Folk music is the music of the common folk, traditionally played on acoustic instruments. To define it any more completely invites argument. Charles Seeger, a Harvard musicologist and patriarch of one of America’s most prominent folk families, once wrote an essay, “The Folkness of the Non-Folk and the Non-Folkness of the Folk.” In it, he discussed how those who preserve folk are not “the folk.” The true folk have no use for folk art, he wrote, at least not any that is self-conscious enough to call itself that. As folk music was discovered, scrutinised, revived, and occasionally popularised during the 20th century, it changed, and it continues to evolve even today. It remains a source of self-entertainment for ordinary people but also has become an important part of the music industry.

As the fledgling American folk music thrived in the early part of the 20th century, European folk music, which is centuries old, began to fade away between the two world wars. This was due, in particular, to the beginning of cultural homogeneity caused by the influence of the mass media industry.

However, many classical European composers used their native folk music as the basis for works and as subjects of musicological interest. The most important of these was Béla BARTóK, who collected thousands of recordings of Hungarian folk music. Other composers who made extensive use of folk music were Manuel de FALLA, Zoltán KODáLY (who worked with Bartok), Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS, and Witold LUTOSLAWSKI in Europe, as well as Aaron COPLAND and Charles IVES in America. Many of these composers were part of the musical nationalist movement prevalent in the first half of the century.

Folk songs were once defined as songs that had been passed on by word-of-mouth from generation to generation, with nobody knowing who had been the original composer. Today, folk songs tend to be credited to legends, such as Woody GUTHRIE, Pete Seeger, and LEADBELLY, and also to artists of the 1990s, such as John Gorka and Gillian Welch.

Folk in the U.S. is a broad umbrella term that includes types of music—such as bluegrass, country, blues, Cajun and other genres—that have taken on identities of their own. Each type of folk music has influenced the others over the years, as well as having had an impact on popular music; and in turn each type of folk music has been influenced by other types of music. Scholars began chronicling word-of-mouth music during the late 19th century. Harvard ballad scholar Francis James Child was primarily interested in the literary content when he published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, but by identifying 305 “classic” ballads of the English-speaking world, he provided a reference point from which more exploration could begin.

Cecil Sharp performed essential research when he arrived from Britain to travel through the Cumberland Mountains of Kentucky in 1917 and found many English songs in daily use, sounding much the same as they did when they left England. His book English Folk Songs From the Southern Appalachians was published in 1919. Lamar Bascom Lunsford and Robert W. Gordon scoured the Southern mountains, looking for performers and collecting songs. Lunsford founded the oldest festival of folk music and art in the U.S., the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1928. Poet Carl Sandburg was another prominent collector. While doing research for his biography of Abraham Lincoln, Sandburg supported himself by singing folk tunes and also accumulated an important collection of folk music, which he published as The American Songbook. John A. Lomax turned out to be the most influential of the folklorists, and along with his son, Alan, he eventually made thousands of field recordings.

John Lomax began with a fascination for cowboy songs, and in 1912 he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads. Among the songs he collected for that volume was “Home on the Range.” In 1915, he listed seven types of American ballads, originating from miners, lumbermen, sailors, soldiers, railway men, Negroes and cowboys. Radio further boosted interest in folk music in the 1920s, with the Grand Ole Opry, out of Nashville, and the National Barn Dance, from Chicago, boosting many performers to prominence. The Grand Ole Opry was launched in 1925 as the WSM Barn Dance, and its first star was Uncle Dave Macon, who wrote songs with a political bent and played the banjo at a time when the guitar had become the instrument of choice in popular music. He attracted new young pickers to the banjo, setting the stage for its popularity in bluegrass. The department store Sears & Roebuck sponsored Chicago’s National Barn Dance, which offered a variety of musical styles and helped Rex Allen, Gene Autry, Homer and Jethro, Bill MONROE, Jimmy Osborne, and others to gain prominence.

With radio dominating the mass markets and making an immediate impact on record sales, worried record companies began to produce various records for limited audiences, such as African-Americans and “hillbillies,” who weren’t finding much of their own music on the radio. In 1926, the success of Texan Blind Lemon JEFFERSON’S blues recordings opened the door for scores of other blues artists. Okeh Records actively recorded this “race” music, and Ralph Peer was one of its most successful scouts. He was working for Victor Records in 1927 when he found both the CARTER FAMILY and Jimmie RODGERS in the course of four days.

Rodgers was country music’s first superstar. Working for the railway, he learned the blues and the basics of playing guitar and banjo from the African-American labourers, and began singing in a minstrel show. His guitar phrasing was unique—he sometimes used backing groups, such as Hawaiian and Dixieland bands—and he embellished his singing with yodelling.

The Carter Family sang old-time mountain standards and gospel hymns, and featured Maybelle Carter’s guitar as a solo voice. Her guitar style was copied by a generation of musicians, including Woody Guthrie, who also used dozens of Carter Family tunes in composing his own songs.

While Guthrie and Huddie Ledbetter, better known as Leadbelly, deserve the attention they have received as central figures in 20th-century folk, the tunes and words now credited to them actually came from many different sources. Leadbelly was a product of the Deep South and Guthrie of the mid-West Dust Bowl. The two performers rose to prominence in the 1930s at a time when folk music had taken on new credibility. President Franklin Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, offered their personal support in promoting folk music, and Alan LOMAX conjectured, “The reason that [the Roosevelts] were interested in folk music was, first of all, that they were Democrats … and they wanted to be identified with it as a democratic art … They hoped that the feeling of cultural unity that lies somehow in our big and crazy patchwork of folk song, would give Americans the feeling that they all belonged to the same kind of culture.”

Some of John and Alan Lomax’s first field recordings were of Leadbelly, when he was serving time in a Louisiana prison for murder. They took him to New York City in 1935, and while Leadbelly resented seeing headlines calling him a “homicidal harmonizer,” it did serve to put folk music in the headlines, on newsreels and the radio, and in front of millions of Americans. When the Lomax book Negro Folk Songs as Sung By Lead Belly was published in 1936, it offered the first serious, full-length portrait of any folk singer in American literature.

After initial appearances in his prison garb, singing mostly prison-type songs, Leadbelly soon began to appear more stylishly dressed. His performances offered the wide variety of music he had learned while growing up along the Louisiana-Texas border before 1900. Among his most popular songs was “Irene” (later the No. 1 song in America when the WEAVERS recorded their own version of it in 1950). Leadbelly remembered first singing the song in 1908 or 1909 to a favourite niece named Irene, and said he learned the tune from a songster uncle. The uncle, in turn, likely heard it roughly 15 years before as a Tin Pan Alley song sung by Gussie Davis.

Both Leadbelly and Guthrie were adept at taking familiar melodies and adding their own words, producing immediately topical songs that were popular at political rallies and union meetings. Guthrie wrote his songs at the typewriter, and the music was often an afterthought. In fact, in later years he too used the tune of “Irene” in several songs. His “This Land Is Your Land” was penned to the tune of the Carter Family’s “Little Darlin’, Pal of Mine,” which itself was taken from an old Baptist hymn, “Oh, My Livin’ Brother.” Guthrie wrote the song in 1940 shortly after he arrived in New York. It was written as a Marxist reaction to Irving BERLIN’S “God Bless America,” which Guthrie had heard over and over in his travels. When he first wrote the song, it was called “God Blessed America,” with the final line of each stanza “God Blessed America for me.”

Guthrie immediately fit in with New York’s politically active folk singers of the 1930s. He had already donated his time to perform for union workers and migrant workers when he was in California and writing for a Communist newspaper. He, Pete Seeger, Leadbelly, Aunt Molly Jackson, Sonny TERRY and Brownie McGhee, Tillman Cadle, Burl Ives, Josh White, and others, performed for a variety of leftist groups. They linked folk singers and causes in the popular mind, a political and musical association that would continue for decades.

Guthrie, Seeger, Lee Hays, and Millard Lampell formed a folk group, the Almanac Singers, in 1941, touring and playing at political rallies and “hoote-nannies” (a term Seeger and Guthrie learned while touring the Northwest, and which become popular once again in the early 1960s). They disbanded shortly after World War II began, with another band of Almanac Singers taking their place. Guthrie, Seeger, and others founded People’s Songs Inc. in 1946 and published a regular newsletter called The People’s Song Bulletin. It included old and new songs, articles, book and record reviews, and information about festivals and concerts. Its motto was “songs of labour and the American people.” People’s Songs went bankrupt in 1949, but was succeeded by People’s Artists, which presented concerts and gave artists a booking service. It also began publishing the magazine Sing Out!, which survives to this day.

Seeger, Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hillerman formed the Weavers in 1948. They chose their name from a leftist play, but bowed to popular music by releasing a heavily arranged album replete with violins. Seeger defended the orchestrated approach taken on the album by explaining that the Weavers were willing to do almost anything to “make a dent in the wall that seemed to be between us and the American people … we’d now gotten into such a box that we were just singing to our old friends in New York.” The group was tremendously successful, and their success resulted in traditional music being more popular than it had ever been. Just as quickly, however, the door slammed shut.

The Weavers disbanded in 1952, when its members were subjected to the blacklists of McCarthyism. Right-wing reactionaries drove folk music off the radio and out of the nightclubs. However, the foundation for the next revival was laid in 1952, with the release of the multi-album set Folkways’ Anthology of American Folk Music. Much of the recorded folk music available until then—such as Guthrie’s compilation Dust Bowl Ballads—represented the vision of John and Alan Lomax that folk songs were part of an active political programme. This collection of 84 songs on Moses Asch’s Folkways label covered a broad range of traditional material recorded from the 1920s through the 1940s. Music that was originally sung “by folk to folk” took on a new aura, because it was presented on six LPs in the same manner as classical music. It also appealed directly to the romantic revivalists—those folk connoisseurs who believed that the songs were from and about simple, uncomplicated people, close to the soil, who controlled their own culture because they developed and nurtured it themselves.

The romantics saw folk music as a way to return to such a pastoral life. The Kingston Trio launched folk’s popular revival with “Tom Dooley,” the No. 1 song of 1958. “Tom Dooley” was a traditional mountain ballad about a hanging that took place in 1868, and the song was passed down through the years by word of mouth. Not only did it put the Kingston Trio on top of the charts, but it also had the lineage to inspire new would-be folk singers without the political baggage that had sent the last generation underground. While purists complained that the Kingston Trio’s sound was too sanitised, and that they would change the lyrics of traditional tunes to keep them free of political content, their timing was impeccable. The band’s name associated it loosely with Kingston, Jamaica, and calypso, which Harry Belafonte had helped to popularise during the mid-1950s—the group even used a conga drum!

Although the oncoming folk revival was to focus on traditional music firmly planted in the U.S. by the 1920s, the search for deeper roots opened American folk to world music in the second half of the century. The Kingston Trio’s music was carefully arranged, and their delivery well coached, but the trio seemed just amateurish enough to invite imitation. Although their song “M.T.A.,” about a man trapped in the Boston subway system because he doesn’t have a token to get off now seems like a novelty song, it told a story, and would-be folk singers figured they had similar stories to offer. Parents looked at the well-groomed Kingston Trio members and happily bought guitars for their own children. In 1959, the Kingston Trio helped to kick off the Newport Folk Festival, a key venue for the nurturing of traditional music. As the headline group, the trio brought in 15,000 fans.

Dozens of other groups quickly followed, such as the Wayfayers, the Highwaymen, the Brothers Four, the Limeliters, the Tarriers, and the Chad Mitchell Trio. Coffeehouses and folk clubs sprang up across the nation, giving young singers and songwriters plenty of venues in which to perform. Singers who came to the fore included Phil Ochs, Tim Hardin, Joan BAEZ, Tom Paxton, Eric Anderson, Judy Collins, Ian and Sylvia, Dave Van Ronk, and Bob DYLAN.

Like others, University of Minnesota freshman Robert Zimmerman turned his aspirations from rock’n’roll to folk in 1959, calling himself “Bob Dylan” and playing in local coffeehouses. He became obsessed with Woody Guthrie—keeping Guthrie’s biography at his side, memorising Guthrie’s songs, holding the guitar like Guthrie did, and writing one of his first songs about Guthrie. When he learned that Guthrie was confined to a hospital in New Jersey, he tried to call. Since he couldn’t reach Guthrie by telephone, he took off to see him. Dylan literally played at Guthrie’s feet, and, like Paxton, Ochs, and others, he seemed to be cut from the same political cloth as the folk singers of the 1930s and 1940s. He and other young singers went to the South to support civil-rights workers, and they were active in other marches and demonstrations. Pete Seeger was in the middle of this, an active link between the 1940s and 1960s. Seeger had made field recordings for the Lomaxes in the 1930s, then he had travelled throughout America. He had sung with Guthrie in the 1940s, and helped found the Weavers, but he was blacklisted in the 1950s, called before the House Un-American Activities Committee for his supposed communist sympathies. He was reduced to keeping his message alive by appearing mostly on college campuses.

In 1902, the television network ABC began a folk music show called Hootenanny, a word Seeger had helped to put into popular vocabulary. Ironically, Seeger was not allowed on the show because he had been blacklisted. The folk singer and songwriter Judy Collins was among those who organised a boycott of the television show, yet despite this protest many folk performers chose to appear, making it obvious that the folk music community was no longer a single-minded entity.

New York City was the capital of the folk movement. Clubs such as Gerde’s Folk City, The Gaslight, and Café Wha? made Greenwich Village a mecca for young musicians. Every weekend, Washington Square was a virtual outdoor music festival. The ailing Guthrie could be seen and Bob Dylan, whose early songs were true to the left-wing folk tradition, with tunes such as “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall.” Dylan created a broader audience for folk music so that his tunes and other protest songs were recorded by popular singers and groups.

Among the more enduring of these groups was Peter, Paul, and Mary. They made a hit out of Seeger’s protest song “If I Had a Hammer” and remained active in folk into the 1990s, often conducting workshops for young singers. This folk revival was at its zenith in 1963, when Time magazine put Joan Baez on its cover, and an audience of 37,000 turned out for the Newport Folk Festival. But the BEATLES-led “British invasion” began to knock folk out of the limelight shortly after, and in 1965 all sense of unity was shattered. On the last night of the Newport Folk Festival that same year, Bob Dylan showed up on stage backed by an electric band. Seeger reportedly was ready to get an axe and cut the power, rather than see the singer he thought would carry on the tradition of Woody Guthrie be washed into the popular mainstream. Instead, Dylan played two songs, to a mixture of cheering and booing, left the stage, and returned with his acoustic guitar to sing, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

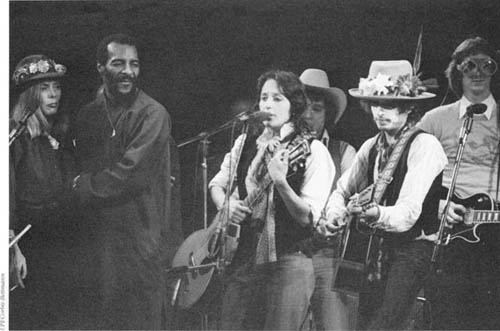

Carrying forward the political tradition of American folk music, 1960s starsJoni Mitchell, Richie Havens, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan, performed in a benefit concert in 1975.

Soon, nearly all the popular folk singers were performing amplified, and even Seeger eventually recorded with an electric band but the music survived. In fact, protest singers were prominent during protests against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Seeger even made it to television, singing his gripping anti-Vietnam War song, “Knee Deep in the Big Muddy,” on the Smothers Brothers show on CBS in 1968. Seeger turned his attention to the environment, specifically to cleaning up the Hudson River, but he never entirely left music. In 1994, he received a Presi-dential Medal of Arts award, and in 1996 he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an “Early Influence.” The following year his album Pete won a Grammy as best traditional folk album.

The influence of Seeger and other folk musicians is widespread in popular music today, where lyrics have considerably more meaning than they did in the early days of rock’n’roll, and rock groups such as U2 have embraced the protest song. Traditional folk music is easy to find, unless you search for it on TV or radio. The artists Indigo Girls, Michelle Shocked, and Shawn Colvin, who won radio air time in the 1980s and 1990s, were the tip of the folk music iceberg. In 1997, Rounder Records released the first of what will be a 100-CD set compiled from Alan Lomax’s field recordings.

Modern folk music performers continue to have a loyal and musically aware audience. Coffeehouses and clubs still cater to folk singers, and the folk tradition is kept alive at numerous festivals, where the audience members are as likely to bring their instruments along as the performers are. The festivals often present singers whose roots go back to the 1960s or earlier alongside any newcomers; for example, Tom Paxton may well be followed on stage by Greg Brown. It would also appear that folk runs in the family. Woody Guthrie’s son, Arlo, recorded a major hit with his talking blues song, “Alice’s Restaurant,” when he was just 19 years old, and he became an active bearer of his father’s torch. Mike Seeger, Pete’s younger brother, is both a fine singer as well as a folklorist/collector carrying on for his father, Charles.

The simplest definition of a folksong is that it stands the test of time, and the same can be said of folk music itself. As the revival of the 1960s was beginning to ebb, Seeger was asked to look into the future and predict the fate of folk. In response he said: “Tradition is still not fully explored, and topical songs are a bottomless well. As long as life moves, music moves; as long as kids are crying, there will be lullabies written and sung.”

Stan Hieronymus

SEE ALSO:

BLUES; CAJUN; COUNTRY; FOLK ROCK; GOSPEL; GYPSY MUSIC; MITCHELL JONI; ROCK MUSIC, U2.

FURTHER READING

Abrahams, Roger. The Smithsonian-Folkways Book of American Folk Songs (New York: HarperPerennial Library, 1995);

Cantwell, Robert. When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996);

Dunaway, David. How Can I Keep From Singing: Pete Seeger (New York: Da Capo Press, 1990);

Palmer, Roy. The Sound of History: Songs and Social Comment (London: Pimlico, 1996).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Peter, Paul, and Mary: Peter, Paul, and Mary;

Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited;

Blonde on Blonde; Arlo Guthrie: Alice’s

Restaurant; Joan Baez: Diamonds and Rust;

Various Artists: A Vision Shared: A Tribute

to Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly;

A Vision Revisited: The Original Performances by Pete

Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Leadbelly.