MODERN WRITERS sometimes state rather glibly that the only difference between the sexes is that women can bear children while men cannot. In the premodern world this simple fact had enormous consequences. Reproduction was the axis of female life. A fortunate bride not only brought into marriage the pots and sheep and kettles provided by her father, but also a set of “childbed linen” inherited from her mother, a mysterious collection of bedding and apparel which was as much ceremonial as practical. The finest childbed linen was embellished with embroidery or lace, like a best petticoat or pillowcase.1 The rituals of childbirth testified not only to the separateness and the subjection, but to the mysterious power of womankind.

LABOR AND DELIVERY were central events not only for the mother and baby but for the community of women. Depositions in an Essex County case of 1657 reported a dozen women present at a Gloucester birth. A hundred years later Matthew Patten of Bedford, New Hampshire, recorded the names of seven women gathered in the middle of the night when his wife’s travail grew “smart.” An eighth neighbor arrived in the morning.2 But Sarah Smith, the wife of the first minister of Portland, Maine, may have set the record for neighborly participation in birth. According to family tradition, all of the married women living in the tiny settlement on Falmouth Neck in June of 1731 were present when she gave birth to her second son.3

It would be helpful to know the rules which governed these assemblies. Were there particular tasks assigned according to consanguinity or status? Who, for example, supported the mother in delivery position? Who changed the linen? Did the midwife, the nurse, or the grandmother receive and wash the child? In this same-sex environment, were there procedures to preserve modesty? Could newlywed women or unmarried girls observe the actual process of birth before they experienced it themselves? On such questions the records are silent. Childbirth in early America was almost exclusively in the hands of women, which is another way of saying that its interior history has been lost. Yet in male diaries and in court depositions for the period there are shards of evidence which occasionally allow the historian to penetrate the silence and to make connections with the experience of women in other centuries and with the ragbag of English folk practice preserved in medical-advice books of the period.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries childbirth in America became a private ordeal undergone in the antiseptic sanctity of a hospital. The mother’s safety—and presumably her dignity—were ensured by the professional anonymity of the attendants. In the past twenty years this medical sanctuary has gradually been undermined. Today the home-birth movement welcomes not only lay midwives but sometimes children, friends, and neighbors as well, making birth the semi-public event which it was in the traditional world.4 But there is an important difference. In the past the badge of entry was sex. A shared gender identity shaped each detail of the drama of delivery.

For many women, the first stage of labor probably took on something of the character of a party. One of the mother’s responsibilities was to provide refreshments for her attendants. The very names groaning beer and groaning cakes suggest that at least some of this food was consumed during labor itself. Midwifery manuals encouraged the mother to eat light but nourishing foods—broth, poached eggs, or toasted bread in wine—during labor and immediately after birth. They told her to walk about rather than lie down at this stage.5

To relieve discomfort, the women used herbs gathered earlier from the field and garden. Most families had a supply of medicinal and culinary herbs; husbands as well as wives might be involved in their preparation. When Nicholas Gilman of Exeter, New Hampshire, went into the woods to gather betony in May of 1740, he was consciously or unconsciously following the instructions of an English midwifery manual of the seventeenth century, which recommended picking the plant “in its prime, which is in May.” Mary Gilman may have processed the herb which her husband gathered, crushing it, clarifying the juice, then making it into a syrup with double its weight of sugar. When she went into labor four months later, she was prepared.6

Remedies came from the barnyard as well as the forest. When Cotton Mather’s wife was suffering in her last illness, she dreamed that a “grave person” appeared to her and told her that the pain in her breast could be relieved by cutting “the warm Wool from a living Sheep” and applying it “warm unto the grieved Pain.” She confided the mystical remedy to her physician, who encouraged the family to try it.7 The remedy which so amazed Mistress Mather’s husband was actually an ancient device for relieving labor pain.8 It had probably existed in oral tradition long before it appeared either in an English medical treatise of the seventeenth century or in Mrs. Mather’s dream. She had perhaps heard it talked about, if not seen it used, at a long-since-forgotten birth.

There is symbolic fitness in the use of new-laid eggs. They were not only served to the mother as food but soon after birth were applied externally, first having been stirred over hot embers in an earthen pipkin, then plastered on a dressing.9 Most of the midwife’s supplies were probably as ordinary. Matthew Patten purchased or borrowed butter immediately before each of his wife’s deliveries. This may have been coincidental, but probably was not. Fresh butter, with less savory emollients like hog’s grease, was used to lubricate the midwife’s hands and to anoint the vagina and perineum to facilitate stretching during labor.10 For the parturient woman, there was comfort as well as reassurance in familiar things.

But an even more important source of aid came from the attendants themselves. Recent studies of the psychology of birth have shown the significance of emotional support during labor. An informed and empathetic coach is an effective analgesic in helping a woman surmount fear and pain.11 In delivery there was physical as well as emotional intimacy among the women. A mother might give birth held in another woman’s lap or leaning against her attendants as she squatted on the low, open-seated “midwife’s stool.”12 In cases of extreme difficulty a draught of another mother’s milk was considered a sure remedy.13 The presence in the room of a lactating woman was useful for another reason as well. A friend or neighbor was probably the baby’s first nurse, since the mother’s own milk (or colostrum) was presumed impure for several days owing to the “commotions” of birth.14

Because the attending women would watch the child grow to maturity, they also represented a kind of insurance that nothing would go wrong in delivery that might result in trouble after. A whole collection of superstitions surrounded the handling of the umbilical cord. It must not touch the floor lest the child grow up unable to hold water. It must not be cut too short for a boy, lest he prove “insufficient in encounters with Venus,” nor too long for a girl, lest she become immodest.15 Delivery was characterized by a succession of gender-infused rituals.

Childbearing in seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century New England differed from today’s community-centered home birth not only in the exclusion of males and in the intimacy with the natural world, but in the attitude toward suffering. “Natural” birth in the premodern world was presumed to be both painful and dangerous—as God intended.16 Pious women like Anne Bradstreet of Andover or Sarah Goodhue of Ipswich wrote spiritual testaments as they faced childbirth, just as men of the same class and time signed wills before embarking on a long sea journey or military expedition.17 A manuscript record kept by John Cotton of Hampton, New Hampshire, and passed on to his son-in-law, Nathaniel Gookin, shows this theme in two generations of Anne Bradstreet’s descendants.

Anne Lake Cotton gave birth to nine children in the twenty years between September 1687 and January 1707. Although she lost her first baby two months before the birth of her second, the next five children survived infancy. Then in quick succession she lost three babies at or soon after delivery. The first of these three children was born on Tuesday and died on Saturday before his expected christening on Sunday. “The name design’d was Samuel,” his father wrote, “in remembrance of Gods hearing prayers for his mother, who was wonderfully delivered of him after II convulsion fits.… God grant his Mercy herein may never be forgotten, tho Samuel be gone to the land of Forgetfullness!”18

Mrs. Cotton was apparently suffering from eclampsia, a severe form of toxemia characterized by dangerous elevation of blood pressure. With modern prenatal care this condition seldom develops to the state of convulsions today, but should it do so, the danger is extreme. Although mothers have been known to recover after as many as two hundred “fits,” the prognosis for the infant is grim. Even in relatively recent times perinatal mortality has been as high as forty-five percent.19 Little Samuel’s death is not surprising.

Dorothy, the oldest Cotton daughter, was ten years old when the first of three doomed siblings was born. When the last dead fetus was buried in the garden behind the house, she was thirteen. Just four years later she married Nathaniel Gookin and within nine months was delivered of her own first son. By any statistical standard her childbearing record was remarkable. In twenty-three years she gave birth to thirteen children, losing only one premature baby at birth. But she must have carried into her childbearing years the memory of her mother’s suffering. Ten of the twelve entries in her husband’s handwriting record some variant of the proverbial “long and dangerous travail.”

According to the family record, Dorothy Gookin experienced “exceeding hard & Dangerous Travail,” “very long Travail,” “very sharp (tho’ not long) Travail,” “hard Travail,” “very hard Travail,” and “very hard & dangerous travail.” With her ninth child she “fell in Travail and was under very Dangerous Circumstances But it pleased God [in] his Great Mercy to Spare her.” Despite these recurrent crises, she outlived her husband, who died the very month their last child was born. The thirteenth entry is in the handwriting of their oldest son: “Saturday Aug. 10, 1734 between 9 & 10 in the Morning after a long & dangerous travail My Mother was delivered of a son.”20

In historical documents the nature of “travail” is almost always a subjective impression reported by women and recorded by men. Childbirth was not only an emblem of the suffering of Eve—it was a moment of supreme drama. One need not diminish in any way the actual suffering of women to recognize that the expected pain and trial were also a source of attention and sympathy. In the drama of childbirth, husbands were twice removed from the scene. Their sex excluded them not only from direct participation but in a very real sense from active support. In the early stages they ran errands, summoning the midwife and getting supplies, but at the height of the crisis their only real calling was to wait. This is apparent in the diary of Nicholas Gilman of Exeter, New Hampshire, who recorded the events surrounding the birth of his fifth child in September of 1740.

After the Women had been Some time assembled I went out to get a little Briony Water—Upon My return My Wives mother came to me with tears in her Eyes, O, says she, I dont know how it will fare with your poor wife, hinting withal her extreme danger.21

Not only the birth itself but the husband’s very awareness of the progress of the birth was controlled by the women in the delivery room.

The diary of Matthew Patten, a farmer of Bedford, New Hampshire, is much more matter-of-fact than Gilman’s, yet even his laconic entries reveal a similar management of events. “My wife was Delivered Safe of a Daughter precisely at 12 o Clock at noon after abundance of hard Labor and a great deal of Discouragement and fear of Deficulaty,” he wrote, adding, “My Wife and the Women were all a great Deal Discouraged.”22 Momentarily at least, childbirth reversed the positions of the sexes, thrusting women into center stage, casting men in supporting roles.

Christ had likened his own death and resurrection to the sorrow and deliverance of a woman whose “time had come.”23 Travail, the curse visited by God upon the daughters of Eve, was not only an emblem of weakness and sin but a means of redemption. Joy permeated the birth record of Mary Cleaveland of Chebacco Parish in Ipswich, who recorded the birth of each child in her own shaky and unformed hand. “[T] he Lord apeard for me and maid me the liveing mother of another liveing Child,” she wrote in October of 1751. For her the entry was formulaic. After the birth of her seventh child she wrote, “The Lord was better to me than my fears.”24 So he must have been to more than one woman in northern New England. Bolstered by scriptures and sustained by their sisters, they labored and overcame.

In no other experience in the premodern world were women so completely in control or so firmly bonded. But it would be a mistake to see early American childbirth as entirely independent of male authority. Two men—the minister and the physician—were at least potential intruders into this female milieu. By the end of the eighteenth century, medical involvement in childbirth would be common in cities, foretelling the “modernization” which would eventually banish the midwife. Before 1750 the authority of the women was secure, though there are telling glimpses of what would come in the activities of two northern New England ministers, men who combined scientific and religious authority.

The most dramatic example of ministerial interest in childbirth comes from the period just after the Antinomian controversy in Massachusetts. In the 1640s, when the two chief female dissenters in the colony, Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, both gave birth to “monsters,” ministers and public officials were quick to see the judging hand of God. Little wonder that a scientifically curious minister like John Fiske of Wenham would want to examine an “unnatural birth” reported to him. In 1647, in the presence of three women, he performed a partial autopsy on the body of a stillborn infant, a process which he carefully described in his journal, detailing the opening of the skull and the examination of the “brains, fibres, and blood.”25 He decided that the fetus was basically normal but had been damaged in birth. What had brought him to this home? The fears of the mother? The suspicions of the attending women? Or simply neighborhood gossip? In this case the reason for his visit is less important than the authority which he carried. Learning—the formal book-learning which was denied to women—brought him to the home of the mother. His role here was not to officiate at a birth but to interpret it.

Hugh Adams, physician and minister in Durham, New Hampshire, three-quarters of a century later, went further. Adams, an eccentric who was eventually ousted from his parish, wrote a self-serving memoir after his dismissal in which he claimed to have assisted at the birth of Mary Glitten’s first child in December of 1724. According to Adams’ account, the woman had been in labor three and one-half days when the midwife, Madame Hilton, summoned him. He rode the seven miles to Exeter, carrying both medicine and the authority of Christ. He began with a prayer, pleading the promise of I Timothy “that the woman shall be saved in child bearing.” He then gave her “some of the most strong Hysterick medicines to recall and quicken her labour pains; and Dilated the passage of nature with Unguentum Aperitivum meipsum.” That failing, he cried unto Christ and then “proceeded by manual operation” to “move the Babe into a capable posture.” Within a minute it was born. Having facilitated the child’s first birth, Adams then officiated at its second, baptizing it with the name of Benjamin.26

It is astonishing to think of the Reverend Mr. Adams, whose obstetrical knowledge consisted of reading a few English treatises, walking into the midwife’s house in Exeter and working a medical miracle, especially one which involved complex manipulation of the fetus, a procedure hardly mastered without practice. There is no way of knowing exactly what happened, but it is clear from the minister’s own account that he considered his efforts on behalf of Mrs. Glitten one with the other “remarkable providences” described in his memoir. These included calling down the vengeance of the Lord upon the Jesuit missionary Father Rale, as well as protecting his own sons’ lives in battle by the ritual blowing of animal horns. Adams believed that melodious psalm-singing (an eighteenth-century innovation opposed by conservatives) was a direct cause of the success of New Hampshire troops against the Indians!27 It is difficult to know whether his mind-set was that of an eighteenth-century man of science or a seventeenth-century wizard. According to his own account, Adams delivered one other baby. Although the mother survived, the child did not.28

Two deliveries hardly constitute an obstetrical practice, and we might dismiss Adams’ story if it were not so instructive. His success in the case of Mary Glitten can probably be credited to the encouragement of English medical treatises, his own authority as a man of God, a remarkably inflated ego, and luck. But it is also a reminder of the power of the “learned man” in this society. In a moment of extreme peril the traditional experience of the midwife gave way to the book-learning and professional aura of the minister-physician.

In the development of obstetrics in northern New England, Hugh Adams of Durham stands midway between a scientifically curious minister like John Fiske and a professional physician like Edward Augustus Holyoke of Salem, who by 1755 was regularly consulted in cases of “hard labor.”29 The rapid development of forceps in the second half of the eighteenth century gave the physician a technological advantage he had not had before. By 1800 “male science” had diverged dramatically from “female tradition” and midwifery was under strenuous attack.30

But the decline of the midwives in the nineteenth century cannot be attributed solely to the development of obstetrical science. It was also a consequence of the undermining of traditional social relations and the increasing privatization of the family.31 Midwives were “experienced,” whereas physicians were “learned.” Because the base of the midwives’ experience was shared by all women, their authority was communal as well as personal. In attacking the midwives, nineteenth-century physicians were attacking a system more than a profession. The very intensity of their disdain for “old wives’ tales” suggests the continuing authority of the women even in this period of dramatic change.32

The diary of Mary Holyoke, whose industrious housekeeping we surveyed in Chapter 4, gives some glimpses of childbearing customs in Augustus Holyoke’s own family. Holyoke’s long interest in obstetrics may have been stimulated by the death of his first wife in childbed. The recurring trauma of his second marriage was not “hard labor,” however, but infant death. Mary Holyoke gave birth to twelve children in twenty-two years, only four of whom survived infancy. Her first little Polly lived four years, her second ten months, and her third, christened for her older sisters on the fifth of September 1767, died four days later. Five other infants died in the first weeks or months of life. One after another, the “dear babies” came and went, while Mary continued to garden, write in her journal, sew cravats for the Doctor, and take tea with friends.33

She summarized each delivery in the simple phrase “brought to bed,” seldom adding any other details. On September 12, 1771, she was “Brought to Bed quite alone 11 A.M. of a Daughter.” Was she literally alone in her house, without the assistance of her husband, a maid, or a midwife? Or was she simply implying that no one from outside the family had arrived in time for the birth? For five of the twelve deliveries she did list the names of two or three women who were with her. “Mrs. Jones” was present at four births, “Mrs. Mascarene” (who was Augustus’ sister Peggy) at three, and “Mrs. Carwick” at two.34 No assemblage of the neighborhood is implied here, just an intimate circle of relatives and friends. There are two explicit references to her husband’s ministration near the time of birth. Three days before one baby arrived, “the Doctor” bled her. Two months after the birth of another, when she developed a breast infection, he lanced it. Medical assistance did not banish traditional comforts, however. When Mary developed a “knot” in her breast a few days after the birth of her ninth child, “Nurse anointed it with Parsley, wormwood & Camomel Stewed in Butter.”35

The diary suggests that in urban Salem, as elsewhere in New England, childbirth remained a central event in the community of women. Mary noted in her diary when her friends were “brought to bed,” but among these women a formal “sitting up week” seems to have replaced the hasty gathering in the night still characteristic of rural neighborhoods. On March 3 Mary herself “kept chamber” and the next day was “Brought to bed of Peggy.” Two weeks later, when she was ready to sit in a chair and chat, the visits began. On Sunday one friend came, on Monday five, on Thursday two, and during the following week eight more.36 These women sipped tea and admired each other’s gifts, including perhaps a fancy pincushion stuck with the baby’s initials or the motto “Welcome Little Stranger.”37 The circle of female support had begun to shrink as the intimate ritual of birth gave way to a more distant ceremony of welcome.

FOR MOST WOMEN, life in the childbearing years was less firmly bound by the agricultural seasons than by personal seasons of pregnancy and lactation, twenty-to-thirty-month cycles which stretched from the birth of one baby to the birth of the next. The “travail” of birth was preceded by the “travail” of pregnancy.

Twentieth-century women would recognize some aspects of seventeenth-century prenatal care. Missing from premodern guides to pregnancy was any reference to weight control, but there were remedies for other common problems. For swelling of feet and ankles, The Experienced Midwife offered a lotion of vinegar and rosewater; for pressure pain, it suggested an improvised and probably uncomfortable version of a maternity corset, swathing bands looped around the abdomen and tied at the neck. It had little to say about the most famous of female complaints—morning sickness—though it did note that nausea was a possible sign of pregnancy.38

Court records suggest that daily life continued with little interruption for pregnancy. At the same time, they make it clear that pregnant women were endowed with a special status entitling them to deference and protection. The case of Sarah Boynton of Haverhill is instructive. She was probably in her fourth month when Ebenezer Browne came to her yard looking for an ox which her husband had locked up. Sarah ordered Browne off their ground, telling him, “If you will come, you must take what comes, for I will do what I can to hinder you.” Browne retorted, “If you were a man as you are a woman I would stave out your braines.” Not to be intimidated, she thrust a ladder against the door of the hovel where the animal was kept. When Browne grabbed it and threw it down, the uppermost rung struck her.39

In March, Sarah Boynton’s husband successfully sued for damages, claiming that his wife, being pregnant, had suffered great pain from her injuries, had been unable to do her work for twenty-six weeks, and had required expensive advice from midwives. Although Sarah Boynton clearly felt it her duty to defend her husband’s right to the ox, her pregnancy notwithstanding, her frailness became a key point of the damage claim in court. Ebenezer Browne knew he should not strike a woman, yet he did. His taunt, “If you were a man as you are a woman,” implied that Sarah had stepped beyond the bounds which he would tolerate in a male, as though in abandoning feminine weakness she had invited attack. The court, in this case, did not agree.

But what were the limits of male protectiveness? And what was the responsibility of the woman herself for her own health and that of her child? Margaret Prince of Gloucester said she “was as lusty as any woman in town” before William Browne began to trouble her, dropping veiled threats, calling her “one of Goodwife Jackson’s imps,” and warning her that the formal complaint she had lodged in court would be the dearest day’s work she ever made. She had a difficult delivery and her child was stillborn. In her mind the case was clear: Browne was responsible for the death of her child.40 She probably implied witchcraft, though not necessarily. Midwifery manuals warned newly pregnant women to avoid all unusual worries and anxieties for the good of the child.41 In attacking the psychological health of the mother, Browne attacked the baby.

Yet two neighbors, Goody and Goodman Kettle, argued in Browne’s defense that there were much more apparent reasons for Margaret Prince’s troubles. Not three weeks before her travail they had seen her carrying clay to her house in a bucket on her head. What is more, she had “reached up over the door to daub with clay.”42 They were undoubtedly referring to a folk belief (still held by some women in the middle of the twentieth century) that reaching over one’s head in the last months of pregnancy would result in a tangled umbilical cord and the possible death of the child. Goody Kettle said that she had walked home with her neighbor and told her “she did wrong in carrying clay at such a time, but Goody Prince replied that she had to, her husband would not, and her house lay open. She had carried three pails and had three more to carry.”43

Here was a woman caught between two imperatives—to preserve the safety of her unborn child and to finish her house. Perhaps her behavior was a kind of demonstration of desperation, an appeal for help. She apparently got none. Goody Kettle could offer advice, but, without ignoring her own precepts, she could not offer physical assistance because she herself was pregnant.44 Angry at her husband, Margaret Prince violated folk wisdom, then turned her anguish at the loss of her child toward William Browne, a troublesome and disrespectful neighbor. Although her husband (perhaps experiencing some guilt of his own) concurred in the accusation, the court was not convinced and the Princes lost their suit.

Because such cases are isolated, they admit only tentative impressions. Yet the kind of conflict Margaret Prince and Sarah Boynton exemplify may have been frequent among women of ordinary status and small means. Folk proscriptions on lifting helped to curb what might have become a dangerous workload in this labor-poor society. Yet, regardless of status, a woman could afford to be pampered only in proportion to the number of other persons available to do her work.

For a gentlewoman, like Mary Gilman of Exeter, relatives and servants might prove as much an added burden as a help. In the spring of 1740 the Gilman family included four children ranging in age from eighteen months to eight years. Mary’s mother lived with them, as did a teen-aged cousin, Molly Little. Nicholas’ parents and several unmarried sisters lived nearby. Despite all this potential help, it is doubtful if Mary Gilman had much time to put up her feet during the last five months of her fifth pregnancy. One after the other, over a two-month period all four children contracted measles, followed by Molly Little herself. Meanwhile Mary’s mother was called away to Newbury to the bedside of a dying father, and Nicholas’ mother was totally absorbed in nursing one daughter who was dying and another who was chronically ill. Mary herself took a turn watching her sisters-in-law at night. Nicholas was absorbed with his own spiritual and professional problems. Between bouts of headache and toothache he prepared sermons, spending two to three days a week in his new pastorate of Durham, fifteen miles away. Except for one brief entry noting that Mary herself had broken out with a rash, he never mentions her health in the diary. The first evidence of her pregnancy is the announcement of the birth of a son in September.45

Through such records we can barely glimpse the routines, shared anxieties, and supporting female lore which characterized the “nine months travail” which preceded the birth of each child.

“DAUGHTER BEGINS to suckle her little Molly; God make her a good nurse,” Benjamin Lynde of Salem wrote in his diary four days after the birth of his first grandchild. Lynde reflected a common attitude in New England—nursing one’s own children was both a blessing and a duty.46 An ordinary woman had no choice, of course, since the only alternative was to hire another mother to do it for her. For all classes in northern New England, maternal breast-feeding was the norm.47

Mothers nursed in public as well as in private, sitting on the ground outside the village church as well as at home in their own beds—with or without the presence of visitors.48 Young mothers learned by observation as well as by explicit instruction how to deal with cracked nipples, sleepy infants, and insistent toddlers. They probably also learned a medley of techniques lost to their more fastidious descendants, including the use of puppies to relieve engorged breasts. At some point they discovered that suckling “suppressed the terms.”49 Whether or not they consciously relied upon this ancient method of contraception, they tuned their lives to the natural rhythms of the reproductive cycle.

That those rhythms did indeed shape female life becomes apparent if we look closely at the reproductive histories of three eighteenth-century women as reflected in their husbands’ diaries. Although male diarists seldom wrote about their wives, they did consistently record those female activities which disrupted or affected their own. Simply by correlating the two events most consistently mentioned—births and overnight journeys—one can derive circumstantial, though impressive, evidence of the personal meaning of fertility.

The diaries of Zaccheus Collins, Matthew Patten, and Joseph Green cover large portions of the years of childbearing for each of their wives—fifteen out of seventeen years for Mrs. Green, eighteen out of twenty-one years for Mrs. Patten, and twenty out of twenty-two years for Mrs. Collins.50 The three families were not only prolific but unusually healthy, exemplifying premodern reproductive patterns in an almost ideal form, with birth intervals averaging twenty-two, twenty-three, and twenty-five months. Elizabeth Collins and Elizabeth Patten each gave birth to eleven children. Elizabeth Green was expecting her ninth child at the time of her husband’s death.

The diary of Joseph Green begins in 1700, soon after his call to the ministry in Salem Village, now Danvers, Massachusetts. That of Zaccheus Collins, a Quaker farmer of Lynn, Massachusetts, opens in 1725, while that of Matthew Patten, a founder of the Scotch-Irish community of Bedford, New Hampshire, begins in 1754. In comparison to their husbands, all three wives led sheltered and narrow lives, though each traveled—in her own way and according to her own seasons. As might be expected, Elizabeth Collins, the Quaker, traveled most frequently, sometimes accompanying itinerant Friends who were passing through Lynn on their way to nearby meetings. Mrs. Patten, who lived in an isolated and, in its early stages, frontier community, traveled least. Yet the journeys of all three women fall into a remarkably consistent pattern when keyed to their reproductive histories.

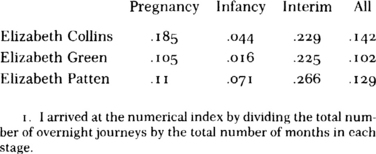

For purposes of analysis, the overnight journeys of the three wives can be divided into three periods: a period of “Pregnancy,” beginning 280 days before the birth of each child; a period of “Infancy,” from birth to ten months; and an “Interim” period, a variable span from ten months after the birth of the last child to 280 days before the birth of the next. (See Table 4.) For all three women, the greatest frequency of travel was in the so-called “Interim” period. For two of the three women, “Infancy” was clearly a more serious restraint than “Pregnancy.” To grasp the significance of these rather limited facts, we must look at each period in greater detail.

It is hardly surprising that pregnancy restrained travel. What is surprising is the number of times all three women undertook journeys in the middle trimester. The most adventuresome trip Elizabeth Patten ever took was during the fifth month of her tenth pregnancy when she went by horseback alone the more than eighty miles to Boston to sell cloth and thread. Matthew, who was usually responsible for such ventures, was heavily involved in harvesting at the time.51 Elizabeth Collins took a number of journeys early in the sixth month of pregnancy. In March of 1731 she spent almost two weeks in Haverhill and Newbury, presumably visiting relatives. In April of 1741 Zaccheus took her and her sister-in-law to Boston, returning for them three days later.52 Elizabeth Green completed two journeys in the seventh month, both of them to nearby Wenham, where her parents lived. Joseph’s diary entry for June 8, 1710, is quite explicit about the fact that they shared a horse.53

Table 4. Incidence of Travel During Pregnancy and Lactation1

All three women, however, remained close to their homes during the last two months of each pregnancy. This seems to have been true even when unusual circumstances might have impelled them to travel. Late in September of 1755 Elizabeth Patten remained in Bedford while her husband attended her own father’s funeral in nearby Londonderry. She was just one month away from the delivery of her fourth child.54 Pregnancy may have been a “nine month sickness” as the midwifery manual said, but these women were slow to succumb. A more dramatic restraint on travel is apparent in the next period—the first ten months of each baby’s life. This is undoubtedly related to lactation, which in many ways placed more demands on the mother than pregnancy. Although a woman might leave her infant for a short while, perhaps relying for an occasional feeding upon a neighbor who was also nursing, she could not travel far or long without taking the child with her. Mrs. Green and Mrs. Patten occasionally traveled with infants (James Patten was baptized in Londonderry, New Hampshire, at the age of seven months while his parents were visiting there).55 But all three mothers avoided traveling during the third quarter of their child’s first year. One reason is obvious. Compared with a newborn infant, a baby seven or eight months old is simply not very portable, being both heavier and more active. If he or she were still dependent upon mother’s milk, the only practical solution was to stay home.

But for all three women, the most significant pattern is not the restraint on travel during pregnancy and infancy but the sudden jump in activity after the tenth month of each baby’s life. For Elizabeth Collins, this is especially dramatic. For six of the nine babies mentioned in the diary, her first journey after birth was between ten and fifteen months. For the other babies, the second journey after birth fell into this same crucial period. A similar pattern is discernible for Mrs. Green. The timing suggests some connections with weaning, a possibility confirmed in Joseph Green’s diary entry for April 12, 1702. Green noted that on this day he took his wife to her parents’ home in Wenham, then “came home to wean John,” who was then seventeen months old.56

There is supporting evidence in less-detailed diaries of the period for the idea of the “weaning journey.” From January 1740, when Nicholas Gilman began his daily diary, until late in August of 1741, his wife, Mary, apparently never left Exeter, New Hampshire, where they lived. This period included the last eight months of her fifth pregnancy and the first year of their son Josiah’s life. But just before Josiah’s first birthday she took an unexplained three-day journey alone to her grandmother’s home in Newbury, Massachusetts.57 There is a similar example in the almanac diary of Edward Holyoke of Salem. In January of 1730 his wife made a two-week visit to her parents’ home in Ipswich. Their child was then sixteen months old.58 The evidence is circumstantial but suggestive.

Supposing New England mothers did leave home to wean their babies, what might this mean? Did maternal absence mean abrupt and traumatic weaning? Was it a manifestation of a repressive and potentially pathological approach to child care? Some historians might argue that it did. Noting the pervasiveness of oral themes and anxieties in the historical record of New England witchcraft, John Demos has speculated that “many New England children were faced with some unspecified but extremely difficult psychic tasks in the first year or so of life.”59 James Axtell has pointed to John Winthrop’s simile for his own conversion: “I became as a weaned child. I knew I was worthy of nothing for I knew I could doe nothing for my self.”60 Certainly the sudden disappearance not only of the breast but of the mother herself might present severe difficulties for the infant.

Yet the Winthrop quotation cuts in two directions. It documents the child’s sense of loss, but it does so from the parent’s point of view. Discounting the unlikely possibility that John Winthrop remembered his own weaning, we find him describing the feelings of the child as he perceived them from the outside. The situation he described may indeed document parental harshness, but the description of the situation suggests considerable empathy. Winthrop did not focus upon the behavior of the child, its crying or its demands for its mother, but upon his perception of its interior state, its feeling of helplessness.

Now, the really crucial problem for our purposes is the response of parents to this perceived state. How can parents who understand and sympathize with a child’s need deliberately deny it? As the scripture says, “What man is there of you, whom if his son ask bread, will he give him a stone?” Setting aside for the moment unconscious motives, we can say that loving parents will deny a child’s need for only two reasons: either they lack the ability to satisfy it or they believe that denial will result in long-term good. In the crisis of weaning, mothers and fathers were obviously in quite different positions because one could supply the demand, one could not. Assuming that in colonial America both parents believed that rather sudden weaning was for the ultimate benefit of the child, the withdrawal of the mother made perfectly good sense.

This would be especially so if the parent who could supply the need might be tempted to do so. In the words of an eighteenth-century Maine minister, the converted Christian learned that Christ was “as willing to feed him with his Flesh and Blood; as ever Tender Mother was to draw out her full & aking Breast to her hungry, crying child.”61 Abrupt or sudden weaning would be as painful for the mother as it was difficult for the child. The discomfort would be both physical and psychological, as the mother thwarted both the impulse to relieve her breasts and the desire to nurture her crying child. This denial of the maternal role may well have reduced her to the state of psychic helplessness characteristic of a weaned child. Hence her own trip home to mother.

The facts fit together neatly—rather too neatly perhaps. Although there is circumstantial evidence for a more widespread practice, there is only one fully documented example of a “weaning journey” in the diaries under investigation—that of Elizabeth Green, who remained at her parents’ home in Wenham in the spring of 1702 while her husband returned home to wean sixteen-month-old John. Even this event can have more than one interpretation. On the one hand, the mother’s journey can be seen as a drastic measure, an abrupt and psychologically disturbing end to infancy. On the other hand, at sixteen months little John might already have shown clear independence and a loss of interest in the breast. Nursing may have been confined to one or two brief feedings, perhaps at night or in the early morning when it was easier for the mother to bring him to bed than get up and prepare other food. The journey of the mother may have been simply the ritual termination of an already waning stage, an experience made more pleasant for both mother and child by the active interest and involvement of the father.

Yet disturbing questions remain. If the stage of weaning was not marked with anxiety and potential conflict, why did the mother find it necessary to leave? Was she in fact acting counter to her own instincts? Did Joseph Green’s diary entry mark the eventual triumph of a husband over the prolonged, and to him perhaps disturbing, intimacy of mother and child? Or was it that Mrs. Green simply did not trust her own resolve? Did she believe herself incapable of surmounting that “softness,” that excessiveness of maternal affection so mistrusted by ministers? Was her dependence on John perhaps an even greater issue than his dependence on her? Little matter, perhaps, for within a few months there would be another infant in the house and the whole cycle would begin again.

PREGNANCY, BIRTH, LACTATION—these three stages in the female reproductive cycle established the parameters of life in the childbearing years. One need not exaggerate their importance or describe women in bondage to the curse of Eve to recognize that these personal seasons might shape the smallest details of daily life—when to lift a heavy wash kettle or daub the chinks of a house, how far to go from home in quest of butter or yarn, whether to travel to Newbury meeting, mount a neighbor’s horse for a trip to Boston, or stay at home and brew beer. Each cycle of reproduction was marked by epicycles, recurring patterns of restraint and release, pain and deliverance, sorrow and celebration. All of these were summarized in the word travail, a term which connoted not simply pain but effort, especially strenuous or self-sacrificing effort.

“O my children all, which in pains and care have cost me dear,” Sarah Goodhue began a long passage of advice to her offspring. In The Four Ages of Man Anne Bradstreet put a more detailed description of maternal effort into the mouth of a child.

With tears into the world I did arrive,

My mother still did waste as I did thrive,

Who yet with love and all alacrity,

Spending, was willing to be spent for me.

With wayward cryes I did disturb her rest,

Who sought still to appease me with the breast:

With weary arms she danc’d and By By sung,

When wretched I ingrate had done the wrong.62

Eve’s badge of sorrow might reinforce cultural notions of the weakness or vulnerability of women, but it might also become an instrument of female power. Suffering in childbirth could arouse the sympathy and protective instincts of husbands, but, even more profoundly perhaps, the prolonged sacrifices of pregnancy, birth, and lactation might convince religious children of their mother’s claims upon them.

In 1701 Samuel Sewall of Boston stood in tearful elegy beside the grave of his mother, one of the first settlers of Newbury, Massachusetts. “My honoured and beloved Friends and Neighbours!” he exclaimed. “My dear Mother never thought much of doing the most frequent and homely offices of Love for me; and lavish’d away many Thousands of Words upon me, before I could return one word in Answer.”63 Sewall spoke of his mother’s piety and her industry, but the focus of emotion for this grown man was clearly his own infancy. Spending herself in childbearing, Mistress Sewall had earned the devotion of her son.