ABNORMAL GAIT IN ADULTS

![]()

The GP overview

Very few patients present with abnormal gait. It is more often noticed by the GP, while the patient’s complaint is usually a manifestation of the gait (e.g. unsteadiness in Parkinson’s disease) or of its cause (e.g. pain in arthritis). Congenital causes are not considered here as patients are most unlikely to present such problems to the GP.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

trauma (back and leg)

trauma (back and leg)

osteoarthritis (OA) or other painful joint problem

osteoarthritis (OA) or other painful joint problem

vestibular ataxia (vestibular neuritis, Ménière’s disease, CVA)

vestibular ataxia (vestibular neuritis, Ménière’s disease, CVA)

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease

intermittent claudication (IC)

intermittent claudication (IC)

OCCASIONAL

foot drop (peroneal nerve atrophy)

foot drop (peroneal nerve atrophy)

multiple sclerosis

multiple sclerosis

spinal nerve root pain (especially L5 and S1)

spinal nerve root pain (especially L5 and S1)

cauda equina lesions

cauda equina lesions

myasthenia gravis

myasthenia gravis

RARE

tabes dorsalis (syphilis)

tabes dorsalis (syphilis)

dystrophia myotonica

dystrophia myotonica

motor neurone disease

motor neurone disease

cerebellar ataxia

cerebellar ataxia

hysteria

hysteria

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

Most cases requiring tests will need referral to a specialist. The role of the GP in investigating these patients is therefore very limited.

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: X-ray, FBC, ESR/CRP, RA factor, uric acid.

SMALL PRINT: scans, lumbar puncture, angiography.

FBC, ESR/CRP, RA factor, uric acid: some forms of arthritis will result in an anaemia of chronic disorder. ESR/CRP may also be raised. Depending on the pattern of joint pain, RA factor and uric acid may provide useful information in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

FBC, ESR/CRP, RA factor, uric acid: some forms of arthritis will result in an anaemia of chronic disorder. ESR/CRP may also be raised. Depending on the pattern of joint pain, RA factor and uric acid may provide useful information in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

X-rays useful in bony trauma. Limited value in OA except to exclude other bony pathology.

X-rays useful in bony trauma. Limited value in OA except to exclude other bony pathology.

Syphilis serology: if tabes dorsalis suspected.

Syphilis serology: if tabes dorsalis suspected.

If neurological signs of incoordination, consider CT/MRI scan and lumbar puncture – usually arranged by the specialist.

If neurological signs of incoordination, consider CT/MRI scan and lumbar puncture – usually arranged by the specialist.

Angiography: arranged by the vascular surgeon if surgery contemplated in claudication.

Angiography: arranged by the vascular surgeon if surgery contemplated in claudication.

TOP TIPS

Look up from the notes or computer as the patient walks in – otherwise you may miss a useful clue in the patient’s gait.

Look up from the notes or computer as the patient walks in – otherwise you may miss a useful clue in the patient’s gait.

If the patient actually complains of problems walking, take your time in assessing the symptom – in particular, give the patient the opportunity to demonstrate the problem by walking him or her up and down the corridor.

If the patient actually complains of problems walking, take your time in assessing the symptom – in particular, give the patient the opportunity to demonstrate the problem by walking him or her up and down the corridor.

If the cause is not immediately apparent from the history, perform a careful neurological examination – this is a situation where there may be hard signs which contribute significantly to diagnosis.

If the cause is not immediately apparent from the history, perform a careful neurological examination – this is a situation where there may be hard signs which contribute significantly to diagnosis.

Vestibular neuritis usually settles within a few days. If patient remains ataxic, especially with persistent nystagmus, consider a central lesion and refer urgently.

Vestibular neuritis usually settles within a few days. If patient remains ataxic, especially with persistent nystagmus, consider a central lesion and refer urgently.

Numbness in both legs (saddle pattern) with back pain and incontinence suggests a cauda equina lesion. Admit urgently.

Numbness in both legs (saddle pattern) with back pain and incontinence suggests a cauda equina lesion. Admit urgently.

If the patient is ataxic and has a past history of neurological symptoms, such as paraesthesia or optic neuritis, consider multiple sclerosis.

If the patient is ataxic and has a past history of neurological symptoms, such as paraesthesia or optic neuritis, consider multiple sclerosis.

Beware of labelling the patient as hysterical – apparently bizarre gaits may signify obscure but significant neurological pathology.

Beware of labelling the patient as hysterical – apparently bizarre gaits may signify obscure but significant neurological pathology.

ABNORMAL MOVEMENTS

![]()

The GP overview

This is an infrequent cause for attendance – though the public is becoming increasingly aware of conditions such as restless legs syndrome (RLS) and Tourette’s, and their treatments. Obvious generalised seizures and tremor are not considered in this chapter but are covered elsewhere.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

RLS

RLS

myokymia (affecting orbicularis oculi muscles)

myokymia (affecting orbicularis oculi muscles)

drug induced – including choreoathetosis, dystonias, tardive dyskinesias and akathisia (drugs include l-dopa, tricyclic antidepressants, metoclopramide and antipsychotics)

drug induced – including choreoathetosis, dystonias, tardive dyskinesias and akathisia (drugs include l-dopa, tricyclic antidepressants, metoclopramide and antipsychotics)

Tourette’s

Tourette’s

simple partial seizures

simple partial seizures

OCCASIONAL

anxiety/nervous tic (common, but rarely presented to the GP)

anxiety/nervous tic (common, but rarely presented to the GP)

muscle fasciculation (e.g. benign fasciculation, motor neurone disease)

muscle fasciculation (e.g. benign fasciculation, motor neurone disease)

simple childhood tics (common, but infrequently presented)

simple childhood tics (common, but infrequently presented)

dystonias (e.g. writer’s cramp, blepharospasm, spasmodic torticollis)

dystonias (e.g. writer’s cramp, blepharospasm, spasmodic torticollis)

period leg movements during sleep

period leg movements during sleep

RARE

myoclonus

myoclonus

chorea (Sydenham’s, Huntington’s)

chorea (Sydenham’s, Huntington’s)

Wilson’s disease

Wilson’s disease

hemiballismus (e.g. post stroke)

hemiballismus (e.g. post stroke)

hysterical

hysterical

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: FBC, U&E, ferritin, B12, folate, TFT, fasting glucose or HbA1c, calcium.

POSSIBLE: CT/MRI of brain or spinal cord, EEG, EMG, nerve conduction studies.

SMALL PRINT: other specialised tests (e.g. for myoclonus and Huntington’s).

FBC, ferritin: to assess for iron deficiency in RLS.

FBC, ferritin: to assess for iron deficiency in RLS.

U&E: renal failure is a potential cause of RLS and can be implicated in partial seizures.

U&E: renal failure is a potential cause of RLS and can be implicated in partial seizures.

B12, folate: deficiencies may cause or mimic RLS.

B12, folate: deficiencies may cause or mimic RLS.

TFT: hypothyroidism may cause RLS.

TFT: hypothyroidism may cause RLS.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: diabetes may cause RLS or partial seizures.

Fasting glucose or HbA1c: diabetes may cause RLS or partial seizures.

Calcium: hypocalcaemia may be implicated in seizures.

Calcium: hypocalcaemia may be implicated in seizures.

CT/MRI of brain or spinal cord: may be required in investigation of fasciculation and seizures (usually arranged after specialist referral).

CT/MRI of brain or spinal cord: may be required in investigation of fasciculation and seizures (usually arranged after specialist referral).

EEG: for investigation of seizures.

EEG: for investigation of seizures.

Other specialised tests: usually arranged by neurologist to explore the more obscure diagnoses such as Huntington’s chorea and Wilson’s disease.

Other specialised tests: usually arranged by neurologist to explore the more obscure diagnoses such as Huntington’s chorea and Wilson’s disease.

TOP TIPS

When faced with odd and otherwise inexplicable movements of recent onset in a patient, remember to take a drug history.

When faced with odd and otherwise inexplicable movements of recent onset in a patient, remember to take a drug history.

Bear in mind that abnormal movements can be caused by a drug that the patient has been taking for some time (e.g. tardive dyskinesias).

Bear in mind that abnormal movements can be caused by a drug that the patient has been taking for some time (e.g. tardive dyskinesias).

Patients with myokymia sometimes become disproportionately anxious about the symptom, imagining all sorts of possible neurological catastrophes – they may need a lot of reassurance.

Patients with myokymia sometimes become disproportionately anxious about the symptom, imagining all sorts of possible neurological catastrophes – they may need a lot of reassurance.

Childhood tics tend to be single; the patient with the much more significant Tourette’s will probably have multiple tics.

Childhood tics tend to be single; the patient with the much more significant Tourette’s will probably have multiple tics.

Drug-induced dystonias may cause odd posturing and require prompt treatment. The diagnosis is easily overlooked – antipsychotics are common culprits, so it is easy to erroneously attribute the dystonia to psychiatric pathology.

Drug-induced dystonias may cause odd posturing and require prompt treatment. The diagnosis is easily overlooked – antipsychotics are common culprits, so it is easy to erroneously attribute the dystonia to psychiatric pathology.

Beware of the combination of personality changes and odd movements such as facial grimaces – this could be Huntington’s chorea. Also, don’t be misled by the lack of a positive family history – this background may have been concealed from the patient.

Beware of the combination of personality changes and odd movements such as facial grimaces – this could be Huntington’s chorea. Also, don’t be misled by the lack of a positive family history – this background may have been concealed from the patient.

BACK PAIN

![]()

The GP overview

Ongoing backache is a familiar presentation to all GPs, and acute back pain is one of the most common reasons for an emergency appointment in primary care. The average GP can expect about 120 consultations for this problem each year. Eighty per cent of the Western population suffer back pain at some stage in their lives: it is the largest single cause of lost working hours among both manual and sedentary workers; in the former it is an important cause of disability. Remember that many non-orthopaedic causes of back pain lie in wait, so be systematic.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

mechanical (muscular) back pain

mechanical (muscular) back pain

prolapsed lumbar disc: nerve root pain

prolapsed lumbar disc: nerve root pain

spondylosis (exacerbation)

spondylosis (exacerbation)

pyelonephritis and renal stones

pyelonephritis and renal stones

pelvic infection

pelvic infection

OCCASIONAL

the spondoarthritides (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome)

the spondoarthritides (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome)

neoplastic disease of the spine (usually secondaries), myeloma

neoplastic disease of the spine (usually secondaries), myeloma

duodenal ulcer/acute pancreatitis

duodenal ulcer/acute pancreatitis

depression and anxiety states

depression and anxiety states

vertebral fracture (often compression fracture associated with osteoporosis)

vertebral fracture (often compression fracture associated with osteoporosis)

RARE

spinal stenosis

spinal stenosis

osteomalacia

osteomalacia

aortic aneurysm

aortic aneurysm

pancreatic cancer

pancreatic cancer

spondylolisthesis

spondylolisthesis

osteomyelitis

osteomyelitis

malingering

malingering

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: none.

POSSIBLE: urinalysis, MSU, FBC, ESR/CRP, plasma electrophoresis, blood calcium, PSA.

SMALL PRINT: lumbar spine X-ray, IVU, HLA-B27, CT or MRI scan, bone scan, investigations for GI cause, ultrasound, DXA scan.

Urinalysis useful if UTI suspected: look for blood, pus and nitrite as markers of infection; confirm with MSU; blood alone suggests possible stone.

Urinalysis useful if UTI suspected: look for blood, pus and nitrite as markers of infection; confirm with MSU; blood alone suggests possible stone.

ESR/CRP elevated in malignant and inflammatory disorders.

ESR/CRP elevated in malignant and inflammatory disorders.

FBC: Hb may be reduced in malignancy; a high WCC raises the possibility of osteomyelitis.

FBC: Hb may be reduced in malignancy; a high WCC raises the possibility of osteomyelitis.

Plasma electrophoresis: paraprotein band in myeloma.

Plasma electrophoresis: paraprotein band in myeloma.

Blood calcium: elevated in myeloma and bony secondaries; reduced in osteomalacia.

Blood calcium: elevated in myeloma and bony secondaries; reduced in osteomalacia.

PSA: if disseminated prostate cancer suspected.

PSA: if disseminated prostate cancer suspected.

Lumbar spine X-ray often not useful in mechanical pain. Consider if no resolution by 6 weeks to investigate possible underlying pathology. In younger patients, it may help diagnose sacroiliitis or spondylolisthesis; in older people, it is useful to check for vertebral collapse. Generally, if imaging is required, CT or MRI may be more helpful.

Lumbar spine X-ray often not useful in mechanical pain. Consider if no resolution by 6 weeks to investigate possible underlying pathology. In younger patients, it may help diagnose sacroiliitis or spondylolisthesis; in older people, it is useful to check for vertebral collapse. Generally, if imaging is required, CT or MRI may be more helpful.

Bone scan: will detect bony secondaries and bone infection.

Bone scan: will detect bony secondaries and bone infection.

CT or MRI scan usually a specialist’s request: good for spotting spinal stenosis, significant prolapsed disc and discrete bony lesions.

CT or MRI scan usually a specialist’s request: good for spotting spinal stenosis, significant prolapsed disc and discrete bony lesions.

Investigations for GI cause might include endoscopy (for DU), serum amylase (for pancreatitis) and CT scan (for carcinoma of pancreas).

Investigations for GI cause might include endoscopy (for DU), serum amylase (for pancreatitis) and CT scan (for carcinoma of pancreas).

Ultrasound: for aortic aneurysm.

Ultrasound: for aortic aneurysm.

IVU: for recurrent pyelonephritis and possible renal or ureteric stones.

IVU: for recurrent pyelonephritis and possible renal or ureteric stones.

DEXA scan: may be required to confirm suspicion of osteoporosis.

DEXA scan: may be required to confirm suspicion of osteoporosis.

TOP TIPS

The vast majority are ‘mechanical’, and most of these improve regardless of treatment modality in 6–8 weeks; a positive and optimistic approach is important.

The vast majority are ‘mechanical’, and most of these improve regardless of treatment modality in 6–8 weeks; a positive and optimistic approach is important.

Patients often expect an X-ray. Resist requests unless appropriate – and explain why. Even if the patient doesn’t make this request, consider volunteering why you’re not ordering an X-ray, as this can help maintain confidence in the doctor–patient relationship, especially if the symptoms take some time to settle.

Patients often expect an X-ray. Resist requests unless appropriate – and explain why. Even if the patient doesn’t make this request, consider volunteering why you’re not ordering an X-ray, as this can help maintain confidence in the doctor–patient relationship, especially if the symptoms take some time to settle.

If the problem is recurrent, exclude significant pathology then explore the patient’s concerns. In simple recurrent mechanical back pain, it is worth discussing preventive measures and educating the patient for self-management of future episodes.

If the problem is recurrent, exclude significant pathology then explore the patient’s concerns. In simple recurrent mechanical back pain, it is worth discussing preventive measures and educating the patient for self-management of future episodes.

True malingering is not common, but back pain is favoured among malingerers because of its subjectivity. Beware of patients who apparently cannot straight-leg raise, yet have no problem sitting up on the couch, and patients who decline to sit down during the consultation.

True malingering is not common, but back pain is favoured among malingerers because of its subjectivity. Beware of patients who apparently cannot straight-leg raise, yet have no problem sitting up on the couch, and patients who decline to sit down during the consultation.

The traditional ‘red flags’ in back pain are thought to be of very limited use because of poor specificity and sensitivity. The only ones regarded as genuinely helpful are, for spinal fracture, older age, trauma, the presence of contusions or abrasions and steroid use, and, for spinal malignancy, a past history of cancer. Current consensus is that slavish adherence to red flags should be avoided and instead the overall clinical picture and progress assessed – although an ESR may be useful in ruling out significant disease.

The traditional ‘red flags’ in back pain are thought to be of very limited use because of poor specificity and sensitivity. The only ones regarded as genuinely helpful are, for spinal fracture, older age, trauma, the presence of contusions or abrasions and steroid use, and, for spinal malignancy, a past history of cancer. Current consensus is that slavish adherence to red flags should be avoided and instead the overall clinical picture and progress assessed – although an ESR may be useful in ruling out significant disease.

Bilateral sciatica, saddle anaesthesia and bowel and/or bladder dysfunction suggests central disc protrusion: this is a neurosurgical emergency.

Bilateral sciatica, saddle anaesthesia and bowel and/or bladder dysfunction suggests central disc protrusion: this is a neurosurgical emergency.

Consider prostatic cancer in men over 55 with atypical low back pain. Do a PR exam, together with PSA and bone assay.

Consider prostatic cancer in men over 55 with atypical low back pain. Do a PR exam, together with PSA and bone assay.

Back pain without any restriction of spinal movement, or which is not exacerbated by back movement, suggests that the source of the problem lies elsewhere – consider renal, aortic or gastrointestinal disease, or pelvic pathology in women.

Back pain without any restriction of spinal movement, or which is not exacerbated by back movement, suggests that the source of the problem lies elsewhere – consider renal, aortic or gastrointestinal disease, or pelvic pathology in women.

Tearing interscapular or lower pain in a known arteriopath suggests dissecting aortic aneurysm: admit straight away.

Tearing interscapular or lower pain in a known arteriopath suggests dissecting aortic aneurysm: admit straight away.

CRYING BABY

![]()

The GP overview

This is a very frequent reason for an out-of-hours call. A baby’s cry is almost impossible for parents to ignore. When crying continues unabated in spite of all that parents can do to settle an infant, parental distress sets in and they will turn to you for an answer and a solution.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

normal

normal

colic

colic

constipation

constipation

teething

teething

viral illness

viral illness

OCCASIONAL

otitis media or externa

otitis media or externa

severe nappy rash and/or inflamed foreskin

severe nappy rash and/or inflamed foreskin

gastroenteritis

gastroenteritis

UTI

UTI

after immunisation

after immunisation

respiratory distress – severe bronchiolitis, chest infection, croupy cough

respiratory distress – severe bronchiolitis, chest infection, croupy cough

RARE

non-accidental injury

non-accidental injury

mastoiditis

mastoiditis

meningitis, encephalitis

meningitis, encephalitis

septicaemia

septicaemia

bowel obstruction including intussusception and strangulated hernia

bowel obstruction including intussusception and strangulated hernia

appendicitis

appendicitis

osteomyelitis

osteomyelitis

testicular torsion

testicular torsion

undiagnosed birth injury, e.g. fractured clavicle

undiagnosed birth injury, e.g. fractured clavicle

congenital disorders, e.g. Hirschprung’s disease, pyloric stenosis

congenital disorders, e.g. Hirschprung’s disease, pyloric stenosis

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: none other than those performed after admission.

POSSIBLE: swab of any obvious discharge.

SMALL PRINT: see hospital investigations.

Other than a swab for obvious discharge (e.g. in otitis externa), no investigations are appropriate in general practice – if no obvious cause is found and the baby continues to be distressed, admission for observation and investigation is mandatory.

Other than a swab for obvious discharge (e.g. in otitis externa), no investigations are appropriate in general practice – if no obvious cause is found and the baby continues to be distressed, admission for observation and investigation is mandatory.

Secondary care investigations are likely to include urinalysis, MSU for bacteriology, bloods for FBC, ESR, glucose, U&E, and many others depending on the indication (e.g. CXR, AXR, lumbar puncture, blood gases).

Secondary care investigations are likely to include urinalysis, MSU for bacteriology, bloods for FBC, ESR, glucose, U&E, and many others depending on the indication (e.g. CXR, AXR, lumbar puncture, blood gases).

TOP TIPS

Babies cry on average for 1½ to 2 hours per day. Some normal babies cry more than this or for long periods for no apparent reason.

Babies cry on average for 1½ to 2 hours per day. Some normal babies cry more than this or for long periods for no apparent reason.

Remain calm and sensitive. Parents of a crying baby are often distraught, and whatever your perception of the seriousness or not of the situation, make a thorough assessment and make sure the parents understand you are taking them seriously.

Remain calm and sensitive. Parents of a crying baby are often distraught, and whatever your perception of the seriousness or not of the situation, make a thorough assessment and make sure the parents understand you are taking them seriously.

Always explain your findings and advice clearly, and make sure the parents understand you. Write things down for them if necessary. Your patient depends completely on your communication skills.

Always explain your findings and advice clearly, and make sure the parents understand you. Write things down for them if necessary. Your patient depends completely on your communication skills.

Remember the obvious – babies may cry because of tiredness, hunger, wind after feeds, boredom, and uncomfortably full nappies. Never assume that parenting skills are 100%, and do explore baby care issues that may seem to be too obvious to ask about.

Remember the obvious – babies may cry because of tiredness, hunger, wind after feeds, boredom, and uncomfortably full nappies. Never assume that parenting skills are 100%, and do explore baby care issues that may seem to be too obvious to ask about.

Babies may be unsettled and cry more than normal for a day or two after immunisation. If a baby is crying excessively for longer than 48 hours after immunisation, it is unsafe to diagnose immunisation as the cause without clinical assessment.

Babies may be unsettled and cry more than normal for a day or two after immunisation. If a baby is crying excessively for longer than 48 hours after immunisation, it is unsafe to diagnose immunisation as the cause without clinical assessment.

Telephone advice calls may be handled with careful triage and advice alone, providing there is always a fall back plan for the parents to call back or seek further advice if things do not settle rapidly. There is no substitute for a hands-on clinical assessment, and if in the slightest doubt, always see the baby as soon as possible.

Telephone advice calls may be handled with careful triage and advice alone, providing there is always a fall back plan for the parents to call back or seek further advice if things do not settle rapidly. There is no substitute for a hands-on clinical assessment, and if in the slightest doubt, always see the baby as soon as possible.

Observe in the most general way how a baby handles during examination. Irritability on handling is a very important general sign. Regardless of other examination findings, this alone can be a reason to refer for paediatric assessment.

Observe in the most general way how a baby handles during examination. Irritability on handling is a very important general sign. Regardless of other examination findings, this alone can be a reason to refer for paediatric assessment.

There is no clear physiological reason why babies should develop a fever during teething, but there is no doubt this happens in some babies, in spite of traditional medical teaching to the contrary. A fever is never high if due to teething alone. The fever of teething is usually very short-lived – less than 24 hours – while a fever caused by a viral infection can go on for several days.

There is no clear physiological reason why babies should develop a fever during teething, but there is no doubt this happens in some babies, in spite of traditional medical teaching to the contrary. A fever is never high if due to teething alone. The fever of teething is usually very short-lived – less than 24 hours – while a fever caused by a viral infection can go on for several days.

Babies cannot tell us what’s wrong, but they can tell us something’s wrong. If in any doubt about the diagnosis, seek a second opinion or a paediatric assessment. Always follow your sixth-sense, intuition or personal alarm bells. Thoughtful and experienced paediatricians will respect your feeling on this, so do not worry if you can’t justify your referral on textbook clinical criteria.

Babies cannot tell us what’s wrong, but they can tell us something’s wrong. If in any doubt about the diagnosis, seek a second opinion or a paediatric assessment. Always follow your sixth-sense, intuition or personal alarm bells. Thoughtful and experienced paediatricians will respect your feeling on this, so do not worry if you can’t justify your referral on textbook clinical criteria.

Be aware of the possibility of non-accidental injury as a cause for the baby crying. If you detect unusual anxiety, or unusual emotional detachment from the calling parent, make sure you see the baby and examine it thoroughly.

Be aware of the possibility of non-accidental injury as a cause for the baby crying. If you detect unusual anxiety, or unusual emotional detachment from the calling parent, make sure you see the baby and examine it thoroughly.

A baby that has been crying a lot and goes on to become lethargic (as opposed to a normal calm state) is probably very ill. Even if you are unsure of the diagnosis, follow your intuition and arrange a paediatric opinion.

A baby that has been crying a lot and goes on to become lethargic (as opposed to a normal calm state) is probably very ill. Even if you are unsure of the diagnosis, follow your intuition and arrange a paediatric opinion.

A constantly bulging fontanelle is always an indication for immediate paediatric referral.

A constantly bulging fontanelle is always an indication for immediate paediatric referral.

Be sure to observe and note the general muscular tone of a crying baby. Constant stiffness or floppiness are ominous signs and immediate referral is indicated.

Be sure to observe and note the general muscular tone of a crying baby. Constant stiffness or floppiness are ominous signs and immediate referral is indicated.

DELAYED PUBERTY

![]()

The GP overview

Delayed puberty means delayed development of all the secondary sexual characteristics. It is a rare but serious symptom. In girls, it is usually presented as a delayed menarche (failure to menstruate by the age of 16), though it may present as failure to develop other secondary sexual characteristics from the age of 14. In boys, the defined age is 15. The following is a selection of the more important causes. (Remember that the subheadings Common, Occasional, Rare are relative – overall, this is a rare presenting symptom.)

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

constitutional (50% of cases in boys, 16% of cases in girls)

constitutional (50% of cases in boys, 16% of cases in girls)

hyperthyroidism

hyperthyroidism

Turner’s syndrome

Turner’s syndrome

anorexia nervosa (1% of all girls in Western countries)

anorexia nervosa (1% of all girls in Western countries)

hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) deficiency (e.g. Noonan’s and Kallmann’s syndrome)

hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) deficiency (e.g. Noonan’s and Kallmann’s syndrome)

OCCASIONAL

space-occupying hypothalamo-pituitary lesion (various types)

space-occupying hypothalamo-pituitary lesion (various types)

chronic disease (e.g. diabetes, renal failure, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease)

chronic disease (e.g. diabetes, renal failure, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease)

hyperprolactinaemia

hyperprolactinaemia

adrenal disease: congenital adrenal hyperplasia and Cushing’s disease

adrenal disease: congenital adrenal hyperplasia and Cushing’s disease

drugs (e.g. thyroxine, chemotherapy (both sexes); androgens, anabolic steroids (females only))

drugs (e.g. thyroxine, chemotherapy (both sexes); androgens, anabolic steroids (females only))

radiotherapy

radiotherapy

growth hormone deficiency

growth hormone deficiency

RARE

other ovarian problems (e.g. pure dysgenesis, autoimmune disease)

other ovarian problems (e.g. pure dysgenesis, autoimmune disease)

hypothyroidism if autoimmune (otherwise associated with early puberty)

hypothyroidism if autoimmune (otherwise associated with early puberty)

pure gonadal dysgenesis

pure gonadal dysgenesis

maldescent of the testes (rare nowadays: usually detected early)

maldescent of the testes (rare nowadays: usually detected early)

trauma, infection and granulomas of hypothalamus/pituitary

trauma, infection and granulomas of hypothalamus/pituitary

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

Cases requiring investigation are likely to need referral to a paediatrician or endocrinologist. The role of the GP is therefore limited. A few basic tests might be arranged in primary care in probable constitutional cases, mainly to exclude underlying disease and ‘reassure’ patient, parents and doctor (e.g. urinalysis, FBC, U&E, TFT). More complex investigations in secondary care might include CT scanning (tumours), ultrasound of pelvis (to examine ovaries and search for nonpalpable gonads), chromosomal analysis and various tests of endocrine function.

TOP TIPS

Delayed puberty causes worry for parents and often misery for children, who may be teased or bullied by their adolescent peers. Take their concerns seriously from the outset.

Delayed puberty causes worry for parents and often misery for children, who may be teased or bullied by their adolescent peers. Take their concerns seriously from the outset.

Remember to take a family history: constitutional delayed puberty often runs in families.

Remember to take a family history: constitutional delayed puberty often runs in families.

The majority of children brought with ‘delayed puberty’ will be normal, with their parents either not recognising that secondary sexual characteristics are developing or not appreciating the age range which is normal for pubertal development.

The majority of children brought with ‘delayed puberty’ will be normal, with their parents either not recognising that secondary sexual characteristics are developing or not appreciating the age range which is normal for pubertal development.

Distinguish between delayed puberty and primary amenorrhoea with otherwise normal pubertal development. The latter has different causes (e.g. vaginal atresia, cycle initiation defect and, very rarely, testicular feminisation).

Distinguish between delayed puberty and primary amenorrhoea with otherwise normal pubertal development. The latter has different causes (e.g. vaginal atresia, cycle initiation defect and, very rarely, testicular feminisation).

Although it accounts for 50% of male cases, do not diagnose constitutional delayed puberty in boys in the presence of a very small penis or anosmia – in these situations, an underlying disease is likely.

Although it accounts for 50% of male cases, do not diagnose constitutional delayed puberty in boys in the presence of a very small penis or anosmia – in these situations, an underlying disease is likely.

More than 80% of cases in girls have a pathological cause, so investigation is the rule.

More than 80% of cases in girls have a pathological cause, so investigation is the rule.

Short stature, malaise and symptoms or signs of hypothyroidism suggest an underlying disorder of the hypothalamus and/or pituitary.

Short stature, malaise and symptoms or signs of hypothyroidism suggest an underlying disorder of the hypothalamus and/or pituitary.

EPISODIC LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

![]()

The GP overview

The terminology in this area can be very confusing with words like ‘syncope’ and ‘faints’ being used imprecisely. Episodic loss of consciousness can occur in any age group, though it tends to be commoner in the elderly. It is a frightening experience for the patient, and it demands thorough examination, investigation and a low threshold for referral. For the GP, the differential widens the older the patient – and cardiac causes should not be overlooked in the elderly.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

vasovagal attacks (faints)

vasovagal attacks (faints)

paroxysmal arrhythmia, e.g. Stokes–Adams attacks, sinus bradycardia, SVT

paroxysmal arrhythmia, e.g. Stokes–Adams attacks, sinus bradycardia, SVT

epilepsy (various forms)

epilepsy (various forms)

hypoglycaemia

hypoglycaemia

orthostatic hypotension

orthostatic hypotension

OCCASIONAL

cardiac structural lesion, e.g. aortic stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy,

cardiac structural lesion, e.g. aortic stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy,

pulmonary stenosis

micturition and cough syncope

micturition and cough syncope

sleep apnoea

sleep apnoea

Valsalva-induced syncope, e.g. weightlifting

Valsalva-induced syncope, e.g. weightlifting

pseudoseizures

pseudoseizures

RARE

narcolepsy

narcolepsy

carotid sinus syncope

carotid sinus syncope

hyperventilation

hyperventilation

subclavian steal syndrome

subclavian steal syndrome

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: FBC; ECG (especially in elderly); if probable epilepsy, also EEG and CT scan.

POSSIBLE: glucometer, 24 h ECG.

SMALL PRINT: echocardiography, tilt-table testing.

Glucometer ‘on the scene’ gives diagnosis of hypoglycaemia.

Glucometer ‘on the scene’ gives diagnosis of hypoglycaemia.

FBC: anaemia will exacerbate any form of syncope and TIAs.

FBC: anaemia will exacerbate any form of syncope and TIAs.

Standard ECG may reveal signs of ischaemia and heart block; 24 h ECG more useful for definitive diagnosis of arrhythmia.

Standard ECG may reveal signs of ischaemia and heart block; 24 h ECG more useful for definitive diagnosis of arrhythmia.

CT scan and EEG essential if previously undiagnosed epilepsy suspected.

CT scan and EEG essential if previously undiagnosed epilepsy suspected.

Echocardiography: if structural cardiac problem suspected.

Echocardiography: if structural cardiac problem suspected.

Tilt-table testing: for unexplained syncope to assess susceptibility to vasovagal episodes.

Tilt-table testing: for unexplained syncope to assess susceptibility to vasovagal episodes.

TOP TIPS

The key to diagnosis is an accurate history. This may not be available from the patient, so make a real effort to obtain an eyewitness account.

The key to diagnosis is an accurate history. This may not be available from the patient, so make a real effort to obtain an eyewitness account.

In younger patients, the diagnosis is likely to lie between a vasovagal attack and a fit; in the middle-aged and elderly, the differential is much wider and will include, for example, arrhythmias and orthostatic hypotension.

In younger patients, the diagnosis is likely to lie between a vasovagal attack and a fit; in the middle-aged and elderly, the differential is much wider and will include, for example, arrhythmias and orthostatic hypotension.

Episodic loss of consciousness is a symptom which merits diligent assessment. An accurate diagnosis has implications not only for the individual’s health, but also for employment and driving.

Episodic loss of consciousness is a symptom which merits diligent assessment. An accurate diagnosis has implications not only for the individual’s health, but also for employment and driving.

Remember that, with a vasovagal episode, patients remaining upright (e.g. sitting or in a crowd) may develop tonic–clonic movements which mimic a fit.

Remember that, with a vasovagal episode, patients remaining upright (e.g. sitting or in a crowd) may develop tonic–clonic movements which mimic a fit.

Unlike in syncope or seizures, the eyes are usually closed in pseudoseizures.

Unlike in syncope or seizures, the eyes are usually closed in pseudoseizures.

An eyewitness account that the patient looked as though he or she had died, together with marked facial flushing on recovery, is characteristic of Stokes–Adams attacks. These can be fatal, so early diagnosis is important.

An eyewitness account that the patient looked as though he or she had died, together with marked facial flushing on recovery, is characteristic of Stokes–Adams attacks. These can be fatal, so early diagnosis is important.

Discovery of an aortic stenotic murmur should prompt urgent referral. Severe aortic stenosis can cause sudden cardiac death.

Discovery of an aortic stenotic murmur should prompt urgent referral. Severe aortic stenosis can cause sudden cardiac death.

Red flags suggesting a possible cardiac cause include a family history of sudden cardiac death, syncope during exercise and an abnormal ECG.

Red flags suggesting a possible cardiac cause include a family history of sudden cardiac death, syncope during exercise and an abnormal ECG.

Syncope caused by neck pressure or head movement could be carotid sinus syncope – if recurrent, this will require a pacemaker.

Syncope caused by neck pressure or head movement could be carotid sinus syncope – if recurrent, this will require a pacemaker.

EXCESSIVE SWEATING

![]()

The GP overview

Under normal conditions, 800 mL of water is lost daily as insensible loss, mostly in sweat. Excessive sweating can at least double this figure. As a symptom, it is normally part of a package of other problems – it is unusual for the patient to present with excessive sweating in isolation.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

menopause

menopause

anxiety

anxiety

infections (common, acute)

infections (common, acute)

hypoglycaemia: may be reactive, i.e. non-diabetic

hypoglycaemia: may be reactive, i.e. non-diabetic

hyperthyroidism

hyperthyroidism

OCCASIONAL

drugs: alcohol, tricyclic antidepressants, pilocarpine

drugs: alcohol, tricyclic antidepressants, pilocarpine

alcohol and drug withdrawal

alcohol and drug withdrawal

shock/syncope

shock/syncope

intense pain

intense pain

hyperhidrosis

hyperhidrosis

other infections, e.g. TB, HIV, endocarditis, brucellosis

other infections, e.g. TB, HIV, endocarditis, brucellosis

RARE

malignancy (e.g. lymphoma)

malignancy (e.g. lymphoma)

organic nerve lesions: brain tumours, spinal cord injury (sweating is localised to dermatome involved)

organic nerve lesions: brain tumours, spinal cord injury (sweating is localised to dermatome involved)

pachydermoperiostosis: localised to skin folds of forehead and extremities

pachydermoperiostosis: localised to skin folds of forehead and extremities

hyperpituitarism/acromegaly

hyperpituitarism/acromegaly

rare vasoactive tumours: phaeochromocytoma, carcinoid

rare vasoactive tumours: phaeochromocytoma, carcinoid

connective tissue disorders

connective tissue disorders

![]()

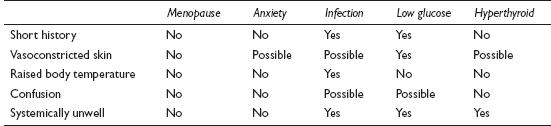

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: FBC, ESR/CRP, TFT.

POSSIBLE: FSH/LH, LFT, glucose.

SMALL PRINT: autoimmune screen, CXR, tests for uncommon infections, 24-hour urinary catecholamines, CT/MRI scan.

FBC/ESR/CRP: ESR/CRP and WCC raised in infection. Raised ESR/CRP and anaemia possible in lymphoma and other malignancies.

FBC/ESR/CRP: ESR/CRP and WCC raised in infection. Raised ESR/CRP and anaemia possible in lymphoma and other malignancies.

TFTs: may reveal thyrotoxicosis as a cause of chronic sweating.

TFTs: may reveal thyrotoxicosis as a cause of chronic sweating.

Glucose: in reactive hypoglycaemia only useful at the time of the sweating.

Glucose: in reactive hypoglycaemia only useful at the time of the sweating.

FSH/LH: helps if diagnosis of menopause in doubt.

FSH/LH: helps if diagnosis of menopause in doubt.

LFT: may reveal high alcohol intake.

LFT: may reveal high alcohol intake.

CXR might reveal occult infection (especially TB) or malignancy.

CXR might reveal occult infection (especially TB) or malignancy.

Tests for uncommon infections, e.g. blood test for HIV, echocardiography for endocarditis.

Tests for uncommon infections, e.g. blood test for HIV, echocardiography for endocarditis.

Autoimmune screen: may help in confirming diagnosis of connective tissue disease.

Autoimmune screen: may help in confirming diagnosis of connective tissue disease.

24 h urinary catecholamines traditionally used to look for phaeochromocytoma, but low specificity makes CT/MRI scan more useful.

24 h urinary catecholamines traditionally used to look for phaeochromocytoma, but low specificity makes CT/MRI scan more useful.

TOP TIPS

Length of history is very helpful – short-term sweating is likely to have an apparent, acute cause; if long-term, the diagnosis is more likely to be constitutional or anxiety; in the medium-term, the differential diagnosis is much wider.

Length of history is very helpful – short-term sweating is likely to have an apparent, acute cause; if long-term, the diagnosis is more likely to be constitutional or anxiety; in the medium-term, the differential diagnosis is much wider.

Anxiety rarely causes night sweats.

Anxiety rarely causes night sweats.

Do not underestimate the potentially devastating effect of hyperhidrosis.

Do not underestimate the potentially devastating effect of hyperhidrosis.

Lack of fever does not exclude infection. In some infections (e.g. TB, brucellosis) – and lymphoma – sweating can be out of phase with fever.

Lack of fever does not exclude infection. In some infections (e.g. TB, brucellosis) – and lymphoma – sweating can be out of phase with fever.

If the problem is persistent, a full examination is advisable, paying attention to the lymph nodes, liver and spleen. If no cause is apparent, have a low threshold for investigations or referral, particularly if the patient is unwell or losing weight.

If the problem is persistent, a full examination is advisable, paying attention to the lymph nodes, liver and spleen. If no cause is apparent, have a low threshold for investigations or referral, particularly if the patient is unwell or losing weight.

Consider unusual infections in the recently returned traveller (e.g. TB, typhoid).

Consider unusual infections in the recently returned traveller (e.g. TB, typhoid).

Episodic skin flushing (especially provoked by alcohol) with diarrhoea and breathlessness is likely to be caused by anxiety – but don’t forget carcinoid syndrome as a rare possibility.

Episodic skin flushing (especially provoked by alcohol) with diarrhoea and breathlessness is likely to be caused by anxiety – but don’t forget carcinoid syndrome as a rare possibility.

FAILURE TO THRIVE

![]()

The GP overview

Failure to thrive is defined as the failure of a child to maintain the normal rate of growth for its age and gender. A logical and systematic approach is essential to navigate through the vast differential diagnosis list.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

There are very many causes of failure to thrive. To produce a workable list, we have given broad categories and emphasised within them the most common causes.

COMMON

normal – the genetic components of height and weight kick in during the first 2 years, so babies of small parents may cross the centiles and appear to be ‘dropping off’

normal – the genetic components of height and weight kick in during the first 2 years, so babies of small parents may cross the centiles and appear to be ‘dropping off’

neglect (emotional and physical)

neglect (emotional and physical)

feeding problems (inadequate or inappropriate feeding, physical causes, e.g. cleft palate)

feeding problems (inadequate or inappropriate feeding, physical causes, e.g. cleft palate)

vomiting from any cause (gastro-oesophageal reflux common, other causes such as pyloric stenosis rarer)

vomiting from any cause (gastro-oesophageal reflux common, other causes such as pyloric stenosis rarer)

malabsorption – including cow’s milk intolerance (lactose or cow’s milk protein intolerance), coeliac disease

malabsorption – including cow’s milk intolerance (lactose or cow’s milk protein intolerance), coeliac disease

OCCASIONAL

recurrent infections, e.g. UTI, frequent viral illnesses

recurrent infections, e.g. UTI, frequent viral illnesses

metabolic/endocrine causes, e.g. diabetes, hypo- and hyperthyroidism

metabolic/endocrine causes, e.g. diabetes, hypo- and hyperthyroidism

common chronic infection (UTI, gastroenteritis)

common chronic infection (UTI, gastroenteritis)

syndromes, e.g. Turner’s, Down’s (though growth can follow centiles normally)

syndromes, e.g. Turner’s, Down’s (though growth can follow centiles normally)

intrauterine growth retardation

intrauterine growth retardation

premature delivery with complications

premature delivery with complications

toxicity during pregnancy, e.g. maternal smoking, alcohol, cocaine and amphetamines

toxicity during pregnancy, e.g. maternal smoking, alcohol, cocaine and amphetamines

maternal medication or infection during pregnancy

maternal medication or infection during pregnancy

RARE

serious chronic disease, e.g. cerebral palsy, hepatic, cardiac or renal failure

serious chronic disease, e.g. cerebral palsy, hepatic, cardiac or renal failure

severe chronic asthma

severe chronic asthma

malignancy

malignancy

rare (in UK) chronic infection: TB, congenital HIV, parasites

rare (in UK) chronic infection: TB, congenital HIV, parasites

Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy

Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy

cystic fibrosis

cystic fibrosis

inborn errors of metabolism

inborn errors of metabolism

rare causes of infant feeding difficulties, e.g. hypotonia, micrognathia, Prader–Willi syndrome

rare causes of infant feeding difficulties, e.g. hypotonia, micrognathia, Prader–Willi syndrome

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: urinalysis, MSU, FBC, U&E, LFTs, thyroid function tests, coeliac screen, stool studies.

POSSIBLE: immunoglobulins.

SMALL PRINT: PPD skin test, radiological studies, sweat chloride test, growth hormone levels, HIV testing.

Urinalysis and MSU to seek evidence of UTI.

Urinalysis and MSU to seek evidence of UTI.

FBC may reveal both the effects of malnutrition (anaemia) and possible causes of failure to thrive, e.g. a raised white cell count indicating chronic infection.

FBC may reveal both the effects of malnutrition (anaemia) and possible causes of failure to thrive, e.g. a raised white cell count indicating chronic infection.

U&E and LFTs can both be markers of reduced metabolic function (reduced urea, creatinine and albumin, and reduced liver enzyme activity) or the signs of primary renal or hepatic disease.

U&E and LFTs can both be markers of reduced metabolic function (reduced urea, creatinine and albumin, and reduced liver enzyme activity) or the signs of primary renal or hepatic disease.

Thyroid function tests: essential and simple to detect over- or underactive thyroid.

Thyroid function tests: essential and simple to detect over- or underactive thyroid.

Coeliac screen and stool studies: for malabsorption (and look too for parasites, e.g. helminths or giardiasis).

Coeliac screen and stool studies: for malabsorption (and look too for parasites, e.g. helminths or giardiasis).

Immunoglobulins: different patterns and levels of different immunoglobulin classes are associated with a vast range of infective, autoimmune and neoplastic conditions.

Immunoglobulins: different patterns and levels of different immunoglobulin classes are associated with a vast range of infective, autoimmune and neoplastic conditions.

Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test (for tuberculosis) is also known as the Mantoux test. A positive reaction to the injected tuberculin PPD may indicate current TB infection, or previous exposure.

Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test (for tuberculosis) is also known as the Mantoux test. A positive reaction to the injected tuberculin PPD may indicate current TB infection, or previous exposure.

Radiological studies: bone age may be helpful to distinguish genetic short stature from constitutional delay of growth.

Radiological studies: bone age may be helpful to distinguish genetic short stature from constitutional delay of growth.

Sweat chloride test is a reliable diagnostic test for cystic fibrosis, which affects 1 in 2500 infants.

Sweat chloride test is a reliable diagnostic test for cystic fibrosis, which affects 1 in 2500 infants.

Growth hormone levels. Growth hormone deficiency affects about 1 in 3500 children.

Growth hormone levels. Growth hormone deficiency affects about 1 in 3500 children.

HIV testing if vertical transmission of HIV is suspected.

HIV testing if vertical transmission of HIV is suspected.

TOP TIPS

Remember that 3% of normal infants fall below the third centile. Ask about height of other parent and grandparents in an otherwise healthy child. A constitutionally small child’s growth will still follow the centile curves albeit from a low starting point.

Remember that 3% of normal infants fall below the third centile. Ask about height of other parent and grandparents in an otherwise healthy child. A constitutionally small child’s growth will still follow the centile curves albeit from a low starting point.

A third of children with psychosocial failure to thrive are developmentally delayed and have social and emotional problems.

A third of children with psychosocial failure to thrive are developmentally delayed and have social and emotional problems.

If parents are small, and there is no other sign of an underlying problem, it is safe to wait and observe the baby with regular weight measurements. The baby should return to running parallel with the centiles after the second year.

If parents are small, and there is no other sign of an underlying problem, it is safe to wait and observe the baby with regular weight measurements. The baby should return to running parallel with the centiles after the second year.

A diagnosis of a non-organic cause of failure to thrive may be the earliest indication of a serious parent–child interaction dysfunction.

A diagnosis of a non-organic cause of failure to thrive may be the earliest indication of a serious parent–child interaction dysfunction.

Non-organically caused failure to thrive in the first year of life has an ominous prognosis. There is a high likelihood of ongoing child abuse in this group.

Non-organically caused failure to thrive in the first year of life has an ominous prognosis. There is a high likelihood of ongoing child abuse in this group.

If child abuse is suspected, refer to paediatrics urgently – by admission to hospital.

If child abuse is suspected, refer to paediatrics urgently – by admission to hospital.

The younger and more ill a child or baby is at presentation with failure to thrive, the more urgently assessment and action are required.

The younger and more ill a child or baby is at presentation with failure to thrive, the more urgently assessment and action are required.

A study has shown that half of cases of organic failure to thrive were also associated with a contributory psychosocial factor. Be alert to the fact that this can be a multifactorial condition.

A study has shown that half of cases of organic failure to thrive were also associated with a contributory psychosocial factor. Be alert to the fact that this can be a multifactorial condition.

FALLS WITH NO LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

![]()

The GP overview

This is a common problem in the elderly and may represent an acute or chronic problem. A home visit is often necessary and can be very valuable, assisting diagnosis and management decisions.

NOTE: The term ‘drop attacks’ is inconsistently defined in the literature as ‘falls with no loss of consciousness’, ‘falls with loss of consciousness’ or may be regarded as a distinct diagnostic entity rather than a symptom. It is a term best left unused.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

orthostatic hypotension

orthostatic hypotension

brainstem ischaemia (vertebrobasilar insufficiency)

brainstem ischaemia (vertebrobasilar insufficiency)

iatrogenic (e.g. phenothiazines, hypoglycaemics, tricyclics and hypotensives)

iatrogenic (e.g. phenothiazines, hypoglycaemics, tricyclics and hypotensives)

postural instability (osteoarthritis, quadriceps weakness)

postural instability (osteoarthritis, quadriceps weakness)

any acute illness (e.g. sepsis, CVA)

any acute illness (e.g. sepsis, CVA)

OCCASIONAL

lack of concentration (tripping over mats etc.)

lack of concentration (tripping over mats etc.)

visual disturbance

visual disturbance

acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol misuse

acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol misuse

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease

cardiac arrhythmias

cardiac arrhythmias

any cause of vertigo (e.g. labyrinthitis, Ménière’s disease) or non-specific dizziness (e.g. anaemia)

any cause of vertigo (e.g. labyrinthitis, Ménière’s disease) or non-specific dizziness (e.g. anaemia)

RARE

hypothyroidism

hypothyroidism

hydrocephalus

hydrocephalus

third ventricular tumour

third ventricular tumour

diabetic autonomic neuropathy

diabetic autonomic neuropathy

aortic stenosis

aortic stenosis

painless (‘silent’) myocardial infarction

painless (‘silent’) myocardial infarction

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

LIKELY: urinalysis, FBC.

POSSIBLE: TFT, LFT, ECG (or 24 h ECG).

SMALL PRINT: CT scan, echocardiography.

Urinalysis for glucose may reveal underlying diabetes – a major cause of autonomic neuropathy – or evidence of UTI.

Urinalysis for glucose may reveal underlying diabetes – a major cause of autonomic neuropathy – or evidence of UTI.

FBC: anaemia will exacerbate any cause of postural hypotension, or may itself cause dizziness. Sepsis is suggested by a raised WCC. A high MCV may be a useful pointer to alcohol misuse or hypothyroidism.

FBC: anaemia will exacerbate any cause of postural hypotension, or may itself cause dizziness. Sepsis is suggested by a raised WCC. A high MCV may be a useful pointer to alcohol misuse or hypothyroidism.

TFT: hypothyroidism is common in the elderly and develops insidiously.

TFT: hypothyroidism is common in the elderly and develops insidiously.

LFT: for evidence (γGT) of alcohol misuse.

LFT: for evidence (γGT) of alcohol misuse.

ECG or 24 h ECG is useful to identify an arrhythmia, conduction defect or MI.

ECG or 24 h ECG is useful to identify an arrhythmia, conduction defect or MI.

CT scanning (e.g. for tumours or hydrocephalus) or echocardiography (for aortic stenosis) may be arranged by the specialist after referral.

CT scanning (e.g. for tumours or hydrocephalus) or echocardiography (for aortic stenosis) may be arranged by the specialist after referral.

TOP TIPS

Failure to observe the patient’s gait may mean that significant diagnoses, such as Parkinson’s disease, are missed.

Failure to observe the patient’s gait may mean that significant diagnoses, such as Parkinson’s disease, are missed.

Recurrent falls in the elderly are often caused by a combination of factors, such as failing vision, poor lighting and trip hazards at home. A home assessment may give valuable clues.

Recurrent falls in the elderly are often caused by a combination of factors, such as failing vision, poor lighting and trip hazards at home. A home assessment may give valuable clues.

In the acute situation, management may depend more upon the ability of the patient to remain safely at home (e.g. social support) rather than the precise diagnosis.

In the acute situation, management may depend more upon the ability of the patient to remain safely at home (e.g. social support) rather than the precise diagnosis.

Don’t underestimate the importance of what you prescribe in causing morbidity. Attempt to reduce polypharmacy and review therapy regularly.

Don’t underestimate the importance of what you prescribe in causing morbidity. Attempt to reduce polypharmacy and review therapy regularly.

In dealing with this problem, don’t forget to look for cause and effect: the aetiology of the falls and any significant injuries sustained.

In dealing with this problem, don’t forget to look for cause and effect: the aetiology of the falls and any significant injuries sustained.

Sudden onset of falls in the previously well elderly patient is likely to represent acute pathology – have a low threshold for investigation or admission.

Sudden onset of falls in the previously well elderly patient is likely to represent acute pathology – have a low threshold for investigation or admission.

Gradual onset of recurrent falls is often multifactorial in the elderly; in younger patients, specific underlying disease is more likely, so refer for investigation.

Gradual onset of recurrent falls is often multifactorial in the elderly; in younger patients, specific underlying disease is more likely, so refer for investigation.

Evidence of injury (e.g. bruises or fractures) and multiple attendance slips from A&E department indicate either a very frail, vulnerable elderly person or significant underlying illness.

Evidence of injury (e.g. bruises or fractures) and multiple attendance slips from A&E department indicate either a very frail, vulnerable elderly person or significant underlying illness.

THE FEBRILE CHILD

![]()

The GP overview

This symptom probably generates more GP advice calls and parental anxiety than any other. It is nearly always caused by an infection of some kind. The list of culprits is so vast that we have concentrated on the common and occasional ones more likely to be seen in general practice in the UK.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

non-specific viral URTI, e.g. colds, flu-type illness, pharyngitis, tracheitis

non-specific viral URTI, e.g. colds, flu-type illness, pharyngitis, tracheitis

gastroenteritis

gastroenteritis

otitis media

otitis media

tonsillitis

tonsillitis

chest infection

chest infection

OCCASIONAL

urinary tract infection

urinary tract infection

bronchiolitis

bronchiolitis

croup

croup

common viral exanthems, e.g. chickenpox, roseola, hand, foot and mouth, fifth disease

common viral exanthems, e.g. chickenpox, roseola, hand, foot and mouth, fifth disease

appendicitis

appendicitis

cellulitis (especially orbital) and other significant skin infections, e.g. abscess, scalded skin

cellulitis (especially orbital) and other significant skin infections, e.g. abscess, scalded skin

glandular fever

glandular fever

post-immunisation

post-immunisation

giardiasis

giardiasis

RARE

meningitis/meningococcal septicaemia

meningitis/meningococcal septicaemia

encephalitis

encephalitis

hepatitis

hepatitis

AIDS

AIDS

rare exanthems, e.g. measles, rubella

rare exanthems, e.g. measles, rubella

mumps

mumps

acute epiglottitis

acute epiglottitis

atypical infections, e.g. brucellosis, listeriosis, Lyme disease, cat scratch fever

atypical infections, e.g. brucellosis, listeriosis, Lyme disease, cat scratch fever

tuberculosis

tuberculosis

protozoal diseases, e.g. cryptosporidium, leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis, malaria

protozoal diseases, e.g. cryptosporidium, leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis, malaria

septic arthritis, osteomyelitis

septic arthritis, osteomyelitis

Kawasaki’s disease

Kawasaki’s disease

![]()

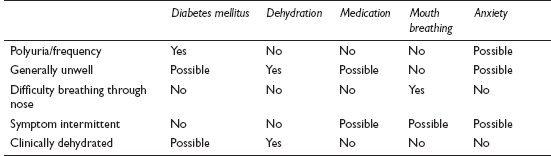

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

Usually none are necessary in practice. If a febrile child is ill enough to require investigation, the problem will usually be sufficiently urgent to need management by acute admission. Urinalysis, as a pointer to UTI (assuming obtaining a urine sample is feasible), is sometimes helpful in avoiding or facilitating admission. If possible, extend this to an MSU for bacteriological analysis.

TOP TIPS

Many clinical markers (see Ready reckoner) are non-specific and are present in many different infections. It is often a matter of degree as to how likely they are a pointer to a specific pathology. For example, many infections cause mesenteric adenitis with abdominal pain, but the tenderness of appendicitis, for example, is usually far greater on examination. Respiratory rate is raised in all fevers, but a chest problem will increase it further along with the presence of chest signs. A good policy is to be as thorough as possible in an examination so as to be able to cross-reference the maximum clinical information.

Many clinical markers (see Ready reckoner) are non-specific and are present in many different infections. It is often a matter of degree as to how likely they are a pointer to a specific pathology. For example, many infections cause mesenteric adenitis with abdominal pain, but the tenderness of appendicitis, for example, is usually far greater on examination. Respiratory rate is raised in all fevers, but a chest problem will increase it further along with the presence of chest signs. A good policy is to be as thorough as possible in an examination so as to be able to cross-reference the maximum clinical information.

Remember that parents will be worried about their child, and no matter how simple the management of this common problem appears to you, to the parent it may be the harbinger of a serious illness. Practise a calm and polite demeanour, empathy and sensitivity.

Remember that parents will be worried about their child, and no matter how simple the management of this common problem appears to you, to the parent it may be the harbinger of a serious illness. Practise a calm and polite demeanour, empathy and sensitivity.

In telephone advice calls, always do three things: first, check that the parent is satisfied with your advice; second, put a robust safety net/plan B in place with easily identifiable guidelines for the parent, e.g. ‘if by X hours Y has not happened, then call back’; third, record your clinical assessment and the last two points in detail.

In telephone advice calls, always do three things: first, check that the parent is satisfied with your advice; second, put a robust safety net/plan B in place with easily identifiable guidelines for the parent, e.g. ‘if by X hours Y has not happened, then call back’; third, record your clinical assessment and the last two points in detail.

If in doubt, always see a child in person. Be sensitive to your intuition. If something nags you after an advice call, ring back and arrange a consultation. You will never look stupid for doing this – only careful.

If in doubt, always see a child in person. Be sensitive to your intuition. If something nags you after an advice call, ring back and arrange a consultation. You will never look stupid for doing this – only careful.

Remember to follow up children in whom you’ve diagnosed UTI according to NICE guidelines, which recommend further investigation, varying according to the age of the child.

Remember to follow up children in whom you’ve diagnosed UTI according to NICE guidelines, which recommend further investigation, varying according to the age of the child.

It is very easy to print computerised clinical notes immediately after writing them. Handing a consultation note to a parent can be invaluable to the parent (and the clinician) if the child is seen later on out of hours, when clinical records are often unavailable. The baseline findings from earlier in the day can be priceless information in the dark hours later on.

It is very easy to print computerised clinical notes immediately after writing them. Handing a consultation note to a parent can be invaluable to the parent (and the clinician) if the child is seen later on out of hours, when clinical records are often unavailable. The baseline findings from earlier in the day can be priceless information in the dark hours later on.

Spend time explaining the nature of fever and that the key issue is the cause of the fever rather than the fever itself – many parents are ‘fever phobic’.

Spend time explaining the nature of fever and that the key issue is the cause of the fever rather than the fever itself – many parents are ‘fever phobic’.

It’s often more important to be able to distinguish between ‘well’ and ‘ill’ babies and children than it is to make a clever, precise diagnosis – the NICE ‘traffic light’ guidance may help.

It’s often more important to be able to distinguish between ‘well’ and ‘ill’ babies and children than it is to make a clever, precise diagnosis – the NICE ‘traffic light’ guidance may help.

It’s easy to be tempted into complacency in the telephone or consultation management of this problem – fever is just so common. Never forget that uncommon very serious illnesses may all begin with a fever. Always be diligent and systematic in assessment, no matter how busy your winter on-call day is turning out to be.

It’s easy to be tempted into complacency in the telephone or consultation management of this problem – fever is just so common. Never forget that uncommon very serious illnesses may all begin with a fever. Always be diligent and systematic in assessment, no matter how busy your winter on-call day is turning out to be.

Dehydration can kill a baby quickly. Ensure you have satisfied yourself about the state of hydration of a child. The colour and quantity of urine passed, or frequency of nappy changes are useful practical guides, together with the general ‘look’ of the child and the capillary refill time.

Dehydration can kill a baby quickly. Ensure you have satisfied yourself about the state of hydration of a child. The colour and quantity of urine passed, or frequency of nappy changes are useful practical guides, together with the general ‘look’ of the child and the capillary refill time.

A febrile baby or child who is floppy or drowsy should be admitted immediately.

A febrile baby or child who is floppy or drowsy should be admitted immediately.

Be suspicious of the irritable and inconsolable infant. Even without other hard evidence, suspect a serious problem and arrange urgent paediatric assessment.

Be suspicious of the irritable and inconsolable infant. Even without other hard evidence, suspect a serious problem and arrange urgent paediatric assessment.

The petechial rash of meningococcal septicaemia is a late phenomenon. Do not be reassured by its absence. Its presence should prompt a 999 call and administration of immediate parenteral antibiotics according to local protocols.

The petechial rash of meningococcal septicaemia is a late phenomenon. Do not be reassured by its absence. Its presence should prompt a 999 call and administration of immediate parenteral antibiotics according to local protocols.

In most cases, the height of a fever is no guide to the severity of the illness – the exception being babies, where a temperature of 38°C or more in those under 3 months is seen as a ‘red’ and one of 39°C or more in those between 3 and 6 months is viewed as ‘amber’ according to NICE.

In most cases, the height of a fever is no guide to the severity of the illness – the exception being babies, where a temperature of 38°C or more in those under 3 months is seen as a ‘red’ and one of 39°C or more in those between 3 and 6 months is viewed as ‘amber’ according to NICE.

FEELING TENSE AND ANXIOUS

![]()

The GP overview

The patient complaining of feeling tense and anxious may induce similar feelings in the GP – because there are many possible underlying and contributory causes, the consultation may be lengthy, and the patient may well present in a crisis. A calm, methodical approach, possibly stretching over more than one consultation, will pay dividends.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

life events (may be underlying ‘anxious personality’)

life events (may be underlying ‘anxious personality’)

pre-menstrual tension

pre-menstrual tension

generalised anxiety disorder

generalised anxiety disorder

panic disorder

panic disorder

depression

depression

OCCASIONAL

obsessive–compulsive disorder

obsessive–compulsive disorder

phobias

phobias

drug side effect (for example, in the early stages of SSRI treatment)

drug side effect (for example, in the early stages of SSRI treatment)

hyperthyroidism

hyperthyroidism

drug/alcohol use or withdrawal

drug/alcohol use or withdrawal

somatisation disorder

somatisation disorder

post-traumatic stress disorder

post-traumatic stress disorder

RARE

psychotic illness

psychotic illness

any cause of palpitations (may be ‘misinterpreted’ by the patient or others as anxiety)

any cause of palpitations (may be ‘misinterpreted’ by the patient or others as anxiety)

organic brain disease, e.g. tumour

organic brain disease, e.g. tumour

![]()

Ready reckoner

![]()

Possible investigations

It would be very unusual for the GP to require any investigations when dealing with this symptom. Thyroid function tests would be indicated in suspected hyperthyroidism, and a blood screen, to include LFT, if alcohol was thought to be playing a significant part. Investigations in the rare event of suspected organic brain disease would usually be left to the specialist.

TOP TIPS

It is tempting to lump many of these scenarios under a catch-all label of ‘tension’ or ‘anxiety’. But attempts at making a more precise diagnosis are worthwhile, as this may significantly alter the management.

It is tempting to lump many of these scenarios under a catch-all label of ‘tension’ or ‘anxiety’. But attempts at making a more precise diagnosis are worthwhile, as this may significantly alter the management.

Do not overlook an alcohol or drug history: abuse or withdrawal may be the cause of the symptoms, or a significant contributor.

Do not overlook an alcohol or drug history: abuse or withdrawal may be the cause of the symptoms, or a significant contributor.

It may be worthwhile carefully reviewing the patient’s old records to establish patterns of symptoms or attendance, and to check previous response to treatment.

It may be worthwhile carefully reviewing the patient’s old records to establish patterns of symptoms or attendance, and to check previous response to treatment.

Whenever possible, life events should not be ‘medicalised’ – otherwise this may, in the future, encourage re-attendance and foster dependence on treatment.

Whenever possible, life events should not be ‘medicalised’ – otherwise this may, in the future, encourage re-attendance and foster dependence on treatment.

Apparent pre-menstrual tension may be a sign of some other underlying disorder – the patient may be suffering generalised anxiety disorder, for example, but may tend to focus on the pre-menstrual phase, when the symptoms are at their worst.

Apparent pre-menstrual tension may be a sign of some other underlying disorder – the patient may be suffering generalised anxiety disorder, for example, but may tend to focus on the pre-menstrual phase, when the symptoms are at their worst.

Do not accept a self-diagnosis of ‘panic attacks’ at face value – the patient may actually mean any one of a number of possible symptoms.

Do not accept a self-diagnosis of ‘panic attacks’ at face value – the patient may actually mean any one of a number of possible symptoms.

If the underlying diagnosis turns out to be depression, assess for any suicidal ideas or intent.

If the underlying diagnosis turns out to be depression, assess for any suicidal ideas or intent.

Check for any psychotic features – anxiety can occasionally be a presenting feature of serious psychotic illness.

Check for any psychotic features – anxiety can occasionally be a presenting feature of serious psychotic illness.

New onset of tension or anxiety without any obvious explanation – especially in the context of personality change, neurological features or new headaches – could, rarely, reflect organic brain disease.

New onset of tension or anxiety without any obvious explanation – especially in the context of personality change, neurological features or new headaches – could, rarely, reflect organic brain disease.

It’s important to make diagnoses such as somatisation disorder when appropriate – otherwise the patient may suffer years of unnecessary tests and treatment.

It’s important to make diagnoses such as somatisation disorder when appropriate – otherwise the patient may suffer years of unnecessary tests and treatment.

FLUSHING

![]()

The GP overview

This symptom presents more often in women than in men, not only because of its cosmetic importance, but also because the menopause accounts for the vast majority of presentations. It is different from emotional blushing in its context, severity, duration and extent.

![]()

Differential diagnosis

COMMON

menopause

menopause

chronic alcohol misuse

chronic alcohol misuse

rosacea

rosacea

iatrogenic (e.g. calcium antagonists)

iatrogenic (e.g. calcium antagonists)

anxiety

anxiety

OCCASIONAL

polycythaemia rubra vera

polycythaemia rubra vera

hyperthyroidism

hyperthyroidism

drug/alcohol interaction: metronidazole, disulfiram

drug/alcohol interaction: metronidazole, disulfiram

mitral valve disease (malar flush)

mitral valve disease (malar flush)

hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia

hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia

epilepsy (aura)

epilepsy (aura)

RARE

carcinoid tumour

carcinoid tumour

phaeochromocytoma