‘Let this duncified worlde esteeme of Spenser and Chaucer, I’le worship

sweet Mr. Shakespere.’

—The Return from Parnassus, Part 1 (1600)1

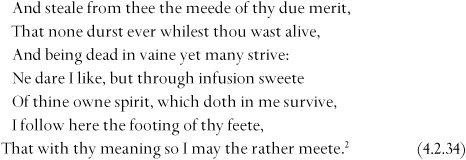

To specify the connection between Shakespeare and the Middle Ages, we might turn to one of the defining medieval moments of the Elizabethan era. In Book 4, canto 2, of the 1596 Faerie Queene, England’s New Poet, Edmund Spenser, pronounces himself the national heir to the Old Poet, ‘Dan Chaucer, well of English undefiled’ (4.2.32):

Then pardon, O most sacred happie spirit,

That I thy labours lost may thus revive,

In this self-conscious apostrophe to a ‘dead’ author, Spenser identifies the principle by which he will ‘revive’ Chaucer’s ‘labours lost’—a principle he calls ‘infusion’. Through the ‘sweete’ process of infusion, he will mystically receive the surviving ‘spirit’ of Chaucer, and through this transfer of spiritual power he will ‘follow’ the ‘footing’ of the old poet’s ‘feete’, so that he can ‘meete’ Chaucer’s ‘meaning’ and thus continue his immortalizing fame.3

Moreover, according to the New Poet, the principle of infusion differs from other principles of literary relation being used at that time to claim status as Chaucer’s heir. During Chaucer’s lifetime, Spenser says, no one could ‘meete’ Chaucer, even though after the great poet’s death ‘many’ ‘strive’ in ‘vaine’. The word ‘strive’ presumably refers to a process of futile labor unauthorized by Chaucer himself, who consents only to transfer his surviving inner form effortlessly and sweetly to Edmund Spenser. As Craig A. Berry points out, Spenser ‘replaces filiation as begetting with filiation as spiritual infusion—a more flexible, and thus, safer imitative strategy for a poet who wants to be identified with a famous predecessor for support in facing a potentially doubting audience—but at the same time finds it necessary to distance himself from some of that predecessor’s dubious associations.’4

Contemporaries immediately recognized Spenser as the heir of Chaucer, interpreting the genealogy as a triumphal moment of literary succession. In the words of Thomas Speght from his 1598 edition of Chaucer,

In his Faerie Queene in his discourse of friendship, as thinking himself most worthy to be Chaucers friend, for his like naturall disposition that Chaucer had, hee sheweth that none that lived with him, nor none that came after him, durst presume to revive Chaucers lost labours in that unperfite tale of the Squire, but only himself: which he had not done, had he not felt (as he saith) the infusion of Chaucers owne sweet spirite, surviving within him.5

Repeatedly during Shakespeare’s lifetime, contemporaries linked the New with the Old Poet, from Gabriel Harvey in 1580–93 (49, 50, 55), William Camden in 1600 (114), I.F. also in 1600 (105), Charles Fitzgeoffrey in 1601 (109, 111), and Michael Drayton in 1605 (79), to William Warner in 1606 (113), Thomas Dekker in 1607 (122), Thomas Norden in 1614 (130), and Ben Jonson in 1616 (135). According to Dekker, ‘Grave Spencer was no sooner entred into this Chappell of Apollo, but these elder Fathers of the Divine Furie, gave him a Lawrer & sung his Welcome: Chaucer call’de him his Sonne, and plac’de him at his right hand’ (122). Effectively, Dekker replaces Spenser’s principle of ‘filiation as infusion’ with the more familiar principle of ‘filiation as begetting’. Spenser’s inheritance of the title ‘English National Poet’ from Chaucer remains one of our most durable authorial genealogies, as testified to by the voluminous commentary in the centuries following.6

Yet the epigraph to the present essay intimates something else—something not charted by recent criticism. Around the turn from the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries, writers began to link Shakespeare with Spenser, to place Shakespeare in the company of both the Old and the New Poet, and to see Shakespeare as the successor to both.7 In the 1600 Return from Parnassus, Part 1, the anonymous Cambridge University authors present a character named Gull choosing to let ‘this duncified worlde esteeme of Spenser and Chaucer’, while he ‘worship[s] sweet Mr. Shakespere’. However ludicrous this choice appears in the context of the theatrical satire, it speaks to a new phenomenon in the discourse of the period. In Gull’s turn from the Old and the New Poet to Shakespeare, we can witness the comedic passing of a literary torch that will prove serious in subsequent centuries.

After publication of the 1596 Faerie Queene, I propose, it would be difficult for any poet concerned with authorial genealogy and literary history to confront Chaucer directly, without going first through Spenser. I further propose that Shakespeare understood this Spenserian genealogy, and made it the center of his intertextual method when re-working Chaucerian poems.8

The second most famous articulation linking Shakespeare with Spenser and Chaucer comes from William Basse in 1622:

Renowned Spencer lye a thought more nye

To learned Chaucer, and rare Beaumont lye

A little nearer Spenser to make roome

For Shakespeare in your threefold, fowerfold Tombe.9

In this strategy of literary commendation, Basse tries to create ‘roome’ for Shakespeare in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abby, next to the monuments of Chaucer, Spenser, and ‘rare Beaumont’.

A year later, in the most famous linking of Shakespeare with Spenser and Chaucer, Jonson alludes to Basse in his memorial poem to the First Folio, yet chooses to back a different strategy of memorialization:

My Shakespeare, rise; I will not lodge thee by

Chaucer, or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lye

A little further, to make thee a roome:

Thou art a Moniment, without a tombe,

And art alive still, while thy Booke doth live.10

Jonson does not need to lodge ‘Shakespeare’ by either the Old Poet or the New in Poets’ Corner because the ‘Booke’ of the First Folio is a sufficient ‘Moniment’ to keep Shakespeare’s ‘art alive still’. Like Basse, nonetheless, Jonson joins in the cultural process of trying to immortalize Shakespeare in terms of Spenser and Chaucer.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the genealogy linking the three authors forms the foundation for the English literary canon, as exhibited in 1664 by Knightly Chetwood:

Such was the case when Chaucer’s early toyl

Founded the Muses Empire in our Soyl.

Spencer improv’d it with his painful hand

But lost a Noble Muse in Fairy-land.

Shakespeare stay’d all that Nature cou’d impart.11

Like Jonson, Basse, and the Parnassus plays, Chetwood anticipates (we shall see) Shakespeare’s own strategy of bringing his authorship into alignment with the Old and New Poet. In an uncanny way, then, Gull gets the authorial genealogy right. Chaucer, Spenser, and Shakespeare, with their great successor Milton (rather than rare Beaumont), function as the cornerstones of the English canon for the ensuing centuries.12

In working specifically from a typological principle linking Spenser with Chaucer, Shakespeare could have taken the cue of Spenser himself. In The Shepheardes Calender, the New Poet calls Chaucer ‘Tityrus’, the name that Virgil had selected for his pastoral persona in the Eclogues. Complexly, Spenser writes Virgil’s pastoral achievement into Chaucer, so that by ‘Tityrus’ he means something like Chaucer in comparison with Virgil.13 Nowhere is the pre-Miltonic version of this history on more concentrated display than in a work that John Middleton Murray once called ‘the most perfect short poem in any language’ and I. A. Richards ‘the most mysterious poem in English’: ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’.14

As a key intertext for ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, critics have long proposed Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules, yet today most do not find the intertextuality significant enough to warrant a role in the critical conversation.15 The dearth of commentary on the two poems is unfortunate, because the similarities afford a new vantage point for viewing two literary giants who link the Middle Ages and the early modern period: what we might call the intertextual politics of authorship and literary form. Indeed, both poems use the author’s first-person voice, rely on the medieval convention of the bird poem, and do so allegorically. Both feature an assembly of birds and include a familiar literary convention, the bird catalogue. And both poems focus on the topic of love, use an avian gender dynamic to probe the heterosexual relation between male and female, and thus foreground the importance of chastity and mutuality between the sexes. Moreover, for both poems, critics suspect a deep allegory that addresses the politics of royal marriage, however obliquely each might negotiate it.

Recognizing the similarities between the two poems, we also need to register notable differences. Most obviously perhaps, ‘Phoenix’ differs from Parlement in the circumstance prompting the avian assembly. In Chaucer’s poem, the birds convene on Saint Valentine’s Day at Dame Nature’s bower to participate in the annual ritual of mate-choosing, while in Shakespeare’s poem the birds assemble to mourn the deaths of two birds, the phoenix and turtle, who have married but left no posterity. The formal features of the two poems also differ. Chaucer pens a 699-line narrative dream vision in Middle English, regularized through rhyme royal stanzas in an iambic pentameter line. In contrast, Shakespeare pens a 67-line philosophical lyric in modern English with two stanzaic structures, each in a different meter: thirteen four-line stanzas rhyming abba in the unusual meter of ‘a seven-syllable line with four evenly-spaced accents’16 or what Barbara Everett terms ‘broken trochaics’, followed by five tercets in a similar meter.17 The details of Chaucer’s long poem are so extensive, and of Shakespeare’s short poem so concentrated, that it is easy to understand why critics have dismissed the relation between the two as unrewarding. Yet recent work on authorship and intertextuality makes a return to this literary relation at the center of English literary history both timely and productive.18

Chaucer’s poem opens with a fiction about the author reading a book, Cicero’s Dream of Scipio. After falling asleep, the poet dreams that Scipio Africanus takes him for a walking tour through the Garden of Love and into the Temple of Venus, where they witness a parliament of birds assembling for the ritual of Saint Valentine’s Day. Three tersel eagles debate who will win the formel eagle sitting on Dame Nature’s wrist. In the end, however, Nature wisely lets the formel choose her own mate: ‘she hireself shal han hir eleccioun, | Of whom hire lest; whoso be wroth or blythe, | Hym that she cheest, he shal hire han as swithe’ (621–3). Yet in her response the formel asks for a year in which to make her decision: ‘I axe respit for to avise me, |And after that to have my choys al fre’ (648–9). Free from the pressures of masculine competition, she locates the authority for her choice solely within herself: ‘I wol nat serve Venus ne Cupide’ (652). With this judgment, Dame Nature allows ‘To every foul … his make | By evene accord’ (667–8). Before the birds scatter, however, and in accord with Nature’s rite, a few ‘synge a roundel … | To don Nature honour and plesaunce’ (675–6). The joyous ‘shoutyng’ (693) that succeeds the roundel awakens the author from his dream, prompting him to take up ‘othere bokes … | To reede upon’ (695–6).

Chaucer critics have long tried to decipher this avian allegory, and today most believe that the poem has political import, but they remain divided over which historical marriage Chaucer addresses. Most readings argue that the poem refers to the marriage of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia on January 14, 1382, when Richard rivaled two continental suitors, Friedrich of Meissen and Charles VI of France. The formel has also been identified as Philippa of Lancaster and the tercels as Richard, William of Hainault, and John of Blois. Perhaps the formel is even Princess Marie of France.19

While recognizing an occasional origin to the Parlement of Foules, we might turn alternatively to a feature of the poem that we can map more certainly: the poem’s clear three-part structure.20 Recently, Theresa Krier has suggested that each part figures a ‘different literary region’: part 1, in which Chaucer reads the Ciceronian dream book, figures what Krier calls the ‘Latinate, philosophical realm’; part 2, in which the poet visits the Garden of Love and Temple of Venus to witness the Saint Valentine’s Day ritual, figures ‘late-medieval, vernacular, courtly love poetry’; and part 3, in which Chaucer dreams that the birds sing the roundel only to be awakened by the subsequent shouting, figures lyric song.21 Krier adds that in the fiction of Love’s Labor’s Lost Shakespeare appropriates Chaucer’s poem, its three-part structure, and its final event, presenting a female who defers the choice in marriage for a year, in order to represent a generic move from comedy to lyric: ‘Shakespeare contemplates his place as dramatist in poetic genre history: he opens a space which the catalogues demarcate as specifically literary.’22

Krier’s work on the ‘literary’ nature of the intertextual linkage between Love’s Labor’s Lost and The Parlement of Foules has significant repercussions for interpreting the intertextual linkage between Parlement and ‘Phoenix’ (a work that Krier does not mention). For, in this lyric, readers also confront an opaque avian allegory that many interpret as political in orientation. For a long line of distinguished commentators—from Emerson in the nineteenth century to Everett in the twenty-first—the mystery results because the allegory appears to bedevil the poem’s formal beauty. As with Chaucer’s poem, a long list of contenders for the historical identities of the avian principles has emerged. As with Chaucer, too, one couple has received the most sustained support: the phoenix and turtle represent Queen Elizabeth and the earl of Essex.23 While such a political tenor may operate, it does not fully account for the poem’s remarkable poetic quality. What Shakespeare’s lyric, like Chaucer’s narrative poem, seems to require is an interpretive strategy that can wed the political to the literary.

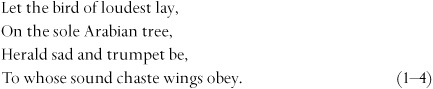

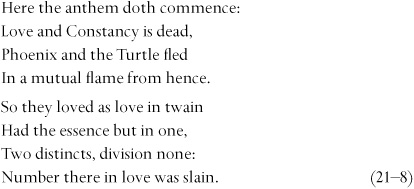

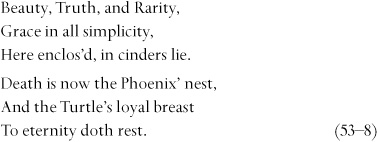

We can discover such a strategy by viewing ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, like The Parlement of Foules, as a poem about the politics of authorship. According to this view, Shakespeare’s lyric deploys an intertextual strategy that invents a new literary form. Significantly, ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ also has a clear three-part structure, marked by formal indicators in the text. This structure, I suggest, foregrounds the voice of the author in the creation of poetic form. In stanzas 1–5, the poet-narrator uses his lyric voice to call the birds to their funeral assembly. Then, in stanzas 6–13 this lyric voice records a second voice, the collaborative one of the avian choir singing a funeral anthem, as indicated by the transitional line between parts 1 and 2: ‘Here the anthem doth commence’ (21). Finally, in stanzas 14–18 a figure in the fiction of the anthem, named ‘Reason’ (41), steps forward to speak in yet a third voice, rehearsing a miniature Greek tragedy about the ill-fated deaths of the phoenix and turtle—this time marked in the text by the title ‘Threnos’ separating stanzas 13 and 14.

As in The Parlement of Foules, in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ the three-part structure represents a poetic voice in the process of inventing literary form. In Shakespeare, however, the poetic voice does not remain singular, as it does in Chaucer, nor does it simply progress from one ‘literary region’ to another. Rather, it modulates from one voice into another, in a telescoping fashion: from the singularity of the poet’s own first-person voice, to the collaborative voice of the funeral lament within the poet’s fiction, to the singular dramatic voice of a character within the choir’s (and poet’s) fiction. I can think of no other classical, medieval, or early modern poem that does precisely this.24 Momentously, Shakespeare imprints a lyric poem about the birds’ deaths not by clarifying the singular autonomy of the author’s voice but by displacing it. In the process, he constructs what may be the most self-reflexive representation of authorship in his canon.

The paradox of an authorial voice clarified yet displaced results, I argue, because Shakespeare lets collide the two major English models of authorship then available: Chaucerian self-effacement and Spenserian self-crowning. Both of these models are well known and can be explained quickly. In Book 3 of The House of Fame, the definitive Chaucerian moment occurs, when the poet refuses to record his name. ‘“Frend,”’ asks Aeolus of Chaucer himself, ‘“what is thy name? | Artow come hider to han fame?” | “Nay, for sothe, frend,”’ says the poet, ‘“I cam noght hyder, graunt mercy, | For no such cause, by my hed”’ (1871–5).25 Like Dante before him, Chaucer presents himself as a character in the fiction. Yet in The Canterbury Tales he presents himself as a minor character, showing up at the back of the pilgrimage, and eventually narrating a self-mocking romance, The Tale of Sir Thopas. In the narrative poems, Chaucer does foreground himself as the primary character, yet in The House of Fame he presents himself as humbly rejecting self-identification, producing a fiction in which his name is left blank and his identity held in question. Cunningly, Chaucer’s strategy for securing literary fame works through a fiction that rejects the quest for fame.26

In contrast, Spenser is our great poet of self-crowning. As Richard Helgerson argues, he is Renaissance England’s ‘first laureate poet’, and deploys strategies of self-presentation within his works to crown himself as national poet.27 Thus, in Book 4, canto 2, of The Faerie Queene, when interrupting the narrative to identify himself as Chaucer’s heir, Spenser pens perhaps his most conspicuous moment of laureate self-crowning.

Like Spenser, Shakespeare is well known to have engaged Chaucer throughout his career, from Love’s Labor’s Lost to Troilus and Cressida to Two Noble Kinsmen.28 Unlike Spenser, however, Shakespeare never claims to participate in the process Spenser calls ‘infusion sweete’. This process is Pythagorean in origin, and for Spenser it derives from the Ovidian principle of metempsychosis in Book 15 of the Metamorphoses.29 Yet in 1598 Francis Meres appropriates Spenser’s self-advertised Ovidian metempsychosis to describe Shakespeare’s authorial relation with Ovid himself: ‘As the soule of Euphorbus was thought to live in Pythagorus: so the sweete wittie soule of Ovid lives in mellifluous & honytongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his private friends, &c.’30 As Jonathan Bate remarks, Meres’ allusion to ‘the fifteenth book of the Metamorphoses’—where Euphorbus’ soul survives in Pythagorus—is precise, since ‘Pythagorean metempsychosis … becomes a figure for the translation of one poet into another.’31 Spiritual translation wittily metamorphoses into authorial translation, the migration of one author’s spirit into another. Thus, in the Legend of Friendship, when Spenser pauses to address Chaucer, he does not simply deploy Ovidian translation, but consolidates his authorial succession in English literary history. He completes Chaucer’s unfinished Squire’s Tale with a narrative that itself represents the authorial process of ‘infusion sweete’. In his completion of Chaucer’s tale, Spenser calls this process ‘traduction’ (4.3.13).32

The word ‘traduction’ has four primary meanings pertinent here. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it can mean:

1) ‘Conveyance from one place to another; bringing over, transportation, transference’;

2) ‘Translation into another language’;

3) ‘Transmission by generation to offspring or posterity; production, propagation; derivation from ancestry, descent’; and

4) ‘(rendering L. traductio.) A rhetorical figure consisting in the repetition of a word (or its derivatives) for some particular effect.’

In other words, traduction can refer to geographical travel, to linguistic translation, to genealogical transmission, or to verbal repetition. While the first meaning pertains to transportation, and the third to succession and inheritance, the second and fourth clearly pertain to the literary profession of the author. In the Legend of Friendship, Spenser’s epic allegory of military death and revival absorbs all four meanings, and channels them into his authorial relation with Chaucer.

Specifically, in his allegorical completion of the tale begun by the Old Poet, the New Poet tells how Agape learns from the Fates that her three sons, Priamond, Diamond, and Triamond, are destined to die prematurely, but she secures a form of immortality on their behalf. During the brothers’ battle with Cambel over his sister, Canace, Priamond dies first, but his soul migrates into the soul of Diamond; and when Diamond dies, his double soul migrates into that of Triamond, who thus possesses a triple soul: ‘through traduction was eftsoones derived, … | Into his other brethren, that survived, | In whom he liv’d a new, of former life deprived’ (4.3.13). The tripartite character of Triamond sustains complex philosophical and theological import, with roots in classical and Christian culture, principally Plato, Aquinas, Ficino, and Pico.33 Yet the equation between the process of traduction during a military battle and the earlier process of infusion during the literary competition allows us to discern Spenser’s vocational design. He completes Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale with an allegory that models the metaphysical principle ordering his authorial relation with Chaucer. In other words, he presents traduction as a tripartite process of both spiritual and literary immortality. Since he relies on traduction to complete the Old Poet’s tale, he associates the spiritual process with Chaucerian literary invention in order to succeed as national poet.

Shakespeare uses Spenser’s Chaucerian principle of traduction to structure not simply Love’s Labor’s Lost but also ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’. He does so to represent the process of authorship itself, and in particular to participate in the traduction of the two great English authors preceding him, both of whom were dead in 1601 when he composed ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ for Robert Chester’s Love’s Martyr. In this mysterious philosophical lyric, Shakespeare deploys Chaucer’s strategy of self-effacing displacement to present himself in Spenser’s laureate fashion: he is heir to the premier authors of English nationhood. In this way, ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ speaks to the transition from medieval to early modern that is the subject of the present volume.

Before looking into ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ for its Chaucerian and Spenserian genealogy, we might investigate what underlies their authorial technique of representing literary form as a three-part structure. To my knowledge, this topic has never been studied in its own right. Consequently, a brief overview of the key documents may be in order. Almost certainly, the topic traces to Plato, who said in the Republic:

there is one kind of poetry and taletelling which works wholly through imitation, … tragedy and comedy, and another which employs the recital of the poet himself, best exemplified, I presume, in the dithyramb, and there is again that which employs both, in epic poetry.34

Plato divides literature into three ‘kinds’ and concentrates on the means by which they work:

1) drama, which divides into tragedy and comedy;

2) dithyramb, which corresponds to early modern lyric poetry; and

3) epic poetry.

To distinguish among the three kinds, Plato relies on narrative technique or voice. Drama works through imitation of an action or mimesis; the dithyramb operates through the poet’s ‘recital’ of his own (first-person) voice; and epic combines the two.

Plato’s tripartite Greek model of authorial voice and literary form finds its most notable successor in the Roman Virgilian model of a literary career prefacing the earliest extant editions of the Aeneid:

I am he who once composed a song on a slender pipe; then, having left the woods, I made the fields nearby obey the settler even if he was very greedy, and the work pleased the farmers; now, however, (I sing of) the fearful (arms) of Mars (and the man).35

Effectively, here ‘Virgil’ speaks in his own epic voice, transposing Plato’s tripartite model of authorial voice and literary form to the three-part structure of his literary career.36 Virgil inaugurates his career with the youthful genre of pastoral in the Eclogues, foregrounding the idea of otium; he follows with the middle genre of didactic poetry in the Georgics, emphasizing the idea of labor; and he concludes with the mature genre of epic in the Aeneid itself, highlighting the idea of national duty. In other words, the Virgilian verses transport Plato’s schematic division of kinds into lyric, epic, and drama to a progressive typology connecting pastoral, georgic, and epic.

During the Middle Ages, Dante then transposes the Virgilian progressive typology to the formal practice of the Christian poet.37 In Book 2 of De vulgari eloquentia, Dante displays his gift for triadic pattern that is the hallmark of the Divine Comedy by mapping out the current state of poetry. In chapter 2, he aims to decide ‘which subjects in particular are worthy’ of ‘excellent poets’ who ‘use the illustrious vernacular’ (70). He concludes that the subjects should be ‘precisely those things which we esteem as most worthy of all’, and turns to the faculty psychology that estimates worth: the ‘tripartite soul … animal, vegetable, and rational’, by which ‘man … walks a threefold path’: the vegetable soul seeks the ‘useful’; the animal, the ‘pleasurable’; and the rational, the ‘right’. Since ‘we perform our every action because of these three things,’ vernacular poets should determine ‘which are the greatest things’ (71). The useful seeks ‘security’; the pleasurable, ‘love’; and the right, ‘virtue’: ‘these three things … appear to be the greatest things, to be treated in the highest way, that is, the things most closely adhere to them: prowess in arms, kindling of love, rectitude of will’ (71). Dante then connects this template linking inwardness, action, and literary subject to the literary history of his own time: ‘On these subjects alone, if I remember rightly, we find illustrious men who have composed poetry in the vernacular, both French and Italian: Bertran de Born on arms, Arnaut Daniel on love, Guiraunt de Bornelh on righteousness; also Cino de Pistoia on love, and his friend [Dante himself] on righteousness.’ After quoting these authors to represent each kind, he observes: ‘But I find no Italian up to now who has any poetry on deeds of arms’ (71). Dante’s phrase ‘any poetry on deeds of arms’ intimates how he aims to translate the three topics to three corresponding literary kinds.

In chapter 3, Dante then links the three subjects to literary form, inventorying a hierarchy of three kinds—the low sonnet, the middle ballate, and the high canzoni—and he suggests that the three ‘subjects worthy of the vernacular are to be treated [only] in the canzoni’ (72–3). Finally, in chapter 4 he relates form to style, introducing the lower elegiac, the middle comic, and the higher tragic, determining that the three subjects are to be treated only in the high, tragic style of the canzoni (74). He ends by turning to Virgil to distinguish between great and mediocre poets: ‘those whom the poet in Aeneid VI calls dear to god, and sons of the gods …, who were raised to heaven by their own ardent virtue’ and ‘those who, immune to art and knowledge and trusting only in their own wit, break into song about the highest things’: ‘let them cease in their presumption, and if they are geese by natural inclination or habitual apathy, let them not dare to imitate the star-seeking eagle’ (75). In this way, Dante presents a comprehensive practice—of literary styles, forms, life styles, and psychologies—as an Italian version of the Latin model he finds in Virgil.38

In the Februarie eclogue of The Shepheardes Calender, Spenser uses the three-part Dantean scheme to describe the career of ‘Tityrus’:

This passage has never been annotated in modern editions of Spenser. Of the criticism that exists, the most authoritative is by John A. Burrow in his Spenser Encyclopedia article on Chaucer: ‘Thus, in Chaucer’s tales or “novells,” the wisdom of the old proves acceptable to young Cuddie, and the youthful excitement of love and war once more stirs old Thenot. Chaucer’s poetry transcends the opposition between youth and age which the eclogue otherwise displays, because his combination of wisdom and story attracts both equally.’39 To the twin topics of ‘love and war’, we can add their corresponding genres, as well as a third kind, the ‘tale of truth’.40

In this passage, Spenser makes one of his most important contributions to a historical narrative about the reception of Chaucer. He understands Chaucer to have devised three kinds of novels:

1) ‘some of love’: love lyric;

2) ‘some of chevalrie’: chivalric epic; and

3) ‘a tale of truth’: didactic poetry.

Effectively, Spenser inventories a generically based Chaucerian triad. He divides Chaucer’s ‘tales’ into the three forms that Dante had outlined: ‘prowess in arms, kindling of love, rectitude of will’. Finally, the Chaucerian triad intersects with the Virgilian triad of pastoral, georgic, and epic.

We do not know why Spenser assigns the Dantean triad of authorial forms to Chaucer, but the recent work of Krier allows for fresh speculation: the Virgilian Spenser finds in The Parlement of Foules a three-part Dantean map of Chaucerian literary form, fused onto the tripartite structure of subjective literary voice.41 In ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, I suggest, Shakespeare reads the Spenser–Chaucerian genealogy accurately. He constructs a new genealogy that leads up to his own authorship, especially his most notable generic achievement: the reinvention of Western tragedy. By looking further at the formal three-part structure of Shakespeare’s 67-line philosophical lyric, we may see how its curious modulation of voices incorporates Spenserian and Chaucerian authorship.

In the first part of the poem (stanzas 1–5), the voice of Shakespearean lyric calls the Spenserian nationalist voice to assembly:

We do not know the identity of the ‘bird of loudest lay’, but long ago Alexander Grosart suggested the nightingale.42 Grosart may well be right, in part because Spenser had adopted the nightingale as an avian sign for his role as national poet.43 As the shepherd Thenot says in the November eclogue of Colin Clout, Spenser’s persona, ‘The Nightingale is sovereigne of song’ (25). Moreover, the ‘trumpet’ played by the bird of loudest lay is the traditional instrument of epic poetry (Faerie Queene 1. Pr.1), while the ‘chaste wings’ obeying the ‘sound’ of the trumpet evokes the amorous dynamic intrinsic to the genre of Spenser’s ‘epic romance’.44 Not surprisingly, the first line of the poem uses an ‘antique sounding dialect’, while the ‘Invocation [proceeds] in a Virgilian fashion’.45 Hence, the opening stanza may glance at Spenser’s status as the ‘Virgil of England’,46 and more precisely at the ‘antique’ topic and style that Shakespeare had assigned to Spenser as the ‘antique pen’ in Sonnet 106 (line 7).47

In the remaining stanzas of part one, Shakespeare selects the other avian participants for the funeral service. He banishes the ‘shriking harbinger’ and the ‘tyrant wing’, and selects the eagle to serve as judge, the swan as priest, and the crow as chief mourner. The details associate the troop with artistic sound, firm law, purified religion, and chaste duty, and suggest that the choir relies on its faith in song to combat mutability—a hallmark of Spenser, who ends up crowning his literary career with the Mutabilitie Cantos.48 In the avian choir, it is as if Shakespeare were fictionalizing a community of poets organized around the leadership of Edmund Spenser, perhaps in response to the New Poet’s own triumphal representation of this community in Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595).49

In part two (stanzas 6–13), Shakespeare records the anthem that the parliament of fowls sings:

Since Shakespeare’s paradoxes have been examined extensively, we may recall here simply that he represents ‘a wonder’ (32) in which two ‘distinct’ figures have the ‘essence but in one’—a wonder also well known to be central to Spenser’s poetics.50 Less often noted is the way that the avian anthem figures Chaucerian literary form, in particular the complaint.51 In the move from the first to the second part of the poem, then, Shakespeare’s lyric voice portrays the Spenserian voice ventriloquizing the voice of Chaucer, in the very move that Spenser had advertised in Book 4 of The Faerie Queene.

Yet Shakespeare does not simply reproduce the Spenserian ventriloquism of Chaucer in verse form. In this part of the poem, he overgoes the Chaucerian Spenser by inserting a third fictional voice, spoken by the figure of Reason, who, at least in retrospect, looks like a playful icon for Shakespearean tragic character itself, wittily adept at rehearsing the mystery of erotic union:

Reason, in itself confounded,

Saw division grow together,

To themselves yet either neither,

Reason undergoes an epiphany here, witnessing a miracle in which ‘division grow[s] together.’ Reason is so affected by this miracle that he proclaims his loss of reason, in the process introducing a new rational form of mind, humorously animated by eros. Shakespeare may glance at the Parlement, for one of the tercels remarks, ‘Ful hard were it to preve by resoun | Who loveth best this gentil formel here’ (534–5). Dame Nature ignores him, and also humorously contradicts her earlier judgment to let the formel make her own choice: ‘But as for counseyl for to chese a make, | If I were Resoun, thanne wolde I | Conseyle yow the royal tercel take’ (631–3).

As Shakespeare’s rhyme of ‘threne’ with ‘scene’ concluding part two above anticipates, in the third part of the poem the poet-playwright introduces a third literary form: that of tragic theater. In the unit titled ‘Threnos’, he depicts the mysterious contents of Reason’s dramatic tragedy:

In this Spenserian allegory, the author’s phrase ‘To eternity doth rest’ is especially resonant, meaning either that the breast of the turtle will rest until eternity or that the turtle’s breast will rest eternally in death. The ambiguity stakes out the very ground for and transition between two models of death that recent commentators locate in the tragic theater of Shakespeare: the traditional Christian model of death as salvation, and the one to which it gives way during the seventeenth century, death as annihilation.52

As commentators observe, the next two stanzas—in which the phoenix and turtle fail to leave behind a ‘posterity’ because of ‘married chastity’ (59–61)—leave Reason staring into the void: ‘Truth and Beauty buried be’ (64). This miniallegory is as fine a rendering as we have of the erasure of Spenser’s theological signature in the Legend of Holiness, where repeatedly we discover versions of the Satyrs’ innate attraction to Una: ‘They in compassion of her tender youth, | And wonder of her beautie soverayne, | Are wonne with pitty and unwonted truth’ (1.6.12.5–7; emphasis added).

Shakespeare’s final stanza then takes his poem more fully into tragic territory:

According to Everett, ‘the turtle’s breast rests to eternity with an absoluteness that makes dying the most active experience of a life-time, a wordless reversal of that calming with which the poem begins.’53 What Shakespeare immortalizes is not the Christian soul ascending to Spenser’s New Jerusalem (Faerie Queene 1.10.55–9) but the body’s eternizing performance of death as annihilation. This versified performance may be the poem’s greatest achievement.54

To summarize, ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ ends up depicting an historic typology of authorship, in which the literary voices of Spenser, Chaucer, and Shakespeare modulate through the poem’s three units:

1) In part one, the Shakespearean lyric voice represents the Spenserian voice of epic romance calling the fiction of the avian choir to life.

2) In part two, the Shakespearean lyric voice depicts the Spenserian voice appropriating the voice of Chaucer, as the avian choir within the fiction values the philosophical mystery of the birds’ Neoplatonic conjunction and mourns the passing of their ‘mutual flame’.

3) In part three, the Shakespearean lyric voice dramatizes the loving voice of Reason, a character within the fiction of the anthem who presents the ‘Threnos’ as a Greek tragedy because the phoenix and turtle have chosen ‘married chastity’ over offspring.

In this way, the three-part structure contains a representation of Shakespeare’s intertextual method itself. Through ‘traduction’ and ‘infusion sweete’, the voice of Spenser ventriloquizes the subjective spirit and literary form of Chaucer, and then, successively, the voice of Chaucer ventriloquizes the dramatic voice of Shakespeare. In the end, it is this third author who survives, like Spenser’s triple-soul figure of artistic traduction, Triamond.

Although ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ may gesture to a national political crisis, it formally clarifies only the authorial voice addressing that crisis, not the crisis itself. The voice the poem identifies is not just that of the Shakespearean lyric poet writing the poem but a tripartite intertextual voice composed of nationally significant authors. In this lyric, Spenserian romance epic modulates into Chaucerian complaint, and together they modulate into Shakespearean tragedy.55 This complex intertextual model of sixteenth-century authorship, more than the twentieth-century’s simplistic ‘man of the theatre’, best historicizes Shakespeare’s professional production.56 In 1601, Shakespeare may be a consummate theatrical man, but he is also an author with a literary career. He succeeds in combining a philosophical lyric poem like ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ alongside a watershed tragedy like Hamlet. In the process, Shakespeare crafts out a professional space for his succession from Spenser and Chaucer, exquisitely poised for the very title he will soon come to inherit: England’s National Poet.57

For generous and expert help with the present essay, I am grateful to Robert R. Edwards, Steele Nowlin, and John Watkins.