3.1 From Physical Problems to Two-Dimensional Tensor Networks

3.1.1 Classical Partition Functions

Partition function, which is a function of the variables of a thermodynamic state such as temperature, volume, and etc., contains the statistical information of a thermodynamic equilibrium system. From its derivatives of different orders, we can calculate the energy, free energy, entropy, and so on. Levin and Nave pointed out in Ref. [1] that the partition functions of statistical lattice models (such as Ising and Potts models) with local interactions can be written in the form of TN. Without losing generality, we take square lattice as an example.

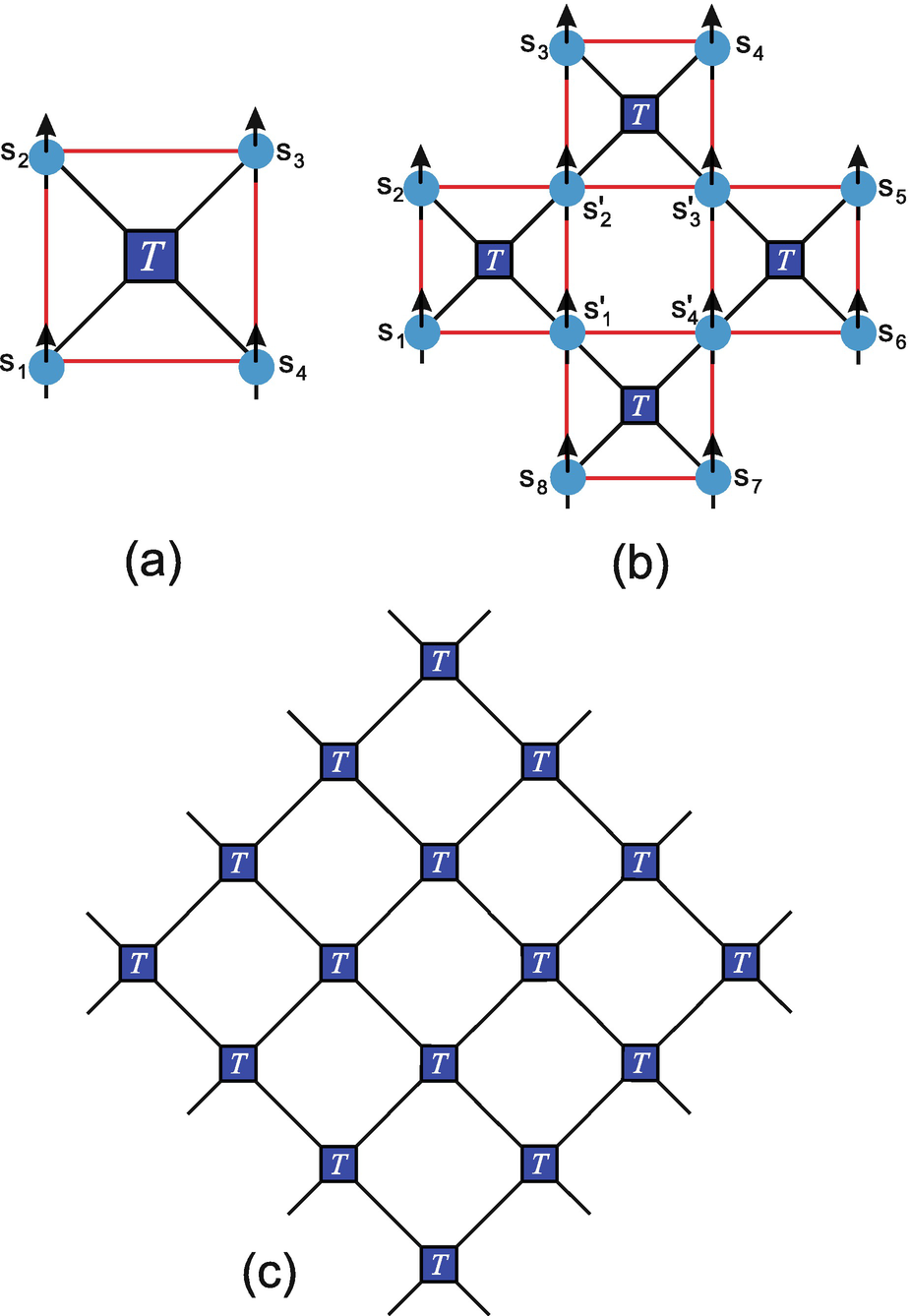

(a) Four Ising spins (blue balls with arrows) sitting on a single square, and the red lines represent the interactions. The blue block is the tensor T (Eq. (3.2)), with the black lines denoting the indexes of T. (b) The graphic representation of the TN on a larger lattice with more than one square. (c) The TN construction of the partition function on infinite square lattice

if they refer to the same Ising spin. The graphic representation of Eq. (3.6) is shown in Fig. 3.1c. One can see that on square lattice, the TN still has the geometry of a square lattice. In fact, such a way will give a TN that has a geometry of the dual lattice of the system, and the dual of the square lattice is itself.

if they refer to the same Ising spin. The graphic representation of Eq. (3.6) is shown in Fig. 3.1c. One can see that on square lattice, the TN still has the geometry of a square lattice. In fact, such a way will give a TN that has a geometry of the dual lattice of the system, and the dual of the square lattice is itself.For the Q-state Potts model on square lattice, the partition function has the same TN representation as that of the Ising model, except that the elements of the tensor are given by the Boltzmann weight of the Potts model and the dimension of each index is Q. Note that the Potts model with q = 2 is equivalent to the Ising model.

on each bond and put on each site a super-digonal tensor I (or called copy tensor) defined as

on each bond and put on each site a super-digonal tensor I (or called copy tensor) defined as

3.1.2 Quantum Observables

and 〈ψ|ψ〉 are the contraction of a scalar TN, where

and 〈ψ|ψ〉 are the contraction of a scalar TN, where  can be any operator. For a 1D MPS

, this can be easily calculated, since one only needs to deal with a 1D TN stripe. For 2D PEPS

, such calculations become contractions of 2D TNs. Taking 〈ψ|ψ〉 as an example, the TN of such an inner product is the contraction of the copies of the local tensor (Fig. 3.1c) defined as

can be any operator. For a 1D MPS

, this can be easily calculated, since one only needs to deal with a 1D TN stripe. For 2D PEPS

, such calculations become contractions of 2D TNs. Taking 〈ψ|ψ〉 as an example, the TN of such an inner product is the contraction of the copies of the local tensor (Fig. 3.1c) defined as

. There are no open indexes left and the TN

gives the scalar 〈ψ|ψ〉. The TN for computing the observable

. There are no open indexes left and the TN

gives the scalar 〈ψ|ψ〉. The TN for computing the observable  is similar. The only difference is that we should substitute some small number of

is similar. The only difference is that we should substitute some small number of  in original TN of 〈ψ|ψ〉 with “impurities” at the sites where the operators locate. Taking one-body operator as an example, the “impurity” tensor on this site can be defined as

in original TN of 〈ψ|ψ〉 with “impurities” at the sites where the operators locate. Taking one-body operator as an example, the “impurity” tensor on this site can be defined as ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \widetilde{T}_{a_1a_2a_3a_4}^{[i]} = \sum_{s,s'} P_{s,a^{\prime\prime}_1a^{\prime\prime}_2a^{\prime\prime}_3a^{\prime\prime}_4}^{\ast} \hat{O}_{s,s'}^{[i]} P_{s',a_1^{\prime}a_2^{\prime}a_3^{\prime}a_4^{\prime}}. \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ10.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{\langle \psi| \hat{O}^{[i]}|\psi \rangle}{\langle \psi| \psi \rangle} = \frac{\text{tTr }\ \widetilde{T}^{[i]} \prod_{n\neq i} T}{\text{tTr }\ \prod_{n=1}^{N} T}. \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ11.png)

![$$\langle \psi | \hat {O}^{[i]} \hat {O}^{[j]} |\psi \rangle $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq8.png) is nothing but adding another “impurity” by

is nothing but adding another “impurity” by ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \langle \psi| \hat{O}^{[i]} \hat{O}^{[j]} |\psi \rangle = \text{tTr }\ \widetilde{T}^{[i]}\widetilde{T}^{[j]} \prod_{n\neq i,j}^{N} T. \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ12.png)

3.1.3 Ground-State and Finite-Temperature Simulations

The first way can be realized by, e.g., Monte Carlo methods where one could randomly change or choose the value of each tensor element to locate the minimal of energy. One can also use the Newton method and solve the partial-derivative equations ∂E∕∂x

n = 0 with x

n standing for an arbitrary variational parameter. Anyway, it is inevitable to calculate E (i.e.,  and 〈ψ|ψ〉) for most cases, which is to contraction the corresponding TNs as explained above.

and 〈ψ|ψ〉) for most cases, which is to contraction the corresponding TNs as explained above.

We shall stress that without TN , the dimension of the ground state (i.e., the number of variational parameters) increases exponentially with the system size, which makes the ground-state simulations impossible for large systems.

The second way of computing the ground state with imaginary-time evolution is more or less like an “annealing” process. One starts from an arbitrarily chosen initial state and acts the imaginary-time evolution operator on it. The “temperature” is lowered a little for each step, until the state reaches a fixed point. Mathematically speaking, by using Trotter-Suzuki decomposition, such an evolution is written in a TN defined on (D + 1)-dimensional lattice, with D the dimension of the real space of the model.

containing the on-site and two-body interactions of the n-th and n + 1-th sites. It is useful to divide

containing the on-site and two-body interactions of the n-th and n + 1-th sites. It is useful to divide  into two groups,

into two groups,  as

as

or

or  commutes with each other. Then the evolution operator

commutes with each other. Then the evolution operator  for infinitesimal imaginary time τ → 0 can be written as

for infinitesimal imaginary time τ → 0 can be written as ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \hat{U}(\tau) = e^{-\tau \hat{H}} = e^{-\tau \hat{H}^e} e^{-\tau \hat{H}^o} + O\left(\tau^2\right) \left[\hat{H}^e, \hat{H}^o\right]. {} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ17.png)

.

.

, satisfying

, satisfying

In addition, one can readily see that the evolution of a 2D state leads to the contraction of a 3D TN. Such a TN scheme provides a straightforward picture to understand the equivalence between a (d + 1)-dimensional classical and a d-dimensional quantum theory. Similarly, the finite-temperature simulations of a quantum system can be transferred to TN contractions with Trotter-Suzuki decomposition. For the density operator  , the TN is formed by the same tensor given by Eq. (3.20).

, the TN is formed by the same tensor given by Eq. (3.20).

3.2 Tensor Renormalization Group

(see the left side of Fig. 3.2).

(see the left side of Fig. 3.2).

For an infinite square TN with translational invariance, the renormalization in the TRG algorithm is realized by two local operations of the local tensor. After each iteration, the bond dimensions of the tensor and the geometry of the network keep unchanged

These two steps define the contraction strategy of TRG. By the first step, the number of tensors in the TN (i.e., the size of the TN

) increases from N to 2N, and by the second step, it decreases from 2N to N∕2. Thus, after t times of each iterations, the number of tensors decreases to the  of its original number. For this reason, TRG

is an exponential contraction algorithm.

of its original number. For this reason, TRG

is an exponential contraction algorithm.

The dimension of the tensor at the t-th iteration becomes  , if no truncations are implemented. This means that truncations of the bond dimensions are necessary. In its original proposal, the dimension is truncated by only keeping the singular vectors of the χ-largest singular values in Eq. (3.22). Then the new tensor T

(t+1) obtained by Eq. (3.23) has exactly the same dimension as T

(t).

, if no truncations are implemented. This means that truncations of the bond dimensions are necessary. In its original proposal, the dimension is truncated by only keeping the singular vectors of the χ-largest singular values in Eq. (3.22). Then the new tensor T

(t+1) obtained by Eq. (3.23) has exactly the same dimension as T

(t).

The truncation is optimized according to the SVD of T (t). Thus, T (t) is called the environment. In general, the tensor(s) that determines the truncations is called the environment. It is a key factor to the accuracy and efficiency of the algorithm. For those that use local environments, like TRG, the efficiency is relatively high since the truncations are easy to compute. But, the accuracy is bounded since the truncations are only optimized according to some local information (like in TRG the local partitioning T (t)).

One may choose other tensors or even the whole TN

as the environment. In 2009, Xie et al. proposed the second renormalization group (SRG)

algorithm [7]. The idea is in each truncation step of TRG

, they define the global environment that is a fourth-order tensor  with T

(n, t) the n-th tensor in the t-th step and

with T

(n, t) the n-th tensor in the t-th step and  the tensor to be truncated.

the tensor to be truncated.  is the contraction of the whole TN after getting rid of

is the contraction of the whole TN after getting rid of  , and is computed by TRG. Then the truncation is obtained not by the SVD

of

, and is computed by TRG. Then the truncation is obtained not by the SVD

of  , but by the SVD of

, but by the SVD of  . The word “second” in the name of the algorithm comes from the fact that in each step of the original TRG, they use a second TRG to calculate the environment. SRG is obviously more consuming, but bears much higher accuracy than TRG. The balance between accuracy and efficiency, which can be controlled by the choice of environment, is one main factor to consider while developing or choosing the TN algorithms.

. The word “second” in the name of the algorithm comes from the fact that in each step of the original TRG, they use a second TRG to calculate the environment. SRG is obviously more consuming, but bears much higher accuracy than TRG. The balance between accuracy and efficiency, which can be controlled by the choice of environment, is one main factor to consider while developing or choosing the TN algorithms.

3.3 Corner Transfer Matrix Renormalization Group

Overview of the CTMRG contraction scheme. The tensors in the TN are contracted to the variational tensors defined on the edges and corners

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \tilde{C}^{[1]}_{\tilde{b}_2b^{\prime}_1} &\displaystyle \leftarrow&\displaystyle \sum_{b_1} C^{[1]}_{b_1b_2}R^{[1]}_{b_1a_1b^{\prime}_1}, \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ26.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \tilde{R}^{[2]}_{\tilde{b}_2 a_4 \tilde{b_3}} &\displaystyle \leftarrow&\displaystyle \sum_{a_2}R^{[2]}_{b_2a_2b_3}T_{a_1a_2a_3a_4}, {} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ27.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \tilde{C}^{[2]}_{\tilde{b}_3b^{\prime}_4} &\displaystyle \leftarrow&\displaystyle \sum_{b_4} C^{[2]}_{b_3b_4}R^{[3]}_{b_4a_3b^{\prime}_4}, \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ28.png)

and

and  .

.

The first arrow shows absorbing tensors R

[1], T, and R

[3] to renew tensors C

[1], R

[2], and C

[2] in left operation. The second arrow shows the truncation of the enlarged bond of ![$$\tilde {C}^{[1]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq30.png) ,

, ![$$\tilde {R}^{[2]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq31.png) , and

, and ![$$\tilde {C}^{[2]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq32.png) . Inset is the acquisition of the truncation matrix Z

. Inset is the acquisition of the truncation matrix Z

After the contraction given above, it can be considered that one column of the TN

(as well as the corresponding row tensors R

[1] and R

[3]) is contracted. Then one chooses other corner matrices and row tensors (such as ![$$\tilde {C}^{[1]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq33.png) , C

[4], and R

[1]) and implement similar contractions. By iteratively doing so, the TN is contracted in the way shown in Fig. 3.3.

, C

[4], and R

[1]) and implement similar contractions. By iteratively doing so, the TN is contracted in the way shown in Fig. 3.3.

Note that for a finite TN , the initial corner matrices and row tensors should be taken as the tensors locating on the boundary of the TN. For an infinite TN, they can be initialized randomly, and the contraction should be iterated until the preset convergence is reached.

CTMRG can be regarded as a polynomial contraction scheme. One can see that the number of tensors that are contracted at each step is determined by the length of the boundary of the TN at each iteration time. When contracting a 2D TN defined on a (L × L) square lattice as an example, the length of each side is L − 2t at the t-th step. The boundary length of the TN (i.e., the number of tensors contracted at the t-th step) bears a linear relation with t as 4(L − 2t) − 4. For a 3D TN such as cubic TN, the boundary length scales as 6(L − 2t)2 − 12(L − 2t) + 8, thus the CTMRG for a 3D TN (if exists) gives a polynomial contraction.

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} \sum_{b}\tilde{C}^{[1]\dagger}_{\tilde{b}b}{\tilde{C}^{[1]}}_{\tilde{b}'b} + \sum_{b}\tilde{C}^{[2]\dagger}_{\tilde{b}b}{\tilde{C}^{[1]}}_{\tilde{b}'b} \simeq \sum_{b=0}^{\chi-1} V_{\tilde{b}b} \varLambda_{b} V^{*}_{\tilde{b}'b}. {} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ29.png)

![$$\tilde {C}^{[1]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq34.png) ,

, ![$$\tilde {R}^{[2]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq35.png) , and

, and ![$$\tilde {C}^{[2]}$$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_IEq36.png) using V as

using V as ![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} C^{[1]}_{b^{\prime}_1b_2} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \sum_{\tilde{b}_2}\tilde{C}^{[1]}_{\tilde{b}_2b^{\prime}_1}V^{*}_{\tilde{b}_2b_2}, \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ30.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} R^{[2]}_{b_2a_4b_3} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \sum_{\tilde{b}_2,\tilde{b}_3}\tilde{R}^{[2]}_{\tilde{b}_2a_4\tilde{b}_3} V_{\tilde{b}_2b_2} V^{*}_{\tilde{b}_3b_3},{} \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ31.png)

![$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} \begin{array}{rcl} C^{[2]}_{b_3b^{\prime}_4} &\displaystyle =&\displaystyle \sum_{\tilde{b}_3}\tilde{C}^{[2]}_{\tilde{b}_3b^{\prime}_4} V_{\tilde{b}_3b_3}. \end{array} \end{aligned} $$](../images/489509_1_En_3_Chapter/489509_1_En_3_Chapter_TeX_Equ32.png)

Same as TRG

or TEBD

, the truncations are obtained by the matrix decompositions of certain tensors that define the environment. From Eq. (3.29), the environment in CTMRG is the loop formed by the corner matrices and row tensors. Note that symmetries might be considered to accelerate the computation. For example, one may take C

[1] = C

[2] = C

[3] = C

[4] and R

[1] = R

[2] = R

[3] = R

[4] when the TN has rotational and reflection symmetries ( after any permutation of the indexes).

after any permutation of the indexes).

3.4 Time-Evolving Block Decimation: Linearized Contraction and Boundary-State Methods

The TEBD algorithm by Vidal was developed originally for simulating the time evolution of 1D quantum models [29–31]. The (finite and infinite) TEBD algorithm has been widely applied to varieties of issues, such as criticality in quantum many-body systems (e.g., [32–34]), the topological phases [35], the many-body localization [36–38], and the thermodynamic property of quantum many-body systems [39–45].

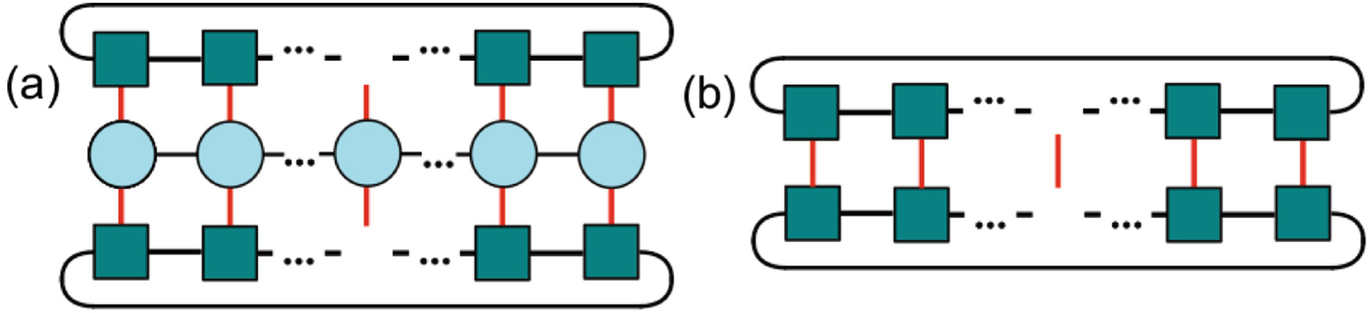

The illustration of the contraction and truncation of the iTEBD algorithm. In each iteration step, a row of tensors in the TN are contracted to the MPS, and truncations by SVD are implemented so that the bond dimensions of the MPS keep unchanged

and

and  . Meanwhile, the spectrum is also updated as

. Meanwhile, the spectrum is also updated as

It is readily to see that the number of tensors in iTEBD will be reduced linearly as tN, with t the number of the contraction-and-truncation steps and N →∞ the number of the columns of the TN. Therefore, iTEBD (also finite TEBD) can be considered as a linearized contraction algorithm, in contrast to the exponential contraction algorithm like TRG .

, for example, one defines a matrix by contracting the tensors and spectrum connected to the target bond as

, for example, one defines a matrix by contracting the tensors and spectrum connected to the target bond as

Similar to TRG and SRG , the environment of the original iTEBD is M in Eq. (3.37), and the error is measured by the discarded singular values of M. Thus, iTEBD seems to only use local information to optimize the truncations. What is amazing is that when the MPO is unitary or near unitary, the MPS converges to a so-called canonical form [46, 47]. The truncations are then optimal by taking the whole MPS as the environment. If the MPO is far from being unitary, Orús and Vidal proposed the canonicalization algorithm [47] to transform the MPS into the canonical form before truncating. We will talk about this issue in detail in the next section.

The iTEBD can be understood as a boundary-state method. One may consider one row of tensors in the TN as an MPO (see Sect. 2.2.6 and Fig. 2.10), where the vertical bonds are the “physical” indexes and the bonds shared by two adjacent tensors are the geometrical indexes. This MPO is also called the transfer operator or transfer MPO of the TN. The converged MPS is in fact the dominant eigenstate of the MPO.2 While the MPO represents a physical Hamiltonian or the imaginary-time evolution operator (see Sect. 3.1), the MPS is the ground state. For more general situations, e.g., the TN represents a 2D partition function or the inner product of two 2D PEPSs, the MPS can be understood as the boundary state of the TN (or the PEPS ) [48–50]. The contraction of the 2D infinite TN becomes computing the boundary state, i.e., the dominant eigenstate (and eigenvalue) of the transfer MPO.

The boundary-state scheme gives several non-trivial physical and algorithmic implications [48–52], including the underlying resemblance between iTEBD and the famous infinite DMRG (iDMRG) [53]. DMRG [54, 55] follows the idea of Wilson’s NRG [56], and solves the ground states and low-lying excitations of 1D or quasi-1D Hamiltonians (see several reviews [57–60]); originally it has no direct relations to TN contraction problems. After the MPS and MPO become well understood, DMRG was re-interpreted in a manner that is more close to TN (see a review by Schollwöck [57]). In particular for simulating the ground states of infinite-size 1D systems, the underlying connections between the iDMRG and iTEBD were discussed by McCulloch [53]. As argued above, the contraction of a TN can be computed by solving the dominant eigenstate of its transfer MPO. The eigenstates reached by iDMRG and iTEBD are the same state up to a gauge transformation (note the gauge degrees of freedom of MPS will be discussed in Sect. 2.4.2). Considering that DMRG mostly is not used to compute TN contractions and there are already several understanding reviews, we skip the technical details of the DMRG algorithms here. One may refer to the papers mentioned above if interested. However, later we will revisit iDMRG in the clue of multi-linear algebra.

Variational matrix product state (VMPS)

method is a variational version of DMRG

for (but not limited to) calculating the ground states of 1D systems with periodic boundary condition [61]. Compared with DMRG, VMPS is more directly related to TN

contraction problems. In the following, we explain VMPS by solving the contraction of the infinite square TN. As discussed above, it is equivalent to solve the dominant eigenvector (denoted by |ψ〉) of the infinite MPO

(denoted by  ) that is formed by a row of tensors in the TN. The task is to minimize

) that is formed by a row of tensors in the TN. The task is to minimize  under the constraint 〈ψ|ψ〉 = 1. The eigenstate |ψ〉 written in the form of an MPS

.

under the constraint 〈ψ|ψ〉 = 1. The eigenstate |ψ〉 written in the form of an MPS

.

with

with  the eigenvalue.

the eigenvalue.  is given by a sixth-th order tensor defined by contracting all tensors in

is given by a sixth-th order tensor defined by contracting all tensors in  except for the n-th tensor and its conjugate (Fig. 3.6a). Similarly,

except for the n-th tensor and its conjugate (Fig. 3.6a). Similarly,  is also given by a sixth-th order tensor defined by contracting all tensors in 〈ψ|ψ〉 except for the n-th tensor and its conjugate (Fig. 3.6b). Again, the VMPS is different from the MPS obtained by TEBD

only up to a gauge transformation.

is also given by a sixth-th order tensor defined by contracting all tensors in 〈ψ|ψ〉 except for the n-th tensor and its conjugate (Fig. 3.6b). Again, the VMPS is different from the MPS obtained by TEBD

only up to a gauge transformation.

The illustration of (a)  and (b)

and (b)  in the variational matrix product state method

in the variational matrix product state method

Note that the boundary-state methods are not limited to solving TN contractions. An example is the time-dependent variational principle (TDVP) . The basic idea of TDVP was proposed by Dirac in 1930 [62], and then it was cooperated with the formulation of Hamiltonian [63] and action function [64]. For more details, one could refer to a review by Langhoff et al. [65]. In 2011, TDVP was developed to simulate the time evolution of many-body systems with the help of MPS [66]. Since TDVP (and some other algorithms) concerns directly a quantum Hamiltonian instead of the TN contraction, we skip giving more details of these methods in this paper.

3.5 Transverse Contraction and Folding Trick

For the boundary-state methods introduced above, the boundary states are defined in the real space. Taking iTEBD for the real-time evolution as an example, the contraction is implemented along the time direction, which is to do the time evolution in an explicit way. It is quite natural to consider implementing the contraction along the other direction. In the following, we will introduce the transverse contraction and the folding trick proposed and investigated in Refs. [67–69]. The motivation of transverse contraction is to avoid the explicit simulation of the time-dependent state |ψ(t)〉 that might be difficult to capture due to the fast growth of its entanglement.

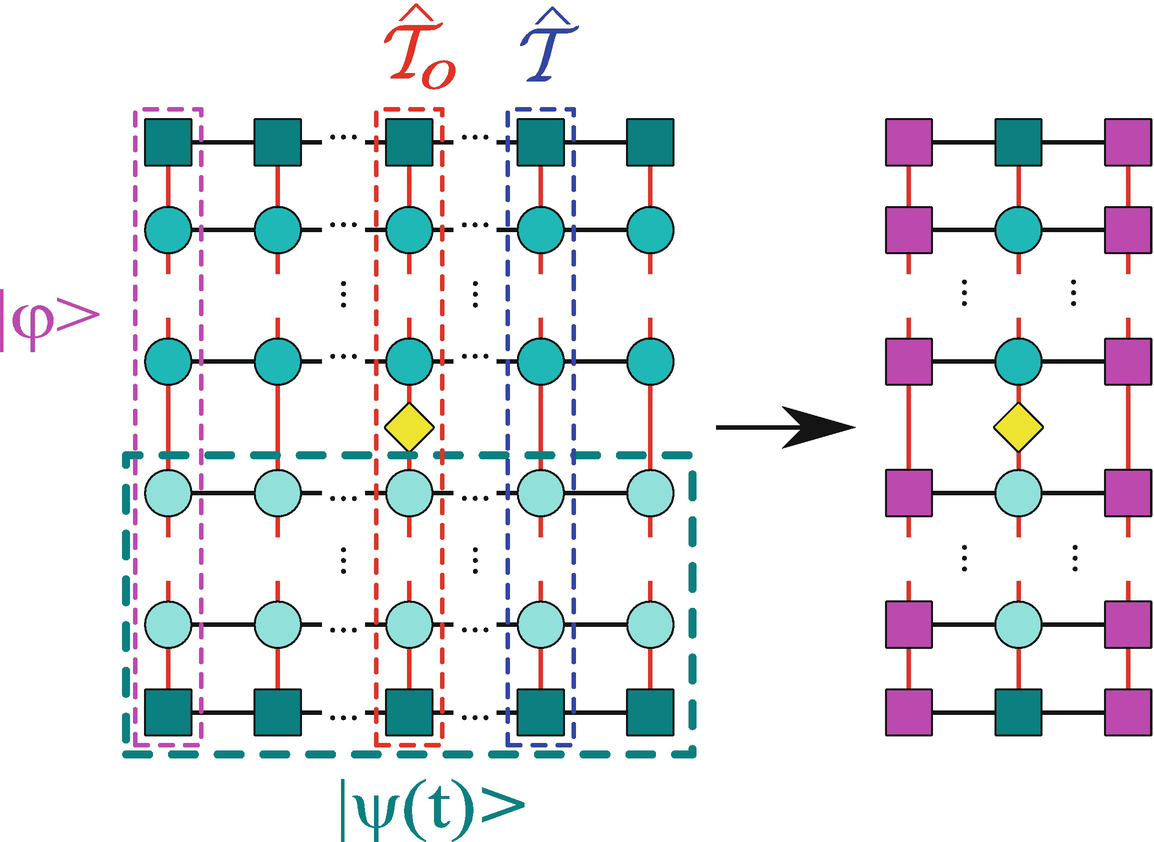

with |ψ(t)〉 that is a quantum state of infinite size evolved to the time t. The TN

representing o(t) is given in the left part of Fig. 3.7, where the green squares give the initial MPS |ψ(0)〉 and its conjugate, the yellow diamond is

with |ψ(t)〉 that is a quantum state of infinite size evolved to the time t. The TN

representing o(t) is given in the left part of Fig. 3.7, where the green squares give the initial MPS |ψ(0)〉 and its conjugate, the yellow diamond is  , and the TN formed by the green circles represents the evolution operator

, and the TN formed by the green circles represents the evolution operator  and its conjugate (see how to define the TN in Sect. 3.1.3).

and its conjugate (see how to define the TN in Sect. 3.1.3).

Transverse contraction of the TN for a local expectation value 〈O(t)〉

. Then as shown in the right part of Fig. 3.7, the main task of computing o(t) is to solve the dominant eigenstate |ϕ〉 (normalized) of

. Then as shown in the right part of Fig. 3.7, the main task of computing o(t) is to solve the dominant eigenstate |ϕ〉 (normalized) of  , which is an MPS

illustrated by the purple squares. One may solve this eigenstate problems by any of the boundary-state methods (TEBD

, DMRG

, etc.). With |ϕ〉, o(t) can be exactly and efficiently calculated as

, which is an MPS

illustrated by the purple squares. One may solve this eigenstate problems by any of the boundary-state methods (TEBD

, DMRG

, etc.). With |ϕ〉, o(t) can be exactly and efficiently calculated as

is the column that contains the operator

is the column that contains the operator  . Note that the length of |ϕ〉 (i.e., the number of tensors in the MPS

) is proportional to the time t, thus one should use the finite-size versions of the boundary-state methods. It should also be noted that

. Note that the length of |ϕ〉 (i.e., the number of tensors in the MPS

) is proportional to the time t, thus one should use the finite-size versions of the boundary-state methods. It should also be noted that  may not be Hermitian. In this case, one should not use |ϕ〉 and its conjugate, but compute the left and right eigenstates of

may not be Hermitian. In this case, one should not use |ϕ〉 and its conjugate, but compute the left and right eigenstates of  instead.

instead.Interestingly, similar ideas of the transverse contraction appeared long before the concept of TN emerged. For instance, transfer matrix renormalization group (TMRG)

[70–73] can be used to simulate the finite-temperature properties of a 1D system. The idea of TMRG is to utilize DMRG

to calculate the dominant eigenstate of the transfer matrix (similar to  ). In correspondence with the TN

terminology, it is to use DMRG to compute |ϕ〉 from the TN that defines the imaginary-time evolution. We will skip of the details of TMRG since it is not directly related to TN. One may refer the related references if interested.

). In correspondence with the TN

terminology, it is to use DMRG to compute |ϕ〉 from the TN that defines the imaginary-time evolution. We will skip of the details of TMRG since it is not directly related to TN. One may refer the related references if interested.

The main bottleneck of a boundary-state method concerns the entanglement of the boundary state. In other words, the methods will become inefficient when the entanglement of the boundary state grows too large. One example is the real-time simulation of a 1D chain, where the entanglement entropy increases linearly with time. Solely with the transverse contraction, it will not essentially solve this problem. Taking the imaginary-time evolution as an example, it has been shown that with the dual symmetry of space and time, the boundary states in the space and time directions possess the same entanglement [69, 74].

The illustration of the folding trick

The previous work [67] on the dynamic simulations of 1D spin chains showed that the entanglement of the boundary state is in fact reduced compared with that of the boundary state without folding. This suggests that the folding trick provides a more efficient representation of the entanglement structure of the boundary state. The authors of Ref. [67] suggested an intuitive picture to understand the folding trick. Consider a product state as the initial state at t − 0 and a single localized excitation at the position x that propagates freely with velocity v. By evolving for a time t, only (x ± vt) sites will become entangled. With the folding trick, the evolutions (that are unitary) besides the (x ± vt) sites will not take effects since they are folded with the conjugates and become identities. Thus the spins outside (x ± vt) will remain product state and will not contribute entanglement to the boundary state. In short, one key factor to consider here is the entanglement structure, i.e., the fact that the TN is formed by unitaries. The transverse contraction with the folding trick is a convincing example to show that the efficiency of contracting a TN can be improved by properly designing the contraction way according to the entanglement structure of the TN.

3.6 Relations to Exactly Contractible Tensor Networks and Entanglement Renormalization

The TN algorithms explained above are aimed at dealing with contracting optimally the TNs that cannot be exactly contracted. Then a question arises: Is a classical computer really able to handle these TNs? In the following, we show that by explicitly putting the isometries for truncations inside, the TNs that are contracted in these algorithms become eventually exactly contractible, dubbed as exactly contractible TN (ECTN) . Different algorithms lead to different ECTN. That means the algorithm will show a high performance if the TN can be accurately approximated by the corresponding ETNC.

The exactly contractible TN in the HOTRG algorithm

The exactly contractible TN in the iTEBD algorithm

A part of the exactly contractible TN in the CTMRG algorithm

For these three algorithms, each of them gives an ECTN that is formed by two part: the tensors in the original TN and the isometries that make the TN exactly contractible. After optimizing the isometries, the original TN is approximated by the ECTN. The structure of the ECTN depends mainly on the contraction strategy and the way of optimizing the isometries depends on the chosen environment.

The ECTN picture shows us explicitly how the correlations and entanglement are approximated in different algorithms. Roughly speaking, the correlation properties can be read from the minimal distance of the path in the ECTN that connects two certain sites, and the (bipartite) entanglement can be read from the number of bonds that cross the boundary of the bipartition. How well the structure suits the correlations and entanglement should be a key factor of the performance of a TN contraction algorithm. Meanwhile, this picture can assist us to develop new algorithms by designing the ECTN and taking the whole ECTN as the environment for optimizing the isometries. These issues still need further investigations.

The unification of the TN contraction and the ECTN has been explicitly utilized in the TN renormalization (TNR) algorithm [77, 78], where both isometries and unitaries (called disentangler) are put into the TN to make it exactly contractible. Then instead of tree TNs or MPSs , one will have MERAs (see Fig. 2.7c, for example) inside which can better capture the entanglement of critical systems.

3.7 A Shot Summary

In this section, we have discussed about several contraction approaches for dealing with 2D TNs. Applying these algorithms, many challenging problems can be efficiently solved, including the ground-state and finite-temperature simulations of 1D quantum systems, and the simulations of 2D classical statistic models. Such algorithms consist of two key ingredients: contractions (local operations of tensors) and truncations. The local contraction determines the way how the TN is contracted step by step, or in other words, how the entanglement information is kept according to the ECTN structure. Different (local or global) contractions may lead to different computational costs, thus optimizing the contraction sequence is necessary in many cases [67, 79, 80]. The truncation is the approximation to discard less important basis so that the computational costs are properly bounded. One essential concept in the truncations is “environment,” which plays the role of the reference when determining the weights of the basis. Thus, the choice of environment concerns the balance between the accuracy and efficiency of a TN algorithm.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.