CHAPTER 3

HEROIC FOUNDATIONS

Chicano/a Heroes in Family, Farmwork, and War

I was here before the Chicanos were even invented or came about.

Stan Padilla,

interview, July 12, 2004

My mother was always telling me, “Son, get a job in the shade. Just get a job in the shade.”

Ricardo Favela,

interview, July 20, 2004

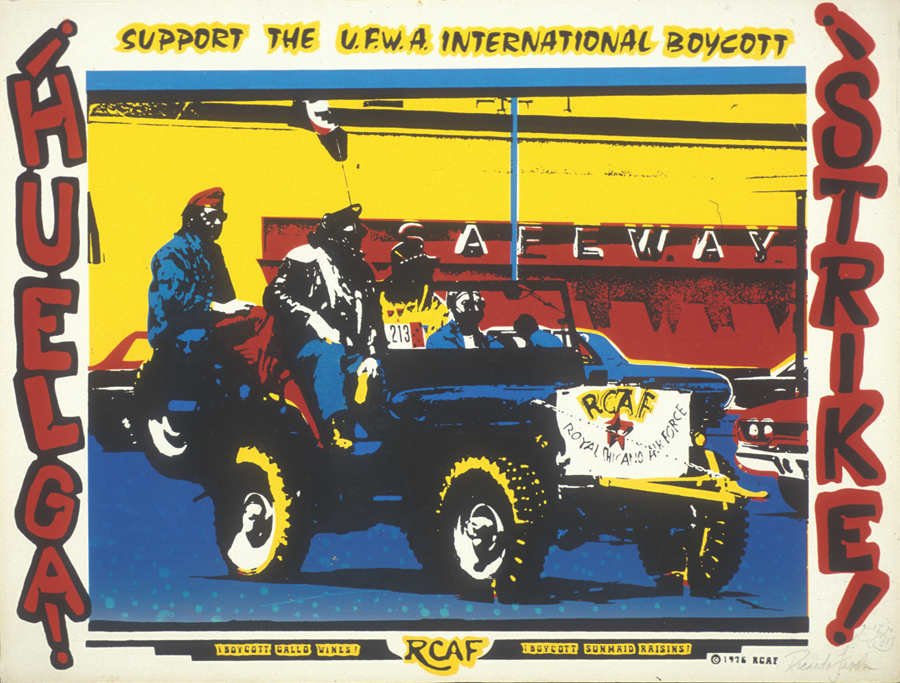

In 1987, Ricardo Favela created Aquí Estamos . . . Y No Nos Vamos!!!, a poster that uses a rallying call as part of the image and title. A popular slogan of the Chicano movement, the phrase relies on a Spanish rhyme scheme to convey an abridged message to the political status quo from Chicanos/as on the front lines of the farmworkers’ strike, university campuses, and the streets of their neighborhoods (see plate 12).1 Repurposing a political slogan to encapsulate Royal Chicano Air Force history, Favela conveys how the Chicano/a art collective fashioned “a poetics never separate from politics” (Limón 1992, 86). The rallying call summarizes the political platforms of the Chicano movement and the Chicano/a desire for a sense of native belonging in the United States. In 1987, the catchphrase also pertained to the RCAF’s documentation of their history in the absence of institutional recognition.

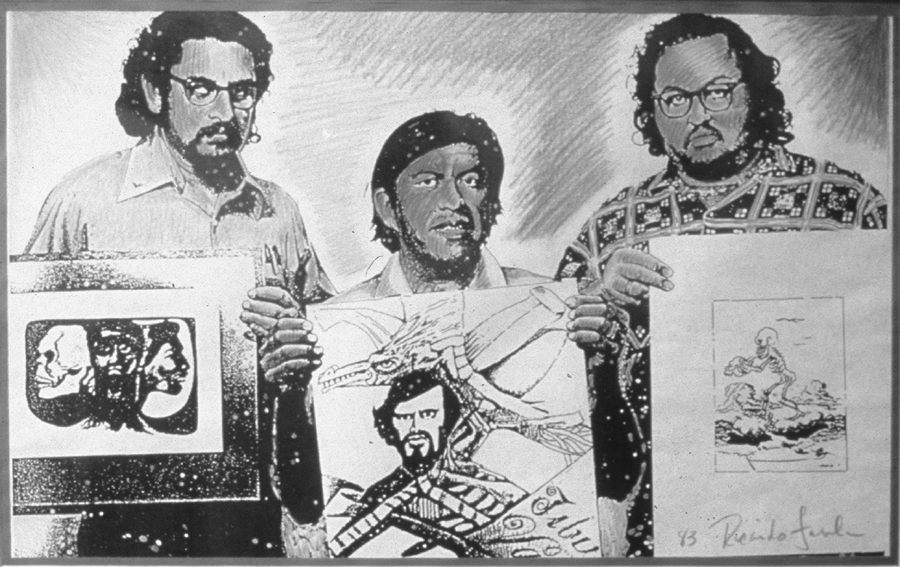

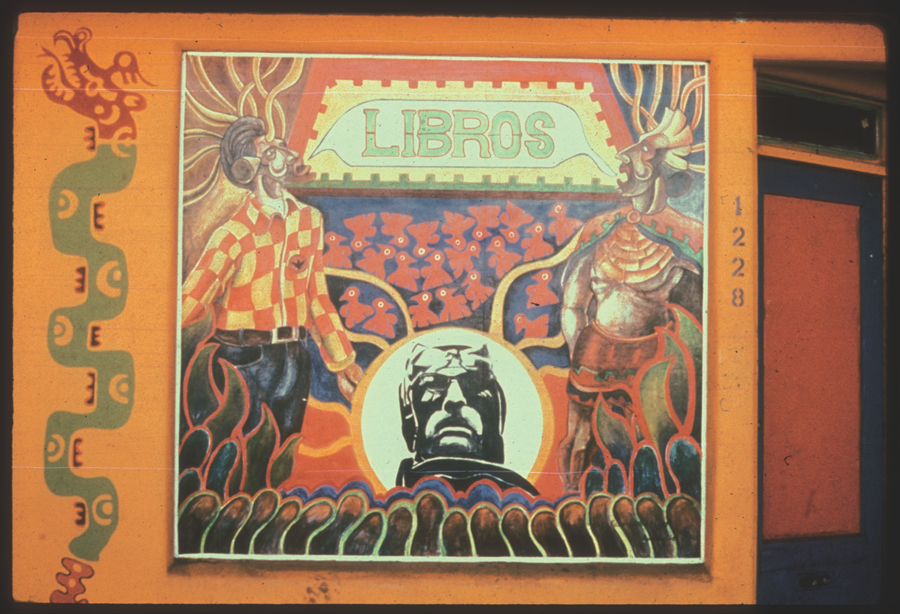

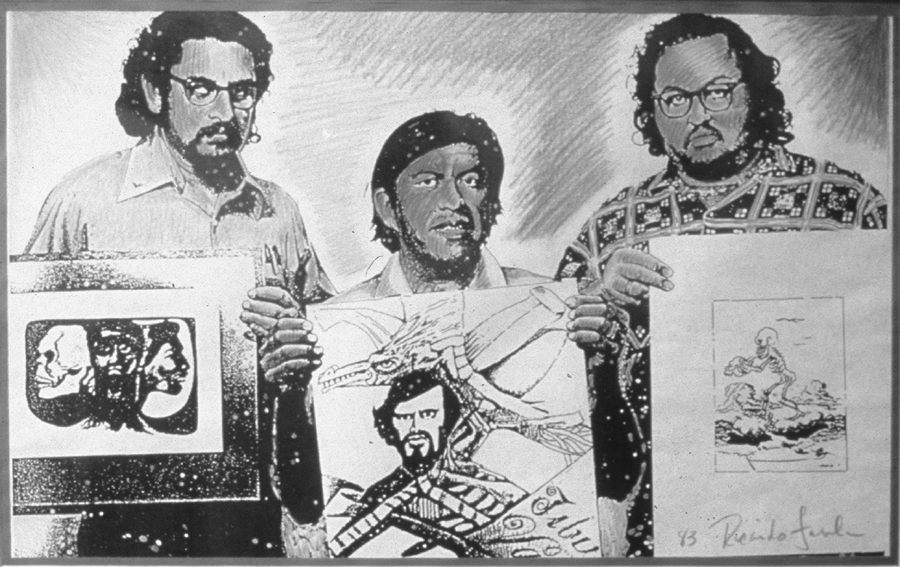

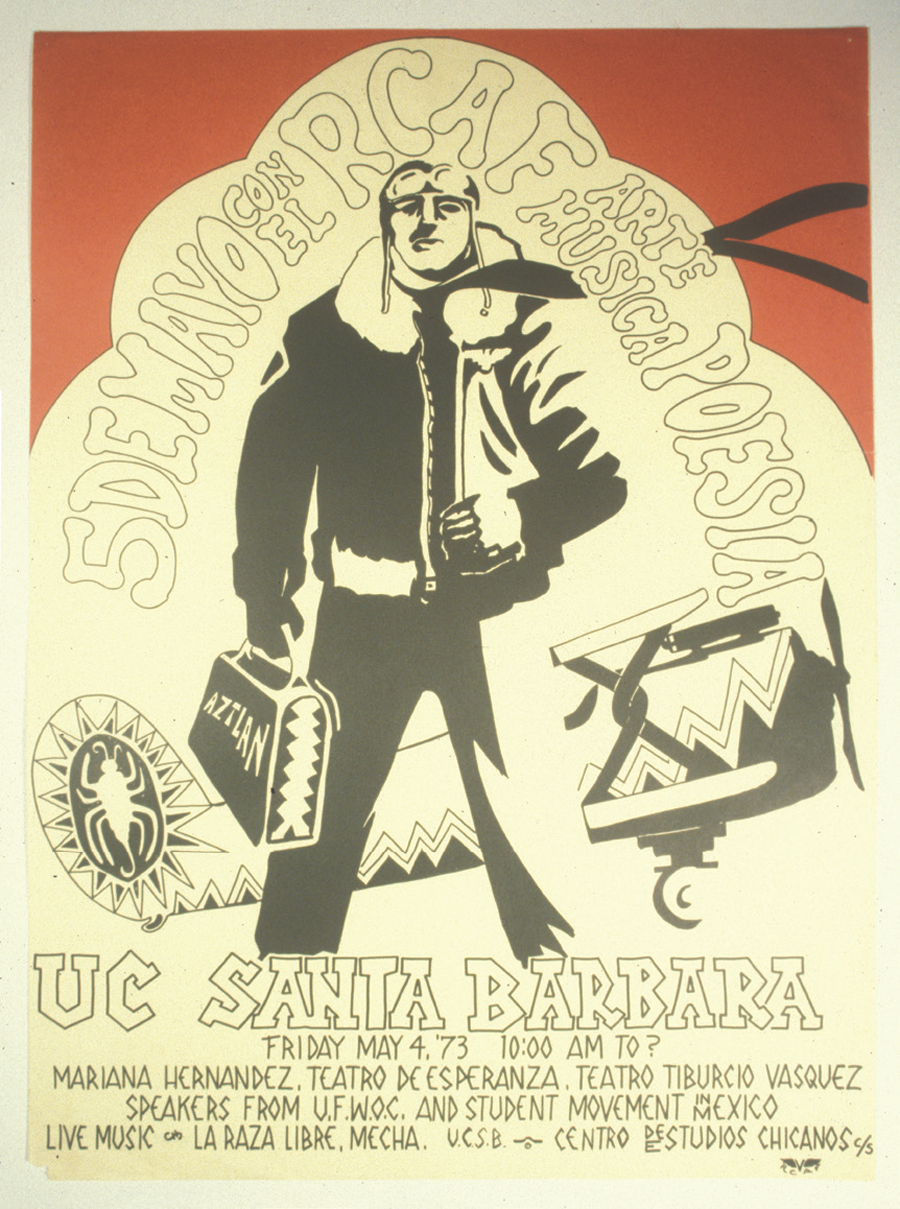

Figure 3.1. Ricardo Favela, Compañeros Artistas (1983). Canon 400 copy machine and color pencil. Royal Chicano Air Force Archives. The California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives. Special Collections Department, the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

The large size of the slogan prompts viewers to simultaneously experience the aesthetics of the poster’s message (Romo 2001, 2011), or to see, read, and hear the slogan as they contemplate the image and secondary title at the bottom of the poster: “We’re still here . . . 18 years later.” The secondary title signals a personal memory within the visual field that is supported by the fact that Favela created the poster based on a photograph, which he photocopied and embellished with color pencil (see fig. 3.1).2 From the work’s photographic origins to his use of color in the screenprinting process, Favela questions spatial construction—both the formal space of the poster and the figurative space of memory.

The tilted rectangle that frames the artists, for example, highlights the artwork’s construction. Favela’s decision to render the RCAF artists in black and white adds formal contrast to the orange-to-yellow gradation behind the men. Within the slanted frame of the picture that surrounds the artists, the acronym “RCAF” repeats in blue sequential lines that correspond with the poster’s background. But the slanted frame pierces the poster’s outer border with two of its four points, reinforcing the idea of space as a figurative, personal, and aesthetic experience.

Of particular importance to this chapter is the portrait of the artists, each of whom holds artwork that tells stories about Chicano/a heroes. Esteban Villa holds a portrait of Tiburcio Vásquez, a nineteenth-century Californio outlaw who championed Mexican American rights after California’s annexation in 1848. A clenched fist with shackles rises from the left corner of the image, suggesting sustained Chicano/a resistance through the combination of a hero and a heroic symbol. On Villa’s left, Ricardo Favela holds an image of a skeleton that gestures to José Guadalupe Posada, the Mexican illustrator who created a visual lexicon of revolutionary images that critiqued ruling power in Mexico during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. On Villa’s right, José Montoya holds a piece that also incorporates a skull, but as part of a tripartite head, a prominent symbol in Chicano/a art that represents the racial and cultural mixtures of Chicano/a ancestry (Arrizón 2000, 27). Montoya’s image is a serigraph titled La Resurrección de los Pecados (1971), which he produced with his RCAF colleague Armando Cid.3 Along with the skull, the tripartite head includes an indigenous man in profile and a central man whose enlarged eyes and open mouth suggest an audible howl, alluding to the horrors of war—both the colonial legacies and contemporary destructions.

Aquí Estamos . . . Y No Nos Vamos!!! contains pictures within pictures of Chicano heroes and heroic allegories that simultaneously foster a Chicano/a sense of place in the nation while resisting the limitations of geopolitical borders. Holding artworks that include heroes and heroic allegories from multiple spaces and times, the three Chicano artists stand together above the secondary textual line. The layers of historical representation commemorate the RCAF’s founding and its role in creating and disseminating a Chicano/a verbal-visual architecture that fortified the Chicano movement.

Using heroes and heroic allegories as a mode of analysis for RCAF art history is perhaps unexpected in the twenty-first century. The trope of the hero is largely critiqued in Chicano/a studies scholarship for its replication of the patriarchal values of the Chicano movement, which elided Chicana agency by privileging hypermasculine imagery and heteronormative representations of the Chicano/a family (E. Pérez 1999). “Never defined in neutral terms,” the symbol of “la familia,” Richard T. Rodríguez writes (2009, 20), reanimated images of heroism “in the name of egalitarianism,” redressing the emasculation of social inequality through a visual lexicon entrenched in hetero-patriarchy. As Ricardo Favela’s poster demonstrates, the RCAF appropriated leader emulation from the nation-building strategies implicit in US history to combat the absence or stereotypes of Chicanos/as in mainstream media and popular culture. In repurposing dominant modes of representation, Chicano/a artists reproduced similar forms of exclusion.

Reflecting on machismo in the Chicano movement and the “clear masculine trope [that] ran though the language of Chicano Power,” Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar (2006, 274) notes the parallel with the language of Black Power; but “the movement was not monolithic,” he contends, a point he supports in an interview with Elaine Brown, chairwoman of the Black Panther Party in the 1970s. Ogbar asks her about the Black Panther Party’s public image, or the verbal and visual lexicon that “clearly lionized black men” (276). Brown responds with a question: “Did these brothers drop from ‘revolutionary heaven’? Of course not. We were working through issues” (276). I tend to agree with Brown in regard to the Chicano movement, but not to dismiss the real exclusions of women and queer Chicanos/as. Rather, I agree with Brown because doing so accounts for the historical reality and patriarchal structures under which Chicanos/as, African Americans, and other disenfranchised people advanced movements in the 1960s and 1970s for self-determination and mental decolonization.

Heroization is necessary in a foundational analysis of the Royal Chicano Air Force. It allows for close readings of art made by a vanguard collective that was articulating and performing into being a self and group identity adapted from several cultures and civilizations that constructed the history of the Western Hemisphere. Thus, the idea of Chicano/a heroes should not be so easily dismissed in the twenty-first century for its exclusionary outcomes. Instead, it should be positioned as part of the trajectory of decolonial thought in which scholars continue to rephrase ideas from 1960s and 1970s Chicano/a art in academic terms. Theoretical lenses that emerged in the 1990s, for example, took shape in the visual vocabulary of decolonization that developed during the US civil rights era.

1960s and 1970s consciousness-raising produced racial, ethnic, political, and cultural awareness largely through heroization, which not only spurred subsequent theoretical paradigms but generated some of the very words used to express them. There are clear connections between RCAF art and academic paradigms like Emma Pérez’s (1999) decolonial imaginary. I wonder if a decolonial imaginary, and for that matter, an “alter-Native” lens for Chicano/a art (Gaspar de Alba 1998) or a “remapping of American cultural studies” (Saldívar 1997), would have been possible without the RCAF’s artwork and other Chicano/a art produced during the Chicano movement. I concretize my point from the beginning of this chapter with an analysis of heroes in Antonio Bernal’s 1968 murals, painted at El Teatro Campesino’s original headquarters in Del Rey, California. Alongside Bernal, the RCAF laid foundations for decolonial ideas in their visualizations of Chicano/a history.

Using oral history as an archival tool, I enhance the experience of looking at RCAF art by contextualizing their verbal and visual claims of Chicano/a nativity in the United States before, during, and after the Chicano movement. This is an important context for thinking about RCAF art that heroizes Chicano/a farmworkers and aligns the farmworking experience with third world consciousness. Whether or not RCAF members migrated to the United States with their families due to the sociopolitical upheaval of the 1910 Mexican Revolution or as part of the labor force of the 1942 to 1964 Bracero Program, RCAF members do not determine their indigeneity through geopolitical borders, a point they make continually in their artwork.

In building a Chicano/a sense of place in the United States, the RCAF remapped colonial understandings of the world.4 They did so by exalting the ordinary, or heroizing the Chicano/a experience of family, farmwork, and war to address cultural loss through migrations that were (and are always) tied to larger sociopolitical and economic forces. None of these ideas were executed perfectly in the 1960s and 1970s, since the RCAF did not fall from revolutionary heaven; but the RCAF was part of a decolonial vision of the future and dealt directly with issues that people of color continue to face.

Perceiving their ancestry in real and symbolic ways, RCAF members focused on the roles of their mothers in interviews, describing them as teachers, workers, and guardians. In recalling her mother, Irma Lerma Barbosa revealed a female-centered Chicana consciousness-raising prior to the Chicano movement, suggesting that, as numerous Chicana scholars have since argued, Chicana self-actualization began before the 1960s and 1970s. Collaborating with her colleague Kathryn García on a flyer to announce the Conferencia Femenil, Lerma Barbosa planned a meeting that politicized the mother-child relationship beyond the domestic sphere and in relation to third world consciousness through the recovery of indigenous knowledge. Likewise, José Montoya’s “La Jefita” (1969) is a canonical poem that foregrounds the farmworking mother’s place in defending the rights of the Chicano/a family. The poem has been critiqued for its idolization and not humanization of the farmworking mother, but I revisit the poem for its attention to sound as a heroic allegory. Among these works, I read several RCAF creations for their use of heroic tropes and allegories that fused the aesthetic with the political and the instrumental.

The “forgotten heroes and heroines of the frontier”5

The re-creation of heroes and heroic allegories in Chicano/a history began, according to Emma Pérez (1999, 8), when Chicano historians “constructed a distinct knowledge of Chicano history in the twentieth century, a knowledge that manifests four periods and four dominant modes of thinking.”6 From sixteenth-century conquest, nineteenth-century war, and the US annexation of Mexican territories, to the 1910 Mexican Revolution and the 1942 to 1964 Bracero Program, Chicano historians arrived at the Chicano movement as the next great event in their people’s history. They advanced a conceptual frame for historical actors who resisted US annexation and aligned with the populist side of the Mexican Revolution. In doing so, Pérez asserts, Chicano historians produced the trope of the Chicano hero and, indirectly, the heroic intellectual (1999, 8–9).7 With the Bracero Program, Chicano historians argued that Chicanos/as were (and are) a colonized workforce (8). Following interpretations of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century events, Pérez tracks the development of the scholarly perspective that Chicanos are “social beings, not only workers” and, finally, that “Chicanos are also women” (8). Each of these modes of analysis is problematic for Pérez because each responds to colonial moments like war, annexation, and binational treaties (8).

For my purposes, Pérez’s critique of the Chicano hero and its allegories is important to RCAF history because both emerged representationally during the 1960s and 1970s and were central to Chicano/a artistic production. Heroism also persists as an important motif beyond the initial decades of the Chicano movement, evidenced by Ricardo Favela’s poster Aquí Estamos . . . Y No Nos Vamos!!! (1987), in which he restages a photograph of RCAF artists holding artwork that they created in the 1970s, presenting nineteenth- and twentieth-century heroes alongside pre-Columbian symbols.

The point of my discursion into Pérez’s critique of the colonial moments upon which Chicano/a history is based is that while leader emulation is problematic, heroes and heroic allegories are nevertheless complex, theoretical interventions on regional hegemony.8 Heroes in Chicano/a art emerged as pathways to a self-determined Chicano/a identity, served as visual shorthand for intellectual and political treatises, and simultaneously exalted an alternative trajectory for Chicano/a historical consciousness while signaling its fragmentation. In 1968, for example, Antonio Bernal painted two murals on the facade of El Teatro Campesino’s location in Del Rey, California, using historical figures and symbolic composites to represent each of the great events to which Pérez refers. One mural featured a line of pre-Columbian figures headed by an indigenous woman (S. Goldman 1990, 167). Bernal replicated the form of the Maya murals in Room One at Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico, by depicting his figures in flat, horizontal lines (167). Holly Barnet-Sanchez (2012, 247) claims that by employing both the form and content of the pre-Columbian frescoes, Bernal testified to “the relevance of ancient beliefs and practices for Chicano/as as philosophical and theoretical underpinnings” of the Chicano movement and, specifically, in homage to El Teatro Campesino performances.

Bernal’s murals put forward an intellectual trajectory for Chicano/a history—from an indigenous past to a political present, the latter conveyed by the line of figures on the wall opposite from the indigenous procession. There, Bernal painted nineteenth- and twentieth-century heroes led by a soldadera, a female soldier from the 1910 Mexican Revolution. While she is unidentifiable, the heroes that follow, all of whom are male, can be identified. From Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, Bernal’s line moves to Joaquín Murrieta, César Chávez, and Reies López Tijerina, as well as a Black Panther resembling Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., two figures that signal the multiracial environment of the Chicano movement. These figures are also arranged in a single line, suggesting that Bernal desired aesthetic uniformity between the pre-Columbian murals he referenced and the contemporary figures he rendered (S. Goldman 1990, 167). For Carlos Jackson (2009, 77), the consistency between the two murals communicates a sense of “historical progression” or evolution of civil rights in the United States.

But Bernal’s aesthetic organization can be interpreted in ways other than progress toward a more democratic society (Jackson 2009, 77). The figures in both murals were appropriate for El Teatro Campesino’s headquarters because their arrangement reflects a roll call of theatrical archetypes. The murals visualized a cast of characters performed by Chicano/a actors who invented a theatrical genre for Chicano/a farmworkers (Valdez 1966, 1967; Huerta 1973, 1989). The anonymous pre-Columbian woman and la soldadera in Bernal’s murals support this reading, since Chicana actors and female roles were limited to these types in early El Teatro Campesino performances (Broyles-González 1994).

The murals also mirrored the range of Chicano/a cultural production in the late 1960s, particularly the proliferation of Chicano/a poetry. Bernal’s lines of Chicano/a heroes paid homage to Rodolfo Gonzáles’s long poem “Yo Soy Joaquín” (1967). As Gonzáles moves his hero Joaquín through the poem, he crosses several regions and epochs of pre-Columbian, Mexican, Californio/a, and Chicano/a history, circling back to previous periods and making the past present in his epic verse (Barnet-Sanchez 2012, 248). Likewise, Bernal’s murals were metaphysical inquiries into Chicano/a historical consciousness; they collapsed space and time through representative figures in order to trace historical antecedents of the Chicano movement. From the verbal to the visual, the poem and the murals made intellectual claims through pre-Columbian imagery as well as subsequent historical figures to inspire Chicano/a audiences.

The poetic elements of Bernal’s murals directly engaged the intentions of the space in which they were painted. A mural showcasing a procession of past and present figures was readable imagery for El Teatro Campesino audiences. Many people who frequented the group’s headquarters participated in the 1966 United Farm Workers march from Delano, California, to Sacramento (Barnet-Sanchez 2012, 248). Luis Valdez described the farmworkers’ march as its own “theatre about the revolution,” a point that underscores the transition of a political audience into spectators of cultural affirmation on El Teatro Campesino’s stage in Del Rey (Barnet-Sanchez 2012, 248–249). On the most basic level, Bernal’s procession of heroes beckons Chicano/a viewers into the center, or cues them to fall into line to watch El Teatro Campesino pull “the past into the present,” Holly Barnet-Sanchez writes, as “legendary individuals gather” on the exterior walls “to envision their collective future” (251).

More than a historical progression, Bernal’s murals suggest a circulation of ideas that exalted pre-Columbian civilization as an allegory for Chicano/a origins alongside the rise of populist mobilizations that led to the 1910 Mexican Revolution and their perceived reincarnations in the Chicano movement. But Bernal’s murals also replicated the structure of nationalist mythos, or the historical ordering of epochs contingent on patriarchal understandings of war, annexation, and sociopolitical uprising. In regard to Bernal’s symbolic representation of female heroes, Guisela Latorre (2005, 100) claims that the generalities of female archetypes in Chicano/a cultural production personified “the anxieties generated by the active participation of women in critical historical events.” One wonders why the likeness of Dolores Huerta (or Angela Davis, for that matter) was not considered by Bernal for murals that identified local, regional, and national leaders of revolutionary and civil rights movements through portraiture.

Yet, despite the limitations of Bernal’s female symbols, he visualized a political history for the Chicano movement that parallels the theorizations of scholars in the 1990s who identified actual female soldiers fighting on the front lines of the Mexican Revolution or working within the system for political reform.9 Claiming that soldaderas “have marched through most of Mexican history,” Elizabeth Salas (1990, 120; emphasis mine) proposes female combatants and caretakers of the wounded as precursors to Chicana activists, irrespective of geopolitical borders. Vicki Ruiz (2007, 171) underscores Salas’s historical connection as a figurative one between “Mesoamerican women warriors (the ancestors)” and “las soldaderas and their symbolic descendants—Chicana student activists.” Bernal’s murals also gestured to Emma Pérez’s idea of the decolonial imaginary in which she writes Chicanas into history by claiming them as political descendants of Mexican feminists working within and against the patriarchal order of government and political discourse in the early twentieth century.10

Bernal’s murals resonate with Pérez’s desire for Chicana history that is not only decolonized but decolonizing—a tool that can be activated by a third space, where “third space agency is articulated” (E. Pérez 1999, 5).11 An area in between dominant paradigms where “subjugated histories” are “written as something new coming into being,” the decolonial imaginary is a space “in between that which is colonialist and that which is colonized” (E. Pérez 1999, 4, 7). Subsequently, it is often contested space because it can “replicate, copy, and duplicate first world methods and tools,” if not interrogated in its expression of alternative history, knowledge, and culture (4). Attempting to make Chicano/a consciousness visible on the walls of El Teatro Campesino’s building, Antonio Bernal created a decolonial imaginary, despite the incompleteness of his vision.

When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are: The Heroic pre-Columbian Past

The Royal Chicano Air Force imagined a decolonial Chicano/a history in the 1970s through murals created in Sacramento’s Chicano/a neighborhoods. Between 1975 and 1976, RCAF artists Luis González, Ricardo Favela, and Esteban Villa painted When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are, a striking mural with a provocative title, in the farmworker program dining hall of the Sacramento Concilio, Inc. A vital membership association for all Chicano/a organizations, the Concilio acquired and distributed funds for programs like Breakfast for Niños, a service that provided schoolchildren with morning meals (Ricardo Favela, interview, July 20, 2004). It also assisted La Raza Drug Effort, a prevention program that served the local community (“Special Board Meeting” 1974). Housing a dining room for farmworkers, the Concilio offered space to multiple groups in the Chicano/a community to practice various modes of citizenship—from discussing and voting on United Farm Worker measures and participating in workshops and administrative meetings, to eating together in a room where RCAF artists painted a mural that positioned the Spanish conquest of Mexico as a major event in the history of the Western Hemisphere.

When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are also gestured to a pre-Columbian framework for Chicano/a art by fusing several important sites of Mesoamerican civilization.12 The mural included the pyramid El Castillo from Chichén Itzá, a rendering of the god Tlaloc—with altered features that suggest a pastiche of multiple deities—and several representations of the Mexican Inquisition, an extension of the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth centuries (Corteguera 2012).

On the left side of the mural, a large skeleton holds a wooden cross in his upraised arm as if ready to strike; his accusatory posture mirrors that of another skeleton holding a blazing torch in front of a wooden door with flames shooting from the door’s barred window.13 In the background, El Castillo sits vacant and unused as an eagle warrior in the mural’s bottom left corner looks directly at the scene, bearing witness to the calamity. An indigenous man sits above the fiery scene and a wall of bones that represents the tzompantli, or skull rack, inside the Aztec pyramid, the Templo Mayor. Sitting on top of a grassy hill, the indigenous man raises his head and hands toward the sky. The scene evokes the Hill of Tepeyac, where the apparition of the Virgen de Guadalupe in 1531 led to the erection of her shrine on the former site of worship for the female deity Tonantzin. In the RCAF’s visualization of the conquest, the artists portray the immediacy of the violence and a lingering anxiety over spiritual loss in their contemporary moment.

The assemblage of indigenous symbols, places, and deities also suggests feelings of frustration over a lack of knowledge. The frustration resonates in the mural’s title, When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are, which anticipates a secondary clause, or a conclusion to the sentence of what one should tell his or her mother. If the mural’s collage of pre-Columbian images is the next clause (what one tells his or her mother), the assortment of signs and symbols conveys fragmentation and an uncertain pride in one’s ancestry. For Chicanos/as in the midst of politicization, armed with a growing sense of self-awareness but faced with a lack of access to information, the mural and its title express an emotional experience of spiritual and cultural loss.

Other imagery incorporated into the mural supports the theme of loss because it presents symbols of colonization, an important legacy within the Chicano/a worldview. In the center panel, the artists painted a sacred heart of Jesus with the Eucharist adorning its center. The heart is encased in a larger circle on the back of an animal that is also enclosed in a circle.14 The image denotes Aztec heart sacrifice, but its anatomical likeness aligns it with Catholicism, fitting the scene’s turbulent depiction of religious conquest.

Directly above the sacred heart of Jesus, the artists painted a large female figure with a United Farm Workers huelga bird covering her lower body. She is framed by red sun rays similar to those that appear behind the quintessential portrait of La Virgen de Guadalupe. Her white coloring denotes an otherworldly presence. In both size and color, she reflects Mujer Cósmica (1975), the mural that Esteban Villa created at Chicano Park in San Diego. As the mother figure of this mural, she stands before the troubling scene, and below her a poem written by Luis González is transcribed. The poem, also titled “When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are,” reads,

Cry on your pyramids memories

Tu corazón no se recuerda,

tu corazón no se recuerda,

the sun is still your father

planting maiz for Moctezuma

The land is still your mother

eso nunca olvidarás,

eso nunca olvidarás,

giving birth to magic children

eso nunca olvidarás c/s15

The verse is a lamentation, using a chorus that speaks directly to its audience in the farmworkers’ dining hall. While the poem conveys the contemporary Chicano/a community’s historical loss of ancestral memories—an absence painfully felt in the heart—Luis González’s lines “the sun is still your father / planting maiz for Moctezuma / The land is still your mother” suggest that a physical connection between the Chicano/a farmworker and the land remains unbroken. González frames the connection around labor, politicizing it for Chicano/a farmworkers who harvest California’s agricultural fields not for Moctezuma but under a different ruler. The farmworker that González hails and interpolates in the poem through possessive pronouns is the mural’s protagonist or hero, traveling through an odyssey of cultural, spiritual, and ideological clashes between civilizations, reflected in the mural’s assortment of symbols, locations, and creation stories.

The indigenous imagery in When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are, as well as the historical disconnect it simultaneously conveys through a mishmash of symbols, was endemic to early Chicano/a art. The RCAF artists reached back into histories beyond the United States, probing sources like Mexican calendars for an iconography with which they could historically, culturally, and spiritually connect. “We took a step consciously in the seventies,” RCAF artist Juanishi Orosco explains, “to project . . . the true values that we have in our community. You wouldn’t see them anywhere. You wouldn’t go to a gallery and see that. You wouldn’t go to a store and see that. Unless you went to a Mexicano restaurant or something like that and [saw] a calendar. But other than that, where would you see it?” (Juanishi Orosco, interview, December 23, 2000). Orosco refers to a common practice amongst Mexican American businesses in the twentieth century of giving annual calendars to their patrons, a practice that subsequently introduced Chicano/a artists “to a wealth of images illustrating Mexico’s indigenous heritage, cultural traditions, and regional diversity” (Romo 2001, 102–103). “For many people,” Terezita Romo writes, “these prints became ‘art works’ after the calendar dates were cut off and the image was framed” (102–103).

In his interpretation of Gilbert “Magú” Luján’s calendar piece Hermanos, Stop Gang War (1977), Rafael Pérez-Torres (2006, 137) asserts that the calendar was an aesthetic blueprint for Chicano/a art, becoming “a means to engender belonging, to identify a neighborhood as a community.” Calendars were an accessible means by which to iconicize and disseminate empowering images of indigeneity and cultural histories, which Romo (2001, 103) claims “provided some of the most memorable icons in Chicano art.” The calendar’s form, or how it was made, also deeply influenced Chicano/a art practices. Unlike the Mexican versions, Chicano/a calendars emerged from a collaborative process in which multiple artists participated in their production (Romo 2001, 103; Jackson 2009, 73).

The RCAF’s appropriation of pre-Columbian imagery from calendars was an act of “recovery and recuperation of Chicano/a and Mexican history,” Guisela Latorre (2008, 18–19) writes, adding that while such history “predated the encroachment of Spanish colonialism and Anglo-American expansionism,” it was “denied to most of these activists in the US public school system.” Esteban Villa’s reflections on early appropriations of precolonial imagery support Latorre’s claim. “In the beginning,” Villa confessed, “I didn’t know what I was doing [when] I would use, for example, some of these Mayan, little deities.” Mining images from “anthropology books,” Villa recalled that he was once asked if he was the artist who had made a “Mayan drawing there at the restaurant.” When he replied that he had, he was told, “I don’t think that’s for food; that’s when they sacrificed people and had them for dinner. Cannibalism. When they ate the heart and stuff. You don’t want that in a restaurant. . . . Don’t paint that anymore.” Villa’s anecdote conveys the Chicano/a desire for a culturally relevant history in the 1960s and 1970s, one that he tried to access on his own but “was all incorrect,” he explained, adding that “I was really trying. I just wanted anything to make a connection . . . because I was coming already from European [art]: French Impressionism, German Expressionism, Dutch Realism, Italian Renaissance. . . . And when I landed here in Sacra . . . I wanted my own influence” (Esteban Villa, interview, June 23, 2004). Villa’s desire for his own artistic influence was an attempt to decolonize his otherness from the Eurocentric cultural vision of the Western Hemisphere, or to embody the pre-Columbian knowledge that had become disembodied for Chicanos/as through successions of colonization and the reordering of their historical place, or a lack thereof, in the master narratives of two nations (E. Pérez 1999, 6).

Villa’s mention of “cannibalism,” for example, alludes to Western misperceptions of anthropophagy in Mesoamerican societies—a legacy of cultural imperialism to which Spanish colonialism and US expansionism gave rise. Villa used the humorous anecdote to contextualize the systematic denial of pre-Columbian histories for Chicanos/as. He had, after all, been denied information about indigenous cultures and histories in his education and, as he states specifically, in his training at the California College of the Arts. Villa’s visual choices were declarations of “indigenous identity as an identifying marker of the Chicano/a experience in this country,” Latorre (2008, 4) writes, adding that these “indigenist images and ideas” did not necessarily “come directly from their own personal indigenous experiences.” Rather, they were part of a politicization process “that prompted them to study Mexican history and culture” (4). Esteban Villa, Ricardo Favela, and Luis González’s effort to reconnect with pre-Columbian cultures in When Your Mother Asks You Who You Are was part of a larger phenomenon in which Chicano/a artists reconfigured pre-Columbian and Mexican motifs within a Chicano/a context in order to forge a sense of place in the United States that attended to their local, national, and global positionalities (Noriega 2012, 4).

When Your Mother Asks Who You Are poses a self-reflexive question to viewers. After viewers take in the violent scene, the title, written directly below the mother figure and above the poem, provokes a sense of loss and a desire for missing knowledge, ideas that are reinforced by Luis González’s verse. But the mural also positions the mother figure, symbolic of previous generations, as heroic. The mother figure in the mural extends her arms and opens her hands to viewers, communicating that Chicano/a identity is a history accessed genealogically.

The Heroic Chicano/a Family

The 1960s and 1970s Chicano/a generation signaled an ideological shift from the previous generation of Mexican Americans, announced by a self-chosen designation, but the shift did not discount family histories of migration, hard work, and sacrifice.16 Rather, Chicano/a artists, and the RCAF in particular, heroized their Mexican and Mexican American families to make their lives and contributions in the United States visible. While a historical analysis of the Bracero Program is beyond the scope of this chapter and book, its absence from the “Great Events of US History” exemplifies the exclusion of Mexican and Mexican American contributions to the nation (E. Pérez 1999, 132n26). It also reflects contemporary discourse on US immigration policies that do not consider lessons learned from this enormous labor program.

For my purposes, the centrality of the railroad during the Bracero Program, and in moving Mexicans and Mexican Americans across the US Southwest, is an important symbol in RCAF artwork and one with which they frame their family stories.17 RCAF artist Rudy Cuellar testifies to the railroad’s importance in the Chicano/a origin story in his poster Agosto 7 (1977). Recalling the importance of calendars in the formation of Chicano/a art practices, Agosto 7 was part of the RCAF’s calendar History of California (1977), produced by San Francisco’s Galería de la Raza and the RCAF’s Centro de Artistas Chicanos (Romo 2001, 103). The poster incorporates four gold, brown, and silver Kodalith images that form an archetype of early twentieth-century Mexican and Mexican American migrations. The photographs on which Rudy Cuellar based his poster are from his personal collection and represent both sides of his family, including his grandmother, uncle, and father, who served in the military during the Korean War (Terezita Romo, e-mail to author, January 30, 2014) (see plate 13).18

The images in Cuellar’s poster recall photographs by the Hermanos Mayo, posing a transnational, aesthetic link between Chicano/a serigraphy and 1940s Mexican photography. The Hermanos Mayo were Spanish photographers working in exile from the Spanish Civil War in Mexico City during the 1940s (Schmidt Camacho 2008, 75). Not regarded as “crafters of a visual record,” but rather as reporters, the Hermanos Mayo created the “most extensive visual record of the bracero mobilization” in pictures that exposed “the individual drama” (75, 76).

In Uprooted: Braceros in the Hermanos Mayo Lens, John Mraz and Jaime Vélez Storey (1996, 41–42) include several images from the Hermanos Mayo archive that show male braceros leaning out of train windows, grasping their children, and holding hands with their wives or mothers as they leave to work in the north.19 Mraz and Vélez Storey claim that the Hermanos Mayo provided “a human face to sociological data and statistics,” photographing the people who “actually experienced the events” (5). Rudy Cuellar’s poster parallels the humanization of Mexican workers in Hermanos Mayo photographs, but he pushes the viewing experience beyond the historical record by aestheticizing the people pictured.

In Cuellar’s rendering of a farewell scene, for example, a woman cleans a window, reversing the archetype in Hermanos Mayo photographs. Based on a picture of his grandmother, Cuellar accentuates her arm through color, signaling female labor—a representation of braceros that is uncommon in the Hermanos Mayo collection. The context of migration during the Bracero Program is underscored by the silhouette of a train traveling on a bridge below the woman. Cuellar uses the train to move the migration story forward in a composition that reads left to right and top to bottom.

In the next photograph, a man stands on a train dressed in apparel that suggests he is not a farmworker, but a railroad worker. This is an important detail in Cuellar’s poster because he is tied directly to the Mexican American diaspora created through the railroad in the early twentieth century. Cuellar grew up in Roseville, California, a small town northeast of Sacramento, and his father worked for the railroads. The photograph on which he based the image is of his uncle standing on top of a steam train. While the Hermanos Mayo “were emigrants looking at emigrants,” as Schmidt Camacho (2008, 75) notes, Cuellar looks at his family and arranges a visual narrative that moves across the geopolitical border, arriving not only in the agricultural fields but on the railroad tracks and in military service, which were critical parts of the Mexican and Mexican American migration story.

The lower left image, for example, shows two men sitting in a jeep in a field, with a small airplane parked behind them. While the plane can be read as a crop duster, the photograph is actually a snapshot of Cuellar’s father during the Korean War (Rudy Cuellar, Juan Carrillo, and Esteban Villa, conversation with author, February 3, 2015). Cuellar’s final image shows two of his relatives working on train tracks as opposed to laboring in farm fields. Captured in mid-swing, the foregrounded figures are framed by the shadow of a larger figure working on the tracks as the sun radiates in the background. The large, shadowy figure is residual, or an afterimage of their motion. Circular lines break off into fragmented streaks from the sun, indicating the intensity of the heat under which they work. By bringing the four photographs together, Cuellar creates what José Saldívar (1997, 29) calls “an alternative American Bildung,” or a different location for the “central immigrant space in the nation.” From a south-to-north trajectory, Cuellar disrupts the Eurocentric location of Ellis Island as the central immigrant experience in US history, illuminating Mexican American journeys to, and also within, the nation.20

The importance of the railroad in Cuellar’s poster resounds in the memories of other RCAF members, like Stan Padilla, who recalled the role of the railroad in moving his grandparents across geopolitical borders. Born in Northern California in 1945, Padilla asserted, “I was here before the Chicanos were even invented or came about,” when asked about his Chicano identity. “My family’s been here nearly one hundred years,” he continued, adding that the “first ones came to the valley. And so that was what a real Mexican American was. . . . With the [Mexican] Revolution, they came up” (Stan Padilla, interview, July 12, 2004). Resonating with the periodization put forward by Chicano historians in the 1960s and 1970s (as Emma Pérez [1999] contends), Padilla framed his family’s journey via the railroad at the turn of the twentieth century.

Padilla also broached the complexities of race and ethnicity in determining Chicano/a origins and identity when he noted the migration of his “Yaqui grandparents, [who] walked out. You know, with amnesty . . . you could ride the railroads. Before that, brown skins couldn’t ride the railroad. [But they] took the railroad . . . as far as you could go” (Stan Padilla, interview, July 12, 2004). The long walk of his Yaqui grandparents nuances the heroic journey of the Chicano/a family because it addresses the racial hierarchies between Mexicans and Native Americans who navigated the exclusionary policies of two nations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.21 While Mexicans and Mexican Americans were allowed to work and develop the railroads, indigenous peoples and phenotypically indigenous Mexicans were not allowed to ride them.

Stan Padilla’s rejection of the 1960s and 1970s as the beginning of Chicano/a identity troubles historical periodization that distinguishes between indigenous peoples and Chicanos/as according to geopolitical borders. Asserting his Yaqui ancestry as part of his Chicano identity, Padilla explained that his family arrived in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century and not as workers of the Bracero Program. Padilla’s arrival on the map of US history also responds to current tensions over undocumented immigrants or immigrants altogether in the United States, conveying that for many Chicanos/as who embraced Chicano/a identity in the 1960s and 1970s, indigenous ancestry continues to define their Chicano/a subjectivity.

Likewise, RCAF artist Irma Lerma Barbosa mapped the history of her Chicana identity through ancestral knowledge that subverts overarching geopolitical boundaries. Born in 1949 in Elko, Nevada, Lerma Barbosa recalled “the North Highlands area” of Sacramento and Roseville, California, where she was raised by her parents, Alejandrina Rascon Lerma and Saturnino Barrios Lerma, following their journeys from northern Mexico and Arizona. “My parents really couldn’t speak to other Mexicans,” Lerma Barbosa explained, “because they spoke an indigenous language as their primary language. The Spanish they learned was a mixture of caló, pochismos, English, and Spanish. My mother did teach us Spanish though. She was raised in the Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico, between Chihuahua and Sonora.” With only “an elementary school education, which was very advanced for a girl of her generation,” Lerma Barbosa’s mother held classes for her children. “After dinner, chores, and homework, all five of us kids attended Mama Nina’s school in our garage equipped with a beat-up chalkboard. She taught us Spanish, native dialect, and about honor and respect. My parents spoke Spanish fine, but with each other, they spoke their native language, and we grew up in a family language, which was that mixture of caló, indigenous words, and pochismos” (Irma Lerma Barbosa, interview, June 26, 2013). Lerma Barbosa’s memories of being immersed in a “family language” are seemingly contradictory because her parents spoke “Spanish fine” but had trouble speaking Spanish with other Mexicans. Yet she alludes to the reason for their linguistic difference when she mentions her family’s “migration path” through “Hermosillo, Aguas Prietas, Navojoa, Nogales, Douglas, El Paso, Juárez” (Irma Lerma Barbosa, e-mail to author, December 2, 2013). Influenced by sound, Lerma Barbosa maps a migration story through numerous accents, vernaculars, and regionalisms. She conveys her family’s history through what Rafael Pérez-Torres (2006, 107) calls “aural mestizaje” in his examination of Chicano/a and US Latino/a musical traditions.

Complementing the multilingual environment in which she moved, Lerma Barbosa added that her “father worked, first laying track from Mexico to Elko, Nevada, where I was born, then as a car inspector for the Southern Pacific Railroad” (Irma Lerma Barbosa, interview, June 26, 2013). Her father’s family was “settled near but outside of the Pascua Yaqui nation near Tucson.” Her mother and father “moved with the railroad and settled first in Nevada, then in Roseville.” Despite the family settling down, Lerma Barbosa recalled that her “mom would make yearly treks” to check on property, including a herd of cows that “my grandfather left her [when he died]. She would come back with huge slabs of dried beef and huge wheels of cheese manufactured by my mom’s relatives who cared for [the cows]” (Irma Lerma Barbosa, e-mail to author, December 2, 2013). Memories of her mother’s annual migrations and her family’s multilingual encounters chart an alternative Chicana history, or an oppositional consciousness to US history, since Lerma Barbosa is unconcerned with, as opposed to unaware of, US constructs of epochs and borders.

Furthermore, Lerma Barbosa’s memory of the home school in which her mother taught her children who they are (a point I underscore to recall the RCAF’s mural inside the Sacramento Concilio, Inc.) also rejects US history as a colonizing force in Chicana/o lives.22 By privileging her mother’s cultural and linguistic teachings over dominant ones, Lerma Barbosa suggests that her Chicana consciousness commenced through her mother, who pursued “intellectual and social justice” by transnationally structuring her children’s sense of family (Latina Feminist Group 2001, 26). Lerma Barbosa’s mother taught “homemade theories” to her children, which the Latina Feminist Group claims “propels the utopian dreams that have nourished us” and helps them “make sense of everything that we are and all that we find to love” (26). Through Chicana strategies of memory construction in oral history, Lerma Barbosa foregrounds her mother as a hero who informed her activism and agency in the Chicano movement. In doing so, she echoes Emma Pérez’s (1999, xv) “love of history,” which motivated her to decolonize Chicana history by using her own voice to articulate a third space in between the periodization of US and Chicano histories.23

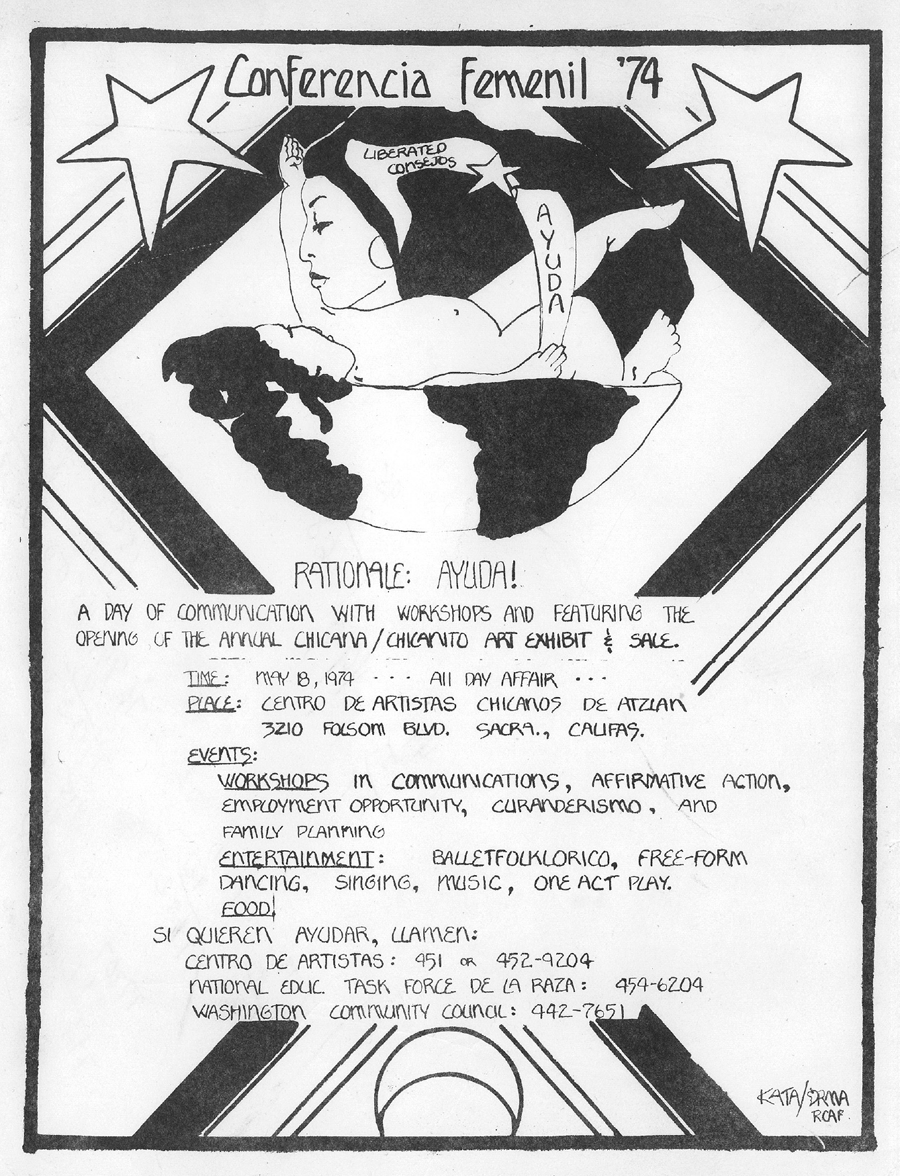

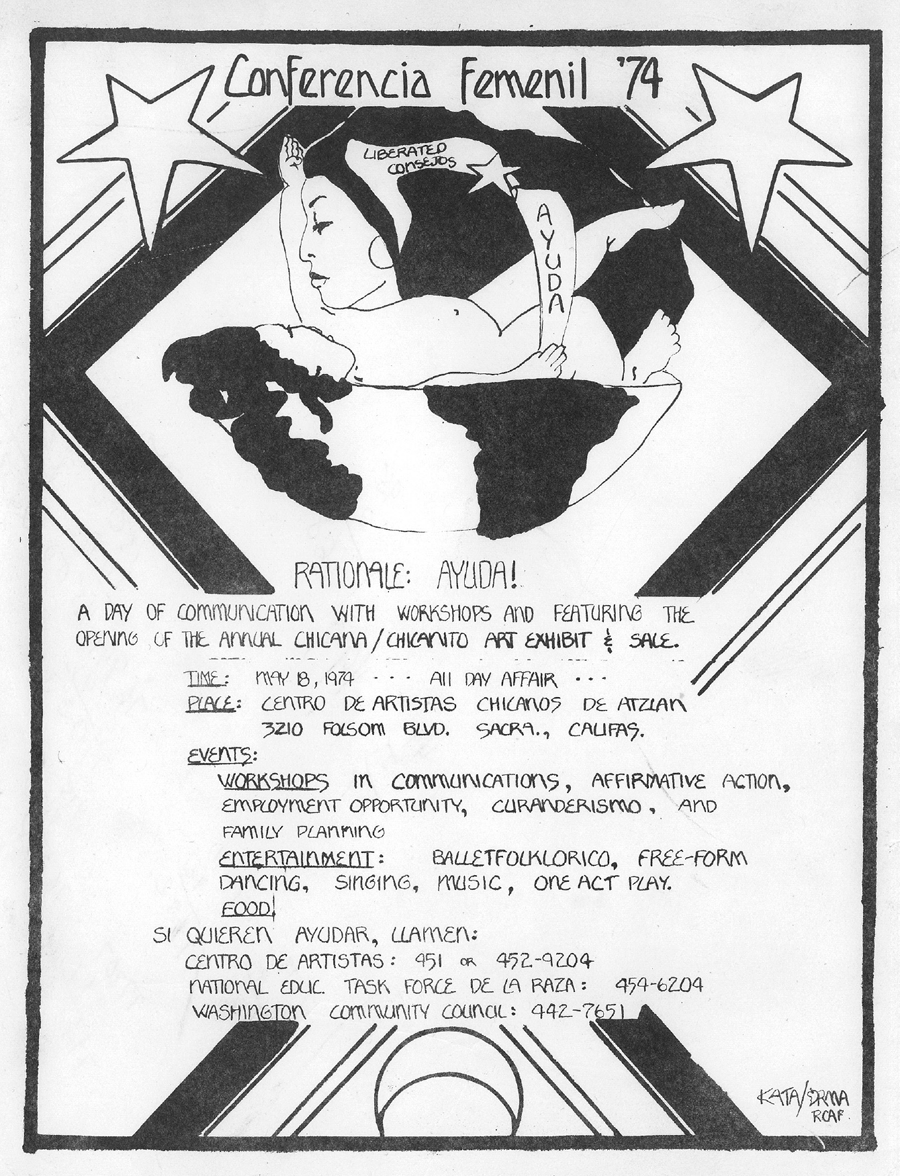

Figure 3.2. Flyer designed by Irma Lerma Barbosa and Kathryn García for 1974 Conferencia Femenil. Private collection of Irma Lerma Barbosa.

Irma Lerma Barbosa rejected the colonizing force of US history by upholding her mother’s teachings through her activism in the RCAF. Lerma Barbosa developed multiple images of Chicana identity that not only were symbols of female autonomy but reflected a Chicana community infrastructure that she was building for indigenous and female-centered knowledge. Working as a coordinator in 1974 for the National Education Task Force de la Raza, Lerma Barbosa planned and implemented the first Conferencia Femenil at the Centro de Artistas Chicanos. The day-long event included communication workshops with Chicana media professionals. Employment, affirmative action, and family planning workshops were offered to educate attendees about the opportunities and services available to them.24 Lerma Barbosa also planned a curanderismo workshop that instructed participants on the medicinal use of plants and herbs—a knowledge grounded in indigenous cultures and oral histories that was largely removed from Chicano/a consciousness through Spanish colonization and assimilation in the United States.

Led by Lerma Barbosa’s mother, Alejandrina, and another female elder, Alejandra Delgadillo, the workshop on herbal remedies and healing methods was a decolonial act that resonates powerfully in the flyer produced for the conference. Lerma Barbosa designed the image with her colleague Kathryn García, who created the Art Deco–inspired outline to which Lerma Barbosa added a woman holding a child. As the mother looks down on her child, the two figures’ hair cascades around them, transforming into a map of the Western Hemisphere and reflecting the mother-child image that Lerma Barbosa created in Women Hold Up Half the Sky (1975), a mural at Chicano Park. A ribbon with a star in the mother’s hair contains the Spanish words for freedom, advice, and help (Irma Lerma Barbosa, conversation with author, February 12, 2016) (see fig. 3.2).

Visualizing in the Collective Mode: Agosto 7 as Testimonio

There is a testimonio quality to the RCAF’s artwork that provides depth to the historical contexts in which Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and indigenous peoples navigated epochal change in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A literary genre that originated in Latin America, testimonio destabilizes Western understandings of autobiography and memoir by positioning an individual’s experience as “the reality of a whole people” (Menchú 2009, 1). Testimonio is a Chicano/a and Latino/a response to macroeconomic changes, wars, and geopolitical shifts that caused waves of immigration and diaspora (Jackson 2009, 96). The literal spreading of people, diaspora not only results from the push and pull factors of macroeconomic and political forces, it also results from exclusions in the mainstream culture and politics of the society in which displaced people rebuild their lives (Jackson 2009, 26). Subsequently, diasporic communities, Karen Mary Davalos (2001, 23) contends, “create alternative sources for establishing culture, memory and solidarity.” Testimonio is one such source, composing a narrative method that resists the erasure of subaltern experiences primarily through its collaborative mode. Testimonio is often spoken, relying on the storyteller and mediator (if translated for other audiences), which aesthetically determines it as a genre (Brooks 2005, 182). Pushing definitions of literary quality beyond Western notions, the performance strategies of the testimonio materialize “not as subversions of the genre’s social message but as vehicles of it” (182).

Returning to Rudy Cuellar’s calendar poster Agosto 7, he mixes photographs of his family’s experiences of migration, labor, and military service to aestheticize Chicano/a history before and during the Bracero Program, but the poster is not a fictive version of historical events, nor is it less authentic than photographs by the Hermanos Mayo. Resonating with Stan Padilla’s and Irma Lerma Barbosa’s memories of the role of the railroad in their family histories, Cuellar’s serigraph is a visual testimonio that accounts for intersecting mobilizations, separations, and experiences of Mexicans and Mexican Americans who had family members working on railroads, laboring on farms, and serving in the US armed forces prior to the Vietnam War.

The poem that Cuellar includes in Agosto 7 further supports the poster’s testimonio quality. The poem echoes the range of migration stories with musical cadence, propelling Mexican and Mexican American journeys through multiple spaces and times:

From Chihuahua, y

sabrán los dioses desde

donde before that, like scattered

leafs from an autumn

storm we drifted by rails

across make believe fronteras

del norte. From E. R., Dunsmuir,

Chicago, La Junta hasta de

Roseville, we layed cold

steel rails and sweated at the

round house, journing long

singing a song in search of

El Dorado—only to retire

and be swept away lost or

forgotten by company policy

now upheld by your sons and

daughters. Trabajadores

companeros les saludo.

Cuellar’s metaphor of “scattered leafs” articulates the displacement and disconnection of families during the Bracero Program, but for many families like Cuellar’s, the Bracero Program encompassed military service and railroad work, and families were scattered for different reasons. Misspellings in the poem are also important because they express a pronunciation of words, emphasizing the poem’s aural impact over its written one. “Journing,” for example, has one less syllable than “journeying,” maintaining the poem’s rhyme scheme but, more importantly, echoing the way the word is often spoken.

The poem moves in and out of historical epochs to ancestrally connect Native American peoples and sixteenth-century Spanish explorers with the Chicano/a experience. The lines “we layed cold / steel rails and sweated at the / round house, journing long / singing a song in search of / El Dorado” merge several historical moments and cultural encounters. Although roundhouses were specially designed buildings for servicing trains, aligning with the poem’s focus on the railroad as a central part of the Mexican and Mexican American migration story, the words “round house” also evoke Native American architecture—specifically the Miwok of Mariposa County in California, for whom the roundhouse is a ceremonial center for villages (Yosemite Online 2013). Meanwhile, the search for El Dorado, or a city of gold, symbolizes the hope for economic prosperity—a dream never realized for many Chicano/a rail workers who were “forgotten by company policy” and did not receive their contracted guarantees.

Cuellar’s reference to company policies that went largely unmet also corresponds with the historical reality of farmworkers. Working and living conditions for farmworkers contracted through the Bracero Program were deplorable. Promised minimum wages, adequate housing, insurance, the right to unionize, and the right to terminate employment at any time and return to Mexico, farmworkers found that these guarantees were largely unfulfilled by US employers (A. Garcia 2002, 31; Schmidt Camacho 2008, 69). Alicia Schmidt Camacho writes that “employers resisted the authority of the federal oversight and hired masses of unauthorized workers. Mexican laborers arrived to filthy work camps, encountering poor food, minimal care, and a hostile work environment” (69).

Born in Kingsburg, California, in 1944, Ricardo Favela grew up in the neighboring town of Dinuba. After Favela graduated high school in the early 1960s, his father told him, “‘You have two choices. You either continue your education or you come to work in the fields with me.’ . . . I went to college because I didn’t want to work in the fields. Now that’s a hell of a way to go to school. . . . . And my mother was always telling me, ‘Son, get a job in the shade. Just get a job in the shade’” (Ricardo Favela, interview, July 20, 2004). A “hell of a way to go school,” Favela worked in agricultural packing sheds prior to his graduation and after years of fieldwork alongside his family.

In an interview conducted at California State University, Sacramento, Favela speculated on his father’s immigration from Durango, Mexico, to the United States: “I have a sneaking suspicion that he came in as a bracero, in the forties and fifties perhaps, and was able to attain a green card” (Schraith 2001). Finding work in California’s fields and eventually as a truck driver, Favela’s father met his mother in the San Joaquin Valley. The youngest of eleven siblings, Favela moved with his family around the small towns of the area, following the crop seasons (Schraith 2001). The only one of his siblings to graduate high school, Favela acknowledged that the task had not been easy, but he believed it was a critical step in escaping the circumstances that many young Chicanos/as faced in farmworking communities: “I realized that the majority of my peers were destined for an existence of drug or alcohol abuse, prison time, or a lifetime of grueling work in the farm fields. This epiphany was the catalyst that motivated me to continue my education, in an effort to break free from this predetermined path” (Schraith 2001).

Descriptions of “the predetermined path” were a common reflection for RCAF members whose childhoods took place in the fields. Born in Lincoln, California, in 1945, to Jesus and Carmen, Juanishi Orosco recalled, “We were farmworkers; our parents were farmworkers, and we knew what the conditions were” (LaRosa 1994). RCAF member and former Sacramento mayor Joe Serna Jr. adds, “My father died not knowing what it meant to earn over a buck and a quarter an hour” (LaRosa 1994). Along with abysmal camp conditions, farmworkers were exposed to pesticides like DDT as crop dusters sprayed fields while people picked crops from dawn to dusk (LaRosa 1994).

Esteban Villa described the farmworker experience as “unrelenting hunger and deprivation that trapped me into a corner of life and it forced me to fight my way out by using my creativity” (Quirarte et al. 2004). Literally meaning “one who works with his arms,” the bracero’s “hunger and deprivation” extended far beyond basic survival needs, as Villa’s description suggests. Born in Tulare, California, in 1930, to Antonio and Serafina, Esteban Villa connects the isolation he felt as a child to his educational desires. Unsure “if they could read or write,” Villa recalled that his parents “knew they were supposed to keep children in school . . . and they didn’t force me out. I raised myself more or less because they were always working in the fields. In the morning they’d be gone, and they’d be gone at night when I’d be sleeping” (Esteban Villa, interview, January 7, 2004). Villa’s recollection imparts the deeper toll that the conditions of farmwork had on children through the demands it made on parents, depriving entire families of intimate connections.

Villa’s reflections also convey that he desired more life options, and not simply better housing, wages, and protections under the law. Young Chicanos/as like Villa wanted to do something else with their lives: “I think it was the importance of school—for whatever reason, it was better than home. I had schoolwork, art supplies, and field trips. I loved it” (Esteban Villa, interview, January 7, 2004). Desire to do more with one’s life is a constant theme in the heroic allegories that the RCAF used in their art. From political desire for labor equality and civil rights to pride in a pre-Columbian past and ancestry, the RCAF’s decolonial vision hinged on a universal theme of a meaningful existence through historical connection, education, and political visibility.

The “Many Wests” of the Heroic Chicano/a Family

As the labor relationship between Mexico and the United States shifted throughout the twentieth century, the predominance of Mexicans in the US agricultural sector was pushed by economic hardship and population displacement after the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and pulled by the enactment of the 1942 Bracero Program. It is also important to note that during this time, many Mexican Americans, Hispanos/as, Tejanos/as, and indigenous peoples internally migrated to urban areas in the US Southwest. Racial hostility in the United States was a push factor for Mexican Americans who entered a binational worker program alongside Mexicans, as the US and Mexican governments implemented a policy to ensure a steady supply of immigrant workers (A. Garcia 2002, 31).25 Anti-immigration sentiment and changing immigration policies in the United States impacted existing communities during the Bracero Program. Deported in the 1930s amid the Great Depression, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were later “imported,” Harry Pachon and Joan Moore write, due to labor shortages caused by World War II; they were then deported in large numbers in the 1950s through Operation Wetback (Pachon and Moore 1981, 114). Further, the regulation of the Bracero Program was never complete, and subsequently, Mexican Americans moved internally in the United States for work opportunities during and after World War II. Resettlement also coincided with a movement of people out of Texas in the 1940s due to the dangerously xenophobic environment (Pachon and Moore 1981, 114). Thus, geopolitical changes to the US-Mexico border in the nineteenth century coupled with twentieth-century immigration laws reshaped legal definitions of Hispano/a, Californio/a, and Tejano/a nativity in the United States. “The first Mexican-descent workers to migrate internally within the United States as mobile seasonal laborers were neither foreigners nor Mexican immigrants,” Antonia Castañeda (2001, 120) writes, adding, “they were Californios, Tejanos, Nuevo Mexicanos, and native-born US citizens made exiles, aliens, and foreigners in their native land.”26

Castañeda’s point resonates in José Montoya’s memories of his family’s migration from New Mexico to California. The uniqueness of Montoya’s family history does two things to the collective mode in which the RCAF visually exalted the Chicano/a family in their artwork. First, it accounts for the impact of the Bracero Program on preexisting Mexican American communities and exposes the complexities of people living with constructions of race under two competing colonial orders. Secondly, it discloses that Chicano/a identity in the 1960s and 1970s was a political choice and an act of agency for people who were labeled and reclassified for at least two centuries in the United States by systems beyond their control.

Montoya’s memories rely on a family-centered axis that pivots with and against a Chicano/a history that responds to colonial moments in US history. Not a native Californian or born in Mexico, Montoya was born in New Mexico in 1932 and migrated with his family for the first time to California in 1941 (Romo 2011, 13). He recalled that some of his New Mexican relations “never have been traced to Mexico at all, but they’re Mexicans from when [Mexico] was known as New Spain.” Montoya continued,

For all intents and purposes, those mountains of New Mexico were really all the Montoya family knew and understood. . . . The ones that came from Chihuahua came at the beginning of the [Mexican] Revolution. . . . Some claimed Apache, Pueblo, and Castellano. . . . Some of my relatives claim Hispano. I claim more of the Chihuahua Mexicano—that we were Mexicanos. You know, some parts of my relatives would cringe at that word. I had a step-grandfather who was a justice of the peace, [and] he would say, “There’s nothing Mexican about the Hispanos. They are indigenous mixtures. It was Apache or Pueblo.” Yeah, it was an interesting mix. But when we first came to California, we realized it was a different mixture. . . . There’s more Mexican-ness than Spanish-ness. And in Hanford, California, in school, they thought I was Portuguese. And we were amazed that what was the Portuguese language was Spanish. But I was never able to pick it up. (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004)

Covering five centuries of conquest, migrations, and racial mixtures, Montoya claims his ancestry as his connection to a nonimmigrant population in the United States. By “nonimmigrant population,” I refer to the outcome of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed after the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), which changed the geopolitical borders between the United States and Mexico and in turn, the legal statuses of preexisting populations in the areas that became the US Southwest.

While some of Montoya’s ancestors “would cringe” at being called Mexican, he acknowledges their position, despite his personal preference for the “Chihuahua Mexicano” to convey the particularities of his ancestry and its preexistence in the United States. But how did Montoya’s grandfather arrive at the conclusion that “there’s nothing Mexican about the Hispanos”? Why would some of Montoya’s relatives “cringe at that word”? Montoya’s “interesting mix” of family, or their differing identity politics, reflect larger processes of Spanish colonization and nineteenth-century antimiscegenation laws in the United States that (re)racialized regionally distinct populations. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, Spanish and Mexican governments established communities that comprised colonists and local indigenous populations, developing distinctive racial and ethnic mixtures and cultures in the northern territories that became the US Southwest (Menchaca 2007, 315). But once the United States “acquired Mexico’s northern frontier,” Martha Menchaca writes, “the multiracial ancestry of the conquered Mexicans placed them in an ambiguous social and legal position” (315).

Preexisting populations, Martha Menchaca writes, “entered a new racial order in which their civil rights were limited and were determined by their blood quantum,” a process reflecting the US slavery system as the US Civil War approached (316). But “throughout its history,” Menchaca explains, “New Mexico chose not to pass anti-miscegenation laws” (318), which potentially explains Hispano/a acceptance (and pride) of a blended Spanish and indigenous heritage, as well as Montoya’s memories of his grandfather’s claim that “there’s nothing Mexican about the Hispanos. They are indigenous mixtures” (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004). Montoya’s emphasis on his Hispano roots as native heritage responds to two levels of colonization (Jackson 2009, 87), which Montoya invokes to historically contextualize himself as one of the “native born US citizens” that Castañeda (2001, 120) asserts were present in the area that became the US Southwest.

When Montoya and his family migrated to California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1941, they became part of a labor force that reflected “more Mexican-ness than Spanish-ness.” His family had been cattle ranchers and subsistence farmers in the mountains of New Mexico (José Montoya, interview, July 5, 2004). Class hierarchies of Spanish, then Mexican, rule turned into racial and linguistic ones once New Mexico became part of the United States. Rafaela Castro (2001, 124) explains that “the Spanish language spoken by the Hispanos maintained an antiquated quality for hundreds of years because of isolation in the region.”

The misreading of Montoya’s ethnicity in California’s San Joaquin Valley during the 1940s exemplifies the impact these different phases of colonization had on the Mexican American diaspora and the historical, linguistic, and cultural particularities they elided. Montoya was not recognized as New Mexican nor “read” as Hispano. Instead, “they thought I was Portuguese,” in part because of the large community of Azoreans who settled from the nineteenth century to the 1970s in the rural communities of California’s San Joaquin Valley (Reese 2003).

Yet one of the discernible traces of the history of wars, annexation, resistance, and cultural adaptation was acoustic for Montoya, who could hear the Spanish in the Portuguese; after all, his language had originated in a Hispano/a context.27 The complexities of his colonial encounters with different racial orders are, ironically, eclipsed by a Chicano/a history that is periodized only in response to the colonial moments that Emma Pérez (1999) critiques. Great events in Chicano/a history that adhere to US history’s timeline transpose an “overarching theory about power relations and culture belonging within the hemisphere,” Chon Noriega (2012, 4) writes, producing “generalizing conclusions” about a transformational epoch and the people who lived it. Montoya’s memories, like those of Irma Lerma Barbosa and Stan Padilla, return a sense of the diversity—or the many voices—of the collective Chicano/a experience, revealing that there were many Wests, which Noriega (1995, 12) describes as a multitude of experiences “located at the crossroads of conflicting historical perspectives.”28

Responses to competing colonial orders and their impact on preexisting populations were visually redressed by RCAF artists. Juanishi Orosco created Viva la Huelga (1977) for the RCAF’s Historia de California calendar, accounting for the indigenous peoples who worked alongside Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the Bracero Program.29 Flags, in a national context, are hegemonic symbols of citizenship and demographic cohesion. But Orosco uses a United Farm Workers (UFW) flag to exalt the idea of a native coalition. The visual scene consists of farmworkers who are separated by frames but nevertheless connected through the UFW flag. An indigenous man is depicted within the smaller frame but is the largest figure in the poster; his arm and hand extend beyond the frame that borders him and move into the central image. The UFW flag he holds blankets the sky under which three farmworkers stand. A campesino holding a smaller UFW flag over his shoulder and a female farmworker flank either side of an indigenous man’s portrait (see plate 14).

The inscription in the calendar image emphasizes the human rights of the farmworker, and Orosco positions the UFW flag both with and against dominant histories of war and colonial claims to territory. As an emblem of labor solidarity for the UFW, the farmworker flag is used in Orosco’s poster to imagine a “state” of sovereignty for colonized peoples through a visual culture of labor. The idea conveyed in the poster is a decolonial one, taking place between that which is colonialist and that which is colonized, and reflecting a conscious choice to center Chicano/a identity on the commonalities of colonized peoples with fragmented histories, fighting together toward a shared goal.

“The sounds of those nights en carpas”: The Heroic Farmworking Mother

The farmworkers who participated in the Bracero Program were racially, ethnically, linguistically, and regionally diverse, but a central commonality that affected them concerned patriarchal gender roles, which translated into the gendered divisions of labor across Mexico and the United States. Growing up in a migrant family, Antonia Castañeda (2001, 130) remarks bluntly that farmwork “was hierarchical, stratified by race and gender. . . . Women were paid less than men, Mexicans were paid less than Anglos, and Mexican women were paid least of all.” Castañeda’s observation echoes in Ricardo Favela’s recollections of his mother. Born in San Diego, California, Favela’s mother “spent much of her life enduring the hardship of domestic labor before working in the fields, and later as a labor camp cook” (Schraith 2001). The advice Favela’s mother gave him on how to navigate labor conditions came directly from her experiences with the patriarchal system under which farmwork operated. Preferring to cook “because she was under shade and didn’t have to go out in the fields,” Favela’s mother shared her survival strategy with her son as he made his future plans (Schraith 2001).

Meditations on the gendered divisions of labor resound in José Montoya’s 1969 poem “La Jefita,” which visualizes the inequity of women’s work through sound. “When I remember the campos,” he begins,

Y las noches and the sounds

of those nights en carpas o

Bagones I remember my jefita’s

Palote

Click-clok; clik-clack-clok

Y su tocesita. (J. Montoya 1992, 9)

Taking his audience inside the family tent, Montoya conjures an image of his mother cooking at night as he is awakened by the noises she makes. He asks, “¿Que horas son, ’ama?” to which his mother replies, “Es tarde mi hijito. Cover up / Your little brothers. / . . . Go to bed little mother! / A maternal reply mingled with / The hissing of the hot planchas” (9). “‘La Jefita,’” José E. Limón (1992, 96–97) asserts, is a “muted rebellion and pro-maternal stance” against the subjugated reality of the farmworking family. Preparing lunches to sustain her family during their next day of hard labor, la jefita literally works against the conditions of the camp.

In focusing on the sounds of his mother’s labor, Montoya broaches the politics of the domestic sphere, or who works within the home and who benefits from those efforts. Amid “the snores of the old man,” Montoya swears his mother “never slept!” (J. Montoya 1992, 9). Aída Hurtado (1996, 65-67) claims that “La Jefita” is an ode that pastoralizes the Chicana farmworker-mother, obscuring her exhausting reality through the constant sounds of her labor. Montoya, for example, begins the morning scene by being jolted awake by his father’s whistle “that irritated the world to / Wakefulness. / Wheeeeeeet! Wheeeeeeet!” Montoya next hears his father’s menacing command, “¡Arriba, cabrones chavalos, / Huevones!” to which Montoya humorously interjects, “Y todavia la pinche / Noche oscura.” In the background of his clamorous wake-up call, Montoya hears “la jefita slapping tortillas” as she orders her daughter, “¡Prieta! Help with the lonches! / ¡Calientale agua a tu ’apa!” (J. Montoya 1992, 9). The authority with which Montoya’s mother commands her daughter to help with the chores is part of her “legitimate” domain, or the domestic space, according to Hurtado (1996, 65), who claims that Montoya idealizes motherhood to foreground “the family centeredness that characterizes Mexicano/Chicano culture.”

While la jefita is the center of care for the family, her “silence is a direct measure of her sainthood,” Hurtado claims, since “she does not express needs, pains, or frustrations” (67). Although Montoya’s exaltation of his farmworking mother is well intended, Hurtado concludes that he converts her into the “other” (67). But one wonders if Montoya actually “others” his mother or, to borrow Guisela Latorre’s (2005, 100) phrase, participates in the “mythification of women” in a poem that in reality is about his mother Lucia Montoya. If “La Jefita” strikes a “chord of truth for many working-class Chicanas and Chicanos” regarding self and group preservation through the constant work of women (Hurtado 1996, 67), perhaps it does so because of its testimonio quality.

In other words, the poem does not dehumanize, but rather relates the dehumanization process under which Chicana farmworkers lived and worked in inadequate housing, with limited access to supplies, and under conditions that were (and are) hostile to the Chicano/a family’s well-being. The sound of her labor, then, is a subaltern response to a system of oppression. The sounds aurally symbolize her efforts to treat her family humanely and restore their humanity through sustenance and care. This is a point that Limón (1992, 96) makes by locating “La Jefita” at “the heart and hearth of this dominated universe, mitigating its corrosive effects with her nurturing familial love.” Domestic care for one’s family is a decolonial act that resists the destructive forces of labor exploitation. Rising in the middle of the night to make breakfast and prepare lunches, la jefita then carries a hundred pounds of cotton from the field as Montoya’s father smiles in awe of her, remarking, “That woman—she only complains / In her sleep” (J. Montoya 1992, 10), which apparently is never, since she works at night in preparation for the next day. With her commanding hushes to her son to go to sleep and her direct orders for her daughter to bring hot water to her father, la jefita is not a metaphor of selfless motherhood; she is a tenacious woman combatting exploitive working and living conditions to defend the human rights of her family.

Further, la jefita is not silent in the poem; readers and listeners hear her tell Montoya to cover his brothers and go back to sleep; they hear her orders to her daughter during the morning routine. While audiences are mostly aware of her through the sounds of her labor, sound is everywhere in the poem, suggesting that Montoya invokes the working-class pastoral ironically. The audibleness of “La Jefita” is central to the poem’s purpose. From the “PRRRRRRRRINNNNGGGGGG!” of the “noisy chorro missing the / Basín” to the “Wheeeeeeet! Wheeeeeeet!” of his father’s whistle (J. Montoya 1992, 9), Montoya records sounds that are not necessarily recognizable outside the labor camp. If “La Jefita” is an allegory, it pertains to the class politics of sound, or what sounds like home in a labor camp and inside a tent, what sounds like work in a crop field, and who and what is audible in both spaces, all of which are accounted for in the poem.30

The War at Home and the War Abroad: Chicano/a Veterans

While the sound of his mother’s labor in the family tent conveys José Montoya’s experiences of farmwork in the 1940s, not all members of the RCAF grew up in California’s agricultural fields. Like Irma Lerma Barbosa and Rudy Cuellar, RCAF artist Juan Cervantes grew up in a railroad family. He recalled, “Rudy and I went to high school together [and] to elementary school [in] Roseville. . . . When I talked to him about going back to school instead of working in the railroads like our dads were, we went to Sierra [College]” (Quiñones and Flores 2007). Stan Padilla simply asserted that his family “didn’t really do farmwork. Roseville, Lincoln, all over that area is all the canneries, and the dry yards in Elverta, but mainly it was the canneries” (Stan Padilla, interview, July 12, 2004).

Members who did not grow up in farmworking families were also from cities, like Juan Carrillo, who was born in Mexico and raised in San Francisco. At a 2007 roundtable discussion held in the University Library Gallery at California State University, Sacramento, RCAF artists gathered to discuss their history. Juan Carrillo lightheartedly teased his colleagues about the regionalism they attach to the RCAF and, more broadly, to the Chicano/a movement. In doing so, he provided insight into the formation of a self and group identity for a Chicano/a art collective. “I’m a San Francisco guy,” Carrillo explained. “I come here and I start to meet all these valley guys, and they just—they were insufferable (Quiñones and Flores 2007). Amid the laughter, Carrillo continued, “I listened to all this stuff about farmworkers, and, you know, the real Chicano/a comes out of the valley. The education happened outside of the classroom at Berkeley and it continued here . . . the whole reanalysis of things, including what is art, what is history, what is sociology, what is anthropology if it doesn’t consider our experience, our reality” (Quiñones and Flores 2007). Challenging the notion that “the real Chicano comes out of the valley,” Carrillo alluded to interracial and cross-cultural collaborations at UC Berkeley, which largely shaped urban manifestations of the Chicano movement. His witty but reflective comments signal that regional and working-class differences were negotiated during the 1960s and 1970s Chicano movement. Not all Chicanos/as who supported and participated in the United Farm Workers union were farmworkers, and not all Chicanos/as who protested the Vietnam War were veterans. Necessary amid the crises of total societal exclusion, Chicano/a cultural nationalism condensed differences to unify a civil rights movement.

Other RCAF members who were not originally from cities lived for periods of time in Los Angeles. These members served in the armed forces during the Vietnam War, using the GI Bill to pursue higher education. Upon his honorable discharge from service during the Vietnam War, Armando Cid did not return to Sacramento, where he had been raised after being born in Mexico (Josephine Talamantez, conversation with author, January 11, 2016). Instead, Cid wanted “to get into art school,” he explained, adding that he “went to the Art Center College of Design” in Pasadena, California, where he “was the only Mexican on the whole campus” and worked at night for the Los Angeles Times as a copy editor (Quiñones and Flores 2007).