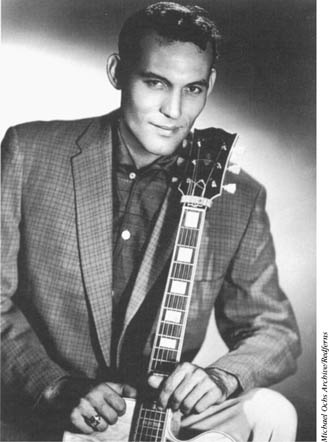

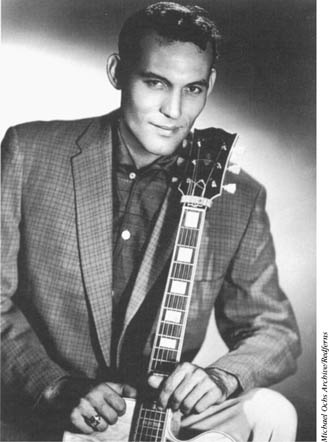

The driving guitar style of Carl Perkins produced some of the most exciting rockabilly music. His recording of his own song “Blue Suede Shoes” was a smash hit in 1956.

The musical style of rock’n’roll is generally considered to have derived from rhythm and blues (R&B), and became popular principally with teenagers in the 1950s. It developed in various regions of the United States, roughly from 1954 to 1964, as an extension of the R&B that had become popular in the 1940s, during and especially after World War II.

R&B developed in Southwestern and Midwestern American urban centres such as Kansas City, Chicago, and St. Louis, and was influenced by jazz, the blues, and black gospel music. R&B bands were similar to small jazz combos: they had a lead singer backed by bass, drums, piano, and electric guitar as the rhythm section, and a horn section consisting of one to three saxophones and perhaps a trumpet. From the blues, R&B borrowed its textual structure, chord progression, performance style, and song subject matter; it also borrowed the enthusiastic, exciting performance style of black gospel music.

The rhythm section played a continuous rhythmic ostinato derived from boogie-woogie that placed a strong accent on the second and fourth beats of the quadruple measure. This accented beat (the “rhythm” in “rhythm and blues”) became known as the backbeat, and was to figure prominently in the development of rock’n’roll. The popularity of R&B gradually spread throughout the country during the postwar years, in some markets completely supplanting jazz or blues styles.

In the early 1950s, disc jockey Alan FREED noticed that African-American R&B was attracting a new audience: middle-class, suburban, white teenagers. Freed began broadcasting a late-night R&B radio program, sponsored by a local record store, from Cleveland station WJW in June 1951, calling his program Moondog’s Rock’n’Roll Party. The term “rock’n’ roll’—a phrase frequently used in the lyrics and titles of the R&B songs Freed played on his program—was originally a euphemism both for dancing and for sex. However, in Freed’s thinking “rock’n’roll” was the R&B he played for his white teenage audience.

“Rhythm and blues” for Freed became a heavily backbeat-accented music performed by black musicians for a black audience, while “rock’n’roll” was the same music by the same performers, but for a white audience. Freed’s radio program became so popular that he was eventually hired by New York City station WINS to broadcast nationally.

Around 1953, it became an accepted practice for white performers to copy R&B songs, often changing the more risqué lyrics to more acceptable versions, and to release these new “cover” versions to compete with the original R&B recordings. With more radio stations playing music by and for white Americans than by African-Americans, the cover versions became better known than the originals, with the result that more performance royalties were paid to the cover artists than to the original performers. Some of the best-known examples of this include Pat Boone’s recordings of LITTLE RICHARD’S “Tutti Frutti” and Fats DOMINO’S “Ain’t That a Shame,” Elvis PRESLEY’S version of Willie Mae Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” and Bill HALEY’S cover of Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” By 1954, “rock’n’roll” had come to denote R&B songs covered by white performers, as well as original material by these performers written to imitate the R&B style.

The driving guitar style of Carl Perkins produced some of the most exciting rockabilly music. His recording of his own song “Blue Suede Shoes” was a smash hit in 1956.

However, there is more to the musical style of rock’n’roll than white performers copying black R&B. Both black and white artists contributed to the development of rock’n’roll in the 1950s by combining elements of the blues and other musical styles in which they had been raised. Rock’n’roll developed slightly differently in different areas of the U.S.—in the Northeastern U.S. and in New Orleans, in Memphis, and in Chicago—through the fusion of African-American blues, R&B, and the popular music styles in those areas. The music that came out of these areas exerted a strong influence on music produced in other parts of the country throughout the 1950s.

The rock’n’roll that came out of the Northeast was represented by Bill Haley and His Comets, and by vocal groups usually referred to as “doo-wop.” Bill Haley was originally a country singer known for his yodelling skill, and was popular in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Ohio. In 1949, backed by his group the Four Aces of Western Swing, Haley began to perform R&B songs at his live shows. After reorganising his band into the Western swing group the Saddlemen, Haley made his first record, a cover of Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88.” Eventually the Saddlemen became the Comets, and in 1954 the group recorded their classic “Rock Around the Clock.”

Originally issued as a B-side, when “Rock Around the Clock” was used for the opening credits of the film The Blackboard Jungle in 1955, the film’s popularity with teenagers raised the song to the top of Billboard magazine’s sales charts, making it the first No. 1 rock’n’roll song in both the U.S. and the U.K. The song has since become synonymous with 1950s nostalgia, having appeared on the soundtrack of the film American Graffiti (1973), and as the title song for the first season of the hugely successful television show Happy Days (1974).

The Comets’ music is a combination of elements from R&B and country music, with jazz guitar performance techniques added. Their style is characterised by a steady, mechanical approach to meter, fast tempos, even melodic rhythms, slapped bass technique, and steel guitar. One can also hear vocal techniques borrowed from country music, combined with the emphasised backbeat, boogie-woogie accompaniment, and the harsh tenor saxophone sound of R&B. The lead guitarists were influenced by the playing style of jazz guitarist Charlie CHRISTIAN. Bill Haley and His Comets were immensely popular from roughly 1954 to 1957.

The other type of rock’n’roll from the Northeast—vocal group rock’n’roll—is a diverse category of music. The vocal groups were primarily made up of African-American singers from the large urban centres like Philadelphia, New York, Detroit, and Los Angeles. The type of song ranges from fast-tempo novelty songs by the Coasters to slow-tempo love ballads by the Platters. While vocal groups were as individual as their members, there are some general style characteristics that set it apart from other rock’n’roll styles. The main focus is on the vocals—usually a high tenor lead vocal supported by three to four singers in close harmony. The entire group is supported by an R&B band kept deep in the background so as not to intrude over the vocals. The supporting vocals often vocalise syllables (ahs, oohs) or sing syllables like “d-doo wah” (giving the style its name “doo-wop”).

While the other rock’n’roll styles depend heavily on the 12-bar blues progression, many doo-wop songs are built on the progression using tonic-submediant -subdominant-dominant (I–VI–IV–V). These doo-wop vocal groups, which were heavily influenced by popular male singing groups such as the INK SPOTS and the Mills Brothers of the 1930s and 1940s, include the Orioles, Penguins, Platters, Coasters, Drifters, Dion and the Belmonts, and the FOUR SEASONS.

The New Orleans style of rock’n’roll is based on the rhythm and blues associated with that city, in combination with musical elements from boogie-woogie piano. The principal rock’n’roll artists to rise to popularity in New Orleans from around 1953 to 1963 included Clarence “Frogman” Henry, Professor Longhair, Lloyd Price, Smiley Lewis, Antoine “Fats” Domino, and “Little” Richard Penniman.

The J&M recording studio owned by Cosimo Matassa was instrumental in developing the New Orleans sound. The sound is characterised by a deep bass foundation, concentration on the lower range of instruments, loose rhythms based on boogie-woogie rhythms, melodic surface rhythms that varied from a lively, bounced beat to a slow, intense shuffle, and an emphasis on vocal expression making songs either exuberantly joyful or incredibly depressed. The saxophone- and piano-oriented New Orleans style of rock’n’roll gradually declined in popularity during the early 1960s in favour of the electric guitar bands of rock.

The rock’n’roll style that developed in Memphis came into prominence in 1954; it combined musical elements of rhythm and blues with those of country. The style was referred to as “country rock” by the musicians who played it, though it is now most often referred to as “rockabilly,” a combination of rock’n’roll and hillbilly (country) music.

Bands were essentially country string bands with electric and acoustic guitars, and acoustic bass; after 1955 piano and drums were often included. The sound is dominated by a tinny, treble foundation in the guitars and nasal vocals influenced by country music. Vocals are characterised by yelps, stuttering, and yodels from country music, and growls, wails, and slurred words from the blues.

The Memphis country rock style was largely the product of Sam Philips’s Sun Recording Studio, where leading artists such as Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Roy Orbison recorded. Jerry Lee Lewis, the self-styled “king of rock’n’roll,” also recorded with Sun.

Elvis Presley came to the notice of Sam Philips when as a teenager he paid to record a track at the studio for his mother’s birthday. He cut some singles for Sun, appeared on the Grand Ole Opry, and toured clubs. He was 21 when he recorded “Heartbreak Hotel” for the RCA label in January 1956—an event now considered to be the beginning of rock. It shot to the No. 1 spot in the U.S. charts where it remained for two months. Other hits swiftly followed—“Hound Dog,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” and “Love Me Tender.” His appearances on stage caused hysteria among teenage fans, encouraged by his suggestive hip gyrations. But at the end of the decade he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and by the time he was discharged his importance on the rock’n’roll scene had begun to fade.

Carl Perkins’s abrasive, driving guitar style was the epitome of rockabilly and influenced many later groups, in particular the BEATLES. Soon after his own recording of “Blue Suede Shoes” was a huge hit, he was seriously injured in a car accident and his career lost momentum. Nevertheless, many of his later singles are regarded as rockabilly standards.

Other performers associated with the rockabilly style, though not through Sun Studios, include the EVERLY BROTHERS, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Dale Hawkins, and Rick Nelson.

Gene Vincent’s career was launched hot on the heels of Presley’s debut, as the record labels competed to find the next rock sex symbol. Vincent’s first (and biggest) hit was the exciting “Be-Bop-A-Lula,” which almost convinced Presley’s mother that it was cut by her son. The record was a huge hit in both the U.S. and Britain. But Vincent’s sultry, menacing image made him difficult to promote in the U.S., and he eventually found a manager in Britain to handle his declining career. Eddie Cochran was a great rockabilly guitarist who shot to fame in 1958 with his smash hit “Summertime Blues.” Although his career was short (he died in a road accident in 1960, at age 22), his influence on rock’n’roll was considerable.

Memphis country rock’n’roll remained a popular style into the 1960s and was extremely influential on the growth of rock in the 1960s and beyond. The 1980s saw a renewed interest in the rockabilly style with groups like the Stray Cats and the Cramps becoming popular.

Chicago rock’n’roll developed in the mid-1950s from the urban blues and R&B that had been popular there in the 1940s and 1950s. Chicago rock’n’roll is a guitar-based style, as opposed to the hard-edged saxophone sounds of Chicago R&B. The Chicago rock’n’roll guitar, derived from urban blues techniques, features frequent sliding on the strings, bent notes, and multiple-stopped strings. There are generally faster tempos and harder-driving backbeat emphases than in either urban blues or rhythm and blues. The rock style also features more even beat subdivisions, rather than the boogie-woogie swung beat heard in R&B, and performers generally stay closer to the beat than do blues performers.

The two main exponents of Chicago rock’n’roll are Chuck BERRY and Bo DIDDLEY. Berry’s guitar style is melodic, featuring repeated riffs, bent notes, and bent multiple stops, a straight eighth-note accompaniment that has become the trademark of the rock’n’roll sound, and a frequent use of syncopated rhythms. Many of Berry’s songs (“Roll Over Beethoven,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Carol”) begin with a guitar introduction that has become a cliche in rock music.

Berry was to become a role model for many young rock’n’roll bands, and was to have a seminal influence on the rock bands of the 1960s, including the BEACH BOYS, the Beatles, and the ROLLING STONES.

Bo Diddley grew up in Chicago, playing street music as a boy, and was launched in 1955 by the new Chess label, along with Chuck Berry. Diddley’s guitar style is harder and more rhythm-oriented than Berry’s, defined by a heavy-handed picking style, full-chorded rhythmic patterns, and solos based on rhythms rather than melodies. The classic Bo Diddley rhythm—which he refers to as the “Bo Diddley beat’—is derived from the African juba rhythm heard frequently in children’s games—the same rhythm as the shoeshine chant “shave and a haircut, two bits.”

The music of Buddy HOLLY is also a part of the 1950s rock’n’roll scene, being a fusion of elements from Chicago and Memphis rock’n’roll styles combined with his own personal style. “That’ll Be the Day,” released in 1957 when he was 21, was an instant hit, and was quickly followed by what are now regarded as rock’n’roll standards—"Peggy Sue,” “Oh Boy,” and “Maybe Baby.”

Holly’s group, the Crickets, featured a self-contained line-up of two electric guitars, bass, and drums that would set the pattern for rock groups of the 1960s and beyond. He also experimented with and pioneered innovative techniques in the recording studio that were to become widely used.

The different styles of rock’n’roll that developed simultaneously in the mid-1950s blended musical elements of the blues, country, R&B, jazz, and a variety of American folk music into a unique style that has dominated the pop music landscape for the second half of the 20th century.

Steve Valdez

SEE ALSO:

BLUES; BOOGIE-WOOGIE; DOO-WOP; GOSPEL; ROCK MUSIC.

Clifford, Mike, ed. The Harmony Encyclopedia of Rock (New York: Harmony Books, 1992);

Gillett, Charlie. The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll (London: Souvenir, 1996);

Logan, Nick, and Bob Woffinden. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock (New York: Harmony Books, 1977).

The Buddy Holly Collection; Chuck Berry on Stage; Legendary Masters: Eddie Cochran; Bo Diddley: I’m a Man; Bill Haley: Rock Around the Clock; Elvis Presley: The Sun Sessions.