|

“Is there a God, Lasher?”

“I do not know, Rowan. I have formed an opinion and it is yes, but it fills me

with rage.”

“Why?”

“Because I am in pain, and if there is a God, he made this pain.”

“But he makes love, too, if he exists.”

“Yes. Love. Love is the source of my pain.”

—Anne Rice, The Witching Hour

Geometry is co-eternal with the Mind of God before the creation of things: it is God Himself.

—Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) |

Theano is taking food from a large box: eggs, a crushed box of matzos, butter, and jelly. The large box is stamped “Perishable—A.D. 2080.”

Mr. Plex crowds against Theano, seizing the matzos with one of his claws, the jelly with another.

You yawn and walk over to observe Mr. Plex’s rapid motions. “Hungry, Mr. Plex?”

Theano breaks a miniature stalagmite from the cave wall and stirs the shivering eggs in a pan. The three of you sit beside the fire, the smoke rising like an offering from a stone altar.

You hear music coming from far away. A lone kithara player?

Theano smiles. “I want to show you something. I set it up while you slept.” She takes your hand and leads you to the cave entrance.

There is a large Christmas tree at the mouth of the cave. Some of the stalactites are decorated with holly. On the ground beneath the tree is a box of Christmas lights and ornaments.

You turn to Theano. “Magnificent! I didn’t know you celebrated such a feast.”

“It’s an old feast,” Theano says. “It goes back centuries before Christ. The winter solstice. An important time astronomically. That’s probably why God chose it as a time to be born.”

You shake your head. “Where did you get all this?”

Theano smiles at Mr. Plex, who beams with pride. “Mr. Plex helped me,” she says.

All around you is the smell of the Christmas tree, sweetly fragrant, and of the fire burning. You feel delicious in the warmth.

What’s that you hear? It seems that a kithara is playing somewhere, and a low voice is singing a slow mournful melody, an ancient Greek song. Gradually the song metamorphoses into a Celtic tune about a child lying in a manger.

You turn toward to Theano. “Hear something?”

“What?” Theano is lying on her side, looking at the cave entrance where crusts of frost are forming on the outermost stalactites. Very slowly, a figure begins to take shape—a man with a glowing thigh, facing the cave, his arms folded.

Theano doesn’t hear the spirit coming toward the cave. Shadows from the stalactites make the icicle phantom difficult to discern.

Mr. Plex is chewing and sucking on some scrambled eggs. “Sir, what’s the lesson for today?”

You shake your head, and the icicle phantom is gone. Perhaps it was merely a fragment from a fading dream.

“Sir?”

“Kabala,” you say. “It’s an esoteric Jewish mysticism that became popular in the 12th and following centuries. Much of the Old Testament, they claimed, is in code. That’s why scripture may seem muddled.”

Mr. Plex holds up his forelimb as matzo crumbs fall from his mouth. “Don’t beginners need a personal guide to avoid danger?”

You nod. “I’m your guide.” You pause. “The early roots of Kabala are traced back to Merkava mysticism.”

“Merkava?” Mr. Plex says.

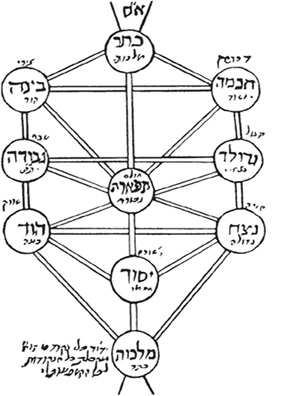

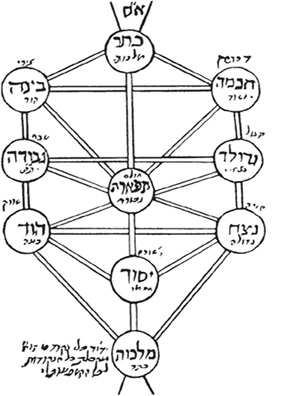

The Sephiroth Tree, or Tree of Life, from an old manuscript of the Zohar.

“Merkava is God’s throne-chariot as described in Ezekiel 1:26. The goal of early Jewish mystics was to ascend through the heavens and view God’s glory (kavod) seated on his throne-chariot.” You pause. “In Palestine, Kabala began to flourish in the 1st century A.D. The earliest known Jewish text on magic and mathematics, Sefer Yetzira (Book of Creation), appeared around the 4th century A.D. It explained creation as a process involving 10 divine numbers or sephiroth.”

Theano throws some new spruce wood on the fire, and the flames shoot upward.

You warm your hands by the fire. “The Jewish Kabala is the most important development of the Pythagorean tradition in the medieval world.” You pause. “Just like the Pythagoreans, the Jewish Kabalists considered numbers sacred and had a particular interest in the number 10.”

Mr. Plex jumps up. “Mon Dieu! The tetraktys. There’s that number 10 again.”

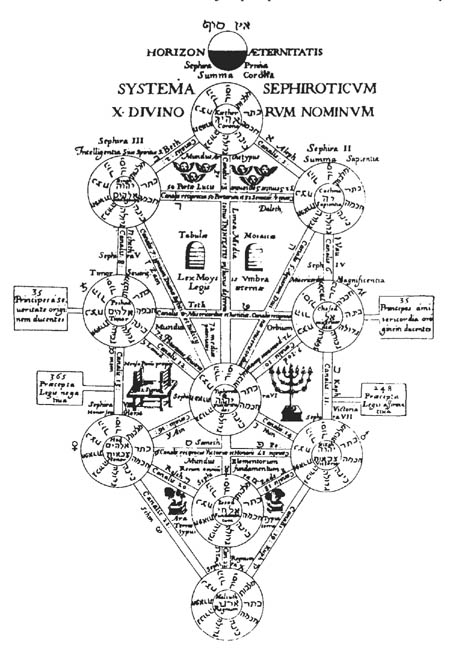

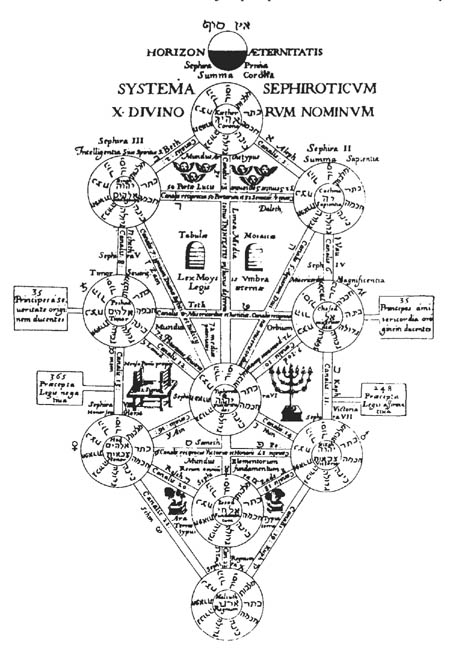

You nod. “Kabala is based on a complicated number mysticism whereby the primordial One divides itself into 10 sephiroth which are mysteriously connected with each other and work together. 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet are bridges between them.”

You grab a piece of charcoal and begin to sketch on the cave wall. “The highest sephiroth is keter (crown) out of which hokhmah (wisdom) and binah (intelligence) branch. The other sephiroth are: love, greatness, justice, beauty, triumph, splendor, fundament, and finally malkhut (or Kingdom or Reality). This last sepheria can be equated with the Shekhinah that live in the exile of this world.”

You begin to draw lines on your diagram. “Like I said, there are 22 ways that the sephiroth are connected. The Sephiroth are 10 hypostatized attributes or emanations allowing the infinite to meet the finite. (Hypostatize means to make into or treat as a substance, to make an abstract thing a material thing.) Through study of the 10 sephiroth and their interconnections, one can develop the entire divine cosmic structure.”

Another representation of the sephiroth, the central figure for the Kabala.

Mr. Plex throws another branch onto the fire. “Sounds heavy.”

Theano stretches her legs. “For my husband, 10 played a magical role. Was it magical for the Jews in other areas?”

You nod. “Ten appears often in Judaism.” You begin to outline your thoughts on the cave wall as you speak:

• |

There are 10 commandments. |

• |

The Zohar, the central text of the Kabala, says the world was created in 10 words, because in Genesis 1, the phrase “And God spoke” is repeated not less than 10 times. |

• |

There are 10 generations between Adam and Noah. |

• |

There are 10 plagues in Egypt. |

• |

On 10 Tishri, the Jewish Day of Atonement, the confession of sins is repeated 10 times. |

• |

On Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, 10 biblical verses are read in groups of 10. |

Mr. Plex has finished the box of matzos and is chewing on the cardboard box. “Sir, did the Kabalists use the sephiroth to interpret the Bible?”

You rip the matzo box from Mr. Plex’s forelimbs. “Yes. They gave each Hebrew letter a numerical value, a method known as gematria. For example, consider the passage in Genesis (49:10): ‘The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the gathering of the people be.’ ” You pause. “In Hebrew, ‘until Shiloh come’ is IBA ShILH (Yavo Shilo), and if we add together the numerical values of each letter, we get a total of 358. Since the Hebrew for messiah is Mshlch (Meshiach), and the letters also total 358, the Kabalists interpret this phrase from Genesis as a prophecy of the coming of the Messiah.”

You gaze into the burning fire. The only other illumination comes from the tree, which Theano has strung with countless tiny, twinkling lights.

The prophecy of the coming of the Messiah. Judgment day. End of the world. Why have we always been concerned with how the world dies? You sigh. Soon you will view the end of the Earth. You, too, are fascinated by endings.

You turn to Mr. Plex and Theano. “Kabalists also used numbers to understand the tetragrammaton or four-letter name of God. They wrote the name as IHVH which has become Jahweh or Jehova in English, but it was originally considered so sacred that it shouldn’t be pronounced. In fact, the only reason the Jews remembered it was that elders were allowed to pass it on to their disciples once every seven years.”

Theano’s eyes are clear, direct, penetrating. “This sort of thing would have made Pythagoras happier than a Centaur in heat.”

“Wait,” you say. “The best is yet to come. According to the Kabalists, Jahweh is itself a substitute for the true name of God which had 72 syllables and 216 letters! They call this holy name the Shem ha-meforash.”

“Mon Dieu!”

“Wait! To create the Shem ha-meforash, go to verses 19–21 of Exodus 14. Verse 19, 20, and 21 each have 72 Hebrew letters. Write Verse 19. Beneath it write Verse 20 in reverse order. Beneath Verse 20 write Verse 21. If you read from top down this creates 72 3-letter names, all of which can be connected together to make one name of God. Also, add to these 3-letter names AL or IH, and this creates 72 names for 72 different angels.”

“Wild,” Theano whispers.

“Wait! Amazingly, if the letters of IHVH are arranged in the form of a tetraktys, assigned their numerical equivalents, and added together line by line, the total comes to 72. Kabalists use the Shem ha-meforash and the 72 angel names to coax God and his angels to answer prayers.”

Theano’s eyes are unfocused. “All the numbers are swimming in my head,” she says.

You take a breath. “Me, too.”

Theano stands watching you as you climb a stalagmite and make some little adjustment to the tree. She is whistling a soft kithara song. So mournful, it makes you think of a deep ancient wood in winter. She leans against a stalagmite and looks at the immense tree all speckled with its tiny lights like stars, and breathes its deep woody perfume.

Theano walks over to a box of ornaments. “Aren’t they lovely!” She picks up a small white angel with golden hair. She replaces it and picks up a golden infinity symbol, with the faintest blush to its curves. “They’re beautiful. Where do they come from?” She lifts a silver fractal Koch curve.

Your recognize the box Mr. Plex has retrieved from the future. “I’ve had them for years. I could never have imagined that I would be using them to decorate a tree in a cave with you back in time.” You pause. “Pick one for the tree.”

“Koch curve star,” she says.

Theano hands the silver Koch curve to you, its triangles upon triangles glistening like diamonds. For an instant you feel like light trapped within a tube, totally internally reflected. You peer into the snow-flake curve, your image many times reflected as if you are standing on the periphery of some gigantic crystal, alone in a field of darkness.

You lift the Koch snowflake and place it on a branch. The fractal snowflake shivers. You are mesmerized by the lovely play of light on the deep green fractal branches. You need not move. There is enough motion from the lights. You feel like you can live forever, suspended in space.

The light is reflected according to mathematical laws. Angles, polarizations, intensities, refractions, diffractions, interferences, geometrical optics, spherical aberrations. Such beauty from pure math.

Theano snaps you from your reverie. “Here, I’ve gotten something for you,” she says. “Merry Christmas.” She places in your hands a small vessel wrapped in red Christmas paper. “It’s not a very big present, I’m afraid, but it’s the best I could find.”

You quickly unwrap the gift and smile. “Kylonian brandy, my favorite.”

Theano smiles. “Mr. Plex helped retrieve it for me from the past.”

You turn to Mr. Plex. “You are a good friend.”

Suddenly, there is a vague humming sound coming from deeper in the cave, like a church choir tuned two octaves lower.

“What’s that?” Theano says.

“Let’s check it out.”

You, Theano, and Mr. Plex walk a little further and see a small subchamber of the cave.

Mr. Plex stops. “Shall we go in?”

You nod. “Let’s find out all we can.”

Entering quietly, the three of you stand still and survey a bizarre, cold world of emaciated sleepers against the cavern walls.

“Oh, my God,” Theano whispers. “Th-there’s hundreds of them.”

Each alien appears as if it is in suspended animation. Their faces are partially covered by some kind of breathing mask with a snaking tube that goes into a hole in the wall. Their fragile limbs are hooked to flashing monitors amid a maze of cables and gauges.

Mr. Plex’s forelimbs are shaking. “Is it—?”

You nod. “The transfinites. What they really look like.”

A loud booming sound rolls across the cave, but you hardly notice the ominous beating. To you, the pounding of your own heart is the loudest noise in the cave.

A scream seems to be swelling inside Theano. As she holds it back you can only imagine the unreleased pressure as a painful burning in her chest.

The alien nearest you has skin that is bleached whiter than bone. It stands there against the wall, seemingly lifeless, its insectile head encased in an enormous turban of wires and tape. A thick amber tube runs into its mouth. A thin needle is taped to its right forelimb. The only sign of life is the blinking of the machines—machines that probably keep the creatures alive or quiet in this dormant state.

You back up. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” you say. The creatures’ gelatinous orbs sparkle like jewels. Their eyes are staring at you and Theano.

“Wait,” you say.

You feel like walking over to the support machinery, finding a power switch, and shutting it all off. But you can’t bring yourself to kill hundreds of sleeping creatures no matter how much trouble they’ve caused.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SCIENCE FICTION

Kabala was originally the post-biblical Hebrew name for the oral tradition handed down from Moses to the rabbis of the Mishnah and the Talmud. Later, toward the beginning of the 13th century, the term was applied to the mystical, numerical interpretation of the Old Testament. Usually a personal guide was used so initiates could avoid personal danger when unlocking the mysteries of the universe.

A major text of early Kabala was the Sefer ha-bahir (Book of Brightness, 12th century), which not only interpreted the sephiroth as essential in creating and sustaining the universe but also introduced into Judaism the concept of transmigration of souls (gilgul).

Following their expulsion from Spain in 1492, the Jews became increasingly interested in eschatology and messiahs, and the Kabala became more popular. By the mid-16th century, Safed, Galilee, was the center of the Kabala. In this sacred locale, the greatest of all Kabalists, Isaac ben Solomon Luria, spent the last years of his life. Lurianic Kabala had several main tenents:

• |

The withdrawal (tzimtzum) of the divine light, thereby creating primordial space. |

• |

The sinking of luminous particles into matter (quellipot). |

• |

Cosmic restoration (tiqqun) achieved by the Jew through an intense mystical life and struggle against evil. |

Lurianic Kabbalism was used to justify Shabbetaianism, a Jewish messianic movement of the 17th century. Lurianic Kabbalism also influenced the doctrines of modern Hasidism, a religious and social movement started in the 18th century and still flourishing today in certain Jewish communities.

As mentioned in Chapter 5 the number 7 plays an important role for Kabalists. In the 12th Psalm, it is said that the words of Yaheh are pure words, purified 7 times. The Kabalists use this fact to better understand biblical stories. The 7 lower sephiroth correspond to the Temple. The 7th of these lower sephiroth is the Shekhinah, which is called the Sabbath Queen, corresponding to the 7th primordial day.

The Kabalistic Loom

In the Kabalistic world view, everything is symbolic for something else, and the world is filled with subtle connections, as if reality were constructed from invisible threads binding events and ideas. Through study of the 10 sephiroth and their interweavings, one seeks to understand the cosmic structure. According to Kabalists, even the most trivial text, number, or object hides deep secrets. Kabalists believe that God created the universe by allowing some of his quintessence to flow “down,” transmuting into the material universe. The goal for many Kabalists is to understand this process, the universe, and the way back to God. The concept of God is complex. God has names with different powers ruling over hierarchies of angels, but God is also a completely abstract entity. Many Kabalists believe it is impossible to understand the nature of God, except to understand possibly what things God is not.1

A Loom of Universal Strings

The sephiroth as 10 hypostatized attributes linking the infinite and the finite remind me that physical reality may be the hypostatization of mathematical constructs called “strings.” Strings, the basic building blocks of nature, and not tiny particles but unimaginably small loops and snippets of what loosely resembles string—except that the string exists in a strange, 10-dimensional universe. The current version of the theory took shape in the late 1960s.

In the last few years, theoretical physicists have been using strings to explain all the forces of nature—from atomic to gravitational. As mentioned, string theory describes elementary particles as vibrational modes of infinitesimal strings that exist in 10 dimensions. How could such things exist in our four-dimensional space-time universe? String theorists claim that six of the ten dimensions are “compactified”—tightly curled up (in structures known as Calabi-Yau spaces) so that the extra dimensions are essentially invisible. Unfortunately, there are so many different ways to create universes by com-pactifying the six dimensions that string theory is difficult to relate to the real universe. In 1995, researchers suggested that if string theory takes into account the quantum effects of charged mini black holes, the thousands of four-dimensional solutions may collapse to only one. Tiny black holes, with no more mass than an elementary particle, and strings may be two descriptions of the same object. Thanks to the theory of mini black holes, physicists now hope to follow the evolution of the universe mathematically and select one particular Calabi-Yau compactification—a first step to a testable “theory of everything.”

Just like the early years of Einstein’s theory of relativity, string theory is simply a set of clever equations waiting for experimental verification. Unfortunately, it would take an atom smasher thousands of times as powerful as any on Earth to test the current version of string theory directly. I hope humans will refine the theory to the point where it can be tested in real-world experiments. Edward Witten, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, has worked on a related idea known as topological quantum field theory, which allows physicists to find connections between seemingly unrelated equations. With Witten directing his attention to string theory, it is hoped that he and his colleagues can crack the philosophical mystery that’s dogged science ever since the ancient Greeks: What is the ultimate nature of the universe? What is the loom upon which God weaves?

Whatever the loom is, it has created a structurally rich universe. Most astronomers today believe that the universe is between 8 billion and 25 billion years old, and has been expanding outward ever since. The universe seems to have a fractal nature with galaxies hanging together in clusters. These clusters form larger clusters (clusters of clusters). “Superclusters” are clusters of these clusters-of-clusters. In recent years, there have been other baffling theories and discoveries. Here are just a few:

• |

In our universe exists a Great Wall consisting of a huge concentration of galaxies stretching across 500 million light-years of space. |

• |

In our universe exists a Great Attractor, a mysterious mass pulling much of the local universe toward the constellations Hydra and Centaurus. |

• |

There are Great Voids in our universe. These are regions of space where few galaxies can be found. |

• |

Inflation theory continues to be an important theory describing the evolution of our universe. Inflation theory suggests that the universe expanded like a drunken balloon-blower’s balloon while the universe was in its first second of life. |

• |

The existence of dark matter also continues to be hypothesized. Dark matter consists of subatomic particles that may account for most of the universe’s mass. We don’t know of what dark matter is composed, but theories include: neutrinos (subatomic particles), WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles), MACHOs (massive compact halo objects), or black holes. |

• |

Cosmic strings and cosmic textures are hypothetical entities which distort the space-time fabric. |

What are the biggest questions? Perhaps, “Which laws of physics are fundamental and which are accidents of the evolution of this particular universe?” Or, “Does intelligent, technologically advanced life exist outside our Solar System?” and “What is the nature of consciousness?”

How many of these questions will we ever answer?