![]()

Women are far more likely to present with this symptom than men, often for cosmetic reasons. The likeliest queries relate to normal nails that break easily or are not smooth. Other abnormalities may be detected during physical examination rather than being volunteered by the patient, and may indicate significant pathology.

![]()

COMMON

psoriasis

psoriasis

fungal infection: onychomycosis

fungal infection: onychomycosis

trauma to nail bed

trauma to nail bed

trauma due to biting (also hang nail)

trauma due to biting (also hang nail)

onychogryphosis (OG)

onychogryphosis (OG)

OCCASIONAL

trophic changes (Beau’s lines) – appear 2–3 months after severe illness

trophic changes (Beau’s lines) – appear 2–3 months after severe illness

hand eczema

hand eczema

longitudinal ridging (onychorrhexis)

longitudinal ridging (onychorrhexis)

chronic paronychia

chronic paronychia

clubbing (various causes)

clubbing (various causes)

autoimmune disease (e.g. alopecia areata, lichen planus)

autoimmune disease (e.g. alopecia areata, lichen planus)

koilonychia (spoon nails): iron deficiency anaemia and Plummer–Vinson syndrome

koilonychia (spoon nails): iron deficiency anaemia and Plummer–Vinson syndrome

RARE

subungual melanoma

subungual melanoma

leuconychia (e.g. liver disease, diabetes)

leuconychia (e.g. liver disease, diabetes)

lamellar nail dystrophy

lamellar nail dystrophy

yellow nail syndrome (may be accompanied by chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis or pleural effusion)

yellow nail syndrome (may be accompanied by chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis or pleural effusion)

exfoliative dermatitis: nail shedding

exfoliative dermatitis: nail shedding

nail dystrophy due to poor circulation (e.g. Raynaud’s disease)

nail dystrophy due to poor circulation (e.g. Raynaud’s disease)

epidermolysis bullosa

epidermolysis bullosa

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: nail clippings for mycology.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, FBC.

SMALL PRINT: LFT, CXR.

Nail clippings for mycology may be the only way to differentiate psoriatic nail dystrophy and onychomycosis.

Nail clippings for mycology may be the only way to differentiate psoriatic nail dystrophy and onychomycosis.

Urinalysis worthwhile if nails are unusually white: this can occur in diabetes.

Urinalysis worthwhile if nails are unusually white: this can occur in diabetes.

FBC may confirm iron deficiency anaemia in koilonychia.

FBC may confirm iron deficiency anaemia in koilonychia.

LFT: to assess liver function in leuconychia.

LFT: to assess liver function in leuconychia.

CXR worthwhile if chest symptoms with clubbing or yellow nails.

CXR worthwhile if chest symptoms with clubbing or yellow nails.

Don’t confine your examination to the nails – useful clues may be found elsewhere, e.g. patches of psoriasis or coexisting tinea corporis.

The commonest differentials are psoriasis and fungal infections. The latter are usually asymmetrical.

The commonest differentials are psoriasis and fungal infections. The latter are usually asymmetrical.

Patients usually worry about vitamin or calcium deficiencies – these are never the real cause.

Patients usually worry about vitamin or calcium deficiencies – these are never the real cause.

By the time Beau’s lines are obvious to the patient, 3 months or so will have passed from the precipitating event – look back in the records for aetiological clues.

By the time Beau’s lines are obvious to the patient, 3 months or so will have passed from the precipitating event – look back in the records for aetiological clues.

Subungual melanoma is rare and is easily confused with the much more common subungual haematoma. Possible pointers include nail destruction, extension of pigment onto the nail fold and longitudinal bands of pigment. If in doubt, refer.

Subungual melanoma is rare and is easily confused with the much more common subungual haematoma. Possible pointers include nail destruction, extension of pigment onto the nail fold and longitudinal bands of pigment. If in doubt, refer.

Clubbing is really an abnormality of the fingertips; if noted, be alert to signs of major pulmonary or cardiac disease. Carcinoma of the lung is the commonest cause.

Clubbing is really an abnormality of the fingertips; if noted, be alert to signs of major pulmonary or cardiac disease. Carcinoma of the lung is the commonest cause.

Don’t assume crumbly white nails are caused by fungus. Before embarking on lengthy antifungal treatment, try to confirm the diagnosis with nail clippings.

Don’t assume crumbly white nails are caused by fungus. Before embarking on lengthy antifungal treatment, try to confirm the diagnosis with nail clippings.

Severely bitten nails may be a minor symptom of a major anxiety disorder. Be aware of the possible need to explore psychological issues.

Severely bitten nails may be a minor symptom of a major anxiety disorder. Be aware of the possible need to explore psychological issues.

![]()

This is defined as excess growth of terminal hair in women in male distribution sites (i.e. chin, cheeks, upper lip, lower abdomen and thighs). It presents as a cosmetic problem. Ethnic origin must be taken into account: Mediterraneans and Indians grow more than Nordics. Japanese, Chinese and American Indians grow the least. In the UK, according to surveys, up to 15% of women believe they have excess body hair, although only a minority present to the GP.

![]()

COMMON

constitutional (physiological)

constitutional (physiological)

polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): 50% of cases

polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): 50% of cases

anorexia nervosa

anorexia nervosa

menopause

menopause

iatrogenic, e.g. phenytoin, minoxidil, danazol, glucocorticoids

iatrogenic, e.g. phenytoin, minoxidil, danazol, glucocorticoids

OCCASIONAL

congenital adrenal hyperplasia (1 in 5000)

congenital adrenal hyperplasia (1 in 5000)

anabolic steroid abuse

anabolic steroid abuse

ovarian tumours: arrhenoblastoma, hilus cell tumour, luteoma

ovarian tumours: arrhenoblastoma, hilus cell tumour, luteoma

adrenal tumours: carcinoma and adenoma

adrenal tumours: carcinoma and adenoma

congenital (1 in 5000 live births) and juvenile hypothyroidism

congenital (1 in 5000 live births) and juvenile hypothyroidism

RARE

acromegaly (incidence 3 per million)

acromegaly (incidence 3 per million)

porphyria cutanea tarda

porphyria cutanea tarda

Cushing’s syndrome (incidence 1–2 per million)

Cushing’s syndrome (incidence 1–2 per million)

hypertrichosis lanuginosa

hypertrichosis lanuginosa

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (Amsterdam dwarfism)

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (Amsterdam dwarfism)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: serum testosterone, pelvic ultrasound, FBC, U&E, TFT.

SMALL PRINT: FSH/LH, other tests of endocrine function and specialised imaging techniques (for adrenal/pituitary disorders), urinary porphyrins.

Serum testosterone: probably the most useful investigation. Mild elevation (up to three times the normal value) suggests PCOS; levels above this indicate a possible tumour.

Serum testosterone: probably the most useful investigation. Mild elevation (up to three times the normal value) suggests PCOS; levels above this indicate a possible tumour.

FBC, U&E: possible iron deficiency anaemia and electrolyte disturbance in anorexia; U&E may be deranged in adrenal disorders.

FBC, U&E: possible iron deficiency anaemia and electrolyte disturbance in anorexia; U&E may be deranged in adrenal disorders.

FSH/LH and TFT: the former may help to confirm menopause and may point towards PCOS (elevated LH, normal FSH); the latter reveals hypothyroidism.

FSH/LH and TFT: the former may help to confirm menopause and may point towards PCOS (elevated LH, normal FSH); the latter reveals hypothyroidism.

Other tests of endocrine function and imaging techniques: to investigate possible adrenal and pituitary disorders (usually undertaken in secondary care).

Other tests of endocrine function and imaging techniques: to investigate possible adrenal and pituitary disorders (usually undertaken in secondary care).

Pelvic ultrasound: multiple ovarian cysts characteristic of PCOS; may also reveal ovarian tumour.

Pelvic ultrasound: multiple ovarian cysts characteristic of PCOS; may also reveal ovarian tumour.

Urinary porphyrins: for porphyria.

Urinary porphyrins: for porphyria.

Mild, long-standing hirsutism does not require investigation.

Mild, long-standing hirsutism does not require investigation.

Enquire about self-medication, especially in athletes – anabolic steroids may occasionally be the cause.

Enquire about self-medication, especially in athletes – anabolic steroids may occasionally be the cause.

Take the problem seriously and be prepared for questions about cosmetic treatments such as bleaching, depilatory creams and electrolysis.

Take the problem seriously and be prepared for questions about cosmetic treatments such as bleaching, depilatory creams and electrolysis.

Sudden and severe hirsutism is the most important marker for serious underlying pathology.

Sudden and severe hirsutism is the most important marker for serious underlying pathology.

Other clues suggesting a possible hormone-secreting tumour include amenorrhoea, onset of baldness at the same time as hirsutism and a patient who seems generally unwell.

Other clues suggesting a possible hormone-secreting tumour include amenorrhoea, onset of baldness at the same time as hirsutism and a patient who seems generally unwell.

Consider psychological factors: hirsutism can cause – or be the presenting complaint in – significant depression.

Consider psychological factors: hirsutism can cause – or be the presenting complaint in – significant depression.

Recent onset of significant headache and visual field defect raise the possibility of a pituitary adenoma.

Recent onset of significant headache and visual field defect raise the possibility of a pituitary adenoma.

![]()

A distressing symptom for both genders: men fear loss of potency, and women are horrified at the cosmetic disaster unfolding. The psychological significance of increased hairfall is all too easy to overlook in a typical busy surgery. Take care to acknowledge that the problem is being taken seriously.

![]()

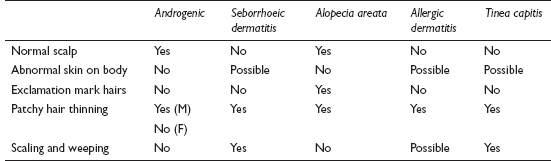

COMMON

androgenic alopecia (male pattern baldness)

androgenic alopecia (male pattern baldness)

seborrhoeic dermatitis

seborrhoeic dermatitis

alopecia areata

alopecia areata

contact allergic dermatitis

contact allergic dermatitis

tinea capitis

tinea capitis

OCCASIONAL

bacterial folliculitis

bacterial folliculitis

telogen effluvium

telogen effluvium

endocrine: myxoedema, hypopituitarism and hypoparathyroidism

endocrine: myxoedema, hypopituitarism and hypoparathyroidism

traction alopecia

traction alopecia

lupus erythematosus

lupus erythematosus

RARE

secondary syphilis

secondary syphilis

trichotillomania

trichotillomania

morphoea

morphoea

iatrogenic, e.g. chemotherapy, anticoagulants

iatrogenic, e.g. chemotherapy, anticoagulants

malnutrition

malnutrition

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: Wood’s light test, hair and scales for mycology.

SMALL PRINT: FBC, ESR/CRP, U&E, TFT, FSH/LH, prolactin, autoimmune tests, syphilis serology.

Microsporum infections will fluoresce green under a Wood’s (UV) light.

Microsporum infections will fluoresce green under a Wood’s (UV) light.

Send scrapings and hair for mycology if the scalp looks abnormal.

Send scrapings and hair for mycology if the scalp looks abnormal.

FBC, ESR/CRP and autoimmune tests may help identify autoimmune causes, e.g. SLE.

FBC, ESR/CRP and autoimmune tests may help identify autoimmune causes, e.g. SLE.

Syphilis serology: old-fashioned, but syphilis is on the increase.

Syphilis serology: old-fashioned, but syphilis is on the increase.

U&E, TFT, FSH/LH/prolactin will effectively screen for endocrinopathy.

U&E, TFT, FSH/LH/prolactin will effectively screen for endocrinopathy.

Alopecia areata is occasionally associated with other autoimmune diseases. Further assessment is sensible, even at a later consultation.

Alopecia areata is occasionally associated with other autoimmune diseases. Further assessment is sensible, even at a later consultation.

Remember that in telogen effluvium, the traumatic event – such as a significant illness or childbirth – will have taken place about 4 months before the onset of hair loss, so the connection is unlikely to be made by the patient.

Remember that in telogen effluvium, the traumatic event – such as a significant illness or childbirth – will have taken place about 4 months before the onset of hair loss, so the connection is unlikely to be made by the patient.

The patient invariably fears total hair loss – ensure that this is broached and that a realistic prognosis is given.

The patient invariably fears total hair loss – ensure that this is broached and that a realistic prognosis is given.

Reassure men with male-pattern baldness who are anxious about their potency. In this case it signifies the opposite. Its onset is related to adequate circulating testosterone. Eunuchs tend not to go bald.

Reassure men with male-pattern baldness who are anxious about their potency. In this case it signifies the opposite. Its onset is related to adequate circulating testosterone. Eunuchs tend not to go bald.

Lymphadenopathy in association with alopecia may suggest an infective process: consider bacterial folliculitis.

Lymphadenopathy in association with alopecia may suggest an infective process: consider bacterial folliculitis.

Alopecia areata has a particularly poor prognosis if there are several patches, there is loss of eyebrows or eyelashes, or if it begins in childhood.

Alopecia areata has a particularly poor prognosis if there are several patches, there is loss of eyebrows or eyelashes, or if it begins in childhood.

Scarring alopecia should prompt the clinician to look for general signs of lupus erythematosus.

Scarring alopecia should prompt the clinician to look for general signs of lupus erythematosus.

Trichotillomania in children is usually simply due to habit; in adults, though, it is more often a sign of significant psychological disturbance.

Trichotillomania in children is usually simply due to habit; in adults, though, it is more often a sign of significant psychological disturbance.

![]()

This might appear a mundane symptom to the GP, but it can cause the patient significant distress. It’s usually a welcome presentation, as it’s perceived as a quickie – one of those problems in which a brief examination can be performed at the same time as an equally brief history. This approach generally pays dividends, but the problem can sometimes be more complicated than it might at first appear.

![]()

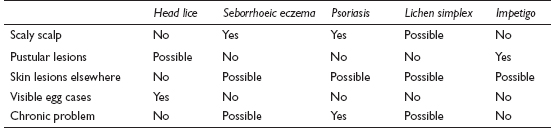

COMMON

head lice

head lice

seborrhoeic eczema

seborrhoeic eczema

psoriasis

psoriasis

lichen simplex

lichen simplex

impetigo (may be underlying head lice or eczema)

impetigo (may be underlying head lice or eczema)

OCCASIONAL

allergic/contact eczema

allergic/contact eczema

other fungal infections

other fungal infections

RARE

stress/depression

stress/depression

viral infection, e.g. chickenpox – a common problem but only rarely presents with scalp itch

viral infection, e.g. chickenpox – a common problem but only rarely presents with scalp itch

![]()

![]()

It is highly unlikely that any investigations will be required at all. Confirmation of a fungal infection may be obtained via fluorescence under a Wood’s light or by microscopy and culture of scalp and hair samples.

Whatever the actual diagnosis, scratching will perpetuate or complicate the problem and so should be discouraged.

Whatever the actual diagnosis, scratching will perpetuate or complicate the problem and so should be discouraged.

Consider examining the skin and nails, as these may provide useful additional clues.

Consider examining the skin and nails, as these may provide useful additional clues.

The diagnosis in a child is very likely to be head lice; the list of differentials increases the older the patient.

The diagnosis in a child is very likely to be head lice; the list of differentials increases the older the patient.

Scalp impetigo in a child – particularly if it relapses rapidly – suggests an underlying problem such as head lice or eczema. This needs treating too, or the symptom will persist.

Scalp impetigo in a child – particularly if it relapses rapidly – suggests an underlying problem such as head lice or eczema. This needs treating too, or the symptom will persist.

In an otherwise puzzling case, consider psychological causes – stress and depression can sometimes present with scalp itching.

In an otherwise puzzling case, consider psychological causes – stress and depression can sometimes present with scalp itching.