6The Economic Transformation of an Early Roman Galilean VillageA Keynesian Approach

C. Thomas McCollough

This paper has as its primary goal the description and analysis of the changes in the economic posture of a small Jewish village in Lower Galilee over the period of the early first century CE to the end of that same century with a focus on the period after 70 CE. Given the dearth of written sources for doing such work, the material culture recovered in the excavations of Khirbet Qana between the years 1998 and 2008 will, naturally, be the primary source for describing the economic life of the village. The paper will argue that these data reveal a pattern of economic behavior that shows signs of significant change in the latter decades of the first century (ca. post-70 CE), and that the changes reflect a complex response to colonization that entails both accommodation and resistance.1 The economic choices made in this period appear to defy the economic behavior model proposed in the classic work of Adam Smith and beg for the more dense model found in the work of John Maynard Keynes, and in particular the articulation of Keynes’s work in the studies of Robert Shiller and George Akerlof. As will be shown, Keynes’s inclusion of a notion of “animal spirits” provides insights into economic choices that seem to flout a rational negotiation of market forces, but rather reflect a more emotive or narrative-based approach to economic behavior.2

This study will also make the case for the importance of building an economic portrait of a region by beginning at the micro level and building out from that evidence to a more general theory of economic behavior. In the past, we have seen a persistent urban-centric bias in terms of the excavation of Roman and Byzantine sites in the Levant. Such concentration on urban remains excludes critical and inherently interesting information, and the sheer size and complexity of urban spaces inhibits a comprehensive understanding of the historical, social, and economic dynamics over time or in any given place. Evidence from village sites can contribute to a much more vivid picture of social forms of ranking, the nature and degree of integration into the larger political economy, and interconnections with commercial and cultural networks. Moreover, recent anthropological as well as historical studies of villages have argued against the long-held view that villages are essentially static entities, either in the sense of repositories of venerable traditions (the so-called “little traditions”) or in the sense of long-lived entities witnessing few changes in their material culture (Horden and Purcell, 2000). In the period that is relevant to this paper, for example, we find in the case of Upper Galilee in the transition from the Hellenistic to the Roman period, over a quarter of the villages ceased to exist, while other regions of the Galilee witnessed a spike in population and a correlate spike in the number of settlements and growth in preexisting settlement size (Frankel, Getzov, Aviam, and Degani, 2001; Edwards, 2007). Further, as the material remains from the villages have surfaced in greater quantity, narrow approaches to the economic landscape (e.g., the tendency to pigeonhole the economy of Roman Galilee as simply a political economy dominated by elites and imperial interests) have been challenged if not displaced by more complex and nuanced models. The data demand a model that can encompass evidence that shows signs of villages that “adapted and responded to their ecological circumstances influenced by their perception of the past, and their view of the future” (Edwards, 2009: 222). This can be manifest, for example, in indicators that villages were readily participating in patterns of trade and exchange in response to new infrastructure, greater monetization, and demographic shifts, while at the same time investing in structures and ways of life that ensure secure ties to a well-established if not ancient identity. The complexity of this economic landscape was succinctly captured in David Mattingly’s observations about the Roman imperial economy:

The pattern is one of a colorful mosaic of tied and free market activity.… We must conceptualize this in terms of a political economy that operated alongside a social economy that was in turn interleaved with a true market economy.

(Mattingly, 2006: 295)

The Site of Khirbet Qana

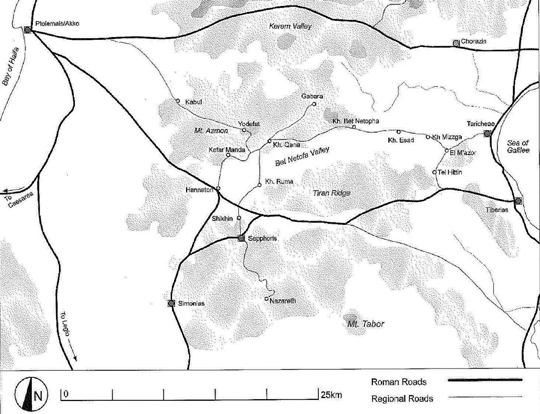

Khirbet Qana (“the ruins of Cana”) is located in the center of Lower Galilee, 7 kilometers north of the ancient city of Sepphoris and 15 kilometers west of Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee along a critical east-west corridor, the Beth Netofa Valley (see Figure 6.1). In terms of excavation history, no systematic survey or excavation of the site occurred until 1997, when Douglas R. Edwards initiated the University of Puget Sound excavations. That survey revealed plentiful evidence of human activity from the Neolithic through the Ottoman periods.

Figure 6.1 Map of Lower Galilee with Roman roads and paths.

Source: Drawing by James F. Strange. Used by permission.

In terms of the identification of the site, there are grounds for associating this village with the New Testament Cana of Galilee (John 2:1–11), as well as Josephus’s Cana (Vita 86).3 Khirbet Qana’s location on the edge of the Beth Netofa Valley just north of Nazareth and east of Sepphoris correlates well with the reference in Josephus.4 The excavations have made evident that it was a substantial Jewish village in the first century CE, and there is evidence of continuous Jewish presence until at least the sixth century CE (Edwards, 2002). Moreover, a thorough study of Christian pilgrims’ references to visits to Cana of Galilee concluded that until the seventeenth century, there was only one Cana that the pilgrims visited, and that Cana correlates with the location of Khirbet Qana (Herrojo, 1999). The excavations of Khirbet Qana have further solidified the link between the Christian pilgrims’ reports and this site by way of exposing an extensive veneration cave complex that included an altar-like structure with incised crosses, pilgrims’ graffiti, and fragments of stone vessels dating from the sixth through the twelfth centuries.5

The excavations that began in 1999 have recovered no evidence of substantial remains from the Hellenistic period. There is significant numismatic material from the Hasmonean period, but there are no structures to connect this village with local representatives of Hasmonean power. The village begins to emerge architecturally in the Early Roman period (37 BCE–70 CE) and was concentrated on the acropolis and the north, east, and west slopes of the small hillock (see Figure 6.2). The steeper south slope (facing Sepphoris and the Beth Netofa Valley) has no buildings until one reaches a plateau halfway down, where a separate small village was built, perhaps as late as the early Ottoman period. The south slope was also the location of the multichambered veneration complex.

Figure 6.2 Aerial view of Khirbet Qana.

Source: Photo courtesy of University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

The village’s location on the northern edge of the valley ensured access to one of the most fertile areas in the Galilee, second only to the Jezreel Valley (see Figure 6.3). Moreover, the valley served as the spatial framework within which the village operated and provided a natural approach to the Sea of Galilee and a visual connection to the urban center at Sepphoris.

Figure 6.3 Khirbet Qana and Beth Netofa Valley.

Source: Photo courtesy of University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

Prior to the construction of a Roman road in the valley connecting Akko/Ptolemais with Tiberias (6 km south of Khirbet Qana) in the late first century CE, travel between Khirbet Qana and other places of significant human habitation seems to have been entirely dependent on footpaths. However, the construction of this road opened important new horizons for trade and other modes of interaction with other places and people outside the village proper. While sure evidence of the village being interwoven into the growing web of connections facilitated by the road have not been exposed, the map showing Khirbet Qana connected to a regional road network is feasible given the clues found in the Tabula Imperii Romani: Iudaea, Palaestina (Tsafrir, Di Segni, and Green, 1994) and the studies of Avi-Yonah on the Roman roads in the Galilee (Avi-Yonah, 1977).

The location of twelve tombs encircling the area of habitation has enabled an approximation of the size of the village. The Early Roman village covered approximately 5 hectares. By way of comparison, it was about the same size as the nearby village of Yodefat/Jotapata, a bit larger than Nazareth, and smaller than Capernaum, which measured about 17 hectares. It was significantly smaller than the urban center of Sepphoris, which measured about 60 hectares. Presuming a relatively dense population coefficiency (similar to that used by Spigel for Gamla), the population estimate by the end of the first century CE would be 1,200 (Spigel, 2012).

Khirbet Qana before 70 CE6

The artifacts and architecture recovered from the early decades of the first century CE exposed a modest village lacking any public structures and consisting of small, unexceptional domestic structures that are primarily if not exclusively built on slopes of the northeastern quadrant of the site (see Figure 6.4). These are houses without private courtyards, each of which uses the roof of the house below as its courtyard.

Figure 6.4 Drawing of houses without separate courtyards.

Source: Drawing by Peter Richardson for University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

There is no architectural evidence for industry in this period. The village shows few signs of monetization. Interaction outside of subsistence agriculture appears to be largely limited to barter exchange within a network of Jewish villages, to include Kefar Hananya or perhaps, given the discovery of the pottery kilns at Yodefat, even more local. The coins that date to this period are predominantly Seleucid (which Danny Syon describes as “found regularly in Galilee”) and Jewish coins dating from 125 to 124 BCE (Syon, 2002). All indications are that the political economy manifest in the building of Sepphoris under Herod Antipas in the early decades of the first century CE had little impact on this village. In sum, the village appears to have been following a narrative that encouraged neither collaboration nor contestation, but a traditional, insular existence as the means for survival in an increasingly colonized landscape.

Khirbet Qana after 70 CE

The architecture and artifacts that emerge in the stratum that overlays this earliest phase of Roman period habitation show a striking shift in the enlargement of resources and expansion of trade relations, as well as deliberate efforts to retain a conservative/traditional Jewish identity. This is a layer that dates from roughly the mid-first century to the first two decades of the second century. In general, there are clear indications that the village was bolstered by human and material resources in the decades following the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem and the assault on and destruction of villages in the Galilee and Golan. The influx of assets may very well be related to the revolt and its aftermath (transfer of population and wealth from Judea and other villages), but in any case, these resources provided a basis for a transformation of the posture of the village from isolated to one of being connected and engaged in trade and industry. At the same time, as the village appeared to be tracking an economic course of action that was pragmatic and opportunistic, there also appeared to be countervailing dynamics that would ensure Jewish identity was preserved, especially at the intimate levels of foodways and sacred traditions. This type of hybridized posture of response to colonization reflected is not unique, as made evident by the work of Marianne Sawicki and, as noted previously, reflects economic behavior that incorporates a nonquantifiable “spirit” of resistance to the values and mores of the dominant power.

The first artifact that emerged which elucidates this complex dynamic are basalt grinders (both fragmentary and whole). In virtually every village that has been excavated in the Galilee, one will find grindstones and other implements (pounders, mills) made of basalt. When Jesus proclaimed that it is better that a millstone be placed around the neck of someone and be thrown into the deepest part of the sea rather than cause a child to sin (Mark 9:42), listeners would understand the sharp contrast of the heavy basalt millstone with leading a child astray. Despite the ubiquity of such stones and grinders, outcroppings of basalt in the Galilee are very rare; indeed only one clear example has been located, in eastern Galilee. Nearby, however, the Golan (ancient Gaulanitis) has a number of basalt outcroppings, making it the more likely point of origin for the basalt implements found in the Galilee. The raw basalt would need to be transported to workshops, and remnants of such workshops have been located around Capernaum (Xenophontos, Elliott, and Malpas, 1988). If the pattern of delivery from workshop to customer followed patterns revealed in texts recovered from Egypt as well as in the Mishnah, the artisan would take samples to villages and towns and then deliver the vessels by donkey train (Wolfe, 1952; Edwards, 2008). The basalt vessels found at Khirbet Qana have then arrived as the end point of an intricate arrangement of production and trade that shows no convincing evidence of being controlled by elites. As Edwards observed,

The complexity of the economy within and between Galilean villages and cities has often been underestimated and inappropriately tagged with this loosely defined “political economy” label. In villages we find activities that indicate active engagement by villagers in the local and regional economy that belie direct involvement of local elites in the cities.

(Edwards, 2007: 363)

The beginning point of Khirbet Qana’s involvement in this thriving village economy is difficult to establish with certainty as the vessels were recovered in nonstratified contexts or in later use. One indicator that these vessels are part of the late first century CE context is to see their use in correlation with the transformation of water-holding cisterns to holding grain, which can be dated with some certainty to the late first century CE. While storing grain in large quantities may reflect a change in soil or environment, it is more likely evidence of a move from subsistence agriculture to market economy, which in turn demands the use of large vessels for grinding (Longstaff and Hussey, 1997; Schoenwetter and Geyer, 2000).

A second object of material culture that manifests the shift in economic posture is the large public building exposed on the southwest quadrant of the site’s acropolis that has been identified as a synagogue (see Figure 6.5). The building was erected on a basilical plan. The large main hall (approx. 20 m by 15 m) is connected to a small room (approx. 3 m by 5 m) on the northeastern corner. The size of the main hall would have an estimated seating capacity of 225 to 250. The main hall is oriented north-south with an entry on the south wall. A Herodian-type bossed stone from the doorjamb was recovered on the floor of the main hall, suggesting a substantial and elaborate entryway. A sizeable fragment of a door lintel was also found. It is decorated with a rosette and garland. Several architectural elements (column base, flagstones) were found just outside the south entrance, suggesting a porch or courtyard on the south.

Figure 6.5 Aerial photo of possible synagogue.

Source: Photo by Skyview for University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

The outer walls of the putative synagogue are 1.5 meters wide and were plastered on both the exterior and interior. A hard-packed surface running along the outer western wall was exposed that sat directly upon quarried bedrock. It contained Early Roman period (37 BCE–70 CE) sherds. It appears to have served as a path or roadway. It is likely that the whole of the interior was painted, as fragments of the interior wall plaster were found decorated with red paint.

In the style consistent with other ancient synagogues, the interior of the building was divided into a central nave and two side aisles by way of eight interior columns. The foundation stones for the columns (footers) were recovered (5 m apart, north-south; and 2.5 m, east-west), as well as portions of column drums and stylobate fragments. A capital was uncovered that had been reused in the later transformation of the synagogue into domestic space. The capital’s decorative elements place it in the Ionic order with recessed volutes. There are also carvings of fruit hanging from the volutes.

There was no sign of a mosaic having covered the floors of the earliest phase of the building, but the floors of the aisles were paved with plaster, while the floor of the nave was covered with flattened bedrock. In the northwest corner of the interior, a bench was constructed of small field stones, which were covered with plaster. In the northeast corner, bedrock was shaped into a bench and again was overlaid with plaster.

As noted, a small room was connected to the exterior wall of the main hall at the northeast corner. Although the foundation of this room had been disturbed by Byzantine rebuilding, the excavations made clear that it was founded on quarried bedrock in the same manner as the large hall. In addition, the lowest level of debris within the room contained an overwhelming number of Late Hellenistic (152–37 BCE) and Early Roman sherds, suggesting that its original construction coincided with the building of the main hall. The room included a single low bench on three sides that was plastered. The plaster was subjected to radiocarbon (carbon-14) dating, and it yielded a date consistent with the floor of the main hall (100–300 CE). This, combined with the fact that the north wall of the room is not an extension of the north wall of the large building, suggests the room was added as part of the elaboration on the original building in the second century CE. The dating, size, position of the room in relation to the main building, and the inclusion of a bench aligns it with similar rooms uncovered in the course of the excavations of the Second Temple synagogues at Gamla (Syon and Yavor, 2010) and Wadi Hamam (Leibner, 2018). The Gamla room was identified as a “study room,” and this room may also have functioned as a small bet midrash (Syon and Yavor, 2010: 55).

An additional architectural feature of importance is the tegula—ceramic roofing tiles. A portion of the tiles that were recovered in the earliest levels of debris was subjected to petrologic analysis to determine compositional characteristics and possible provenance. In terms of the latter, a significant percentage (55 percent) of the tiles proved to be imported, primarily from Cyprus. The utilization of imported tiles has several interesting possible implications to include locating the village in a much-expanded trade network, as well as pointing to enhanced economic resources and a decision to expend such resources on a public building that had high cultural/religious value.

In an effort to date the founding of the building, probes to foundation level were made. These probes revealed that the structure was built in an area that had previously served as a place for quarrying stone. The stones used at founding level had been mortared, and there was plaster adhering to the exterior and interior surfaces of this wall. The very few readable sherds recovered were from a bowl and a cooking pot that had a start date of the late first century BCE and an end date of the beginning of the second century CE. The excavation of the founding level also recovered a coin of Antiochus IV and a Hellenistic lamp fragment.

The mortar used in the construction of the foundation wall contained residue that was successfully subjected to radiocarbon (carbon-14) analysis. The analysis yielded a date of 4 to 235 CE (95 percent accuracy). Having exposed plaster on the interior floor of the building, it too was examined with radiocarbon analysis to assist in dating the structure. A sectioning of the floor exposed two layers, and the earliest layer was dated from 100 to 330 CE (95 percent accuracy). The soil beneath the lower floor contained a small number of datable forms that were similar to those found in conjunction with the foundation wall: spanning the late first century BCE to the second century CE.

This ensemble of evidence posed a founding date that spanned the spectrum from the early decades of the first century CE to the late first or early second century CE. The judgment was made that in sum, the evidence pointed to a founding in the late first to early second century CE, with full elaboration (i.e., plaster floors, columns, bench along walls, addition of a possible bet midrash) by the mid-second century CE. This dating would coincide with the dating of other architectural features and artifacts cited and discussed herein to include the basalt vessel, an industrial installation for processing wool, and the expansion of the domestic quarter.

The third material culture indicator of economic status and choice is in the realm of domestic structures. Peter Richardson’s study of the domestic architecture of Khirbet Qana observed that by the end of the first century, the domestic area had expanded and, in addition to terrace housing without courtyards, included houses with side courtyards and at least one house with a central courtyard (Richardson, 2006). The houses that included courtyards located to the side of the main structure occupied the less steep northern slope. While these were simple houses with living space extending into the courtyard space, they were significantly larger than the terrace housing dated to the earlier decades of the first century CE. The courtyards included cisterns, and in one case, at least, we located a stepped pool that may have served as a miqveh.

The structure with the central courtyard was recovered on the northeast quadrant of the acropolis. Four large rubble core walls were uncovered that had been built to create a large room (12 m by 8 m). A pilaster built against the north wall appears to have been part of an arch supporting a second story. The pilaster is associated with a well-plastered floor still in situ. A small fragment of wall plaster with red paint along with pieces of marble were found in the fill nearby. The room was joined to a well-paved courtyard to the north and a small corridor to the west. A large, undecorated lintel was found resting on the courtyard pavers. Samples from the plaster floor that were subject to radiocarbon analysis dated them to the same period as the synagogue. While it is possible that this structure is a public building of some type, it appears more likely to be the remains of a large and somewhat opulent domestic structure similar to the elite house uncovered at Yodefat (Richardson, 2006).

The expansion and differentiation of domestic space provides further signs of a flourishing village, using its access to resources to enhance its living space, even at the cost of marking out social and economic differentiation. This is a pattern very similar to the one expounded by Sharon Lea Mattila in her studies of the domestic structures (and artifacts) uncovered in the Hellenistic- and Roman-period strata at Capernaum (Mattila, 2013). There is no indication of the owners/residents of this fine house, but it is worth noting that Cana is identified as one of the locations for the resettlement of the priestly course after the Great Revolt of 70 CE. Is it possible that this house, built in close proximity to the synagogue, is the home of the priestly family of Eliashib?7

The fourth and last of the economic indicators are the remnants of industrial activity. There are two such indicators, both located on the eastern slope. The first is a dovecote or columbarium. This is a bell-shaped dovecote that was hewn into the bedrock and plastered (see Figure 6.6). The form is typical of others found in Roman sites in Palestine and dated to the first centuries BCE/CE (Aviam, 2004).

Figure 6.6 Drawing of a columbarium.

Source: Drawing by A. Sönderlund for University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

The second industrial feature is a set of installations cut into the bedrock and built up with field stones that were then plastered (see Figure 6.7). These tub-like features are located near a large cistern. Two stepped structures that lead to underground chambers were built adjacent to these installations. One is just to the west and above the installations. It features five steps leading to a small (1 m by 1.7 m [east-west] by 2 m) underground plastered chamber. The second and larger stepped structure was uncovered 2.5 meters below and to the south of these installations. In this case, the five plastered steps lead to a circular underground chamber that measured 3 meters high and 4 meters in diameter. While the function of the installations is still not certain, recent research by Laura Mazow has pointed persuasively in the direction of use as fulleries (Mazow and Strathy, 2019). If this is the case, then the stepped structures may be miqvaot to serve purity demands for the workers, but it is more likely that they were used for storage and eventual distribution of the wool after processing. It is worth noting that among the artifacts reported to have been recovered at Khirbet Qana, there is a noticeable absence of indicators of spinning of wool (e.g., spindle whorls). On the other hand, at the nearby village of Yodefat/Jotapata, a number of items related to the spinning of wool were uncovered in the Early Roman layer of debris. Such finds fit with the growing body of evidence of craft and agricultural specialization as well as intentional complementarity among Galilean villages as they transitioned from subsistence and insularity to participating in trade and a market economy.8

Figure 6.7 Photo of industrial area.

Source: Photo by Douglas R. Edwards for University of Puget Sound Excavations. Used by permission.

These industrial features are, of course, important indicators of economic decision-making that manifest pivoting away from subsistence farming toward participation in trade and, on a limited scale, in the market economy. This pivot was certainly not unique to Khirbet Qana and in fact appears to have occurred earlier in other villages (Kefar Hananya, Capernaum) in response to the economic stimulation brought by the Hasmonean occupation of the Galilee and later Roman colonization. In the case of Khirbet Qana, such developments appear to have awaited those that occurred in the post-revolt period to include the construction of roads and the shift of resources, human and otherwise, from south to north.

Conclusion: An Economy of Adaptation and “Animal Spirits”

In some ways, the pattern of transformation we have tracked at Khirbet Qana is predictable and not worthy of special note given the increase in infrastructure and monetary resources that flowed into the Galilee. What is remarkable is the evidence of what Mattila called an “introverted trade pattern,” wherein the economic growth and dynamism is accompanied by what appears to be a deliberate pattern of inhibiting non-Jewish intrusion and by a determined effort of asserting the Jewish character of the village. We have noted the latter in architectural terms by way of the excavation of miqvaot and the synagogue. The latter can also be detected in the more intimate items of daily life such as ceramic forms, coins, and faunal data.

In terms of ceramic forms, through the middle of the second century CE, wares from the nearby Jewish villages of Kefar Hananya (and possibly if not probably Yodefat/Jotapata) and Shikhin make up the great majority of wares.9 There is a noticeable absence of imported wares such as ETSA (Eastern Terra Sigillata A), as well as local wares produced in pagan contexts such as GCW (Galilean Coarse Ware). Aviam’s summation of such a pattern of avoidance as a distinctive phenomenon of first-century CE Galilean Jewish villages, akin to avoidance of figurative art, seems apt for the results of the data from Khirbet Qana (Aviam, 2004). Given the evidence cited for economic growth and wealth, the absence of such wares does not appear to relate to cost, but rather points to a more deliberate decision. The issue of purity may factor into this choice, but I would agree with Andrea Berlin (2002, 2006) that nonpurity issues, including symbolic acts of resistance to Roman colonization, are at least as important, if not more so, in the choices made.10

The numismatic report simply reinforces the pattern detected above. As Danny Syon observed, the pattern at Khirbet Qana of Seleucid coins being gradually displaced by Hasmonean coins is consistent with other villages of the Galilee (Syon, 2002). What is noteworthy is the absence of a growth in Roman coins as the village moves into the early decades of Roman colonization. From the first three centuries of the Common Era, the excavations have recovered only one Herodian coin, four Early Roman coins, and, most conspicuously, no coins from neighboring Sepphoris. There was a significant number of Tyrian coins (and two from Akko/Ptolemais) that connotes active participation in trade, while at the same time spurning connections to Roman centers of economic activity.

And finally, the preliminary faunal report from the excavations revealed the absence of pig bones from the Early Roman assemblage. I take this to reinforce the arguments that while the village was taking advantage of opportunities to trade and to enhance the life of those living in the village, at the most intimate, immediate level of existence—coin exchange, pots and dishes for eating, cooking, storing—it was making deliberate choices to retain its cultural identity as a Jewish village.

The material culture uncovered in the excavation of this village perched on the edge of the Beth Netofa Valley in Lower Galilee discloses the dynamism and complexity of village life and, in particular, the economic and social dimensions of such in the Early Roman period. In the latter decades of the first century CE, this village pivoted from being a modest, insular entity to one crossing boundaries, taking advantage of new infrastructure, engaging in industrial endeavors, and reshaping itself architecturally. Indicators of social and economic differentiation also appear as a large public building in the heart of the village. Having survived virtually untouched by the upheavals of the mid-century, all the indicators point to a village that flourished by taking advantage of the opportunities that came its way. This is a set of choices that might easily be grasped in economic terms through the lens provided by Adam Smith’s view of a market economy that presumes people rationally pursue their own interests. We have noted, however, that there is another facet to the pattern, and that is an investment in cultural and religious identity. These choices reflect on the one hand that aspect of economic decision-making that John Maynard Keynes called “animal spirits,” a phrase based on the Latin spiritus animalis, meaning a basic mental energy or life force (Shiller, 2019: xvii). In terms of modern economic theory, the phrase has taken on the meaning of restless, inconsistent, ambiguous factors that at times trump rational selves in terms of economic choices. The purely rational self has to compete at times with the nonrational: the romantic, nostalgic, religious self. In the work of Shiller, he modifies the meaning a bit further to suggest that economic decisions are inextricably intertwined with the narratives that arise within a particular context and, when circulated orally or otherwise, give shape to economic decisions and changes:

We need to incorporate the contagion of narratives into economic theory. Otherwise, we remain blind to a very real, very palpable, very important mechanism for economic change.… If we do not understand the spread of popular narratives, we do not fully understand changes in the economy and in economic behavior.

(Shiller, 2019: xi)

While we do not have written narratives originating from this village as such, I believe we can detect the presence of “popular narratives” of resistance to identity dilution in the literature we do have from the latter decades of the first century CE and the decades immediately thereafter in the New Testament and Mishnah. For example, the New Testament’s descriptions of Jesus’s itinerant pathways show an avoidance of the new urban centers in Lower Galilee (Sepphoris and Tiberias), as well as the long-established urban areas of Tyre and Sidon. In the Mishnah, we witness a narrative that extends rabbinic influence “beyond purity and holy observances to such civil matters as marriages, the allotment of tithes and disputes over ownership and use of property” (Sawicki, 2000: 120). These narratives correlate with what we have revealed in the ruins of Khirbet Qana as the village constructed the architecture of resistance to a colonizing force that had pierced their land. The economic theories of Shiller (and Akerlof) thus provide an effective broadening to the analysis of economic decisions to capture the architectural and artifactual remains of this Jewish village in Lower Galilee as it found ways to live a life abundant and life of deep convictions while being swallowed up by a massive imperial enterprise.

Notes

- Marianne Sawicki’s (2000) analysis of the architecture of contact in her work Crossing Galilee: The Architecture of Contact in the Occupied Land of Jesus is especially insightful in mapping the strategies of response in Roman Galilee.

- See the work of Akerlof and Shiller (2009) for their use of Keynes’s notion of animal spirits in analyzing economic decisions.

- There are four other sites that have over time been identified as Cana of Galilee. Three of the possible sites are, as expected, located in Lower Galilee, while one is found in what is today southern Lebanon. The location of this latter contender is certainly odd, but its pedigree goes back to Eusebius of Caesarea’s Onomasticon. Eusebius noted there were two Canas, one near Sidon (“Greater Cana”) and another in the Galilee. Eusebius associates the water-to-wine miracle with Greater Cana, and this identification continues on in a few texts and maps into the medieval period. Given the biblical references (near Capernaum) as well as the references in Josephus (near Yodefat/Jotapata), Cana in Lebanon is no longer considered a viable candidate. The three sites in Galilee include Ain Qana, Kefar Kenna, and Karm er-Ras.

- See Steve Mason’s (2001) Life of Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Mason (2001: 69) remarks that Khirbet Qana has become the consensus location for Josephus’s Cana and, given Khirbet Qana’s “central location in Lower Galilee, with easy access routes, the nearby fortress [Iotapata/Yodefat], and a commanding view of both the main valley and the access to Iotapata, makes Cana an ideal location for Josephus.” The claim that the identification of Khirbet Qana with Cana of Galilee is aligned with the consensus of scholarship is also cited in Strange, 1992; Mackowski, 1979; and Conway, 2006.

- For a full description of the excavation of the cave complex and the correlation between the finds and the pilgrims’ reports, see McCollough, 2015.

- In terms of architectural remnants and artifacts, it is difficult to offer a definitive stratified portrait given the thin layer of soil that had accumulated over structures built into or on bedrock that consistently protrudes up toward the soil surface. Nonetheless, efforts were made to differentiate the strata relying on traditional ceramic and numismatic data combined with radiocarbon (carbon-14) results where possible.

- The full list of the twenty-four priestly courses appears in piyyutim or liturgical poetry, and the one that locates the priestly family of Eliashib at Cana (קנה) is that composed by Eleasar Qalir in the ninth century. The credibility of the poet as accurately depicting earlier traditions has been given support by the discovery of a third-century mosaic at Caesarea that has a list indicating the location of the twenty-four priestly courses after 70 CE that coincides with Eleazar’s lyrical poetry. For the ninth-century reference, see Klein, 1909; and for Caesarea, see Avi-Yonah, 1962.

- Edwards (2007) gives a full exposition of the emergence of these patterns.

- The discovery of pottery kilns at Yodefat/Jotapata producing forms similar to those produced at Kefar Hananya point to a broader level of village participation in the making and distributing of ceramics. See Aviam, 2014.

- See both Berlin, 2002, and her update to this argument in Berlin, 2006.

Bibliography

- Akerlof, George A., and Robert J. Shiller. 2009. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2004. “Columbaria in the Galilee.” Pages 31–5 in Jews, Pagans and Christians in the Galilee: 25 Years of Archaeological Excavations and Surveys; Hellenistic to Byzantine Periods. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

- _____. 2014. “Kefar Hananya Ware Made in Yodefat.” Pages 139–46 in Roman Pottery in the Near East: Local Production and Regional Trade; Proceedings of the Round Table Held in Berlin, 19–20 February 2010. Edited by Bettina Fischer-Genz, Yvonne Gerber, and Hanna Hamel. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1962. “A List of Priestly Courses from Caesarea.” Israel Exploration Journal 12: 137–9.

- _____. 1977. The Holy Land, from the Persian to the Arab Conquest. Rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Baker.

- Berlin, Andrea. 2002. “Romanization and Anti-Romanization in Pre-Revolt Galilee.” Pages 57–73 in The First Jewish Revolt: Archaeology, History and Ideology. Edited by Andrea Berlin and J. Andrew Overman. London: Routledge.

- _____. 2006. Gamla I: The Pottery of the Second Temple Period. Israel Antiquities Authority Report 29. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Conway, Colleen. 2006. “Cana.” Pages 531–2 in vol. 1 of The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible. Edited by Katharine Doob Sakenfeld. Nashville: Abingdon.

- Edwards, Douglas R. 2002. “Khirbet Qana: From Jewish Village to Christian Pilgrim Site.” Pages 101–32 in vol. 3 of The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Archaeological Research. Edited by John Humphrey. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 49. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- _____. 2007. “Identity and Social Location in Roman Galilean Villages.” Pages 357–74 in Religion, Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Galilee. Edited by Jürgen Zangenberg, Harold Attridge, and Dale Martin. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- _____. 2008. “Crossing Boundaries: Trade and Travel in Galilee and Its Environs.” Haywood Lectures, April.

- _____. 2009. “Walking the Roman Landscape in Lower Galilee: Sepphoris, Jotapata, and Khirbet Qana.” Pages 219–33 in A Wandering Galilean: Essays in Honour of Seán Freyne. Edited by Zuleika Rogers, Margaret Daly-Denton, and Anne Fitzpatrick McKinley. Journal for the Study of Judaism Supplement 132. Leiden: Brill.

- Frankel, Raphael, Nimrod Getzov, Mordechai Aviam, and Avi Degani. 2001. Settlement Dynamics and Regional Diversity in Ancient Upper Galilee. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 14. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Herrojo, Julián. 1999. Cana de Galilea y su localización: Un examen critico de las fuentes. Paris: Gabalda.

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicolas Purcell. 2000. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Klein, Samuel. 1909. Beiträge zur Geographie und Geschichte. Leipzig: Haupt.

- Leibner, Uzi. 2018. Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam: A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue in the Lower Galilee. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem/Israel Exploration Society.

- Longstaff, Thomas, and Tristram Hussey. 1997. “Palynology and Cultural Process: An Exercise in the New Archaeology.” Pages 151–62 in Archaeology and the Galilee: Texts and Contexts in the Graeco-Roman and Byzantine Periods. Edited by Douglas R. Edwards and C. Thomas McCollough. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Mackowski, R. 1979. “‘Scholars’ Qanah’: A Rexamination of the Evidence in Favor of Khirbet Qana.” Biblische Zeitschrift 23: 278–84.

- Mason, Steve. 2001. Life of Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Vol. 9 of Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Leiden: Brill.

- Mattila, Sharon Lea. 2013. “Revisiting Jesus’ Capernaum: A Village of Only Subsistence-Level Fishers and Farmers?” Pages 75–138 in The Galilean Economy in the Time of Jesus. Edited by David A. Fiensy and Ralph K. Hawkins. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Mattingly, David. 2006. “The Imperial Economy.” Pages 283–97 in A Companion to the Roman Empire. Edited by David Potter. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mazow, Laura B., and Diane Strathy. 2019. “Travelling on the Highway to the Fuller’s Field: Integrating Text and Archaeology to Reconstruct Wool Processing Technologies.” Paper presented at the American Schools of Oriental Research Southeastern Regional Meeting. Greenville, NC, March 9.

- McCollough, C. Thomas. 2015. “Khirbet Qana.” Pages 127–45 in The Archaeological Record from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Vol. 2 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple Period and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Richardson, Peter. 2006. “Khirbet Qana (and Other Villages) as a Context for Jesus.” Pages 120–44 in Jesus and Archaeology. Edited by James H. Charlesworth. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Sawicki, Marianne. 2000. Crossing Galilee: Architectures of Contact in the Occupied Land of Jesus. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International.

- Schoenwetter, James, and Patrick Geyer. 2000. “Implications of Archaeological Palynology at Bethsaida, Israel.” Journal of Field Archaeology 27: 63–73.

- Shiller, Robert J. 2019. Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Spigel, Chad. 2012. Ancient Synagogue Seating Capacities: Methodology, Analysis and Limits. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Strange, James F. 1992. “Cana of Galilee.” Page 827 in vol. 1 of The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Edited by David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday.

- Syon, Danny. “The Coins.” Appendix to “Khirbet Qana: From Jewish Village to Christian Pilgrim Site.” By Douglas Edwards. Pages 129–32 in vol. 3 of The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Archaeological Research. Edited by John Humphrey. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 49. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Syon, Danny, and Zvi Yavor. 2010. Gamla II: The Architecture. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Society.

- Tsafrir, Yoram, Leah Di Segni, and Judith Green. 1994. Tabula Imperii Romani: Iudaea, Palaestina: Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods; Maps and Gazetteer. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

- Wolfe, Ethyl. 1952. “Transportation in Augustan Egypt.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 83: 80–99.

- Xenophontos, Carolyn, Carolyn Elliott, and John Malpas. 1988. “Major and Trace-Element Geochemistry Used in Tracing the Provenance of Late Bronze Age and Roman Basalt Artefacts from Cyprus.” Levant 20: 169–83.