99–100 in The Excavations of an Ancient Boat in the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Edited by Shelley Wachsmann. ‘Atiqot 19. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- _____. 2014. Gamla III: Finds and Studies IAA; The Shmarya Gutmann Excavations 1978–1988. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 56. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Syon, Danny, and Zvi Yavor. 2010. Gamla II: The Architecture; The Shmarya Gutmann Excavations 1978-1988. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 44. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Thackeray, Henry St. John, ed. and trans. 1927–1928. Josephus: The Jewish War. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Wachsmann, Shelley, ed. 1990. The Excavations of an Ancient Boat in the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). ‘Atiqot 19. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Weiss, Zeev. 2015. “From Galilean Town to Roman City, 100 BCE–200 CE.” Pages 53–75 in The Archaeological Record from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Vol. 2 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James R. Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Winer, Stuart. 2021. “Second Ancient Synagogue Found in Migdal Alters Ideas of Jewish Life 2,000 Years Ago.” The Times of Israel. December 12. https://www.timesofisrael.com/second-ancient-synagogue-found-in-migdal-alters-ideas-of-jewish-life-2000-years-ago/.

- Zapata-Meza, Marcela. 2018. “Domestic and Mercantile Areas.” Pages 89–108 in Magdala of Galilee: A Jewish City in the Hellenistic and Roman Period. Edited by Richard Bauckham. Waco: Baylor University Press.