![]()

Deafness is a frustrating symptom. In children it creates educational difficulties and parental worry. In adults, everyday life is fraught with difficulties, and there may be stigmatisation. Three million adults in the UK suffer some degree of persistent deafness. Congenital causes acquired in utero are not included here.

![]()

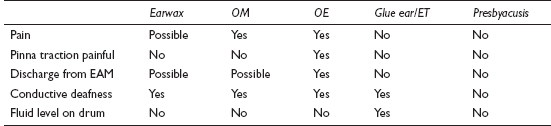

COMMON

earwax

earwax

otitis media (OM)

otitis media (OM)

otitis externa (OE)

otitis externa (OE)

glue ear (serous otitis media)/Eustachian dysfunction

glue ear (serous otitis media)/Eustachian dysfunction

presbyacusis (senile deafness)

presbyacusis (senile deafness)

OCCASIONAL

Ménière’s disease

Ménière’s disease

otosclerosis

otosclerosis

noise damage to cochlea

noise damage to cochlea

barotrauma

barotrauma

viral acoustic neuritis

viral acoustic neuritis

large nasal polyps or nasopharyngeal tumour

large nasal polyps or nasopharyngeal tumour

drugs: streptomycin, gentamicin, aspirin overdose

drugs: streptomycin, gentamicin, aspirin overdose

RARE

vascular (haemorrhage, thrombosis of cochlear vessels)

vascular (haemorrhage, thrombosis of cochlear vessels)

acoustic neuroma

acoustic neuroma

vitamin B12 deficiency

vitamin B12 deficiency

CNS causes (e.g. multiple sclerosis, cerebral secondary carcinoma)

CNS causes (e.g. multiple sclerosis, cerebral secondary carcinoma)

cholesteatoma

cholesteatoma

Paget’s disease

Paget’s disease

traumatic (e.g. to tympanic membrane or ossicles)

traumatic (e.g. to tympanic membrane or ossicles)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: (in children) audiogram and tympanometry.

POSSIBLE: ear swab.

SMALL PRINT: FBC/B12 levels, skull X-ray, further imaging.

Audiometry quantifies loss and distinguishes sensorineural from conductive hearing loss.

Audiometry quantifies loss and distinguishes sensorineural from conductive hearing loss.

Tympanometry measures the compliance of the eardrum. Fluid in the middle ear flattens the compliance curve.

Tympanometry measures the compliance of the eardrum. Fluid in the middle ear flattens the compliance curve.

Swab of ear discharge: discharge can be swabbed to guide treatment in refractory otitis externa.

Swab of ear discharge: discharge can be swabbed to guide treatment in refractory otitis externa.

FBC/B12 levels: to confirm B12 deficiency.

FBC/B12 levels: to confirm B12 deficiency.

Skull X-ray: for Paget’s disease.

Skull X-ray: for Paget’s disease.

Further imaging: e.g. CT and MRI scans may be arranged by specialist for suspected acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis or cerebral pathology.

Further imaging: e.g. CT and MRI scans may be arranged by specialist for suspected acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis or cerebral pathology.

Take parents seriously if they suspect their child is deaf. There may be no physical signs in glue ear, and tympanometry will yield the diagnosis.

Take parents seriously if they suspect their child is deaf. There may be no physical signs in glue ear, and tympanometry will yield the diagnosis.

Warn patients with otitis media that hearing may take a few weeks to return completely to normal – this saves unnecessary attendances with patients complaining that ‘The antibiotics haven’t worked’.

Warn patients with otitis media that hearing may take a few weeks to return completely to normal – this saves unnecessary attendances with patients complaining that ‘The antibiotics haven’t worked’.

In a case with no immediately alarming features and no past history of significant ear disease, it is reasonable to defer a comprehensive history and examination – instead, take a quick look at the ear canals. If the diagnosis appears to be earwax, arrange syringing. Assess in more detail only if there is no earwax or syringing doesn’t solve the problem.

In a case with no immediately alarming features and no past history of significant ear disease, it is reasonable to defer a comprehensive history and examination – instead, take a quick look at the ear canals. If the diagnosis appears to be earwax, arrange syringing. Assess in more detail only if there is no earwax or syringing doesn’t solve the problem.

Remember how to perform and interpret Rinne’s and Weber’s tests – these are invaluable in assessing the less straightforward cases.

Remember how to perform and interpret Rinne’s and Weber’s tests – these are invaluable in assessing the less straightforward cases.

Remember the possibility of acoustic neuroma if there is progressive unilateral sensorineural deafness – especially if there is accompanying tinnitus, vertigo or neurological symptoms or signs.

Remember the possibility of acoustic neuroma if there is progressive unilateral sensorineural deafness – especially if there is accompanying tinnitus, vertigo or neurological symptoms or signs.

Otherwise unexplained and persistent serous otitis media in adults may be due to nasopharyngeal carcinoma – refer for urgent examination of the nasopharyngeal space.

Otherwise unexplained and persistent serous otitis media in adults may be due to nasopharyngeal carcinoma – refer for urgent examination of the nasopharyngeal space.

Sudden onset of profound sensorineural deafness is usually viral or vascular and requires same-day ENT assessment.

Sudden onset of profound sensorineural deafness is usually viral or vascular and requires same-day ENT assessment.

Otosclerosis requires early diagnosis for effective treatment. Consider the diagnosis in otherwise unexplained conductive deafness in young adults, especially if there is a family history.

Otosclerosis requires early diagnosis for effective treatment. Consider the diagnosis in otherwise unexplained conductive deafness in young adults, especially if there is a family history.

![]()

This the commonest reason for an out-of-hours call for a child. Parental distress is often as great as the child’s, and appropriate advice can do much to relieve this – even over the telephone. Causes in adults are far more varied than for children and can originate in the pinna, ear canal, middle ear and from neighbouring structures (referred pain).

![]()

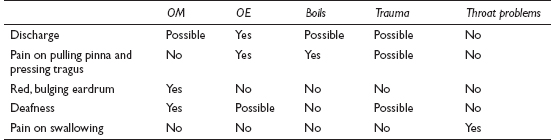

COMMON

infective otitis media (OM): bacterial/viral

infective otitis media (OM): bacterial/viral

infective otitis externa (OE): bacterial/fungal/viral

infective otitis externa (OE): bacterial/fungal/viral

boils and furuncles of the canal and pinna

boils and furuncles of the canal and pinna

trauma (especially cotton buds) and foreign bodies (including earwax)

trauma (especially cotton buds) and foreign bodies (including earwax)

throat problems: tonsillitis/pharyngitis/quinsy

throat problems: tonsillitis/pharyngitis/quinsy

OCCASIONAL

temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction

temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction

dental abscess

dental abscess

impacted molar

impacted molar

trigeminal neuralgia

trigeminal neuralgia

ear canal eczema/seborrhoeic dermatitis

ear canal eczema/seborrhoeic dermatitis

chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis externa

chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis externa

RARE

mastoiditis

mastoiditis

cervical spondylosis

cervical spondylosis

cholesteatoma

cholesteatoma

malignant disease

malignant disease

barotrauma

barotrauma

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: ear swab.

SMALL PRINT: X-rays of TMJ, teeth and mastoid bone, FBC, Paul–Bunnell test.

Swab of ear canal useful if discharge present, after failure of empirical first-line treatment.

Swab of ear canal useful if discharge present, after failure of empirical first-line treatment.

X-ray of mastoid bone excludes mastoiditis if mastoid clear – usually arranged by specialist. X-rays of TMJ and teeth are the remit of the dentist or oral surgeon.

X-ray of mastoid bone excludes mastoiditis if mastoid clear – usually arranged by specialist. X-rays of TMJ and teeth are the remit of the dentist or oral surgeon.

FBC and Paul–Bunnell test useful if glandular fever suspected. The diagnosis provides a label and guides further advice, though no specific treatment exists.

FBC and Paul–Bunnell test useful if glandular fever suspected. The diagnosis provides a label and guides further advice, though no specific treatment exists.

Further specialist investigations may include CT/MRI as the only way adequately (non-invasively) to investigate the inner ear and temporal bone anatomy.

Further specialist investigations may include CT/MRI as the only way adequately (non-invasively) to investigate the inner ear and temporal bone anatomy.

Persistent debris in the ear canal will prevent resolution of OE and mask possible underlying causes. Aural toilet is essential.

Persistent debris in the ear canal will prevent resolution of OE and mask possible underlying causes. Aural toilet is essential.

If inserting the aural speculum causes pain, the diagnosis is likely to be otitis externa or a furuncle.

If inserting the aural speculum causes pain, the diagnosis is likely to be otitis externa or a furuncle.

Don’t forget to ask about trauma – especially the use of a cotton bud. Excavating earwax with a bud tends to produce an inflamed canal and drum, mimicking infection.

Don’t forget to ask about trauma – especially the use of a cotton bud. Excavating earwax with a bud tends to produce an inflamed canal and drum, mimicking infection.

Earache can be excruciating – don’t underestimate the need for adequate analgesia while you establish and treat the cause.

Earache can be excruciating – don’t underestimate the need for adequate analgesia while you establish and treat the cause.

Consider mastoiditis if foul-smelling discharge is present for more than 10 days. Look for swelling behind the ear and downward displacement of the pinna.

Consider mastoiditis if foul-smelling discharge is present for more than 10 days. Look for swelling behind the ear and downward displacement of the pinna.

Don’t be too ready to diagnose otitis media in children – URTIs and crying inevitably result in some redness of the drum. Indiscriminate prescribing may lead to iatrogenic problems or the masking of the true diagnosis.

Don’t be too ready to diagnose otitis media in children – URTIs and crying inevitably result in some redness of the drum. Indiscriminate prescribing may lead to iatrogenic problems or the masking of the true diagnosis.

Beware the elderly patient with intractable, unexplained earache – refer to exclude a nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Beware the elderly patient with intractable, unexplained earache – refer to exclude a nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

![]()

This is often seen in swimmers and returned tropical travellers. It is frequently a sequel to water trapped behind earwax in the ear canal, which swells and encourages stasis and subsequent infection. The vast majority of cases seen settle with simple treatment, but be wary of rarer serious causes.

![]()

COMMON

boil

boil

acute suppurative otitis media (OM)

acute suppurative otitis media (OM)

infective otitis externa (OE): viral, bacterial and fungal

infective otitis externa (OE): viral, bacterial and fungal

chronic suppurative otitis media

chronic suppurative otitis media

reactive otitis externa: seborrhoeic dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis

reactive otitis externa: seborrhoeic dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis

OCCASIONAL

cholesteatoma

cholesteatoma

trauma: often a result of over-vigorous attempts to clean the ear

trauma: often a result of over-vigorous attempts to clean the ear

bullous myringitis (otitis externa haemorrhagica)

bullous myringitis (otitis externa haemorrhagica)

infection with foreign body (insects, beads in toddlers)

infection with foreign body (insects, beads in toddlers)

liquefying excess earwax

liquefying excess earwax

RARE

mastoiditis

mastoiditis

necrotising (or malignant) otitis externa

necrotising (or malignant) otitis externa

squamous and basal cell (rarer) carcinoma of the EAM

squamous and basal cell (rarer) carcinoma of the EAM

keratosis obturans (bolus of abnormally desquamated epithelium and earwax: associated with chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis)

keratosis obturans (bolus of abnormally desquamated epithelium and earwax: associated with chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis)

herpes zoster oticus

herpes zoster oticus

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: swab, urinalysis.

SMALL PRINT: skull/mastoid X-rays, CT or MRI scan, audiometry.

Swab of ear discharge: helps guide treatment in refractory cases.

Swab of ear discharge: helps guide treatment in refractory cases.

Urine for glucose: to exclude underlying diabetes if infections are recurrent (especially boils).

Urine for glucose: to exclude underlying diabetes if infections are recurrent (especially boils).

X-ray of the mastoid process will show a cloudy appearance in the mastoid air cells in mastoiditis.

X-ray of the mastoid process will show a cloudy appearance in the mastoid air cells in mastoiditis.

CT or MRI scan is the best way to investigate possible invasion of temporal bone by tumour, cholesteatoma.

CT or MRI scan is the best way to investigate possible invasion of temporal bone by tumour, cholesteatoma.

Audiometry may be required to assess baseline hearing loss in chronic OM, so improvement after definitive surgical treatment can be measured.

Audiometry may be required to assess baseline hearing loss in chronic OM, so improvement after definitive surgical treatment can be measured.

Skull X-ray: may show middle cranial fossa fracture in CSF otorrhoea (performed in hospital after significant trauma).

Skull X-ray: may show middle cranial fossa fracture in CSF otorrhoea (performed in hospital after significant trauma).

Otitis externa is often recurrent: to minimise future problems, advise the patient to avoid getting water in the ear and stop using cotton buds. Also treat any underlying skin disease.

Otitis externa is often recurrent: to minimise future problems, advise the patient to avoid getting water in the ear and stop using cotton buds. Also treat any underlying skin disease.

In the presence of ear discharge, pain on moving the tragus suggests otitis externa or a boil; in the case of the former, the patient tends to present with itching rather than pain.

In the presence of ear discharge, pain on moving the tragus suggests otitis externa or a boil; in the case of the former, the patient tends to present with itching rather than pain.

Most cases of otitis externa and media settle with empirical treatment and so don’t require a swab. Only investigate if they do not respond to first-line treatment.

Most cases of otitis externa and media settle with empirical treatment and so don’t require a swab. Only investigate if they do not respond to first-line treatment.

If the diagnosis is not certain, be sure to follow up after initial treatment to visualise the drum; if persistent discharge makes this impossible, refer to the ENT outpatients department for aural toilet and further assessment.

If the diagnosis is not certain, be sure to follow up after initial treatment to visualise the drum; if persistent discharge makes this impossible, refer to the ENT outpatients department for aural toilet and further assessment.

Heat, tenderness and swelling over the mastoid process suggests mastoiditis: refer urgently.

Heat, tenderness and swelling over the mastoid process suggests mastoiditis: refer urgently.

If ear discharge does not clear with usual therapy, refer for microsuction of debris (aural toilet) to speed resolution and exclude significant middle-ear disease.

If ear discharge does not clear with usual therapy, refer for microsuction of debris (aural toilet) to speed resolution and exclude significant middle-ear disease.

Very rarely, middle-ear infection causing discharge can progress centrally, causing, for example, meningitis or cerebral abscess – so refer immediately any patient with ear discharge who becomes confused or develops neurological signs.

Very rarely, middle-ear infection causing discharge can progress centrally, causing, for example, meningitis or cerebral abscess – so refer immediately any patient with ear discharge who becomes confused or develops neurological signs.

The use of aminoglycoside or polymyxin drops in the presence of a perforated tympanic membrane carries a risk of ototoxicity (though some specialists do use such drops even if perforation is present). When using potentially ototoxic drops, be as certain as you can about what you are treating.

The use of aminoglycoside or polymyxin drops in the presence of a perforated tympanic membrane carries a risk of ototoxicity (though some specialists do use such drops even if perforation is present). When using potentially ototoxic drops, be as certain as you can about what you are treating.

Beware severe otitis externa in elderly diabetics – it may be the necrotising (‘malignant’) form.

Beware severe otitis externa in elderly diabetics – it may be the necrotising (‘malignant’) form.

![]()

This means noises heard (nearly always subjectively) in the ears or head. They are often described as being like a whistling kettle, an engine, or in time with the heartbeat. As a short-lived phenomenon, it is very common (often with URTIs) – such cases do not usually present to the GP. More serious, persistent tinnitus occurs in up to 2% of the population. It is very distressing and can cause secondary depression and insomnia. Objective tinnitus is very rare.

![]()

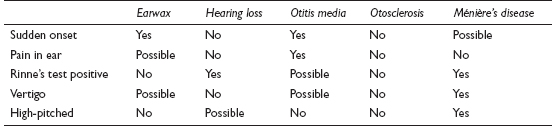

COMMON

earwax

earwax

hearing loss (20% of cases: chronic noise damage and presbyacusis)

hearing loss (20% of cases: chronic noise damage and presbyacusis)

suppurative otitis media (also chronic infection and serous OM)

suppurative otitis media (also chronic infection and serous OM)

otosclerosis

otosclerosis

Ménière’s disease

Ménière’s disease

OCCASIONAL

after a sudden loud noise (e.g. gunfire)

after a sudden loud noise (e.g. gunfire)

head injury (especially basal skull fracture)

head injury (especially basal skull fracture)

impacted wisdom teeth and TMJ dysfunction

impacted wisdom teeth and TMJ dysfunction

drugs: aspirin overdose, loop diuretics, aminoglycosides, quinine

drugs: aspirin overdose, loop diuretics, aminoglycosides, quinine

hypertension and atherosclerosis

hypertension and atherosclerosis

RARE

acoustic neuroma

acoustic neuroma

palatal myoclonus (objectively detectable)

palatal myoclonus (objectively detectable)

arteriovenous fistulae and arterial bruits (objectively detectable)

arteriovenous fistulae and arterial bruits (objectively detectable)

severe anaemia and renal failure

severe anaemia and renal failure

glomus jugulare tumours (objectively detectable)

glomus jugulare tumours (objectively detectable)

![]()

![]()

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: tympanogram, audiogram, MRI scan (all usually in secondary care).

SMALL PRINT: FBC, U&E, skull X-ray, angiography (the latter two in secondary care).

FBC and U&E: if anaemia or renal failure suspected.

FBC and U&E: if anaemia or renal failure suspected.

Tympanogram for middle-ear function and stapedial reflex threshold. Audiogram to assess hearing loss objectively.

Tympanogram for middle-ear function and stapedial reflex threshold. Audiogram to assess hearing loss objectively.

Cerebral angiography: if vascular pathology suspected.

Cerebral angiography: if vascular pathology suspected.

MRI scan: the most sensitive way to examine the inner ear and skull for structural lesions.

MRI scan: the most sensitive way to examine the inner ear and skull for structural lesions.

Skull X-ray: if associated with significant head injury.

Skull X-ray: if associated with significant head injury.

Most patients are afraid of the diagnosis of tinnitus because of its potentially debilitating nature. If the cause is clearly self-limiting or remediable, take time to reassure the patient.

Most patients are afraid of the diagnosis of tinnitus because of its potentially debilitating nature. If the cause is clearly self-limiting or remediable, take time to reassure the patient.

Have a low threshold for referral in persistent tinnitus. While no specific treatment may be available, this shows that you are taking the problem seriously, ensures that remediable problems won’t be missed and may give the patient access to masking devices.

Have a low threshold for referral in persistent tinnitus. While no specific treatment may be available, this shows that you are taking the problem seriously, ensures that remediable problems won’t be missed and may give the patient access to masking devices.

Be prepared to reassess ongoing tinnitus, as new symptoms may develop. For example, tinnitus may precede other symptoms in Ménière’s disease by months or even years.

Be prepared to reassess ongoing tinnitus, as new symptoms may develop. For example, tinnitus may precede other symptoms in Ménière’s disease by months or even years.

Depression in tinnitus has been severe enough to cause suicide. Make a thorough psychological assessment and consider a trial of antidepressants.

Depression in tinnitus has been severe enough to cause suicide. Make a thorough psychological assessment and consider a trial of antidepressants.

Think of otosclerosis in younger patients (15–30) with persistent conductive deafness – especially if there is a family history. Early diagnosis is important.

Think of otosclerosis in younger patients (15–30) with persistent conductive deafness – especially if there is a family history. Early diagnosis is important.

Progressive unilateral deafness with tinnitus could be caused by an acoustic neuroma. Exclude by referring for an MRI scan.

Progressive unilateral deafness with tinnitus could be caused by an acoustic neuroma. Exclude by referring for an MRI scan.