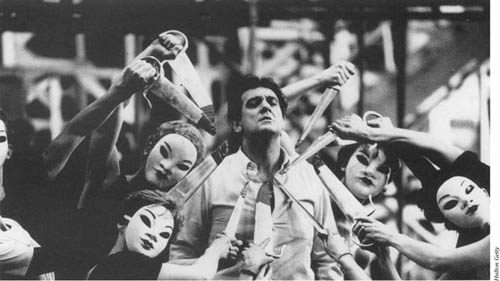

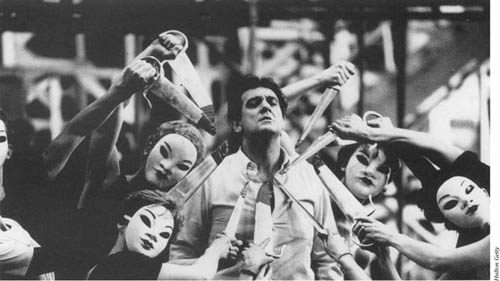

Famous Spanish tenor Placido Domingo in rehearsal for a 1984 production of Puccini’s final work, Turandot, which has become a standard of the opera repertoire. The opera, like Verdi’s Aida, is often performed in large arenas.

The 19th century saw a tremendous development of the operatic repertoire. There was an appetite for new pieces throughout the period, and this creative surge produced the core works of the modern repertoire. Nearly all the operas in performance in 1900 were less than 100 years old, and in the early part of the 20th century, composers struggled to add contemporary masterpieces to those of the past. In the latter part of the century, the impulse has been to return to the 19th century and earlier to revive works outside the standard repertoire.

The leading opera composers at the end of the 19th century were Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner, and in the early days of the new century two people inherited their mantles: Giacomo PUCCINI became the leading figure of the Italian school, and Richard STRAUSS of the German. Puccini is perhaps the most popular of all operatic composers, and he wrote little music that was not for the stage. His most famous opera La bohème dates from 1896, but Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904), La fanciulla del West (1910) and Turandot (1926) are 20th-century master-pieces. Puccini’s operas are generally based on popular plays of the time, or in the case of Turandot, a play by the 18th-century Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi. The themes are the usual operatic ones of love, sex, and death, and the pieces are dramatic, theatrical, and meticulously planned, containing a combination of the intimate and the spectacular. Puccini employs an enormous range of orchestral colour, and the sumptuous orchestral sound and glorious vocal lines have given him wide popular appeal. Other Italian verismo (realist) composers of the late 19th century, Pietro Mascagni, Ruggiero Leoncavallo, and Umberto Giordano, continued to compose well into the new century, but are remembered more for their earlier operas.

Richard Strauss is the natural successor to Wagner, but he also differs from him quite radically. Strauss used Wagnerian-type motifs in his operas, but with Salome (1905) and Elektra (1906–08), his musical style moves on from Romanticism to a greater use of dissonance. Strauss’s operas, like Wagner’s, differ from traditional Italian opera in several ways: although there are big solo scenes, there are no real arias, and the closer equality of voice, orchestra, and drama propels the score. But, in these operas, Strauss is more concerned with psychological drama, although he later retreated from the advanced music of Salome and Elektra to a sweeter musical style. He also turned back to 18th-century story lines for Der Rosenkavalier (1910) and Capriccio (1941), to a fantasy fairy tale for Die Frau ohne Schatten (1917), to the Vienna of the 1860s for Arabella (1932), and to his own home life for the “opera domestica” Lntermezzo (1923). Strauss’s collaboration with librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal gave exceptional dramatic credibility to many of the operas, and the supremely gratifying roles for women express his “love affair with the female voice.”

Psychological intensity is a feature of operas written by composers involved in the dramatic changes that affected music in the period before World War I. Claude DEBUSSY’S wonderfully evocative Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) overlays a close observation of speech rhythms with continuous streams of shifting orchestral colours. The characters have past histories that are merely hinted at, and this lack of information matches the interplay of strong emotions rarely spoken out loud. A tense undercurrent of emotional confrontation similarly pervades Béla BARTÃk’S setting of the legend of Bluebeard’s Castle (1911), although the music is massive and more brilliant.

Sergey PROKOFIEV wrote a number of operas but only two have remained in the repertoire. The Love for Three Oranges (1919) is an eccentric allegory with nonstop, often farcical action throughout. In The Fiery Angel (1923) the story is equally allegorical but the tone of the opera is much more emotionally charged and the vocal lines are intensely lyrical. This emotional intensity is even more extreme in the operas of Alban BERG. The music is composed within a quite broad interpretation of serialism, and uses sprech-stimme—a form of delivery between speaking and singing—to convey the characters’ intense feelings. Berg’s opera Wozzeck (1921) is about a man’s struggle to survive physically and emotionally, and the unfinished Lulu (begun in 1928, but not performed in its completed form until 1979) has a theme of overpowering eroticism, ending in Lulu’s death at the hands of Jack the Ripper. Both operas show an awareness of the new art form of the cinema, with the use of numerous short scenes, and Lulu actually has a scene incorporating the use of film. Arnold SCHOENBERG’S unfinished opera Moses und Aron (1932) is also written in 12-tone technique and deals with God’s promise to man.

Famous Spanish tenor Placido Domingo in rehearsal for a 1984 production of Puccini’s final work, Turandot, which has become a standard of the opera repertoire. The opera, like Verdi’s Aida, is often performed in large arenas.

High seriousness is a feature of the major works of this period. Ferruccio Busoni’s Doktor Faust (1916–24, unfinished) is based on the Faust legend and incorporates elements of the old Germanic puppet plays and of Goethe’s play to produce a profound and mysterious masterpiece which ranges widely in style. Hans Pfitzner’s Palestrina (1917) and Paul HINDEMITH’S Mathis der Maler (1934) both investigate the artist’s place in society, but in totally contrasting styles.

The Czech composer LEOS JANÂCEK wrote operas in which short, passionate, and highly melodic musical ideas are combined with intensely powerful expressions of heightened emotion, delivered in a style of “speech-melody” based on the speech patterns and inflections of the Czech language. Jenufa (1894–1903) only reached the stage in Prague in 1916 when the composer was 60; in the remaining 12 years of his life he produced five more operas, including Katya Kabanova (1921), The Makropoulos Case (1926), and the unfinished From the House of the Dead (1927).

The reaction against Romanticism also manifested itself in works of social realism. Ernst Krenek’s jazz-influenced Jonny spielt auf (1925) was a popular opera at the time, but the most famous and effective pieces in this idiom came from the collaboration of Kurt WEILL with the writer and polemicist Bertolt Brecht. Popular music, jazz, and dissonant classical styles give a striking momentum to hard-hitting drama in The Threepenny Opera (1928) and The Rise and Fall of Mahagonny (1929).

Initially, the Soviet Union also embraced social realism. Dmitry SHOSTAKOVICH’S opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1932) had 83 performances in Leningrad and 97 in Moscow before Joseph Stalin saw it in 1936. Dismissed by him as “chaos instead of music,” this gripping piece was not staged again until the 1970s. A story of devil possession and religious mania, Sergey Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel (1919–27) suffered a similar fate, not being performed again until 1954. His lyrical opera War and Peace (1941–43) also took 15 years to reach the stage.

One of the most operatically prolific and often-performed composers of the late 20th century is Benjamin BRITTEN. He chose to set clear narratives, often depicting the outsider or dislocated personality within a closed society. Peter Grimes (1945) is the most notable example of this, although Owen Wingrave (1970) draws on a similar theme. Loss of innocence is the main preoccupation of Billy Budd (1951), The Turn of the Screw (1954), and Death in Venice (1973). Britten displayed one of the sharpest theatrical and dramatic talents since Puccini, and his broadly tonal musical style made these pieces very approachable.

Mozart, Verdi, and Tchaikovsky are obvious influences on Igor STRAVINSKY’S The Rake’s Progress (1951), but they add a wonderful variety to the composer’s neoclassicism and also enhance the story, which was written by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, and is based on Hogarth’s series of paintings of the same name (1735).

Michael TIPPETT was one of the few 20th-century composers who have written their own words. The operas A Midsummer Marriage (1952), King Priam (1961), and The Knot Garden (1969) have original and individual music that matches the richly imaginative and dreamlike qualities of the narrative. Hans Werner HENZE is one of a number of composers who took up the expressionistic idiom of Berg. Boulevard Solitude (1951), a modern version of the story of Manon Lescaut, his masterpiece The Bassarids (1965), and Venus and Adonis (1997) are among many operas he has written that have strong drama matched by luxurious orchestral writing.

The politicisation of the arts in the 1960s gave rise to new theatrical forms and the acceptance of more recent developments in music. Luigi NONO’S opera Intolleranza 1960 (1961) is a critique of capitalist society that incorporates electronic taped music. Henze’s conversion to revolutionary socialism found an effectively aggressive expression in We Come to the River (1976). Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten (1964) is perhaps the most profound and challenging opera of its time, combining multiple and harrowing dramatic strands with sophisticated use of considerable orchestral forces.

If some of the more advanced composers of the latter part of the 20th century returned to opera to express themselves, it is perhaps because this hybrid form can encapsulate so much. The mythical qualities of Harrison Birtwistle’s The Mask of Orpheus (1986) and the religious ones of Olivier MESSIAEN’S St. Francis of Assisi (1983) find a stimulating home alongside the spectacle, ritual, and synthesis of music and religion within Karlheinz STOCKHAUSEN’S sevenopera cycle, Licht (begun in 1977). They all aim to achieve an almost medieval sense of grandeur. Other composers have created operas that question the very nature of operatic form: Maurizio Kagel’s Staatstheater (1971) and Luciano Berio’s Un re in ascolto (1984), for example, explore both the meaning and the structures of the theatrical, while György LIGETI’S Le grand macabre (1978), with its overture for motor horns, almost tears open the theatre in its declaration of the end of the world.

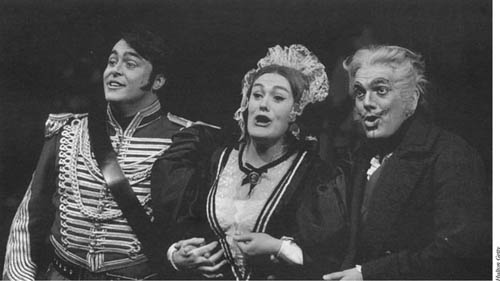

A star-studded cast for Donizetti’sTa Fille du Régiment in 1966 with a young Luciano Pavarotti, Joan Sutherland, and Spiro Malas. Pavarotti had to produce a virtuoso nine high Cs one after the other in the finale.

The European repertoire was the mainstay of the opera houses in the United States in the earlier part of the 20th century. Later, a national style found some expression in Paul Hastings Allen’s The Last of the Mohicans (1916), but Virgil THOMSON’S Four Saints in Three Acts (1934), with a text by Gertrude Stein, and Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock (1937) are rather more original attempts to create a contemporary opera. The most famous, successful, and socially aware work of the time, written and orchestrated with great brilliance, was George GERSHWIN’S Porgy and Bess (1935). Porgy and Bess, however, points in the same direction as Kurt Weill’s American compositions—Lady in the Dark (1941), Street Scene (1947), and Lost in the Stars (1949)—straight to Broadway. This line, including Leonard BERNSTEIN’S West Side Story (1957) and Stephen SONDHEIM’S Sweeney Todd (1979), overshadows the more overtly operatic pieces from Gian Carlo MENOTTI, if not the richly orchestrated nostalgia of Vanessa by Samuel BARBER (1958). But another musical development, essentially originating in the U.S., has had worldwide attention. Minimalism, which achieves a meditative, static quality with the use of hypnotic repetition of simple elements, has given rise to a number of highly successful works for the stage. Philip GLASS’S Satyagraha (1980), with a Sanskrit text, and Akhnaten (1984), with words in ancient Egyptian, have created a popular following with their mesmeric power, and John Adams’s Nixon in China (1987) and The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) bring contemporary subjects to the operatic stage.

The second half of the 20th century also saw a resurgence of interest in operas from the more distant past. The operas of the 17th-century Monteverdi and Cavalli have been revived, and those of the 18th-century Handel are at last finding a permanent place on stage. The lesser works of the early 19th-century composers Rossini and Donizetti have received close attention, and the first operas of Verdi have rightly been recognised as vigorous and original masterpieces.

With the new adventurousness of operatic production comes the hope of incorporating more contemporary works into the repertoire. Over the past century, the importance of the stage director and the designer has increased dramatically. Great visual artists such as Picasso, Bakst, Dali, Chagall, and Hockney have become involved in theatrical design, and the purely stage aspect of opera has become more important. At the end of the 20th century, directors such as Peter Sellars and David Alden reaffirmed opera’s links with contemporary theatre. For opera to remain the overwhelming experience that synthesises music, voice, drama, and spectacle, it must achieve a an image that attracts ordinary people—rather than being a vehicle for a stable of international stars who travel the world delivering the culture of past times.

Stuart Harling

SEE ALSO:

EXPRESSIONISM IN MUSIC; IMPRESSIONISM IN MUSIC; MINIMALISM; OPERETTA.

FURTHER READING

Conrad, Peter. A Song of Love and Death (London: Hogarth Press, 1996);

Douglas, Nigel. The Joy of Opera (London: André Deutsch, 1996);

Lindenberger, H. Opera in History: from Monteverdi to Cage (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Bartok: Bluebeard’s Castle; Berg: Wozzeck; Britten: Billy Budd; Janâcek: The Cunning Little Vixen; Prokofiev: The Love for Three Oranges; Puccini: Turandot; Schoenberg: Moses und Aron; Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier; Weill: The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.