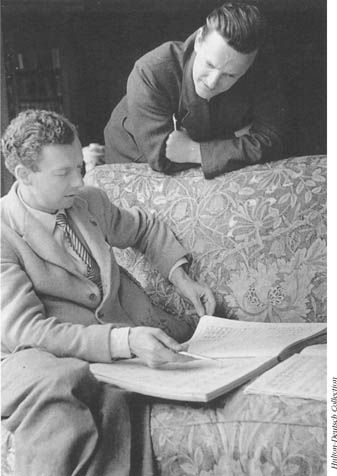

Benjamin Britten (left) and Peter Pears during rehearsals for The Rape of Lucretia at Glyndebourne, England.

Alongside Edward ELGAR, Benjamin Britten is probably the most celebrated British composer of the 20th century. He was born in Lowestoft, a small seaside town on the east coast, on November 22, 1913—an auspicious day, for it is Saint Cecilia’s Day (Saint Cecilia is the patron saint of music).

Britten’s mother, herself a gifted musician, was quick to recognise and encourage her young son’s remarkable gifts. From the age of five, he had piano and viola lessons and began to write short pieces of music. During his teens, he took lessons from, among others, the English composer Frank Bridge (1879–1941), and completed his formal studies at London’s Royal College of Music.

The adult Britten rapidly made a name for himself with early works such as his song cycle Our Hunting Fathers (1936), a piece that set the words of his friend the poet W. H. Auden to music. He also gained recognition with several musical scores specially written for government-sponsored documentary films. An affectionate tribute to his former teacher, Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, introduced his music to a worldwide audience when it was first performed at the International Salzburg Festival in 1937. Upon hearing this work, composer Aaron COPLAND described it as “a knock-out.”

Two years later, Britten sailed for America, accompanied by Auden and the renowned tenor Peter Pears (1910–86)—a lifelong collaborator and partner for whom Britten wrote many outstanding works. Upon arrival in New York, the trio joined an artists' commune, and, while there, Britten demonstrated his love of writing for voice with some striking new pieces, including the song cycle, Les Illuminations (a musical setting of poems by the 19th-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud), and a short opera, Paul Bunyan (inspired by American folklore).

When war broke out in Europe later in 1939, Britten became a conscientious objector—rejecting the idea of fighting and killing on moral grounds. However, in 1942 he decided to return home in order to “do his bit” for his country. Back in England, Britten spent much of his time giving concerts and recitals, but he also found time to write his atmospheric work Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings (1943)—this work consists of settings of poems by Tennyson, Blake, Keats, and other English poets. He also began work on another opera, commissioned by the American Koussevitzky Foundation, which was to prove the real turning point in his life. This work, entitled Peter Grimes (1945), was also to be a turning point in the history of English opera.

The story of Peter Grimes, based on a grim, powerful poem by writer George Crabbe, concerns a strange, solitary fisherman (Grimes) who is victimised by the local community and finally drowns himself. The opera was first performed at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre in June 1945, and was hailed as the greatest opera by an English composer for over 200 years. Britten’s strong feeling for the sea was one aspect of the opera that caught the public’s imagination, and the “Four Sea Interludes” from Peter Grimes has since become a popular concert piece in its own right.

Benjamin Britten (left) and Peter Pears during rehearsals for The Rape of Lucretia at Glyndebourne, England.

Peter Grimes confirmed Britten’s reputation as a great operatic composer, and his operas and choral pieces were to form the most important part of his work. Albert Herring (1947) is a light-hearted comedy, far removed from the tragic world of Peter Grimes. Billy Budd (1951), based on the novella by Herman Melville, takes place on board a British warship during the Napoleonic Wars, and focuses on the injustice and brutality of life aboard ship at that time. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (I960) captures all the magic and comedy of Shakespeare’s play. The Turn of the Screw (1954) and Owen Wingrave (1971) are two chilling ghost stories based on the work of Henry James, and Death in Venice (1973) was based on a story by the German writer, Thomas Mann.

Britten was also interested in types of musical theatre originating from other cultures and eras. Noye’s Fludde (1958), Curlew River (1964), and The Burning Fiery Furnace (1966) are all small operas that contain echoes of European medieval “miracle plays,” and Japanese Noh theatre. He also wrote for children’s voices, as in Let’s Make an Opera (1949), which included elements of audience participation.

Many of Britten’s post-1948 works were written for staging at the Aldeburgh Festival. Soon after the success of Peter Grimes, Britten decided to stage a musical festival at Aldeburgh, a few miles down the coast from his birthplace in East Anglia. The festival took place in the summer of 1948, and thereafter became an annual event. Although perhaps overshadowed by his operas, a number of impressive concert works were composed by Britten throughout his career, and Aldeburgh provided a showcase for them. Such works included The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra (1946), a musical story that introduced children to orchestral instruments; the choral Spring Symphony (1949); and the deeply moving War Requiem (1961), written to commemorate the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, which had been destroyed by bombs during World War II.

In addition to composing, Britten was a fine conductor and pianist—often accompanying Pears on intelligent interpretations of songs by Schubert and other composers. He consistently undertook extensive concert tours worldwide, while the success of the Aldeburgh Festival attracted many famous performers and composers—among them the Russian cellist Mstislav ROSTROPOVICH, for whom Britten wrote the Cello Symphony (1963).

As a composer, Britten was not daringly advanced compared to some of his contemporaries. What he did have, however, was a gift for giving conventional instrumental and vocal sounds and harmonies a surprising new twist, or the musical equivalent of viewing familiar scenes or pictures in a distorting mirror. This talent gave Britten’s music a much more cosmopolitan and internationally appealing sound than that of many other English composers. In 1976, not long before he died, he was made a lord of the realm, the first musician to be given such an honour.

Alan Blackwood

SEE ALSO:

FESTIVALS AND EVENTS; OPERA; VOCAL AND CHORAL MUSIC.

FURTHER READING

Cooke, M., and P. Reed. Benjamin Britten: Billy Budd (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993); Evans, P. The Music of Benjamin Britten (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Choral and orchestral works

Cello Symphony; A Ceremony of Carols; Sinfonia da Requiem; Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge; War Requiem; The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.

Opera and other stage works

Albert Herring; Billy Budd; Death in Venice; Gloriana; A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Noye’s Fludde; Owen Wingrave; Peter Grimes; The Rape ofLucretia; The Turn of the Screw.

Song cycles (with orchestra or piano)

Our Hunting Fathers; Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo; Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings.