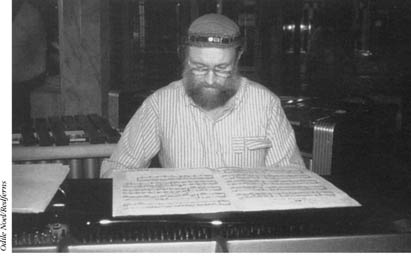

American minimalist Terry Riley being filmed for television in a restaurant in Notting Hill, London, in spring 1989.

Minimalism is a style of composition in which as much musical effect as possible is gained from as little musical material as possible. It is based on the repetition of motifs (simple, short snatches of tune) whose melodic and rhythmic characteristics may be exploited to achieve a multilayered effect of considerable complexity.

In its narrowest sense, minimalism refers to the explorations of a group of American composers of the 1960s and 1970s. Although there are some historical parallels, the ideas of the group were largely influenced by the possibilities of electronic music and the philosophy of Eastern music. Minimalism uses the antithesis of the traditional approach to developing a motif. In minimalist music, the opening statement changes so slowly (if at all) that the effect is not of development but of stasis, and development through the piece is simply not regarded as central to the structure as it was in classical music, so that the listener may feel that he or she has ended back at the beginning.

Minimalist music is closely connected with both rock and Eastern music. From rock, minimalism incorporates the use of ostinatos (the persistent repetition of small rhythmic or melodic ideas), clear and simple phrase structure, and a fundamental concern with rhythm. It reflects Eastern music in its static quality and the occasional use of a drone, and its basic hypnotic quality established through repetition. This last characteristic highlights minimalism’s relationship with the hallucinogenic, consciousness-altering drug culture—another connection with rock music.

Another aspect of minimalism, explored in the first place by LaMonte Young (b. 1935), is an interest in pure intonation and in the harmonic series. Intonation has been an interest of theoreticians for centuries, and centres on the paradox that, if the constituent intervals of the octave are tuned absolutely purely, the octave itself will be out of tune. It is possible for unfretted string instruments or unaccompanied singers to perform in pure intonation, but keyboards and fretted instruments have to be “tempered” (made slightly out of tune). However, with the advent of the synthesizer, pure tones and the whole overtone series (the series of notes produced by fractions of the frequencies of tones) could be generated. Pieces of music could be written with long tones sustained on the synthesizer with the addition and subtraction of harmonics.

American minimalist Terry Riley being filmed for television in a restaurant in Notting Hill, London, in spring 1989.

LaMonte Young studied at the Darmstadt School with Karlheinz Stockhausen, and there encountered the works of John Cage. Later, he also studied classical Indian music with Pandit Pran Nath. He combined these influences to create a kind of musical event, using electronic or vocal drones and combining these with light shows to produce a prolonged meditative ambience. After 1964, Young treated all his performances as integrated parts of his life’s work, entitled The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys.

Terry Riley (b. 1935) was one of the first composers to work with the idea of continuously repeated melodic fragments. He began with short phrases on tape (“tape loops”), which could be played over and over, as in Mescalin Mix (1963). He then applied the concept to live performance, resulting in the dramatic In C (1964), which consists of 53 motifs that can be played by any number of players on any type of instrument. Each player is directed to enter the piece at will, and to play each motif as many or as few times as desired. In this way, In C combines two important musical innovations of the second half of the 20th century: aleatory music and minimalism. The result was a spectacular collage of sound.

Riley’s Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band (1967), for soprano saxophone and electronic keyboard, shares many characteristics with Rainbow in Curved Air (1969). Both appear to be assembled from multiple layers of tape loops, some moving in 32nd notes, some in 16ths, some in 8ths, and some in quarters. Both works borrow from several different styles of music, including jazz, popular, contemporary classical, and Eastern. This fusion of various influences is another characteristic of many later 20th-century compositions.

Steve Reich brought another element to minimalism. He studied African drumming in Ghana and was more interested in using instruments, such as percussion groups, than in electronic sound production, although he too experimented with tape loops. In his early works It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1960) he introduced “phase shifting”—playing short tape loops of speech together but at different speeds. In 1967, he further developed this technique with Piano Phase, for two pianos, and with Violin Phase, for four violins. In these pieces, the musicians play the same musical phrase but move in and out of synchronisation. These pieces were followed by others based on phase shifting, including Phase Patterns (1970) and Clapping Music (1972).

In Different Trains, a work for tape and string quartet, Reich incorporated recorded voices of railway workers from the 1930s and 1940s. This piece aimed to correlate the sounds of the composer’s Jewish childhood with the sounds of the trains in Europe in the 1940s that transported Jews to concentration camps.

With Music for 18 Musicians (1976) Reich began to incorporate more traditional elements in his music, including larger bodies of instruments and an interest in harmony and melody that had been absent from his earlier work. The Desert Music (1982), which incorporates orchestral and choral elements, is one example of this later style.

Philip Glass was influenced by Indian music and its rhythms after meeting Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar in the 1960s. His early minimalist work Two Pages was purely experimental, but Music in Fifths (1969) introduced an “additive rhythmic process.” This consists essentially of expanding and contracting a basic rhythmic statement.

In his later works, Glass developed an interest in harmony and began writing operas. His Einstein on the Beach (1975) takes the minimalist principle into opera in that it is largely static and dispenses with narrative. In Akhnaten (1983), the story of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh, Glass produced a more lyrical and structured piece which strongly reflects his interest in myth and religion. In addition, Glass was also a highly acclaimed film composer, notably with his scores for Koyaanisqatsi (1983) and Mishima (1985).

A later composer who also took minimalism into opera was John Adams (b. 1947), who was interested in portraying contemporary events. Nixon in China (1987) tells the story of the former American president’s visit to China in 1972, and The Death of Klinghoffer (199D deals with the Palestinian hijacking of the ship Achille Lauro. Adams’s operas were both more lighthearted and more psychologically subtle than those of Glass, and his operatic recount-ings of contemporary events attracted large and enthusiastic audiences.

Traces of the concept of minimalism can be found in other contemporary composers as diverse as Estonian Arvo Part, who used the timeless, repetitive sounds of chant to produce his profoundly religious music, and English John White, who based his prolonged works on number systems.

Richard Trombley

SEE ALSO:

ALEATORY MUSIC; DARMSTADT SCHOOL; ELECTRONIC MUSIC; FILM MUSIC; ROCK MUSIC

Mertens, Wim. American Minimal Music: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass (New York: Broude, 1983);

Schwarz, K. Robert. Minimalists (London: Phaidon, 1996).

Philip Glass: Koyaanisqatsi; Steve Reich: Come Out; Terry Riley: Rainbow in Curved Air.