Infection Protection When You Need a Urinary Catheter

Now that you've learned about the many actions you can take to prevent infections, are you ready to tackle the kinds of infections you might face as a hospital patient? Because urinary infections are the most common healthcare-associated infections, I'll start with them and then go on to prevention of other infections that affect many hospital patients. Here's the agenda for the next few chapters:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) associated with urinary catheters

- Respiratory infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)

- Surgical site infections (SSIs)

- Bloodstream infections associated with venous catheters (BSI)

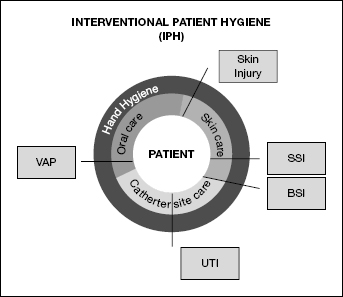

INTERVENTIONAL PATIENT HYGIENE

Because the healthcare-associated infection types listed above are so common, I co-developed with other health researchers a model for patient hygiene that assigns hygiene treatment for each common infection.1 Sounds simple, and is simple to follow, but as you have read already, healthcare workers for various reasons will not, cannot, or forget to follow simple hygiene procedures.

Start with the middle of the diagram on the next page which represents the patient—you! Then the next layer that surrounds (and protects) the patient are the three types of hygiene interventions you and your healthcare team must practice: oral care, skin care, and catheter site care. In other words, proper oral hygiene, skin bathing (remember those chlorhexidine wipes!) and keeping clean the area of your body at and around the catheter insertion point, are crucial to protecting that patient at the center of the model.

Components and outcomes of the IPH model.

The outer circle that surrounds the three types of patient hygiene is the most frequently performed hygiene procedure I have discussed time and again: hand hygiene! Healthcare workers must wash or sanitize their hands before performing any other hygiene treatment such as teeth cleaning, skin cleaning, or cleaning at the catheter site. If a healthcare worker does any of these procedures with unclean hands, then they are simply passing hand bacteria and viruses onto your newly cleaned skin, mouth, or catheter site.

Note the infections (VAP, BSI, UTI, SSI, and skin injury) in the boxes surrounding the circles. These are the infections that are kept away from the patient thanks to the protecting hygiene interventions noted in the shaded circle segments around the patient. For example, UTI (urinary tract infections) are kept away from the patient by performing proper catheter site care and hand hygiene. Surgical site infections (SSI) are kept away from the patient by proper skin care and hand hygiene. Blood stream infections (BSI) are kept away from the patient by performing proper skin care AND catheter site care, along with hand hygiene.

If healthcare workers practiced these simple hygiene interventions (oral, skin, and catheter site), you, the patient, will have a better chance of avoiding infections. Don't forget, you can be a part of that “protecting team” by reminding your healthcare workers to wash or sanitize their hands, and by ensuring your bathing routine is performed daily.

CAN'T GO WITH THE FLOW

OK, here's your first infection challenge. Whether you call it urinating, emptying your bladder, or voiding, it's something most people do several times a day without giving it much thought. But for people who are hospitalized, urinating may involve effort, discomfort, and sometimes the need for a urinary catheter.

What causes these problems? First, imagine trying to urinate while sitting on a hospital bedpan, as some hospital patients must do. If you've ever done it, you know how strange and uncomfortable it can be. Many people can't get urine to flow in that position. Next, your ability to urinate can be affected if you've had surgery or have a medical problem affecting your bladder, prostate or penis (in men), uterus or vagina (in women), or any organ in the area near your pelvic region. That's why you may notice thin tubing draining your urine into a plastic bag when you wake up after surgery.

WHAT'S HAPPENING DOWN THERE?

You can easily see the catheter tube leading outside of your body, but you may not understand where it's located inside your body and what it's doing there.2 Your kidneys are located over the bladder. That's where urine is formed. The kidneys filter waste and water out of your bloodstream. The urine then flows down from each kidney via thin tube-like structures called ureters (one on each side) and ends up in the balloon-shaped bladder.

The bladder stretches as it fills with urine. If everything is working right, urine won't continually drip out into the urethra tube below, thanks to a sphincter muscle that holds the bladder closed. But when the bladder is full, it's time for the nerves in the bladder wall to send signals through the spinal cord to the brain and back to the bladder. That starts contractions and relaxes the sphincter muscle, so urine can flow down the urethra and out of the body.

Uh, oh! What if you're not near a toilet or a bedpan? Fortunately, there's another sphincter muscle at the end of the urethra that you can control yourself to hold the urine in. You've probably done this many times.

WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

That's how urination works when there are no medical problems. But here's what can go wrong:

- In men, if the prostate gland just under the bladder gets too large, it presses on the urethra and can block urine flow.

- In men and women, blockages in the urethra can occur from tumors, infections, scar tissue, and other causes.

- Spinal cord injuries, strokes, tumors, diabetes, infections, and other conditions can affect the nerves that control the bladder. This may prevent transmission of signals to empty the bladder.

- Some medications, particularly cold and allergy drugs containing ephedrine, can cause difficulty in urinating so the bladder becomes painfully overfull and doesn't empty. That's called urinary retention.

When you're in the hospital, other problems may arise. For example, if you have urologic surgery or operations on nearby organs in the lower abdominal area (the uterus, for example, during a cesarean section), you're likely to develop urinary retention. After-effects of anesthesia also increase your retention risks, and so does being immobile in a hospital bed.

IN'S AND OUT'S OF CATHETER USE

With so many possible problems that can interfere with urination, you may not be surprised to learn that as many as one out of every four hospitalized patients in the United States winds up with a urinary catheter during a hospital stay.3

The most common type is a Foley catheter, also called an indwelling urinary catheter. It consists of a long, soft plastic or rubber tube that is inserted into the urinary opening (at the tip of the penis in men and just under the clitoris in women). The tube is then passed up through the urethra and into the bladder. Next, a tiny balloon at the top of the tube is inflated with sterile water through a second tube to hold the catheter in place. When it's time to remove the catheter, the balloon is deflated and the tube is gently pulled out.4

The bottom of the catheter tube is connected to a drainage bag, which collects the urine that flows down the tube. Because of gravity, the bag must be kept below the level of the bladder, to prevent urine from flowing back up.4

Q: Are there other types of catheters?

A: Several types of urinary catheters are available:

- Intermittent (short-term) catheters are used for quick drainage of urine. Because the catheter doesn't have to stay in place, there's no balloon at the top.

- People who have a blockage in the urethra may need a suprapubic catheter, which is inserted directly into the bladder through a small hole that's made in the lower abdomen.

- Another type called a condom catheter, used mostly for men who are permanently incontinent (can't control urine flow), doesn't involve a tube inserted through the penis. Instead, a condom-like covering with a tube attached is placed over the penis. Urine flows down through the tube into a drainage bag. This type of catheter is easy to change and poses less risk of causing an infection.4

Other types of catheters are used to deliver medications into the bloodstream (venous catheters), monitor heart function (cardiac catheters), and drain fluids from the abdomen or chest. We'll talk more about these in the following chapters.

Q: Does it hurt to have a urinary catheter?

A: Urinary catheters come in different diameters—choosing the best size for each person helps to prevent discomfort. Before it's inserted, the catheter tube is coated with lubricant to help it pass easily, but most people still feel discomfort during insertion. Men especially often feel pain as the catheter passes through the prostate area. A topical anesthetic applied to the insertion area may be used to decrease any pain for both men and women. However, once the catheter is properly inserted, it should cause only minor discomfort.5 If the catheter becomes painful, it needs to be replaced immediately.4

Catheters and Pain

When a urinary catheter is inserted properly, it should cause only slight discomfort.

Tell your doctor or nurse if it becomes painful. That means the catheter needs to be replaced immediately.

Q: Are there possible complications from having a catheter?

A: Some people develop allergic reactions to the latex used in catheter tubing and may need to switch to silicone tubing. Other possible complications include stones forming in the bladder, blood in the urine (hematuria), injury to the urethra, and, with long-term indwelling catheters, kidney damage. We also know that urinary catheters used in people older than 70 years are associated with an increased risk of death.6 But the most common complication of all is infection in the urinary tract or kidneys.4

HOW CATHETERS CAUSE URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Each year, about 2.5 million hospitalized patients in the United States develop healthcare-associated infections. One million of these infections (30 percent) are UTIs, the majority of which are related to the use of urinary catheters. Any device that's inserted into a part of the body is an open highway for germs to move right in. That's the major reason why catheter-related infections are so common.7

Q: What is the urinary tract?

A: The kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra are part of the urinary tract.

Q: Do all patients who have a urinary catheter get an infection?

A: No, but we do know that for each day you have a catheter in place, you have a 3–7 percent chance of bacteria getting into your urine. This is called bacteriuria. Do the math: If your catheter is in place for 10 days, you'll have a 30–70 percent chance of getting bacteriuria.7

Q: Is bacteriuria the same as infection?

A: No, but if the bacteria continue to multiply and start causing symptoms, such as pain during urination, then you have developed an infection. From 10 to 25 percent of people who get bacteriuria do develop UTIs. In addition, approximately 3 percent of people who have bacteriuria develop bacteremia, a potentially fatal condition in which bacteria growing in the urine get into the bloodstream, where they can travel throughout the body. Because of possible bacteremia, people who develop bacteriuria can have a three-fold increased risk of dying.8

Q: Are some catheters better than others in preventing bacteriuria?

A: Catheters that are coated with silver alloy have been shown to decrease bacteriuria. This is probably because silver acts like an antimicrobial agent—it kills bacteria. Because silver alloy catheters are more expensive than standard ones, some hospitals use them only for intensive care patients.

Q: “More expensive” shouldn't matter. Aren't hospitals responsible for doing everything possible to prevent infections?

A: Before January 2008, most hospitals and doctors worked on the premise that catheter-related infections were not always preventable and therefore not a top priority in terms of trying to decrease their numbers. In fact, some hospitals viewed them as a way to generate money from additional treatments and longer hospital stays.

That changed as of October 2008, when Medicare created guidelines for what they categorized as preventable hospital conditions. UTIs fit those guidelines and so do other healthcare-associated infections. This means that hospitals can no longer be reimbursed for any additional costs of treating UTIs that Medicare and Medicaid patients acquire in the hospital if those infections are considered preventable. Hospitals and healthcare workers always work to prevent infections in all of their patients, but now they have an even greater incentive.9

Good News!

Hospitals really don't want you to develop a UTI.

There's a big incentive for preventing it, because Medicare and Medicaid will no longer reimburse the hospital for the added costs of treating hospital-associated UTIs.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

The Medicare guidelines are good news for every patient, because healthcare workers work to reduce infection in everyone, not just those on Medicare/Medicaid. In addition, hospital physicians and administrators in the United States are fully informed about other infection control guidelines issued by the World Health Organization10 and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its associated professional infection control organizations.6,7 However, a recent survey of several hundred hospitals in the United States showed that the majority of hospitals weren't using even basic, proven practices to prevent hospital-associated UTIs.11 That means it's important for you to play a part in making sure you don't get an infection when you're a patient yourself or when you're acting as an advocate, helping to protect another person.

The Centers for Disease Control supports and encourages this patient involvement. They've even issued patient guides on many kinds of healthcare-associated infections to help people know how to take action.12 Use this link to view the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection: http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/ca_uti/cauti_faqs.html.

Here's my professional FAQ advice that I give to people who may need a urinary catheter while they're hospitalized:

Q: What can a patient or advocate do to prevent a healthcare-associated UTI?

A: The first and most effective way is to avoid having a urinary catheter whenever possible. Even in critical care patients, use of a urinary catheter is often unjustified. But if you must have one, the catheter should remain in place for the shortest possible time. The longer a urinary catheter stays in, the greater the risk of infection.13

It's hard to believe, but studies show, that more than 50 percent of hospitals do not monitor the length of time catheters remain in place after they are inserted.11 An even greater concern in one study is that over 50 percent of healthcare workers failed to specify the reason why each patient needed a catheter or failed to write down the exact date each patient's urinary catheter was first inserted.14

Some hospitals are responding to this problem with the simple practice of putting a reminder on patients' charts to alert healthcare workers when a urinary catheter is in use and to ask for a specific “stop” date when the catheter would be removed. Hospitals using this approach were able to decrease the duration of catheter usage by 37 percent and, in fact, decreased infections by 52 percent.13

Q: How can I know if a urinary catheter is really necessary?

A: If you can't empty your bladder, you need a catheter, but that doesn't mean you need it for a long time. Even if you can urinate normally, your doctor may order a catheter when your urine output needs to be monitored. Because the urine flows into a bag, it's easy to measure. Although catheters should be removed as soon as possible, orders for urine monitoring often aren't reviewed and canceled. As a result, each extra day you continue with the catheter means an additional 3–7 percent chance of getting bacteriuria.7 You can help to prevent an infection by asking the doctor every day whether you still need the catheter and for what reason.

Q: How can I know when a urinary catheter isn't necessary?

A: Urinary catheters should not be used to obtain a urine specimen if a patient can void normally and should never be used as a substitute for nursing care. Healthcare workers often decide to keep patients catheterized when a shortage of staff members makes it more convenient to have patients void that way, rather than having to help them or having to change soiled bed linens. This is not good medical practice. Don't let it happen to you or anyone else!

Q: What should I watch for when my catheter is inserted or replaced?

A: It's important to keep the catheter clean and free from germs that cause infections. The biggest chance for bacteria to get into the catheter is when it's inserted. That's why inserting or replacing a catheter should be done only by properly trained people using sterile or “clean” technique.

When your catheter is being cleaned or replaced, make sure your nurse starts by washing his or her hands with soap and water or by using an alcohol-based sanitizer and then puts on fresh sterile gloves. Next, the nurse should clean your skin in the area where the catheter will be inserted before opening a sterile pack to remove a fresh catheter for insertion.

Watch every step carefully! For example, it sometimes happens that doctors and nurses will put sterile gloves on without first cleaning their hands or will remove a clean catheter from a sterile pack only to place it on a dirty tray. If you see something, say something!

Q: Are any precautions needed when the urine bag is emptied?

A: When urine must be taken from the bag or the bag needs to be emptied, the healthcare worker must clean his or her hands rather than just putting on gloves. When emptying the catheter or removing a urine sample, the catheter shouldn't be disconnected from the drain tube; this prevents bacteria from getting into the catheter tube. Also be sure that the drainage spout doesn't touch anything that could be dirty.

After emptying, the urine bag must be returned to a secure place below the patient, so that there is always a downward flow. If the bag is placed on top of your bed or on top of you in the bed, there is a chance of bacteria flowing upward into your body. But don't put it on the dirty floor! Check to see that there are no twists or kinks in the tubing. If the catheter stops draining urine into the bag, report it so the problem can be corrected.

DID YOU GET AN INFECTION?

Sometimes even careful hygiene isn't enough to prevent a catheter-related UTI. But when you're in the hospital recovering from illness or an operation and feeling generally uncomfortable, you may not even realize that you've developed an infection. Here's what you should look for:

- Redness or swelling around the area of the catheter. That can also be a sign that your catheter needs to be cleaned or changed.

- Burning or pain in your lower abdomen (below your stomach)

- Blood, stones, or sediment in your urine

- Fever or chills

- The catheter drains very little urine, even though you're drinking enough fluids

Don't wait to report a problem! While you're waiting, the infection keeps spreading. Of course, some of these symptoms could be caused by other problems, so check with a doctor or nurse to know for sure. If an infection is suspected, a sample of your urine will be sent to the laboratory to check for bacteria and identify which kinds of bacteria are present.

As this suggests, you can expect to be treated with antibiotics for any catheter-associated UTI. Not just any antibiotic will do. As you'll remember from reading about methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), many strains of bacteria have become resistant to standard antibiotics. Accredited hospitals are required to keep records of which antibiotics have not been effective in treating recent bacterial infections in your geographic location. Be sure to ask if your doctor has checked these records to select the most effective antibiotic against the bacteria you're fighting. This is extremely important—it could save your life!15

ONE MORE THING

Do all these instructions seem like too much to remember and too much to worry about? I've worked with hundreds of patients in hospitals all across the country, and I can assure you that it's not hard to protect yourself from infections. I know you CAN do it! In fact, there's just one basic thing you have to remember:

If you don't see healthcare workers wash or sanitize their hands before approaching your bedside, always ask them to do so.

Actually, there is one more thing:

Always wash or sanitize your own hands frequently to keep them clean while you're in the hospital.

If you remember these two simple things, you've already done most of the work. I told you it was easy.

To remind you of other infection-preventing strategies, here's a checklist you can take to the hospital in case you need a urinary catheter.

Checklist for Catheter-Associated UTI

- Remember to ask: Do I need the urinary catheter?

- Also ask: How long will I need the catheter?

- Remind yourself or your advocate to ask the doctor each day whether you still need the catheter and, if so, the reason you still need it.

- During catheter insertion, be sure the doctor or nurse starts with handwashing and is careful to keep the catheter sterile, within the sterile area, and not opened and placed down on your tray table.

- Keep the urine bag below you at all times.

- Remember the question: Did you wash or sanitize your hands?

WHAT WOULD YOU DO?

Now that you know the facts about catheter-associated UTIs, would you feel empowered to help yourself or a loved one who needs a urinary catheter during her hospital stay? Put on your own Sherlock Holmes, hat and read through this story about Julie Rich, told by her daughter. Would you have done anything different than what her daughter did?

Julie Rich's Story

My mother is 65 and she has always been very healthy. That is, until she went in for what was supposed to be simple, routine, day surgery.

Whenever Mother did heavy housework or lifted things, she kept wetting her pants. She didn't like wearing urine pads, so the doctor told her to have something called a sling put in to hold her bladder up. He arranged a morning appointment for her at our hospital's outpatient wing to have the sling surgery done.

When the surgery was finished, they sent her home wearing a catheter, but it didn't seem to be draining the urine out right. So after the weekend, we took Mother back to the doctor's office. The nurse told us the catheter had been put in upside down. She fixed it and gave Mother an appointment to come back in a few days.

By that time, Mother wasn't feeling well. The nurse took the catheter out, but it didn't seem to help. Back home, Mother was sleeping all the time and complained that she was having chills.

When we finally took her temperature and found that she had a fever, we went back to her doctor's office for a third time. The two times before, the actual doctor had never seen her. It had always been the nurse. This time, the doctor came in and immediately told us Mother has a ‘Staph’ (a Staphylococcus aureus) infection. He kept telling her, ‘What are you doing here? You should be at the hospital!’

We went directly to the hospital. They admitted her, and within a few days, they said she now had sepsis. That's a really dangerous infection where bacteria get into your blood. They needed to do another surgery to take the sling out because it was infected. But then she got blood clots and had to have another surgery to take those out.

After many, many days in the hospital and lots of vancomycin (an antibiotic) and other drugs, she left the hospital and went to a nursing home to finish her intravenous antibiotic therapy. When she came home, she was still taking lots of medication and needed to use oxygen.

This has been very hard on us, because Mother is only 65 and has never been sick before. I believe this was all caused by Staph and sepsis.”

Regards,

Julie's Daughter

I had the opportunity to contact Ms. Rich and share the story as told by her daughter. At the end of her note to me she said:

I tell everyone “Don't have any elective surgery.” It's not worth it.

What went wrong? Here was a healthy woman, under age 70, who had elective surgery (meaning it was not an emergency) and ended up with complications. What do you think went wrong?

Let's look at the facts. We know that within 48 hours after a catheter is inserted, it becomes surrounded with bacteria. In this case, Mrs. Rich went back to her doctor's office after 48 hours, and it was determined the catheter was not inserted correctly. The nurse “fixed it” and said to come back in a few days. What probably happened is that “fixing it” moved the catheter in a way that let the surrounding bacteria pass into Mrs. Rich's bloodstream. Because she had just had surgery and her immune system was weak, her body didn't fight off the bacteria. In a short time, she developed sepsis (infection in the blood).

What do you think Julie Rich and her daughter should have done? Here's what I would have told them:

- Make sure you really need a urinary catheter and that it will be kept in for the shortest time possible.

- Know the warning signs of infection and act quickly to get medical care.

- If there is a problem after surgery, insist on speaking with your doctor.

- Go to the emergency room if your doctor is not available to see you.

- Never allow a healthcare professional to try to fix a catheter that has been inserted incorrectly. Have them remove the catheter and determine whether it is still needed. If so, a new sterile catheter should be used.

It might also have been a good idea to give Julie an antibiotic after “fixing” her catheter, to prevent bacteria from continuing to multiply in her bloodstream. Fortunately, she survived.

You are an empowered patient, so don't be shy about demanding better care than Julie received.