Sir George MacMunn, The Religions and Hidden Cults of India (1932)

Rise up, O sons of India, arm yourselves with bombs, dispatch the white Asuras to Yama’s abode. Invoke the Mother Kali. . . . The Mother asks for sacrificial offerings. What does the Mother want? . . . A fowl or sheep or buffalo? No. She wants many white Asuras. The Mother is thirsting after the blood of the Feringhees. . . . [C]hant this verse while slaying the Feringhee white goat: with the close of a long era, the Feringhee Empire draws to an end, for behold! Kali rises in the East.

Jugantar, Bengali newspaper (1905)

Imagined as the most radical, dangerous, and transgressive of spiritual paths, in explicit violation of accepted ethical boundaries, Tantra was soon to be associated in both the Western and Indian imaginations with the possibility of political violence. If Orientalist authors began to shift from “Indophilia” to a more critical “Indophobia” in the years after 1833, this suspicious attitude was even more pronounced in the years following 1857, during the “crisis of the raj” in the wake of the Indian Mutiny. And it reached its peak in the tumultuous years of the early twentieth century, in the face of a growing, often violent nationalist movement whose struggle for independence was sometimes bloody.1 Throughout the late nineteenth century, Tantra was increasingly identified with the most dangerous subversive movements, such as the criminal Thuggee and the political extremists of the nationalist movement. “Tantrism acquired a new political dimension as British fears about civil unrest and mutiny were excited and linked to the supposed degeneracy of the natives.”2 However, to use Taussig’s terms, we might say that the colonial paranoia about Tantric savagery was as much a projection of the “barbarity of their own social relations” as it was a reflection of any actual Indian reality: “The magic of mimesis lies in the transformation wrought on reality by rendering its image. . . . In the colonial mode of production of reality. . . such mimesis occurs by a colonial mirroring of otherness that reflects back on the colonists the barbarity of their own social relations, but as imputed to the savagery they yearn to colonize.”3

For Indian authors of the nineteenth century, conversely, the attitude toward the radical practices of Tantra was more complex and ambivalent. For the reformers and the more conservative members of the nationalist movement, Tantra was typically seen as a terrible embarrassment, a major reason for India’s backwardness and lack of political power, one of the things most in need of eradication on the road to self-governance. Yet, remarkably, for the more radical, extremist wing of the nationalist movement, Tantric forms and symbols could also be used positively, as a source of revolutionary inspiration. Many Indian authors, such as the young Aurobindo Ghose, would appropriate and exploit the terrifying image of Tantra, and particularly the violent goddess Kālī, as the most powerful embodiment of their political cause. As a powerful dialectical category, Tantra could not only be employed by colonial authors as proof of Indian backwardness, barbarism, and savagery; it could also be turned around and redeployed as the symbol of India in violent revolt against her colonial masters.

In this chapter, I will explore, first, the paranoid fears of Tantric secrecy and violence that emerged in the colonial imagination, as we see in British descriptions of the goddess Kālī and the criminal gangs of the Thuggee. I will then examine the ways in which some Indian authors in turn appropriated the images of Kālī and Tantra as revolutionary weapons, exploiting their terrifying power in the colonial imagination. As we will see in the case of complex figures like Aurobindo, the Goddess could symbolize both Mother India, in violent rebellion against her colonial oppressors, and the Divine Mother, seeking some kind of harmony with the West in an age of postcolonial compromise.

It is just this presence of some ancient horror, existing beneath the surface of perfectly reasonable political aspirations, which has been a source of trouble to many a kind Viceroy desiring only India’s good.

Sir George MacMunn, The Underworld of India (1933)

Based in large part on the descriptions of Orientalist scholarship, British government officials and colonial administrators also began to take an interest in the tantras and to contribute a new element to the imagining of Tantra. For the most part, Tantra was an object intense anxiety for the colonial authorities, who suspected it of revolutionary agitation and subversive plots. Throughout the European colonial imagination of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the fear of subversive political activities often went hand-in-hand with the fear of immoral practices among the natives under their rule. As we see in the cases of the Mau Mau in Kenya or in various native uprisings in South America, political rebellion was often believed to be associated with immorality, sexual transgression, and the violation of social taboos. The rebellious colonial subject threatened not only to subvert colonial rule, but to unravel the moral fabric of society itself. As Nicholas Thomas observes, “Colonial rule was haunted by a sense of insecurity,” terrified by the “obscurity of the native mentality” and overwhelmed by the indigenous societies’ “intractability in the face of government.”4 Perhaps this was true nowhere more than in colonial India of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Above all, India was imagined as a land where political activism and religious fervor were often wedded in the most dangerous form. In the insidious “Indian underworld,” as M. Paul Dare described it, “crime, religious belief and magic are entangled . . . to a degree inconceivable to the western mind.”5 As Richard King suggests, the West has long held two powerful images of Indian religions: on one side, the detached, transcendent otherworldly mystic, and on the other, the “militant fanatic,” the crazed devotee of mindless religion.6 This association between political violence and religious extremism became increasingly acute after May 1857, the pivotal moment of the Indian Mutiny, when the Bengal Army revolted against its British officers, sparking a widespread violent bloodbath. Allegedly caused by specific religious reasons—the use of beef fat in gun cartridges—the mutiny probably had behind it a host of other cultural causes—such as Christian missionary activity, the prohibition of religious practices, and the introduction of Western education. Culminating in the Kanpur Massacre, with the grisly murder of British women and children prisoners, the mutiny became for the British authorities the epitome of all the “cruelty and impulsiveness” of their subjects and so the justification for the “moral and racial condemnation of native Indians.”7

Tantra would come to represent the epitome of this dangerous fusion of religion with political action, a kind of perverse mysticism combining not just religion and sensuality, but criminal behavior and political unrest. As Valentine Chirol warned in Indian Unrest, there was an intimate connection between the sexual license of the Tantric secret societies and the subversive acts of the revolutionary political groups: “The Shakti cultus, with its obscene and horrible rites . . . represents a form of erotomania which is certainly much more common among Hindu political fanatics.”8 Above all, this erotomaniac fanaticism seemed to have reached its most extreme form in the violently sexual figure of the Tantric goddess.

Kālī is wholly given over to cruelty and blood. She drinks the blood of her victims. She lives in an orgy of horrors.

Rev. E. Osborn Martin, The Gods of India (1913)

To know the Hindoo idolatry as it is, a person must wade through the filth of the thirty-six pooranus. . . . [H]e must follow the brahmun through his midnight orgies before the image of Kalee.

William Ward, A View of the History, Literature, and Religion of the Hindoos (1817)

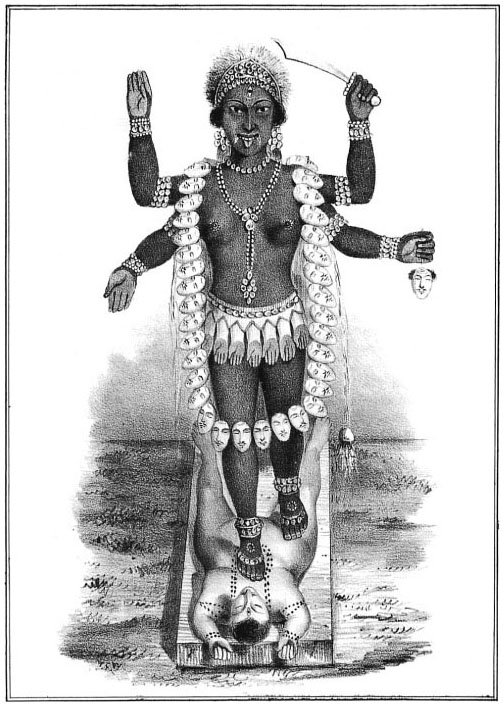

Throughout the British and European literature of the colonial era, few figures held such a central role, as a source of mixed horror and fascination, as did the Tantric goddess Kālī (see figures 5 and 6). As Friedrich Max Müller put it, “nothing is so hideous as the popular worship of Kālī in India.”9 The goddess of time, darkness, and death (kāla), Kālī has been a powerful presence in the Hindu religious imagination since at least the early centuries of the common era. The first known account of Kālī as a wild, bloodthirsty goddess appears in the Mahābhārata, during Aśvatthāman’s night attack on the Pāṇḍavas (10.8.64). In the Purāṇas, Kālī emerges as a goddess of battle and war, often associated with lower-class people and non-Aryan tribals. However, her most famous appearance is found in the Devī-Māhātmya, a portion of the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa, where she emerges as the wrathful projection of Durgā, a hideous, bloodthirsty creature, raging about the field of battle and slaying demons.10 A goddess of military power and death, she is also the goddess of time itself, associated with destruction on a universal scale, the eschatological dissolution of the world at the end of the age. Portrayed as a “frightening hag with disheveled hair, pendulous breasts and a garland of skulls,” she is “the embodiment of the fury which can be raised in the divinity under emergency conditions.”11

Figure 5. “Procession of the Hindoo Goddess Kali.” From Colin Campbell, Narrative of the Indian Revolt: From Its Outbreak to the Capture of Lucknow (London: G. Vickers, 1858).

Not surprisingly, given her extreme role in the Indian tradition, Kālī soon assumed an even more terrifying role in the colonial imagination. As Ward describes her, Kālī is the very epitome of that “puerile, impure and bloody system of idolatry” that is the Hindu faith. With her horrific violence and rampant sexuality, Kālī is the most explicit embodiment of this ghastly perversion that passes under the name of religion:

The dark image of this goddess is a truly horrid figure. . . . [S]he holds in one hand a scimitar in another a giant skull. . . . [S]he stands upon her husband . . . to keep him in subjection till the time of the universal conflagration. . . . She exhibits the appearance of drunken frantic fury. Yet this is the goddess . . . upon whose altars thousands of victims annually bleed, and whose temple . . . is the resort of Hindoos from all parts of India.12

Figure 6. Mahā Kālī. From Charles Coleman, The Mythology of the Hindoos (London: Parbury, Allen, 1832).

A similar, perhaps even more colorful, account is that of the Scottish missionary Alexander Duff, who describes Kālī’s worship as a kind of Satanic delirium comprised of mindless violence and bloodshed: “Of all Hindu divinities, this goddess is the most cruel and vengeful. . . . The supreme delight of this divinity. . . consists in cruelty and torture; her ambrosia is the flesh of sacrificed victims; and her sweetest nectar, the copious effusion of blood.”13

Throughout the accounts of British authors of the colonial era, the image of Kālī represents a kind of impenetrable, almost inconceivable mystery—a source of simultaneous horror and fascination, which the Western mind cannot fathom but which it feels compelled to describe in endless, almost obsessive detail. She is a “form to be remembered for its grotesqueness and startling ugliness,” and “a hideous black woman . . . with a huge blood-red tongue hanging out of her mouth.”14 As such, she represents the most primitive substratum of the Indian mind itself:

No one can tell in what age it was that divinity revealed itself to the vision of some aboriginal . . . seer in the grotesque form of Mother Kali, nor does any record exist regarding the audacious hand that first modelled . . . those awful features . . . crudely embodying . . . the very dread of femininity always working in the minds of a most sensuous people, too prone to fall before the subtle powers of the weaker sex. . . . [T]he strange shapes of Kali . . . date back to primeval times, and may be regarded as only the fantastic shadows of divinity seen . . . in the dim twilight of world’s morning.15

Above all, the figure of Kālī and the secret rites of her Tantric devotees were regarded as manifestations of the fanatical side of the Indian mind and thus as a dangerous source of unrest: “This divinity is the avowed patroness of all the most atrocious outrages against the peace of society.”16 As Chirol observes in Indian Unrest, the worship of Kālī represents the worst example of the manipulation of religious superstition in the service of political agitation: “The constant invocation of the ‘terrible goddess’ . . . against the alien oppressors, shows that Brahminism . . . is ready to appeal to the grossest and most cruel superstitions of the masses.”17 Here, we see a kind of paranoia similar to that found in other situations of colonial domination. As Taussig observes in the case of colonial South America, the fear of native rebellion created all sorts of nightmarish fantasies of cannibals, head hunters, and shamans threatening to rise up against law and order: “The uncertainty surrounding the possibility of Indian treachery fed a colonially paranoid mythology in which dismemberment, cannibalism . . . body parts and skulls grinned wickedly.”18

Intense devotion to Kalee is the mysterious link that unites them in a bond of brotherhood that is indissoluble; and with secrecy which for generations has eluded the efforts of successive governments to detect them.

Rev. Alexander Duff, India and Indian Missions (1839)

In a growing body of nineteenth-century literature, both factual and fictional, the figure of Kālī and her Tantric devotees began to be associated with criminal activity and the notorious gangs of robbers (dacoits) believed to thrive in the underworld of India. “Thieves pay their devotion to Kalee . . . to whom bloody sacrifices are offered under the hope of carrying on their villainous designs with success.”19 The most infamous of these groups, and the most sinister in the British imagination, were the gangs known as the Phansigars (“stranglers”) or more widely as the Thuggee (“deceivers”). To what degree the Thuggee were a real organization or, rather, the fabrication of British imagination and colonial paranoia is difficult to say.20 As Cynthia Humes has argued, the British authorities of the early nineteenth century initially regarded the Thuggee as clear evidence of the dangerous criminal elements within the subcontinent—and thus as a justification for the need of extensive British rule and the strict imposition of colonial law. Yet increasingly in the nineteenth century, and above all after the mutiny of 1857, the threat of the Thuggee began to intensify within in the colonial imagination, growing into a sinister nationwide organization, dedicated to the subversion of British colonial rule.21

The legends of the Thuggee first appeared when Dr. Richard Sherwood published a report on the Phansigars in the Madras Literary Gazette in 1816. According to Sherwood’s account, which would later become one of the most widely read versions in the colonial era, the Phansigars were both a criminal and a religious sect, patronized by the local rulers who gave it protection and shared its profits. They were, in short, “villains as subtle, rapacious and cruel as any who are to be met with in the records of human depravity.” Being “skilled in the arts of deception,” the Phansigars would first send ahead scouts in order to identify wealthy travelers on the roads, and then pose in the guise of fellow travelers, walking alongside the targeted party and gaining their trust.22 Having deceived their intended victims, the Phansigars would then suddenly break that trust by strangling their victims from behind, using their trademark handkerchief or scarf.

However, the Thuggee became infamous as a criminal organization only due to the efforts of Colonel William Sleeman, later renowned as “Thuggee Sleeman.” Born to a respected Cornish family in a long line of soldiers, Sleeman arrived in India in 1809 and served in Nepal from 1814 to 1816. In 1818, Sleeman grew curious about these notorious gangs of murderous robbers and requested to be transferred to the civil service in order to investigate the Thuggee full-time. Soon Sleeman concluded that the Thuggee were far more than a small band of petty criminals, but were in fact a nationwide organization—“a numerous and highly organized fraternity operating in all parts of India.”23 “He believed that India was under attack—that the foundation of human society was in danger of being destroyed. . . . He recognized Thuggee as instruments of the ultimate evil in their day, of that which as an end in itself takes human life indiscriminately. He was inspired by the belief that Thuggee must be destroyed.”24

The most intensive period of the Thuggee investigation began in 1831–32, as Sleeman and his men gradually widened their circle from their initial forays in Bundelkand and western Malwa to spread throughout the subcontinent: “From the foot of the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, from Cutch to Assam, there was hardly a province . . . where Thuggee had not been practiced.”25 In short, as Amal Chatterjee observes, “Thugs, once ‘discovered’ sprang up all across India. . . . [S]o convinced were the propagators of the fiction that it began to be recorded everywhere,” as every petty criminal from highway thief to river pirate was identified with the “Thuggee menace.”26 Sleeman had meanwhile gathered a vast body of reports, rumors, and confessions regarding the activities of this group, eventually publishing them in Ramaseeana; or, A Vocabulary of the Peculiar Language Used by the Thugs. The most famous of these accounts is the confession of the leader known as Feringhea, “the prince of thugs,” who reportedly unveiled the secrets of the cult, which were “so incredible that at first Sleeman would not believe them.”27 In Sleeman’s eyes, this cult represented an ancient evil in the heart of India, possibly going as far back as the Tartar and Mogul tribes, and surviving secretly for centuries as the terrifying underbelly of India.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the Thug was precisely his dissimulating, duplicitous character—that he was first and foremost a deceiver. While appearing to be a good citizen and loyal subject of British law, the Thug was in fact a murderous criminal of the most sinister type:

The most astounding fact about the Thug is that . . . he was a good citizen and model husband devoted to his family and scrupulously straight when not on his expeditions, presenting a complexity of character utterly baffling to a student of psychology. It was essential to the safety of their criminal operations that they should pass as peaceful citizens. . . . Not only had they left no trace behind of their foul deed, but they concealed their trail by every art and craft, and with ill-gotten rupees bribed officials, police and villagers, in whose territory the murders had occurred. . . . It is not extraordinary that Thuggee remained a mystery; rather it is remarkable that it was ever brought to light.28

Thus, if it is true, as Homi Bhabha suggests, that “colonial power produces the colonized as a fixed reality which is at once an other and yet entirely knowable and visible,”29 then the Thug is a threat precisely because he is both unknowable and invisible. He is a deceiver who defies the all-penetrating gaze of colonial rule.

Whether the Thuggee were a real or an imaginary cult, a rich lore quickly grew up around them, combining fact and fantasy into a vivid narrative. Through the combined influence of Sleeman’s personal accounts, the vivid chronicles of Thuggee persecution by Sir Edward Thornton (1837), and the popular fictional account by Philip Meadows Taylor (1839), a kind of Thuggee mythology had emerged, much of it centering on the figure of Kālī and her Tantric cult.30 Under the form of Bhowani, it was believed, Kālī was worshiped by the Thuggee before they went out on their sprees of killing and banditry. According to the now infamous Thuggee legend, Kālī had come in the form of Bhowani in order to kill the demon Rukt Bij-dana. Although Kālī cut the demon in two, every drop of his blood that fell to earth gave birth to new demons; therefore the goddess created two men from the sweat of her arms and commanded them to strangle the demons using a rumal, or handkerchief. Kālī then established the cult of Thuggee, dedicated to her, which would continue the ritual art of strangulation and robbery. Initially, the story goes, Kālī had agreed to devour the corpses herself; however, after one of her devotees looked back to watch her as she consumed a victim, she refused to eat the bodies any longer. Instead she gave the Thuggee a sacred pickax with which to bury the corpses.

Not only were they thought to engage in rampant violence in the name of Kālī, but the Thuggee were also believed to hold dark secret rituals dedicated to her. These sinister rites were described as a kind of Black Mass, consisting of blood sacrifice and sacramental consumption of wine and meat. (While reading these accounts, it is difficult for a modern reader not to be reminded of medieval Inquisitors’ accounts of witchcraft, or the Christian Fathers’ accounts of the perverse rituals of certain Gnostic heresies):

A silver or brazen image of the goddess . . . together with the implements of Phansigari, such as a noose, knife and pick axe, being placed together, flowers were scattered over them and offerings of fruit, cakes, spirits, &c. are made. . . . The head of the sheep being cut off, it is placed with a burning lamp upon it . . . before the image . . . and the goddess is entreated to reveal to them whether she approves of the expedition.31

A ritual feast . . . took place after every murder, sometimes upon the grave of the victim. The goor or coarse sugar took the place of the Christian communion bread and wine.32

In sum, in the eyes of many British officials, the Thuggee and their demonic patroness, Kālī, came to represent the most extreme example of the natural tendency toward lawlessness, perversion, and murderous instinct lying at the darkest heart of the Indian race:

The dark night of superstition, which has long clouded the moral vision of India, has given rise to practices so horrible that without the most convincing evidence, their existence could not be credited. . . . That giant power which has held the human race in chains wherever the . . . doctrines of revelation have not penetrated, has in India reveled in prosperity. . . . Here the genius of paganism had reared a class of men who are assassins by profession, called Phansigars or Thugs.33

Thus, with their sinister skills in deception, their ties to indigenous political corruption, and their devotion to the cruel goddess Kālī, the Thuggee seemed to provide the clearest evidence of the need for British rule in the subcontinent. “These common enemies of mankind, under the sanction of religious rites, have made every road between the Jumna and Indus rivers . . . a dreadful scene of lonely murder,” Sleeman lamented, concluding that “we must have more efficient police establishments along the high roads . . . to root out entirely this growing evil which has been . . . increasing under the sanction of religious rites.”34

The India that the British found in the late eighteenth century seemed to them a land sunk in immorality and decay, destroying itself with criminal gangs who preyed upon its own citizens, and woefully misruled by self-serving rājas. According to most colonial narratives, India suffered a profound social breakdown following the collapse of the Mughal empire; the officers of the East India Company found India “ravaged and exhausted,” strewn with “sacked palaces, vanishing roads, toppled fortresses . . . and ruined towns.”35 As Sir John Malcolm comments, the widespread presence of the Thuggee was the most acute example of this general state of moral and political decay: “the native states were disorganized and society on the verge of dissolution; the people crushed by despots, the country overrun by bandits. . . . [G]overnment had ceased to exist; there remained only oppression and misery.”36 At the same time, the Thuggee cult also revealed the political corruption that was rampant throughout India. Protected by the local rulers whom they bribed, the Thuggee were able to survive due to the greed of the petty kings and a hypocritical legal system: “In an Eastern court of those days, bribery almost always took the place of justice and this, combined with fear, was responsible . . . for the extreme leniency shown.”37

Given a political system so corrupt, Agent to the Governor-General F. C. Smith argued, the Thuggee should never be entrusted to the indigenous authorities. Instead, they should be tried by the more competent and efficient authority of the British government: “the feeble efforts of the native Chiefs having totally failed to suppress them, no Thug should . . . be made over to a native Chieftain for punishment, experience having shown their utter incapacity to put them down and expose their corrupt practices of concealing Thugs for valuable considerations.”38 The suppression of the Thuggee therefore demanded not only the assertion of British authority over that of local rulers, but also the formation of new special courts and the spread of British legal structures over the whole of India: “Nothing but a general system, undertaken by a paramount power, strong enough to bear down all opposition by interested native chiefs, could ever eradicate such well-organized villainy.”39 Perhaps the most important of the new legal structures was Act 30 of 1836. Extending Company jurisdiction to territories outside its actual dominions, the act allowed the offense in question to be tried in any Company court; it allowed trials to be conducted without any form of Islamic law; and it allowed conviction on the sole basis of membership in a gang of Thuggee. Hence this new system provided the ideal legitimation for the persecution of the “Thug menace.” For even if there was often little evidence against the alleged Thuggee cult that would hold up in a regular court of law, now the British officials had a new license to receive and use evidence however they saw fit.

Ultimately, it was believed to be due in large part to the British suppression of Thuggee that the indigenous Indian population finally learned to respect the just authority of its colonial rulers. For the British had apparently been able to contain and control a disease that had been ravaging India for hundreds of years: “Those were the days when British rule in the East was synonymous with courage, strength and justice. . . . [T]he Indian had faith in British government and learned to respect it.”40 In sum, the heroic work of Sleeman and his men to suppress the Thuggee menace was regarded as the most “fitting monument to British rule.” Just as benign British rule had saved India from its own moral decay and political chaos, so the selfless labors of Sleeman had saved India from a disease that had rotted the country from within.

If the only monument to British rule in India was the suppression of Thuggee, it is doubtful whether any other nation could show a finer one. For . . . the Englishmen themselves suffered no harmful effects from this malignant enterprise and therefore no selfish motive prompted those who were responsible for suppressing this secret . . . system of murder. What other men of any other Western nation have deliberately imperiled their lives for years on end to protect native life only?41

By the late nineteenth century, however, the Thuggee myth had begun to assume a much darker and more threatening form. If the early narratives used the Thuggee as an example of India’s lawlessness and the need for strong British rule, the later narratives reveal a fear that the Thuggee had grown into something far more dangerous than a mere underground criminal group. Particularly in the decades after the mutiny, the Thuggee myth grew into a full-blown paranoid fantasy, now imagined as a nationwide political organization, fueled by religious fanaticism, and dedicated to the overthrow of British rule itself. As MacMunn concludes,

Thuggism was rampant all over India, from the Himalaya to the edge of Ceylon, and east and west from Cutch on the Indian Ocean to Assam on the Burma border. . . .

For many years the Department of Thuggee . . . kept watch on this movement lest it should show its head again, and also on various secret movements, subversive of both civilization and the British Raj. Eventually it was merged in the Criminal Intelligence Department, whose annals will make the most astounding reading in the world, in which crime mingles with Shiva and Vishnu in a manner unknown elsewhere.42

Thus it is not surprising that this criminal menace would soon be linked to more overt political agitation, as well.

In its extreme forms Shakti worship finds expression in licentious aberrations which . . . represent the most extravagant forms of delirious mysticism.

Valentine Chirol, Indian Unrest (1910)

The fear of the subversive power of Tantra would reach its height of intensity in the early twentieth century, with the rise of overt political resistance, particularly in hotbed regions like Bengal. Beginning with the Swadeshi (swadeshi, “of our own country”) movement, which burst into violent agitation after the partition of Bengal in 1905, the nationalist revolutionaries appeared to the British government to represent a dangerous combination of religion and politics (a confusion almost as dangerous as the perverse mingling of sex and religion). For “in India, indeed, religion enters into politics as it does into most of the activities of man which in the West are usually described as secular.”43

This monstrous fusion of religious fanaticism and subversive activities had reached its terrifying fruition in the revolutionary nationalist groups of the twentieth century. As the Rowlatt Commission of 1918 reported, the revolutionary outrages in Bengal were “the outcome of a widespread movement of perverted religion and equally perverted patriotism.”44 Calling upon the terrible mother Kālī for power, worshiping her with orgiastic violence, and even “sacrificing the white goats” of British officials to the goddess, they threatened the moral and political fabric of the colonial state itself. In many accounts, the nationalist movement is described as nothing less than a pervasive secret organization combining mysticism and political subversion—an “underground murder cult” comprised of a “strange melange of masonic ritual and a festival of horrible furious Kali in her wilder aspects.”45

All of this was only natural, however, since the “Indian mind” was believed to have an inherent tendency toward the fusion of sexual license and political violence. The revolutionaries exploited this natural proclivity toward eroticism and criminality, inciting the sexually volatile young men to vent their frustrations at the British: “The Hindu student, depraved . . . by too early eroticism, turns to the suggestiveness of the murder-monger and worships the nitro-glycerine bomb as the apotheosis of his goddess.”46 Many authors attributed the prevalence of revolutionary activity among Bengali students to the overstimulating sexual practices of this culture—specifically the exposure of men to “early eroticisms” and young marriage, which is “terribly reflected in its effect on erotic young students . . . with their erotic hothouse nature.”

One of the most pitiful of all the manifestations of unrest . . . is the strange underground movement . . . which has produced a secret bomb and revolver cult, an assassination society with secret initiation. . . . Behind all the cruelty and sudden death of the world lies . . . Kali, the goddess of all horror. . . . “I am hungry” is her cry. “I want blood, blood victims.” . . . Not even the perverted imaginations of the Marquis de Sade could devise a more horrible nightmare than Kali. . . . To minds such as students . . . overstrained by premature eroticism . . . this deity becomes a cult in which half-mystical murder may be a dominant thought.47

Here are conflated in the colonial imagination all the worst aspects of Tantra. Moral corruption, religious perversion, and political unrest come together around the image of Kālī and her obscene devotion. In the colonial imagination, Tantra is not just an example of the “savagery they yearn to colonize,” but the presence of a savagery that cannot be colonized, an irrational, violent, and sexual power that threatens to consume the white masters.

On the day on which the Mother is worshipped in every village, on that day the people of India will be inspired with a divine spirit and the crown of independence will fall into their hands.

Jugantar (1905)

Just when [human beings] seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves . . . in creating something that never existed before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they conjure up spirits of the past and borrow from them names, battle slogans and costumes in order to present the new scene of the world in this time-honored disguise. . . . Thus Luther wore the mask of the Apostle Paul, the revolution of 1789 . . . draped itself alternately as the Roman Republic and Roman Empire.

Karl Marx, Die Revolution (1852)

As in every case of colonial domination, the Indians were by no means content to remain passive and unreflective, merely accepting the imaginary representations imposed upon them by colonial authorities. On the contrary, like native peoples in all situations of colonial contact, they had the potential to engage in a variety of “strategies of appropriation and subversion,” often by “taking over colonial sources and turning them to anti-colonial uses.”48 They too had the ability to engage in a fierce war of images, often by manipulating the figure of Kālī and transforming her into a source of anticolonial struggle.

Borrowing Benjamin’s phrase, we could say that Kālī is an ideal example of a dialectical image—a crystallized fusion of past and present, ancient religious myth and contemporary politics. Every community, Benjamin suggests, has a kind of “cultural memory” or a “reservoir of myths and utopian symbols from a more distant Ur-past.”49 These collective images can be used by established institutions to legitimate existing ideologies and political hierarchies; but they can also be used by oppressed classes as a source of political awakening. In the form of the dialectical image, mythic narratives of past traditions, utopian visions, and nostalgic longings for lost paradise can be seized upon, “reanimated,” and transformed into revolutionary visions of liberation.

Paradoxically, collective imagination mobilizes its powers for a revolutionary break from the past by evoking a cultural memory reservoir of myths and utopian symbols from a more distant Ur-past. . . . Utopian imagination thus cuts across the continuum of . . . historical development as the possibility of revolutionary rupture.

[The] shock of this recognition [can] jolt the dreaming collective into a political awakening. The presentation of the historical object within a charged force field of past and present, which produces political electricity . . . is the dialectical image.50

It is in precisely this sense, I will argue, that the terrifying figure of the Tantric goddess Kālī was seized by the radical nationalist movement as an image of revolutionary awakening.

During the colonial era, the image of Kālī thus became the focus of a complex play of representation and misrepresentation, a play of mimesis, in Benjamin’s and Taussig’s sense of the term. As the basic human faculty for grasping the foreign or the unknown, mimesis is our ability to represent the Other.51 Within the colonial imagination, the native is often represented as the negative antitype of the colonizer: conceived as savage or feminine, the native embodies the irrationality and backwardness against which the colonizer imagines himself. Yet particularly in cases like the terrifying goddess Kālī, this image often becomes a frightening mirror that reflects back the colonizers’ own deepest fears, fantasies, and dangerous desires.

At the same time, of course, colonized peoples also have their own powers of mimesis and their own ways of imaginally representing the colonizing Other. In some cases, this takes the form of a playful mimicry or parody that mocks the colonial ruler; in other cases, it assumes a more subversive form, as the colonized subject appropriates the representations of the colonizers themselves, often inverting them as counterhegemonic weapons of resistance. For example, Taussig points to the construction of the image of the “shaman” in colonial South America. As a powerful dialectical image, the shaman was in large part the result of a complex play of mimesis between the Europeans and the colonized Indians. If the colonial rulers had imagined the Indian to be an inherently savage and mysterious creature—a wild man and dangerous sorcerer, with threatening magical powers—then the Indians could likewise seize upon that image. Thus they embraced and exploited it, transforming the image into the dialectical image of the shaman, a figure embodying the power of wildness and supernatural danger, so threatening to the white man: “the shaman tames savagery, not to eliminate it, but to acquire it.”52 Hence, the image of the shaman demonstrates the ever threatening power of the oppressed over the oppressor, of the colonized over the colonizer.

An even more striking example that Taussig cites is the common eighteenth-century European representation of America as a woman, typically a beautiful naked woman adorned with feathered headdress, bow, and arrows. This New World/Woman, however, could assume both benevolent and terrifying features, imagined either as an inviting maiden awaiting the European colonizers, “languidly entertaining Discoverers from her hammock,” or as a horrifying demoness, “striding brazenly across the New World as castrator with her victim’s bloody head in her grasp.”53 Yet, as Taussig points out, the image of America as female was not only used by the European colonizers, but it was also reappropriated by the Indians, who transformed it into a symbol of Indianness, an anti-European, revolutionary spirit (for example, in Pedro Jose Figuero’s famous painting of Bolivia as a woman wearing a feathered headdress, seated next to the liberator of the nation, Simon Bolivar [1819]).

Nationalism is an avatār that cannot be slain. Nationalism is a divinely appointed Śakti of the Eternal and must do its God-given work before it returns to the bosom of Universal Energy from which it came.

Sri Aurobindo, quoted in Iyengar, Sri Aurobindo (1950)

We find much the same dialectical play of imagery in the role of Kālī in colonial Bengal. Above all, in the Bengal nationalist movement, the violent image of Kālī was transformed into the supreme symbol of Mother India fighting violently against her foreign oppressors. The origins of the Bengal nationalist movement lie in the more moderate ideals of the Indian National Congress of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, led by more conservative figures like R. C. Dutt or G. K. Gokhale. However, its second and most volatile period began in 1904, with the Swadeshi movement’s more direct challenge to the legitimacy of British rule. Finally, in 1905, it burst into open conflagration with the British partition of West Bengal (with Bihar and Orissa) from East Bengal and Assam. In the period after 1907, the Swadeshi movement began to assume a more violent and extremist form, abandoning the earlier doctrines of passive resistance or boycott in favor of the tactics of revolutionary terrorism.54

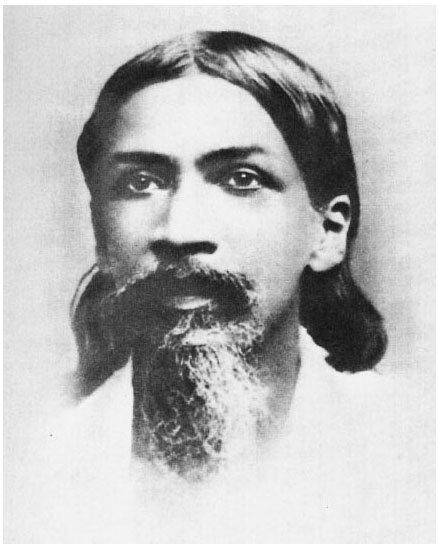

Figure 7. Sri Aurobindo as a young man. Frontispiece to Haridas Choudhuri, Sri Aurobindo and the Life Divine (San Francisco: Cultural Integration Fellowship, 1973).

One of the most outspoken members of the revolutionary strain of the movement was Aurobindo Ghose (figure 7), a man who in his later years would renounce the political life in order to pursue the spiritual path, eventually becoming one of the greatest religious leaders of modern India. Born in India but educated in England, Aurobindo returned to his homeland in 1893 to work for the State Service in Baroda. With the partition of Bengal in 1905, however, Aurobindo decided to leap headlong into the political maelstrom of Bengal. Leaving his position in Baroda, he arrived in Calcutta at the very height of the Swadeshi movement. The ideal that Aurobindo came to adopt was that of swaraj, or complete autonomy for India, which could only be achieved by a radical overthrow of British power. Although he is credited as one of the first advocates of passive resistance, Aurobindo also did not hesitate to promote armed resistance. In a just cause, “all methods were permissible”; therefore, “he shrewdly kept in reserve the weapon of secret revolutionary activity to be brought into the open . . . when all else failed.”55 As Aurobindo later wrote of his own involvement in the national movement, “my action in giving the movement . . . its militant turn or forming the revolutionary movement is very little known.”56

The primary medium for Bengal’s early revolutionary activities was a network of secret societies and underground movements. Calcutta, Dhaka, and other cities were filled with a host of secret organizations, both religious and political, working on the margins of and often in violent opposition to the existing social and governmental structures. Decades earlier, Aurobindo’s grandfather Rajnarain Bose had organized a secret society, of which Rabindranath Tagore had been a member, dedicated to revolutionary action. The two most prominent of these secret groups were the Anushilan Samiti—which was originally founded by Aurobindo and others in 1902—and a looser group later known as Jugantar (the New Age).57 As Aurobindo put it in a letter of 1911, his aim was to instigate “a secret revolutionary propaganda and organization.”58 Although Aurobindo would later deny his involvement with the radical actions of the Jugantar group, his brother Barindra and other members clearly regarded him as its founder, chief inspiration, and karta, or boss.

Throughout these organizations, there were often deep connections between Śākta Tantra and revolutionary politics. Much of the impetus for the secret groups came from the well-known novel of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Ānandamaṭh—the story of a group of revolutionary sannyāsīs (renunciants, ascetics) and devotees of the Mother Goddess who hope to overthrow Muslim rule in Bengal. Inspired by Bankim’s work, Aurobindo and others deployed a network of secret organizations in order to work behind the scenes toward an armed revolution. As Kees Bolle, Leonard Gordon, and others have observed, the revolutionaries explicitly appropriated many structures of Śākta Tantra, adapting “neo-Tantric rituals” and initiations to the service of building up an underground revolutionary organization. “Śākta religious rituals played a significant role in cementing unity and discipline. . . . The left wing extremists which organized themselves into revolutionary secret societies followed the practice of taking vows before the goddess Kālī.”59 Peter Heehs summarizes the initiatory oath, as recorded by the Government of India Home Department:

The Sanskrit oath, probably written by Aurobindo, took the form of a Vedic sacrificial hymn. Invoking Varuna, Agni and other deities . . . bowing down to the ideal heroes of India that sacrificed their lives to save the motherland . . . the oath-takers poured their hatred and shame into the fire . . . to save the country. Renouncing all life’s pleasures, they vowed to dedicate themselves to the establishment of the Dharma Rajya [Righteous Kingdom]. . . . Then bowing to a sword, crown of all weapons, the symbol of death, they lifted it up in the name of the Adya Shakti (original Energy, conceived as the Goddess Kālī).60

The public voice of the movement was communicated through the Calcutta newspapers Bandemataram, to which Aurobindo was a regular contributor, and the more radical Jugantar, begun by Aurobindo’s brother, Barin. The latter openly preached revolution and subversion of British authority. Calling the Bengali youth to give themselves in “sacrificial death” to the nationalist cause, the newspaper gave precise directions as to how one should start a secret terrorist organization and carry out terrorist activities.61 Not surprisingly, Jugantar was prosecuted for sedition six times before its final suppression in 1908.

Under Barin’s direction, the revolutionaries worked underground, collecting arms and making bombs. Although Aurobindo did not carry out terrorists acts himself, it seems probable that he both knew of and helped guide the group’s terrorist activities. What Aurobindo sought was not random terrorism, but “a full-scale insurrection,” hoping that “successful revolutionary acts might create popular interest and at the same time intimidate the enemy.”62 Thus, a laboratory was built at the Bengal Engineering College in order to make bombs; and on April 30, 1908, members of the society at Muzaffarpur threw a bomb intended for Douglas Kingsford, who was just transferred from his post as chief presidency magistrate at Calcutta. Tragically, however, the bomb instead hit the carriage bearing Kingsford’s daughter.

Despite his violent revolutionary activities, Aurobindo considered his cause to be not merely political but also profoundly religious. For him, nationalism was a divine a mission, and religion was the life-blood that flowed through the organic body of the Indian nation:

Nationalism is not a mere political program; Nationalism is a religion that has come from God. Nationalism is a creed which you shall have to live. . . . If you are to be Nationalist . . . you must do it in the religious spirit. . . . It is not by any mere political programme . . . that this country can be saved. . . . What is the one thing needful? . . . the idea that there is a Power at work to help India, that we are doing what God bids us.63

India in Aurobindo’s day had been offered up to “the secularity of autonomy and wealth, the pseudo-divinities upon whose altars Europe has sacrificed her soul.”64 Thus Indian youths must now be willing to sacrifice themselves—and to sacrifice their enemies—to divine cause of nationalism. Predictably, Aurobindo’s political activities soon attracted government attention. The police identified his publications as “the germ of the Hindu revolutionary movement,” condemning its “combination of religion and politics” as a “deliberate perversion of religious ideals to political purposes.”65 According to one official report, his project was “nothing but a gigantic scheme for establishing a central religious society, outwardly religious but in spirit, energy and work political. . . . [Aurobindo] has misinterpreted Vedantist ideas for his own purpose.”66 Finally, after the disastrous failure of the Muzaffarpur bombing, in May 1908, Aurobindo was arrested and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment in Alipur jail.

Offer sacrifice to me. Give for I am thirsty. Seeing me, know and adore the original Power, ranging here as Kālī, who . . . hungers to enjoy the heads of bodies of mighty rulers.

Sri Aurobindo, “Bhavani Bharati”

From the outset, the extremist leaders of the nationalist movement had made use of traditional religious and mythic themes to legitimate their revolutionary activity. The newspaper Jugantar, for example, employs the traditional model of the avatār or successive incarnations, of Viṣṇu sent to right the world and combat evil during each cosmic era: “the army of young men is the . . . Kalki incarnation of God, saving the good and destroying the wicked.”67 But surely the most powerful symbol employed by the revolutionaries was the Tantric goddess Śakti, particularly in her most frightening incarnation, Kālī.

Although Kālī has long appeared in Indian mythology as a goddess of military power and violence, her largely mythological figure was to assume a very concrete political role in the context of colonial Bengal. The most famous depiction of Kālī as the symbol of the motherland appears in Bankim Chandra’s fictional account of the Sannyāsī rebellion, Ānandamaṭh (The abbey of bliss). As we will see in more detail in chapter 3, it remains unclear whether Bankim’s original intention was to arouse anti-British revolutionary sentiments, or, on the contrary, to promote anti-Muslim but ultimately pro-British ideals. In any case, his novel later would be reinterpreted by the leaders of the nationalist movement as a weapon against the British and a model for revolution in the name of the Goddess.68

Perhaps most importantly, Bankim presented the image of the Goddess as the symbol of the Indian nation, the motherland, who is glorious in her original splendor and terrible in her present oppression: “Kālī was at once the symbol of the degradation of society under alien rule and a reservoir of unlimited power.”69 In one of the most remarkable passages in Bankim’s work, the Goddess appears as a fusion of past, present, and future. Inside the temple at the Abbey of Bliss, we are successively introduced to three goddesses, representing India in three historical periods. First we meet a beautiful image of Jagaddhatri as the “Mother, what once was,” as India’s golden past. Then we encounter the terrible Kālī, the bloodthirsty image of India in an age of foreign oppression: “Kali, covered with the blackest gloom, despoiled of all wealth. . . . The whole of the country is a land of death and so the Mother has no better ornament than a garland of skulls.” Last, we see a third image: a radiant, ten-armed goddess, who represents the future of India, the liberated nation in its original glory. “This is the Mother as she would be.”70

During the first years of the Swadeshi movement, Bankim’s novel and his image of the Goddess became favorite weapons of the revolutionaries. Newly appropriated by figures like Swami Vivekananda and Sister Nivedita (in her influential book Kālī the Mother [1907]), and seized upon by the extremist Bengali journals, the image of Kālī suddenly assumed a markedly political form. Aurobindo, in particular, was deeply inspired by Bankim’s work and his depiction of Mother India. Aurobindo’s translation of the famous song “Bande Mataram” (Hail to the Mother) became the battle cry of the nationalist movement: “It was the gospel of fearless strength and force which he preached under a veil and in images in Ananda Math.”71 However, Aurobindo also reinterpreted Bankim’s story, transforming it into a radically anticolonial call to revolution. In an even more explicit attempt to fuse the political and the religious domains, he drew on the traditional Tantric imagery of the Goddess as power on both the spiritual and revolutionary planes. As Kumari Jayawardena suggests, Aurobindo’s “emotional juxtaposing of Mother Goddess and Mother Country” was an effective image both psychologically and sociologically, which reflected at once the painful personal loss of his own mother and the traditional power of the Mother in the Indian mythic imagination: “Aurobindo’s uncompromising opposition to British rule was couched in the language of the cult of the Mother. Deprived of his own mother (who was insane) while in Britain for fourteen years, Aurobindo, in the political and spiritual phases of his life, constantly invoked the divine mother who would make India strong again.”72

The most influential work from Aurobindo’s early political period is a pamphlet entitled Bhawani Mandir, “The Temple of the Goddess,” published in 1905. Here, Aurobindo lays out his ideal of a secret religio-political organization, an order of young ascetics who would consecrate themselves to the liberation of the motherland. The ascetics would meet at a temple of the goddess Bhawani, a manifestation of Kālī, hidden in a secret place where her disciples would prepare for the armed struggle for independence. Very soon, Bhawani Mandir became among the most influential works in the national movement, a “handbook for revolutionary groups of Bengal.”73 As Gordon comments, “In Bhawani Mandir, as in the Tantras, the organ for emancipation and the urge for power go together. Aurobindo . . . syncretized religious elements and national messianism. Aurobindo gives fellow Indians a mission to ‘Aryanize’ the world.”74

The central figure of Bhawani Mandir is the goddess Śakti, who is nothing other than “pure power.” She is the world-creating divine energy, which has existed since the beginning of time, spinning creation into being; but now, in this most extreme age of crisis in the Kali yuga, she has become manifest even more openly, with the rise of new political forces and the spread of violent powers across the earth. Aurobindo even identifies Śakti as the underlying force beneath the power, wealth, expansion, and industrialization—including the growing military power of the West—that characterizes the modern world:

Wherever we turn our gaze, huge masses of strength rise before our vision, tremendous, swift and inexorable forces, gigantic figures of energy, terrible sweeping columns of force. All is growing large and strong. The Shakti of war, the Shakti of wealth, the Shakti of science are tenfold more mighty and colossal . . . a thousand-fold more prolific in resources weapons and instruments than ever before. . . . Everywhere the Mother is at work; from her mighty and shaping hands enormous forces of Rakshasas, Asuras, Devas are leaping forth. . . . We have seen the . . . rise of great empires in the West. . . . Some are Mleccha Shaktis . . . blood-crimson . . . others are Arya Shaktis bathed in . . . self-sacrifice; but all of them are the Mother in Her new phase. . . . She is whirling into life the new.75

But although she is at work everywhere in the modern world, Śakti is first and foremost the power of the Indian nation. While the forces of Westernization and industrialization manifest the demonic form of Śakti, harnessed to destructive ends, the Indian nation reveals the true, Aryan force of Śakti, turned toward spiritual ends. For Aurobindo, this divine Śakti is nothing other than the collective power of India, the combined energy of each individual Indian soul. “What is our mother-country? It is not a piece of earth, nor a figure of speech. . . . It is a mighty Shakti, composed of the Shaktis of all the millions of units that make up the nation.”76

But, Aurobindo continues, in these years of foreign rule the Indian had become weak and powerless, for he had become ignorant of his mother, Śakti. Like Vivekananda and other spiritual leaders of the early twentieth century, Aurobindo is painfully aware of the figure of the “effete babu” in the colonial imagination, the fawning, submissive, emasculated servant of British administration. Aurobindo, too, criticizes the passivity and weakness of Bengalis, calling them to a more virile, militant stance against their oppressors. He urges his countrymen to find a new inner strength and even “hypermasculinity”—the warrior ideal of the kṣatriya: “the one thing wanting . . . is strength—strength physical, strength moral, but above all strength spiritual.”77

As I would argue, the image of hypermasculine militant Bengali was the counterpart to the image of Kālī or Śakti as the powerful, destructive goddess. If the colonial imagination had juxtaposed the two images of the effete, emasculated babu and the lustful, violent Kālī, the revolutionary nationalists inverted and transformed these two images, juxtaposing the virile, strong Bengali warrior and the powerful goddess. As Nandy observes, the nationalists hoped to refashion and remake the self-image of the Bengali male himself. Whereas the British had continually ridiculed the Bengali babu as weak, effeminate, morally corrupt, and sexually perverse, the nationalists created an image of the Bengali male as powerful, militant, and hypermasculine.78 Hence the two images of the violent, militant goddess Kālī and the strong, hypermasculine Bengali revolutionary worked together as dialectical complements; and together, they represented the dialectical inversion of the imperial imagination, which had depicted the Bengali male as effeminate and sexually depraved and the Bengali female as excessively sexual and lustful. All of this could be schematically represented as in table 1.

TABLE 1

|

Male |

Female |

Imperial imagination |

Effeminate, weak, morally degenerate, licentious |

Overly sexual, violent, masculine |

Nationalist imagination |

Strong, virile, militant, morally pure, hypermasculine kṣatriya-hood |

Violent, strong, but not sexual |

At the same time, however, I would also suggest that the image of Śakti as Mother India played a more powerful role as a source of revolutionary inspiration, serving as a “dialectical image,” in Benjamin’s sense. For Aurobindo and the other leaders of the Jugantar group drew upon precisely those elements of the Goddess that the British most feared and despised—the violent and wrathful Mother-in-arms, who drinks human blood and wears garlands of severed heads. One of the most powerful images used by the national movement was taken explicitly from a traditional Tantric image of Kālī as Chinnamastā, who stands naked on the corpse of her husband, Śiva, holding her own severed head and drinking the blood that flows from it. Bipanchandra Pal, another leader in the revolutionary movement, offered a new interpretation of this traditional image: it is a representation of the motherland herself, which has been beheaded by the British and drinks her own blood in order to survive:

The Mother . . . became Kālī, the grim goddess, dark and naked wearing a garland of human heads—heads from which blood is dripping—and dancing on the prostrate form of Śiva. . . . This is the Mother as she is, dark because ignorant of herself, the heads with dripping blood are those of her own children destroyed by famine and pestilence; the jackals licking these drippings are . . . the decadence of social life and the prostrate form of Śiva means that she is trampling her own God under her feet.79

Now every Indian is called upon to serve as a “priest of Kālī” and to offer himself as a sacrificial victim to the Goddess, spilling his own blood in her defense: “The hero, the martyr . . . the grim fighter . . . the man who cannot sleep while his country is enslaved, the priest of Kali who can tear his heart out of his body and offer it as a bleeding sacrifice on the Mother’s altar.”80

However, the traditional Tantric image of Kālī was used not only to represent the humiliation of modern India, but also to arouse revolutionary fervor and violence. For since her earliest appearances in Hindu myth, Kālī has also been the symbol of destruction, bloodshed, and war, and hence an effective symbol for inciting political violence. As Aurobindo described the Dark Mother in his “Bhavani Bharati, Mother of India”:

Garlanded with the bones of men and girdled with human skulls, with belly and eye like a wolf’s hungry and poor, scarred on her back by the Titan’s lashes, roaring like a lioness who lusts for kill . . . filling the world with bestial sounds and licking her terrible jaws, fierce and naked, like eyes of a savage beast, thus did I see the Mother.

Thou naked art Kālī and utterly ruthless thou art. . . . I bow to Thee as the violent One, O Ender of worlds. . . . The mighty Mother of creatures has vanquished the age of Strife . . . in East and West, I hear the cry of the whole world hastening with the praise on its tongue to this country, the ancient Mother of the Vedas . . . firmly established in the Aryan country. Abide forever gracious in this land, O mighty One.81

Nothing now can satisfy this terrible Mother but the spilling of blood. The rage of Mother India in her violent form has been unleashed, and it cannot be pacified until it tastes the severed heads of her oppressors. As the radical newspaper Jugantar exhorts its readers,

The Mother is thirsty and is pointing out to her sons the only thing that can quench that thirst. Nothing less than human blood and decapitated heads will satisfy her. Let her sons worship her with these offerings and let them not shrink even from sacrificing their lives to procure them. On the day on which the Mother is worshipped in every village, on that day the people of India will be inspired with a divine spirit and the crown of independence will fall into their hands.82

Today, Aurobindo tells us, Bengalis are like Arjuna on the battlefield of Kuruksetra, on the verge of a holy struggle in which they “must not shrink from bloodshed” but be willing to give their own lives as sacrificial victims to the Goddess. Like Kuruksetra, the field of the great bloody “sacrifice of battle,” the soil of contemporary Bengal becomes the “cremation ground” upon which the violent Kālī unleashes her terrible power. But it is also the cremation ground of the great cosmic sacrifice at the end of time, the conflagration of worlds that signals the end of the old yuga and the violent dawn of the new.83

There is one force only, the Mother’s force—or, if you like to put it that way, the Mother is Sri Aurobindo’s Force.

Sri Aurobindo,

Sri Aurobindo on Himself and the Mother (1953)

Ironically, despite its powerful shock effect, the nationalists’ use of the image of Kālī does not appear to have been successful. For in many ways it could be said to have played back into the colonial view of India as morally depraved, a land of barbarous violence and perverse irrationality. As Nandy argues, the self-image created by the revolutionaries also backfired and worked against them: the “hypermasculine” ksatriya ideal of the revolutionaries still played by the rules of the colonial views of sexuality and manhood, replicating the European ideal of the virile, active male and the passive, submissive female. It could not succeed in overthrowing colonial ideology, but ultimately reinforced it.84 Likewise, the use of Kālī as a symbol of the nation in many ways only reaffirmed the Western view of Indians as morally degenerate, violent, and subversive. The solution that would win out, ultimately, was not the radical program of the extremists, but the ideal of passive resistance promoted by Mahatma Gandhi. By 1910, Aurobindo himself would abandon the revolutionary project and turn inward to the life of the spirit.

During his period of confinement in Alipur jail, Aurobindo claimed to have received an inner message from God, informing him that he had a worldwide purpose; he had been chosen “to uplift this nation” and “give the Indian people freedom for service of the world.”85 Upon his release from prison in 1910, Aurobindo left the active political realm and retired to Pondicherry, a small former French colonial town on the west coast. His own account of this change of heart was that he had received information that the government intended to search his office and arrest him; he then received a sudden command from above to go to Chandernagore in French India, where he lived in secrecy and solitary meditation. Immersed in the study of yoga and Indian philosophy, a small group of disciples eventually gathered around his ashram. Henceforth he began to write a vast body of works on various aspects of spirituality, along with poems, plays, and even epics. Despite urgings from many members of the nationalist movement, Aurobindo never reentered the political arena, claiming instead that he was having a greater impact on the course of world history through his spiritual teachings. When he was invited to preside over 1920 Indian Congress, he declined, saying, “I am no longer first and foremost a politician, but have commenced another kind of work with a spiritual basis.”86

After his withdrawal from the political life, Aurobindo began to envision a new ideal for the Indian nation and also to imagine a new role for the Divine Mother. Whereas, in his youth, Aurobindo had conceived of the Mother in Tantric terms, as Śakti, the terrible power of the nation in revolt, he now began to reimagine the Goddess in a far more benevolent and seemingly “un-Tantric” form. She was now the ideal of pure Spirit, the embodiment of India as the land of literature, culture, art, and above all religion. Here I would like to borrow some insights from Partha Chatterjee and his analysis of the changing construction of the Bengali bhadralok (“respectable classes”) identity in nineteenth-century Bengal. Many middle-class Bengalis, Chatterjee argues, withdrew from the outward political sphere, dominated as it was by foreign colonial power. Instead, they turned inward to the private sphere of religion and domesticity—“an inner domain of sovereignty far removed from the area of political context with the colonial state”—as the stronghold of traditional Indian values. For “the strategy of survival in a world that is dominated by the rich and powerful is withdrawal. Do not attempt to intervene in the world, do not engage in futile conflict.”87

A critical part of the construction of Indian national identity, as an inner private sphere in opposition to the colonially dominated public sphere, was the dichotomy of the “material West and the spiritual East.” Even as early as 1902, Aurobindo had drawn a sharp distinction between the materialism or “morbid animalism” of the West and the eternal religion of India.

Science had freed Europe from the shackles of Christianity but it had not provided a new system of values to replace the one it had rendered obsolete. The result . . . was an upsurge of “morbid animalism” demonstrating Europe’s “neurotic tendency to abandon itself to its own desires.” . . . Hinduism alone among the great embodiments of the old religious and moral spirit did not . . . stand naked to the assaults of Science. Hinduism therefore could serve as the framework for a new world outlook.88

Later in life, Aurobindo would make this dichotomy even more explicit, identifying “the two principal ways of regarding existence—the spirituality preserved in the religious traditions of the East and the practicality represented by the political and economic systems of the West.”89 As Halbfass points out, Aurobindo may have withdrawn from the political arena into the spiritual realm in the second half of his life, yet there is a deep continuity between the two phases. Both are attempts at Indian self-assertion, attempts to identify a domain of national and religion identity, a uniquely Eastern cultural sphere, set apart from that of the West: “Hindu nationalism and spiritualistic universalism dominate the two major phases in Aurobindo’s Neo-Hindu life. They are . . . complementary means of self-assertion.”90

Yet Aurobindo’s new nonpolitical, spiritual ideals would continue to center on the overarching figure of the Great Goddess, the Mother. The striking irony, however, is that Aurobindo would later come to identify the Mother, not with the violent, bloodthirsty, and militant Tantric goddesses Kālī, Durgā, or Chinnamastā, but instead with one particular woman, and most remarkably, a Western woman—Mira Alfassa (later Mira Richards, 1878–1973). Born in Paris of a Sephardic Jewish family, Richards had been a student at the École des Beaux Arts and part of the artistic avant-garde scene in Paris. She had also begun from an early age to dabble in occultism and Eastern religions, and was soon attracted by Aurobindo’s unique blend of Western philosophy and Indian mysticism. Leaving behind home and children, she joined Aurobindo and became his disciple in 1914. As his new religious community began to gather around him, Aurobindo eventually elevated Mira to a divine status nearly equal to his own. After his own wife’s death in 1918, Aurobindo would grow increasingly closer to Mira. When her husband left her in 1920, Mira was moved into the master’s house, occupying the quarters adjacent to his apartment, where she would remain until his death. Not only did Mira progressively take over all the details of running the growing ashram, but, by 1926, she came to be revered as none other than the Mother herself, the manifestation of the supreme Śakti in human form.91 As Aurobindo described her,

There is one divine Force which acts in the universe and in the individual. . . . The Mother stands for all these but she is working here in the body to bring down something not yet expressed in this material world so as to transform life here. . . . [Y]ou should regard her as the Divine Shakti. . . . She is that in the body, but in her whole consciousness she is also identified with all other aspects of the Divine.92

As Aurobindo explained in a letter of 1926, Mira was none other than his own counterpart and complement in the spiritual realm: “Mother and I are one but in two bodies.”93 While he himself was the embodiment of the masculine, spiritual Puruṣa—which, rather strikingly, he now interprets as passive and unacting—the Mother represents the feminine, practical element of Prakṛti or Śakti—which is inherently active and dynamic. As Heehs comments, “His personal force, representing the Purusha element, acted in the realm of spiritual knowledge, while Mira’s representing the Shakti element, was practical. . . . Without the Mother . . . his conception of a divine life on earth could never have been embodied.”94 Together, he and the Mother had been working as the primordial male and female principles moving through all history, guiding the evolution of humankind. Not only did their divine interaction lie at the font of creation and within all the world’s great events, but it even determined the course of contemporary history, including the onset and final end of World War II. “The War ended in 1945, with the victory of the Allies, as Sri Aurobindo had willed.”95

This mother is no longer the violent Kālī of the tantras or the bloodthirsty Śakti of the nationalist movement, to be worshiped by strong kṣatriya warriors with offerings of severed heads; rather, it is a loving mother to whom the soul must surrender itself like a child at her breast: “when you are completely identified with the Divine Mother and feel yourself to be no longer another separate being . . . but truly a child and eternal portion of her force.”96 As Nandy comments on this striking paradox, Aurobindo’s choice of a Western woman as his Śakti was his final attempt to resolve the profound oppositions in his life, his long struggle between East and West, between his English education and his search for an Indian identity: “For him the freed East had at last met the non-oppressive West symbolized by the Mother.”97 Hence, we might add to our schema of contrasting sexual-symbolic images a third pair, the new Male and Female archetypes of Aurobindo’s postpolitical, spiritual phase (see table 2).

Following the lead of Partha Chatterjee, I would suggest that the rather curious union of Aurobindo and Mira Richards is a profound symbol of the deeper ambivalence underlying Indian nationalism as a whole. Aurobindo, like many members of the nationalist movement, struggled to create a uniquely Indian, Hindu identity—an inner, spiritual, and cultural private sphere—set in opposition to the political and material public sphere of the West.98 Yet at the same time, he clearly absorbed many of the basic structures and oppositions of the West, including the opposition between the inner, private sphere and the outer, politically active, public sphere. The choice of a Western woman as Śakti—a spiritual mother who replaces the violent, destructive Śakti of his revolutionary nationalist period—is a profound symbol of the deeper conflicts at work the hearts of Aurobindo and other intellectuals of the early twentieth century. It is a clear embodiment of his own attempt to identify a uniquely Indian or Eastern identity, in opposition to the material West. And yet this identity is itself constructed with Western categories and terms. As Halbfass comments, “Even in their rejection of . . . European ideas and orientations, modern Indian thinkers are not free from such ideas. Explicit or implicit reference to the West, and membership in a Westernized world, is an irreversible premise of modern Indian thought.”99

TABLE 2

|

Male |

Female |

Colonial imagination |

Effeminate, weak, morally degenerate, licentious |

Overly sexual, violent, masculine |

Nationalist imagination |

Strong, virile, militant, morally pure, hypermasculine kṣatriya-hood |

Violent, strong, but not sexual |

Aurobindo’s postrevolutionary imagination |

Spirit (Purusa), passive, inward, inactive, the Spiritual East |

Power, Nature (Prakṛti), outward, active, the material West |

In the face of his failure as a revolutionary opponent of Western domination in the name of the Tantric mother Kālī, Aurobindo seems to have turned instead to a more complex, ambivalent, though perhaps more tolerable solution. He has now tried to accommodate the power of the West—the power of European technology, science, and material advancement—while at the same time asserting the ultimate spiritual superiority, and seeming political impotence, of the East. While the dangerous, violent Śakti of the Tantras has failed, a new hope lies in the attempt to incorporate the Śakti of the West.

The pride of prosperity throws man’s mind outwards and the misery . . . of destitution draws men’s hungering desires likewise outwards. These two conditions alike leave man unashamed to place above all other gods, Shakti the Deity of Power—the Cruel One, whose right hand wields the weapon of guile. In the politics of Europe drunk with Power we see the worship of Shakti.

Rabindranath Tagore, “Letters from an On-Looker” (1919)

In sum, the shifting representations of Tantra and the Tantric goddess might be seen as a metaphor for the changing image of the Indian nation itself in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A powerful dialectical category, Tantra passed back and forth between colonial and anticolonial imaginations, used by some to attack the criminality of the Indian subject and by others to instigate revolution against the imperial master. If the colonizers projected onto Tantra the “savagery they yearned to colonize,” in the form of criminal Thuggee and subversive agitators, the leaders of the radical nationalist movement appropriated Tantra as the awesome power of the Indian people that could not be controlled. The heart of this play of representations was the Tantric goddess of power—a goddess who embodied all the darkest fears of subversion within the colonial imagination and all the hopes for violent revolt among the extremists. She is thus a fitting symbol for the birth, hope, and failure of the revolutionary nationalist movement.

Ironically, the use of violence and power did not prove to be a viable solution for either colonizer or colonized. The radical ideal of the Tantric Śakti gave way to passive resistance of Gandhian nationalism and the relatively peaceful withdrawal of the British from India in 1947. Thus, like many Western-educated Indians of his day, Aurobindo ultimately seems to have sought a kind of compromise, a reconciliation between the passive spirituality of the East and the active power of the West, now embodied in his seemingly “un-Tantric” consort, Mira Richards. Hence, we might be tempted to follow the lead of the members of the Subaltern Studies collective, such as Ranajit Guha, by regarding Aurobindo’s retreat from active politics as yet another example of “the historic failure of the nation to come to its own.”100 That is, it could be seen as the failure of genuine resistance, a disappointing compromise with the West. I would argue, however, that Aurobindo’s solution is better understood as another example of a strategy for dealing with a situation. Like Rāmmohun Roy’s paradoxical use of the Mahānirvāṇa Tantra in the service of his own cultural reforms, Aurobindo’s turn from the dark Tantric Śakti to the more benign Western Śakti was an ingenious, through perhaps not entirely successful, attempt to resolve the “situational incongruities” of India under late colonial rule.

I would like also to point out some larger comparative implications of this discussion of Tantra and colonial politics. The shifting role of Tantra in the British and Indian imaginations sheds some important light on the role of religious symbolism in the formation of political identities, particularly during periods of colonial rule. As Ranajit Guha, Partha Chatterjee, and others have acknowledged, the power of religious symbolism has long been one of the least understood and most neglected problems in the literature on subaltern studies.101 Commonly reduced to a mask of political ideology or an instrument of domination, religious symbols have seldom been discussed as weapons of insurgency or tools for revolutionary struggle. As I hope to have shown in the case of Tantra and the goddess Śakti, religious symbols can indeed be used as masks of ideology, to reinforce a given political arrangement; but they can also be manipulated as profound dialectical images, appropriated by dissident factions to subvert the status quo and even instigate revolutionary struggle. Like all symbols, however, the image of the Goddess is an ambivalent, even contradictory one, which leads her devotees to both heroic victories and tragic failures in their fight for independence.