Modest Actions, Monumental Misunderstandings1

Great literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.

EZRA POUND, American poet

That which makes great literature often makes unfortunate discourse. During a speech to the American Enterprise Institute on December 5, 1996, Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan posed the following questions: “How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become the subject of unexpected and prolonged contractions, as they have in Japan over the past decade? And how do we factor that assessment into monetary policy?”

In the fascinating psychological world of the stock market, the mere suggestion by someone of Greenspan’s economic power that the market might be due for a fall can produce a familiar self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby stockholders attempting to sell before their current holdings became devalued produce that very devaluation. As a result, those somewhat slower on the draw suffer the consequences. No doubt stockbrokers, who stand to gain whether stocks are bought or sold, do little to quell such fears. Whether Greenspan anticipated the far-reaching effect of his comments is unknown, but it is unlikely that even he imagined just what a dramatic and immediate impact his words would have. It is often the unfortunate plight of those in positions of authority that casual comments are accorded significance well beyond their intentions, although it is also true that such individuals can occasionally exploit this fact to their advantage.

The problem of assessing the significance of action also produces the opposite effect; words and deeds that are intended to carry great significance are sometimes ignored or casually dismissed. Although this can happen to anyone, it is more often the dilemma of those of lesser status. All actions—verbal and nonverbal, serious and facetious—can be intended to carry messages of great significance or of very little import, and can likewise be interpreted at multiple levels. The result is that many misunderstandings occur because observers over- or underinterpret the actions of others (Young 1995a). In order to clarify what I mean by levels of action, it will first be necessary to explain, in a general sense, the kinds of things actions accomplish.

Meanings and Effects: What Actions Do

John is walking down the street when he recognizes Kathy from a distance and waves. Kathy hesitates, then tentatively returns the gesture as they continue on their respective paths. How do we make sense of this hesitant and less-than-enthusiastic response to such a common action? A number of plausible explanations could be offered, but the answer is likely to lie in the meaning Kathy attributed to the wave. Did John actually wave his arm, or was he simply raising his hand to block the sun? If he was waving, was he waving to Kathy or someone else? If he was waving to Kathy, did she recognize him, and if she did, did she fear that returning the gesture would lead to a lengthy conversation she had no time for? Suppose the two had had an unpleasant exchange the day before. Was the wave intended sarcastically, repentantly, or casually?

This particular interaction illustrates the fact that all actions can be interpreted at different levels of meaning. At the most basic level, actions can be interpreted and described in purely physical terms. The action of hailing a cab, for example, could be described thus: “I stepped forward, placing my right foot on the street, leaving the left on the sidewalk, looked directly at the oncoming cab, raised both hands above my head, lowered them approximately forty-five degrees, and repeated this motion rapidly three times.” Actions that are interpreted in purely physical terms are likely to elicit quite different responses from those interpreted at a more social level. Cab drivers who observe this kind of gesturing but do not interpret such actions as they are intended will leave would-be passengers frustrated and stranded. Likewise, if I see a student raise her hand in class but interpret it as a purely physical action, such as stretching, I will not acknowledge the student as someone who has something to say. Actions interpreted as purely physical acts are not perceived as attempts to communicate social messages; thus we are inclined to pay them little attention.

In contrast, what I will call “generalized actions” are those that are seen as attempts to communicate something specific. The problem with generalized actions, however, is that the observer is unsure of precisely what they are supposed to mean. Suppose that during an office meeting Frank notices Jim look at Beth and nod. Does this nod of the head signal that Jim agrees with the point the speaker just made, or does it signal the initiation of some strategic plan he and Beth have worked out in advance? Frank might be fairly certain that it signals something of social significance (that is, Jim is not simply falling asleep), but without more information and interpretation, he cannot be sure what it means. Likewise, simple utterances such as “yes” can signal agreement or simply indicate that the listener is paying attention. Because generalized actions are assumed to communicate something the observer cannot interpret, they tend to grab and hold our attention as we struggle to make sense of them.

The third level of action is the implicative level. Unlike ambiguous generalized actions, implicative actions are those to which we are able to attribute precise meaning. Often, more important than the meaning itself is the fact that implicative actions are assumed to indicate specific motives or states of mind on the part of actors. To say that John flirted with Kathy, for example, is to suggest that John’s actions were motivated by a desire to let Kathy know that he found her attractive. For actions to be interpreted at the implicative level, observers must do a fair amount of interpretation. Noticing that John blinked one of his eyes while looking at Kathy (a physical action) requires no interpretation. Concluding that this action constituted a wink (generalized action) requires some interpretive work. Concluding, on the basis of a wink, that John was flirting with Kathy involves even more interpretation. After all, a wink can also indicate, among other things, that the two share knowledge of which others are not aware. Whether observers interpret a wink as meaning one thing or another depends on other information available to them.

Analyzing all the information necessary to interpret an action at the implicative level is a complex cognitive process. However, because our culture supplies us with a large set of standardized scripts with which we can quickly compare individual actions, categorizing an action as having one implication or another is greatly simplified. The down side of such categorical interpretations, however, is that misunderstandings are likely to develop if actions deviate much from standard scripts. For example, if John were twenty-five years old and Kathy were sixty, most observers would interpret John’s wink as something other than a romantic gesture, since our cultural scripts for flirtatious winks do not readily accommodate the possibility of romantic relationships between twenty-five-year-old men and sixty-year-old women.

Once actions have been interpreted, they may have dramatic effects on observers or they may have little or no effect at all. Ordinary actions, such as saying hello to those we encounter, paying for things we have purchased at the grocery store, or performing routine tasks at work do little to alter the future of those to whom they are directed. Other times, however, actions can have profound effects on others. Saying hello to someone we have refused to speak to for years, paying for a major purchase to an individual who stands to make a considerable personal profit on the sale, or performing work tasks that can mean the difference between being promoted and being fired are all actions that are likely to have significant consequences for ourselves and/or others involved. Thus, I use the term consequential actions to represent the highest or most complex level of action. Consequential actions share all the characteristics of implicative actions. However, they are not defined solely by their meaning, but also by the effects they have on observers. Greetings are consequential if and only if they are interpreted as more than just routine, thereby making those who are greeted happy, honored, suspicious, or in some other way mentally or emotionally different from how they were before the greeting.

Actions of this sort can produce two types of consequences. Personal consequences are those that somehow affect the life of the observer but do not alter the relationship between the actor and the observer. If people we love pay us compliments, they are likely to make us feel good, but they are unlikely to alter our relationships with them. After all, we expect occasional compliments from those we love. Compliments from those we perceive as especially objective or critical, however, can make our day. In addition to such personal effects, actions often have interpersonal consequences; that is, they affect the relationship between the actor and the observer. Receiving a compliment from someone we don’t particularly like, for example, might increase our liking for them and thus influence our future relationship.

To summarize, all actions can be described and may be interpreted at a physical, generalized, implicative, or consequential level. As we move from the physical to the generalized, to the implicative, more information is necessary and additional interpretation is involved. Finally, consequential actions are distinguished from others by virtue of the significance of the effects they have on observers or the relationship between actors and observers.

Intentions, Interpretations, and the Creation of Misunderstandings

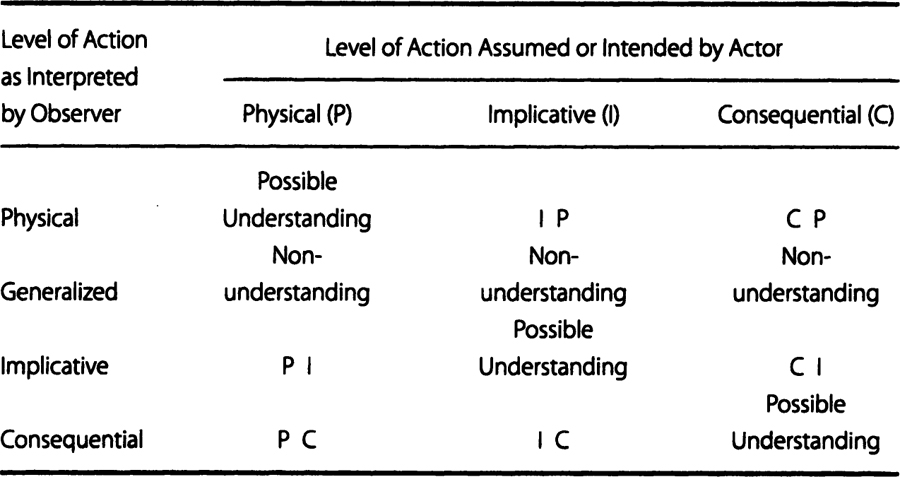

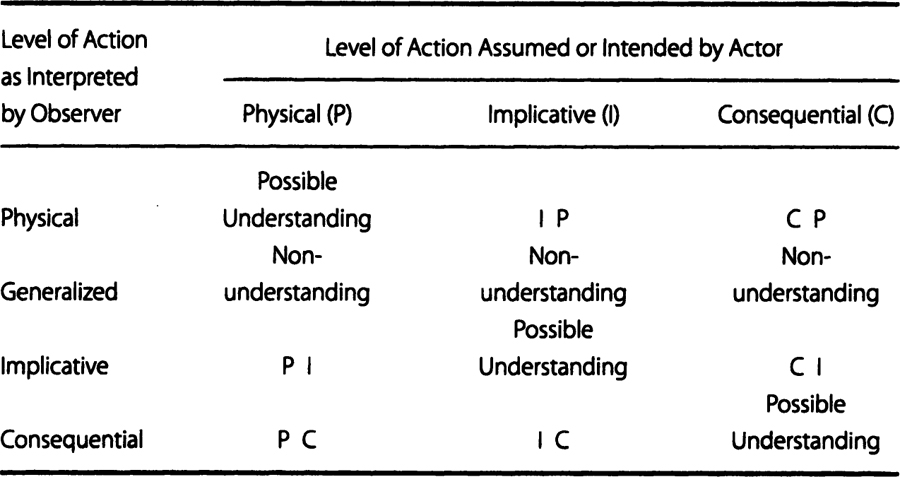

It is clear that actions intended at one level are sometimes interpreted at another level. Likewise, many misunderstandings are the result of the fact that actions intended at one level are interpreted at another. All the possible types of misunderstanding that can result from over- or underinterpretation are displayed in Table 1. As the table shows, observers might recognize any action on the part of actors in physical, generalized, implicative, or consequential terms. However, actors do not normally intend for their actions to be interpreted at a generalized level. Most physical actions are performed with little or no regard for the way others might interpret them. All social actions, however, are performed with the expectation that others will interpret them in a particular way. For example, I might move my head in a nodding fashion to relieve neck tension or place my hand in a waving position in order to block the sun, but I do not nod or wave at another person unless I intend it to have a particular meaning to someone. Thus, although actions may be interpreted at any of the four levels discussed above, actions are never intended at a generalized level. As a result, there is a certain asymmetry between the levels at which actions may be intended by actors and the levels at which they might be recognized by observers.

This asymmetry between levels of intention and levels of interpretation is reflected in Table 1. The cells of the table designated by two capital letters represent the types of misunderstandings that can result from the mismatch between actors’ intentions and observers’ interpretations. Before discussing these different types of misunderstanding, I should make a few other points. First, as discussed above, no actions are intended as generalized actions. Second, any actions interpreted as generalized actions result in nonunderstandings. This is because both understandings and misunderstandings—in contrast to nonunderstandings—imply that the action has a particular meaning for observers. Because generalized actions are completely ambiguous to observers, they cannot be misunderstood; they can only be not understood. Finally, although understanding can exist only when actions are interpreted at the same level at which they were intended, interpreting an act at the appropriate level does not guarantee that the act has been correctly understood. For example, if John’s flirtatious wink is correctly perceived as an implicative action, the observer might still be wrong about exactly what it implies. Thus, I have used the term possible understanding to describe situations in which intention and interpretation levels match.

Table 1. Intended Versus Recognized Level of Action

The cells in the table representing misunderstandings are identified with the first letters of the level of intention and the level of interpretation, respectively. The two misunderstanding cells in the upper right corner of the table (IP and CP) and the CI cell represent situations in which the actions of the actor have been underinterpreted, whereas the three cells in the lower left (PI, PC, and IC) are all the result of overinterpretations on the part of observers. For example, an IP misunderstanding would be one in which an actor intends the action to have specific social meaning, but the observer misinterprets the action as being purely physical. If a listener clears her throat to signal to the speaker to beware of what he says, but the speaker interprets the gesture as nothing more than an effort to cope with a congested throat, he has misunderstood the gesture by underinterpreting it. On the other hand, a PI misunderstanding would result if a speaker interpreted a purely physical clearing of the throat as a signal by the observer that the speaker should watch what he says. Likewise, an IC misunderstanding suggests that the observer has overinterpreted an action that was intended to imply something of relatively minor personal or interpersonal consequence to mean something more consequential. The following is an example of a PC misunderstanding.

The other night in class I hiccuped during a presentation being given by another girl in the class. You have to understand that my hiccups can sound very strange, sort of like a gasp. That would have been embarrassing enough, but it just so happened that I hiccuped right when she was giving her opinion on something kind of controversial, so she was probably feeling a little self-conscious about it anyhow. Well, it was clear from her reaction and the reaction of others that they thought my hiccup was a gasp expressing my disapproval or disagreement with what she said. That made me feel really embarrassed, so I was quick to apologize and assure her that it was just a hiccup.

As this story suggests, producing inadvertent bodily noises in public can be embarrassing enough on its own. What is also clear, however, is that the major source of embarrassment here was the fact that the physical act of hiccuping was interpreted as the social act of vocally disapproving, an act that would have had negative consequences for both the self-esteem of the speaker and the future relationship of the two individuals.

Because physical actions are usually easy to distinguish from social ones, they are less likely to be interpreted at another level. Distinguishing between levels of social action, however, is somewhat more difficult. Consider the following example of an IC misunderstanding, supplied by another student.

About two years ago, New Year’s Eve, a male friend and I had a terrible misunderstanding concerning our relationship that night First of all, I asked him if he wanted to go out. He said he had never been out on NYE before. I had not made any plans, so I thought it would be fun to go celebrate together. The night was a disaster. He assumed that we were on a date. We were not. I was only concerned about being a good friend. I did not want a serious relationship with him. Everything I did he took as a sign that I liked him. I was just being nice. I was treating him as I treated everyone else. I even told him point blank that I didn’t like him in that way. To this day, I don’t know how to act around him. If I’m nice, I feel he thinks I like him [romantically], and if I’m mean, I feel like he thinks I’m weird. Needless to say, we are not the friends we used to be.

In this example, the act of asking an opposite-sex friend to go out on New Year’s Eve was not expected to have significant interpersonal consequences. The narrator was simply suggesting that since neither had plans, maybe they should celebrate the new year together. Unfortunately, her friend interpreted the invitation as an act that had significant consequences for their relationship. Ironically, because of the misunderstanding, the evening did have lasting consequences for their relationship, but not of the kind initially imagined by the friend.

Am I Paranoid or Just Powerless? Overinterpreting and Underinterpreting Actions

There are many specific reasons why a particular action might be over- or underinterpreted. In a general sense, however, there are two types of causes: personal and interpersonal. By personal causes, I mean that some individuals are more inclined than others to have difficulty finding the appropriate level of interpretation. People who suffer from paranoia, for example, have a persistent tendency to overinterpret the actions of others. Believing that the actions of others have serious personal consequences for oneself is a major part of paranoia. This is not to say that anyone who has a tendency to overinterpret the actions of others is paranoid. Often there are understandable interpersonal reasons for such interpretations. As Charles Berger (1979) suggests, individuals who are highly dependent on others are likely to attach great significance to the actions of those upon whom they are dependent, and justifiably so. Young children, for example, often act as though dire consequences would ensue if their parents left them alone, even momentarily. Although adults often laugh at such reactions, from the point of view of the dependent child, who does not know when the parents will return or what might happen while they are gone, such concerns are not unreasonable. Dependent or insecure adults may react similarly to the idea of their partner leaving them to spend time with others, regardless of how legitimate the reason. Dependence is often linked to powerlessness, and the actions of powerful individuals really do tend to have more significant consequences than those of the less powerful individuals. For example, although most of the actions of patients have relatively minor consequences for the physicians upon whom they depend, the actions of the doctors can have life-or-death consequences for their patients.

As a result of the greater consequentiality of the acts of the more powerful interactant, situations that involve interactions between subordinates and those with power over them tend to motivate the less powerful individuals to closely monitor their own actions and those of the other. Such monitoring is motivated by the desire to avoid being misunderstood and the parallel need to understand the full implications of the other’s actions. Situations that tend to produce these kinds of misunderstandings are found in the lower left corner of Table 1. In contrast, situations that are less personally consequential for the observer will be more likely to produce underinterpretations and lead to the type of misunderstandings found in the other cells of the table.

Actors and observers don’t always devote the same measure of attention to an interaction. As a result, as actors we do not always consciously think about our intentions before we act. Before we sigh, yawn, or stretch, for example, we are not likely to think about how such physical acts will be interpreted by others. However, upon realizing that our actions have been misinterpreted, we become acutely aware of what impressions we did not intend to give. Thus, whether or not we consciously intended an action to carry a particular level of meaning, we are quick to declare that certain meanings were not our intention.

In general, the diligence with which we monitor actions, both our own and those of others, is related to the importance of the interaction for us. As I suggested in the previous section, in situations that we expect to be highly consequential, we tend to be especially attentive to the more subtle aspects of the other’s behavior and are thus more sensitive to the implications of all his or her actions. On such occasions we also tend to be more careful in orchestrating our own acts, choosing our words carefully, and plotting our moves more methodically than usual. Because of this enhanced attention to detail and subtlety, we are more likely than our less invested interaction partner to recognize misunderstandings when they do occur.

Whether a misunderstanding is first recognized by an actor or an observer has important implications for the future of the interaction. Observers who realize they have misunderstood the actions of another can simply adjust their thinking to bring it into line with newly discovered information. When actors are the first to recognize that they have been misunderstood, however, they must take concrete action in order to rectify the situation, and sometimes this can be a traumatic realization. As the work of psychologist Arnold Buss (1980) suggests, the realization that we must actively work to correct a misunderstanding is likely to produce a degree of anxiety. In order to take corrective actions, we often must disrupt the flow of interaction and take it in a new and probably uncomfortable direction. This alone can make us somewhat uneasy, but such uneasiness will be exaggerated by any uncertainty we might have over whether or not the action we are contemplating will be considered appropriate. This is one of the reasons why realizing that we have been misunderstood is normally more bothersome than realizing that we have misunderstood someone else. In the face of such a dilemma, whether or not we take any action at all depends largely on whether the anxiety of allowing the other’s misunderstanding of our actions to persist is greater or less than the anxiety created by imagining the other’s reaction to our efforts to clarify the situation.

Conclusion: Truth and Consequences

Actions can be intended as physical, implicative, or consequential and can be interpreted as either physical, generalized, implicative, or consequential. When words or deeds are intended at one level but are interpreted at another—that is, when we read too much or too little into each other’s actions, misunderstanding results. Casual or innocent comments that are overinterpreted can result in such interpersonal problems as embarrassment, resentment, or outright conflict. Although discovering that their actions have been underinterpreted is likely to be somewhat less problematic at the interpersonal level, this kind of misunderstanding nevertheless can be extremely frustrating for actors who might be left wondering just how obvious they have to be to get their point across.

Whether we recognize such discrepancies between our intentions and others’ interpretations depends largely on how closely we monitor the situation, and that often depends on how much we have to gain or lose from the interaction. In general, interactions among those with different amounts of social power are more consequential for less powerful individuals. As a result, they will typically monitor their own actions and those of the other more carefully, and, thus, will be more likely than the other to recognize when they have been misunderstood. Although such a realization is beneficial in that it allows them the opportunity to clarify things, it may, for that very reason, create extreme anxiety. After all, actions aimed at clarification could also be misunderstood, thus making bad matters worse. Moreover, if actors are wrong in their perception that they have been misunderstood, clarification efforts will be inappropriate, which in turn might make the other feel insulted or make the actor appear foolish. Thus, while problematic for anyone, the perception of having been misunderstood can be especially traumatic for those of a subordinate status.

A common way of alleviating some of the anxiety associated with face-to-face interaction is to provide feedback to the other. Feedback allows actors to assess whether or not they are being understood. We have all had the unpleasant and somewhat intimidating experience of interacting with the type of person who provides little or no feedback as we struggle to express ourselves. When conversing with anyone, but especially those of lower status, we should be aware of the need to occasionally reassure them that we understand what they are communicating. However, it is wise to be aware of how we express our understanding. A common way of doing so is by nodding and using such verbal affirmative responses as “yes” or “O.K.” Unfortunately, such responses can be interpreted as signs of agreement rather than interest or understanding. More explicit responses, such as “I understand” or “I see what you mean,” are less likely to be misunderstood. As we will see in the final chapter, this seemingly minor distinction can be especially important in interactions between men and women. Likewise, we should be willing to politely ask for clarifications when necessary. Avoiding misunderstandings is often easier and almost always less stressful than attempting to correct them. This assumes, of course, that we want to reduce the stress of those with whom we interact.

Note

1. For a more elaborate and scholarly treatment of this topic, see Young (1995a).