What I tell you must be kept with great secrecy. This must not be given to just anyone. It must only be given to a devoted disciple. It will be death to any others.

If liberation could be attained simply by having intercourse with a Śakti [female partner], then all living beings in the world would be liberated just by having intercourse with women.

Kulārṇava Tantra (KT 2.4, 2.117)

Because the science of Tantra was developed thousands of years ago . . . many of the techniques are not relevant to the needs of the contemporary Western lover. . . . I see no need for repetition of long Sanskrit mantras . . . or the strict ritualization of lovemaking. . . . So while I have retained the Tantric goal of sexual ecstasy, I’ve developed new approaches to make this experience accessible to people today. High Sex weaves together the disciplines of sexology and humanistic psychology to give the Western lover the experience of sexual ecstasy taught by Tantra but using contemporary tools.

Margo Anand, The Art of Sexual Ecstasy (1989)

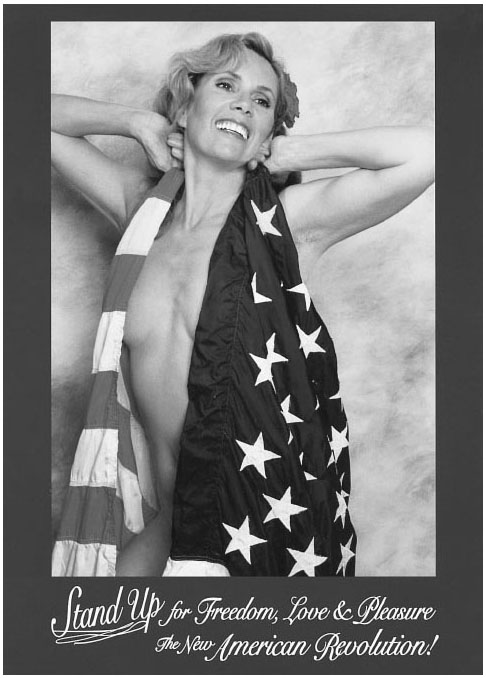

Inspired by the new valorizations of Tantra by Eliade, Zimmer, and more popular authors like Joseph Campbell, Tantra began to enter in full force into the Western popular imagination of the twentieth century. Already in the early 1900s we find the foundation of the first “Tantrik Order in America”—an extremely scandalous, controversial affair, much sensationalized by the American media—and by the 1960s and 1970s, Tantra had become a chic fashion for Western pop stars, as Jimi Hendrix began displaying yantras on his guitar and Mick Jagger produced a psychedelic film, Tantra, depicting the five M’s. Taking Eliade’s positive reinterpretation a step further, Tantra is now celebrated as a “cult of ecstasy”: an ideal wedding of sexuality and spirituality that provides a much needed corrective to the prudish, repressive, modern West. In the process, it has also spawned a variety of new spiritual forms, such as American Tantra, neo-Tantra, and even the Church of Tantra (figure 10). At the same time, these transformed versions of Tantra have been reappropriated by Indian authors. In a complex cross-cultural exchange or “curry effect” between India and the West, we not only find neo-Tantric gurus like Osho-Rajneesh, but even a heavy-metal band in Calcutta called “Tantra.” Amid the ever increasing circulation of material and spiritual capital throughout the global marketplace, it seems that Tantra has been exported to the West, where it has been processed, commodified, and reimported by the East in a new form.

Figure 10. American Tantra, “New Millennium Flag Bearer,” from the Third Millennium Magic web site (http://www.3mmagic.com/at_main.html). Courtesy of Third Millennium Magic, Inc. © www.3mmagic.com 1999.

An examination of the history of Tantra and its contemporary manifestations shows that it has undergone profound transformations in the course of its long, convoluted “journey to the West” and back. For most contemporary American readers, Tantra is basically “spiritual sex,” the “exotic art of prolonging your passion play” to achieve “nooky nirvana.”1 This would seem to be an image of Tantra that is very different from that in most Indian traditions, where sex often plays a fairly minor, “unsexy” role and there is typically far more emphasis on guarded initiation, esoteric knowledge, and elaborate ritual detail. At present there is a profound shift in the imagining of Tantra—a shift from Tantra conceived as dangerous power and secrecy to Tantra conceived as healthy pleasure and liberated openness. This shift is exemplified by the two epigraphs for this chapter. The first, the quote from the Kulārṇava Tantra, warns of the perils of revealing secrets to the uninitiated masses. Kula practice, it is true, involves rites of sexual intercourse and consumption of wine, but these must occur only in strictly guarded esoteric contexts; in the hands of the uninitiated masses, they would lead to moral ruin and depravity. The contemporary neo-tāntrika, however, takes the opposite position. Jettisoning the old ritual trappings as outdated and irrelevant, the neo-tāntrika takes only the most expedient elements of these age-old techniques, mixes them with contemporary self-help advice, and adapts them to a uniquely late-capitalist consumer audience.

Since at least the time of Agehananda Bharati, most Western scholars have been severely critical of these new forms of pop Tantra or neo-Tantra. This “California Tantra,” as Georg Feuerstein calls it, is “based on a profound misunderstanding of the Tantric path. Their main error is to confuse Tantric bliss . . . with ordinary orgasmic pleasure.”2 My own view, however, is that “neo” or “California” Tantra is not “wrong” or “false,” any more than the Tantra of the Mahānirvāṇa or other traditions; it is simply a different interpretation for a specific historical situation. As such, the historian of religions must take it very seriously as an example of a new adaptation of a religious form to a new social and political context.

Above all, the popular fascination with Tantra as “spiritual sex” is closely related to the larger preoccupation with sexuality in contemporary culture as a whole, which is now filled with sexual discourse, imagery, and advertising. As Angus McLaren comments, “Today’s media, while claiming to be shocked by the subversiveness of carnal desires, deluge the public with explicit sexual imagery to sell everything from Calvin Klein jeans to Black and Decker power drills. Sexuality. . . has invaded every aspect of public life. Sexual identity has become a key defining category in the twentieth century.”3 Yet, as Foucault argues, it is a common misconception to suppose that the history of sex in the West is a progressive narrative of liberation from Victorian prudery. Just as the Victorian age was not simply an era of repression and silence, our own age is perhaps not the age of sexual revolution that we commonly imagine it to be. Our sexual liberation has been accompanied by new forms of regulation, backlash, and conservatism. What has happened, however, is that we have produced an incredible body of discourse on the subject, a kind of “over-knowledge” or “hyper-development of discourse about sexuality.”4 Thus it is more useful to think of sexuality as a constructed and contested category, whose boundaries have been renegotiated in each generation. The category of “sexuality” is itself a recent invention, a product of the late nineteenth century, by no means static—ever imagined anew in the changing political contexts of the past one hundred years.5

As I will argue in this chapter, the contemporary preoccupation with Tantra has been part and parcel of our larger preoccupation with and anxieties about sexuality, a source of both titillating fascination and moralizing censorship. I will examine three transformations in the transmission of Tantra to the United States: the founding of the scandalous Tantrik Order in America by Pierre Bernard; the “sex magick” of Aleister Crowley and his followers; and the equation of Tantra with sexual liberation during the countercultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. But this preoccupation with Tantric sex has also been reimported by India via a complex feedback loop, through such figures as Osho-Rajneesh, Chogyam Trungpa, and Swami Muktananda. Finally, as we can see in the rapidly proliferating web sites, Tantra appears to have shattered the boundaries between the “spiritual East and the material West.” Today, anyone with a fast modem and Internet access may attend the Church of Tantra, sample the Sensual Spiritual Software System, and discover Ecstasy Online.

These new forms of Tantra are in many ways well suited to our unique socioeconomic context. With its apparent union of spirituality and sexuality, sacred transcendence and material enjoyment, Tantra might well be said to be the ideal religion for contemporary consumer culture—what I would call, adapting Fredric Jameson’s phrase, “the spiritual logic of late capitalism.” Using some insights of Jameson and others, I will argue that there is an intimate relationship between the recent fascination with Tantra and the current socioeconomic situation, which has been variously described as late capitalism, postindustrial capitalism, or disorganized capitalism. It is precisely this kind of “fit” with late-capitalist society—a fit not unlike that of Weber’s Protestant ethic and early capitalism—that characterizes many new appropriations of Tantra. Indeed, Tantra might be said to represent the quintessential religion for consumer capitalist society at the turn of the millennium.

Where can tantra happen? It can only happen in American and Western Europe. . . . Tantrism may happen here and maybe it has started right here in Boulder, Colorado, 80302.

Agehananda Bharati,

“The Future (if Any) of Tantrism” (1975)

In 1975, at the peak of the New Age movement and when the Naropa Institute was a burgeoning Mecca for Tantric spirituality, Agehananda Bharati made the qualified prediction that the United States might become the new center for the revival of Tantra. India, he believed, had become so morally repressive that it could no longer provide any space for Tantra; the affluent West alone had the openness and freedom to accommodate Tantra in the modern world. Yet he also warned of the real dangers of this transmission of Tantra to the United States, where it could be (and in his day already was being) all too easily misinterpreted as a simple excuse for self-gratification and hedonism:

It is conceivable that the more affluent . . . of the West, particularly Western Europe and north America, might espouse some form of tantrism. . . . Some steps have been made, but probably in the wrong directions: the frustrated middle aged North American lusting for the mysterious has opened a door for tantrism to enter. However, I feel that this entry is dangerous and . . . that it would have havoc out of tantrism.6

It would seem that both Bharati’s prediction and his warning have been realized. The West, particularly America, has indeed become a fertile new land for the spread of Tantra, yet it has also offered new opportunities for its gross misinterpretation and reckless abuse.

The Western appropriation of Tantra had already begun in the late nineteenth century, with the Theosophical Society and Madame Blavatsky’s descriptions of the mysterious “masters” who dwell in forbidden Tibet, the heartland of Vajrayāna Buddhism. The massive text of her Secret Doctrine is alleged to be based on a mysterious Tibetan text discovered by Blavatsky. What is most striking, however, is that Blavatsky did not identify Tibetan Buddhism as “Tantra”; on the contrary, influenced by Orientalist attitudes, she went to some pains to distinguish it from the disreputable tradition of black magic and hedonism known as Tantra. While Tantra could be understood in a spiritual sense as a form of “white magic,” most of its modern forms are degenerate “necromancy” and “invocations to the demon,” comparable to Western black magic: “The Tantras . . . are the embodiment of ceremonial black magic of the darkest dye. A Tantrika . . . is synonymous with ‘Sorcerer.’ . . . [T]hose Kabalists who dabble in the ceremonial magic described . . . by Eliphas Levi are as full blown Tantrikas as those of Bengal.”7

It was not until the beginning of this century, and particularly in the United States, that Tantra was newly appropriated in a positive form in the Western popular imagination. No longer conceived as a religion of black magic and occult power, Tantra began to be identified more and more with the pursuit of sensual pleasure and erotic bliss. This was above all the case following Richard Burton’s scandalous translation of the classic Indian erotic manual, the Kāma Sūtra, a text that was originally published in 1883 only for private circulation but that was soon pirated and sold widely throughout Europe. The Kāma Sūtra itself, of course, really has nothing to do with “Tantra.” In the Victorian imagination, however, the dark secrets of the Tantras and the tantalizing secrets of the Kāma Sūtra would soon blend together and take on a variety of new forms.8 And three of the most interesting of these new forms were perhaps the founding of the first Tantrik Order in America, the spread of Crowleyian “sex magick,” and the “yoga of sex” that emerged with the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s.

Wily con man, yogi, athlete, bank president, founder of the Tantrik Order in America . . . the remarkable “Doctor” Bernard was all of these. He was also the Omnipotent Oom, whose devoted followers included some of the most famous names in America.

Charles Boswell,

“The Great Fuss and Fume over the Omnipotent Oom”I’m a curious combination of the businessman and the religious scholar.

Pierre Arnold Bernard

Not only was he the first man to bring Tantra to America, but Pierre Bernard was also surely one of the most colorful and controversial figures in early-twentieth-century American history. Described as “both a prophet and showman,” Bernard was a man “who could lecture on religion with singular penetration and with equal facility stage a big circus, manage a winning ball team or put on an exhibition of magic which rivaled Houdini.”9 Infamous in the press as “the Omnipotent Oom,” Bernard claimed to have traveled to the mystic Orient in order to bring the secret teachings of Tantra to this country and to found the first “Tantrik Order in America,” in 1906. Surrounded by controversy and slander regarding the sexual freedom he and his largely female followers were said to enjoy, Bernard is in many ways an epitome of Tantra in its uniquely American incarnations.

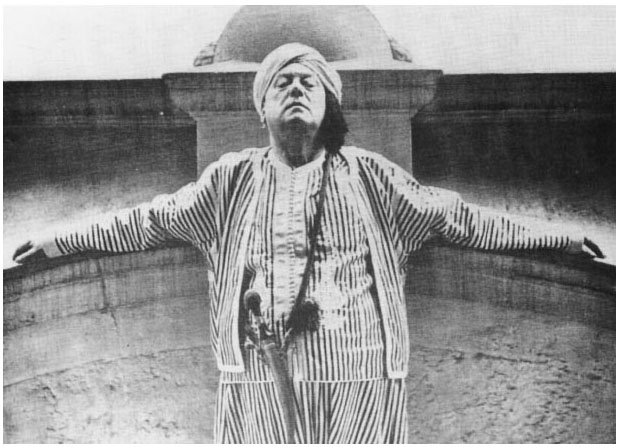

Virtually nothing is known about Bernard’s early life; in fact, he seems to have gone to some lengths to conceal his real background behind a veil of fictitious identities and false biography, often using the persona of “Peter Coons” from Iowa.10 Probably born in 1875 to a middle-class family from California, Bernard left home in his teens to work his way to India in order to study the “ancient Sanskrit writings and age old methods of curing diseases of mind and body.” After studying in Kashmir and Bengal, he won the title “Shastri” and was supposedly initiated into the mysteries of Tantric practice. Returning to America, and now introducing himself with the title of “Doctor,” he worked at various odd jobs in California and began to study hypnotism. By 1900, he had become moderately famous as a master of self-hypnosis who could use yogic techniques to place himself in a state simulating death (figure 11). It is also likely that Bernard received instruction in Tantric practice from one Swami Ram Tirath, an Indian yogi who had come to California in the early 1900s, who praised Bernard as a man of “profound learning,” comparable to “the Tantrik High Priests of India.”11

Figure 11. Pierre Bernard, demonstrating the Kālī mudrā, or simulation of death. From International Journal of the Tantrik Order 5, no. 1 (1906).

In 1904, Bernard established a clinic in San Francisco where he taught his own versions of self-hypnosis and yoga; the clinic eventually became known as the Bacchante Academy. Even by then, Bernard had become something of a scandal in the California press, who charged that the academy “catered to young women interested in learning hypnotism and soul charming—by which they meant the mysteries of the relations between the sexes.”12 Sometime in the years 1906–7, Bernard founded the first Tantrik Order in America, with an accompanying journal—the International Journal of the Tantrik Order—whose charter document for initiation reads as follows:

As a tear from heaven he has been dropped into the Ocean of the tantrik brotherhood upon earth and is moored forevermore in the harbor of contentment, at the door to the temple of wisdom wherein are experienced all things; and to him will be unveiled the knowledge of the Most High. . . .

Armed with the key to the sanctuary of divine symbolism wherein are stored the secrets of wisdom and power, he . . . has proven himself worthy to be entrusted with the knowledge . . . to soar above the world and look down upon it; to exalt the passions and quicken the imagination . . . to treat all things with indifference; to know that religion is the worship of man’s invisible power . . . to enjoy well-being, generosity, and popularity. . . . He has learned to love life and know death.13

After the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, Bernard left California and relocated in New York City, where he opened his “Oriental Sanctum” in 1910. Teaching haṭha yoga downstairs and offering secret Tantric initiation upstairs, the Oriental Sanctum quickly became an object of scandal in the New York press: the notorious “Omnipotent Oom” was charged with kidnapping and was briefly imprisoned, though the charges were later dropped. “I cannot tell you how Bernard got control over me,” said one of the alleged kidnappees, Zella Hopp. “He is the most wonderful man in the world. No women seem able to resist him.”14 Similar controversy surrounded the “New York Sanskrit College,” which Bernard founded a few years later. The press reported “wild Oriental music and women’s cries, but not those of distress.”15

By 1918 Bernard and his followers had moved out to a seventy-two-acre estate in Upper Nyack, New York—a former girls’ academy that he renamed the Clarkstown Country Club, making it the site of his own “utopian Tantric community.” A sumptuous property with a thirty-room Georgian mansion, the club was designed to be “a place where the philosopher may dance, and the fool be provided with a thinking cap!”16 Eventually, he would also purchase a huge property known as the Mooring and then later open a chain of Tantric clinics, including centers in Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York City, as well as a Tantric summer camp for men in Long Island. His clinics were well known for attracting the most affluent clients—“mostly professional and business men and women from New York,” including Ann Vanderbilt, Sir Paul Dukes, composer Cyril Scott, and conductor Leopold Stokowski, among others.17 According to Town and Country magazine of 1941, “Every hour of the day limousines and taxies drove up to the entrance of the Doctor’s New York clinic. In the marble foyer behind the wrought-iron portal of 16 East 53rd Street, a pretty secretary handled appointments.”18 Hence, it is not surprising that Bernard quickly achieved a remarkable degree of wealth, fame, and status: “Almost overnight, Oom found himself showered with more money than he had ever dreamed of and chieftain of a tribe of both male and female followers. . . . This tribe . . . would number well over 200, and would carry on its roster some of the best-known names in America.”19 And much of the appeal of Bernard’s teachings, as well as the scandal they generated, centered around his views of sexuality.

Love, a manifestation of sexual instinct, is the animating spirit of the world.

Pierre Bernard,

“Tantrik Worship: The Basis of Religion” (1906)

Many of Bernard’s Tantric teachings appear to have been surrounded with an aura of secrecy, considered so profound and potentially dangerous that they had to be reserved for the initiated few. Thus the International Journal of the Tantrik Order warns that “whoever has been initiated, no matter what may be the degree to which he may belong, and shall reveal the sacred formulae, shall be put to death.”20 According to the police reports from a raid on Bernard’s clinic, entry involved a secret signal and complex series of taps on the bell. There also seems to have been a certain hierarchy of disciples, with the lower-level initiates performing physical exercises downstairs, while the “inner circle”—the “Secret Order of Tantriks”—engaged in the more esoteric rituals upstairs:

Downstairs, they found a bare room where Oom’s physical culture clients, paying $100 bite, toiled through exercises designed to produce the body beautiful. Upstairs . . . on canvas-covered mattresses, Oom’s inner-circle clients participated in secret rites. . . . [T]he upstairs customers, following physical examinations, had to pay large sums and then sign their names in blood before they could be initiated into the cult.21

The popular press offered some vivid and probably somewhat fictional accounts of Bernard’s secret Tantric rituals, occult initiations, and arcane esoteric techniques.

During Tantrik ceremonies, Oom sat on his throne wearing a turban, a silken robe and baggy Turkish pants, and flourished a scepter. While so engaged, he invariably smoked one of the long black cigars to which he was addicted. . . .

A frequent Tantrik ceremony involved the initiation of new members. “To join the order,” an Oomite later disclosed, “the novitiate must first have confessed all sins, all secret desires, all inner thoughts; must then promise to abide by Doctor Bernard’s orders and . . . take the Tantrik vow.”

The novitiate looks upon Doctor Bernard as a high priest—indeed, as a sort of man-god. He kneels before Doctor Bernard and recites: “Be to me a living guru; be a loving Tantrik guru.” Then all present bow their heads as though in church and repeat in unison: “Oom man na padma Oom.” It is sung over and over in a chanting monotone, like the beating of drums in a forest, and is supposed . . . to induce a state of ecstasy.22

There does appear to have been some real need for the secrecy in Bernard’s Tantric practice—particularly in the moral environs of early-twentieth-century America. According to the accounts that came out of Bernard’s Nyack Country Club, much of the spiritual practice there centered around full enjoyment of the physical body and complete liberation of sexual pleasure. As we read in the International Journal of the Tantrik Order, the human body is the supreme creation in this universe and the most perfect place of worship—a truly embodied, sensual worship that requires no priesthood or churches of stone: “The trained imagination no longer worships before the shrines of churches, pagodas and mosques or there would be blaspheming of the greatest, grandest and most sublime temple in the universe, the miracle of miracles, the human body.”23

Like dance and yoga, sex is thus a spiritual discipline, a means of experiencing the divine within the physical body. “The secret of Bernard’s powers,” one observer comments, was “to give his followers a new conception of love. . . . Bernard’s aims are . . . to teach men and women to love, and make women feel like queens.”24 (Thus, in his Tantrik journal, Bernard even spells the word tantra in devanāgarī characters comprised of tiny hearts.) As we read in his article “Tantrik Worship,” the sex drive is in fact “the animating spirit of the world.”

The animating impulse of all organic life is the sexual instinct. It is that which underlies the struggle for existence in the animal world and is the source of all human endeavor. . . . That affinity which draws the two sexes together for the . . . production of a new being, that overmastering universal impulse, is the most powerful factor in the human race and has ever been the cause of man’s most exalted thought.25

Yet in modern Western culture, the mysteries of sexual love have been stupidly repressed, relegated by self-righteous prudes to the realm of depravity. Today, “matters pertaining to the sexes are generally avoided, and we are taught that the sexual appetite is an animal craving that should be concealed,” such that most Americans now “are blind to the vast importance of the sexual nature” and fail to realize that it is in fact the “wellspring of human life and happiness.”26 According to one disciple’s account, Bernard was one of the only teachers of that time who recognized the natural beauty and power of sex, which is nothing other than an expression of our union with the divine: “He teaches the Oriental view of love as opposed to the restrained Western idea. Love . . . is akin to music and poetry. It unites men and women with the infinite.”27

Bernard’s wife, Blanche de Vries, also became a teacher of Oriental dance and haṭha yoga. She would eventually develop her own sort of “Tantric health system,” which she marketed very profitably to the wealthy New York upper-class society, who were increasingly obsessed by matters of physical health and beauty. Among her more affluent patrons, for example, was Mrs. Ogden L. Mills, a stepdaughter of the Vanderbilt family. As Mrs. Bernard commented, the Tantric teaching of love is the most-needed remedy to modern America’s social ills, most of which derive from repression, prudery, and self-denial: “Half the domestic tragedies . . . and not a few suicides and murders in America are due to the inherent stupidity of the average Anglo-Saxon man or woman on the subject of love. We will teach them, and make our adventure a great success.”28 Apparently, Bernard also believed that for certain individuals (particularly overly repressed women of the Victorian era) more drastic, surgical measures might be needed to liberate their sexual potential. Sexually unresponsive or “desensitized women” could be helped by a form of partial circumcision, in which the clitoral hood was surgically removed—an operation believed to improve female receptivity by exposing the clitoral gland to direct stimulation.29

Not surprisingly, the popular press of the day took no end of delight in sensationalizing Bernard’s scandalous Tantric practices and soon dubbed him the “Loving Guru.” Bernard’s clinics represented something terribly shocking yet also tantalizing in the American imagination—something deliciously transgressive, in a world where sex for the sake of procreation within heterosexual marriage was the unassailable pillar of decent society: “The rites are grossly licentious and . . . a couple skilled in the rites . . . are supposedly able to make love hour after hour without diminution of male potency and female desire.”30

It seems inevitable that Bernard’s Tantric clinics would have elicited some complaints from his neighbors and attracted the attention of the authorities. One F. H. Gans, who occupied an apartment across the way, summed up the neighborhood grievance: “What my wife and I have seen through the windows of that place is scandalous. We saw men and women in various stages of dishabille. Women’s screams mingled with wild Oriental music.”31 In Nyack, where Bernard was a respected citizen, the authorities received a host of complaints about this scandalous Tantric clinic; reluctantly, the state police investigated, and riding into the estate on horseback:

Nyack concluded Oom was running a love cult. The local prudes clucked and gasped their alarm. Oom, obviously, was a danger to the young of the community and would have to be run out of town.

But the Nyack police refused to act. Oom was a big taxpayer. So the prudes complained to the New York State Police, then a recently formed, eager-beaver organization. . . . The night they received the complaint, a squad of troopers galloped to Oom’s estate and swung down from their saddles near the main building.32

After his rise to celebrity, soon followed by his rapid descent into scandal, Bernard seems to have retired into a relatively quiet later life. Enjoying an affluent lifestyle, Bernard was known for his lavish wedding celebrations, his generous patronage of professional baseball and boxing, and his investment in sporting venues like baseball stadiums and dog tracks. Eventually he assumed a more respectable position in Nyack society, becoming president of the State Bank of Pearl River in 1931. With a fondness for collecting fine automobiles, such as Rolls-Royces, Stutzes, and Lincolns, Bernard is said to have been worth over twelve million dollars at his peak. Remembered as a “curious combination of the businessman and the religious scholar,” he died in New York City in 1955, at the age of 80.

In sum, we might say that the enigmatic and colorful character of Pierre Bernard is important to the history of Tantra for three reasons. First, he was a bold pioneer in the transmission of Tantra to America, where it quickly took root and flourished; second, he was one of the first figures in the larger reinterpretation of Tantra as something primarily concerned with sex and physical pleasure; and finally, like so many later American Tantric gurus, he generated intense scandal and slander from the surrounding society, foreshadowing Tantra’s role in the American imagination as something wonderfully tantalizing and transgressive. As such, Oom’s popular brand of Tantra would help lay the foundation for the new synthesis of Tantra and Western sex magic that later emerged.

True Sex-power is God-power.

Paschal Beverly Randolph,

The Ansairetic Mystery (ca. 1873)Mankind must learn that the sexual instinct is . . . ennobling. The shocking evils which we all deplore are due to perversions produced by suppressions. The feeling that it is shameful and the sense of sin cause concealment . . . creates neurosis and ends in explosion. We produce an abscess and wonder . . . why it bursts in stench and corruption. . . . The Book of the Law solves the sexual problem completely. Each individual has an absolute right to satisfy his sexual instinct.

Aleister Crowley, The Confessions of Aleister Crowley (1968)

Once the seeds of Tantra had been sown in this country, they soon began to proliferate wildly in the fertile soil of the American imagination, mingling with a number of existing Western esoteric traditions. Most modern forms of sexual magic, I would argue, are largely the fusion of Indian Tantric techniques, as reinterpreted by figures like Bernard and by Western occult movements emerging from the Masonic, Rosicrucian, and Kabbalistic traditions.

Sex, magic, and secrecy had long been associated in the Western imagination. From the early Gnostics to the Knights Templar and the Cathars of late medieval Europe, esoteric orders had been accused of using sexual rituals as part of their secret magical arts.33 However, perhaps the first evidence of a sophisticated use of sexual magical techniques appears in the mid-nineteenth century, with the mysterious figure of Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–75). Born to a wealthy Virginian father and a slave from Madagascar, Randolph was raised a poor, self-taught, free black in New York City. After running away from home at age sixteen, he traveled the world, wandering through Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. In the course of his travels, Randolph encountered a wide variety of esoteric traditions—not just European Spiritualist and Rosicrucian orders, but also a number of Sufi lineages. He claims to have derived much of his knowledge from a group of fakirs in the area of Jerusalem, which may have been a branch of the Muslim order of the Nusa’iri—a group long persecuted by orthodox Islam because of its alleged Gnostic sexual rituals.34 Eventually Randolph would emerge as one of the leading figures in nineteenth-century Spiritualism and the most famous scryer of his time.

However, Randolph is most famous as an exponent of spiritual eroticism, or Affectional Alchemy, a form of sexual magic that would have a profound impact on later Western esotericism. In sexual love, “he saw the greatest hope for the regeneration of the world, the key to personal fulfillment as well as social transformation and the basis of a non-repressive civilization.”35 For Randolph, orgasm is the critical moment in human consciousness and the key to magical power. It is the instant when life is infused from the divine realm into the material realm, as the soul is suddenly opened to the spiritual energies of the cosmos: “at the instant of intense mutual orgasm the souls of the partners are opened to the powers of the cosmos and anything then truly willed is accomplished.”36 As such, the experience of sexual climax has the potential to lead the soul either upward or downward, to higher states of transcendence or to depraved states of corruption: “The moment when a man discharges his seed—his essential self—into a . . . womb is the most solemn, energetic and powerful moment he can ever know on earth; if under the influence of mere lust it be done, the discharge is suicidal.”37 If one can harness the creative energy of orgasm, he or she can deploy it for a wide range of uses, to realize virtually any worldly or otherworldly goal. Not only can we achieve the spiritual aims of divine insight, but we can also attain physical health, financial success, or regain the passions of a straying lover.38

One of the most striking features of Randolph’s sexual magic, however, is his insistence that both male and female partners must have an active role in the process; in fact, both must achieve orgasm—ideally a simultaneous orgasm—for the magical operation to successful: “The woman’s orgasms should coincide with man’s emission, for only in this way will the magic be fulfilled.”39 The resulting pleasure that both partners feel in this union is nothing less than the overflowing joy of the divine emanating from above: “The joy. . . is diffused over both beings and each is based in the celestial and divine aura—the breath of God, suffusing both bodies, refreshing both souls!”40

Although Randolph seems to have no direct connection to Indian sexual practices, his teachings were to have a formative impact on later Western occult traditions, “releasing the genie” of sexual magic.41 And they would soon become mingled with the sexual traditions now being imported form the Orient, including the titillating erotica of the Kāma Sūtra and the esoteric mysteries of Tantra.

While it seems unlikely that Randolph had any knowledge of Tantra, it is more plausible that several later Western occultists did—in particular, the organizers of the highly esoteric movement of the Ordo Templi Orientis. Founded in the late nineteenth century by Karl Kellner (1861–1905) and Theodor Reuss (1855–1923), the OTO became the main conduit through which Western sexual magic began to merge with a (somewhat deformed) version of Indian Tantra. A wealthy Austrian chemist and industrialist, Kellner claims to have been initiated into Indian sexual techniques in the course of his Oriental travels, citing three masters—one Sufi and two yogis, one of whom may have been a Bengali tāntrika. Reuss, too, seems to have had some knowledge of left-hand Tantra, which he cites in his work.42 However, others suggest that Kellner’s inspiration may have been Randolph, whose sexual magic had been spread to Europe by a group of disciples in the late nineteenth century.43

Whatever their origins, much of the OTO ritual appears to have centered around the “inner kernel” of sexual magic—a quite different one from the more conservative system of Randolph. As the OTO proclaimed in 1912 in the Masonic journal Oriflamme:

One of the secrets which our order possesses in its highest grades is that it gives members the means to re-erect the temple of Solomon in men, to refind the lost Word. . . . Our Order possesses the Key which unlocks all Masonic and Hermetic secrets, it is the teaching of sexual magic and this teaching explains all the riddles of nature, all Masonic symbolism and all religious systems.44

The OTO developed a system of nine degrees (later expanded to eleven), the first six of which were more conventional Masonic initiations. The seventh, eight, and ninth, however, focused respectively upon the theory of sex magic and on the techniques of auto- and heterosexual magic. Homosexual intercourse also appears to have played a central role in the rituals.45 Through the magical act of intercourse, by focusing all of one’s will on a desired goal at the moment of orgasm, one can accomplish any occult operation, from the invocation of a god to the finding of hidden treasure. One may, for example, use these techniques to empower a talisman or another magical object: by focusing one’s will on the desired object during auto- or heterosexual orgasm, and afterward anointing that object with the semen, one can use the empowered object to achieve virtually any desired end. Similarly, the power of sex can be used to incarnate a god within one’s own consciousness, by concentrating on the deity at the moment of orgasm and so “blending their [man’s and god’s] personalities into one.”46

Surely the most infamous member of the OTO was the notorious magician and self-proclaimed “Great Beast 666,” Aleister Crowley (1875–1947; figure 12). Crowley’s practice is the clearest example of Western sexual magic combined (and perhaps hopelessly confused) with Indian Tantra. The son of a preacher in the puritanical Plymouth Brethren sect, Crowley is in many ways an exemplar of the Victorian age—raised in a prudishly repressive environment and turning later to extremes of sexual excess. Following Nietszche in his fierce rejection of Christianity as emasculated and weak, he “declared that all orthodox religions are rubbish and that the sole true gods are the sun and his vice-regent, the penis.”47 A poet, novelist, and accomplished mountain climber, Crowley would also become one of the most reviled characters of the twentieth century. Known in the press as “the wickedest man on earth,” Crowley was vilified as a “vicious Satanist who employed illicit drugs and perverted sex to enliven the weary charade of his blasphemous ‘magick.’”48 Much like Bernard’s infamy and scandals, Crowley’s were mostly about his sexual practices.

Figure 12. Aleister Crowley, costumed as an Eastern sage for a publicity photo to attract students (ca. 1936). Courtesy of Ordo Templi Orientis, Berlin.

His most recent biographer, Lawrence Sutin, suggests that Crowley may have first learned Tantric practices in Ceylon as early as 1901, while studying Buddhism; yet he seems to have been initially quite repulsed by them, dismissing them as “follies of Vamacharya (debauchery).”49 His attitudes toward such rituals appear to have changed in the next few years, however, when he began to experiment in his own sexual magic. Already in 1902, Crowley and his partner Rose had begun to engage in a series of “secret rites, of a sexual nature (and related to Tantric practices, such as the emulation of the passive Shiva in cosmic coupling with the mounted energetic Shakti).”50 Other authors think Crowley may have been even more deeply involved in left-hand Tantric rites during his travels in India. We have already considered Elizabeth Sharpe’s semifictional account Secrets of the Kaula Circle, which describes a mysterious Englishman calling himself by the number 666. Once handsome, but later gross, 666 uses various magical processes, pentangles, and swords to draw phantoms into his circles with the help of Tantric lamas; yet he later falls to the ground frothing at the mouth, the victim of his own decadent black magic. Nik Douglas concludes that this is clearly a reference to Crowley and provides evidence that he had extensive knowledge of Tantra (though it seems equally likely that Sharpe has worked the infamous Beast 666 as a fictional character into her narrative).51

Yet whatever their origin, sexual practices clearly formed an integral part of Crowley’s magical repertoire. “Sex is a sacrament,” as the Great Beast put it in his Book of Lies. These practices became particularly central during the years of his involvement with the OTO. After reading his Book of Lies in 1912, Theodor Reuss allegedly contacted Crowley and accused him of revealing the innermost secret of the OTO: the secret of sexual magic. Though Crowley had done so unintentionally, the story goes, he was named the Sovereign Grand Master General of Ireland, Ioana, and all the Britains. In his Confessions, Crowley discusses the nine degrees of the OTO’s initiations, together with the two he later added, and also points to the kernel of sexual magic at the center of the higher degrees:

If this secret [of sexual magic] which is a scientific secret were perfectly understood, as it is not by me after more than twelve years’ almost constant study and experiment, there would be nothing which the human imagination can conceive that could not be realized in practice. . . . If it were desired to have an element of atomic weight six times that of uranium that element could be produced.52

Thus in his magical rites, Crowley calls not for any ascetic withdrawal or denial of the flesh, but rather for the fullest celebration of the body, with all its desires, in the ceremony of love:

Then comes the call of the Great Goddess, Nuit, Lady of the Starry Heaven. . . . “Come forth, O children under the stars and take your fill of love! I am above you and in you. My ecstasy is in yours. . . . Is ours the gloomy asceticism of the Christian . . . ? Are we walking in eternal fear lest some ‘sin’ should cut us off from ‘grace’? By no means. . . . Dress ye all in fine apparel, eat rich foods and drink sweet wines that foam! Also take your fill of and will of love as ye will when, where and with whom ye will!”53

Crowley’s most intense period of experimentation in sexual magic appears to have begun in 1914, during his “Paris workings.” Together with his homosexual lover, the poet Victor Neuberg, Crowley engaged in a variety of sexual rites intended to achieve both spiritual and material ends—both the primary goal of “invoking the gods Jupiter and Mercury and the secondary one of getting these gods to supply Crowley and Neuberg with money.”54 As Julius Evola suggests, Crowley saw in orgasm (as in drug experience) a means to create “openings or breakages of consciousness” that give the soul access to supersensual and ecstatic states.55 However, as others point out, Crowley was perhaps more often concerned with the efficacy of sexual techniques for “obtaining wealth or anything else the magician might desire.”56 For example, Crowley suggests that one might use sexual magic to “perform an operation to have $20,000.” By totally focusing one’s will upon an object at the moment of orgasm, one can powerfully influence the course of events and achieve the desired goal: “The purpose of these operations of High Magick Art was to obtain priestly power and, on a lower plane, money.”57

However, the ultimate goal that Crowley sought through his sexual magical practices seems to have gone far beyond the mundane desire for material wealth; in his most exalted moments, Crowley believed that he could achieve the birth of a divine child—a spiritual, immortal, godlike being, who would transcend the moral failings of the body born of mere woman. This goal of creating an inner immortal fetus, Crowley suggests, lies at the heart of many esoteric traditions, from ancient Mesopotamia to India to the Arab world:

This is the great idea of magicians in all times—To obtain a Messiah by some adaptation of the sexual process. In Assyria they tried incest . . . Greeks and Syrians mostly bestiality. This idea came from India. . . . The Mohammedans tried homosexuality; medieval philosophers tried to produce homunculi by making chemical experiments with semen. But the root idea is that any form of procreation other than normal is likely to produce results of a magical character.58

Now, if it is possible that Crowley had some contact with Indian Tantra and drew some of his sexual practice from Eastern sources, it would seem that he also creatively reinterpreted them through his own occult system. Much of Crowley’s magic, for example, involved homosexual intercourse—something almost never found in Tantric rituals. More importantly, Crowley was not content simply to achieve a spiritual union of the divine male and female principles; rather, he sought nothing less than the conception of a magical fetus or spiritual child—a kind of golem like that of the Kabbalistic and alchemical tradition:

The principal difference between Crowley’s sexual magic and traditional Tantric techniques now becomes clear. For Crowley, the object of the ritual was not limited to mystic union with the goddess . . . but could further involve the creation of a new spiritual form—a magical child. . . . This magical child could be . . . any form of concentrated inspiration, or it could manifest physically as a talisman or even within a human being—as in a newborn baby or a newly spiritually transformed adult man.59

Thus, we might say that the magical and sexual career of Aleister Crowley was in many ways parallel to that of Pierre Arnold Bernard. In fact, the two briefly met. Not only do many of Crowley’s teachings seem to bear some resemblance to those of Bernard’s American Tantra, but it would seem that Crowley also had direct contact with the members of the Tantrik Order in the 1920s. Crowley was first introduced to his infamous “Scarlet woman,” Leah Hirsig, in New York in 1918 by her sister Alma, who was an ardent disciple of Bernard in his Tantrik Order in New York. Alma would later publish her expose of Bernard’s group, under the pseudonym of Marion Dockerill, entitled My Life in a Love Cult: A Warning to All Young Girls (1928). As Sutin observes, “There are . . . obvious parallels in the paths of Alma as High Priestess and Leah as Scarlet Woman.”60 This parallel between the sister-consorts of Crowley and Bernard is quite fitting: after all, both Crowley and Bernard were to become notorious in the American popular imagination as high priests of secret Tantric rituals; and both would soon face intense scandal and media attack, largely because of their illicit sexual practices.

Crowley and Bernard were instrumental in three ways in the transmission and transformation of Tantra in the West. First, they were both key figures in the sensationalization of Tantra in the popular imagination, as it became an increasing object of scandal and media exploitation during the early twentieth century. Second, both were key figures in the reinterpretation of Tantra, as it was transformed from a tradition concerned primarily with secrecy and power to one focused on the optimization of sexual orgasm. Finally, the combined influence of Crowley and Bernard led to the increasing fusion of Western esoteric traditions with Indian Tantra. Today, one need only browse the shelves of any New Age bookstore to find a range of magazines, videos, and texts bearing titles like Tantra without Tears; Sex, Magic, Tantra, and Tarot; and Secrets of Western Tantra—most of which are based on the fundamental equation of Indian Tantric techniques and Crowleyian-style sexual magic.61

Tantra is . . . not withdrawal from life but the fullest possible acceptance of one’s desires, feelings and situations as a human being. . . . Explore the fascination of desire, love and lust to its limit. . . . Thus the follower of the Tantric way plunges himself into just those things which the ascetic renounces: sexuality, food and drink, and all the involvements of worldly life.

Alan Watts, “Tantra” (1976)

Although Tantra had begun to emerge in the early twentieth century as something scandalous, shocking, and yet also terribly interesting, it didn’t burst into popular culture as a full-blown “cult of ecstasy” or “yoga of sex” until the 1960s. Now mingled with the erotica of the Kāma Sūtra, Pierre Bernard’s sex scandals, and the magick of the Great Beast 666, Tantra fit in nicely with the American counterculture and the so-called sexual revolution. As critics like Jeffrey Weeks and others argue, the period of the 1960s and 1970s represent something more complex than a simple liberation of the Western libido from its prudish Victorian shackles; for the freedom of sex in the age of promiscuity also came with all sorts of new oppressions and bonds. Nonetheless, it seems clear that this period witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of discussion and debate about sex, along with new fears about the growing promiscuity among young people. “Violence, drugs and sex, three major preoccupations of the 1960s and 70s blended symbolically in the image of youth in revolt.”62

The literature on Tantra was a key element in this new proliferation of discourse about sexual freedom. Thus, in 1964, we see the publication of Omar Garrison’s widely read Tantra: The Yoga of Sex, which advocates Tantric techniques as the surest means to achieve extended orgasm and optimal sexual pleasure: “Through . . . the principles of Tantra Yoga, man can achieve the sexual potency which enables him to extend the ecstasy crowning sexual union for an hour or more, rather than the brief seconds he now knows.” Fighting against the repressive prudery of Christianity, which has for centuries “equated sex with sin,” Garrison sees in Tantra a much needed cure for the Western world, bearing with it “the discovery that sexual union . . . can open the way to a new dimension in life.”63 As one contemporary Tantric teacher observes, “The radical no-nonsense nature of Tantric teachings made them very attractive to the sixties generation. Psychedelic mind-expanding drugs, uninhibited sex, and the quest for spiritual experiences took on new meaning. . . . Tantra helped legitimize the sixties experience, helped give it spiritual and political meaning.”64

At the same time, Tantra began to enter into the Western popular imagination in a huge way, as entertainers, musicians, and poets began to take an active interest in this exotic brand of Eastern spirituality. This process had already begun with the Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, who saw Tantra as a means of breaking through the repressive morality of middle-class American society. One of the first hippies to journey to India in search of enlightenment, intense spiritual experiences, and/or cheap drugs, Ginsberg would later become a disciple of Chogyam Trungpa’s radical brand of Tantric Buddhism. Tantra is for Ginsberg categorized with other methods of “organized experiment in consciousness,” such as “jazz ecstasy” and drugs as a means of altering mental states and achieving “increased depth of perception on the nonverbal-nonconceptual level.”65 For Ginsberg, India represents the complete opposite of modern America: whereas America is sexually repressed, uptight, and overly rational, India is the land of unrepressed, spontaneous sexuality. And Tantric sexuality, embodied in the violent, terrifying goddess Kālī, is a liberating alternative to the oppressive prudery of Cold War America:

Fuck all Hindu Goddesses

Because they are all prostitutes

[I like to fuck]

. . . . . . .

Fuck Ma Kali

Mary is not a prostitute because

She was a virgin

Christians don’t

Worship prostitutes

Like the Hindus.66

Not only is Kālī an intense image of sexual liberation, but she also serves as a powerful political symbol. In a wonderfully ironic use of images, Ginsberg superimposes the terrible mother Kālī onto the figure of the Statue of Liberty, combining the violently sexual Tantric goddess with the icon of American identity. In the Beat poet’s inverted vision, the skulls around Kālī’s neck become the world’s great leaders—American presidents, fascist dictators, and Soviet leaders alike—while the Terrible Mother stands atop the prostrate corpse of Uncle Sam:

The skulls that hang on Kali’s neck, Geo Washington with eyes rolled up & tongue hanging out of his mouth like a fish, N. Lenin upside down, Einstein’s hairy white cranium. Hitler with his mustache . . . Roosevelt with grey eyeballs; Stalin grinning; Mussolini with a broken jaw . . . Mao Tze Tung & Chang Kai Shek shaking at the bottom of the chain, balls with eyes and noses jiggled in the Cosmic Dance. . . . A huge bottomless throat and a great roar of machinery chewing on these Hydrogen Bombs like bubble gums & bursting all over its mouth as big as the Lincoln Memorial. . . . The Vajra Hand balancing a high Rolls Royce on end, fenders sticking up into the empty night heavens—battleships dangling from an arm. . . .

Her foot is standing on the godlike corpse of Uncle Sam who’s crushing down John Bull, bloated himself over the Holy Roman Emperor & Mohammed’s illiterate belly.67

In sum, for Ginsberg and other voices of the American counterculture, Tantric imagery is turned into a powerful weapon to criticize the dominant sociopolitical order, which is perceived as repressive, bankrupt, and corrupt. With its emphasis on the terrible, erotic Mother Kālī, Tantra seemed to offer a much needed antidote to a hypercerebral Western world that had lost touch with the powers of sex, femininity, and darkness. In the words of Alan Watts, an ex-Anglican priest who became a Zen master and a psychedelic guru of the Beat generation,

Tantra is therefore a marvelous and welcome corrective to certain excesses of Western civilization. We over-accentuate the positive, think of the negative as “bad” and thus live in a frantic terror . . . which renders us incapable of “playing” life with an air of . . . joyous detachment. . . . But through understanding the creative power of the female, the negative . . . we may at last become completely alive in the present.68

To all those Tantra souls of the New Age who are leading the world into a Kingdom of perfect love.

Dedication in Howard Zitko, New Age Tantra Yoga (1974)

By the 1970s, this American version of Tantra would become one of the most important elements in the proliferation of a new wave of alternative religious movements, collectively known, ratherly vaguely, as New Age—a category that is, of course, every bit as amorphous and polyvalent as “Tantra” itself. Most often, “New Age” refers to an enormous heterogeneity of different spiritual movements, lifestyles, and consumer products—“a blend of pagan religions, Eastern philosophies and occultpsychic phenomena,” drawn from “the Euro-American metaphysical tradition and the counterculture of the 1960s.”69 Yet as Paul Heelas has recently argued, beneath the tremendous diversity, there are some basic unifying themes that pervade the many phenomena we label New Age. Above all, he suggests, the dominant tropes include “the celebration of the Self and the sacralization of Modernity”—that is, the fundamental belief in the inherent divinity of the individual self and an affirmation of many basic values of Western modernity, such as “freedom, authenticity, self-responsibility, self-reliance, self determinism, equality, and above all the self as a value in and of itself.”70

In more recent years, there has been a growing movement within the New Age toward a sanctification, not only of the self and modernity, but also of material prosperity, financial success, and capitalism. In contrast to the 1960s countercultural rejection of materialism, more recent New Agers have shifted to an affirmation of material wealth, searching for a harmonious union of spirituality and prosperity, religious transcendence and success in capitalist business: “God is unlimited. Shopping can be unlimited,” according to Sondra Ray, best selling author of How to Be Chic, Fabulous, and Live Forever.71 Since at least the early 1970s, this “world-affirming” side of the New Age had begun to emerge in movements like EST, Scientology, and the Human Potential Movement; and it came into full bloom during the power generation of the 1980s, with Shirley MacLaine, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and a wide array of gurus promoting the union of spirituality and financial success through books and videos such as Money Is My Friend or Prosperity Consciousness. For this more worldly side of the New Age, “the more spiritual you are the more you deserve prosperity,” for “being wealthy is a function of enlightenment.”72 The “New Age” has itself become a highly marketable phenomenon, a catch-all label with which to sell a vast array of consumer products: books, videos, health foods, diet supplements, crystals, incense, clothing, ritual implements, workshops, classes, seminars, and so on. As Heelas comments, “Today. . . we have New Age leaders praising capitalism and teaching that it is fine to work and succeed within the system . . . teaching that there is nothing wrong with materialistic consumption . . . and providing training to engage managerial efficacy.”73

It is hardly surprising that many New Age practitioners have turned to Tantra—a form of spirituality that seemingly affirms the essential divinity of the human self and seeks the union of sensuality with spirituality, material enjoyment with otherworldly bliss. No longer imagined as the religion for the age of darkness, Tantra has reemerged as one of the most powerful “religions for the Age of Aquarius.” For it seems to embody both the countercultural revolt against prevailing Christian values and the celebration of the body and sensual ecstasy. Now mingled with various occult movements like Crowleyian sex magic and traced back to ancient Egypt and the lost city of Atlantis, Tantra has entered fully into the Western imagination:

Tantra, the dual yoga of sexual rejuvenation by spiritual ritual . . . has been suppressed, censored and ridiculed. . . . This is the period of history wherein . . . nothing shall be hidden; all shall be known. It is in this spirit of revelation that this work is added to that growing number which is opening the New Age to whosoever will contemplate the future of Mankind Two, the inheritors of the New World . . . of the 21st century.74

For many of this generation, the Tantric wedding of spirituality with sensuality, otherworldly transcendence with this-worldly ecstasy, seemed to represent the very essence of the dawning Age of Aquarius. But Tantra would also undergo some changes in the course of its rebirth: no longer a dangerous esoteric cult centered on transgressive power, Tantra has reemerged as a life-affirming, celebratory, “pop religion,” a sensual spirituality for the masses:

As the New Age manifested, traditional Tantra was transformed into a Tantra for the masses, a neo-Tantric cult of sensual pleasure with a spiritual flavor. . . . In the 21st century Tantra will . . . bless those prepared to deal with the new spiritual reality . . . in the flowering of the Age of Aquarius which commenced in 1962.75

One of the most interesting developments in the rise of this “New Age Tantra” has been Nik Douglas’s revival of Pierre Bernard’s Tantrik Order. Now promoting the “New Tantric Order in America,” Douglas has created a revised version of the Omnipotent Oom’s Westernized spiritual sex, reconstituted for a new millennium. Offering online initiations into the “secret” teachings of his New Tantric Order, Douglas has drafted an “Updated New Tantric Order Document” (1996), which brings Bernard’s own 1906 document more in line with contemporary American concerns: “TantraWorks (tm) offers membership in the ‘New Tantric Order,’ which will offer participants the opportunity to advance through personalized Tantra initiations and allow access to all the Tantra databases on this Web Site.”76 For Douglas, Tantra is now a movement of truly revolutionary potential, one that will reunite the realms of sex and spirit, so long dichotomized by the Western mind:

It’s wondrous, exhilarating and true; you can use sexual pleasure as a guide to spiritual fulfillment. Not only is the sensual path enriching and joyful, but it’s delightfully accessible with Tantra. . . . A revolutionary movement sure to be a watershed . . . in the coming millennium, spiritual sex celebrates the mystical aspects of sexuality while revealing the secrets that allow men and women to reach a zenith of ecstasy.77

Rather significantly, Douglas’s New Tantric Order does not seem to have generated any of the scandal or moral outrage that surrounded Bernard’s original Tantrik Order; on the contrary, its brand of sacred sexuality seems to be remarkably at home in American consumer culture at the start of the millennium.

People are suffering from a wound. Sex has become a wound; it needs to be healed.

Osho,

Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic (2000)Tantra has thus far been glimpsed in the West only in its most vulgar and debased forms, promulgated by unscrupulous scoundrels who equate sex with superconsciousness.

Robert E. Svoboda,

Aghora: At the Left Hand of God (1986)

Tantra, it would seem, has undergone a series of transformations in the course of its tangled journey to the West. Most importantly, we can see two phenomena at play in the transmission of Tantra to America and its embrace by the New Age. The first is the more or less complete identification of Tantra with “sacred sex.” Tantra has increasingly been associated and often hopelessly confused, not only with the Indian erotic arts like those of the Kāma Sūtra, but also with Western erotic-occult practices like those of Crowley and the OTO. In the process, the focus has shifted more and more to the power of sexual orgasm as the essence of Tantric magic. As we read, for example, in Christopher Hyatt’s Secrets of Western Tantra, “Unlike most forms of Tantric practice, orgasm is not only allowed but essential to create the desired results. . . . Many forms of Tantra are restricting . . . focusing on holding back. . . . Western Tantra is completely different. . . . [C]omplete Orgasm is freeing and energizing.”78

The second phenomenon is the appropriation of Tantra in this larger narrative of “liberation.” By the end of the twentieth century, Tantra had come to be synonymous with freedom on every level—sexual, spiritual, social, and political. According to a common narrative, repeated throughout New Age and alternative spiritual literature, our natural sexual instincts have long been repressed by the distorted morality of Western society and Christianity. “For centuries organized religions have used guilt about sex as a subtle way of exploiting people and the recent liberalization of sexuality has not yet succeeded in erasing this cruel legacy.”79 Thus, Tantra is the most needed spiritual path for our age, the means to liberate our repressed sexuality and reintegrate our physical and spiritual selves: “Sexual liberation implies the liberation of the whole being: body, mind and spirit.”80

Not surprisingly, Tantra has been taken up in the service of a variety of calls for social and sexual liberation. Since at least the 1970s, the aggressive Tantric goddesses Śakti and Kālī have been appropriated by a number of feminists in search of a radical symbol of empowerment. Thus we find the rise of the “Shakti woman,” with her “new female shamanism,” along with the birth of the “Erotic Champion,” holding a power that “far exceeds the claims of any woman’s liberation movement.”81 More recently, the seemingly quite heterosexual practices of Tantra also have been adapted in the service of gay and lesbian calls to liberation. Like the sexual secrets of Tantra, many gay-rights advocates claim, homosexuality has been suppressed by Western religion for two millennia, and Tantra can be employed as a tool for their liberation as well.82

Yet both of these imaginings of Tantra—as sex magic and as liberation—would seem to have much less to do with any particular Indian tradition than they do with the peculiar obsessions, fantasies, and repressed desires of the modern West. It is, I would argue, an extreme example of the larger role of sexuality in contemporary Western culture. As Foucault observes, it may not be entirely true that we in the modern West have “liberated” sexuality in some radical way; but it does seem that our generation has taken sex to the furthest possible extremes—to extremes of transgression and excess, not resting until we have shattered every law, violated every taboo: “We have not in the least liberated sexuality, though we have . . . carried it to its limits: the limit of consciousness, because it ultimately dictates the only possible reading of our unconscious; the limit of the law, since it seems the sole substance of universal taboos.”83 It is precisely this relentless search for the limit that seems to drive the characteristically American style of Tantra.

Of all emotions man suffers from, . . . sex and sex-oriented emotions demand the most vital sacrifice. It is the most demanding . . . of emotions; it is also the most self-centered. . . . It adores the self most and hates to share its joy and consummation. It is wanted the most; it is regretted the most. It is creative, it is destructive. It is joy; it is sorrow. Bow to sex, the hlādinī [the power of delight].

Brajamadhava Bhattacharya, The World of Tantra (1988)

The sex act has more names in America than anything else. . . . The problem is that not only are they obsessed with sex, they’re making the rest of the world equally crazy.

Anurag Mathur, The Inscrutable Americans (1999)

If Swami Vivekananda worked hard to cover over the Tantric nature of his master’s teachings, and even wholly to censor this dimension of the Hindu tradition, a variety of new gurus arrived in America in the 1970s who would do just the opposite. Beginning with the notorious neo-Tantric masters Osho-Rajneesh and Chogyam Trungpa, a number of Hindu and Buddhist teachers would make the journey to the West, openly proclaiming Tantra as the most powerful means to liberation. At the same time, these Tantric masters have been influenced by Western ideas and obsessions—perhaps above all, the preoccupation with sex and its liberation. “Sex has become an obsession, a disease, a perversion,” as Rajneesh observed in 1971.84 Indian gurus, too, seem to have accepted the identification of Tantra with sex and to have taught a largely “sexo-centric” brand of Tantra marketed as the most exciting path to enlightenment. As such, they are powerful examples of the feedback loop between East and West, as Tantra has been exported, imported, and reexported for a new age of consumers.

Many people in America have heard about Tantra as the “sudden path”—the quick way to enlightenment. . . . Exotic ideas about Tantra are not just misconceptions; they could be destructive. It is dangerous . . . to practice Tantra without establishing a firm ground in Buddhist teachings.

Chogyam Trungpa, Journey without Goal (1985)

All the monsters of the Tibetan Book of the Dead might come out and get everybody to take LSD! . . . The Pandora’s Box of the Bardo Thodol has been opened by the arrival in America of one of the masters of the secrets of the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Allen Ginsberg, quoted in Barry Miles, Allen Ginsberg (1989)

Born in Tibet in 1939 and dying in the United States fifty years later, Chogyam Trungpa stands out as one of the most controversial Tantric gurus in the late twentieth century. As he recounts in his autobiography, Trungpa led an amazing life of adventure, tragedy, fame, and scandal.85 Born in a small tent village in the Tibetan mountains, he was identified by Buddhist monks at eighteen months as the reincarnation of the abbot of Surmang monastery. Thus named the eleventh Trungpa of the Karma Kargyupa tradition, he took monastic vows at age eight and led a rigorous life of study, meditative discipline, and ritual practice. In 1959, he fled the new communist regime, leading three hundred Tibetans through the mountains to refuge in India. Having taught himself English, he traveled to Oxford in 1963. Finally, after being injured in a car accident and paralyzed on his left side, he came to the United States in 1970, at the height of the countercultural revolution’s search for alternative realities through drugs, Eastern mysticism, and other intense psychic or physical experiences.

When he arrived, however, Trungpa was far from what most Americans expected in a Tibetan lama. Caring little for asceticism, Trungpa dressed and lived lavishly, freely partaking of food, alcohol, drugs, and the pleasures of a wealthy life. He was known for wearing expensive suits, riding in a chauffeured Mercedes, retaining servants, and living in the finest suites of expensive hotels. “He ate what he liked, consumed any quantity of alcohol, smoked and freely joined . . . ingesting psychedelics. . . . He understood his own crazy-wise conduct as a counter-point to the widespread disease of spiritual materialism.”86

Nonetheless, this behavior did not prevent Trungpa from establishing a large and powerful following of eager American adepts in Boulder, Colorado, where he founded the Naropa Institute in the 1970s.87 A Mecca for alternative spirituality and new meldings of Eastern and Western thought, Naropa quickly attracted a wide array of dropouts, hippies, and students, and a number well-known poets, musicians, and countercultural leaders, like Alan Watts, W. S. Merwin, Gregory Bateson, and Agehananda Bharati. Trungpa’s American disciples appear not to have been repulsed by, but rather to have relished his bizarre and erratic behavior, worshiping Trungpa as the ideal crazy-wisdom guru who could shock them out of their comfort and complacency in the bourgeois capitalist West. Acting in a consistently unpredictable and incorrigible manner, Trungpa was regularly late for his own lectures, often arriving inebriated and sometimes downing a few beers in the course of his teachings. “During meditation he was occasionally seen to nod off, but on other occasions he would sneak up on unsuspecting meditators to squirt water at them with a toy pistol.”88 In order to shock his disciples out of their “spiritual materialism”—that is, the overattachment to religion, which the ego tends to turn into yet another object of pride—Trungpa would break up his meditations with raucous parties, bouts of drunken abandon, or orgies. “Trungpa had disciples carry him around naked at a party, broke antennas off cars . . . spent days speaking in spoonerisms. Assuming that the ego . . . will subvert any material it is given . . . these masters attempt to wake people through extreme behavior which challenges their everyday behavior.”89

All this seeming hedonism and madness, Trungpa explained, was only part of his radical and direct spiritual method. His was the way of the Tiger—a quick, direct, but also dangerous and potentially deadly path to liberation:

Here comes Chogyam disguised as a hailstorm no one can confront him

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

He cannot be defeated

Chogyam is a tiger with whiskers and a confident smile

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

He escaped from the jaws of the lion.90

This tiger-guru was therefore not afraid of using the most violent and shocking tactics to liberate his disciples. Anything is permissible for the guru, as long as it is for the ultimate good of his devotee: “What if you feel the necessity for a violent act in order ultimately to do good for a person? You just do it.”91

This, for Trungpa, is the very essence of Tantra. As the lightning-bolt path, Tantra is both the quickest and the deadliest, the easiest and the most easily abused of spiritual means: it is a path that attempts, not to repress the lower impulses of passion, sensuality, and violence, but to harness these darker energies as the most potent fuel propelling us to liberation: “Passion, aggression and ignorance, the source of human suffering, are also the wellspring of enlightenment. . . . They can be transformed into Buddha-mind.”92 On the Vajrayāna path, one must attempt to drink the poison of desire and to transform it into divinizing ambrosia. And perhaps most potent of all is the energy of sexual desire:

In Trungpa’s teaching style, sexual passion was accepted as a reflection of our basic goodness and could be a way of experiencing enlightenment. His favorite metaphor for giving in to the dharma was having an orgasm. “You just do it . . . all at once.” He referred to arousing bodhicitta as tickling the clitoris of the heart. . . . Trungpa and Tendzin were both notorious for the number of their sexual partners or consorts.93

Not surprisingly the Tantric path is also a potentially deadly one—a path demanding that the disciple surrender his entire self to the power of the guru, who alone can guide him through this dangerous ordeal: “working with the energy of Vajrayāna is like working with a live electric wire,” he warns. “It is better not to get into Tantra, but if we must get into it, we had better surrender. . . . We surrender to the fact that we cannot hold on to our ego.”94 The guru must be accepted as the absolute, unquestioned authority, and in fact as the supreme deity who will shatter the false ego of the disciple and lead him or her to liberation. As Trungpa put it in one lecture to his students, “Thank you for accepting me as your friend, teacher, dictator.” And as Butterfield reflects on his own experience,

Trungpa . . . seemed bent on stoking the agony by acting so bizarre that I wondered if he was capable of ordering us all to commit suicide. On the night of the Vajrayana transmission he rambled from subject to subject in a series of blazing non sequiturs . . . waited until we were dozing off and then shouted “Fat!” or “Fuck You!” into the microphone loud enough to burst our eardrums.95

When we look more closely at the complex history of Trungpa’s following in Boulder, however, we might begin to wonder whether he heeded his own advice as to the danger of his Tantric teachings. For the history of his life and community is a disturbing story of turmoil, emotional violence, and scandal. Trungpa’s socially objectionable behavior had begun to be made public as early as 1975, when a poet, W. S. Merwin, and his wife attended an intensive three-month seminar with Trungpa. At the beginning of the course on Vajrayāna Buddhism, Trungpa suddenly interrupted the seminar with a raucous Halloween party. Arriving quite late and intoxicated, Trungpa began to ask people to undress, then took off his own clothes and had himself carried around naked on the shoulders of his students. Merwin and his wife soon decided that the party had gotten out of control and went to their rooms to pack their bags. When the couple repeatedly refused Trungpa’s order that they join the party, locking themselves inside their room, a band of drunken disciples kicked in their windows and dragged them forcibly before the master. Trungpa then proceeded to insult Merwin’s Oriental wife with racist remarks, threw a glass of sake in the poet’s face, and had the pair stripped in front of everyone. One student was apparently courageous enough to oppose the mob mentality, but his pleading was rewarded only by a punch in the face from Trungpa.96

Even more disturbing events surrounded Trungpa’s American disciple Thomas Rich, renamed Osel Tendzin, who was appointed his successor in 1976. An alcoholic like Trungpa, Tendzin was also known to have had sexual relations with female students—even after he was diagnosed with AIDS, and so infected at least one of his many disciple-lovers with the virus. As such, Butterfield suggests, he is a striking embodiment of the very real danger of the spiritual “poison” of the Tantric path: “The Tantric Buddhist way of handling passion may lead to disaster . . . no matter how great a master we become the danger never disappears.”97

Most of this shocking and outrageous behavior, however, was not mentioned by Trungpa’s disciples. In accordance with the Tantric injunction to keep such powerful, dangerous, potentially misunderstood teachings hidden from the eyes of the masses, such events were kept strictly secret among the inner circle of closest initiates.

To be part of Trungpa’s inner circle you had to take a vow never to reveal . . . some of the things he did. This co-personal secrecy is common with gurus. . . . It is also common in the dysfunctional family systems of alcoholics and sexual abusers. The inner circle puts up an almost insurmountable barrier to a healthily skeptical mind.98

As Butterfield reflects on his own experience with Trungpa’s radical brand of Tantra, it was indeed, as the master had often said, much like the experience of sexual intercourse—an intense, shocking, yet also potentially damaging and emotionally crippling encounter: “It was like jumping from a cliff into a quarry pool. . . . You just do it, he said, ‘like having an orgasm’—an image that had uncomfortable associations with getting screwed.”99

Rather remarkably, in the years since his death, Trungpa’s scandalous crazy-wisdom tactics appear to have been forgiven and largely forgotten by most of his disciples. Many see his radical behavior and controversial teachings as a part of his “skillful means” (upāya). Thus Allen Ginsberg defended Trungpa as one of those great spiritual masters, who, like the radical poets of the 1960s and 1970s, had the “right to shit on anybody they wanted to. . . . Burroughs commits murder, Gregory Corso . . . shoots up drugs for twenty years . . . but poor old Trungpa, who has been suffering since he was two years old to teach the dharma, isn’t allowed to wave his frankfurter.” Trungpa’s crazy-wisdom tactics, even his alcoholism and sexual misconduct, were but so many skillful “tricks” designed to jolt his deluded, brain-dead disciples into awakening.100 Today, Trungpa is still venerated as one of the greatest pioneers in the transmission of Buddhism to America and one of the most innovative masters of Tantra in the last century.

Tantra is a dangerous philosophy, it is a dangerous religion. It has not yet been tried on a larger scale, man has not yet been courageous enough to try it on a larger scale because the society does not allow it. . . . [T]he society thinks this is absolute sin. . . . Tantra believes in joy because joy is God.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, The Tantric Transformation (1978)

I sell happiness. I sell enlightenment.

Rajneesh, interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes (1985)

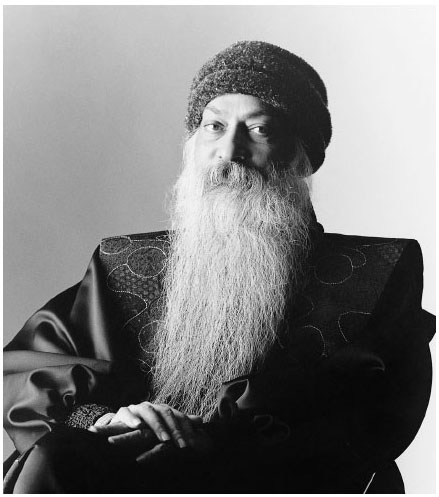

The second American Tantric guru I want to examine here is one who represents a good complement, comparative contrast, and striking juxtaposition to Dr. Pierre Bernard—namely, the infamous sex guru and guru of the rich known in his early years as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and in his later life simply as Osho (figure 13). If Bernard was among the first Americans to travel to India and bring Tantra to this country, Osho-Rajneesh was one of the first Indians to travel to America and import his own brand of “neo-Tantrism,” marketed to late-twentieth-century American consumer culture. Whereas Bernard’s version of Tantra represents a kind of sexualization and scandalization of Tantra, Osho-Rajneesh’s version is a commodification and commercialization of the tradition.

Figure 13. Osho in Poona, 1988. Copyright © Osho International Foundation, www.osho.com.