temples of the grail

In the land of Salvation, in the forest of Salvation, lies a solitary mountain called Muntsalvach, which King Titurel surrounded by a wall, and on which he built a costly castle to serve as the Temple of the Grail; because the Grail in that time had no fixed place, but floated, invisible, in the air.

…

Albrecht von Scharfenburg, Der Jüngere Titurel

The Quest

The way to the Grail lies within: this much is made clear throughout the stories of the quest and in its imagery of the divine search for what is best in humanity. In this scenario the body, which has always been recognized mystically as an impediment to the realization of spiritual freedom, becomes a testing ground where the good and bad aspects of the individual do battle, the one seeking to know the Divine and the other running from it. The temple, of which the body is an image, performs a similar function, in the Grail story especially so, reflecting the duality at the heart of all matter and the desire of humanity to conquer its divided self by stretching up to meet the descending love of creation.

We see this immediately in the Arthurian Grail Quest. Arthur is prevented from entering the inner sanctum in Perlesvaus, and when Sir Lancelot in Le Morte d’Arthur comes at last, after many adventures, to the Chapel of the Grail, an unearthly voice warns him not to enter. Hesitating outside the door, he looks within and sees

a table of silver, and the Holy Vessel, covered with red samite, and many angels about it…and before the Holy Vessel…a good man clothed as a priest. And it seemed he was at the sacring of the mass.113

Watching the events that follow, Lancelot sees, just as Arthur does, the celebrant holding aloft the image of a wounded man, as though he would make an offering at the altar. When it seems as though the aged priest would fall from the effort, Lancelot enters the chamber out of a pure desire to help. At once, however, he is struck down by a breath of fire and blinded by the light that flows from the Grail. Being blinded by his love for Arthur’s queen, Lancelot does not know the way into the presence of the sacred things.

The way that all the quest knights—and all seekers like them—must follow is a hard one, for it consists of entering the temple, which is so designed that it serves as an initiation test for all who wish to share in the mysteries. It thus reflects the purpose of the Solomonic Temple within whose depths the seeker was tested in the Holy of Holies. Lancelot’s experience is echoed by many who set out unprepared for such tests and who end by being blinded by what they cannot understand. However, the way towards the home of the Grail can offer a means of knowing, of understanding the light. Many temples have fallen in ruins, but the true temple is never destroyed.

The earliest traditions relating to temple building depict them as liminal spaces, as dwelling places for the gods, where they may enter their house and communicate with their creation. The earth upon which the temple stands is thereby sacred earth, either through its being placed at a particular spot or by a hallowing touch of the Divine that marks out the building as a source for those in search of a sacred experience. Thus it becomes a temenos, a place set apart, where signs visible only to those who have followed the path of enlightenment tell us that here is sacred space, which to enter means to enter the sphere of the Divine—the reflection of the heavenly on earth.

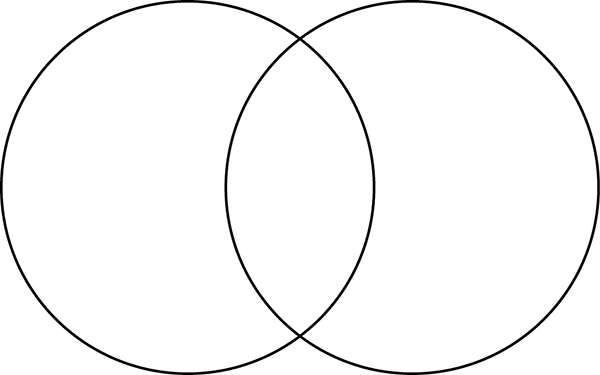

For this reason the forms most often incorporated into the design of the temple are those of the circle and the square—symbolic representations of heaven and earth—so that many consist of squared stones set up in circles (the megalithic temples) or rectangular buildings supported by rounded pillars (Egyptian, Hellenic, and Hebrew temples). These can also be seen as archetypal images of the masculine and feminine, so that the circle of the heavens and the square of earth unite in a single image.

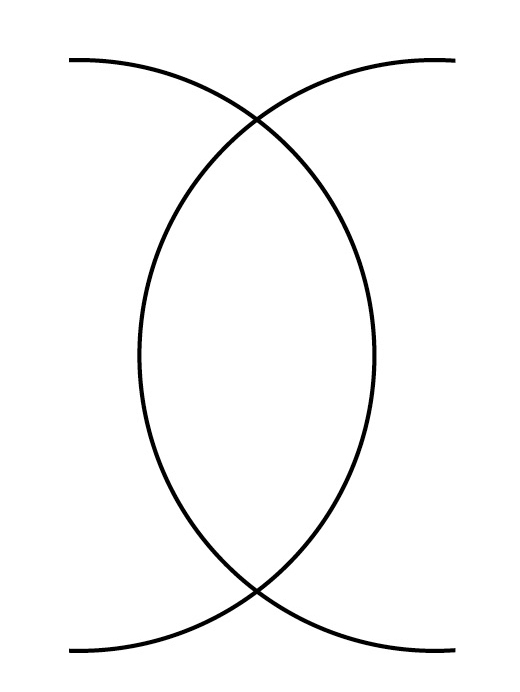

This may be expressed graphically by a symbol known as the vesica piscis, two overlapping circles (figure 3) that illustrate the link between creator and creation that takes place in the temple, whether directly or through the agency of priests and seers. Plotinus understood this perfectly when he wrote (using a slightly different analogy) that the human is drawn to the divine “like two concentric circles: they are only one when they coincide and only two when they are separated.”114

It is a state of spiritual separation that causes the failure of Lancelot and those like him who seek the Grail for their various and diverse reasons, and it is for this reason that the Grail Temple exists: to show the way back to a state of unity within the divine impulse of creation.

It is for this reason also that we first read of the appearance of the Grail as an aftermath to the story of the Fall. It is said that the Grail was entrusted to Adam at the beginning of time, but that after the Fall it remained behind since it was too holy an object to be taken into the world. But there is a tradition that says Seth, a child of Adam and Eve whom the Gnostics revered as a hidden master, made the journey back to the gate of Eden in search of the sacred vessel. He was permitted to enter and remained for forty days, at the end of which the Grail was given into his keeping, to serve both as a reminder of what had been lost and as a sign of hope and redemption to come, though this remained unrecognized until the time of Christ, when the symbol of the Grail as Chalice became established in Christian belief.

What is most especially important here, as the Vulgate Cycle says, is that “those who possessed the Grail after (Seth)…were by this very fact, able to establish a Spiritual center destined to replace the lost Paradise, and to serve as an image of it.”115 It is this image that is represented by the Temple of the Grail, as a place where creator and created can meet and converse as once they had in Paradise.

In this way the temple can be seen to represent a cosmic evolutionary diagram. It is as though the temple builders, by inviting the Divine Presence to descend into the temenos, were asking not only to be guided along the path towards the unity of perfection, but also anticipating that God or the gods would evolve through contact with them. They seemed to be saying that while the gods and spirit and humanity matter—and the latter two cannot evolve separately—they are linked like two interlocking circles, which are only complete when superimposed precisely, one upon the other. Thus all temples and churches were intended as physical glyphs to be read by both humankind and their gods, as a mirror reflecting images of the temporal and divine upon each other.

As we shall see more fully in chapter 6, this imagery is continued in the iconography of the Virgin Mary, who becomes a human temple and a vessel for the Divine, and whose reply to the angel of the Annunciation in the painted imagery of the iconographers is represented in reversed mirror writing. This is done so that her words may be read by the angelic power above her, while Mary herself is sometimes referred to as “a mirror of the greatness of God.”

Thus in the earliest temples of which we know, the stones, which gave megalithic man his name, were erected in circles, set up on power points in the earth so that they served as living extensions of the earth herself—the mother holding out her arms towards the moon, the sun, and the stars. These huge astrological observatories were built as much for the gods as for humankind—not just to honor them but also to invite them to participate in the ritual living of life in and around them. Or to quote Plotinus again:

Those ancient sages who sought to secure the presence of divine beings by the erection of shrines…showed insight into the nature of the All (perceiving that) though the Soul is everywhere its presence will be secured all the more readily when an appropriate receptacle is elaborated serving like a mirror to catch an image of it.116

In its most complex yet complete form, this cosmic mirror for the reflection of god or gods becomes also an initiator into the divine mystery of creation: the most perfect object of the quest. As such it may be expressed by the eternally fixed but changing pattern of the maze, and it is no accident that the architects of the Gothic cathedrals such as Chartres, in an endeavor to encode the mystery of the temple into the design of the great medieval churches of Europe, chose to include this form so often on both floors and walls.117

The Temple of the Grail was a logical outcome of this, and it is not surprising to find how closely it conforms throughout its many representations of the traditional archetype.

The Shape of the Temple

The imagery of the Grail Temple is consistent. It is usually at the top of a mountain, which is in turn surrounded either by an impenetrable forest or by deep water. Access, if any, is by way of a perilously narrow, sharply edged bridge, which became known as the Sword Bridge. To make entrance even harder, the whole temple or the castle that contained it would often revolve rapidly, making it almost impossible to gain entry by normal means. Once within, more perils awaited, and for those few who succeeded in reaching the center, where lay the Chapel of the Grail, the experience could, as in Lancelot’s case, be both chastening and parlous. Nor was the castle without its human guardians; at an early stage in the mythos a family of kings, supported by a specially chosen body of knights, appeared to serve and protect the sacred vessel. It is from this tradition that the association with the Templars emerged.

The most completely developed description of the medieval Grail Temple is to be found in the Middle High German poem Der Jüngere Titurel (circa 1270) attributed to Albrecht von Scharffenberg.118 Here the lineage of the Grail Kings is traced back to Solomon—a detail that, as we shall see, is of some importance—but the setting is firmly medieval in its details. According to Albrecht, Titurel, the grandfather of the famous Grail knight Parsifal, was fifty when an angel appeared to him and announced that the rest of his life was to be dedicated to the service of the sacred vessel. Accordingly, he was led into a wild forest from which arose the Mountain of Salvation, Muntsalvasche, where he found workers gathered from all over the world who were to help him to build a castle and temple for the Grail—which at that time floated houseless in the air above the site, supported by heavenly hands.

So Titurel set to work and leveled the top of the mountain, which he found to be of onyx and which, when polished, “shone like the moon.” Soon after he found the ground plan of the building mysteriously engraved on this fabulous surface.

The completion of the temple took some thirty years, during which time the Grail provided not only the substance from which it was built, but also food to sustain the workmen. Already the Grail is seen as a provider—a function it continues to perform. But more rarely, and importantly for our argument, it is here seen as contributing directly in the construction of its own temple, making one a part of the other, the design nonhuman in origin and the execution only attributed to the hands of man.

At this point in the poem Albrecht devotes one hundred and twelve lines to a description of the temple so specific in detail as to leave one in little doubt that he is describing a real building.119

The temple is high and circular, surmounted by a great cupola. Around this are twenty-two chapels arranged in the form of an octagon; and over every pair of these is an octagonal bell-tower surmounted by a cross of white crystal and an eagle of gold. These towers encircle the main dome, which is fashioned from red gold and enameled in blue.

Three entrances lead inside: one in the North, one in the West, a third in the South from which flow three rivers. The interior is rich beyond compare, decorated with intricate carvings of trees and birds; while beneath a crystal floor swim artificial fish, propelled by hidden pipes of air fuelled by bellows and windmills. Within each of the chapels is an altar of sapphire, curtained with green samite, and all the windows are of beryl and crystal, decorated with other precious stones.

In the Dome itself a clockwork sun and moon move across a blue enameled sky in which stars are picked out in carbuncles. Beneath it, at the very center of the temple, is a model of the whole structure in miniature, set with the rarest jewels, and within this is kept the Grail, itself a microcosmic image of the whole universe of creation.120

It is clear that what is being described in Albrecht’s poem is a type of earthly paradise. Details such as the three rivers, as well as the overall layout of the building, frozen and perfect in its jeweled splendour, along with artificial birds and fishes, all support this conclusion. The first home of the Grail is being rebuilt in medieval terms, but it remains a copy, a simulacrum of the true temple whose reality it merely mirrors.

But the image described in the poem is not limited either to mythical or, indeed, literary manifestation. It is possible to trace the origin of Albrecht’s temple to an actual site, though this did not come to light until the 1930s, when the Orientalist Arthur Upham Pope led an expedition to the site of the ancient Sassanian (Persian) temple known as the Takht-i-Taqdis, or Throne of Arches, in what is now Iran. Attention had already been drawn by earlier scholars121 to the literary evidence suggesting a link between the semi-legendary Takht and the Grail Temple, but it was not until Pope published his findings that it became known that the reality of the Takht closely approximated the description of Albrecht’s thirteenth-century poem.

The site contained evidence of a great central dome surrounded by twenty-two side chapels (or arches) as well as other architectural details similar to those described in the Jungere Titurel. Even Albrecht’s mountain of onyx was accounted for by the presence of mineral deposits around the base of the site. These, when dried out by the sun, closely resembled the semiprecious stone.

Pope’s excavations also confirmed that the Takht had once contained a complete observatory, with golden astronomical tables that could be changed with the seasons. A star map was contained within the great dome, and to facilitate matters even further the entire structure was set on rollers above a hidden pit, where horses worked day and night to turn it through the four quarters, so that at every season it would be in correct alignment with the heavens. Literary evidence from Persian writings such as the Shahnameh122 further supported the details of the site and made clear the nature of the rites that had been celebrated there. These were of a seasonal and vegetational kind, and, when performed by the priestly rulers of ancient Persia, ensured the fertility of the land and the very continuation of its people’s life. Pope commented that the beauty and splendor of the Takht “would focus, it was felt, the sympathetic attention and participation of the heavenly powers”123—so that once again we have an expression of the desire for the direct entrance of the gods into a manmade temple—a temple which, furthermore, revolved—as did both the Grail Temple and, according to some versions, the walls of the earthly paradise—without which it cannot be said to be complete.

Solomon’s Temple

Many of the attributes discussed so far bring to mind an even more famous temple: that of Solomon in Jerusalem, the story of which is indissolubly linked with the history of the Knights Templar and with the history of the Ark of the Covenant, which is itself an image that shares many attributes with the Grail. It is also the story of a chosen race and their communications with God.

Built to house the Presence of God, the Solomonic Temple was the concretization of an idea that began with the revelation of Moses, who created the first tabernacle to contain the ark, and later extended it into the great image of the temple itself. From within this holy house God spoke “from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim that are upon the Ark of the Covenant.”124 But the tabernacle was never intended as a permanent home, and it was left to Solomon to complete the fashioning of a final resting place for the ark at Jerusalem.

Even this remained merely a pattern for the heavenly temple, the Throne of God, the temple not built by human hands: it possessed also a secondary spiritual life made from stones crystallized from the river Jobel that flowed out of Eden. There is a sense here of an image behind an image; while the link between the heavenly and earthly dimensions of the temple is part of the Edenic mystery, and therefore of the Grail, which in turn performs the same function as the ark as a place for the meeting and mingling of God’s essence with that of his creation.

This can be taken a step further by reference to Jewish Kabbalistic tradition, where the earthly temple is said to possess “two overlapping aspects: one heavenly and one divine.”125 Moses, who received the plan of the temple in much the same way as Titurel in Albrecht’s poem, is enabled to witness the mystery performed in the divine dimension, where the high priest is the Archangel Michael. Beyond this is a still higher and more secret sanctuary, where the “high priest” is the “divine light” itself.126

Recent evidence has come to light that seems likely, once it has been properly studied, to offer still further proof of the links between Jewish tradition and the Grail.127 In light of this we should not be surprised to learn that Chrétien de Troyes, who wrote the first proper Grail romance, may himself have been of Jewish origin, converting to Christianity before he composed his great poem.128

The mysteries of the Grail, which undergo a division into mind, heart, and spirit, echo the formation of the Solomonic sanctuary into the Temples of Earth and Heaven and the Temple of Light. In Jerusalem worshippers entering the outer court of the temple were said to have reached Eden; beyond this, in the Holy of Holies, the dwelling place of the ark or the Chapel of the Grail, are the mysteries of the heavenly world, where the concerns of mind and body are left behind and those of the sanctified heart begin. Of those who went in search of the Grail, few except Galahad went beyond this point, and those who did were assumed into heaven. It is as though, looking out of a window, the eye was led beyond a glimpse of the immediate world to gaze up into the heavens, and on looking was suddenly able to see beyond, through all the dark gulfs of space, to the Throne of God itself, there to be lost in light. Lancelot was struck down and blinded by that light, for which he was unprepared. Only his son, Galahad, was allowed to look directly into the heart of the Grail, but only at the direct invitation of God.

Of the several non-biblical accounts of the Solomonic Temple that exist, that of the Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun is one of the most interesting. In it he states that the vaults below the temple, which are still generally believed to have been the stables for Solomon’s horses, were nothing of the kind; they were built to form a vacuum between the earth and the building itself so that malign influences might not enter it from below.129

There is a suggestion of dualism in the opposing of the dark forces of the earth against those of the sky, and this is borne out by what we know of the construction of Greek and Roman temples, where the adytum stretching below the earth was of equal or perhaps greater importance to the building above ground, and which served as a meeting place for the subterranean gods and their worshippers.

By medieval times, when the original site of the Solomonic Temple had been demolished and rebuilt well before it became a Muslim shrine, the chamber mentioned by Ibn Khaldun had become known as a place of entrance and exit for the spirits of the dead, while of the original structure nothing now remained above ground. The Crusaders, however, continued to refer to it as the Templum Dominum (Temple of God), and it became sacred to the three major religions of the book. For the Jews it was the site of Solomon’s Altar of the Holocausts, the Holy of Holies, while to the Muslims it was the place from which the Prophet had ascended to heaven, so that for a time it rivaled Makkah (Mecca) and was attributed with the property of “hovering” above the earth. Thus the geographer Idrisi referred to it in 1154 as “the stone that rose and fell” (lapis lapsus exilians), which so closely recalls Wolfram von Eschenbach’s description of the Grail itself as lapis exilis (stone of exile), sometimes interpreted as “the stone which fell from heaven.”

It seems that here we have a paradigm for the whole history of the Grail and of the temple built to house it. The Grail, originating in paradise, can also be said to have “fallen” by being brought into this world by Seth. A late Gnostic account describes how it was, in fact, originally the sword of Lucifer but became impacted as he fell though space until, when he reached the earth, it had assumed the form of a cup.130 Through its use by Christ to perform the first Eucharist, it is hallowed and the world, like the lost Eden, redeemed so that it, too, “rises.” Equally, the stones used in the building of the temple and the design for its construction, as described by Albrecht, can be seen to have “fallen from heaven.”

The Solomonic Temple was to give rise to several imitations in the West, one of which at least concerns us in our examination of the temple of the Grail. It became common practice among the Crusader knights to chip off fragments of the rock upon which the temple had once stood. These they would take home as talismans of their visit to the Holy Land. One such man, a French knight named Arnoul the Elder, brought back one such piece to his home at Ardres in 1177, along with a fragment of the spear of Antioch and some of the manna of heaven (though how he obtained the latter is not related). According to the Latin Chronicle, Arnoul then proceeded to build a castle to house these holy relics.131

It was of curious design, containing rooms within rooms, winding staircases that led nowhere, “loggias” or cloisters (a feature of Chrétien’s Grail Castle), and “an oratory or chapel made like a Solomonic Temple.” According to Lambert, it was here that Arnoul laid to rest the objects he had brought with him, and it is interesting to note that these objects coincide precisely with the “hallows” of the Grail. The spear had long been identified with that which had pierced the side of Christ, and as such had become one of the features of the Grail Temple. Manna, the holy food of heaven, is the substance that the Grail provides, either physically or in spiritual form. The stone from Jerusalem was part of the “stone which rose and fell” and thus recalled the Grail stone described by Wolfram von Eschenbach. So here we have, assembled in a temple or castle constructed to resemble the Solomonic Temple, all the elements of the Grail hallows originating from the Holy Land.

Nor do the links with Solomon and his temple to the greater glory of God end here. Two important facts remain to be considered. The first concerns the Ark of the Covenant, which may be seen as the Grail of its age, and concerning a well-founded tradition the Ethiopian church maintains that it was removed from Jerusalem before the destruction of the temple by Menelik, a child of Solomon and Sheba. It is still kept in the cathedral at Aksum in modern day Ethiopia and has remained a central part of sacred practice within the Ethiopian Church. Known as the Tabot (from the Arabic tabut’al’ahdi, Ark of the Covenant), it is carried in procession at the festival of Epiphany, to the accompaniment of singing, dancing, and feasting, which recalls the time when “David and all the house of Israel brought up the Ark of the Lord with shouting and with the sound of the trumpet.”132 Replicas of the Tabot are kept in every church in Ethiopia, and where these are large enough to possess a Holy of Holies, this representation of the ark is kept within, as it was of old in the Temple of Solomon at Jerusalem.

Is it possible that we have here one of the contributing factors of the Grail story? It seems more than likely that stories concerning a quest for a sacred object undertaken by the fatherless son of a queen may well have reached the West, where they became the basis for another story of a fatherless child (Parzival) who goes upon such a quest.133 Add to this the nature of the ark itself, along with the fact that apart from the Kebra Nagast, in which this story is told in full, the only other known source is Arabic, suggests that the semi-mythical Flegetanis, to whom Wolfram attributed the ultimate source of his poem and who was also of Arabic origin, may have been the disseminator of this narrative.

Flegetanis/Wolfram speaks of the Grail as being brought to earth by a troop of angels where “a Christian progeny bred to a pure life had the duty of keeping it,”134 Similarly, the Kebra Nagast tells how Menelik, the child of Solomon and Sheba, brought the ark out of Israel to reside in a specially protected temenos in Ethiopia.

We have heard how Lancelot fared when he entered the chapel of the Grail to help the “man dressed like a priest” who was serving at the Mass. Even though his intention is good, he is not permitted to touch or to look upon the mystery. So, too, in the story of the ark’s journey from Gebaa described in the biblical book of Kings, when it had reached the threshing floor of Nachon, the oxen pulling the cart on which the ark rode began to kick and struggle and “tilted the Ark to one side; whereupon Oza put out his hand and caught hold of it. Rash deed of his, that provoked the divine anger; the Lord smote him, and he died there beside the Ark.”135

In Robert de Boron’s version of the Grail story, we find the story of Sarracynte, wife of Evelake of Sarras, whose mother had for a time shared the guardianship of the Grail in the shape of a host and kept it in a box, which is specifically described as an ark.136 She at least was allowed to touch it without harm, but such cases are rare in the mythos. Generally the mystery is too great to be looked upon or touched by one who is unprepared. For a woman to do so was even rarer. A visit to the Temple of the Grail must come first and its perils overcome before the revelation of the mystery can take place.

The Plan of the City

We have already noted that one of the most frequently occurring forms in temple design is that of the circle and the square. These designs may be seen, in part at least, to reflect a polarization of the masculine and feminine imagery that lies at the heart of the Grail mythos. This mystery is borne out by two seemingly unconnected elements: a design incorporated into the great cities of classical Rome and an adventure of Arthur’s nephew Gawain at the Grail Castle.

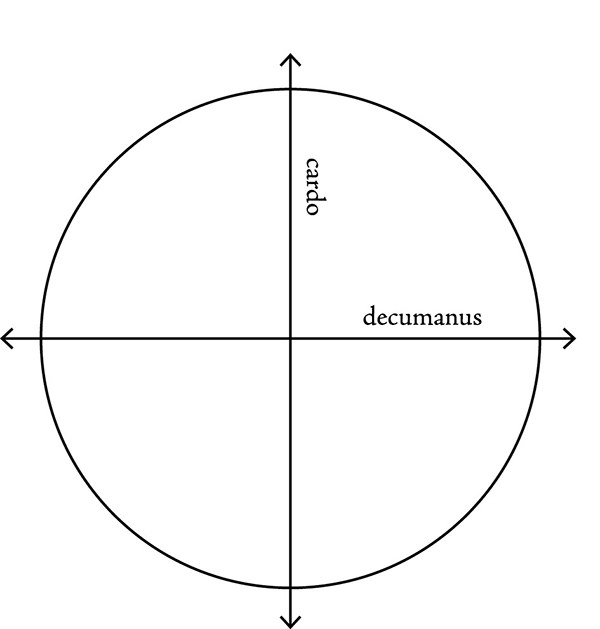

The plan upon which all Roman cities were based, like that of Titurel’s Grail Temple, was supposed to have been divinely inspired—revealed to Romulus, the city’s founder, in a dream. It really consists of two separate designs that together make up the total image of the city. These two designs incorporate the circle and the square; like the four square walls of the earthly paradise, Rome is built on the principle of the rectangle.

The urbs quadrata is divided across by the cardo and the decumanus. The cardo corresponds to the axile tree of the universe, around which the heavens revolve, and is therefore a type of the same artificial, astrologically inspired plan as that of the Takht-i-Taqdis and the Grail Temple. The decumanus (from decem, “ten”) forms the shape of an equal-armed cross when it intersects the cardo.

Within this complex were situated the temples dedicated to the sky gods, the masculine pantheon inherited from the Greeks, while adjacent to the urbs, or living quarters of the city, stood the citadel of the Palatine Hill, a circular form known as the mundus. This was the home of the dark gods of the underworld and of the older worship of the Earth Mother, who held the secrets of birth and death in her hands. In token of this, the center of the mundus contained a hole that went down into the earth, covered by a stone called the lapis manalis, which was only raised three times a year for the entrance and egress of dead souls, following the pattern established by the Solomonic builders and later followed by the Greeks.

Here the hidden place at the center is represented by an ancient form of Mother worship, existing within the place where male deities were honored. The representation is reflected by the physical organisation of the city in the forms of circle and square.

Another dimension of the Grail Temple, known as the Castle of Wonders, offers a different kind of adventure, that of Gawain and the magic chessboard. Gawain, a sun hero whose strength grows greater towards midday and subsides towards evening, enters the feminine realm of the circular castle, where he finds a square chessboard set out with pieces that move of their own accord at the will of either opponent. Gawain proceeds to play a game against an unseen adversary—and loses. Angrily, he tries to throw the board and the pieces out of the window of the castle into the moat, and it is at this moment that a woman rises from the water to prevent him. She is identified by her raiment, which is either red or black, spangled with stars, as an aspect of the Goddess, and after first rebuking Gawain for his anger and thoughtlessness, she becomes his ally and tutor, reappearing later in a different guise as his guide on the Grail Quest.137

It does not take much stretch of the imagination to see that here we have a restatement of the masculine and feminine elements associated with the temple. Gawain enters a circular (feminine) temenos and finds within it a square (masculine) chessboard, which is nonetheless checkered in black and white, a reconciliation of the previously opposing figures. When he tries to dispense with the board, he is prevented from so doing by an agent of the Goddess who, in subsequently helping him, teaches him the necessity of establishing a balance between the masculine and feminine sides of his nature.

This imagery is borne out by a further story from the Grail mythos that brings us back to the themes of both the Solomonic Temple and the Ark of the Covenant.

Solomon’s Ship

In Malory and elsewhere there are numerous references to the Ship of Solomon, the mysterious vessel that carries the quest knights or even the Grail itself to and from the everyday world into the timeless, dimensionless place of the sacred. However, it does more than this, being in some ways not unlike a kind of mystical time machine, programmed to bear the message of the Grail through the ages, from the time of Solomon to the time of Arthur.

It was built not by Solomon himself but by his wife, who is called Sibyl in the medieval Christian myth book known as The Golden Legend and may be identified with Bilquis, the Queen of Sheba.138 She, according to another Grail tradition, gave a vessel of gold to Solomon as a wedding gift—a cup that later became enshrined and supposedly resides to this day in the cathedral of Valencia as a type of Grail.139

According to the story related in La Queste del Saint Graal, certain objects were placed within the ship, which was then set adrift, unmanned, to sail through time as well as space to the era of the Grail Quest. These objects were Solomon’s Crown; the sword of King David; a great bed supposedly made from the Rood Tree; and three branches from the Edenic Tree of Knowledge, one of red, one of white, and one of green, which were arranged to form a triangle above the bed from which a canopy could be suspended.

We should not be surprised to find images of paradise contained in the Solomonic ship, for the vessel is clearly an image of the temple, this time afloat on the sea of time, its destination the country of the Grail. But perhaps the most important detail is that it contains wood from the tree that supposedly grew from a branch taken out of Eden by Adam and Eve and planted in the earth. From this tree, it was widely believed in the Middle Ages, the cross of the crucifixion was constructed, and part of it was used to make the Ark of the Covenant. The presence of this wood within the floating temple of Solomon’s ship makes for some fascinating speculation.

The ship, as has been said, was built at the behest of Solomon’s wife. It thus becomes doubly an expression of the feminine archetype, often regarded as a vessel and sometimes shown iconographically as an actual ship. It becomes an emblematic prototype of all the traditional imagery of the human vessel, the womb of the earth and the womb of woman; Mary as the living Grail who carries the Light of the World within her, and the blood which will, at length, be spilled into the cup, which will, in turn, become the Grail. Within this female temple are placed the images of kingship: sword and crown together with the three branches from the Tree of Knowledge, colored in red, white, and green, the colors of the alchemical process. Read in this way, the myth becomes clear: it can be seen as an expression of the masculine contained within the feminine—of the square within the circle, images of the Grail Temple in all its aspects.140

During the same account of the quest, the Grail knights voyage together for a brief time in the mysterious vessel. When the healing of the wounded king is achieved, the final act of Galahad and his companions is to carry the sacred vessel to Sarras, the Holy City that is itself an image of paradise on earth. They do so in the floating Temple of Solomon, and in token of his Christ-like role Galahad lies down on the great bed that had been made from the wood of the cross. Symbolically, he undergoes a species of crucifixion, and in doing so brings about the completion of the Grail work for that age.

After Galahad’s death, however, we may believe that the ship returned to these shores, bearing the Grail hither again, to await the coming of the next seeker and the time when it would be redeemed again, and to thereby help redeem the time in which this far-off event occurred—our own time, perhaps.

But the image of the temple as vessel, and of the Grail as a human vessel, brings us to the most fundamental aspect of the Grail Temple or indeed of the temple everywhere: the temple in man. This notion has been a common one since earliest times. In the Hindu Chandogya Upanishad it is held that

In the centre of the Castle of Brahma, our own body, there is a small shrine, in the form of a lotus flower, and within can be found a small space. We should find who dwells there and want to know him…for the whole universe is in him and he dwells within our heart.141

Or, as one might say, in the center of the Castle of the Grail, our own body, there is a shrine, and within it is to be found the Grail of the heart. We should indeed seek to know and understand that inhabitant. It is the fragment of the Divine contained within each one of us—like the sparks of unfallen creation, which the Gnostics saw entrapped within the flesh of the human envelope. This light shines within each one, and the true quest of the Grail consists in bringing that light to the surface, nourishing and feeding it until its radiance suffuses the world.

Chaque homme porte a jamais l’age du son temple—“each man is the same age as his own temple”—wrote the traditionalist philosopher Henri Corbin,142 adding that the completion of the temple on Muntsalvasche was a kind of second birth for Titurel, who, after this, we next see four hundred years older but perfectly preserved. The Temple of the Grail is really a divine clearing house for the souls of those who go in search of it—a kind of adjunct to paradise, with glass walls that reflect the true nature of the seeker (like the floor of Solomon’s Temple) and demand that he recognize himself.

The Temple of Man

The image of man is the image of the temple, as writers as disparate as Henry Corbin, Schwaller de Lubicz, Frederic Bligh Bond, and Keith Crichlow have all noted.143 Man must make himself into a temple in order to be inhabited by God. This is the object of all the tests—the Sword Bridge and the turning door, the Perilous Bed and the blinding light of the Grail. The concept begins with the Egypt of the pharaohs, if not earlier, in the caves of humankind’s first dwelling, and it continues through Platonic and Neoplatonic schools of thought. To them the temple was microcosmically an expression of the beauty and unity of creation, seen as a sphere. Expressed thus, it was reflected in the soul and became, indeed, “a bridge for the remembrance or contemplation of the wholeness of creation,”144 words that could be as well applied to the Grail or the divine enclave of which it is a part.

This is the origin of the Temple of Light (the haykat al-nur), the macrocosmic temple that lies at the heart of Islamic mysticism, of which the Sufi mystic Ibn al-Arabi says: “O ancient temple, there hath risen for you a light that gleams in our hearts”145—the commentary to which states “the gnostic’s heart, which contains the reality of the truth,” is the temple.

Here we are back in the world of the Solomonic Grail Temple, the images of which, transformed and altered, together with that of the earthly paradise, were enclosed in the world of the Arthurian Grail mythos. And that world becomes transformed in turn, back into the Edenic world of primal innocence, the original home of the sacred vessel, possession of which “represents the preservation of the primordial tradition in a particular spiritual center”146—the center, that is, of the heart.

Ibn al-Arabi wrote that the last true man would be born of the line of Seth, Adam and Eve’s lastborn son.147 Do we not have in this statement a clue to the destiny of the Grail bearer who will come among us at the time of the next “sacring” of the divine vessel? All the Grail knights were followers of Seth—who was the first to go in quest of it—and their adventures are transparent glyphs of the human endeavor to experience the Divine. Most of us, if we found our way into the temple unprepared, would probably suffer the fate of Lancelot. But the Grail Temple exists to show us that the way is worth attempting—that the center can be reached if we are only attentive enough to the message it holds for us.

But what happens when we do finally reach the center? If we look at what we have learned so far about the image of the temple on earth and in the heavens, we may begin to arrive at an answer.

Completing the Temple

All temples are incomplete. They can only be made whole by the direct participation of the creator, who must stretch down to meet and accept the rising prayers of their creation. So with the Grail; it too must be hallowed, made complete, as by the touch that makes blood of wine and flesh of bread. The Grail is made whole only when it is full, and it is not for nothing that the shape most often assumed by it is that of the chalice. If we see this as two triangles, one above the other, meeting at the apex point to form a nexus, we can see that it is an image of this divine meeting of upper and lower, temporal and divine (see figure 5).

The same event occurs within the sanctuary of the temple and is best expressed, as we saw earlier, by the figure of the vesica piscis, the two overlapping, interlocked circles that can represent God and humankind, and in the center of which, outside time or space, the opposites are joined; the male and female, dark and light imagery we have been examining and which are represented in the Grail story by the chessboard castle.

Also, we can see that in the human temple this is expressed by the need of each individual to reach upwards and be met halfway. We are all Grails to some degree, lesser or greater; but we are empty vessels until we offer ourselves to be filled by the light.

It is perhaps time that we looked finally at some of the imagery that has built up throughout this study. Indeed, there comes a point at which unsupported words can no longer make sense of the complexity of ideas presented. In the simple image with which we began, that of the vesica piscis, we have most of the story. The center of the design with the outer edges of the two circles taken away makes the shape of the Grail. Turned upon its side, it is still the same, except that now it represents the image of the Grail as temple, the building above, the adytum below, or as they may be seen, the God/Goddess with, between them, at the meeting point of time and place, the figure of humankind. And in the temenos between, the reconciliation of opposites, the perfection of sacred space, sained (made sacred) by the touch of the Divine, which interpenetrates the temporal at the point of human experience. So this experience can be shown as an exchange to which we can contribute equally with God; as was suggested earlier, the image of the temple is at once a glyph of creation and of the evolution of the gods.