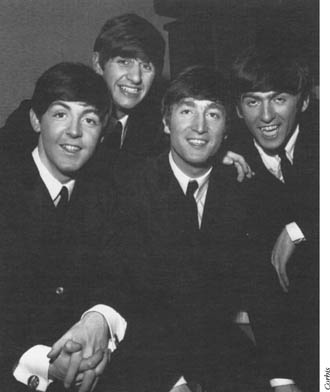

The “Fab Four” sporting “mop-tops” and velvet-collared suits. From left: Paul, Ringo, John, and George.

Corbis

The Beatles were the most musically innovative and internationally popular rock band of the 1960s. Beginning with an amalgam of American rhythm and blues and popular music, they developed an immediately recognisable style, with songs that had both melodic appeal and articulate lyrics. Their most important legacy was to show that talented young musicians could break with convention and create distinctive music within a simple idiom. This opened the floodgates for the outpouring of musical creativity in popular music of the mid- and late 1960s.

The Beatles were rhythm guitarist John Lennon (b. October 9, 1940, d. December 8, 1980), bassist Paul McCartney (b. June 18, 1942), lead guitarist George Harrison (b. February 25, 1943), and drummer Ringo Starr (b. Richard Starkey, July 7, 1940). Lennon and McCartney were the chief songwriters and singers; the others composed and sang more occasionally. In their recordings, Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison sometimes stepped outside their principal instrumental roles, with McCartney playing drums, keyboards, and guitars, Lennon playing harmonica and keyboards, and Harrison playing the Indian sitar.

The Beatles were influential not only in setting the tone for the music of the period, but also in matters of fashion, hairstyles, and even political views. For example, their interest in Indian philosophy from 1966 onward was taken up by millions in the West.

The Beatles’ voracious quest for new sounds led to innovations in studio technology, as engineers for their record label, EMI, built devices to create the effects the Beatles were seeking. Their producer George Martin encouraged them to use harpsichords and orchestral instruments in ways that were intrinsic to the songs, and not merely the added sweetening.

All four Beatles were born and raised in Liverpool and its suburbs. The kernel of the band was Lennon’s mid-1950s band, the Quarry Men, which played skiffle: lively versions of folk and blues standards performed on guitars and various homemade instruments. McCartney was introduced to Lennon at a Quarry Men show in summer 1957, and joined soon after. He later brought Harrison into the band.

By the end of 1957, Lennon and McCartney were writing songs. Though they decided early on that all their compositions would go out with a joint credit, they usually wrote separately. Because each tended to sing his own songs, and because of obvious stylistic differences—Lennon’s preference for clever, involved lyrics, and McCartney’s talent for melodic sweep—it was easy to determine a song’s author.

By 1958, only the nucleus of Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison was left of the Quarry Men. Late in 1959, Lennon’s friend Stewart Sutcliffe, a talented painter, joined as bass guitarist. At Sutcliffe’s suggestion, the group renamed themselves the Beatles in 1960. At the end of that year, Sutcliffe left the group to continue his art studies. He died in 1961.

After a succession of drummers, Pete Best joined the group in late 1960, just before the band played the first of several engagements in Hamburg. There, the group forged its sound by playing all-night sets in various clubs in the St. Pauli district. After Sutcliffe’s departure, McCartney switched from guitar to bass. It was a decisive step: McCartney approached the instrument as a would-be lead guitarist. He tended to play flowing, melodic bass lines, rather than merely holding the chord roots or playing standard patterns.

By 1961, the Beatles had built up a loyal following at the Cavern Club in Liverpool, and were making recordings in Hamburg as a backing band. Towards the end of the year, they engaged a manager, Brian Epstein, who secured them a recording contract with Parlophone, an EMI subsidiary. Three months later, drummer Pete Best was replaced by the extrovert Starr. The “Fab Four” had been born.

Epstein set about transforming the new lineup from a leather-clad dance band into a professional ensemble, with an instantly recognisable image that included collarless matching suits and a brushed-forward hair style. But the Beatles were by no means a matter of style over substance. Their first single, “Love Me Do"—simple and bluesy, but with a mildly exotic edge—was a modest hit at the end of the 1962. Next, the more upbeat “Please Please Me,” became the first in a long series of British No. 1 records that, in 1963 alone, included “From me to you,” “She Loves You,” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” The Beatles also recorded albums in 1963—Please Please Me and With the Beatles, both essentially studio versions of the group’s stage sets, combining originals and cover versions of mostly American R&B hits.

The Beatles toured almost continuously in 1963, playing as many as three shows a day, and appearing regularly on radio and television. Such was their success that the press coined the term “Beatlemania” to describe the wild audience response at their performances. At the same time, serious critics began pointing out the originality of the growing Lennon-McCartney song catalogue.

The Beatles’ success spread to the U.S. in the last weeks of 1963, and in February 1964 they undertook a short, but highly successful, tour that included three appearances on TV’s Ed Sullivan Show and concerts at the Washington Coliseum and the Carnegie Hall. A summer tour took the Beatles to Europe, Asia, Australia, and back to the U.S., confirming them as a worldwide phenomenon. In the meantime, United Artists signed them to a film contract, and work on their screen debut began early in 1964.

Their first film, A Hard Day’s Night, offered a lightly fictionalised glimpse into the group’s daily routine— dodging fans, rehearsing, and performing, but also coping with the fact that they had become prisoners of their own fame. It also caricatured the group’s distinctive personalities: Lennon as the sharp, witty Beatle; McCartney as the cute and personable one; Harrison as shy, cutting, and focused on his own music; and Starr, the droll comedian.

The group’s third album, also called A Hard Day’s Night (half of its songs are in the film), consisted almost entirely of Lennon-McCartney compositions, and was the pinnacle of the Beatles’ early period. Its songs were fresh, vibrant, and in some cases (McCartney’s “And I Love Her,” and Lennon’s “If I Fell”) irresistibly melodic. At the end of 1964, A Hard Day’s Night was followed by Beatles for Sale, a much darker collection of songs that showed the strains of constant touring. After the creative explosion of A Hard Day’s Night, the group returned to its earlier mixture of originals and covers, and moved slightly in the direction of country and western. Yet the very best of the material—Lennon’s “I’m a Loser,” and “No Reply,” for example—showed an introspection that had not previously been part of the Beatles’ arsenal, while such songs as “Eight Days a Week” showed that they could still make bright, catchy pop records.

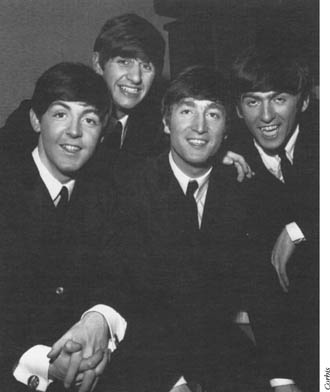

The “Fab Four” sporting “mop-tops” and velvet-collared suits. From left: Paul, Ringo, John, and George.

Corbis

The Beatles’ 1965 film, Help!, was a comic adventure fantasy, with little creative input from the Beatles. The associated album, however, broke new ground. For several of the Help! recordings, they brought in outside musicians for the first time: Lennon’s folkish “You’ve got to Hide Your Love Away” was embellished with recorders, and McCartney’s bittersweet ballad “Yesterday” was given a string-quartet arrangement. The group’s own texture was now more open: acoustic guitars, keyboards, and percussion instruments were plentiful, although live the Beatles largely continued to use their electric guitar, bass, and drums setup.

In Rubber Soul recorded late in 1965, the Beatles continued to explore the folk-rock amalgam heard on Beatles for Sale and Help!, but Lennon’s, McCartney’s, and now Harrison’s, songwriting had reached a new level. In a sense, Rubber Soul is a song cycle: its songs examine the well-worn theme of love from every angle, ranging from conventional declarations (McCartney’s “Michelle”), to raging jealousy (Lennon’s “Run for Your Life”), to unromantic nonchalance (Harrison’s “If I Needed Someone”), to love as a social force (Lennon’s “The Word”).

In the 1966 sessions that produced Revolver, the Beatles shed their stage instrumentation and used everything from Indian ensembles to brass bands, from electronic distortion to backwards instrumental and vocal sounds. So complex was this music that they did not attempt to reproduce it on stage, and on their aimless 1966 tour they played only older material.

That summer, the Beatles announced that henceforth their efforts would be confined to the recording studio. By the end of the year, they had started recording Lennon’s spectacularly image-laden “Strawberry Fields Forever,” and McCartney’s bright “Penny Lane,” and were at work on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The tendencies first heard on Revolver came to fruition on this colourful album, which expands the instrumental arsenal further to include a full orchestra.

The freedom that yielded Revolver and Pepper led to the group’s unravelling. After Epstein’s death in August 1967, the Beatles resolved to manage their own affairs. Their avant-garde TV film, Magical Mystery Tour, was a critical flop, but its soundtrack, which included Lennon’s “I Am a Walrus,” was widely praised. The Beatles also recorded a handful of new songs for an animated feature film based on the Lennon-McCartney song “Yellow Submarine.”

In early 1968, the group followed Harrison to Rishikesh, India, for a course in transcendental meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The experience yielded close to 40 new songs, including Starr’s songwriting debut, the country-tinged “Don’t Pass Me By.” The result was a two-disc compendium of popular styles—from crooning to hard rock and blues, from folk to calypso, doo-wop, and surf music. Officially called The Beatles, the set is better known as the “White Album,” because of its blank cover.

Tensions erupted within the band during these sessions, and they were magnified when the Beatles reconvened in January 1969 to record new material, with a camera crew on hand to record the event. The music was far simpler than that of Revolver or Pepper, indeed, the Beatles’ aim was to get back to their rock‘n’roll roots. These huffy sessions eventually yielded the album and film Let Lt Be, but the project was shelved after the recording of Abbey Road, the album the Beatles consciously made as their swansong. Though by no means a return to the freewheeling experimentation of 1967, Abbey Road nevertheless showed Lennon dabbling with MINIMALISM in “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” and McCartney creating a quasi-symphonic suite out of song fragments to close the album.

Abbey Road was the last time the Beatles worked together. They went on to pursue solo careers, with varying success. Lennon, on the eve of a comeback after a self-imposed five-year hiatus, was assassinated by a crazed fan in New York in 1980. McCartney went on to make over 20 albums, and undertook several world tours. Harrison was more reclusive, but in 1988 formed the critically acclaimed Traveling Wilburys with Bob DYLAN, Tom Petty, and Roy Orbison. After a few early hits, Starr’s recording career effectively came to an end. The three surviving Beatles reunited in the mid-1990s to complete two of Lennon’s unfinished recordings, “Free As a Bird” and “Real Love.”

The Beatles set the standard for creativity and experimentation in pop songwriting, arranging, and recording, and they pioneered the use of the pop album as a unified sequence of songs. Their work paved the way for a whole generation of musicians, from THE WHO, the KINKS, and David BOWIE, who expanded on the Beatles’ efforts in thematic unity, to Jimi HENDRIX and PINK FLOYD, who expanded on their sonic innovations.

Allan Kozinn

SEE ALSO:

BRITPOP; FOLK ROCK; PROGRESSIVE ROCK; ROCK’N’ROLL.

FURTHER READING

MacDonald, Ian. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties (New York: Henry Holt, 1994);

Woog, Adam. The Beatles (San Diego, CA: Lucent Books, 1998).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Abbey Road; A Hard Day’s Night; Help!; Please Please Me; Revolver; Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.