![]()

Straight out of the list of ‘Embarrassing things to see your GP about’, this is a presentation that patients love to hate. From a GP perspective, it’s one that is generally straightforward to deal with, and effective treatment can usually be offered immediately, much to the patient’s relief.

![]()

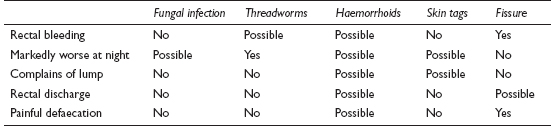

COMMON

fungal infection – tinea, thrush

fungal infection – tinea, thrush

threadworms

threadworms

haemorrhoids

haemorrhoids

perianal skin tags

perianal skin tags

anal fissure

anal fissure

OCCASIONAL

poor hygiene

poor hygiene

recurrent or chronic diarrhoea

recurrent or chronic diarrhoea

perianal warts

perianal warts

streptococcal perianal infection in children

streptococcal perianal infection in children

trauma from sexual practices – anal intercourse and foreign body insertion

trauma from sexual practices – anal intercourse and foreign body insertion

faecal incontinence, including liquid faecal seepage round impacted scybala

faecal incontinence, including liquid faecal seepage round impacted scybala

psoriasis

psoriasis

secondary to underlying diabetes

secondary to underlying diabetes

anorectal carcinoma

anorectal carcinoma

chemical irritation: defaecation after a very spicy meal (commonly experienced, rarely presented in practice), bubble baths, soaps, sexual lubricants

chemical irritation: defaecation after a very spicy meal (commonly experienced, rarely presented in practice), bubble baths, soaps, sexual lubricants

RARE

irritation from perineal decorative body piercing (the ‘Guiche’)

irritation from perineal decorative body piercing (the ‘Guiche’)

lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (affects 1 in 100 women, 3 in 10 of these have anal symptoms)

lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (affects 1 in 100 women, 3 in 10 of these have anal symptoms)

Crohn’s disease (anal/perianal fistula)

Crohn’s disease (anal/perianal fistula)

rectovaginal fistula

rectovaginal fistula

rectal prolapse

rectal prolapse

any other cause of rectal discharge or anal swellings – see appropriate chapters

any other cause of rectal discharge or anal swellings – see appropriate chapters

any serious cause of generalised pruritus – see chapter on anal itching. Rare here because pruritus ani is unlikely to be a presenting complaint

any serious cause of generalised pruritus – see chapter on anal itching. Rare here because pruritus ani is unlikely to be a presenting complaint

STDs, e.g. syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia

STDs, e.g. syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: skin swab, FBC, ESR, fasting glucose or HbA1c, proctoscopy.

SMALL PRINT: none.

In general, unless there are obvious pointers to other more serious disease, investigations would usually only follow after failure of empirical treatment.

In general, unless there are obvious pointers to other more serious disease, investigations would usually only follow after failure of empirical treatment.

Skin swab for bacteriology may help identify local infection.

Skin swab for bacteriology may help identify local infection.

FBC, ESR: may be helpful if Crohn’s disease is suspected, but only as an adjunct to referral as the appropriate management.

FBC, ESR: may be helpful if Crohn’s disease is suspected, but only as an adjunct to referral as the appropriate management.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c is essential in recurrent or prolonged cases to exclude diabetes.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c is essential in recurrent or prolonged cases to exclude diabetes.

Proctoscopy is quick to do in general practice and can yield valuable information if there is an underlying rectal cause.

Proctoscopy is quick to do in general practice and can yield valuable information if there is an underlying rectal cause.

Most patients will have attempted self-treatment before presenting in the surgery. This may not always have been appropriate, and could have made the problem worse.

Most patients will have attempted self-treatment before presenting in the surgery. This may not always have been appropriate, and could have made the problem worse.

Unless you are absolutely sure of an obvious cause, it is wise to perform a digital rectal examination to look for rectal causes.

Unless you are absolutely sure of an obvious cause, it is wise to perform a digital rectal examination to look for rectal causes.

Perianal warts imply a sexually transmitted disease contact. Refer to GUM clinic for contact tracing and treatment.

Perianal warts imply a sexually transmitted disease contact. Refer to GUM clinic for contact tracing and treatment.

Anal itching is often associated with soreness. If it precludes a rectal examination but there is no obvious primary anal cause for itching, treat symptomatically and bring the patient back to complete the assessment when more comfortable to do so. The patient is unlikely to want to return for this without understanding a clear explanation of why it is necessary.

Anal itching is often associated with soreness. If it precludes a rectal examination but there is no obvious primary anal cause for itching, treat symptomatically and bring the patient back to complete the assessment when more comfortable to do so. The patient is unlikely to want to return for this without understanding a clear explanation of why it is necessary.

Four per cent of women with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus go on to develop vulval cancer. Refer if the vulva is affected, or if treatment fails.

Four per cent of women with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus go on to develop vulval cancer. Refer if the vulva is affected, or if treatment fails.

Refer any suspicious anal lesion for biopsy.

Refer any suspicious anal lesion for biopsy.

Be confident to ask about recent sexual encounters and sexual practices if possibly relevant. Sexual history may be important.

Be confident to ask about recent sexual encounters and sexual practices if possibly relevant. Sexual history may be important.

![]()

Because of embarrassment on the part of the patient, this may well present as a ‘while I’m here’ symptom. The temptation to make a diagnosis without examination should be resisted – some of the causes (such as perianal abscesses) require urgent attention and others may, rarely, provide something of a surprise (e.g. fistulae, carcinoma).

![]()

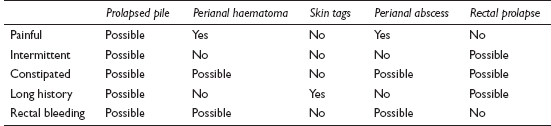

COMMON

prolapsed pile

prolapsed pile

perianal haematoma

perianal haematoma

skin tags

skin tags

perianal abscess

perianal abscess

rectal prolapse

rectal prolapse

OCCASIONAL

warts

warts

sebaceous cyst

sebaceous cyst

sentinel pile

sentinel pile

infected pilonidal sinus

infected pilonidal sinus

RARE

hidradenitis

hidradenitis

anal fistula

anal fistula

carcinoma

carcinoma

![]()

![]()

In most cases, investigation will be unnecessary. The only exceptions are warts (in which case referral to the local GUM clinic may be required to screen for sexually transmitted disease) and possible carcinoma (in which case biopsy will be performed in secondary care). Also, any suspicion of Crohn’s disease causing perianal disease would be investigated in hospital in the usual way.

This is one of those situations in which a brief history can be taken while the patient is undressing, or during the examination. Atypically for primary care, it’s the examination, rather than the history, which usually provides the definitive diagnosis.

This is one of those situations in which a brief history can be taken while the patient is undressing, or during the examination. Atypically for primary care, it’s the examination, rather than the history, which usually provides the definitive diagnosis.

If a discharge, as well as a lump, is mentioned by the patient, then abscesses, warts, prolapses and fistulae top the list of differentials.

If a discharge, as well as a lump, is mentioned by the patient, then abscesses, warts, prolapses and fistulae top the list of differentials.

The patient with an anal swelling who has obvious difficulty walking into the consulting room has either an abscess, a large perianal haematoma or strangulated prolapsed piles.

The patient with an anal swelling who has obvious difficulty walking into the consulting room has either an abscess, a large perianal haematoma or strangulated prolapsed piles.

Recurrent or multiple fistulae suggest Crohn’s disease.

Recurrent or multiple fistulae suggest Crohn’s disease.

If a prolapsed pile is very swollen and painful, it is probably strangulated, and so requires urgent surgical attention.

If a prolapsed pile is very swollen and painful, it is probably strangulated, and so requires urgent surgical attention.

A persistent, ulcerating anal swelling, especially in the middle-aged or elderly, requires urgent biopsy to exclude carcinoma.

A persistent, ulcerating anal swelling, especially in the middle-aged or elderly, requires urgent biopsy to exclude carcinoma.

![]()

This is usually severe and distressing. Because of reflex sphincteric spasm, constipation very often follows and increases the pain and suffering further. Adequate examination is also difficult for the same reason; fortunately if a PR exam is too difficult, a visual inspection can often yield the diagnosis.

![]()

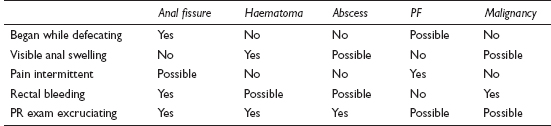

COMMON

anal fissure

anal fissure

thrombosed haemorrhoids/perianal haematoma

thrombosed haemorrhoids/perianal haematoma

perianal abscess

perianal abscess

proctalgia fugax (PF)

proctalgia fugax (PF)

anorectal malignancy

anorectal malignancy

OCCASIONAL

levator ani syndrome

levator ani syndrome

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease

coccydynia

coccydynia

descending perineum syndrome

descending perineum syndrome

prostatitis

prostatitis

ovarian cyst or tumour

ovarian cyst or tumour

solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

RARE

anal tuberculosis

anal tuberculosis

cauda equina lesion

cauda equina lesion

endometriosis

endometriosis

trauma

trauma

presacral tumours

presacral tumours

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, proctoscopy, faecal calprotectin.

SMALL PRINT: urinalysis, ultrasound, barium enema, other imaging.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC may be raised in abscess and Crohn’s disease. ESR/CRP raised in these and carcinoma.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC may be raised in abscess and Crohn’s disease. ESR/CRP raised in these and carcinoma.

Proctoscopy valuable if pain allows (specialist might also take biopsy).

Proctoscopy valuable if pain allows (specialist might also take biopsy).

Faecal calprotectin: may help in diagnosing Crohn’s disease.

Faecal calprotectin: may help in diagnosing Crohn’s disease.

Urinalysis: pus cells and blood may be present in prostatitis or invasive bladder tumour.

Urinalysis: pus cells and blood may be present in prostatitis or invasive bladder tumour.

Ultrasound of pelvis if pelvic examination reveals a mass. Barium enema may be necessary to assess possible bowel involvement. In obscure cases, specialists may request other forms of imaging.

Ultrasound of pelvis if pelvic examination reveals a mass. Barium enema may be necessary to assess possible bowel involvement. In obscure cases, specialists may request other forms of imaging.

If the patient uses dramatic language (e.g. red-hot poker) to describe fleeting pain, is otherwise well and there are no obvious abnormalities on examination, the diagnosis is likely to be proctalgia fugax.

If the patient uses dramatic language (e.g. red-hot poker) to describe fleeting pain, is otherwise well and there are no obvious abnormalities on examination, the diagnosis is likely to be proctalgia fugax.

Examine the patient – the cause is usually a thrombosed pile, anal fissure or an abscess, and these can usually be diagnosed by simple inspection.

Examine the patient – the cause is usually a thrombosed pile, anal fissure or an abscess, and these can usually be diagnosed by simple inspection.

Provide symptomatic relief but remember to deal with any underlying causes – especially constipation.

Provide symptomatic relief but remember to deal with any underlying causes – especially constipation.

Don’t forget to ask about thirst and urinary frequency: recurrent abscesses may be the first presentation of diabetes.

Don’t forget to ask about thirst and urinary frequency: recurrent abscesses may be the first presentation of diabetes.

Preceding weight loss and/or change in bowel habit should prompt a full urgent assessment with carcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease in mind.

Preceding weight loss and/or change in bowel habit should prompt a full urgent assessment with carcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease in mind.

Some perianal abscesses do not result in external swelling. If PR exam is prohibitively painful, consider this possibility – especially if the patient is febrile.

Some perianal abscesses do not result in external swelling. If PR exam is prohibitively painful, consider this possibility – especially if the patient is febrile.

In florid or recurrent perianal problems, think of Crohn’s disease as a possible cause.

In florid or recurrent perianal problems, think of Crohn’s disease as a possible cause.

Remember rarer causes in intractable, constant pain in a patient with no obvious signs on PR.

Remember rarer causes in intractable, constant pain in a patient with no obvious signs on PR.

![]()

This is a very common presenting complaint and creates a lot of anxiety in the patient. By far the likeliest causes are haemorrhoids or a fissure, but more sinister pathologies should be considered according to the clinical picture. In children, constipation causing a fissure is the most frequent cause.

![]()

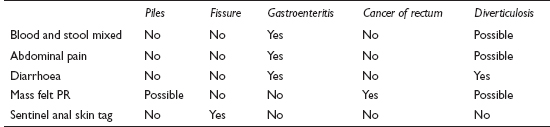

COMMON

haemorrhoids

haemorrhoids

anal fissure

anal fissure

gastroenteritis

gastroenteritis

rectal carcinoma

rectal carcinoma

diverticular disease

diverticular disease

OCCASIONAL

villous adenoma

villous adenoma

trauma (especially non-accidental injury (NAI) if in children)

trauma (especially non-accidental injury (NAI) if in children)

anticoagulant therapy

anticoagulant therapy

inflammatory bowel disease

inflammatory bowel disease

colonic carcinoma

colonic carcinoma

RARE

blood clotting disorders (including anticoagulants)

blood clotting disorders (including anticoagulants)

bowel ischaemia

bowel ischaemia

angiodysplasia

angiodysplasia

intussusception

intussusception

Meckel’s diverticulum (in children)

Meckel’s diverticulum (in children)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: proctoscopy.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, LFTs, bone biochemistry, U&E, stool for microbiology and faecal calprotectin, sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, barium enema.

SMALL PRINT: clotting screen.

FBC: check for anaemia from acute or chronic bleeding; low platelets may cause or aggravate bleeding.

FBC: check for anaemia from acute or chronic bleeding; low platelets may cause or aggravate bleeding.

ESR/CRP raised in active inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy.

ESR/CRP raised in active inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy.

If malignancy is suspected, LFT, U&E and bone biochemistry are useful early on as a baseline.

If malignancy is suspected, LFT, U&E and bone biochemistry are useful early on as a baseline.

Clotting screen: if clotting disorder a possibility; INR if on warfarin.

Clotting screen: if clotting disorder a possibility; INR if on warfarin.

Stool specimen: helpful in the presence of diarrhoea. May show evidence of infective cause (especially Campylobacter) or white cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Faecal calprotectin may be useful in diagnosing IBD.

Stool specimen: helpful in the presence of diarrhoea. May show evidence of infective cause (especially Campylobacter) or white cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Faecal calprotectin may be useful in diagnosing IBD.

Proctoscopy: helpful in primary care in visualising haemorrhoids and proctitis to confirm a clinical diagnosis.

Proctoscopy: helpful in primary care in visualising haemorrhoids and proctitis to confirm a clinical diagnosis.

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy are the most helpful investigations if significant pathology is suspected, and allow biopsy of suspicious lesions.

Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy are the most helpful investigations if significant pathology is suspected, and allow biopsy of suspicious lesions.

Barium enema good for revealing strictures related to the underlying pathology, but if diverticulosis present, may not rule out coexistent neoplasia.

Barium enema good for revealing strictures related to the underlying pathology, but if diverticulosis present, may not rule out coexistent neoplasia.

Eighty per cent of rectal tumours are within fingertip range. Always do a PR examination unless, in a child or young adult, the diagnosis is manifestly obvious from the history.

Eighty per cent of rectal tumours are within fingertip range. Always do a PR examination unless, in a child or young adult, the diagnosis is manifestly obvious from the history.

If blood is on the toilet paper and surface of the motions, the cause is likely to be palpable PR or visible on proctoscopy; if mixed in with the motions, referral for further investigation will be required to make a definite diagnosis.

If blood is on the toilet paper and surface of the motions, the cause is likely to be palpable PR or visible on proctoscopy; if mixed in with the motions, referral for further investigation will be required to make a definite diagnosis.

In young adults, the diagnosis is usually clear from the history and is likely to be haemorrhoids or a fissure. In such cases, if and when you refer, to allay anxiety, emphasise that this is for treatment rather than investigation.

In young adults, the diagnosis is usually clear from the history and is likely to be haemorrhoids or a fissure. In such cases, if and when you refer, to allay anxiety, emphasise that this is for treatment rather than investigation.

The presence of diarrhoea with rectal bleeding in young or middle-aged adults suggests gastroenteritis (especially Campylobacter) or colitis.

The presence of diarrhoea with rectal bleeding in young or middle-aged adults suggests gastroenteritis (especially Campylobacter) or colitis.

Change of bowel habit and weight loss with rectal bleeding are ominous symptoms which should prompt urgent referral.

Change of bowel habit and weight loss with rectal bleeding are ominous symptoms which should prompt urgent referral.

If a child is presented with rectal bleeding without any clear cause, consider NAI.

If a child is presented with rectal bleeding without any clear cause, consider NAI.

The presence of haemorrhoids does not necessarily clinch the diagnosis – another lesion may be present, especially in the elderly.

The presence of haemorrhoids does not necessarily clinch the diagnosis – another lesion may be present, especially in the elderly.

A brisk, painless haemorrhage in an elderly patient is likely to be caused by diverticular disease. Significant amounts of blood can be lost, so assess urgently with a view to admission.

A brisk, painless haemorrhage in an elderly patient is likely to be caused by diverticular disease. Significant amounts of blood can be lost, so assess urgently with a view to admission.

![]()

This unpleasant symptom causes considerable embarrassment and inconvenience. The presenting complaint may well be itching rather than a history of discharge or dampness. The most common causes are benign, but serious pathology is sufficiently likely to warrant thorough examination.

![]()

COMMON

haemorrhoids

haemorrhoids

anal fissure

anal fissure

rectal prolapse

rectal prolapse

proctitis

proctitis

perianal warts

perianal warts

OCCASIONAL

rectal carcinoma

rectal carcinoma

IBS

IBS

anal/perianal fistula (may be associated with Crohn’s disease)

anal/perianal fistula (may be associated with Crohn’s disease)

villous adenoma

villous adenoma

poor anal hygiene

poor anal hygiene

solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

RARE

anal tuberculosis

anal tuberculosis

anal carcinoma

anal carcinoma

STD, e.g. syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia

STD, e.g. syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia

AIDS

AIDS

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: swab if purulent.

POSSIBLE: FBC, ESR/CRP, U&E and direct visualisation techniques (see below).

SMALL PRINT: STD screen.

Anorectal swab for bacteriology if pus and local inflammation is present.

Anorectal swab for bacteriology if pus and local inflammation is present.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in inflammatory bowel disease.

FBC/ESR/CRP: WCC and ESR/CRP raised in inflammatory bowel disease.

U&E: profuse mucus discharge from a villous adenoma can cause hypokalaemia.

U&E: profuse mucus discharge from a villous adenoma can cause hypokalaemia.

Proctoscopy easily done in practice and guides management and referral.

Proctoscopy easily done in practice and guides management and referral.

Sigmoidoscopy allows definitive examination and biopsy of suspicious lesions or inflammation.

Sigmoidoscopy allows definitive examination and biopsy of suspicious lesions or inflammation.

STD screen – if STD suspected.

STD screen – if STD suspected.

This symptom is likely to be associated with embarrassment. A clinical examination is important – so help the patient overcome any reticence with a sympathetic approach.

This symptom is likely to be associated with embarrassment. A clinical examination is important – so help the patient overcome any reticence with a sympathetic approach.

Normal secretions from the anus should not be discounted – from perianal sweat glands and the anal glands themselves. This can sometimes cause a significant problem, particularly in the obese and those with poor anal hygiene.

Normal secretions from the anus should not be discounted – from perianal sweat glands and the anal glands themselves. This can sometimes cause a significant problem, particularly in the obese and those with poor anal hygiene.

In women, the source of the discharge may be unclear. Speculum examination and protoscopy may be required to resolve any doubt.

In women, the source of the discharge may be unclear. Speculum examination and protoscopy may be required to resolve any doubt.

Sexual history may be important. Don’t be coy in asking about recent sexual encounters and sexual practices if relevant.

Sexual history may be important. Don’t be coy in asking about recent sexual encounters and sexual practices if relevant.

Rectal discharge in the elderly suggests carcinoma unless proved otherwise.

Rectal discharge in the elderly suggests carcinoma unless proved otherwise.

A history of diarrhoea and abdominal pain suggests bowel pathology. Ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease is most likely in this context.

A history of diarrhoea and abdominal pain suggests bowel pathology. Ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease is most likely in this context.

Any ulcerating lesion in the perianal area other than an obvious haemorrhoid should prompt referral for biopsy.

Any ulcerating lesion in the perianal area other than an obvious haemorrhoid should prompt referral for biopsy.