8RefugeesThe Missing Element in Discussions of the Galilean Economy in the Roman Period

James Riley Strange

Introduction

Refugee theory has developed within the social sciences for some decades, particularly in the fields of sociology and anthropology. More recently, geographers and archaeologists have joined the discussion, and the literature has grown and diversified. This increase may result in part from the many regions of the globe where political, social, and cultural issues of refugee migration have become acute, including countries in which these scholars live and in which they work. Archaeologists of the ancient Near East have also begun to deploy refugee theory to help them understand people movements caused by war, famine, natural disasters, and combinations of calamities as far back as the Bronze Age (Burke, 2011, 2018; Driessen, 2018). Refugee theory may therefore help archaeologists of later periods in this region as they refine their understandings of complex social systems, including economic exchange.

To that point, this paper is concerned with an archaeological problem: how to detect refugee movements in Palestine, out of Judea and into the Galilee, following the war with Rome near the end of the first century CE. Migrations of people within relatively short timespans create crises, and such crises happened frequently enough that they should be considered in discussions of the Galilean economy in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. For example, Hasmonean expansion northward near the turn of the first century BCE, the depopulating and repopulating of Sepphoris in 4 BCE, the building of Tiberias de novo in 18 CE, and the elevation and renaming of Bethsaida to the polis “Julias” (located in lower Gaulanitis, very close to the eastern border of the Galilee) circa 30 CE occurred before the two Judean wars with Rome, and archaeologists regularly interpret some material culture as evidence of population movements related to these events. Regarding migration generated by the trauma of war, there is good reason to anticipate finding evidence of refugees following 135 CE, when in response to the Bar Kokhba Revolt, Rome expelled Jews from Judea and forbade them from returning to Aelia, the former Jerusalem. Following 70 CE, however, the year in which the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the Second Temple but apparently did not expel people, it is less clear that refugees abandoned Judea; and if some did leave, detecting their arrival in the Galilee presents a challenge.

Our primary problem is that Judean refugees arriving in the Galilee during the late first and early second centuries CE ought to be virtually invisible to archaeologists, as we shall see. However, if we think it is plausible that some refugees moved into the region following 70 CE, then we ought to develop methods for detecting their arrival and the effects of their resettlement and integration, if that is indeed what they did, and if we can spot it. In this paper, I propose that an assemblage of finds from the site of Shikhin allows us to test a method for finding Judean refugees who arrived in the Galilee after the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in 70 CE. That assemblage consists of a large number of fragments and complete specimens of a style of mold-made lamp (a “Darom,” i.e., “Southern” lamp) (Sussman, 1982 [1972]), molds for forming these lamps carved into soft chalk, and a small kiln in which lamps of this type were fired (Strange and Aviam, 2017; Strange, n.d.).

Refugee Theory

The test begins by surveying some literature on refugee theory that frames the discussion of what to look for in the material record. We need an understanding of refugees and a model of population migration and resettlement that helps us generate hypotheses to explain how some Judeans could have integrated into the Galilean economy and to anticipate how that integration would have left a footprint in material culture.

Anthony Richmond’s discussion is useful because, in contrast to some earlier studies, he avoids constructing an artificial dichotomy between refugees who choose to leave their homes and those who are forced to do so. He argues for “a continuum between the rational choice behaviour of proactive migrants seeking to maximize net advantage and the reactive behaviour of those whose degrees of freedom are severely constrained” (Richmond, 1993: 10; emphasis original). In the literature, we often see references to two separate categories: “economic” and “political” refugees. By contrast, Richmond explains, “Between these two extremes, many of the decisions made by both ‘economic’ and ‘political’ migrants are a response to diffuse anxiety generated by a failure of the social system to provide for the fundamental needs of the individual, biological, economic and social” (Richmond, 1988: 12).

Naturally, Richmond is drawing on data from modern refugee movements prior to 1993, and his model assumes migrations across modern nation-state borders. Nevertheless, the differences between modern economic, social, and political realities and those in Roman Palestine do not hinder an adaption of Richmond’s model, which charts “the interaction between economic, political, social, environmental and bio-psychological determinants, on the one hand and, on the other, the importance of distinguishing predisposing factors, structural constraints, precipitating events, enabling circumstances and feedback effects of reactive migration” (Richmond, 1993: 12).

For our purposes, we can understand that the months-long siege of Jerusalem, the Zealots’ destruction of the city’s food stores, the 1.1 million people killed by famine and sword (Josephus, B.J. 6.420), the 97,000 enslaved (B.J. 6.420), the 11,000 captives who died while awaiting their fate during their incarceration in the temple’s court of women (B.J. 6.419), the thorough destruction of the city, and Vespasian’s confiscation and selling of land in Judea (B.J. 7.216–217) must have created a set of economic, political, social, environmental, and psychological circumstances that some chose to leave behind rather than to endure. This is the case even if we must greatly reduce the numbers that Josephus reports. It is plausible to anticipate that, if they were able to do so, those who experienced the aftermath of the war as a failure of the social system to provide for their fundamental biological, economic, and social needs would have left Judea to seek provision elsewhere.

According to Egon Kunz, once in a host society, “cultural compatibility” is the most influential factor leading to refugees’ satisfactory resettlement:

If … the refugees find a sufficient number of people in their new home who speak their language and share their values, traditions, lifestyle, religion, political views and food habits, and they are able to anticipate and evaluate their hosts’ actions and responses, the integration will be accelerated.

(Kunz, 1981: 47)

This cultural compatibility eases challenges for refugee integration while posing challenges for us, who look for evidence of new arrivals in material culture: both objects and ways of making objects that are new to the region. Richmond and Kunz tend to speak of decisions of individuals but let us think of decisions and movements made by households and extended families. Whereas we cannot account for the complex ways in which southerners and northerners felt about one another, or for the many different responses Galileans might have shown to an influx of Judeans (however many there were), or for how hosts and new arrivals negotiated power, we can use the archaeological record to look for Judean refugees in the Galilee after 70 CE.

Aaron Burke has proposed using Michael Cernea’s Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) model (Cernea, 2000) to help detect evidence of refugees’ flight from Israel and the city of Samaria, and their resettlement in and near Jerusalem following the eighth-century BCE Assyrian conquest. The IRR model is useful for this event because it identifies phenomena associated with refugees “that can be correlated with a line of archaeological evidence” (Burke, 2011: 44).

The eight phenomena of refugees are as follows.

-

Landlessness shows up in abandoned settlements and landscapes, especially if abandonment is matched by rapid expansion in other areas.

-

Joblessness in antiquity often becomes manifest in military conscription and projects that require large numbers of laborers. The rapid expansion of an industry might supply evidence of joblessness at Shikhin.

-

Homelessness is evident in attempts to mitigate it, usually through the expansion of settlements or rapid building of city neighborhoods, either within or outside the walls. At Shikhin, this might be seen in the construction of houses and the building or enlarging of an associated public building.

-

Marginalization presents a challenge for detection unless it results in concentrating, and hence isolating, the refugee population in certain neighborhoods.

-

Food scarcity may become manifest in effects that are difficult to detect, such as malnutrition or increased food production.

-

Increased morbidity and mortality can be inferred from additional burials or new cemeteries if they correspond with other phenomena.

-

Access to common property assets pertains to landscapes near villages and consists of land for pasture and crops, water supply, space to bury their dead, quarries, and similar resources. In the Galilee, an increase in cisterns, tombs, and quarried bedrock may indicate the arrival of refugees, but except for tombs, dating all of these features is notoriously difficult. At Shikhin specifically, we might include access to waste products from local industries as evidence of this phenomenon.

-

Community or social disarticulation refers to “a breakdown of kinship bonds” and “a loss of social capital,” and the economic loss and social isolation that result (Burke, 2011: 45). As an isolated phenomenon, it will be hard to detect archaeologically.

Indeed, to be identified, either these phenomena must sufficiently alter settlements and landscapes of the host culture, or an expedition’s methods must have what Burke calls “a high degree of resolution.” As we shall see, in many cases, refugees moving north following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE might have traveled in relatively small groups as extended families or individual households, and thus might not have left an obvious imprint.

The Challenges of Identifying Judean Refugees

At the outset, finding evidence of these phenomena in the material remains of the Galilee encounters several challenges. The initial challenge is that we are limited, first, to more or less permanent media—pottery, stone, metal, and bone; second, to those refugees who successfully integrated into the Galilee; and third, to those who did so in sufficient numbers to make refugee migration a plausible explanation for what we find when we dig.

The second challenge is that refugees appear in literature only by innuendo. Josephus, our chief chronicler of the First Revolt, gives no details about migration northward. Rather, he mentions Sicarii who fled to Egypt and Cyrene following the sacking of Jerusalem (B.J. 7.10–11). Similarly, Vespasian’s command to sell or lease “all Jewish territory” in Judea, which he now regarded as his private property, may have given some Judeans reason to leave (B.J. 7.216–217), but that is as confident as we can be. It also seems likely that the loss of Jerusalem and a large portion of its population would have created in Judea an economic hardship such that many would have abandoned it (B.J. 7.407–419, 437–442). Josephus neither confirms nor denies these suspicions.

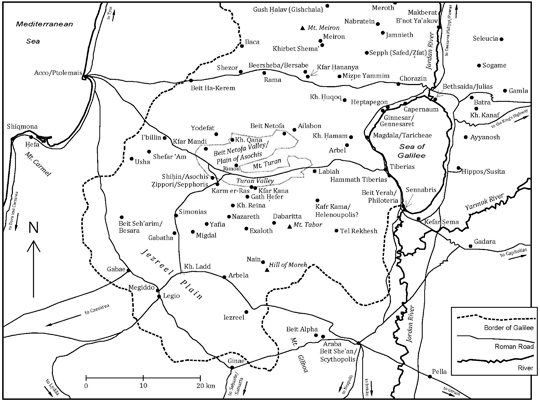

For his part, Dio Cassius gives us much less information about the Bar Kokhba Revolt than we want, and none about refugees (Hist. rom. 69.12–14). It is the fourth-century CE historian Eusebius who tells us that Jews were banned from Aelia, the city that Hadrian built on the ruins of Jerusalem, but he says nothing about refugee flight and resettlement (Hist. eccl. 4.6). The Mishnah gives some evidence of sages who after 70 CE moved to Yavneh/Jamnia (see, for example, m. Sheqal. 1:4; m. Rosh Hash. 4:1; perhaps m. Yad. 3:5), which lies on the Belus River near the Mediterranean coast around 20 kilometers south of Yafo/Joppa (modern Jaffa; Figure 8.1). A Sanhedrin apparently reconstituted there, from which the Babylonian Talmud reports that it moved into the Galilee perhaps as early as a decade later: to Usha, back to Yavneh, back to Usha, thence to Shefar‘am, Beth-She‘arim, Ẓippori (Sepphoris), and Tiberias (b. Rosh Hash. 31a–b; Figure 8.2). The reference is late; the dates, educated conjecture. If the Sanhedrin moved from Yavneh to Usha between 80 and 140 CE, it may be evidence of ongoing migration northward and the need to establish a judicial body in the Galilee. The events of either 70 or 135 CE could have supplied the proximate cause.

Figure 8.1 Map of Roman Palestine.

Source: Map by the author.

Figure 8.2 Map of the Galilee in the Roman Period.

Source: Map by the author.

From sixth-century liturgical poems (piyyutim, פיוטים), Samuel Klein reconstructed a list of Galilean towns in which priestly “courses” or divisions (mishmarot, משמרות) settled, and fragments of inscriptions found in Caesarea, Ashkelon, Kissufim, Tel Reḥov, and Yemen have supported his hypothesis (Klein, 1909: 66–7, 1923: 47; Avi-Yonah, 1962, 1964; Vardaman, 1964; Sukenik, 1926; Eshel, 1992; Dagen, 1973; Finegan, 1992; Miller, 2007: 375, n. 3). Listed in order, the towns are Meiron, Ẓippori (Sepphoris), Mafshitah, ‘Iṭhalo(n), Bet Leḥem (Bethlehem), Yodefat, ‘Eilabu(n), ‘Uziyah, Arbel, Kabul, Qanah (Cana), Ẓfat (Zefat), Bet Ma‘on, Shikhin, Yonit, Kefar Nimrah, Mamliaḥ, Naẓeret (Nazareth), ‘Arav, Migdal Nunia (Magdala/Taricheae), Kefar Yoḥannah, Bet Ḥobaiah, Ẓalmin, and Ḥammat ’Ariaḥ (Avi-Yonah, 1962: 138, Figure 8.1). Some of these towns have been identified; Shikhin appears as the village in which the course of Jeshebeab (ישבאב) settled (Figure 8.2). There is some debate about whether the courses are supposed to have settled following 70 or 135 CE. However, the presence on the list of Yodefat, which was destroyed in 68 CE and not resettled until people established a small village to the north of the ruined town in the late second or early third century CE, suggests that, if the roster is giving us good information, the migration may well have happened much earlier, in the Hasmonean period.1

Another inscription, this one in Greek and found on the lintel of an “elegantly styled” basalt mausoleum excavated near Tiberias in 1999, dates to the end of the second or beginning of the third century CE (Stepanski, 1999: 226). The façade of the mausoleum, which was the southernmost of a pair uncovered in a salvage excavation along Road 348, measured around 9 meters wide. The interior would have accommodated up to ten burial chambers (five, possibly six, were excavated). As with many other mausolea of the region and period, the door was carved to resemble a four-paneled wooden door with a keyhole. Nothing of the façade remained except the foundation and one nicely carved cornice stone, which indicates that the exterior was probably well decorated. The inscription may indicate the migration of a family of Judean refugees and their successful integration into the host society. If this is the case, we may speculate that cultural compatibility between Judeans and Galileans facilitated that integration. The inscription reads, ᾽Ιωσηπου ᾽Ελεα / ζαρου του Σειλου / ῾Ωρησου (“[Tomb] of Joseph Eleazar / [son] of Silas / of Ḥoreshah”) (Damati, 1999). Emmanuel Damati interprets Ḥoreshah as a town in Judea and speculates that Silas moved with his family from Ḥoreshah to Tiberias following the Bar Kokhba War. He notes the significance that, if he is correct, by the third generation after their resettlement, the family’s “economic achievements enabled it to establish a magnificent mausoleum” (Damati, 1999: 92*).

Inscriptional evidence brings archaeology into the discussion, and it raises the second challenge to detecting refugee movement from Judea into the Galilee. The refugees we seek have been least visible in the material culture. The first problem is that the archaeological evidence from Judea suggests that people returned to their villages rather than abandoning them (Zissu and Ganor, 2009; Magen, Tzionit, and Sirkis, 2004). Hence, we must confess that we do not expect to find in the Galilee evidence of large numbers of refugees following 70 CE.

The second problem is in knowing what to look for in the objects that survive and that we can recover. That is, the cultural compatibility that eases integration masks the arrival of the refugees we seek. Consider the shared material cultures of Judeans and Galileans in the first century BCE up until at least the late first century CE. Based on decades of surveys and digs, we now expect to find in both Judean and Galilean settlements of the period, and in southwestern Gaulanitis, a “household Judaism”: a nearly identical assemblage of ceramic pots and lamps, chalk vessels, ritual baths, public buildings, and Hasmonean coins, and we expect them to be made in the same way (Berlin, 2005, 2014; see the recent challenge to this notion in Wassén, 2019). Without loupe or X-ray fluorescence gun in the field, or various forms of atomic spectroscopy in the lab, we cannot distinguish a storage jar found in Jerusalem from one found in Sepphoris. If Judean refugees took some of their things with them into the Galilee, many of the items vanished into their new environment. Expressions of regional distinctions in perishable media—clothing, hairstyles, makeup, and food preparation, for example—did not survive.

Consider the items left in the Cave of Letters during the Bar Kokhba War, particularly the wool and linen fabrics. All surely were in common use in both Judea and the Galilee (Yadin, 1963; see also Shivti’el, 2014, 2017; Shamir, 2018). The objects made from organic materials survived because of the arid climate near the Dead Sea. In the Galilee, these objects would not have lasted 1,900 years or so in the moist, alkaline soils. One thing that might survive and stand out is iron door keys, several of which were found in the Cave of Letters (Yadin, 1963: 94–9, figs. 33–7; Yadin published ten), and which are known from other hiding complexes (Tsafrir and Zissu, 2002). In the find spot of the cave, they indicate that people left their homes with hopes of returning. I am unaware of a cache of door keys found in towns or hiding complexes in the Galilee. One such key has been found at Yodefat (Aviam, 2015: 115–6, fig. G) and another at Shikhin. Without more information, however, one cannot say whether the key from Shikhin was brought from Judea, fit a door elsewhere, or belonged to a house at Shikhin.

Despite these distinctive challenges, it is useful to speculate about what we might find as evidence of Judean refugee migration into the Galilee. For example, we might find evidence of campsites beside known roadways where families and groups sheltered on their way north, particularly if such sites housed transients for decades (De León, 2013). It seems more likely, however, that we would find permanent evidence, such as signs of the phenomena associated with Cernea’s Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction model, or tomb inscriptions like the one in Tiberias that mention Judean towns as the family’s place of origin. For an example of what inscriptions can indicate, consider the cache of bullae found near the City of David and bearing names of Israelite kings. That is, Judahites named their children for earlier Israelite kings: Pinchas, Menachem, and Ahiav (a variation of Ahab). The excavators interpret these names as evidence that Jerusalem accepted refugees from Israel following its eighth-century BCE destruction by Assyria (Mendel-Geberovich, Chalaf, and Uziel, 2020; Chalaf and Uziel, 2020). Along those lines, we might anticipate a proliferation of images of the menorah and other temple implements, as people expressed grief over their loss, hope that the temple would be rebuilt, cultural and religious identity, all of these attitudes, or others that underline the derelict temple’s and ruined city’s ongoing importance in Jewish life.

Can we say that images of temple implements proliferated after 70 CE? Based on objects found to date, we know that before 70, temple implements do appear in enduring media, but not commonly on lamps. A coin minted by Mattathias Antigonus (40–37 BCE) shows what are very probably the temple’s seven-branched menorah on the reverse and the showbread table on the obverse. A famous fragment of a graffito etched in plaster found by Nahman Avigad in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem depicts a seven-branched menorah and what many interpret as the altar and the showbread table to the right of the menorah. A small, limestone sundial found in excavations near the Temple Mount bore an incised seven-branched menorah (for images, discussion, and bibliography, see Hachlili, 2001: 41–5). In addition to these, Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron found what looks like a five-branched menorah etched into a stone object in a drainage channel near the City of David (Reich, 2014). Sometime in the Second Temple or Bar Kokhba periods, a person etched a seven-branched menorah into the wall of a cistern at a site in the Judean Shephelah, near which someone else etched a cross, probably in the fourth century CE (Israel Antiquities Authority, [2017]). At Horvat Beth-Loya near Lachish, excavators found three seven-branched menorahs engraved into the doorjamb and lintel of the entrance to an underground olive press dating to the Early Roman period (Gutfeld, 2009). The seven-branched menorah on the limestone block found in the pre-70 CE synagogue at Magdala was an arresting discovery (Israel Antiquities Authority, [2009]). Rachel Hachlili notes that menorahs rarely appear on ossuaries, most of which date before 70 CE, and gives examples of three, one from before 68 CE and one dated by Rahmani between 70 and 135 CE (Hachlili, 2001: 45).

After 70 CE—perhaps within a decade—we do find images of temple implements and objects associated with pilgrim festivals on lamps of the new, so-called Darom (“Southern”) type, the earliest examples of which are generally thought to have originated in the Daroma region of Judea, although very similar types are known to have been made in Scythopolis/Beth-She’an of the Decapolis and Shikhin of the Galilee (Strange, 2015; Strange and Aviam, 2017). Varda Sussman has published several examples of these lamps showing menorahs. Others depict ethrogs and lulavs invoking Sukkoth, baskets of fruits and the seven species invoking Shavuot, the matzah of Passover, altars, glass lamps, and one showing the ark of the law (Sussman, 1982; cf. Kaufman and Deutsch, 2012; Adler, 2004; Israel and Avida, 1988; Lapp, 2016). We must note that of the six lamps showing menorahs that Sussman published, only one depicts a lampstand with seven branches (admittedly, some of the pre-70 CE depictions of menorahs also do not show seven branches), and the altars we see might reflect Greco-Roman motifs rather than the Jerusalem Temple’s altar. One lamp depicts door keys, which may indicate a hope of return to Jerusalem or a lingering connection to the city, with or without such hope (Sussman, 1982: 70, no. 92).

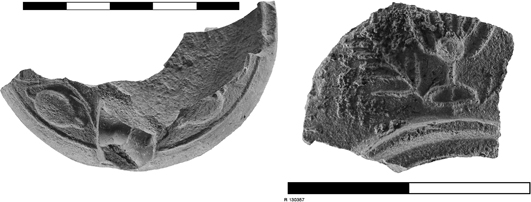

Darom-style (“Northern Darom”) lamps also appear in the Galilee at around the same time, but I am unaware of published examples that depict door keys. At Shikhin, we have found a single example of a lamp fragment with an image of a seven-branched menorah flanked by palm fronds, and others showing what are probably ethrogs (Figure 8.3; see the discussion of this fragment in Sussman, 2017b: 410–13; fig. 22). Based on the projected diameters of the lamps, the flatness of the shoulders in relation to the fill holes, the fabric, and the location and profile of the missing handle on the ethrog fragment, both appear to be from Darom lamps. A complete Darom lamp depicts myrtle leaves and berries, which may indicate an association with the festival of Sukkoth (Figure 8.4). A complete mold for making the top part of a Northern Darom lamp (Figure 8.5) has also been found at Shikhin. The decoration (carved intaglio into the mold, resulting in images in relief in the finished lamp) depicted tendrils with grape leaves and grape clusters with an amphora below the nozzle. The leaves and amphora on the mold resemble the decorations struck into the obverse and reverse of prutahs of year two of the Great Revolt, whereas the ethrogs on the lamp fragment resemble the design on the reverse of some prutahs of year four.2 These decorations continue to be found in Jewish art of the region for some centuries.

Figure 8.3 Right: a lamp fragment from Shikhin showing a seven-branched menorah flanked by palm branches. Left: a lamp fragment from Shikhin depicting ethrogs.

Source: Photos by Gabi Laron. Used with permission.

Figure 8.4 Northern Darom lamp from Shikhin depicting myrtle leaves and berries.

Source: Photo by Gabi Laron. Used with permission.

Figure 8.5 Mold from Shikhin for making the top part of a Northern Darom lamp; the decoration shows tendrils, grape leaves and clusters, and an amphora or vase below the space for the fill hole.

Source: Photo by Yeshu Dray. Used with permission.

But what can isolated objects tell us about the Galilean economy and the effect on it that Judean refugees might have had? After all, depictions of the menorah continue to appear on lamps of many different types for centuries (Kaufman and Deutsch, 2012; Sussman, 2017a; Lapp, 2016) and in many other media.

Proposal

The remainder of this paper presents material remains from the site of Shikhin that suggest that after 70 CE, some Judean refugees settled in the village and found ways to integrate into Lower Galilee’s economic system. If they achieved economic integration, they probably succeeded in other ways as well.

The 1988 and 2011 surveys of Shikhin and its environs produced a similar preliminary profile of settlement (J. F. Strange, Groh, and Longstaff, 1994 and 1995; Strange, 2012): human activity dates as early as the Iron II period (probably Iron IIC, 700–586 BCE) with indications of continued, sparse occupation in the Persian (586–333 BCE) and Early Hellenistic (333 to mid-second century BCE) periods. The number of Late Hellenistic sherds increases by about 38 percent, which suggests an increase in population sometime between the mid-second and mid-first centuries BCE. The number of Early Roman (mid-first century BCE to late first century CE) pottery forms increases by almost 60 percent, whereas the numbers of sherds dating to the Middle Roman (late first to mid-third centuries CE) and Late Roman (mid-third to mid-fourth centuries CE) periods steadily decline (about 20 percent in the Middle Roman period and about 16 percent in the Late Roman period). There were 40 percent fewer sherds dating to the Early Byzantine period (mid-fourth to mid-fifth centuries CE). In simpler terms, the survey teams found one sherd of the Late Byzantine period (mid-fifth to mid-seventh centuries) and none of the Early Islamic period (mid-seventh to mid-tenth centuries) (Strange, 2012). Field readings of pottery from excavations beginning in 2012 have largely borne out this initial picture with some refinements.3

The first hypothesis to explain the dramatic surge in the number of Early Roman sherds proposed two primary causes: a population increase coinciding with the resettlement of nearby Sepphoris when Herod Antipas rebuilt it in 4 BCE and the beginning of pottery production for regional distribution at around the same time. In Field I of the Shikhin Excavation Project, pottery manufacturing waste used to fill up a house’s basement preserved some important data that require the reconsideration of that hypothesis.

In the surveys and first two seasons of excavation, as a point of reference to test in the field, the directors adopted the archaeological periods derived from the findings of the Meiron Excavation Project and adapted by the University of South Florida Excavations at Sepphoris: the working hypothesis was that the Early Roman period lasted from circa 37 BCE to circa 70 CE, or from the beginning of Herod’s reign as a Roman client king to the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. For example, according to field readings, the lowest thirty buckets of pottery from the excavation of the fill in a house’s basement contained sherds dating from the Late Hellenistic to the Early Roman period, with not a single sherd read in the field as later. This pottery included hundreds of wasters from pottery production. With no coins from the context to help refine the dating, the initial assessment assigned the production of this waste to sometime in the decades between 37 BCE and 70 CE. However, these thirty buckets of pottery waste also contained fragments of Herodian/knife-pared lamps and of Northern Darom lamps. Based on evidence first gathered in Judea, Varda Sussman, Eric Lapp, and other lychnologists (specialists in ancient lamps and lighting techniques) have been dating the production of Darom lamps between 70 and 135 CE, the ends of the two local wars with Rome, with some speculation that Darom lamp manufacture continued after 135 CE (Sussman, 1982: 16; Lapp, 2016: 5, Table 1). Accordingly, the evidence recovered from the pottery dump at Shikhin required either dating the beginning of Northern Darom lamp manufacturing earlier, before 70 CE, or extending the Early Roman period beyond 70 CE (Strange and Aviam, 2017).

Some clues suggest the latter solution. The most important is that many of the Northern Darom nozzles recovered from these buckets show no signs of use, as is the case with a very large, black fragment of a Herodian lamp from the same dump (Figure 8.6) (Strange and Aviam, 2017; Strange, n.d.). The lack of burning on so many lamp nozzles suggests that the lamp fragments are also from production waste. That conclusion is strengthened by the discovery of molds for making Northern Darom lamps at Shikhin and wasters of Northern Darom lamps. If Sussman and others are right that Northern Darom lamp manufacture in the Galilee followed the origin of the style in Judea, then Shikhin provides evidence that its potters continued to produce Early Roman period common pottery forms beyond 70 CE, perhaps because of Shikhin’s close association with Sepphoris, which made peace with the Romans as war was breaking out in the Galilee (Meyers, 1999; Rapuano, 2013). Coins would help tremendously in shoring up this hypothesis; regrettably, none was found in that archaeological context.

Figure 8.6 Fragment of a large, unused knife-pared Herodian lamp found among waste from the manufacture of ceramics at Shikhin.

Source: Photo by Gabi Laron. Used with permission.

The manufacture of Northern Darom lamps at Shikhin also suggests that Judeans migrated into the Galilee in the decades following the year 70 CE, and that some became involved in local industries. That involvement undoubtedly would have been complex, as Galilean social systems accommodated, as they were able, the arrival of new peoples. For example, there is some evidence that Shikhin’s kilns manufactured and distributed lamps before 70 CE, in which case Judeans would have joined and expanded an existing industry.

As they developed their Northern Darom lamp production, Shikhin’s artisans began producing another type of mold-made lamp, Sussman’s “Northern undecorated” type (Sussman, 2012). The lamp resembles a knife-pared Herodian lamp that was formed in a mold rather than on a wheel (Figure 8.7). Even though the body and nozzle were formed as a unit in the mold, makers of Northern undecorated lamps also pared the nozzles as potters pared Herodian lamp nozzles after attaching them to the lamps’ wheel-made bodies.

Figure 8.7 A Northern undecorated lamp.

Source: Photo by Gabi Laron. Used with permission.

To my knowledge, currently no examples of Northern Darom lamps have been found outside of the Galilee. Accordingly, this undecorated type probably originated locally rather than in Judea. To make both Northern undecorated and Northern Darom lamps, Shikhin’s potters carved molds into soft chalk. Many of the mold blanks were made from waste cores that craftspeople discarded after turning chalk “mugs” on a lathe; the cores were sawn down the center lengthwise to create blanks into which molds for upper and lower parts of lamps were carved.4 Shikhin’s lamp industry, therefore, was able to exploit another local industry: the manufacture of chalk mugs, which ostensibly enabled their users to maintain ritual purity (Strange and Aviam, 2017).

Not counting twelve examples from Shikhin, Anastasia Shapiro recently examined a small sample of twenty-two lamps and lamp fragments from six sites in the Galilee and one in the Golan: Yodefat (2), I‘billin (6), Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam (4), Makberat B’not Ya‘akov (2), Tel Rekhesh (1), Daburiyah (5), and Gamla (2) (Shapiro, 2017). She determined that, in her sample, four sites had a total of fourteen lamps made of clay from the vicinity of Shikhin. Knife-pared Herodian lamps made of this clay were found at Yodefat (one), I‘billin (two), and Daburiyah (one). Northern undecorated lamps were found at I‘billin (one) and Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam (one or two). Northern Darom lamps were found at I‘billin (two or three) and Daburiyah (three or four). It is reasonable conjecture that if her sample were larger, she would find more Galilean sites at which examples of these three types were manufactured from clay originating near Shikhin. That is work for the future.

Shapiro has also determined that a Hasmonean “pinched” lamp found in a pit beneath Shikhin’s synagogue was made from local clays and that it was over-fired (Shapiro, 2017). This is an indication that lamps were made in the village between the late second century and mid-first century BCE. In combination with the evidence from I‘billin and Daburiyah, the identification of the Herodian lamp at Yodefat suggests that before 70 CE, Shikhin’s kilns had started producing knife-pared Herodian lamps for regional export. The manufacture of Herodian lamps could have continued after 70 CE, if the refusal of Sepphoris to join the revolt against Rome also meant that Shikhin—a village within Sepphoris’s jurisdiction and a mere twenty-minute walk from the city—was also spared. The discovery of Northern undecorated and Northern Darom lamps at Galilean sites produced from clay that originated near Shikhin suggests that the industry continued to at least 135 CE, and perhaps closer to the mid-second century CE, as it is also difficult to detect the direct effects of the Bar Kokhba War in the Galilee (Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam is an exception; Leibner, 2018; Leibner and Bijovsky, 2013).

Shikhin’s synagogue offers some further evidence to consider. Pottery and coins found in pits beneath its floor and pottery recovered from a section of one of its stylobates indicates that it was built no earlier than the late first century CE and maybe after 135 CE. Furthermore, it incorporated stones from an earlier public structure. The pitched roof of the latest synagogue was held aloft by Ionic columns built of drums varying in diameter between 63 and 67 centimeters.5 That diameter allows us to estimate the height of the standing columns at between 5.67 and 6.03 meters, or between around 19 and 20 Roman feet.6 It is possible that the building stretched over 18 meters in length.7 The threshold in the façade accommodated a double-leafed doorway 1.58 meters wide, or a little over 5 Roman feet (Strange, 2015). Because of the coincidence with the making and distribution of molded lamps at Shikhin, it is tempting to associate the dismantling of an earlier public structure and the construction of a large synagogue with the arrival of Judean refugees, and as an expression of identity and piety that in part responded to the calamity of 70 CE. Admittedly, this coincidence does not require causation as an explanation.

Returning for a moment to the common decorations on Northern Darom lamps, and to lamps and lamp fragments found at Shikhin, it should be noted that in Judea and the Galilee, aside from decorations on the shoulder, the shape of the lamp itself, with its distinctive bow- or axe-shaped nozzle and a pair of “wings” where the nozzle meets the body (Figures 8.4 and 8.5), is probably a marker of Jewish identity. (This is less assured with the similar style of lamps found at the more cosmopolitan Beth-She’an/Scythopolis, but it may be the case there as well.) If so, then the lamp itself offers evidence of refugee migration, for it appears to emerge in the aftermath of the catastrophe of the temple’s loss, and its first appearance in Judea (so far as we know), presumably followed shortly by appearances just south of the Galilee in western Decapolis (Beth-She’an) and Lower Galilee, suggests that people leaving Judea brought the lamp and the technology for making it with them.

More data are certainly required in order to reach firm conclusions. We can, however, say that without the evidence of the manufacture and distribution of Northern Darom lamps at Shikhin, the expansion of Shikhin’s pottery industry in the late first century CE need not point to the arrival of Judean refugees. The manufacture of Darom-style lamps, however, is the clearest suggestion that we are seeing evidence of refugee migration, even if the population of refugees was relatively small, for it is easier to explain that in the decade or so following 70 CE, during what were likely increased hardships in Judea, Judeans moved northward into a region with a strong cultural compatibility. That Galilean Jews traveled to war-ravaged Judea and returned with a new style of lamp and the technology for making it, or that northerners introduced the lamp type in the south, are more complicated explanations than the data require.

How to test the hypothesis? First, one possibility is to compare pottery from the thirty buckets at Shikhin that contained Early Roman period pottery, knife-pared Herodian lamps, and Northern Darom lamps with pottery recovered at sites destroyed in the late 60s by Romans, such as Yodefat, Magdala, and Gamla, particularly pottery from destruction layers. That comparison may enable us to detect morphological changes in pottery that we can assign to an Early Roman 2 or Middle Roman 1 period at Shikhin and other sites: the period between 70 and 135 CE or so. Second, we can reevaluate the Early (37 BCE–70 CE) and Middle Roman (70–250 CE) strata at other sites, looking for similar evidence of population growth and new industries at that horizon. If the hypothesis about what happened at Shikhin is correct, then even if it were limited, refugee migration and settlement may have happened in similar ways at other Galilean villages. Third, we can reexamine Early Roman pottery manufacture and distribution at Kefar Ḥananya, asking if the industry’s flourishing can be tied to the same period: 70 to 135 CE or later. Finally, at these sites we can look for sealed deposits from foundation trenches and beneath floors where pottery, lamp fragments, and coins might allow us to date construction to the late first or early second century CE. As at Shikhin, new construction, especially of public buildings, may corroborate other data from the site that suggest the settlement and integration of Judean refugees. The sum of evidence from many sites will permit the inference that we are seeing the phenomena associated with Cernea’s Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction model, such as joblessness (evident in the creation of Shikhin’s lamp industry or its expansion of one that existed), homelessness (visible in construction of new homes in whose courtyards the levigating of clay, throwing and molding of lamps, and firing took place), and access to common property assets (such as chalk vessel waste material for the molds).

Conclusion

Literary and material evidence does not support a claim that the destruction of Jerusalem and the war in Judea displaced large numbers of refugees that Richmond would rank on the reactive end of his continuum. The movement of some Judean refugees on the proactive end of the continuum—perhaps an extended family of lamp and mold craftspeople—into the Galilee provides a plausible explanation for the expansion of Shikhin’s lamp-making industry in the late first century CE. That industry produced a variation of a lamp form that apparently originated in Judea: the so-called Northern Darom lamp. A much larger population of refugee families no doubt came after 135 CE, although it should be noted that we have similar challenges in identifying material evidence of these people.

If the hypothesis presented here is correct, the site of Shikhin and its environs in Lower Galilee—the territory controlled by Sepphoris—shows how some refugees were able to integrate into various social systems, including the manufacture and distribution of goods regionally, and by extension into other systems, such as kinship, religious practice, education, and social ranking. Presumably, when various factors in Jerusalem or in the region of Judea created a social system that no longer provided for the biological, economic, and social needs of these people, they traveled to a region that offered a high degree of cultural compatibility: a host society sharing with Judea the cultural expressions of language, values, traditions, lifestyle, religion, political views, and food habits. There is no need to paint Judeans and Galileans as indistinguishable, or to brush away challenges to integration that Judeans might have faced, in order to anticipate that the cultural similarities between the new arrivals and the host society eased the transition of some. We should also anticipate that a lack of some advantages, such as skill in a trade, the possession of wealth, high social status, or a combination of these and other traits, hampered the integration of others.

Notes

- I thank Mordechai Aviam and Uzi Leibner for this insight.

- I am indebted to Yeshu Dray for this insight.

- For example, the excavation has recovered a few Late Bronze period sherds along with some evidence of a decrease in population in the Persian period and a possible period of abandonment in the third century CE. Furthermore, excavations began to turn up a very few Islamic sherds, together with some Islamic lamps and lamp fragments. The current explanation for the appearance of Islamic forms is that local farmers from Sepphoris or other nearby towns left them while cultivating Shikhin’s hilltop.

- Until sometime in 2018 or 2019, one could find many such discarded cores at two Galilean chalk vessel manufacturing sites, one about a kilometer south of Reina on Highway 754 and the other within the town of Reina itself. When Yeshu Dray took me to see these sites in June 2019, the one on Highway 754 had been bulldozed, and the one within Reina proper was being covered by a modern construction dump.

- These measurements were made in the field in 2019.

- The estimate is based on a factor of height = 1 diameter × 9.

- The building is not oriented north to south; rather, the southeastern exterior wall, containing a central threshold, faces around 30 degrees south of west.

Bibliography

- Adler, Noam. 2004. Oil Lamps of the Holy Land: The Adler Collection. Jerusalem: Ruth and Stephen Adler.

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2015. “Yodefat-Jotapata: A Jewish Galilean Town at the End of the Second Temple Period.” Pages 109–26 in The Archaeological Record from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Vol. 2 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1962. “A List of Priestly Courses from Caesarea.” Israel Exploration Journal 12, no. 2: 137–9.

- _____. 1964. “The Caesarea Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses.” Pages 46–57 in The Teacher’s Yoke: Essays in Memory of Henry Trantham. Edited by E. Jerry Vardaman and James L. Garrett Jr. Waco: Baylor University Press.

- Berlin, Andrea. 2005. “Jewish Life before the Revolt: The Archaeological Evidence”. Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 36, no. 4: 417–70.

- _____. 2014. “Household Judaism.” Pages 208–15 in Life, Culture, and Society. Vol. 1 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Burke, Aaron A. 2011. “An Anthropological Model for the Investigation of the Archaeology of Refugees in Iron Age Judah and Its Environs.” Pages 41–56 in Interpreting Exile: Interdisciplinary Studies of Displacement and Deportation in Biblical and Modern Contexts. Edited by Brad E. Kelle, Frank R. Ames, and Jacob L. Wright. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 10. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

- _____. 2018. “Refugees in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, Archaeology of.” Pages 1–6 in Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by Claire Smith. New York: Springer.

- Cernea, Michael. 2000. “Risks, Safeguards, and Reconstruction: A Model for Population Displacement and Resettlement.” Pages 11–55 in Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees. Edited by Michael M. Cernea and Chris McDowell. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Chataf, Ortal, and Joe Uziel. 2020. “Jerusalem, City of David: Preliminary Report.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 132. http://hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=25841&mag_id=128.

- Dagen, Reinar. 1973. “An Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses from Yemen” [Hebrew]. Tarbiz 2/3: 302–3.

- Damati, Emmanuel. 1999. “A Greek Inscription from a Mausoleum in Tiberias” [Hebrew]. ‘Atiqot 38: 91*–92*.

- De León, Jason. 2013. “Undocumented Migration, Use Wear, and the Materiality of Habitual Suffering in the Sonoran Desert.” Journal of Material Culture 18, no. 4: 231–45.

- Driessen, Jan, ed. 2018. An Archaeology of Forced Migration: Crisis-Induced Mobility and the Collapse of the 13th c. BCE Eastern Mediterranean. Aegis 15. Leuven: Presses Universitaires.

- Eshel, Hanan. 1992. “Fragments of an Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses from Nazareth?” [Hebrew]. Tarbiz 61: 159–61.

- Finegan, Jack 1992. The Life of Jesus and the Beginning of the Early Church. Rev. ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gutfeld, Oren. 2009. “Horbat Bet Loya.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 121. http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=1065&mag_id=115.

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2001. The Menorah, the Ancient Seven-Armed Candelabrum: Origin, Form and Significance. Leiden: Brill.

- Israel Antiquities Authority. [2009]. “One of the Oldest Synagogues in the World Was Exposed at Migdal (9/13).” Israel Antiquities Authority Archive. http://www.antiquities.org.il/article_eng.aspx?module_id=&sec_id=25&subj_id=240&id=1601.

- Israel Antiquities Authority. [2017]. “Engravings of a Seven-Branched Menorah and a Cross Were Discovered by Hikers in an Ancient Cistern in the Judean Shephelah.” Israel Antiquities Authority Archive. http://www.antiquities.org.il/Article_eng.aspx?sec_id=25&subj_id=240&id=4242.

- Israel, Yael, and Uri Avida. 1988. Oil-Lamps from Eretz Israel: The Louis and Carmen Warschaw Collection at the Israel Museum Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum.

- Kaufman, Josef Chaim, and Robert Deutsch. 2012. Haneroth Halalou: Ma collection d’anciennes lampes à huile d’Eretz Israël / My Collection of Ancient Oil Lamps from the Land of Israel. Jaffa: Archaeological Center Publications.

- Klein, Samuel. 1909. Beiträge zur Geographie und Geschichte Galiläas. Leipzig: Haupt.

- _____. 1923. Neue Beiträge zur Geographie und Geschichte Galiäas. Vienna: Menorah.

- Kunz, Egon F. 1981. “Exile and Resettlement: Refugee Theory.” The International Migration Review 15, nos. 1–2: 42–51.

- Lapp, Eric C. 2016. Sepphoris II: The Clay Lamps from Ancient Sepphoris; Light Use and Regional Interactions. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Leibner, Uzi. 2018. Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam: A Roman Period Synagogue in the Lower Galilee. Qedem Reports 13. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Leibner, Uzi, and Gabriella Bijovsky. 2013. “Two Hoards from Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam and the Scope of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.” Israel Numismatic Research 8: 109–34, pls. 29–30.

- Magen, Izchak, Y. Tzionit, and O. Sirkis. 2004. “Khirbet Badd ‘Isa—Qiryat Sefer.” Pages 179–241 in The Land of Benjamin. Edited by Izchak Magen, D. T. Ariel, G. Bijovsky, Y. Tzionit, and O. Sirkis. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Mendel-Geberovich, Anat, Ortal Chalaf, and Joe Uziel. 2020. “The People Behind the Stamps: A Newly-Found Group of Bullae and a Seal from the City of David, Jerusalem.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 384: 159–82.

- Meyers, Eric M. 1999. “Sepphoris on the Eve of the Great Revolt (67–68 C.E.): Archaeology and Josephus.” Pages 109–23 in Galilee through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures. Edited by Eric M. Meyers. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Miller, Stuart S. 2007. “Priests, Purities, and the Jews of Galilee.” Pages 375–402 in Religion, Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition. Edited by Jürgen Zangenberg, Harold W. Attridge, and Dale B. Martin. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 210. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Rapuano, Yehuda. 2013. “The Pottery of Judea between the First and Second Jewish Revolts.” Strata 31: 57–102.

- Reich, Ronny. 2014. “A Depiction of a Menorah Found near the Temple Mount and the Shape of Its Base.” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 130, no. 1: 96–101.

- Richmond, Anthony H. 1988. “Sociological Theories of International Migration: The Case of Refugees.” Current Sociology 36, no. 2: 7–26.

- _____. 1993. “Reactive Migration: Sociological Perspectives on Refugee Movements.” Journal of Refugee Studies 6, no. 1: 7–24.

- Shamir, Orit. 2018. “Textiles, Threads, and Cordage from the Cave of Letters: 2000–2001 Excavations.” Pages 189–220 in Dead Sea: New Discoveries in the Cave of Letters. Edited by Philip Reeder, Richard A. Freund, Harry M. Jol, and Carl E. Savage. New York: Lang.

- Shapiro, Anastasia. 2017. “A Petrographic Study of Roman Ceramic Oil Lamps.” Strata 35: 101–14.

- Shivti’el, Yinon. 2014. “The Use of Caves as Security Measures in the Early Roman Period in the Galilee: Cliff Settlements and Shelter Caves.” Caderno de Geografia 24, no. 41: 77–85.

- _____. 2017. Cliff Shelters and Hiding Complexes in the Galilee during the Early Roman Period. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 6. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Stepanski, Yosef. 1999. “Two Mausoleums on the Fringe of the Roman Period Cemetery of Tiberias” [Hebrew]. ‘Atiqot 38: 73*–90*. English summary: 226–7.

- Strange, James F., Dennis E. Groh, and Thomas R. W. Longstaff. 1994. “Excavations at Sepphoris: The Location and Identification of Shikhin Part I.” Israel Exploration Journal 44, nos. 3–4: 216–27.

- _____. 1995. “Excavations at Sepphoris: The Location and Identification of Shikhin Part II; With a Contribution by David Adan-Bayewitz, Frank Asaro, Isadore Perlman and Helen V. Michel.” Israel Exploration Journal 45, nos. 2–3: 171–87.

- Strange, James Riley. n.d. “Shikhin Lamp Kiln.” The Levantine Ceramics Project. https://www.levantineceramics.org/kilns/39-shikhin-lamp-kiln.

- Strange, James Riley. 2012. “Shihin, Survey.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 124. http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=2195.

- _____. 2015. “Kefar Shikhin.” Pages 88–108 in The Archaeological Evidence from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Vol. 2 of Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Strange, James Riley, and Mordechai Aviam. 2017. “Shiḥin Excavation Project: Oil Lamp Production at Ancient Shiḥin.” Strata 35: 63–99.

- Sukenik, Eliezer. 1926. “Three Ancient Jewish Inscriptions from Eretz-Israel” [Hebrew]. Zion 1: 16–7.

- Sussman, Varda. 1982 [orig. 1972, Hebrew]. Ornamented Jewish Oil-Lamps from the Destruction of the Second Temple through the Bar-Kokhba Revolt. Warminster: Israel Exploration Society.

- _____. 2012. Roman Period Oil Lamps in the Holy Land: Collection of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Biblical Archaeology Review International Series 2447. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- _____. 2017a. Late Roman to Late Byzantine/Early Islamic Period Lamps in the Holy Land: The Collection of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- _____. 2017b. “The Palm Brand and Lulav Motifs on Oil Lamps from Antiquity.” Liber Annuus 69 (2019): 395–440.

- Tsafrir, Yoram, and Boaz Zissu. 2002. “A Hiding Complex at ‘Ain-‘Arrub in the Hebron Hills.” Pages 7–36 in Late-Antique Petra, Nile Festival Building at Sepphoris, Deir Qal’a Monastery, Khirbet Qana Village and Pilgrim Site, ‘Ain-‘Arrub Hiding Complex, and Other Studies. Vol. 3 of The Roman and Byzantine Near East. Edited by J. H. Humphrey. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 49. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Vardaman, E. Jerry. 1964. “Introduction to the Caesarea Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses.” Pages 42–3 in The Teacher’s Yoke: Essays in Memory of Henry Trantham. Edited by E. Jerry Vardaman and James L. Garrett Jr. Waco: Baylor University Press.

- Wassén, Cecilia. 2019. “Stepped Pools and Stone Vessels: Rethinking Jewish Purity Practices in Palestine.” Biblical Archaeology Review 45, nos. 4–5: 52–8.

- Yadin, Yigael. 1963. The Finds from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Zissu, Boaz, and Amir Ganor. 2009. “Horvat ‘Ethri—A Jewish Village from the Second Temple Period and the Bar Kokhba Revolt in the Judean Foothills.” Journal of Jewish Studies 60, no. 1: 90–136.