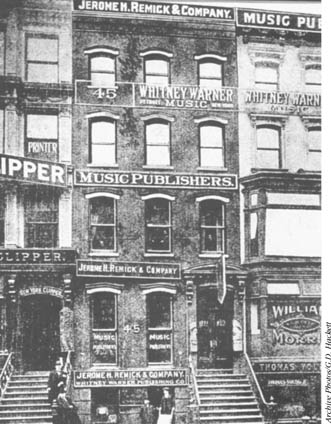

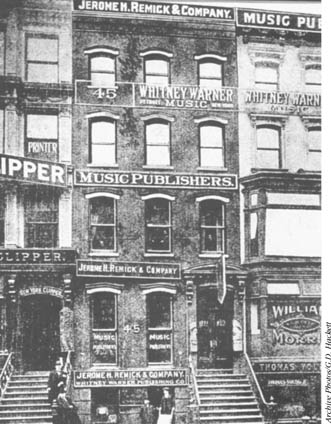

The songwriting factories on New York’s 28th Street—Tin Pan Alley—where many songwriters sold their first songs.

Back in the 1860s sheet music for songs was in great demand. Before the era of television or radio, families made their own entertainment at home in the evenings, often singing around the piano. Popular songs for family singing were Irish ballads like“When You Were Sweet Sixteen,” and melodramatic pieces such as “The Lost Chord.” One of the most popular songs of all was the tearjerker “After the Ball.” The sheet music for this 1892 ballad sold 10 million copies, and fortunately for the composer, Charles K. Harris, he had published the song himself.

Since there was good money to be made from song publishing, New York publishers conducted surveys to discover the public’s tastes, and then commissioned songwriters to fill that need. Audiences across the country would hear the song sung at their local vaudeville theatre, and would then go and buy the sheet music to try it out at home.

By 1900, several important publishers were based on Manhattan’s 28th Street. The cramped offices were partitioned into cubicles with pianos so that the composers and song-pluggers could write and sell their work. There was no air-conditioning, so the windows would be open in summer. A journalist, Monroe H. Rosenfeld, likened the discordant sounds of these well-worn pianos to “tin pans beating.” And so Tin Pan Alley was named—although by the 1920s it had moved closer to Broadway, on 42nd Street.

Once a song was written it had to be sold, and this was the job of the song-plugger. The best way to get it heard by the buying public was to persuade a big-name artist to sing it in vaudeville. One of the biggest names was Al JOLSON, and his greatest hits— “Swanee,” “Sonny Boy,” and “California, Here I Come”—are sung and whistled even today.

Many songwriters received a one-time payment for their songs—it was the publishers who made the most money. So it made sense for a good songwriter to become a publisher himself. As well as Charles K. Harris, other songwriter-publishers were Harry von Tilzer, who wrote “Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie,” and Kerry Mills, composer of “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis.”

The songwriting factories on New York’s 28th Street—Tin Pan Alley—where many songwriters sold their first songs.

Another problem for both songwriters and publishers was the difficulty of getting a royalty payment when their songs were performed in public. In the early years of the 20th century, the composer Victor Herbert successfully sued a New York restaurant for playing his music without payment. Following the Court’s decision in his favour, the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) was founded in 1914 to protect performing rights. ASCAP was then able to license and collect fees from thousands of restaurants and theatres.

The coming of recorded sound in the early part of the 20th century changed the music scene radically. By the late 1920s, sales of records were outstripping those of sheet music, and movies were on the horizon. The first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, featured Al Jolson, who then requested a ballad “that will make people cry” for his second film, The Singing Fool. The songwriters wrote “Sonny Boy” as a practical joke, but Jolson took the ultra-corny song seriously, and it sold a million records as well as a million copies of sheet music.

Between the wars, Tin Pan Alley was dominated by several brilliant composers. Irving BERLIN, a Russian immigrant who became the all-American songwriter, wrote a stream of hits for over 50 years, starting with “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” in 1911. He also became a publisher in the 1920s, and began buying back his own songs. Hits included “Blue Skies” (from The Jazz Singer), “Always,” and “White Christmas.”

George GERSHWIN was a superbly gifted pianist and arranger who could dazzle with a myriad of styles. He also wrote a stream of hits, including “Swanee,” “The Man I Love,” and “Embraceable You.” Cole PORTER’S witty, intelligent lyrics can be heard in “You’re the Top,” “Just One of Those Things,” and “I Get a Kick Out of You.”

In 1911 the publisher Lawrence Wright bought a shop on Denmark Street, just off London’s Charing Cross Road; soon he had acquired and leased the whole block, which also became known as Tin Pan Alley. His hits include “Among My Souvenirs,” written under the pseudonym Horatio Nicholls, and “Don’t Go Down the Mine, Daddy,” which he bought from a street musician following a pit disaster for five pounds and then sold a million copies of it. In 1922, he founded the paper Melody Maker, devoted to popular music.

Noel COWARD challenged American supremacy with love songs such as “Someday I’ll Find You” and “I’ll See You Again,” while also writing satirical lyrics about the British Establishment in songs such as “The Stately Homes of England” and “Mad Dogs and Englishmen.” Jimmy Kennedy kept the song-pluggers busy with “Red Sails In the Sunset,” “South of the Border,” and “These Foolish Things,” plus “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic.”

The heyday of Tin Pan Alley was over by World War II. The 1940s and 1950s were the era of the great musicals. RODGERS and HAMMERSTEIN struck gold with Oklahoma! and Carousel, while South Pacific, in 1949, coincided with the birth of the LP. The 1950s saw hit musicals such as The King and I, Guys and Dolls, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and West Side Story, all packed with memorable singles. Whenever an artist recorded a song, a new orchestration was required, and this provided plenty of work for arrangers and orchestrators who had learned their trade in Tin Pan Alley.

In the 1960s, the need for quality songs that reflected teenage interests was satisfied by former Tin Pan Alley songwriters Al Nevins and Don Kirshner, who formed Aldon Music, one of many publishers based in New York’s Brill Building. Many of the Brill Building songwriters were good performers themselves. The most sophisticated Brill Building partnership was that of Burt BACHARACH and Hal David, whose hits included “Magic Moments,” “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” and “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head.”

However, the market for songwriters was disappearing. The singers of the early 1970s, such as Elton JOHN and James Taylor, wrote their own material. Nowadays, the record and the accompanying video are more important than the song itself, and very few of today’s chart songs are recorded by other performers. The market for sheet music has declined.

The golden age of Tin Pan Alley, with its system of songwriters, was responsible for producing many classic popular songs of enduring quality, which sold millions of copies of sheet music, which remain the standard repertoire of club and cabaret singers.

Spencer Leigh

SEE ALSO:

ARRANGERS; FILM MUSICALS; MUSICALS; POPULAR MUSIC; SINGER-SONGWRITERS.

FURTHER READING

Furia, Philip. The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Greatest Lyricists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Burt Bacharach: Bun Bacharach’s Greatest Hits; Irving Berlin: Annie Get Your Gun; Call Me Madam (soundtracks); Noel Coward: Noel Coward Live in Las Vegas; George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess; Al Jolson: The Best of Al Jolson; Cole Porter: Kiss Me Kate; Silk Stockings (soundtracks).