Since the l6th century, to have “the blue devils,” or to be “blue” has referred to a fit of melancholy. Then, around 1900 the term was adopted by players of a style of African-American folk music that expressed just such a mental state. A typical early blues song is characterised by a repeated musical sequence of three chords played over 12 bars, with a three-line structure to the lyrics consisting of a repeated line and a rhyming refrain. The instruments that were most often used in early blues were the guitar and voice, sometimes accompanied by a harmonica or a piano. The impact of blues on the subsequent development of American music has been enormous. Everything from rhythm and blues (R&B) to rock’n’roll, from gospel to rap, would be unrecognisable without its influence. They all owe a debt to the mournful wail of the blues singer; the simple and infectious rhythmic beat; and the pulled or bent “blue note” of the blues guitarist. The legendary blues guitarist and singer B. B. KING called blues the “mother of American music.”

The roots of the blues are deep in the experience and music of African-Americans during slavery in the South. The slaves sang unaccompanied worksongs, in which the leader of a workcrew timed the work by singing, and the other slaves answered in unison. The worksongs consisted of a long, loud musical shout, rising and falling and breaking into a falsetto. The group leader would add improvised embellishments and intentionally hit certain dissonant notes—the ancestor of the “blue note”—in a style that harkened back to the music of the slaves’ African ancestors. Slaves also invented spiritual songs to express their faith in God and in the rewards of the afterlife, sung in a vocal style similar to that used in the worksongs. And they sang ballads, traditional songs that told stories and were passed down from one generation to the next.

After the Civil War and emancipation ended the plantation system, the tradition of the worksongs persisted in the improvised songs, or “hollers,” of individual workers. The traditional ballad, which flourished in the second half of the 19th century, unlike the freer worksongs, contributed a stricter, more conventional harmonic progression to blues songs. Many of the ballads, including “John Henry,” “Frankie and Albert” (also known as “Frankie and Johnny”), and “Stack O’Lee” (or “Stagger Lee”) were transformed into blues songs and re-recorded repeatedly. Like other folk music, the blues conveys the feelings and experiences of ordinary people. Blues songs cover topics such as natural disasters, crime, prison life, farm life, sickness, sexual relationships and social injustice. But despite the often gloomy subject matter, the blues has always been party music, to be shared with a crowd at social gatherings. Playing the blues was a way of exorcising sorrow.

The precise origins of the blues as we know it, however, are unclear: no one knows who the first person was to sing and play the blues. In his autobi- ography, composer W. C. Handy recalled first hearing a blues singer at a train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi, in 1903. The man played the guitar by pressing a knife blade against its strings, producing a whine like a human cry. Singer Gertrude “Ma” RAINEY claimed to have heard a young girl singing the blues in Missouri in 1902. Jelly Roll MORTON also reported hearing blues in New Orleans in 1902. Some scholars date the origin of the guitar-and-voice blues even further back, to the late 1890s.

By the early 1900s, a standard blues form seems to have evolved. The “songster” sang a succession of three-line stanzas—a repeated couplet and an improvised rhyming refrain. The words reflected the feelings of ordinary African-Americans:

I’m troubled in mind, baby, feelin’ blue and sad

I’m troubled in mind, baby, feelin’ blue and sad

The blues ain’t nothin’ but a good man feelin’ bad.

These laments were supported by a fixed cyclic 12-bar “blues progression,” which passed through tonic, subdominant, tonic, and dominant chords before returning once again to the tonic. This progression, of which there were many variants, could be played in any key, although E and A were the most widely used in blues. The early rural blues singers, many of whom were musically illiterate, improvised around this relatively simple structure, introducing the characteristic blues sounds of flattened “blue notes” and growling or rasping vocals.

The part of Mississippi known as the Mississippi Delta is generally credited as the birthplace of the blues. What gives the Delta its prominence in blues lore is the fact that many important blues musicians lived there or were born there, from the early pioneers, such as Charley PATTON, Son HOUSE, and Robert JOHNSON, to musicians of later generations who migrated north, including Big Bill BROONZY, Muddy Muddy WATERS, B. B. King, and John Lee HOOKER. Patton is especially deserving of the title “father of the blues,” as he was one of the first to combine the melodies and chord progressions common to the blues, and one of the first to record them.

From the end of the Civil War, in 1865, until well into the first half of the 20th century, the Mississippi Delta had been home to poor farmers, known as sharecroppers, who attempted to earn a living and feed their families by working plantation owners’ land in exchange for payment when the crops were harvested. The sharecropper’s life was one of hard work, low wages, and little leisure. Saturday was a day off, and itinerant musicians, some of whom farmed during the week, travelled through the small Delta towns, entertaining at juke joints (bars with music) and parties. In this way, blues music spread from town to town.

The blues also developed in pockets throughout the South outside the Mississippi Delta. Early blues musicians in the Piedmont area of the Southeast included Blind Willie McTell, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Blake, and Josh White. Lightnin’ Slim and LEADBELLY hailed from Louisiana. Early Texas bluesmen included Blind Lemon JEFFERSON, Texas Alexander, Lonnie JOHNSON, and T-Bone WALKER. (The number of blind musicians is probably explained by the fact that playing guitar was one way a blind person could earn a living.) Texas also developed a strong barrel-house piano tradition, while Memphis was home to popular “jug bands”—African-American ensembles in which jugs were used as bass instruments.

W. C. Handy was the first person to publish blues as printed sheet music. He composed an electioneering song, “Mr. Crump,” in 1909 and published it as “Memphis Blues” in 1912. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” published in 1914, though not a strict 12-bar song, brought the blues its first large audience, and helped generate an interest in the music. Many factors contributed to the growth of the blues. One was the popularity of the guitar, especially the 12-string guitar, which was brought up from Mexico to Texas and spread eastward. Another was the Hawaiian slack-key guitar, which was tuned to an open chord and played by sliding a metal bar up and down the strings. With the open tuning, the blues singer could play the melody using the altered tones of the vocal scale and work out a harmonic accompaniment on the lower strings. This led to various tunings and the slide or bottleneck styles of blues. Guitars were portable and fairly inexpensive, and could be bought mail-order or made from kits.

The blues guitarist aimed to imitate the blues singer on the guitar. This was done by playing “blue notes”—flattened notes, especially those on the third or seventh degree of the scale. To do this, the guitarist bent or choked the strings, or slid an implement such as a knife, bottleneck, or pick on the strings to produce a blue tonality. Many musicians made their own guitarlike instruments out of a cigar box, a plank, and a couple of strings or broom wires. The harmonica was also a popular blues instrument, more portable and less expensive than the guitar.

Other characteristics common to blues instrumentation included the cross-playing of the harmonica (playing in a key different from the one in which the instrument is tuned); the percussive staccato of the piano keys—the left hand playing rolling bass figures, the right hand playing melodic sequences; and back-beat drumming.

The popularity of African-American vaudeville added to the interest in the blues. The first decades of the 1900s were a period when entertainment by and for African-Americans thrived throughout the U.S. Many blues musicians travelled with jug bands, string bands, African-American minstrel shows, and African- American circuses. Among the musicians who first performed the blues in travelling shows were the stage singers Ma Rainey and Bessie MITH, and accompanists such as TAMPA RED, Thomas DORSEY (“Georgia Tom”), and Lonnie Johnson. Most experts agree that “Crazy Blues,” by blues singer Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, was the first commercially recorded blues record. Produced in 1920, “Crazy Blues” sold 75,000 copies within a month of its release and appealed to African-American and white audiences alike. Women artists had a high profile in the early days of the blues, both instrumentalists, such as MEMPHIS MINNIE, and singers, such as Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Mamie Smith, Lovie Austin, Victoria Spivey, and Ida Cox. Unfortunately, with the demise of vaudeville, interest in “old-fashioned” women blues singers waned, and the blues became an almost exclusively male domain.

By the 1920s, the recording industry was eager to market music to African-Americans. In the mid- and late 1920s, talent scouts with the labels Paramount, Columbia, and Okeh travelled from Chicago and New York to cities such as Memphis, Dallas, Atlanta, and Jackson, Mississippi, to record regional musicians.

The first Southern blues guitarist and singer to realise commercial recording success was not from the Mississippi Delta, but from Texas. Blind Lemon Jefferson recorded in 1926, after a music-shop owner heard him playing and singing on the street in Dallas and sent him to Chicago to record. Jefferson’s influential recordings were played all over the South and sold well. Over the next six years, hundreds of solo artists and small groups made commercial recordings of “country blues.”

Among those recorded in the first years were musicians Texas Alexander, Tommy Johnson, Charley Patton, Willie Brown, and Son House. The records made their names known throughout the South, and other musicians began to emulate them.

The mass recording continued until 1932, when the Depression forced many companies to shut their doors and others to become more selective. Meanwhile, scholars of folk music began to travel through the South making field recordings of musicians, in an effort to preserve the music before it could be affected by outside influences. Father and son, John and Alan Lomax, recorded Leadbelly and others for the Library of Congress beginning in the 1930s. By the late 1930s, recording had had a homogenising effect on the blues, as regional peculiarities gave way to imitation.

Legendary blues guitarist Robert Johnson was influenced by the Delta country blues of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charley Patton, as shown in the recordings he made in the two years before his death in 1938. Many people consider Johnson the most influential of all bluesmen, and many of the songs he popularised, including “Sweet Home Chicago,” “Terraplane Blues,” and “Love in Vain” have become blues standards.

The blues headed north from the South almost as soon as the musical style was “invented.” Southern African-Americans followed what came to be called “the blues route,” travelling by train, foot, boat, and automobile to Memphis, St. Louis, Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, Cleveland, and other northern cities. They migrated in search of a better living, and to escape the racist laws of the South.

The migration north began in earnest during World War I, when jobs became available in the steel mills and stockyards. The style of blues changed with the Northern migration. Folk blues stayed in the rural areas, while guitar-and-piano combos became popular in the cities. These often included a string bass and sometimes brass or reed instruments. Piano players picked up a Boogie-woogie rhythm, spurred in part by the jazz-influenced trio led by Big Joe Turner and Pete Johnson in Kansas City. One reason for the addition of instruments was simply “strength in numbers”—a band could be heard better in a crowded club if it had more instruments.

The formation of larger bands also reflected the blues’ natural growth. Once blues artists achieved a degree of technical prowess, they could expand their sound by adding instruments and increasing the possibilities. Chicago, which had a large African- American population (109,000 in 1920), was especially important in the development of the blues. The style of blues that developed in Chicago was considered brash, since those musicians who headed north were generally younger than those who stayed in the South. Their urban blues style was consider- ably louder than the country blues that was popular down South. The performers often played in noisy clubs and, along with jazz musicians, were among the first to adopt electric instruments and amplifica- tion in the late 1930s.

Singer and guitarist Big Bill Broonzy was one of the first of the great Chicago blues musicians, a prolific songwriter who made some 260 recordings. The musicians who followed Broonzy in Chicago are a Who’s Who of electric blues. Many gained initial exposure in the backing band of the most important among them, Muddy Waters. Buying his first electric guitar in 1944, Waters took amplification beyond the mere raising of volume. He used it to make music that was raw, ferocious, and physical, setting the standard not only for the urban blues that followed but the rock guitar heroes of the 1960s and beyond. His original compositions became essential material for every aspiring blues band, as did emulation of the sound he used when playing these and older blues standards. Other blues artists who made Chicago their home included Tampa Red, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie DIXON, MEMPHIS SLIM, Freddie KING, Sonny Boy WILLIAMSON, LITTLE WALTER Jacobs, Elmore James, Bo DIDDLEY, Buddy GUY, Otis SPANN, Jimmy Dawkins, Otis Rush, Magic Sam, and Jimmy REED.

Blues musicians also headed to the West Coast, especially during World War II, when jobs in factories and defence plants led to another large African-American migration. Notable among the California transplants was Texas guitarist T-Bone Walker. The blues played in California was distinctly urban and somewhat more flamboyant than that played elsewhere. Blues bands on the West Coast had more of a jazz influence, and the bands sometimes included horns. Other musicians known for the recordings they made in urban areas include John Lee Hooker in Detroit, Albert KING in St. Louis, Guitar Slim in New Orleans, and Bobby “Blue” Bland, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and Lightnin’ Lightnin’ HOPKINS in Houston. In the years following World War II, urban blues began to evolve toward R&B.

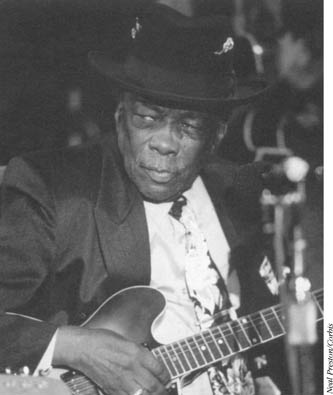

A grand old man of blues, John Lee Hooker was featured on

British television (above) in the early 1990s.

After the war, there was a lot of talk about the death of the blues. When Leadbelly died in 1949, he was widely mourned as “the last of the blues singers,” and when Big Bill Broonzy went on tour in Europe he was widely regarded as a trace of a vanishing tradition. During the 1950s, just as blues musicians were beginning to lose their core African-American audience to R&B, there was an upsurge in interest in the blues among whites (which had the side-effect of hastening the African-American exodus). Soon Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf were playing for white college audiences and European festival crowds, B. B. King was performing at huge rock concerts, and white American musicians were travelling to the South to meet “undiscovered” blues artists. In the 1960s came the British invasion, with Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, John Mayall, and many others declaring their loyalty to American electric blues and proving it by recording blues songs. Television broadcast the blues, especially blues played by young white musicians, to a large audience. American guitarists such as Lonnie Mack, Duane Allman, and Mike Bloomfield began studying the old masters and introducing white teens to the blues.

Meanwhile, country blues was “discovered” by white folk music fans who saw the musicians as honest, earthy, and anti-establishment. But these fans did not want to hear what the blues had evolved into. They wanted to hear traditional blues. By the 1950s, the folk-blues revival was in full swing. Big Bill Broonzy put away his electric guitar and became a country blues singer. Sonny TERRY and Brownie McGhee left the Carolina Piedmont for a gig on Broadway. Musicians such as Mississippi Fred McDowell and Mance Lipscomb who had never recorded before or earned a living as professional musicians, found sudden fame.

During the 1980s, Robert CRAY, Z.Z. Top, Stevie Ray Vaughan and other musicians kept the electric blues alive, while traditional country blues gained in popularity as younger music fans, turning away from the pop world’s predilection for synthesizers and dance music, developed an interest in “roots” music. Taj Mahal and Ry COODER were blues musicians who studied the folk-blues style in the 1960s and still perform today. At the end of the century, the blues audience continues to grow, as young fans throughout the U.S., Europe, and Japan rediscover the music.

Today, many cities have blues societies that put on annual festivals devoted to the blues. Blues music has its own American awards, the W. C. Handy Awards, and its own categories in the Grammy Awards. Labels such as Alligator, Antone’s, Malaco, and Rounder release new blues recordings, while Specialty and others reissue old ones. Both traditional and contemporary blues musicians have found devoted fans. Popular blues artists performing today include many of the old guard, such as B. B. King, Charlie Musselwhite, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Koko Taylor, and David “Honeyboy” Edwards, alongside younger keepers of the flame such as Robert Cray, Joanna Connor, Lucky Peterson, Kenny Neal, Lonnie Shields, Lonnie Pitchford, and Katie Webster.

The legacy of the blues can be heard not only in the music of contemporary blues artists but in other forms of American music. Without the blues, there would be no jazz, no R&B, no rock’n’roll, no soul, no gospel, or rap. Country and bluegrass music reflect a blues influence, inherited from white country blues singer Jimmie RODGERS and others. Classical composers such as George GERSHWIN and Aaron COPLAND incorporated the blues into some of their intrinsically American works.

The blues has become so much a part of American culture that John Lee Hooker advertises Pepsi, and Bo Diddley appears in the Macy’s chain store Thanksgiving Day Parade. The corporate establishment has embraced what was once a deeply anti- establishment form of music that had its origins in the suffering of African-Americans, and helps to make the blues known and appreciated all over the world. However, some people feel that this has made the blues formulaic, sacrificing the variety and subtlety of earlier forms for commercial acceptance.

Daria Labinsky

SEE ALSO:

BOOGIE-WOOGIE; COUNTRY; FUNK; GOSPEL; JAZZ; JAZZ ROCK; POP MUSIC; RAP; ROCK MUSIC; ROCK’N’ROLL; SOUL.

Cohn, L., ed. Nothing but the Blues: The Music and the Musicians

(New York: Abbeville Press, 1993);

Collis, John. The Blues: Roots and Inspiration (New York: Hyperion, 1995);

Lomax, A. The Land Where the Blues Began

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1993);

Rowe, M. Chicago Blues: The City and the Music

(New York: Da Capo Press, 1979).

Roots ‘n’ Blues: The Retrospective 1925–50;

The Sounds of the Delta;

Blues Masters, Vols. 1–14, includes the following previously

released albums: Blues Originals;

Blues Revival; Blues Roots; Classic Blues Women; Harmonica

Classics; Jump Blues Classics; Memphis Blues;

Mississippi Delta Blues; More Jump Blues; New

York City Blues; Post-Modern Blues; Post-War Chicago

Blues; Slide Guitar Classics; Texas Blues; Urban Blues.