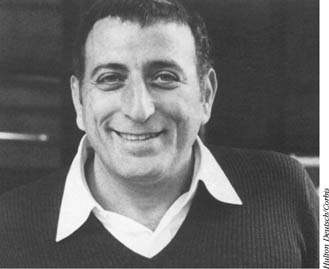

A balladeer, Tony Bennett used his big band and jazz training to forge a career as a popular music singer.

Icontemporary times, popular music embraces the songs of minstrel and vaudeville shows, dance music, ballads, musical comedy, music hall and all other kinds of music that you might expect to hear people whistling or humming in the street. Patriotic popular songs have seen many countries through depression, wars, and much of the economic, political, and social change of the past hundred years. But for the most part, popular music in the 20th century originated in the U.S., and has been about romance and good times, dominating the music industry from the advent of the phonograph and the radio, until the rise of rock’n’roll in the mid-1950s.

“Yankee Doodle” has been called America’s first popular song, and until the 20th century it was followed mainly by music of white, middle-class society. But there was another type of music that had been created in the Deep South, where African-influenced rhythms and vocal styles met with folk, “hillbilly,” and European classical forms and instrumentation. This juxtaposition of cultures and musical styles produced the heady and rhythmically complex sounds of the blues, jazz, ragtime, and spirituals, later known as gospel music.

The music of Africa was more rhythmically advanced than European music. Although their instruments were denied them in most places (a notable exception being “Congo Square” in New Orleans, Louisiana) the African rhythmic and melodic influence and genius could not be excised. These African musical characteristics found expression in work songs, field hollers, folk music, and the new hymns that were written to express the transplanted Africans’ new-found faith—spirituals.

In the 19th century, some African-Americans received training as musicians primarily so that they could entertain the plantation owner. Other African-Americans became church musicians or enlisted as bandsmen in the “coloured” units of the Union Army during the Civil War. Out of these plantation entertainments came the minstrel show and the cake walk.

Ragtime developed from the cakewalk, a slave dance that mimicked the stiff, European-derived dance postures displayed by white society at plantation balls. Later, it became both a part of the minstrel shows and a dance contest, in which the winning dancer or couple was awarded a cake. Musically, the cakewalk was performed by small groups playing banjos, fiddles, basses, and rhythmic instruments called “bones.” Cakewalk music was syncopated—it accented what would normally be the weak beats in the music. Ragtime appeared about 1890. “Rags,” as they were called, were originally pieces performed by individual pianists attempting to reproduce the sound of an entire cakewalk band. Later, ragtime compositions were transcribed for larger brass bands. After the Civil War, many unused military brass and percussion instruments found their way into pawn shops, or were simply left on the field. Some of these instruments were acquired by the former slaves, and were used to create community bands. Along with cakewalk and ragtime styles, the bands played a swinging, syncopated march music sometimes called “second line.” The combination of improvised second line brass music, ragtime, and the blues led to what is now called early or traditional Dixieland jazz. New Orleans and St. Louis, Missouri, were significant in the development and early popularity of ragtime. Two important ragtime composers were Scott JOPLIN and Jelly Roll MORTON.

Scott Joplin, famous for his compositions such as “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer,” wrote or co-wrote at least 40 ragtime pieces, and even a few rag operas. Jelly Roll Morton was a New Orleans pianist who played ragtime, and also claimed to have “invented” jazz. His style was unique, and there was some improvisation in his playing. Morton was also the first to note the importance of the Latin/Afro-Caribbean rhythmic influence in New Orleans music—he said “all good jazz has the ‘Spanish tinge.’”

In the late 19th century many popular songs were written for, and popularised by, a form of travelling entertainment known as the “minstrel show.” Minstrel shows employed African-American entertainers (or white musicians and singers made-up in “black face”) and featured many pre-jazz popular styles, including early blues, cakewalk music, and proto-ragtime songs, as well as folk music and popular songs. Songs from this era include “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” “Beautiful Dreamer,” “Oh Susanna,” and “Old Folks at Home.” Minstrel shows declined in popularity toward the end of the century, giving way to vaudeville and musical theatre.

Minstrel shows and vaudeville took the current popular songs around the country so that people could hear them. Very often the audience would then buy the sheet music and play the song on the piano at home, making their own entertainment. One of the most successful songs sold in sheet music was “After the Ball,” a popular waltz written and published by Charles K. Harris in 1892. Within a year, it was bringing in $25,000 a week; after 20 years, sheet music sales topped $10 million. The boom in sheet music sales spurred the creation of America’s first major music publishing centre on 28th Street in New York City, known as “Tin Pan Alley.”

Tin Pan Alley publishers employed staff songwriters and arrangers to produce a steady stream of popular songs. They launched the careers of some of America’s best-known, “golden age” songwriters and composers, including Irving BERLIN, George M. COHAN, George GERSHWIN, and Cole PORTER. Sensing the increased interest in popular music, Tin Pan Alley sought new ways to make sheet music more readily accessible to potential buyers. They moved it into department stores and the five-and-ten-cent stores. By 1900, the department store had become an important supplier of sheet music. At the same time, sheet music counters were placed in five-and-ten-cent stores.

The most aggressive marketing tool used by Tin Pan Alley, however, was the “song plugger.” These song pluggers were musicians sent out to the new store counters to sing and play current releases as an enticement to potential buyers. In addition, every music publisher sent song pluggers out to popularise their songs by singing them in restaurants and bars, and convincing popular entertainers to use them. Pianists were hired by music stores to play the printed sheet music so that customers could hear it. The song plugger became the “king” of Tin Pan Alley because of his influence over major stage performers and his gift of salesmanship. The pluggers promoted their songs at parades, picnics, political campaigns, circuses, on excursion boats, and even at baseball games.

A balladeer, Tony Bennett used his big band and jazz training to forge a career as a popular music singer.

In 1913, Billboard magazine began to publish a weekly count of the week’s top selling sheet-music. This was the first such chart in popular music. The initial listing consisted of 112 retailers. Within a few weeks, the list topped out at over 500 reports. Among the ten tunes on the first chart were “When I Lost You” and “Snooky Ookums,” both by Irving Berlin; “When It’s Apple Blossom Time in Normandy,” “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine,” and “That’s How I Need You.”

Between 1910 and the early 1920s, ragtime temporarily replaced the ballad as Tin Pan Alley’s most popular song form. Some of the popular Tin Pan Alley syncopated songs of that period included Joseph E. Howard’s “Hello, My Baby,” Bob Cole’s “Under the Bamboo Tree,” and the most famous of them all, Hughie Cannon’s “Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home.” The second most famous ragtime song of this period was Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” The tune is not really in ragtime at all, and syncopation is not a central feature. However, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” helped to make ragtime a national craze and established Berlin as a “king of ragtime.”

Thanks in large part to the strong rhythm of ragtime, social dancing spread through America and through the popular music industry. The syncopation of the rhythm was stimulating to the senses and the feet, and the new dances were easier to learn and perform than the formal dances of the previous generation. It was not long before “rag” dancing contests were featured in both ballrooms and vaudeville. Dancing schools began to open and thrive, and dance instructors became rich by giving private lessons. Vernon and Irene Castle were the greatest dancing stars of all. After starring in the musical The Sunshine Girl in 1913, in which they presented the turkey trot, they popularised one dance after another: the castle walk, the castle classic waltz, the castle house rag, and the castle tango. In the 1920s the influence of jazz brought in even more energetic dances—the Charleston, the shimmy, and the black bottom.

Another popular form of music that took Tin Pan Alley by storm during those years was the blues. It was brought to Tin Pan Alley in 1914 by W. C. Handy, bandleader and self-styled “father of the blues.” His “St. Louis Blues” was the first commercial blues to be published, and was the most widely performed and admired blues tune. It became an American classic and was featured by several stage stars including Sophie TUCKER. Recorded by military and dance bands, it also became popular abroad. Handy wrote other blues tunes, including “The Harlem Blues,” “The John Henry Blues,” and “East of St. Louis Blues,” but “St. Louis Blues” was his masterpiece. Most of the blues that were written for the commercial market came from Tin Pan Alley’s own songwriters, including Jerome KERN and George Gershwin, and they kept producing blues throughout the 1920s. For example, Kern wrote two blues pieces in 1920 and 1921, and Gershwin used blues harmonies and melodies in his symphonic works and in his folk opera Porgy and Bess.

World War I represented a virtual gold mine for Tin Pan Alley. The war in Europe had stimulated a renewal of patriotism and national pride, and when the United States entered the war in 1917, songs became an important part of the war propaganda. In no other American war were songs sung by so many people in so many different places. There was one song that seemed to capture the prevailing mood of wartime more than any other. This was George M. Cohan’s “Over There,” which became the classic tune of World War I. Twenty-five years after the famous song was written, George M. Cohan was presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Roosevelt.

After World War I, Tin Pan Alley moved from 28th Street to 42nd Street, but it remained a hit-making machine and the developing medium for talented new composers and lyricists. It also found new subject matter for its songs accompanying silent movies. In addition, the invention of the phonograph, radio, and the talking movies brought music to more people than ever before and was important in making songs popular.

The first records for the entertainment market were produced in 1894, and by 1924 thousands of phonographs had flooded the market. By the middle 1920s, nearly 130 million records were sold annually. This was a bountiful source of revenue for the Tin Pan Alley publishers, and a hit song began to be measured by the number of records rather than copies of sheet music sold.

Radio began to be marketed as a household utility after World War I. By 1929 there were 300 commercial stations to choose from, and within ten years the NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) and several national radio networks had sprung up. Broadcasts by the NBC and CBS radio networks featuring live and recorded music made overnight successes of many of the popular singing stars of the 1930s and 1940s, such as Rudy VALLÉE and Kate Smith.

One non-singing radio phenomenon was especially significant for American popular music. This was the disc jockey or DJ, who played his own selection of popular records on his radio programme, and became a very powerful factor in making hits.

The radio program Your Hit Parade was also a measure of popular song success during the early days of radio. This was a weekly Saturday night programme that lasted for 28 years. It presented the top tunes of the week based on the number of record and sheet music sales, and also on the number of performances the tunes got on radio, on jukeboxes, and in dance band performances.

In the 1930s dance music was the popular music of the time, and was played by the big bands or jazz orchestras. “Swing,” which was the most famous big band sound, is a style of playing that was popularised by groups such as the Duke ELLINGTON Orchestra, the Count BASIE Big Band, the Glenn MILLER Orchestra, and the various bands led by Benny GOODMAN. Swing remained virtually synonymous with America’s popular music until the end of the post-World War II era.

In addition to producing hit songs, some big bands also made stars out of their popular singers. These included Bing CROSBY, who was perhaps the most famous “crooner” of all, and the ANDREWS SISTERS, who were heavily featured on the radio as well as in a few films. Other notables were Ella FITZGERALD, who made her first hit single, “A Tisket, a Tasket,” in 1938, and Peggy LEE, who, in 1941, was hired as a replacement singer by Benny Goodman for his orchestra.

By the end of World War II and into the 1950s, popular music was dominated by romantic balladeers. These vocalists often had graduated from being big band singers, and they sang in a romantic, smooth, and understated style. Some of the most successful balladeers were Perry Como, Andy Williams, Tony BENNETT, Frankie LAINE, Nat King COLE, and Johnny Mathis, all of whom remained popular well into the 1960s.

No popular singer, however, matched the staying power of Frank SINATRA, whose popularity spanned six decades. After leaving the Tommy Dorsey group in 1942, Sinatra’s fame as a singer exploded. Hundreds of Sinatra fan clubs sprang up all over the country, and his records and concerts sold out. Sinatra was often mobbed by screaming women trying to tear off bits of his clothing when he appeared in public. In essence, Sinatra, a singer of popular music, was the first true “pop” star.

Starting in the late 1920s, musicals proved a prime source of popular music. Songwriters such as Irving Berlin, Richard RODGERS and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and Harold ARLEN wrote primarily for Broadway shows and Hollywood musicals, but their tunes became popular favourites. Many entertainers also emerged from the Great White Way and Hollywood during the 1920s and 1930s to become popular performers. One such performer was the dancer and singer Fred Astaire, who had several hits with his Broadway shows in the early 1920s and his Hollywood musicals starting in the early 1930s. Other popular singers to make their way to the silver screen included Judy GARLAND, Doris DAY, and Mario LANZA.

Disparate musical voices and styles, which include songs from the musical comedies of Broadway and Hollywood movies, new dance rhythms from ragtime, and the songs of Tin Pan Alley, together with the fusion of European and African traditions, combined to influence popular music. And this combination has given 20th-century popular music its extraordinary vitality and versatility.

In the mid-1950s, popular music as we know it today started to emerge from rock’n’roll, which marked the start of what we now call the rock era. A decade later, one of the most successful composers was Burt BACHARACH, who in collaboration with Hal David wrote more than 20 Top 40 hits for Dionne Warwick, beginning with “Don’t Make Me Over.” Bacharach also supplied hits for many other artists, including Herb ALPERT and the Carpenters. As a songwriter who maintains the romantic ideals of popular music, it is impressive that Bacharach has been able to find success in the cynical age of rock. His successful formula continues to reap rewards for many singers. Other popular composers and performers, such as Barry MANILOW, Barbra STREISAND, and composer Michel LEGRAND prove that popular music remains a formidable force.

Judi Gerber

SEE ALSO:

BLUES; JAZZ; RADIO; ROCK’N’ROLL; SWING; TIN PAN ALLEY.

FURTHER READING

Clarke, Donald. The Rise and Fall ofPopular Music (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995);

Hamm, Charles. Yesterdays: Popular Song in America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979);

Simon, George. The Big Bands (New York: Schirmer Books, 1981);

Stowe, David. Swing Changes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Count Basie: Count Basie; Irving Berlin: Irving Berlin Revisited; Tommy Dorsey: The Complete Tommy Dorsey; Duke Ellington: River Suite;

George Gershwin: Orchestral Music, Selections; Billie Holiday: Billie Holiday; Jerome Kern. Showboat;

Glenn Miller: Glenn Miller; Cole Porter: Kiss Me, Kate; Frank Sinatra: Songs for Swinging Lovers.

Daughter of Sissy Houston and cousin of Dionne Warwick, Whitney Houston (above) dominated the U.K. and U.S. charts with a series of huge hit singles between 1985 and 1990. With strong support from her record company, Arista, Houston released her eponymous first album in 1984. Featuring several No. Is, including “Saving All My Love for You,” “Greatest Love of All,” and “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me),” among others, it established Houston as a major force in American pop music.

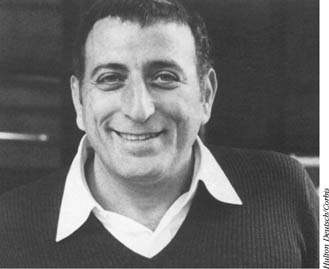

French composer, conductor, and educator Nadia Boulanger (left) is best remembered for her energy and influence as a teacher at the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau near Paris. A friend of Stravinsky, she used his music and that of Fauré to set the standards for her pupils. She was also renowned for her work as a conductor and champion of French Baroque and Renaissance music.

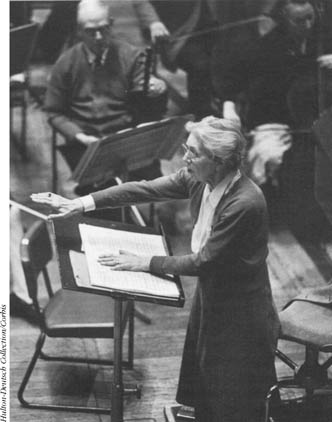

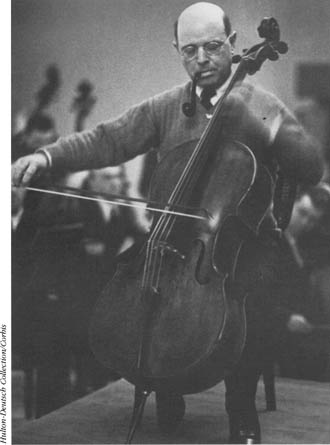

Catalan cellist Pablo Casals (left) plays the Dvorak Cello Concerto in Prague in 1937. In 1936, under the threat of execution by Franco, he moved over the border from Spain to France. He played abroad many times during the next few years, but withdrew from public life in 1945 when he realised that political moves would not be taken against the Spanish regime. He did not play again until 1950.

Their name taken from a novel by Herman Hesse, Steppenwolf (below) released their first album in 1968. It featured the song “Born to Be Wild,” which was used in the opening sequence of the film Easy Rider. Both song and film are now cult classics. Although singer John Kay has tried to revive the band’s fortunes since then, subsequent releases have not been able to recapture former glories.

Duke Ellington (above, at the piano) and his orchestra in a scene from the Columbia Pictures film Reveille with Beverly (1945). The 1940s were fertile years for Ellington, during which he worked closely with co-arranger Billy Strayhorn and the rest of the tightly knit Ellington organisation.

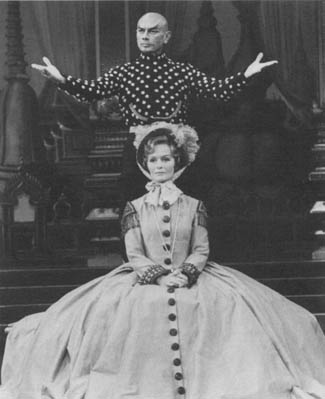

Yul Brynner and Virginia McKenna (right) perform in the musical The King and I in a revival in London in 1979. Though Brynner is forever associated with the show as the domineering King, it was originally written, in 1951, as a vehicle for the actress Gertrude Lawrence to feature as Anna— the show’s starring role.

Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (left) rehearses for a performance at London ’s Royal Festival Hall in 1959. Gould only took to the international stage in 1957, when he toured the Soviet Union, Europe, and Israel with the Berlin Philharmonic and conductor Herbert von Karajan to widespread acclaim. However, he retired from live performances in 1964 to concentrate on recording, believing the concert hall to be obsolete.

Stan Getz (below, right) performing with Lionel Hampton at a jazz festival in New York in 1982. Getz, one of the most highly regarded tenor sax players in jazz history, is also remembered for recording “The Girl from Ipanema” with Astrud Gilberto, which was his biggest hit.