![]()

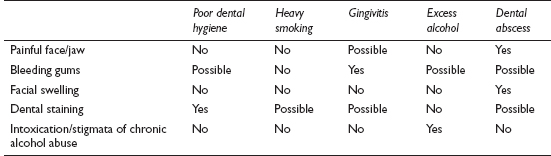

This common symptom is usually caused by poor dental hygiene. As a presenting complaint it is seen far more often by dentists than GPs. It may be detected by a doctor examining a patient for an unrelated complaint, and rarely but significantly can herald serious pathology.

![]()

COMMON

poor dental hygiene

poor dental hygiene

heavy smoking

heavy smoking

gingivitis (including acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), acute and chronic gingivitis)

gingivitis (including acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), acute and chronic gingivitis)

excess alcohol intake (acute and chronic)

excess alcohol intake (acute and chronic)

discharging dental abscess

discharging dental abscess

OCCASIONAL

ketohalitosis of starvation – especially in people using high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate weight reduction diet regimens (and pre-operatively starved patients)

ketohalitosis of starvation – especially in people using high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate weight reduction diet regimens (and pre-operatively starved patients)

drugs, e.g. disulfiram

drugs, e.g. disulfiram

acute or chronic sinusitis

acute or chronic sinusitis

subjectively perceived (non-existent) halitosis (sometimes a form of somatisation)

subjectively perceived (non-existent) halitosis (sometimes a form of somatisation)

GORD or acute gastroenteritis with reflux of gas

GORD or acute gastroenteritis with reflux of gas

RARE

bronchiectasis

bronchiectasis

liver failure – hepatic foetor is said to smell like a freshly opened corpse; this is due to mercaptans in expired air

liver failure – hepatic foetor is said to smell like a freshly opened corpse; this is due to mercaptans in expired air

true delusional subjective halitosis as part of psychiatric condition, e.g. severe depression with nihilism, psychotic illnesses

true delusional subjective halitosis as part of psychiatric condition, e.g. severe depression with nihilism, psychotic illnesses

rare oral or nasal conditions, e.g. pyogenic granuloma, discharging sinus from abscess

rare oral or nasal conditions, e.g. pyogenic granuloma, discharging sinus from abscess

![]()

![]()

It is unlikely that the GP will initiate any investigations other than LFT if alcohol is a likely aetiology, or liver failure is suspected. CXR may be helpful if bronchiectasis is a possibility. Dentists may carry out the following investigations.

Plaque and bleeding indexes – for oral hygiene.

Plaque and bleeding indexes – for oral hygiene.

Basic periodontal examination – measurement of pocket depth between gums and teeth carried out with a specially marked probe.

Basic periodontal examination – measurement of pocket depth between gums and teeth carried out with a specially marked probe.

Oral pantomograph X-ray to investigate general state of teeth.

Oral pantomograph X-ray to investigate general state of teeth.

If a dental cause is suspected, rather than telling the patient to make their own appointment with a dentist, give a short referral letter for them to hand over. This will ensure and record that you have carried out proper management and may speed things considerably for the patient.

If a dental cause is suspected, rather than telling the patient to make their own appointment with a dentist, give a short referral letter for them to hand over. This will ensure and record that you have carried out proper management and may speed things considerably for the patient.

The vast majority of cases will involve oral hygiene. Be certain to exclude this, and other physical causes, before deciding that the halitosis is entirely subjective. As with other forms of somatisation, active management – with a psychiatric referral if necessary – is preferable to sending the patient away, only to return to make more appointments.

The vast majority of cases will involve oral hygiene. Be certain to exclude this, and other physical causes, before deciding that the halitosis is entirely subjective. As with other forms of somatisation, active management – with a psychiatric referral if necessary – is preferable to sending the patient away, only to return to make more appointments.

If no obvious oral cause is found initially, extend the history and examination to include the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems.

If no obvious oral cause is found initially, extend the history and examination to include the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems.

ANUG is a ‘spot diagnosis’ – the stench usually precedes the patient by some distance.

ANUG is a ‘spot diagnosis’ – the stench usually precedes the patient by some distance.

In the absence of an obvious cause, do not neglect to examine the head and neck including the buccal cavity and nasal airway. Failure to do so could mean that a serious local cause is missed.

In the absence of an obvious cause, do not neglect to examine the head and neck including the buccal cavity and nasal airway. Failure to do so could mean that a serious local cause is missed.

Do not overlook alcohol abuse as a possible underlying cause.

Do not overlook alcohol abuse as a possible underlying cause.

If the impact of the symptom seems out of all proportion to any objective sign of a problem, consider depression.

If the impact of the symptom seems out of all proportion to any objective sign of a problem, consider depression.

![]()

The primary cause of this symptom is nearly always infection, usually because of poor dental hygiene: an endemic problem worldwide. Systemic problems may also cause gum pain or bleeding. While a dental referral is likely to be the end result, it is worth checking for general causes or easily remediable problems before directing the patient to the dentist.

![]()

COMMON

gingivitis/periodontal (gum) disease

gingivitis/periodontal (gum) disease

pregnancy gingivitis

pregnancy gingivitis

acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG): Vincent’s stomatitis

acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG): Vincent’s stomatitis

trauma: poorly fitting dentures

trauma: poorly fitting dentures

drugs: warfarin overdosage, long-term phenytoin

drugs: warfarin overdosage, long-term phenytoin

OCCASIONAL

aphthous ulceration

aphthous ulceration

acute herpetic gingivostomatitis (occasionally EBV)

acute herpetic gingivostomatitis (occasionally EBV)

autoimmune disease: lichen planus, SLE and others

autoimmune disease: lichen planus, SLE and others

oral neoplasia (commonest is SCC) (Note: may bleed but usually painless)

oral neoplasia (commonest is SCC) (Note: may bleed but usually painless)

blood dyscrasias (especially acute myeloid leukaemia)

blood dyscrasias (especially acute myeloid leukaemia)

RARE

malabsorption (including scurvy)

malabsorption (including scurvy)

chemical poisoning: mercury, phosphorus, arsenic and lead

chemical poisoning: mercury, phosphorus, arsenic and lead

hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

lymphangioma

lymphangioma

cavernous haemangioma

cavernous haemangioma

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: FBC.

SMALL PRINT: swab, INR, autoimmune screen, Paul–Bunnell test.

FBC: to check for blood dyscrasias and malabsorption.

FBC: to check for blood dyscrasias and malabsorption.

Swab may help if obscure infective cause.

Swab may help if obscure infective cause.

Urgent INR if patient on warfarin.

Urgent INR if patient on warfarin.

Paul–Bunnell test: EBV infection may cause gingivostomatitis.

Paul–Bunnell test: EBV infection may cause gingivostomatitis.

Autoimmune screen if autoimmune disease suspected.

Autoimmune screen if autoimmune disease suspected.

Patients with manifestly ‘dental’ problems may attend the GP because they view the doctor’s service as cheaper or more accessible. Direct them firmly to the dentist to discourage inappropriate attendance in the future.

Patients with manifestly ‘dental’ problems may attend the GP because they view the doctor’s service as cheaper or more accessible. Direct them firmly to the dentist to discourage inappropriate attendance in the future.

Review the patient’s medication – it is easy to overlook iatrogenic causes of gum soreness or bleeding.

Review the patient’s medication – it is easy to overlook iatrogenic causes of gum soreness or bleeding.

Patients with aphthous ulcers are likely to have read that their problem is associated with vitamin deficiencies or systemic illness. In primary care, it almost never is.

Patients with aphthous ulcers are likely to have read that their problem is associated with vitamin deficiencies or systemic illness. In primary care, it almost never is.

Ulcerative gingivitis can often be diagnosed as soon as the patient walks into the consulting room, because of the characteristic odour.

Ulcerative gingivitis can often be diagnosed as soon as the patient walks into the consulting room, because of the characteristic odour.

Children with primary attacks of herpetic gingivostomatitis can become quite ill and dehydrated. Consider early review or admission.

Children with primary attacks of herpetic gingivostomatitis can become quite ill and dehydrated. Consider early review or admission.

Petechiae on the soft palate in conjunction with gingivostomatitis raise the possibility of EBV infection, acute leukaemia or scurvy.

Petechiae on the soft palate in conjunction with gingivostomatitis raise the possibility of EBV infection, acute leukaemia or scurvy.

Enquire about skin problems elsewhere, or you may miss a significant diagnosis: SLE, pemphigus, pemphigoid, bullous erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa and lichen planus can all affect the mouth.

Enquire about skin problems elsewhere, or you may miss a significant diagnosis: SLE, pemphigus, pemphigoid, bullous erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa and lichen planus can all affect the mouth.

![]()

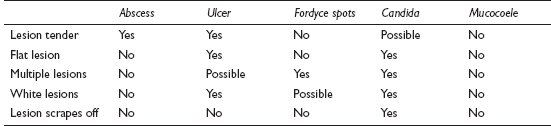

Mouth lumps and marks can be unfamiliar territory – partly because it is rarely an area of expertise for many GPs, and partly because many mouth problems are picked up by, or presented to, dentists in the first place. A proportion of patients will choose a GP as the first port of call, so a working knowledge of the area is useful.

![]()

COMMON

apical tooth abscess (gumboil)

apical tooth abscess (gumboil)

aphthous ulceration

aphthous ulceration

Fordyce spots (tiny white or yellow spots, on mucosa opposite molars and vermilion border of lips; they are sebaceous glands)

Fordyce spots (tiny white or yellow spots, on mucosa opposite molars and vermilion border of lips; they are sebaceous glands)

oral candida infection

oral candida infection

mucocoele (solitary cystic nodule inside lip)

mucocoele (solitary cystic nodule inside lip)

OCCASIONAL

lichen planus

lichen planus

trauma – bitten cheek

trauma – bitten cheek

ranula

ranula

torus – benign maxillary or mandibular outgrowth of bone (very common but usually asymptomatic so not commonly seen)

torus – benign maxillary or mandibular outgrowth of bone (very common but usually asymptomatic so not commonly seen)

premalignant coloured areas: erythroplakia (red), leukoplakia (white), speckled leukoplakia

premalignant coloured areas: erythroplakia (red), leukoplakia (white), speckled leukoplakia

(red and white), or verrucous leukoplakia

geographical and hairy tongue

geographical and hairy tongue

tonsillar concretions

tonsillar concretions

other forms of oral ulceration (see Mouth ulcers, p. 356)

other forms of oral ulceration (see Mouth ulcers, p. 356)

RARE

malignancy – SCC or melanoma

malignancy – SCC or melanoma

pachyderma oralis (from irritants)

pachyderma oralis (from irritants)

heavy metal poisoning (lead, bismuth, iron) – a dark line below the gingival margin

heavy metal poisoning (lead, bismuth, iron) – a dark line below the gingival margin

cancrum oris

cancrum oris

sublingual gland tumour

sublingual gland tumour

pigmentation due to oral contraceptive pill – black or brown areas anywhere in the mouth

pigmentation due to oral contraceptive pill – black or brown areas anywhere in the mouth

Addison’s disease – bluish hue opposite molars

Addison’s disease – bluish hue opposite molars

Peutz–Jeghers spots – brown spots on the lips

Peutz–Jeghers spots – brown spots on the lips

telangiectasia – may be a sign of Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome

telangiectasia – may be a sign of Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome

Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Stevens–Johnson syndrome

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

OCCASIONAL: FBC, ESR, CRP, ferritin, B12 and folate, fasting glucose or HbA1c, swab of lesion, HIV test.

SMALL PRINT: biopsy (performed at hospital).

FBC, ESR, CRP and HIV are useful if immune deficiency (e.g. as a background to Candida infection) is suspected; FBC and ESR or CRP may be helpful in suspected malignancy too.

FBC, ESR, CRP and HIV are useful if immune deficiency (e.g. as a background to Candida infection) is suspected; FBC and ESR or CRP may be helpful in suspected malignancy too.

Ferritin, B12 and folate deficiency is sometimes associated with oral aphthous ulceration – worth checking these in cases of recurrent or chronic ulceration (and see other possible investigations in Mouth ulcers, p. 356).

Ferritin, B12 and folate deficiency is sometimes associated with oral aphthous ulceration – worth checking these in cases of recurrent or chronic ulceration (and see other possible investigations in Mouth ulcers, p. 356).

Fasting glucose or HbA1c to investigate possible diabetes if candidal infection otherwise unexplained.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c to investigate possible diabetes if candidal infection otherwise unexplained.

Mouth swab to confirm candidal infection, though a diagnostic trial of treatment is often the practical first step.

Mouth swab to confirm candidal infection, though a diagnostic trial of treatment is often the practical first step.

Biopsy: of suspicious lesions – this is inevitably performed in secondary care.

Biopsy: of suspicious lesions – this is inevitably performed in secondary care.

Recurrent oral aphthous ulceration is a feature of a few systemic diseases (e.g. coeliac disease, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s disease and AIDS) so be prepared to re-evaluate the history and widen the net of information gathering in repeat presentations.

Recurrent oral aphthous ulceration is a feature of a few systemic diseases (e.g. coeliac disease, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s disease and AIDS) so be prepared to re-evaluate the history and widen the net of information gathering in repeat presentations.

It is tempting to give antibiotics for a dental abscess, but the old surgical maxim ‘if there’s pus about, let it out’ still holds true. Antibiotics may help reduce pain and surrounding infection but are only a temporary measure and may delay definitive treatment in those trying to avoid seeing a dentist, and increase the risk of complications. Encourage patients to see a dentist in the first place: offering a referral letter is helpful and may help to overcome any possible barrier to urgent access to a dentist at the dental reception desk.

It is tempting to give antibiotics for a dental abscess, but the old surgical maxim ‘if there’s pus about, let it out’ still holds true. Antibiotics may help reduce pain and surrounding infection but are only a temporary measure and may delay definitive treatment in those trying to avoid seeing a dentist, and increase the risk of complications. Encourage patients to see a dentist in the first place: offering a referral letter is helpful and may help to overcome any possible barrier to urgent access to a dentist at the dental reception desk.

Always examine lumps by palpation from inside as well as outside the mouth. Wash latex gloves before the examination. Glove powder tastes foul!

Always examine lumps by palpation from inside as well as outside the mouth. Wash latex gloves before the examination. Glove powder tastes foul!

Always refer the patient with permanent red or white buccal mucosal patches. Biopsy is indicated.

Always refer the patient with permanent red or white buccal mucosal patches. Biopsy is indicated.

If an ulcer fails to heal within a few weeks, especially if it is painless, refer for a specialist opinion as a suspected malignancy.

If an ulcer fails to heal within a few weeks, especially if it is painless, refer for a specialist opinion as a suspected malignancy.

Do not fail to examine regional lymph nodes. Enlarged nodes would be a significant finding, especially if they are non-tender and persistent.

Do not fail to examine regional lymph nodes. Enlarged nodes would be a significant finding, especially if they are non-tender and persistent.

![]()

This symptom may often make a GP feel baffled – largely because it tends to be overlooked, or dealt with only briefly, during medical training. In fact common causes are simple to detect and treat, and it is clearly important to detect the occasional serious problem at an early stage. Examination could hardly be simpler, and a dentist may well have a clearer idea if referral is necessary in more obscure cases.

![]()

COMMON

trauma

trauma

recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU)

recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU)

acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG)

acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG)

thrush

thrush

iron-deficiency anaemia (also vitamin B12 and folate deficiency)

iron-deficiency anaemia (also vitamin B12 and folate deficiency)

OCCASIONAL

Coxsackie virus: herpangina, hand, foot and mouth

Coxsackie virus: herpangina, hand, foot and mouth

inflammatory bowel disease: ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

inflammatory bowel disease: ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

coeliac disease

coeliac disease

herpes simplex and zoster

herpes simplex and zoster

glandular fever (EBV): infectious mononucleosis

glandular fever (EBV): infectious mononucleosis

erosive lichen planus

erosive lichen planus

RARE

carcinoma: squamous cell, salivary gland

carcinoma: squamous cell, salivary gland

autoimmune: Behçet’s syndrome, pemphigoid, pemphigus, bullous erythema multiforme

autoimmune: Behçet’s syndrome, pemphigoid, pemphigus, bullous erythema multiforme

syphilitic chancre or gumma

syphilitic chancre or gumma

leukaemia, agranulocytosis (may be iatrogenic)

leukaemia, agranulocytosis (may be iatrogenic)

tuberculosis

tuberculosis

HIV infection

HIV infection

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: FBC.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, vitamin B12 and folate, coeliac screen.

SMALL PRINT: swab, autoantibody screen, syphilis and HIV serology, biopsy.

FBC: essential basic investigation for anaemia and rarer blood dyscrasias.

FBC: essential basic investigation for anaemia and rarer blood dyscrasias.

Urinalysis: check for glycosuria. Underlying diabetes may predispose to infective causes (especially Candida).

Urinalysis: check for glycosuria. Underlying diabetes may predispose to infective causes (especially Candida).

Vitamin B12 and folate: to establish if underlying vitamin deficiency (especially if MCV raised).

Vitamin B12 and folate: to establish if underlying vitamin deficiency (especially if MCV raised).

Coeliac screen: anti-endomysial and anti-gliadin antibodies suggest coeliac disease if positive.

Coeliac screen: anti-endomysial and anti-gliadin antibodies suggest coeliac disease if positive.

Swab: may help confirm doubtful diagnosis of ANUG – confirms presence of Vincent’s organisms.

Swab: may help confirm doubtful diagnosis of ANUG – confirms presence of Vincent’s organisms.

Autoantibody screens and HLA tests may be useful if autoimmune causes are suspected.

Autoantibody screens and HLA tests may be useful if autoimmune causes are suspected.

Syphilis or HIV serology: if syphilis or HIV are suspected.

Syphilis or HIV serology: if syphilis or HIV are suspected.

Biopsy: required in persistent ulcer of uncertain aetiology (secondary care investigation).

Biopsy: required in persistent ulcer of uncertain aetiology (secondary care investigation).

Consider vitamin or iron deficiency, especially if the patient has glossitis and angular cheilitis as well as oral ulceration.

Consider vitamin or iron deficiency, especially if the patient has glossitis and angular cheilitis as well as oral ulceration.

The patient with sore, ulcerated gums and foul halitosis has ANUG; the smell is sometimes apparent as soon as the patient walks in.

The patient with sore, ulcerated gums and foul halitosis has ANUG; the smell is sometimes apparent as soon as the patient walks in.

Patients with RAU often believe they are suffering from a vitamin deficiency; in fact, this is rarely the case, but be sure to broach this with them and consider a blood test as this may reinforce your reassurance.

Patients with RAU often believe they are suffering from a vitamin deficiency; in fact, this is rarely the case, but be sure to broach this with them and consider a blood test as this may reinforce your reassurance.

Enquire about skin problems elsewhere in an obscure case – this may give a clue to the precise diagnosis.

Enquire about skin problems elsewhere in an obscure case – this may give a clue to the precise diagnosis.

Faucial ulceration and petechial haemorrhages of the soft palate and pharynx are likely to be caused by glandular fever.

Faucial ulceration and petechial haemorrhages of the soft palate and pharynx are likely to be caused by glandular fever.

A solitary, persistent and often painless ulcer could be malignant – especially in smokers. Refer urgently to the oral surgeon for biopsy.

A solitary, persistent and often painless ulcer could be malignant – especially in smokers. Refer urgently to the oral surgeon for biopsy.

Ask about bowel function: diarrhoea, abdominal pain and bloodstained stools with mucus suggest associated inflammatory bowel disease.

Ask about bowel function: diarrhoea, abdominal pain and bloodstained stools with mucus suggest associated inflammatory bowel disease.

Don’t forget to enquire about medication: blood dyscrasias are a rare but significant side effect of some treatments (e.g. gold, carbimazole), and oral ulceration may be the first sign.

Don’t forget to enquire about medication: blood dyscrasias are a rare but significant side effect of some treatments (e.g. gold, carbimazole), and oral ulceration may be the first sign.

Oral candidiasis is common in the debilitated and those with dentures, but much less so in the otherwise apparently fit. In the latter cases consider underlying problems such as immunosuppression or diabetes.

Oral candidiasis is common in the debilitated and those with dentures, but much less so in the otherwise apparently fit. In the latter cases consider underlying problems such as immunosuppression or diabetes.

![]()

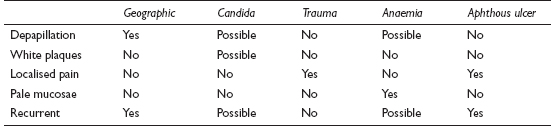

Pain in the tongue is usually caused by something immediately apparent on examination, but there are a few less obvious causes. This is something much more likely to be seen by a dentist, but is not strictly dental and therefore a working knowledge of the symptom is firmly within the GP remit.

![]()

COMMON

geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis) – painful in some cases

geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis) – painful in some cases

candidal infection (e.g. post-antibiotic, steroids and uncontrolled diabetes)

candidal infection (e.g. post-antibiotic, steroids and uncontrolled diabetes)

trauma (bitten, burnt from hot food or drink)

trauma (bitten, burnt from hot food or drink)

anaemia: iron, vitamins B6 and B12, and folate deficiency

anaemia: iron, vitamins B6 and B12, and folate deficiency

aphthous ulceration

aphthous ulceration

OCCASIONAL

viral infection, e.g. herpes simplex, hand, foot and mouth

viral infection, e.g. herpes simplex, hand, foot and mouth

median rhomboid glossitis (superficial midline glossitis)

median rhomboid glossitis (superficial midline glossitis)

burning mouth syndrome (also known as glossodynia)

burning mouth syndrome (also known as glossodynia)

fissured tongue (doesn’t commonly cause pain)

fissured tongue (doesn’t commonly cause pain)

glossopharyngeal neuralgia

glossopharyngeal neuralgia

lichen planus

lichen planus

RARE

carcinoma of the tongue

carcinoma of the tongue

Behçet’s disease

Behçet’s disease

pemphigus vulgaris

pemphigus vulgaris

drugs, e.g. reserpine, mouthwashes, aspirin burns

drugs, e.g. reserpine, mouthwashes, aspirin burns

Moeller’s glossitis

Moeller’s glossitis

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: FBC.

POSSIBLE: vitamin B12, folate and ferritin assays, swab.

SMALL PRINT: biopsy.

FBC initially to screen for anaemia.

FBC initially to screen for anaemia.

Vitamin B12, folate and ferritin assays: if indicated by FBC.

Vitamin B12, folate and ferritin assays: if indicated by FBC.

Swab of tongue may be helpful if appearance not obviously candidal.

Swab of tongue may be helpful if appearance not obviously candidal.

Biopsy of suspicious lesion to determine diagnosis (especially if possible carcinoma or pemphigus).

Biopsy of suspicious lesion to determine diagnosis (especially if possible carcinoma or pemphigus).

Take note of self-medication. Aspirin sucked for toothache can cause a mucosal burn.

Take note of self-medication. Aspirin sucked for toothache can cause a mucosal burn.

A long history of soreness with spicy or bitter foods suggests geographic tongue or median rhomboid glossitis.

A long history of soreness with spicy or bitter foods suggests geographic tongue or median rhomboid glossitis.

A miserable, mildly febrile child with a painful tongue caused by numerous ulcers is likely to have a viral infection such as herpes simplex or hand, foot and mouth disease.

A miserable, mildly febrile child with a painful tongue caused by numerous ulcers is likely to have a viral infection such as herpes simplex or hand, foot and mouth disease.

Check the skin for other lesions in obscure cases – this may reveal the diagnosis (e.g. pemphigus, lichen planus).

Check the skin for other lesions in obscure cases – this may reveal the diagnosis (e.g. pemphigus, lichen planus).

Patients with recurrent aphthous ulcers often erroneously believe they are deficient in vitamins – broach this concern with them.

Patients with recurrent aphthous ulcers often erroneously believe they are deficient in vitamins – broach this concern with them.

If an ulcer in an adult fails to heal within a few weeks of presentation, refer urgently (though most oral neoplastic lesions are initially painless).

If an ulcer in an adult fails to heal within a few weeks of presentation, refer urgently (though most oral neoplastic lesions are initially painless).

The border of geographic tongue changes shape within weeks. This is not the case with more serious pathology.

The border of geographic tongue changes shape within weeks. This is not the case with more serious pathology.

In candidal infections without an obvious cause, consider underlying diabetes or immunosuppression.

In candidal infections without an obvious cause, consider underlying diabetes or immunosuppression.

Glossodynia characteristically produces burning pain on the tip of the tongue: a ‘burner’ is a dentist’s heartsink and the symptom may signify underlying depression.

Glossodynia characteristically produces burning pain on the tip of the tongue: a ‘burner’ is a dentist’s heartsink and the symptom may signify underlying depression.