Observing Behavior

Perception and Misunderstanding

To perceive means to immobilize . . . we seize, in the act of perception, something which outruns perception itself.

HENRI BERGSON, French philosopher

However, no two people see the world in exactly the same way. To every separate person a thing is what he thinks it is—in other words, not a thing, but a think.

PENELOPE FITZGERALD, British author

Like many other college professors, I am occasionally asked by local newspapers, radio, or television stations to comment on events that I might know something about. Like most people who talk to reporters, I do so with a certain amount of apprehension, as the result of having been misquoted in the past. Although I learned quite early in my career to be leery of newspaper interviews, for a while I naively assumed that a television interview would be less dangerous. After all, you can’t be misquoted when you’re there on the screen saying the words yourself. I quickly realized the error of this logic, however, when after my very first television interview key parts were edited out; the result was that I appeared to have said almost the exact opposite of what I had actually stated during the interview. I’m sure the news editor did not intentionally distort my message, but that is exactly what happened in the course of condensing a fifteen-minute interview into a two-minute sound bite. At the time, I was certain that if the entire interview had been telecast, no one would have misunderstood my intended message. I was wrong. Many of us watch the evening news in the midst of numerous distractions—dinner is being prepared, the children are asking about the dinner that is being prepared, the family pets are demanding that their dinner be prepared, other adults are talking about their day or asking about ours. In the midst of such distractions, we are unlikely to hear or pay attention to every word being broadcast on the tube. Under typical circumstances, many people would have missed part of and thus misunderstood my message even it had been broadcast in its entirety.

The problem is not unique to television viewing. At any moment in time there is just too much going on for us to possibly take it all in, and many misunderstandings are the result of this fundamental and unavoidable dilemma. Unlike video or tape recordings, human observation involves much more than a simple capturing of information. We not only gather information, we process it as we are gathering it. To make it even more complicated, during social interaction we do all this while simultaneously interacting with the people who are the sources of that information. At minimum, therefore, human observation involves two complex processes—perception and interpretation. Generally speaking, perception involves how and what we notice in our environment and interpretation involves how and what we think about the things we notice. Both processes are involved in formulating our understandings of each other.

I’ll See It When I Believe It: The Influence of Expectation on Perception

At first blush, the title of this section appears to be a misquote or misstatement of the skeptic’s aphorism I’ll believe it when I see it. If so, it is a misstatement of which Freud would have been proud, for there is considerable scientific evidence that in a sense we see only what we already believe to exist. In fact, the primary theme of this chapter is that not only is seeing believing, but what is seen or heard sometimes depends on what is believed.

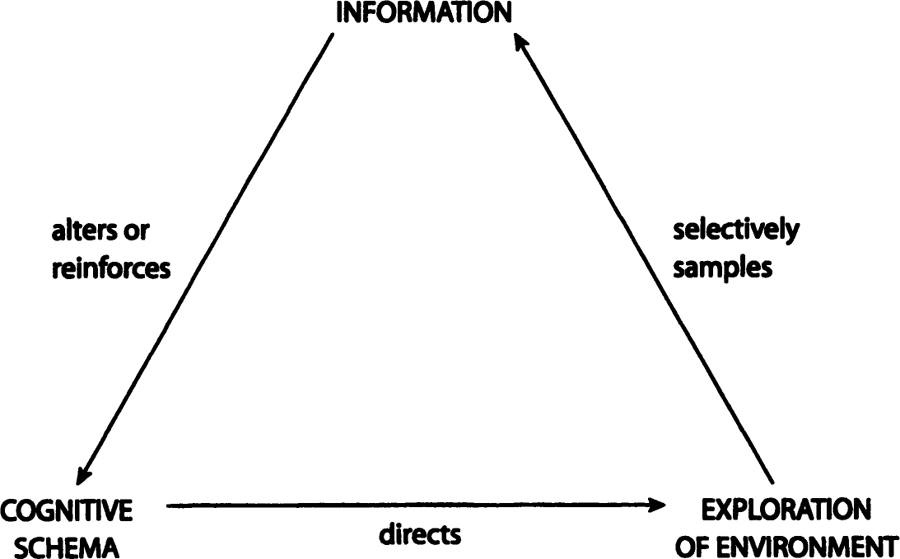

To see why this is, we need to understand something about how human perception works, for all understanding is rooted in perception. Unfortunately, perception is not simply a matter of opening our eyes and ears and taking in what is out there; it is an active process of selectively seeking out certain information. In fact, according to psychologist William Powers (1973), virtually all of our actions are geared toward controlling our perceptual experiences. If I perceive that it is starting to rain, I head for shelter. If I perceive an unexpected but familiar voice, I turn toward it. If I perceive that the hole I am digging is not yet deep enough, I keep digging, but if I perceive that my limbs are getting tired and weak, I dig more slowly or take a break from digging and sit down. If I perceive a hunger in my gut, I either move toward acquiring food or the purely mental action of talking to myself about waiting a while to eat. If I perceive that the person I am listening to is saying something I am interested in I listen more attentively, and depending on what I hear next, I’ll keep listening carefully or allow my mind to wander to other things. My perceptions influence my actions and my actions influence what I perceive next. Thus, as Figure 1 shows, perception is an ongoing interaction between the individual and the environment in which the perceiver actively seeks out certain information from the environment and uses that information to direct further exploration (Neisser 1976). Because of the tremendous amount of sensory information available to us at any given moment, however, we have no choice but to selectively focus our attention on certain things at the expense of others.

The mental or cognitive structures that utilize perceptual information from prior experience to generate future expectations are referred to as “cognitive schemas.” As we collect sensory information we process it in ways that are consistent with what we already know or believe to be true. When we encounter a similar situation in the future, particular cognitive schemas are triggered. These schemas allow us to anticipate certain events in the present situation, and our attention again will be guided by those anticipations or expectations. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, perception is an ever-evolving process in which the information to which our schemas direct our attention either reinforces the relevant schemas (if what we perceive is consistent with our expectations) or alters them if our perceptions are inconsistent with them. Thus precisely what we see when we look and what we hear when we listen depends on what we expect to see or hear. For example, although many people report having seen the “man in the moon,” I have yet to find anyone who claims to have seen it before they were told that it was there and therefore were primed to look for it.

Figure 1. Model of the Perceptual Process (Adopted from Neisser 1976)

Most perception is less consciously focused than the act of looking for the man in the moon, however. Once we have schemas for certain things, we do not have to consciously think about those things for the relevant schemas to be activated. For example, most of us can drive to work without getting lost or unconsciously running through any traffic signals, even if we are completely absorbed in thinking about something else. This is because we are familiar enough with the streets we travel to accurately anticipate traffic signals on certain corners, even if we are paying very little attention to our driving. In strange cities or unfamiliar parts of our own town, however, we don’t know what to expect as we round each comer. Thus, even though we might be paying more attention there, we are more likely to cruise through an unnoticed red light.

Despite the powerful influence of expectations on what we are able to perceive, however, our schemas do not completely blind us to unexpected information. Although we will more easily notice things that are consistent with our expectations, we are certainly capable of eventually seeing or hearing things we don’t expect, especially if those things are dramatically different from what we expect. We might not notice a fresh coat of paint on a friend’s house, but we would notice if a new wing had been added. It is also possible to sense that something is not quite right without being able to identify precisely what is wrong, and sometimes we even see or hear things that aren’t there.

Confusion of this sort is the result of a distortion of perception. Such distortions were the subject of a classic experiment conducted back in 1949 by Bruner and Postman. Using an instrument similar to the one an optometrist might use to test your vision, they presented subjects with very brief views of ordinary playing cards. Interspersed with the normal cards, however, were incongruous cards, such as red spades or black hearts. Initially subjects tended to identify the incongruous cards as normal, misidentifying either the color or the suit. Upon repeated exposure, however, many subjects began to notice that something wasn’t right, but they tended to have what Bruner and Postman called “compromise reactions.” Red spades were reported as brown, black and red mixed, or a number of other possible compromise colors and mixtures. As viewing time was increased accuracy was greatly enhanced, and when given enough time the subjects were eventually able to correctly identify the incongruous cards.

Given the highly selective nature of perception, it is easy to see how two people could experience the same event and come away with very different perceptions of what has occurred. This often happens when people are listening to music lyrics; although they are hearing the same song, they hear different words. In a humorous little book about this phenomenon, ’Scuse Me While I Kiss This Guy, Gavin Edwards (1995) gives dozens of examples of commonly misheard lyrics. Not only do our ears seem to hear different things, our eyes often seem to see different things, even when we are witnessing the same event. Notice how often sports fans argue over whether a base runner is safe, a receiver is out of bounds when he catches a pass, or a collision on a basketball court, hockey rink, or soccer field is the result of a defensive or an offensive foul. Observers of feuding fans might reasonably wonder whether they have been watching the same game. Clearly, things are not always as they appear, and often we are poorly prepared to distinguish what really happens from what only appears to happen.

Social Perception: People and Situations

So far, this discussion has focused primarily on perception of the physical world, but you might already have realized that the perception of the social world of people and their actions works the same way. Just as the drive to work activates a schema that helps us navigate the physical world, so certain social cues activate schemas that are used to navigate the social world. Upon entering our places of work each morning, we are immediately prepared to hear the familiar greetings and see the familiar facial expressions of our co-workers. After a while our expectations of these daily rituals become so strongly entrenched that we probably would not even notice a casually stated “good evening” instead of “good morning.”

I recently had a social experience analogous to the playing card experience of Bruner and Postman’s (1949) subjects. I was at home anticipating a phone call from a friend. When the phone rang I answered and heard the expected voice on the other end. However, several seconds into the conversation I realized I was not talking to the person I had expected. Because I was anticipating one voice, I literally heard the voice on the phone differently from how I otherwise would have. Although I remember thinking the caller sounded a little different from usual, I did not initially perceive that I was actually talking to a different person.

Our expectations influence the way we perceive others in countless ways, and our expectations are often far from rational. In an interesting study of how irrational expectations influence perception, Mark Frank and Thomas Gilovich (1988) discovered that people tended to rate professional sports uniforms that were at least half black as being more “bad,” “mean,” and “aggressive” looking than others. When the experimenters showed the same aggressive football plays to a group of trained referees, the referees rated the plays as more deserving of a penalty when the aggressive players were clad in black than when they were dressed in white. These authors also noted that hockey and football teams that wear black have been penalized significantly more often than others. Thus it appears that even professional sports referees, who are selected on the basis of their ability to be objective, were influenced by the irrational, and no doubt unconscious, expectation that players wearing black would be overly aggressive in their play.

Just as we have schemas of people and things, so we have schemas of situations, which influence the way we perceive people and their actions in those situations. Situation schemas are activated by what sociologists call “definitions of the situation.” Referring to situations by names such as “birthday parties” or “business meetings” activates schematic images that lead us to define those situations in particular ways. Those definitions include fairly specific expectations of (1) what kinds of actors will be present, (2) what kinds of actions they will be engaged in, and (3) how we will fit ourselves into the overall sequence of events. For example, we know that a birthday party usually involves three types of actors: the person whose birthday is celebrated, the person or persons who host the party, and those who attend. We also know that certain actions will be part of the situation. Food will be served and eaten, presents will be given and received, and a happy birthday song will be sung. With only slight variations, all these characteristics of the situation are defined by the culture we live in and will be present regardless of whose birthday is being celebrated or who attends the party. Such cultural expectations are only a part of the individual’s definition of the situation, however, for each individual who attends will have his or her own personal orientation to the occasion. Some people like birthday parties, others do not; some see a party as a chance to relax and have fun, others as a chance to make new business contacts; some treat gift selection seriously and spend hours looking for just the right thing, others feel comfortable slipping a check or cash into a card.

Both cultural and personal definitions influence our expectations in all social situations, and these definitions enhance our perception of some things and limit our perception of others. The power of cultural definitions to limit our ability to perceive is illustrated by the following riddle.

A young boy and his father were out for a drive when they were involved in an automobile accident. An ambulance arrived quickly and took them to the hospital, where the father was pronounced dead and the son, who had sustained serious injuries, was rushed into surgery. Just before the surgery was to begin the surgeon looked down at the boy and exclaimed, “I can’t operate on this boy; he’s my son.”

How is this possible? Although the answer is revealed by the use of simple logic, many very intelligent people are at least momentarily stymied by it. As we listen to stories like this we develop a mental image of the situation being described and the actors involved. Because in our society the medical profession is dominated by males, the image of the male surgeon leads many of us to overlook the obvious fact that the surgeon in this story must be the boy’s mother. Thus, our rather rigid schematic image of an operating room figures so prominently in our thinking that we overlook the obvious.

Once a situation schema is activated, the mental image that produces it is often so vivid and detailed that we assume we know exactly what to expect. As a result, we overlook or fail to pay attention to information that does not fit that image. The following misunderstanding is the type that often results from such a failure.

The last misunderstanding that occurred was about two months ago. I told my friend that I would pick him up from school on Friday. I have a white Buick and my sister has a gray Sentra. We decided to take one car home that weekend, and we took my sister’s. When I went to pick up my friend, he never showed up. I finally went around the campus looking for him and found him. He asked if I was late because he couldn’t find my car. I then realized that maybe he didn’t know what my sister’s car looked like and that is why he couldn’t find it He told me that I said I was going to be in my car, but I thought I said that I would pick him up in my sister’s car. It was a misunderstanding because we were not clear on what car I was going to bring.

There is no way of knowing who was at fault for this misunderstanding, but if it was a common occurrence for the narrator to use his car to give his friend a ride, the friend probably had a fairly vivid schema for that situation, which was activated as soon as the narrator agreed to pick him up (or perhaps even before the phone call was placed). If so, expecting his friend to say, “OK, I’ll pick you up in my car,” as he had in the past, he might easily have failed to hear the word “sister’s.”

Social situations are not always as predefined and ritualized as a birth-day party or medical operation. Most are created spontaneously in the course of interaction, although once created they often take on a character of their own that influences our expectations of each other. You have probably at some time found yourself seated beside a stranger on a plane, bus, or train. One of you might have struck up a casual conversation with the other. Such conversations typically are characterized by superficial and lighthearted chatter about the weather, your destinations, or perhaps the reason you are traveling. If the conversation goes well, you might begin to sense the emergence of a rapport and mutual liking. When this happens, your expectations for what are appropriate and likely conversation topics begin to change. As the conversation drifts to more intimate topics, however, one or the other of you begins to disengage, and pretty soon you have both retreated into the safety of a book, magazine, or the passing scenery. What has happened? In all likelihood, at some point in the interaction your perceptions of the situation diverged, with one of you defining it as a conversation between intimates while the other still saw it as an interaction between relative strangers. A comment or action that would have been perfectly acceptable according to one perception was clearly unacceptable according to the other. If one party to an interaction perceives that he or she has crossed a threshold of intimacy while the other does not, the results can often be embarrassing. Thus the maintenance of a shared definition of the situation is as important as an accurate perception of the other person for maintaining mutual understanding and satisfactory interaction.

I Said-You Said: Actor-Observer Differences in Perception

Imagine that you have just bought a new car. The next day, while showing it to a friend, he asks you why you decided on this particular car. What would your answer sound like? In all likelihood your explanation would center on describing the characteristics of the car: its reliability, styling, roominess, gas mileage, cost, and so on. Although different people might stress different characteristics, most would nevertheless answer such a question by talking about the car. Now, suppose instead that your friend has just bought a new car and someone asks you your opinion about why he chose that particular vehicle. Your answer might be quite different. Rather than talking about the car, your reply would probably focus on your friend. “He’s having a midlife crisis, so he decided to buy a sports car.” “His wife just had another child, so they wanted something with lots of room.” “He has a long commute, so he wanted something really reliable.” In thinking about the causes of other people’s actions, we tend to attribute their behavior to their unique needs, desires, or personality characteristics. In thinking about or explaining our own behavior, however, our emphasis typically centers on external factors. This difference reflects a fundamental contrast in the way actors and observers are oriented to the world. As actors, we are constantly having to adjust our actions to accommodate other people and the situations in which we find ourselves. As a result, when we think about why we have behaved in one way or another, we are inclined to focus on the situational or environmental conditions that influenced us, but as observers we tend to focus on whatever the actor is doing. This difference in focus leads us to attribute their actions to their own preferences or personal characteristics. It is not hard to see how actor-observer differences can lead to serious misunderstandings. Unless we force ourselves through conscious effort to mentally put ourselves in the position of the other and at least imagine how that person perceives the situation, we are unlikely to appreciate the external factors that influence his or her behavior.

Try to See Things My Way: Perceiving through the Eyes of the Other

Obviously, our ability to understand each other would be significantly enhanced if we could somehow temporarily switch positions with each other—if we could, as the old saying goes, walk a mile in each other’s shoes. Although the 1988 movie Trading Places, starring Dan Ackroyd and Eddie Murphy, exploited this theme with considerable comedic success, it also showed quite dramatically just how different life can appear from the vantage point of another. Although such literal trading of places may be restricted to the world of fiction, we do have the ability to at least imagine how things must look from the perspective of the other, and as I have already indicated, our ability to achieve mutual understanding and satisfactory interaction depends largely on our ability to do just that.

Social psychologists use the term role-taking to describe this process. According to pioneering social psychologist George H. Mead (1934), role-taking involves mentally placing ourselves in the position of the other in order to see the world, including ourselves, from that person’s perspective. Successful role-taking is necessary in order to formulate our own actions in a way that will be meaningful and acceptable to others. After carefully studying the development of role-taking abilities among adolescents, John Flavell (1968) suggested that it is an elaborate process requiring five interrelated steps. First, the individual must recognize the existence of other perspectives—that what we perceive, think, or feel in any given situation is not necessarily what others perceive, think, or feel. Although most people develop this understanding fairly early, it is amazing how often adults seem to forget it and assume that everyone else shares their view. Second, the individual must realize that taking the other’s perspective would be useful in achieving a particular goal. One of the primary determinants of whether or not we perceive such a need is the extent to which the attainment of our goals depends on the cooperation of others. It is quite simply less necessary for one in a position of power to take into consideration the views of subordinates than for subordinates to understand the perspectives of those in positions of authority. Overt reminders of the value of role-taking, in some cases, may be sufficient to trigger such activity. Recognizing the need to take the role of the other, however, does not guarantee that the individual has the ability to effectively do so. Third, the person must be able to successfully carry out a role-taking analysis, which Flavell calls “prediction.” In general, the ability to predict another person’s reaction tends to improve as a result of maturation and repeated exposure to a diversity of others. Fourth, it is necessary to maintain a fix on the other person’s perspective, especially if it contradicts one’s own view of things. This step, which Flavell calls “maintenance,” is especially difficult to accomplish if the perspective of the other is radically different from one’s own. Whenever people say, “I can see your point, but . . . ,” they are probably having difficulty with maintenance. Finally, role-taking is of little use if we cannot apply the insights gained from it to the situation at hand. Thus Flavell’s final stage—the application stage—is where we again assume the role of actor in formulating a response to the actions of the other.

The first four stages in this process (existence, need, prediction, and maintenance) are necessary in order to understand the actions of the other from that person’s perspective, and the final stage (application) is necessary if our response is to be accurately understood by the other. As a result of failures in role-taking, conflicts sometimes reach the point where both parties have acted in ways the other considers rude, inappropriate, or insensitive. Overcoming such impasses can be facilitated by forcing each party to view the situation from the point of view of the other. Perhaps the easiest way to accomplish this from within the situation is to calmly ask the person with whom you are in conflict to explain how he or she thinks it all got started, explaining that you want to try to see it from his or her perspective. Listen carefully to what the person says and, when he or she is finished, offer to explain how you perceived things. If both are willing not only to listen, but also to empathize with the other, the chances of reconciliation will be greatly enhanced.

Conclusion: Why Looking Is Not Necessarily Seeing

This chapter has focused primarily on the problematic nature of human, especially social, perception. Due to certain limitations that we have as biological beings, it is impossible to truly observe all that our immediate environment makes available to us at any given moment. Thus perception is highly selective. We are less likely to see what we don’t expect to see because we are not looking for it. Some unexpected events are sufficiently dramatic to force their way into our span of attention, but many of the more subtle aspects of human action will be missed to the extent that we do not expect them. Moreover, our expectations are often influenced by such biasing factors as cultural stereotypes and personal experiences that, although very salient to us, are not at all typical or consistent with the experiences of others.

Americans place a great value on personal experience. As a teacher of criminology, I am frequently confronted by students whose real-world experiences seem to be contradicted by the results of research findings I present in class. When confronted with such contradictions, the inclination of many people is to deny the validity of the research in favor of their own experience. Such an attitude, while understandable, misses two important points. First, it assumes that their experiences are typical, that the experiences of other people in other places are the same as their own. This assumption is often easily refuted by simply bringing other people into the conversation. The police officer, for example, who says, based on his experience, that intervention in domestic abuse cases has no effect on offenders is likely to be challenged by another police officer who cites cases of her own that do show an effect. The more we learn about the experiences of others who are different from ourselves, the less we are inclined to assume that our experiences and perceptions are shared by everyone else.

The second and somewhat more subtle point is that we often fail to recognize that we are participants in the world we observe, and as such we influence events in ways we might not realize. For example, research on police confrontations with juveniles reveals that the probability of an arrest taking place depends in part on the demeanor displayed by juveniles in their interactions with officers. Holding other factors constant, kids who react to questioning by the police with what the officers consider the proper respect are less likely to be arrested. What the arresting officers fail to realize in some cases is that the youths’ demeanor is influenced by the way in which they are approached by the police and by the experiences they have had with other police officers. Thus officers who expect certain youths to be confrontational might be inclined to display an overtly tough posture in order to seize initial control of the situation. With some juveniles, this approach serves to create the very problem it is intended to circumvent. In short, we are usually not passive observers of the world; we are participant observers, and thus we play an active role in creating the events we observe.

Our perception of events is affected not only by the expectations we have of the people involved, but also by our expectations of what actions are typical and thus should occur in particular situations. Our definition of the situation will influence what we expect to occur and will thus direct our attention toward those types of events and away from others. Expecting the glass to be half full leads us to focus on the water; expecting it to be half empty leads us to focus on the space above the water.

Another limitation on our ability to perceive events in their full complexity is that we can only see things from our own unique physical and social vantage point. For example, observers are naturally inclined to focus on the actions of the actor, whereas actors are inclined to focus their attention on those forces in the immediate environment to which they must respond and which they must take into account in formulating their actions. Moreover, inasmuch as normal interaction involves our continually switching back and forth between the role of observer and that of actor, we must pay close attention to the actions of the other in order to act in ways that are situationally appropriate. This makes it even more difficult for us to take the time to imagine how the interaction must appear to the other. Unfortunately, effective interaction requires that we do so. Developing our skills as role-takers is one of the few means at our disposal for counteracting the selective and often biased view we have of our interactions with others. If there is one skill that is likely to enhance our success as interactants, it is the ability to successfully see the world from the perspective of the other. Therefore, this chapter concludes with a role-taking exercise.

ROLE-TAKING EXERCISE

The next time you find yourself unable to understand the behavior of another person, try working through the following steps in the role-taking process.

1. Existence Does the other person have a different definition of the situation from mine? (The answer is very likely to be “yes” if the two of you occupy different social positions, especially if one of you has more power than the other—for example, in an employer-employee relationship.)

2. Need Would I benefit from being able to see the situation as the other sees it? If so, how?

3. Prediction Try to imagine that you are the other; imagine the pressures (social, emotional, financial, etc) and influences that might affect that person’s viewpoint Imagine how you might act under those same pressures and influences.

4. Maintenance If you have been successful so far, you should have a bit more understanding of the other’s behavior. At this point, however, the tendency is to think, “OK, maybe I can see why he acted that way, but that is no excuse.” If so, you are slipping out of the role of the other and back into your own view. Remember, you are not trying to find excuses for the other, you are just trying to understand him or her, for your own benefit.

5. Application If you truly understand the other better, how can you use that understanding to repair the damage that has been done and avoid such misunderstandings in the future?

Hint: If you decide to share with the other your new found understanding of his or her behavior, be careful to avoid sounding condescending. Remember, actions speak louder than words.