![]()

This is nearly always seen in women rather than men. In its mildest form it is experienced universally at some time or other associated with periods, ovulation or sexual intercourse. In its severest form it is the commonest reason for urgent laparoscopic examination in the UK.

![]()

COMMON

acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

urinary tract infection (UTI)

urinary tract infection (UTI)

miscarriage

miscarriage

ectopic pregnancy

ectopic pregnancy

ovarian cysts: torsion, rupture

ovarian cysts: torsion, rupture

OCCASIONAL

pelvic abscess (appendix, PID)

pelvic abscess (appendix, PID)

endometriosis

endometriosis

pelvic congestion (exacerbation of pelvic pain syndrome)

pelvic congestion (exacerbation of pelvic pain syndrome)

prostatitis (men)

prostatitis (men)

functional (psychosexual origin)

functional (psychosexual origin)

RARE

misplaced IUCD (perforated uterus)

misplaced IUCD (perforated uterus)

referred (e.g. spinal tumour, bowel spasm)

referred (e.g. spinal tumour, bowel spasm)

proctitis

proctitis

invasive carcinoma of ovaries or cervix

invasive carcinoma of ovaries or cervix

fibroid degeneration

fibroid degeneration

strangulated femoral or inguinal hernia

strangulated femoral or inguinal hernia

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: HVS, cervical swab, urinalysis, MSU.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, pregnancy test, ultrasound, laparoscopy (all usually arranged by hospital admitting team).

SMALL PRINT: none.

Urinalysis: look for nitrites and pus cells to make diagnosis of UTI.

Urinalysis: look for nitrites and pus cells to make diagnosis of UTI.

MSU will confirm UTI and guide antibiotic treatment.

MSU will confirm UTI and guide antibiotic treatment.

HVS for bacteria including gonococcus and endocervical swab for Chlamydia if purulent discharge present.

HVS for bacteria including gonococcus and endocervical swab for Chlamydia if purulent discharge present.

ESR/CRP: elevated in PID.

ESR/CRP: elevated in PID.

Pregnancy test: positive in ectopic and miscarriage.

Pregnancy test: positive in ectopic and miscarriage.

FBC: raised WCC helps confirm PID and UTI if not being admitted. Also elevated in pelvic abscess.

FBC: raised WCC helps confirm PID and UTI if not being admitted. Also elevated in pelvic abscess.

Urgent ultrasound helpful if miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy suspected.

Urgent ultrasound helpful if miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy suspected.

Cases referred to hospital are likely to undergo laparoscopy.

Cases referred to hospital are likely to undergo laparoscopy.

In miscarriage, pain follows bleeding. In ectopic pregnancy, the sequence is usually reversed.

In miscarriage, pain follows bleeding. In ectopic pregnancy, the sequence is usually reversed.

Remember that there may be no bleeding with an ectopic pregnancy – or that the vaginal loss may be a light, blackish discharge.

Remember that there may be no bleeding with an ectopic pregnancy – or that the vaginal loss may be a light, blackish discharge.

PV bleeding will cause haematuria on urinalysis. Only diagnose UTI if the symptoms are suggestive and urinalysis also shows nitrites and pus cells.

PV bleeding will cause haematuria on urinalysis. Only diagnose UTI if the symptoms are suggestive and urinalysis also shows nitrites and pus cells.

Severe unilateral pain and tenderness PV around 6 weeks after last menstrual period (LMP) suggests ectopic pregnancy, even with no bleeding. Admit urgently.

Severe unilateral pain and tenderness PV around 6 weeks after last menstrual period (LMP) suggests ectopic pregnancy, even with no bleeding. Admit urgently.

If PID does not settle within 48 hours of appropriate antibiotic treatment, consider abscess formation.

If PID does not settle within 48 hours of appropriate antibiotic treatment, consider abscess formation.

Don’t forget to check femoral and inguinal canals for a possible strangulated hernia.

Don’t forget to check femoral and inguinal canals for a possible strangulated hernia.

![]()

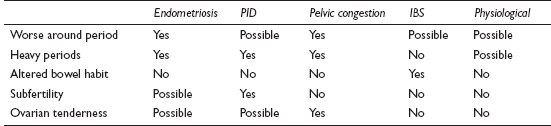

Pelvic pain is defined as chronic if it has been present for three cycles or more. The difference between this and ‘normal’ period pain is one of intensity and duration. It is one of the commonest reasons for referral to a gynaecology clinic and for a woman to see her GP in the first place.

![]()

COMMON

endometriosis

endometriosis

chronic pelvic inflammatory disease

chronic pelvic inflammatory disease

pelvic congestion

pelvic congestion

irritable bowel syndrome

irritable bowel syndrome

physiological (mittelschmerz, primary dysmenorrhoea)

physiological (mittelschmerz, primary dysmenorrhoea)

OCCASIONAL

recurrent UTI

recurrent UTI

musculoskeletal pain (back pain, pubic symphysis pain)

musculoskeletal pain (back pain, pubic symphysis pain)

uterovaginal prolapse

uterovaginal prolapse

benign tumours: ovarian cyst, fibroids

benign tumours: ovarian cyst, fibroids

chronic interstitial cystitis

chronic interstitial cystitis

IUCD

IUCD

adhesions (from previous surgery)

adhesions (from previous surgery)

RARE

malignant tumours (ovary, cervix, bowel)

malignant tumours (ovary, cervix, bowel)

diverticulitis

diverticulitis

lower colonic cancer

lower colonic cancer

inflammatory bowel disease

inflammatory bowel disease

subacute bowel obstruction

subacute bowel obstruction

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: MSU, CA-125.

POSSIBLE: laparoscopy, ultrasound, HVS and cervical swab.

SMALL PRINT: FBC, ESR/CRP, bowel and back imaging.

MSU detects UTI. Red cells alone may be present in interstitial cystitis.

MSU detects UTI. Red cells alone may be present in interstitial cystitis.

CA-125 – especially in women aged 50 or more to help rule out carcinoma of the ovary.

CA-125 – especially in women aged 50 or more to help rule out carcinoma of the ovary.

FBC, ESR/CRP: WCC, ESR/CRP may be raised during exacerbation of chronic PID.

FBC, ESR/CRP: WCC, ESR/CRP may be raised during exacerbation of chronic PID.

HVS and cervical swab for Chlamydia may help in determining the infective agent in PID.

HVS and cervical swab for Chlamydia may help in determining the infective agent in PID.

Ultrasound is helpful if there is a palpable mass or if CA-125 is elevated.

Ultrasound is helpful if there is a palpable mass or if CA-125 is elevated.

Laparoscopy is the investigation of choice for diagnosing PID, endometriosis and pelvic congestion.

Laparoscopy is the investigation of choice for diagnosing PID, endometriosis and pelvic congestion.

Further investigations, such as bowel and back imaging, might be undertaken by the specialist after referral.

Further investigations, such as bowel and back imaging, might be undertaken by the specialist after referral.

A ‘forgotten’ coil can cause cyclical pelvic pain.

A ‘forgotten’ coil can cause cyclical pelvic pain.

If the pain links with periods, establish whether it is primary or secondary dysmenorrhoea – the latter is far more likely to have a pathological cause.

If the pain links with periods, establish whether it is primary or secondary dysmenorrhoea – the latter is far more likely to have a pathological cause.

In some cases the diagnosis will remain obscure. Avoid colluding with obviously erroneous diagnoses and try to adopt a constructive approach without over-investigating the patient.

In some cases the diagnosis will remain obscure. Avoid colluding with obviously erroneous diagnoses and try to adopt a constructive approach without over-investigating the patient.

Don’t overlook non-gynaecological causes.

Don’t overlook non-gynaecological causes.

Bloating is a very common gynaecological symptom, but is characteristic of IBS. A trial of antispasmodics may aid diagnosis.

Bloating is a very common gynaecological symptom, but is characteristic of IBS. A trial of antispasmodics may aid diagnosis.

Women over 35 at first presentation and those with a mass should be referred for a gynaecological opinion.

Women over 35 at first presentation and those with a mass should be referred for a gynaecological opinion.

Misdiagnosis of PID without reliable evidence will delay the real diagnosis and lead to repeated courses of unnecessary antibiotics.

Misdiagnosis of PID without reliable evidence will delay the real diagnosis and lead to repeated courses of unnecessary antibiotics.

Ovarian cancer nearly always presents late. Have a low threshold for investigation.

Ovarian cancer nearly always presents late. Have a low threshold for investigation.

Beware the diagnosis of endometriosis. Even if confirmed at laparoscopy, remember that many women with similar findings are asymptomatic. Discuss this openly with the patient – this will help prevent dysfunction if she does not improve with anti-endometriotic treatment.

Beware the diagnosis of endometriosis. Even if confirmed at laparoscopy, remember that many women with similar findings are asymptomatic. Discuss this openly with the patient – this will help prevent dysfunction if she does not improve with anti-endometriotic treatment.

![]()

Most causes of lumps in the groin are non-urgent. Many patients do not realise this, however – the development of a groin swelling often heralds an urgent appointment, either because the patient fears sinister pathology, or because the patient knows the diagnosis but erroneously perceives it as an emergency. GPs generally welcome the problem, as diagnosis and disposal are usually straightforward.

![]()

COMMON

sebaceous cyst

sebaceous cyst

palpable lymph nodes (LNs) – ‘normal’ or secondary to an infection

palpable lymph nodes (LNs) – ‘normal’ or secondary to an infection

inguinal hernia

inguinal hernia

femoral hernia

femoral hernia

saphena varix

saphena varix

OCCASIONAL

retractile testicle

retractile testicle

abscess (local)

abscess (local)

metastatic tumour (usually as skin-fixed lymphadenopathy)

metastatic tumour (usually as skin-fixed lymphadenopathy)

hydrocele of spermatic cord

hydrocele of spermatic cord

low appendix mass, pelvic/inguinal tumour

low appendix mass, pelvic/inguinal tumour

lipoma

lipoma

RARE

abscess (psoas)

abscess (psoas)

lymphoma

lymphoma

femoral artery aneurysm

femoral artery aneurysm

neurofibroma

neurofibroma

undescended or ectopic testis

undescended or ectopic testis

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, GUM screen.

SMALL PRINT: pelvic ultrasound.

FBC and ESR/CRP useful if diffuse lymphadenopathy found, especially if no evidence of local cause or other significantly enlarged nodes found. Hb may be reduced and ESR/CRP elevated in malignancy; WCC and ESR/CRP elevated in abscess, infection and blood dyscrasias.

FBC and ESR/CRP useful if diffuse lymphadenopathy found, especially if no evidence of local cause or other significantly enlarged nodes found. Hb may be reduced and ESR/CRP elevated in malignancy; WCC and ESR/CRP elevated in abscess, infection and blood dyscrasias.

Urethral, vaginal or endocervical swabs indicated if any associated discharge and/or suspicion of STD.

Urethral, vaginal or endocervical swabs indicated if any associated discharge and/or suspicion of STD.

Pelvic ultrasound useful if pelvic mass suspected.

Pelvic ultrasound useful if pelvic mass suspected.

A large saphena varix can look very much like a small hernia. Try the Valsalva test (see Ready reckoner) and look for evidence of varicose veins.

A large saphena varix can look very much like a small hernia. Try the Valsalva test (see Ready reckoner) and look for evidence of varicose veins.

If the cause is local lymphadenopathy, look for local infective causes and don’t forget to consider STDs.

If the cause is local lymphadenopathy, look for local infective causes and don’t forget to consider STDs.

Don’t be surprised to find no abnormality – normal groin nodes in a slim person, and a normally retractile testis can cause great anxiety in patients and parents.

Don’t be surprised to find no abnormality – normal groin nodes in a slim person, and a normally retractile testis can cause great anxiety in patients and parents.

If the history suggests a hernia, but nothing is obvious on examination, get the patient to raise the intra-abdominal pressure with a vigorous cough or by raising the legs straight up while lying on the couch – and remember to examine the patient standing up, too.

If the history suggests a hernia, but nothing is obvious on examination, get the patient to raise the intra-abdominal pressure with a vigorous cough or by raising the legs straight up while lying on the couch – and remember to examine the patient standing up, too.

Femoral herniae (commoner in women) are at high risk of strangulation, so always refer.

Femoral herniae (commoner in women) are at high risk of strangulation, so always refer.

Undescended testis in the adult carries a high risk of malignancy. If the testis is not descended by the age of 1 year, then operative intervention is indicated.

Undescended testis in the adult carries a high risk of malignancy. If the testis is not descended by the age of 1 year, then operative intervention is indicated.

If lymphadenopathy is the cause, look elsewhere for abnormal lymph nodes and investigate or refer if any are found. Hard, skin-fixed nodes suggest metastatic malignancy – refer urgently.

If lymphadenopathy is the cause, look elsewhere for abnormal lymph nodes and investigate or refer if any are found. Hard, skin-fixed nodes suggest metastatic malignancy – refer urgently.

An acutely painful and irreducible groin lump suggests a strangulated or incarcerated hernia. If in any doubt, refer for urgent surgical assessment.

An acutely painful and irreducible groin lump suggests a strangulated or incarcerated hernia. If in any doubt, refer for urgent surgical assessment.