2 Diseases of Conquest and Colony

Humanity does not have to live in a world of plagues, disastrous governments, conflict, and uncontrolled health risks. The coordinated action of a group of dedicated people can plan for and bring about a better future. The fact of smallpox eradication remains a constant reminder that we should settle for nothing less.

—William H. Foege, House on Fire1

If you are over 30 and not from Ethiopia, it may be impossible to think of that country without images of children starving. In October 1984, BBC broadcast news of a famine occurring amid a long, bitter civil war in the Tigray province in the Northern Highlands. The Derg, the military dictatorship in power, had withheld food aid and used the famine to push rural residents into camps to deprive the rebels of their supporters. The images from those camps were appalling: listless, emaciated girls and boys in dusty camps with bellies protruding, flies crawling across their faces and eyes. A half of a million people died in the famine. The footage inspired efforts to raise relief funds, including a Christmas song by British pop stars (“Do They Know It’s Christmas?”), another song by international recording artists (“We Are the World”), and simultaneous live concerts in London and Philadelphia. My sister had the 45 record of the British single and my siblings and I sang our off-key inquiries after Africans’ cognizance of Christmas for months. (As it happens, most Ethiopians are Christians and were likely aware of the holiday.)2 Footage of Ethiopia’s famine featured in NGO fundraising ads for years. Development economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo have said that “no single event affecting the world’s poor has captured the public imagination and prompted collective generosity as much as the Ethiopian famine of the early 1980’s.”3

Figure 2.1

UK supergroup Band Aid, Columbia Records (1984). Image courtesy of Andrea Bollyky Purcell, published pursuant to fair use.

Today, the health and nutrition of most Ethiopians is much improved. Malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and most other infectious diseases have declined. Premature deaths from malaria alone fell by a whopping 96 percent since 2005.4 Those improvements have contributed to the two-thirds decline in infant mortality in Ethiopia since 1990. With fewer children dying, families and governments are making greater investments in education. Enrollment of primary-school-age children in Ethiopia went from 22 percent in 1995 to 74 percent in 2010. The average Ethiopian woman now gives birth to four children instead of eight.5 Ethiopia is one of just eight countries worldwide where the life expectancy of women has improved by ten or more years in the short span of a single decade. The eight-year gains in Ethiopian men’s life spans over that time are nearly as impressive.6

Figure 2.2

The skyline of the downtown business district in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015. Photo: Getty Images.

With improved health, the population in Ethiopia is growing fast, swelling from 48 million in 1990 to 104 million people in 2017, and the economy is keeping pace.7 Ethiopia is one of the world’s most rapidly growing economies over the last five years, according to the International Monetary Fund. Nearly every street in central Addis Ababa, the country’s capital, seems to feature a high-rise under construction. Having traveled to Ethiopia for work over the years, I find it hard to come away unimpressed by the transformation. One measure of global esteem for the great health advances made in Ethiopia came with the election of Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the country’s former health minister, to lead the World Health Organization—the first African to ever hold that post.

The recent progress against plagues and parasites is not limited to Ethiopia. The rates of infectious diseases are falling dramatically everywhere, even in developing countries where the economy is not growing as fast as Ethiopia’s. The following data and figures come from the Global Burden of Disease project at the University of Washington and highlight these positive trends.8

Malaria deaths worldwide decreased by nearly 27 percent from their peak in 2003, when that disease annually claimed roughly one million lives. Deaths from HIV/AIDS globally have fallen from 1.9 million in 2005 to 1.1 million. Tuberculosis, which once killed 80 percent of those infected in nineteenth-century Europe, now takes about a quarter fewer lives than it did just a decade ago. Deaths from diarrheal diseases, a terrible killer of children in poor countries, have also fallen by more than a fifth over the same period. Measles, the disease that once ravaged the Inca and Roman empires, causes one-quarter of the deaths (68,220) that it did just a decade ago.

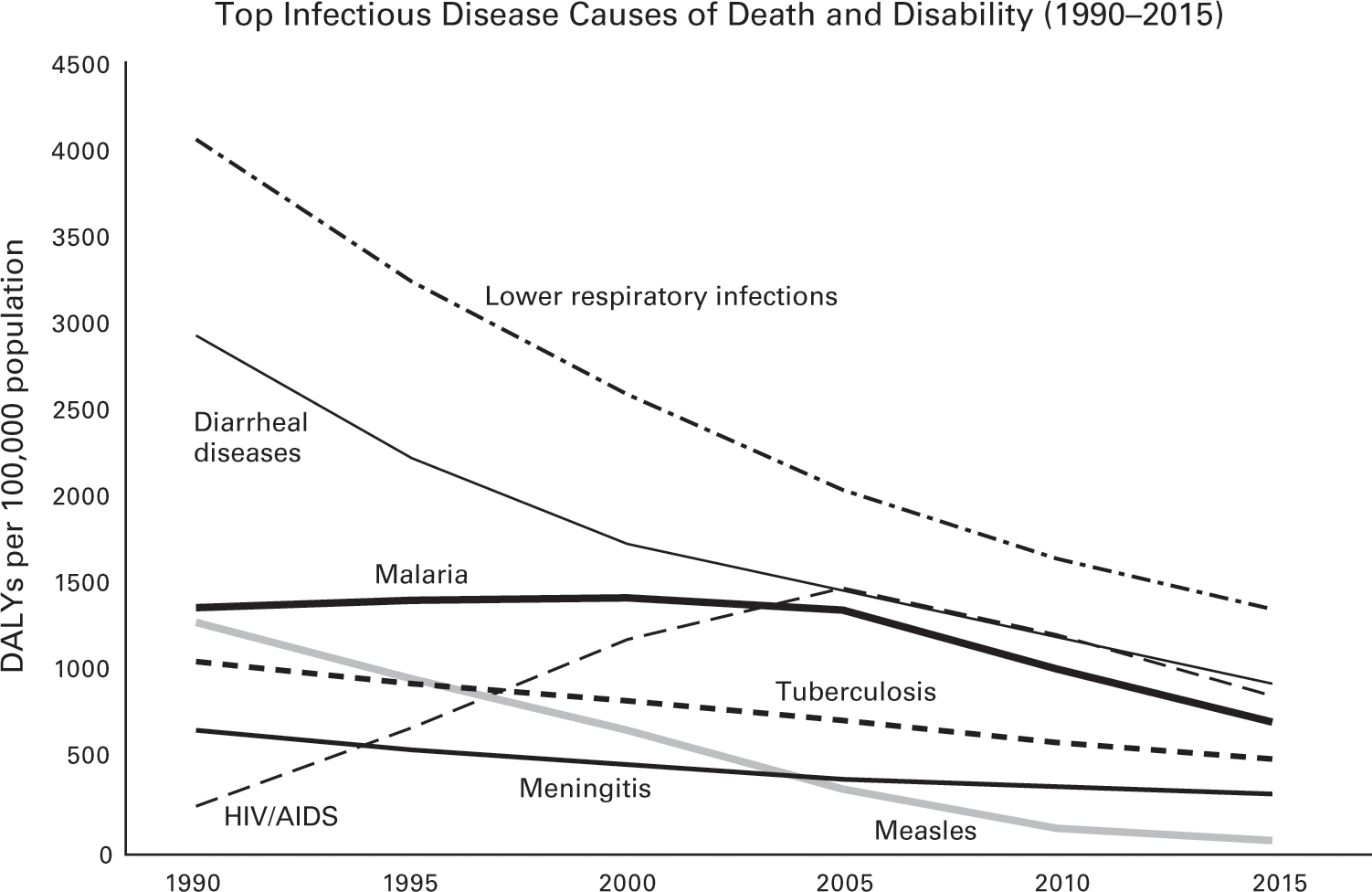

Deaths from most of the exotic parasites, bacterial blights, and obscure viruses that are largely confined to the poorest countries in tropical regions are also down sharply.9 Rabies and leishmaniasis each kill half as many people as a decade ago. The death toll of African trypanosomiasis, a parasitic disease also known as sleeping sickness, has decreased by more than three-quarters. The list goes on. As figure 2.3 shows, there has been an across-the-board global decline in the death and disability caused by all of the major infectious diseases (as measured here in disability-adjusted life years or DALYs).

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2015.

The progress in reducing infectious diseases has reverberated through the other traditional measures of health. In 1960, nearly one in four children born in developing countries died before his or her fifth birthday. The rates in sub-Saharan Africa were even higher.10 As a result of the improvements in health, there has been a staggering 78 percent decline in child mortality in lower-income countries over the last fifty-five years. The rate of child death has decreased in every single developing country in the world. There are no exceptions. Figure 2.4 shows the drop in child mortality by geographic region. The progress has been spectacular.

Data source: UN Population Prospects.

As the mortality rates of children have fallen, so has the need for women in lower-income nations to have so many of them. In the early 1960s, women in developing countries gave birth to six children, on average, over the course of their lives. By 2010, that rate had plunged to roughly three children, although, as figure 2.5 shows, the pace of decline has been slower in sub-Saharan Africa. Fertility rates are important because childbirth affects women’s health, especially in nations with poor health care, and having too many children too early can keep women from getting an education and entering the workforce. The declining birth rates in lower-income countries have helped reduce the annual number of maternal deaths, which has fallen by 230,000 since 1990. The lives of several million women in poor nations have been saved over the last twenty-five years.

Data source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

The dramatic gains in health have led to stunning improvements in the average life expectancy of people born in developing nations. In 1990, a newborn in a low-income country could expect to live to be 53 years old. By 2015, that metric had improved to 62 years. In those twenty-five years, the gap between the life expectancy of a baby born in a poor country versus one born in the average wealthy nation has shrunk nearly 18 percent.

Alongside the reductions of infectious diseases, the lives of people in poor countries have clearly improved. In 2015, for the first time in history, less than 10 percent of the world’s population was living in extreme poverty, defined by the World Bank as living on less than $1.90 per day. Seventy-one percent of the people on the African continent now have access to safe drinking water.11 The relationship between better health and these broader economic and infrastructure improvements, discussed at greater length in the next chapter, is still much debated. What is certain is that the decline in infectious diseases in lower-income nations is a remarkable achievement, perhaps among the greatest in human history, freeing hundreds of millions of people from the grip of an early death and a life of painful disability.

The present gains against pestilence are different from those in the past. Reductions in infectious disease that took centuries to manifest themselves in countries that are wealthy today took place within a generation or two in still-poor nations. These recent declines in plagues and parasites have also materialized in troubled countries with dysfunctional governments. In Nepal, a poor country only a few years removed from a Maoist insurgency, life expectancy has increased by eleven years since 1990, reaching an average of 70 years in 2015. Many of the other countries that have increased their life expectancy by more than a dozen years would not lead many readers’ lists for least troubled nations either: Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, Maldives, Niger, Rwanda, Timor-Leste, Uganda, and, of course, Ethiopia. Donor-funded, treatment-driven initiatives in Ethiopia and other poor nations have helped achieve remarkable reductions in plagues and parasites in Ethiopia and other poor nations, but have not resulted in the strong public health systems and more responsive governance that generally accompanied infectious disease control elsewhere. The model for these international aid initiatives was first pioneered in military and colonial campaigns against plagues and parasites.

The Colonial and Military Roots of Global Health

For most of human history, plagues, parasites, and pests were a domestic affair. States began negotiating agreements with each other on infectious disease control and sanitation only in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was the same era when governments were concluding international treaties on telegraphy, the postal service, weights and measures, and time zones. The basic purpose of all these treaties was the same: standardization to facilitate trade. Quarantine was the principal means of containing the microbes and plagues that arrived at ports and rail stations, but governments often abused the practice to benefit their own merchants or punish other nations.12

The first international agreement on the quarantining of ships and ports was finalized in 1892.13 In 1902, the International Sanitary Bureau, which later became the Pan American Health Organization, was established to help coordinate infectious disease control.14 Five years later, the International Office of Public Hygiene was created to oversee quarantine rules and to share statistics from health departments around the world. It had a staff of only a half dozen people and could hardly fulfill its mission.15 Nations, rich and poor alike, were still largely on their own in confronting the plagues and parasites that ravaged their citizens. As industrialized nations better understood the causes of infectious diseases, they invested more in domestic public health and sanitation and imposed fewer quarantines. Their interest in international health cooperation waned.16

International efforts to control infectious disease in poorer nations did not emerge from an enlightened sense of global solidarity in humanity’s fight against plagues and parasites. Instead, the roots of global health are in conquest and colonization. More attention has been given to the historical role that the tiny microbes accompanying armies and explorers played in toppling grand empires, but infectious diseases also doomed many expeditions and encumbered colonies. Investing in infectious disease control facilitated conquest, made the tropics habitable for settlers, and improved the productivity of local laborers. It also advanced humanitarian and moral goals of empires and eased tensions between Western colonizers and indigenous peoples.

Today’s wealthy governments are still driven by that same mix of self-interest, geostrategic priorities, and humanitarian concern as they seek to address health concerns in poorer nations. Those actions do not always correspond with the biggest sources of death and disability. The colonial and military roots of global health also help explain the way that international aid initiatives traditionally sought to prevent and treat plagues and parasites in developing countries—with scientific interventions deployed in targeted campaigns, rather than through improving local governance or reducing poverty and inequity. A brief history of smallpox and malaria, and the different ways that these diseases were addressed in wealthy and poorer nations, helps tell the story.

The Spotted Plague

Smallpox, one of the greatest killers in human history, is believed to have begun life as a gerbil virus. That virus jumped from those African rodents to people and camels roughly 3,500 years ago and spread along trade routes to the early urban centers of southern Asia and the Nile Delta region.17 Egyptian mummies dating back to 1155 BCE, including Pharaoh Ramses V, bear telltale pockmark scars that may be the earliest evidence of the disease.18 In the centuries that followed, smallpox did inestimable damage. In the twentieth century alone, the disease has been estimated to be responsible for as many as 300 million deaths (more than three times the number killed in that century’s wars).19

The path to smallpox’s poxes started with the sufferer inhaling infectious material left from a past victim of the disease. Once inside, the virus entered the lymph nodes, multiplied, and spilled out into the bloodstream. A week or so later, the symptoms began with a headache, fever, pains, and vomiting. Three days after that, the skin erupted in waxy, hard, and painful pustules—spots that spread everywhere, including in the mouth and throat, and pressed together like a “cobblestone street.”20 Bacteria often contaminated those pustules, leading to abscesses and corneal ulcers that could, in turn, lead to blindness. Between 20 and 50 percent of victims perished from the disease, often as a result of septic shock.21 In regions where smallpox was endemic, it was mostly a threat to children under a year old. Among populations where the disease was unknown, however, all were susceptible.

The risk that smallpox posed to people without prior exposure made it one of history’s great diseases of conquest. But that is a view of history told by its victors. Smallpox has also been a major reason for military disaster and disruption of empires, and not just among the Amerindian population. The Huns were repelled from Gaul and Italy by an epidemic of a disease believed to be smallpox, reportedly spread after the beheading of a bishop who was a survivor of the disease. That bishop later became known as Saint Nicaise, the patron saint of smallpox victims.22 The first major battlefield defeat of the United States occurred after a smallpox epidemic disabled half of the Continental Army at the Siege of Quebec during the early days of the Revolutionary War.23 Some claim that smallpox is the reason that Canada remains part of the British Commonwealth.24 A smallpox outbreak saved the British again in 1779, thwarting a naval invasion of England where French and Spanish ships outnumbered their English counterparts by two to one.25

Smallpox remained a leading cause of death in Europe into the late eighteenth century; it played a major role in dismantling the secession plans of many royal families. Among those who perished from smallpox were Emperor Joseph I of Austria; King Louis XV of France; Tsar Peter II of Russia; King Luis I of Spain; Queen Ulrika Eleonora of Sweden; and Prince William, the eleven-year-old sole heir of Queen Anne of England, the last of the Stuarts.26

In 1796, Edward Jenner developed a vaccine for smallpox derived from a virus that was infecting cows but may have been horsepox.27 It was the first truly effective medical intervention for preventing an infectious disease. Unsurprisingly, royalty and political leaders in Europe were early to embrace and actively encourage use of the new vaccine. New health laws to promote smallpox vaccination campaigns were adopted, first in northern Italy and Sweden, then in England and Wales, and later in France and Germany. After a smallpox epidemic killed China’s emperor, Japan sent a mission to Europe to study vaccine production and adopted compulsory vaccination a few years later.28 The dowager empress in Russia ordered that the first orphan vaccinated for smallpox be named Vaccinoff and supported for life by the state.29 In the United States, Thomas Jefferson was an early enthusiast of smallpox vaccination for his young nation, vaccinating himself, his family and neighbors, and the last surviving members of the Mohican tribe, who happened to be visiting.30

Immunization programs produced dramatic declines in smallpox deaths in these early adopter nations, but the programs were also victims of their own success.31 As smallpox rates plummeted, antivaccination campaigns gained ground, especially in immigrant and rural communities wary of state intrusion. Fierce pushback from these groups ensued, particularly in Britain and the United States, and compulsory immunization was scaled back in several nations.32 The struggle over smallpox immunization forced governments to grapple with the hard balance between ensuring the public good and respecting individual rights.33 These struggles paved the way for the adoption of other forms of social regulation including compulsory schooling and military service.

Smallpox is also notable as the first disease to have demonstrated the difference that effective infectious disease control could make in war. The decision of General George Washington, himself a pockmarked survivor of the disease, to inoculate his troops at Valley Forge against smallpox may have saved the colonial war effort against a British army that was less susceptible to the disease.34 A smallpox outbreak spread by troop movements and refugees from Paris in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War killed half a million people in Europe, including 20,000 French soldiers, but only 500 of the well-vaccinated and victorious German troops.35 After the Franco-Prussian War, military and colonial investments in infectious disease control and research increased, especially for mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria.

The Cost of Failing to Outwit a Mosquito

Like smallpox, malaria is an old disease, caused by a parasite that emerged as a major killer of people thousands of years ago, around the advent of agriculture.36 Malaria is not deadly to the cold-blooded mosquitos that carry it, but the parasite rapidly multiplies in the red blood cells of warm humans and bursts forth, inciting fever and debilitating weakness. When the parasitized red blood cells accumulate and clog the blood vessels of the brain, cerebral malaria ensues, which is fatal if untreated. The fever caused by malaria enables the parasite to move freely in the bloodstream for a day or two, when another mosquito may bite the sufferer and suck up the parasite, starting the cycle anew. The symptoms of malaria are more severe in people without prior exposure to the disease and can be especially deadly for children. Immunity to malaria builds up slowly and is quickly lost without repeated contact. The Anopheles mosquitos that carry the malaria parasite do well in any warm weather environment with standing water and thrive in the wells and ditches in villages, military camps, and farms where there are enough people to sustain transmission of the parasite.

The role that malaria has played in history has been as more of a disease of colonies, a hindrance to exploration and settlement, than a help to military conquests. The famed malariologist Paul Russell led the US Army’s efforts against the disease in World War II and once wrote of malaria’s toll:

Man ploughs the sea like a leviathan, he soars through the air like an eagle; his voice circles the world in a moment, his eyes pierce the heavens; he moves mountains, he makes the desert to bloom; he has planted his flag at the north pole and the south; yet millions of men each year are destroyed because they fail to outwit a mosquito.37

The strain of malaria that is endemic in Africa, Plasmodium falciparum, is particularly deadly to outsiders. For centuries, it repelled explorers and would-be conquerors of the continent. In the 1560s and 1570s, Portugal made several attempts to bring missionaries and armies from Europe to Mozambique and expand the empire’s African foothold inland, only to see malaria cut down priests and soldiers alike.38 In 1805, forty-two men accompanied Mungo Park, a Scottish doctor and best-selling author, in his expedition to reach Timbuktu, a city fabled to contain the treasure of Prester John. Forty-one of them died of malaria. Park and one other man survived until an ambush by Tuaregs forced them into a crocodile-infested section of the Niger River. Park’s son, Thomas, launched an expedition to find his father and also likely perished of malaria.39

Malaria has been hindering armies since the disease kept the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 221 CE) from expanding into the Yellow River flood plain and the Yangtze Valley.40 More than a thousand years later, the disease remained a major obstacle to military campaigns. More than a million soldiers suffered malaria during the US Civil War.41 During World War I, malaria bogged down troops in Macedonia, East Africa, Mesopotamia, and Palestine. In 1918, half of Britain’s 40,000 troops pursuing Turkish forces into the Jordan Valley were lost to malaria.42

Amid increased colonization and the two world wars of the twentieth century, more research was devoted to malaria and its control, but the fruits of that research emerged only after the disease had already declined precipitously in the prosperous nations of world. In the sixteenth century, malaria was once common enough in England and Northern Europe for the disease’s symptoms to earn references in the works of Shakespeare, Dante, and Chaucer. By 1880, however, improved drainage and extensive land reclamation had dramatically reduced the mosquito-friendly marshes that supported the disease. Greater mechanization of agriculture and improvements in rural housing further cut transmission rates.43

Progress in the United States also predated the development of effective pesticides for malaria-bearing mosquitos. Starting in 1912, the US Public Health Service, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, tested malaria control strategies to determine the most cost-effective approach and generate public support in the American South.44 Once the benefits of drainage for reducing malaria-spreading mosquitos and improving worker productivity were demonstrated, US public health officials solicited support from local businesses for their expansion. Lawsuits and federal regulations forced the booming US hydropower industry to change the design of dams to clear stagnant waterways and cut mosquito habitats further.45 By the time effective pesticides were developed and the US Malaria Control in War Areas program (which later became the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) began to use them to eliminate mosquitos, malaria rates had already plummeted. The United States went from having more than a million cases of malaria during the Great Depression to effectively eliminating the disease from the country by 1952.46

The opportunities for lower-income nations to adopt their own national and local measures to control infectious diseases like malaria and smallpox were limited. Many of these countries were poor, rural, and disrupted by conquest and colonization. The warmer climate in many of these nations meant a higher burden of tropical diseases. Malaria remains endemic today in ninety-one countries and territories, mostly lower-income nations.47 Smallpox, despite the availability of an effective vaccine, continued to kill hundreds of millions in lower-income nations over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.48

Eradication and the First International Health Campaigns

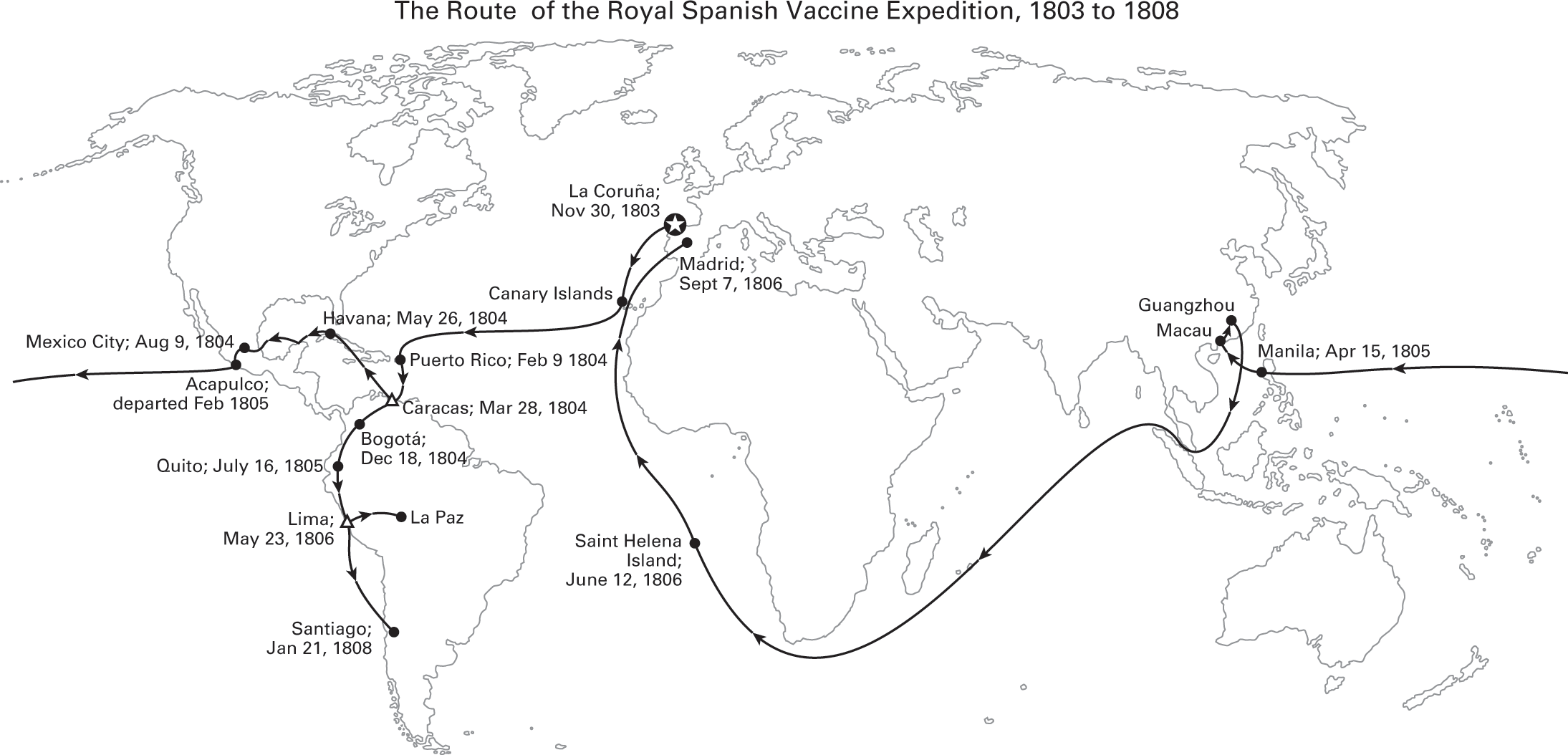

The first international campaigns to prevent infectious disease in poorer nations were the vaccination expeditions launched by the Spanish and British Empires shortly after Jenner’s invention of the smallpox vaccine. The British campaign, launched in 1802, targeted India. The Spanish Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition, which started in 1803, was even more ambitious—a decade-long effort that carried smallpox vaccine from Spain to the Caribbean, to New Spain (Mexico) and Guatemala, to Venezuela, down the Pacific coast of South America and up to its Andean provinces, and to the Philippines and China.49

To preserve the smallpox vaccine in warm climates and over long journeys, these early expeditions took advantage of two of its unique properties. First, the smallpox vaccine, unlike most modern vaccines, is a live virus (a hybrid of the smallpox and cowpox or horsepox viruses) that can be delivered through the skin. The vaccine was administered by rubbing it into a series of small cuts made with a knife, called a lancet (in later smallpox immunization campaigns, bifurcated needles were developed for this purpose). After a period of incubation, those cuts erupted into lesions that oozed fluid brimming with the hybrid virus. That serum could be harvested by squeezing those open lesions and using the fluid that emerged to vaccinate another person. Second, the incubation period before those lesions emerged was long, nine or ten days, which meant that only a few dozen passengers on these expeditions, instead of hundreds, could be used to sustain and relay the vaccine arm-to-arm around the world.

Figure 2.6

Adapted from Soto-Pérez-de-Celis, “The Royal Philanthropic Expedition of the Vaccine,” 2008; Franco-Paredes, Lammoglia, and Santos-Preciado, “The Spanish Royal Philanthropic Expedition,” 2005.

The passengers chosen for this purpose were orphans, some as young as five years old. A relay of children brought the smallpox vaccine arm-to-arm from Baghdad to Bombay to launch the British immunization campaign in India. Twenty-one Spanish orphans were used to transport the vaccine on the two-month journey from Spain to the Caribbean in 1804. The director of the orphanage, and the only woman aboard, also brought her son so that he might contribute to the mission.50 The process of harvesting the vaccine could lead to infections and fatal complications, and the British Sanitary Commissioner for Bengal reported that the “agony caused to the child was often intense.”51 Four of the children who participated in the Spanish voyages died.52 In later vaccination campaigns, calves were used to transport and harvest the vaccine before heat-stable and freeze-dried versions were invented decades later.53

These early vaccination campaigns had multiple purposes. The British and Spanish governments saw these missions as opportunities to generate goodwill and demonstrate the benefits of colonization at a time when there were few other cures or prophylactics for infectious disease. A healthier workforce increased the productivity of colonies, which depended on agriculture, textile production, and other labor-intensive activities.54 The safety of colonial officials also depended on the vaccination of those around them.55 But humanitarian interests were also at work.56 Charles IV (the Bourbon King of Spain) was committed to spreading the benefits of vaccination to the Spanish empire after his brother died of smallpox and his daughter was infected with the virus.57 Overall, the Spanish and British vaccine expeditions are estimated to have vaccinated as many as half a million people.58

International initiatives against malaria in lower-income nations began with colonial and army physicians working to address surges in the disease that colonization itself had helped cause. A growing demand for raw materials spurred the industrializing powers of Europe and the United States to shift their colonies to mining and plantation-style farms, and to build canals to transport the produced commodities. These changes transformed the physical landscape and concentrated large numbers of local laborers in settings conducive to the spread of malaria.59 As colonial governments expanded and civilian and military staffs grew, garrison hospitals and medical centers were established. These facilities mostly served Europeans, but sometimes had special wards for “natives.”60 The army and colonial doctors assigned to those sites later emerged as the first practitioners of tropical medicine, a new discipline focused on infectious and parasitic diseases.61

In 1880, Charles Laveran, a French physician working in a military hospital in Constantine, Algeria, discovered that a parasite caused malaria, rather than, as previously thought, the foul water and bad air that gave the disease its name (mal aria). Sir Ronald Ross, a British army surgeon working in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, discovered that mosquitos carried the parasite in their salivary glands and spread the disease through bites. Colonial and military health officials founded research institutions like the Liverpool and London Schools of Tropical Medicine, which developed the strategies to control malaria and trained generations of infectious disease specialists.62

One adopter of these strategies was William Crawford Gorgas, an Alabama-born army surgeon. He used the discoveries of Ronald Ross on malaria, and related research by Walter Reed about yellow fever, to conduct the first practical demonstrations of disease eradication via antimosquito campaigns. The ravages of malaria and yellow fever had thwarted French efforts to build a canal in Panama connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. As the chief sanitary officer of the US-led Panama Canal Commission between 1904 and 1913, Gorgas drained one hundred square miles of territory, applied millions of gallons of oil and kerosene to kill breeding sites, and paid children to hand-kill adult mosquitos. The campaign worked, cutting malaria cases by 80 percent, eliminating yellow fever, and allowing the successful construction of the canal.63 When Gorgas began his work, the death rate in the Canal Zone was three times higher than the continental United States; by the time he finished in 1915, the death rate in the Canal Zone had fallen to half that in the United States.64 Gorgas, together with former colonial health officers and veterans of the US Army Medical Corps, took this approach of military-style, single disease campaigns with them to the Rockefeller Foundation and the first international health institutions.65

The League of Nations was founded in the aftermath of World War I to prevent future wars through collective security, disarmament, and international arbitration of disputes. As part of that mission, the League established a health section that became known as the League of Nations Health Organization. That organization established a malaria commission in 1924 to assess and advance antimalarial strategies to address war-related surges of the disease in southern Europe, an effort that eventually expanded to Latin America and the Caribbean, and parts of Asia.66

Figure 2.7

A man spraying oil on mosquito breeding grounds in Panama. Reprinted with permission from the Library of Congress.

World War II spurred a furious expansion of those antimalarial strategies. Germany’s invasion of the Netherlands and the Japanese conquest of Java blocked the Allied powers’ access to quinine, the only effective antimalarial drug at the time, which was produced on Dutch-owned plantations in Indonesia.67 As the war pushed into the malarial zones of the Pacific and Mediterranean, the toll of disease mounted. At one point, in the early stages of the war, General Douglas MacArthur estimated that two-thirds of his troops in the South Pacific were ill with malaria.68 Whole divisions fell sick to the disease in the Battle of Bataan, helping the Japanese defeat US and Philippine forces. The American Forces Radio in the South Pacific broadcast so many messages about avoiding malaria that US troops dubbed it the “Mosquito Network.”69 In 1943, the US Army even drafted Dr. Seuss, writing under his real name Theodor Geisel, to pen a mildly racy cartoon pamphlet about avoiding the bites of Anopheles mosquitos. It begins with a keyhole view of a seductively posed mosquito and the line “Ann really gets around.” Despite those efforts, five hundred thousand US GIs are estimated to have contracted malaria during World War II.70

The US antimalarial research program at Johns Hopkins University tested thousands of compounds before developing chloroquine, the first new treatment of the disease since Jesuit missionaries documented the medicinal properties of cinchona tree bark (quinine) in the 1630s.71 The insecticide DDT was first tested as a means of controlling lice-borne typhus during the Allied liberation of Naples in October 1943 and used against malaria in the US Marines’ assault on Peleliu and Saipan.72 The success of those efforts led the United States to approve DDT for civilian use after the war.73 The insecticide was so effective that the last remaining malaria cases were eradicated from the United States in 1952 and, a few years later, from most of Europe.74 Its inventor, Paul Müller, won a Nobel Prize for his work on DDT in 1948.

The medical advances of World War II, combined with the development of antibiotics and vaccines beyond smallpox, facilitated rapid responses to disease threats and made unnecessary the slow, broad-based path that developed nations had pursued to better health.75 The horrors of World War II also inspired commitment in global leaders to build new forms of international cooperation to promote economic development and confront the humanitarian crisis left after the conflict. The World Health Organization (WHO) was established as part of the United Nations in 1946 and given a broad mandate to promote health. But it was not given the resources to match. Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union pushed the WHO to focus on rapid, high-impact infectious disease control programs, with the goal of helping to win the hearts and minds of developing nations, many of them beginning to throw off their colonial chains.76

Figure 2.8

Theodor S. Geisel, This Is Ann: She’s Dying to Meet You. Pamphlet, Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1943.

US support and the success of the DDT-led campaigns helped push the WHO to launch a global malaria eradication program in 1955, the first effort to eradicate an infectious disease from the face of the earth. Three years later, with the support of the Soviet Union, the WHO began a campaign to eradicate smallpox as well.

The goal of the WHO’s malaria campaign was to interrupt transmission of the disease by spraying DDT to kill the mosquitos that spread the disease and to identify and treat all those with the disease to prevent returning mosquitos from becoming reinfected. Within a decade, the campaign eliminated malaria from twenty-six countries—more than half of the nations participating in the campaign. In the other countries, malaria rates were driven down dramatically.77 But some of that progress was later reversed as mosquitos became resistant to DDT and use of the pesticide was stopped worldwide over environmental concerns (largely from the overuse of the insecticide in wealthy countries’ agriculture). By 1969, the WHO was forced to admit that the malaria campaign would never achieve its global goal of eradicating the disease, a major blow to the institution and its prestige. Still, by the time it was canceled, the malaria eradication program had protected an estimated 1.1 billion people from the disease at a cost of $1.4 billion over ten years, or roughly $10 billion in today’s terms.78

The smallpox eradication program accomplished even more for less. Smallpox had several advantages over malaria as a target for eradication. While smallpox still killed an estimated two million people per year in the late 1950s, it was endemic only in Brazil, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, Indonesia, and most of sub-Saharan Africa.79 The distinct pocking that the disease caused and the manner in which it spread (person to person, rather than via mosquitos) made smallpox easier to identify, track, and ultimately wipe out. Nevertheless, the smallpox campaign languished for years at the WHO with little support. A major turning point came in 1965 when President Lyndon Johnson, who needed an initiative to announce to mark the United Nations’ “International Cooperation Year,” threw the United States’ support behind an intensified antismallpox campaign, which was launched two years later.80

Ten years of heroic work and more than 370 million vaccine doses later, the eradication campaign brought the number of smallpox cases to zero. Ethiopia was the last country in the world where smallpox was endemic. The last case of smallpox was found on October 26, 1977, across Ethiopia’s border with Somalia, in a hospital cook named Ali Maow Maalin working in the town of Merka.81 The cost of the intensified smallpox eradication campaign was $313 million.82 In 1980, the World Health Assembly declared “the world and all its peoples have won freedom from smallpox, which was a most devastating disease sweeping in epidemic form through many countries since earliest times, leaving death, blindness, and disfigurement in its wake and which only a decade ago was rampant in Africa, Asia and South America.”83

Figure 2.9

Pasquale Caprari, WHO scientist, supervises malaria-campaign workers spraying a hut with DDT in Ghana in 1950. Photo: WHO/UN, Courtesy of WHO.

Figure 2.10

Ali Maow Maalin, who contracted the world’s last recorded case of endemic smallpox, pictured here in 1979. Photo: WHO/John F. Wickett, Courtesy of WHO.

The legacy of the smallpox campaign extends beyond that disease. Many of the men and women who directed that effort—D. A. Henderson, Bill Foege, David Heymann, and others—later became leaders in the new field of global health. The smallpox campaign is also remembered for demonstrating the viability of a new model for improving health in poor nations that was disease specific, coordinated by international agencies and infectious disease specialists, and implemented by local staff and volunteers. That approach is now known as a “vertical” program because it is directed internationally (from above) and targets just one disease, often with a single intervention such as a vaccine.84

Adoption of this approach to improving global health was not inevitable. The first director of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation, Wickliffe Rose, argued that the purpose of the foundation should not be to eradicate a particular disease, but to demonstrate the benefits of professionally run public health programs to inspire local agencies and policymakers to take up that cause permanently.85 He was overruled and ultimately pushed out, with Frederick Gates, Rockefeller’s philanthropy advisor, arguing that Rose’s mission was one that “a thousand years will not accomplish.”86

Day-to-day innovations and adaptations of local officials in fact played a significant role in the success of the smallpox eradication campaign in countries like India.87 Some WHO staff advocated that the smallpox eradication campaign should work more through local health centers to build up the capability of basic health services. But that strategy, whatever its long-term benefits may have been, cost more and resulted in lower vaccination rates.88 The vertical model, which first evolved from colonial and military efforts to control threatening tropical diseases, continues to prove remarkably effective in reducing the rates of targeted infectious diseases. That progress has not, however, been accompanied by the broader gains in responsive governance that occurred with infectious disease control in the past.

The Path to Better Health in Poorer Nations

Not all the progress against infectious diseases in lower-income nations after World War II relied on international aid campaigns or medical inventions. China, Costa Rica, and Sri Lanka, among others, found cheap and ingenious ways of preventing infectious disease. Many but not all of these first-mover governments were socialist and, at the time, based their legitimacy on their ability to improve health, education, and literacy for the masses. These nations benefited from the technical support of the WHO, but their biggest health gains were achieved through homegrown, low-cost strategies. These methods included training peasants from the community to serve as health extension workers, dig pit latrines, assist with births, and extract the parasite-carrying snails that lived in the trenches around villages.89 Between 1946 and 1953, life expectancy in Sri Lanka rose twelve years.90 Life expectancy in Jamaica and Malaysia increased by a year annually for more than a decade.91 These health gains occurred well before the economic growth that China and these countries would later achieve.92

But most of the reduction in plagues and parasites that occurred in developing nations after World War II was dependent on antibiotics, vaccines, and, to a lesser extent, aid. This was in part a matter of timing. Effective medicines were available when these countries began their health transitions, and so the governments and health workers of these nations put those medicines to good use.93 The demographer Samuel Preston estimates that vaccines and antibiotics drove half of the declines in death rates in developing countries through the late 1970s.94 Foreign aid played a small but important role in these early successes, developing new low-cost health measures, training medical personnel, and expanding access to effective medicines. Income was more important than before; emerging countries with greater wealth could afford to spend more on vaccines, antibiotics, and improvements in obstetrics. Child mortality fell by 75 percent or more in Latin America, East Asia, and the Middle East by 2000, a spectacular rate of decline that far exceeds what had occurred in wealthy nations. The health gains extended even to countries with nascent public health systems, poor living conditions, and high rates of malnutrition.95

But many developing countries, especially the poorest and most conflict-ridden, lagged behind. In 1990, there were nearly two dozen countries where as many as 175 children out of 1,000 died before the age of five and infectious diseases caused the majority of death and disability.96 Dramatic improvements in the health of these poorest nations would come only after the international response to HIV/AIDS, an epidemic that, at one time, had threatened to wipe out all the health gains that preceded it.

HIV/AIDS transformed global health, elevating infectious diseases as a foreign policy priority and helping to mobilize billions of dollars to research, develop, and distribute new medicines to meet the needs of the world’s most impoverished people. The HIV epidemic, which began in the 1980s, has been responsible for 35 million deaths worldwide (as of the end of 2016).97 More than two-thirds of HIV cases and three-quarters of HIV deaths took place on the African continent.98 At its height, the epidemic reduced life expectancy by up to fifteen years in several sub-Saharan African countries. A quarter of all adults in Botswana, Swaziland, and Lesotho contracted the disease. It wasn’t until 1998 that an international crisis emerged as it became publicized that many people in sub-Saharan Africa and other lower-income nations were dying without access to the life-saving treatments that had changed the course of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in wealthy nations.

Two developments sparked that international controversy. First, global trade talks established the World Trade Organization (WTO) and led to commitments that member countries must adopt minimum standards of intellectual property protection including patents on medicines. Second, life-saving antiretroviral medicines were developed for HIV/AIDS in response to the outbreak of the disease in the United States and Europe.

Pharmaceutical companies, concerned about undercutting their developed country markets, adopted internationally consistent prices for these drugs. In 1998, antiretroviral drugs cost more in South Africa, on a per capita GDP-adjusted basis, than in Sweden or the United States.99 Protests spread, disrupting international HIV/AIDS conferences and WTO meetings in Seattle in 1999.100 Trade disputes and court battles ensued over compulsory licenses, a tool that allows governments to circumvent a patent without the consent of its owner. Popular support for the pharmaceutical industry and international trade plummeted.

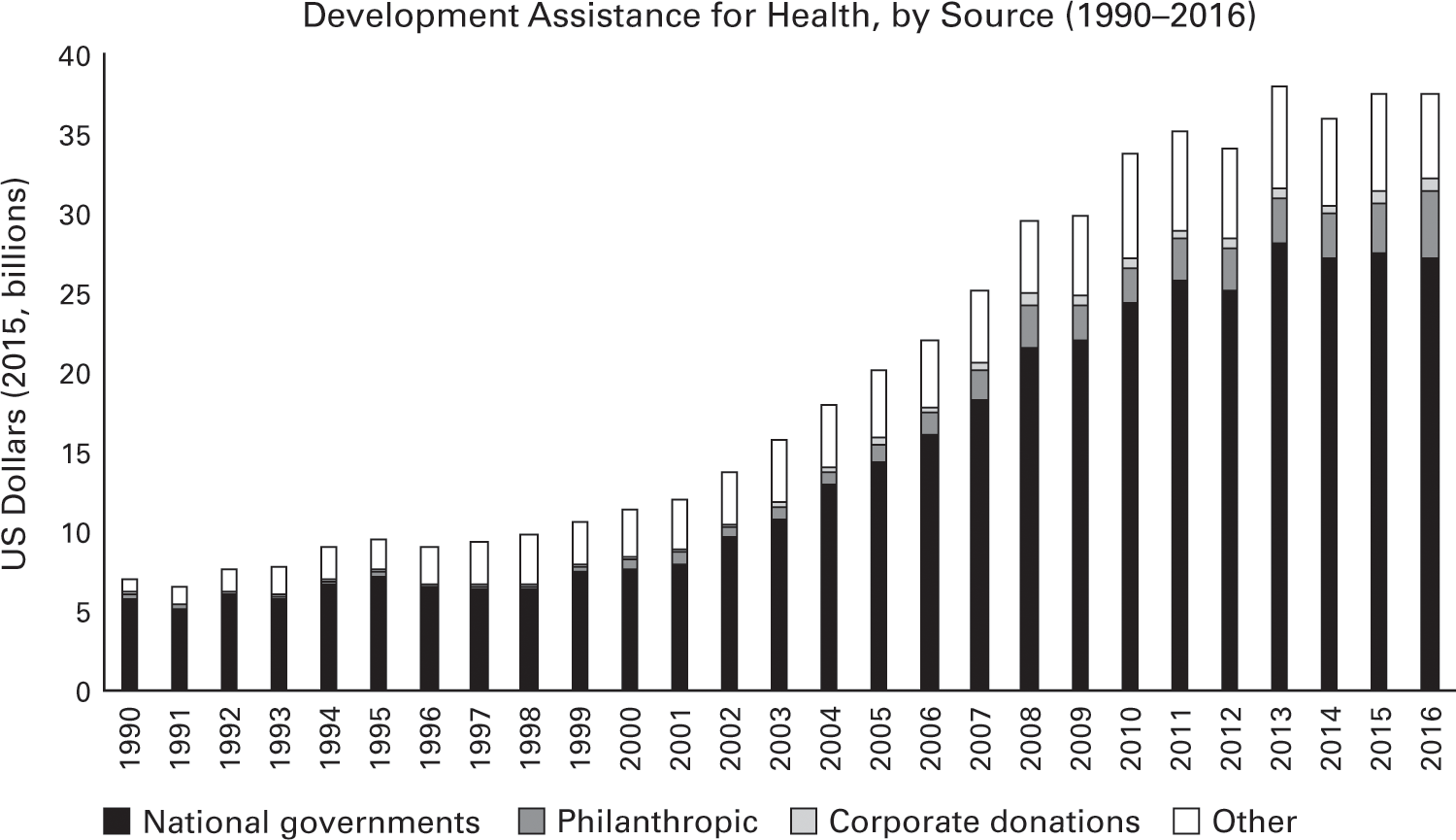

Amid the crisis, international investment in improving the health of developing countries began to rise. Aid to address infectious diseases in poor countries rose more than 10 percent annually over the next decade, expanding from $10.8 billion to $28.2 billion.101 Funding for research into new treatments for HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases rose thirty-fold over that time, to more than $3 billion.102 The US government, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and other donors established new programs to provide drugs and vaccines to the world’s poorest. These included the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi) in 2000; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund) in 2002; and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003. Drug companies and universities donated or voluntarily licensed their patents on medicines to treat infectious diseases for which there was little demand in wealthy markets. Competition and voluntary price cuts reduced the price of antiretroviral treatment in poor countries from $12,000 per year in 1996 to $200 per year in 2004.103 More than ten million people living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa are on those lifesaving medicines today, up from just one hundred thousand in 2003.104

Figure 2.11

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Financing for Global Health (2016).

Together, these efforts have delivered treatments, insecticide-treated mosquito nets, and immunization to millions, dramatically reducing the burden of plagues and parasites and saving many lives. Infectious diseases are no longer the leading causes of years of life lost to death and disability globally. Since 2005, rates of the infectious diseases targeted by global health initiatives, like HIV, malaria, measles, and Guinea worm, have been the ones to decline the fastest.

Amid this welcome progress, however, are worrisome signs for the future of international health initiatives. An idiosyncratic mix of motivations fueled the recent surge in investments to fight infectious diseases. As in the era of conquest and colony, some of these motivations were humanitarian and some were geostrategic. In deciding to launch the PEPFAR program, President George W. Bush reportedly asked how the United States would be judged if it did not act to address a preventable and treatable epidemic of such magnitude.105 Increasing US global health spending also promoted positive views of the country on the African continent, at a time when the United States had launched an unpopular war in Iraq.106 Massive protests over pricey HIV/AIDS medicines also brought global attention to a long-standing problem—international systems for medical research and development were not responding to the health needs of developing countries—and spurred the drug industry and its supporters to do more to defuse the issue.107

This confluence of motivations has proven difficult to replicate in response to other global health challenges. As a result, while the burden of many infectious diseases has changed in poorer nations, the distribution of international aid targeting these diseases has not. For example, 30 percent of development assistance for health is still focused on HIV/AIDS, which is now responsible for 5 percent of the death and disability in lower-income nations.108

International AIDS programs have invested in partnerships, clinics, and local health personnel to deliver antiretroviral drugs and related services in lower-income nations, but they largely remain vertical, disease-specific programs. Even global health programs with wider objectives, such as improved maternal, newborn, and child health, have mostly followed the same vertical approach as the old eradication programs rather than investing in strengthening countries’ health systems.109

Health spending has increased in lower-income nations, but relative to wealthy countries, it remains low.110 All forty-eight governments in sub-Saharan Africa together spent less on health in 2014 ($67 billion) than the government of Australia ($68 billion).111 Health spending that same year by all low- and middle-income country governments, representing 5.9 billion people, was roughly the same spent by the governments of the United States and Canada, with a combined population of 360 million.112 In fact, research by economists Joe Dieleman and Michael Hanlon suggests that the governments of poor countries are shifting their resources away from the health areas targeted by aid donors.113

In many countries in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, rural patients must still travel long distances to get treatment even for common conditions. The government-run hospitals offer affordable or free care but are often overcrowded and understaffed. Basic medical equipment, such as rehydration fluids, disposable syringes, gauze, and the like, may be unavailable. More expensive machinery like X-ray machines and MRI scanners are often inadequately maintained.114 In many countries, medicines are still purchased out of pocket and are often beyond the means of poor households.115 Inadequate oversight of antibiotic use and overcrowding in hospitals in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and other lower-income nations is spurring resistance to medicines that helped make possible the recent miraculous gains against infectious diseases.116 Private investment is increasing in hospitals in India, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and a few lower-income nations, but that investment to date mostly benefits the small wealthy and middle classes.117

Given strained public health systems, limited personal wealth, and modest government health spending, many lower-income countries are vulnerable to health challenges that have historically not attracted much donor funding.

Death and Demography

A sunny equatorial climate and the perceived abundance of available land began drawing English settlers to start farms in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania in the 1920s. Scores of British doctors followed, working in government service or in missionary hospitals. In their free time, these British doctors did what British doctors often do: they started medical journals. The early pages of the Kenya Medical Journal and other publications were consumed with a great medical mystery: whether Africans were naturally predisposed to lifelong low blood pressure. A case of hypertension had never been recorded in the region and would not be seen until the early 1940s. Obesity was rare enough that Sir Julian Huxley, a British biologist, recorded with amazement that the only overweight person he saw in four months in East Africa was a woman who worked in the Nairobi brewery, causing him to entertain the possibility that beer might be fattening.118

Today, it is far easier to find cases of heart disease and obesity in sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, heart disease, cancers, diabetes, and other noncommunicable diseases are increasing rapidly in most developing countries.119 In 1990, these noncommunicable diseases caused about a quarter of the death and disability in poor nations. By 2040, that number is expected to jump to as high as 80 percent in some of these countries. At that point, the burden of heart disease and other noncommunicable diseases in Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Myanmar will be roughly the same as it will be in rich nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom. The difference is that shift from infectious diseases to noncommunicable diseases took roughly three to four times as long in those wealthy countries.120

Fewer people dying as children and adolescents from plagues and parasites helps explain why more people in lower-income countries are getting these noncommunicable diseases. People must ultimately die of something and, if it is not infectious diseases, it is more likely that death will come as a result of noncommunicable disease than via an accident, injury, or violence.

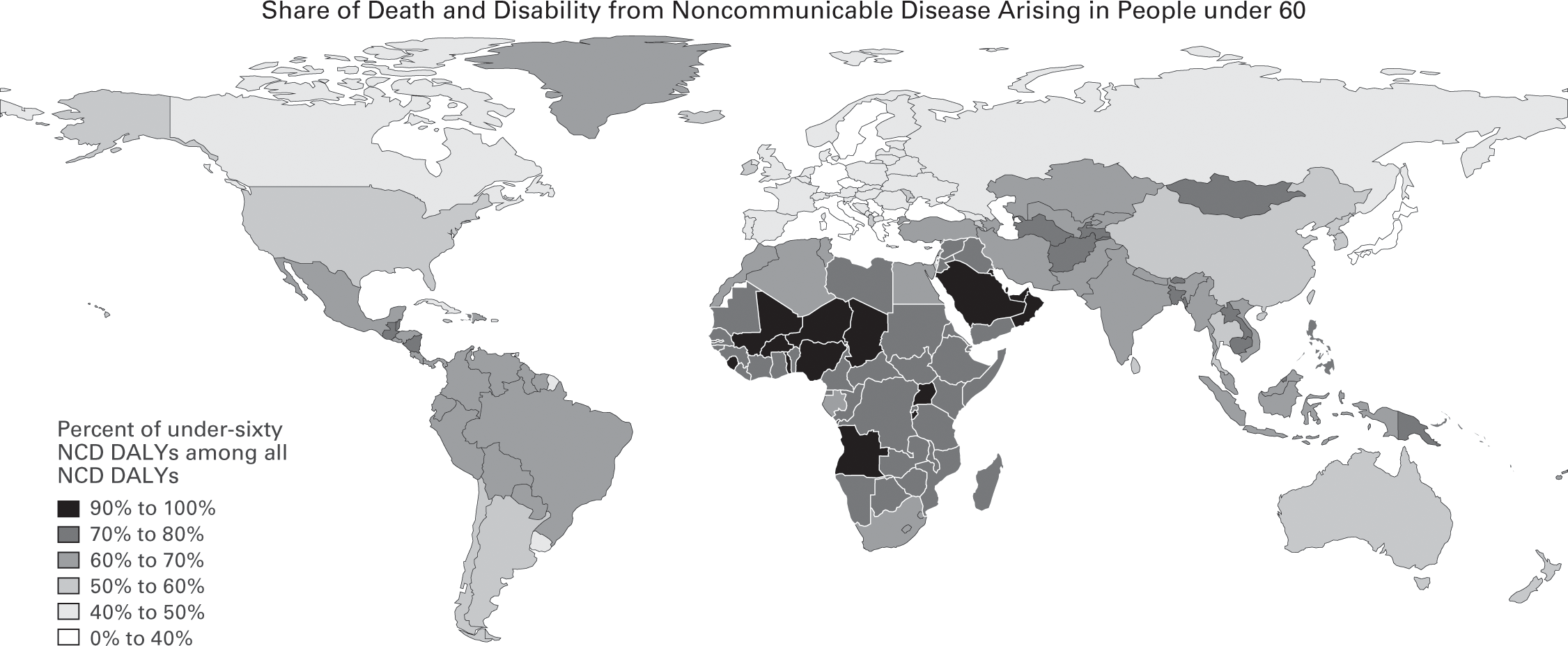

Figure 2.12

Source: Bollyky et al., Health Affairs (2017).

Reductions in plagues and parasites, however, do not explain why so many people in lower-income countries are developing these chronic ailments at much younger ages and with much worse outcomes than in wealthier nations. Premature deaths from hypertensive heart disease (in people age 59 or younger) have increased by nearly 50 percent in sub-Saharan Africa since 1990.121 The increase of premature heart disease and other chronic illnesses in developing countries is not merely the by-product of rising incomes, or adoption of unhealthy Western lifestyles. Low-income countries are, by past standards, still quite poor. When these nations, most in sub-Saharan Africa, finally achieved an average life expectancy of 60 in 2011, their median GDP per capita ($1,072) was a quarter of the wealth that the residents of high-income countries possessed when they reached that same average life-expectancy in 1947 ($4,334).122 Unhealthy habits, such as physical inactivity and consumption of fatty foods, are increasing in poor countries, but are still much rarer than in middle-income and rich nations.

The rapid increase of noncommunicable diseases in poorer countries is the by-product of the way that infectious diseases have declined in those countries. In earlier transitions, as childhood health improved, so did adult health, though at a more modest pace. Between the late eighteenth century and the start of World War I, for example, the risk of death among people over 30 years old in France decreased by roughly 25 percent.123 Adult health also advanced in the wave of developing countries that reduced infectious diseases after World War II. In contrast, there has been relatively minimal progress in the health of adults, ages 15 to 50, in those lower-income nations that have experienced more recent health transitions, other than the donor-supported reductions in deaths due to HIV/AIDS.

In fact, the gap in adult life expectancies between poor and wealthy countries has grown. A 15-year-old today in an average low-income country has the same life expectancy as a 15-year-old in that same country in 1990. Meanwhile, a teenager of the same age in a high-income country has a life expectancy of 80 years, five years longer than a similarly placed individual in 1990. That growing global disparity in adult health holds true even if one controls for HIV/AIDS.

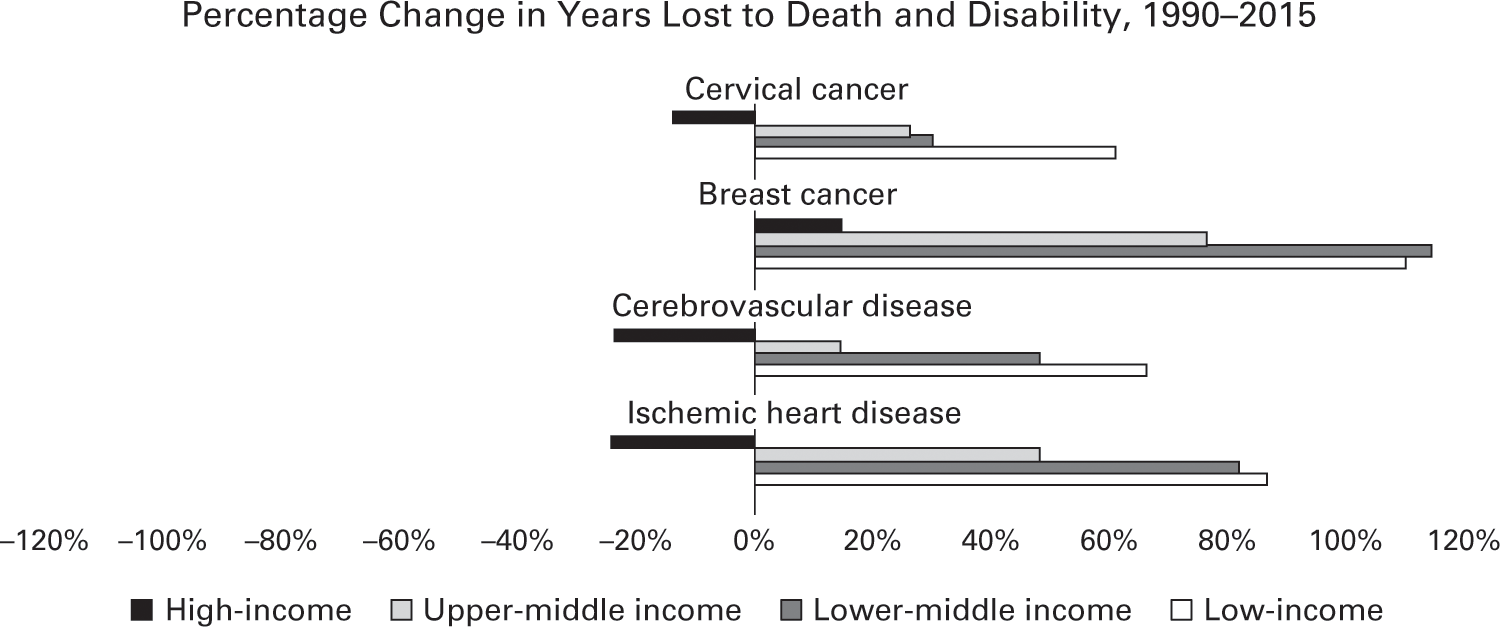

The lack of progress in adult health does not bode well for lower-income countries and their aging populations. Figure 2.13 summarizes the death and disability caused by four key diseases since 1990 by country income group. For working-age adults, the likelihood of surviving diseases like stroke (cerebrovascular disease) or cervical cancer depends on the wealth of the country where a person lives.124 The risk of early death from heart disease, diabetes, and many other noncommunicable illnesses, once known as diseases of affluence, now has a stronger statistical link to the poverty of the country than do HIV/AIDS, dengue fever, and many other infectious diseases.125

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2015.

Unfortunately, this problem will only get worse with the shifting demographics of many developing countries. The population growth in many of these nations is much faster than the rates in Europe, the United States, and other wealthy nations when infectious diseases began to decline. In those earlier transitions, population growth rarely exceeded 1 percent per year. This meant that the population of a typical European nation grew three to five times between 1750 and 1950. In the recent transitions in developing countries, population growth rates have often exceeded 2.5 or even 3 percent per year, doubling population in just a decade or two. The number of working-age adults (15 to 64) in many of these poorer countries increased by 15 percent or more every five years.126

This means that, even if mortality rates of heart disease (deaths per 1,000 people) do not get worse in many poorer nations, the number of people who survive into adulthood and are more likely to get heart disease and other noncommunicable diseases will still grow spectacularly fast.127 For example, the median age in Bangladesh, a low-income country, increased from 18 to 26 years between 1990 and 2015. Over the same time, its population increased by more than fifty percent. As a result, there are now more than 38 million additional adults between the ages of 25 and 64 in Bangladesh than there were just twenty-five years ago.128 As a result, the share of the health burden in Bangladesh due to noncommunicable diseases such as heart disease grew from 26 percent in 1990 to 61 percent in 2015. In Ethiopia, similar demographic changes have driven the noncommunicable disease burden to more than double in twenty-five years; these diseases are now expected to represent the majority of that country’s health needs in 2030. Similarly dramatic shifts are happening in other poor countries like Kenya, Myanmar, Nicaragua, and Tanzania. The transition from infectious diseases to noncommunicable ailments such as heart disease in these and other lower-income countries is occurring, and is expected to continue to occur, at a staggeringly fast rate, more rapidly than the world has ever seen before.129

Noncommunicable diseases are largely chronic and require more health-care infrastructure and trained health workers than most infectious diseases, and are more costly to treat.130 A 2013 study in Tanzania estimated that chronic diseases, like cancer and heart disease, were responsible for a quarter of the country’s health burden but nearly half of all its hospital admissions and days spent in the hospital.131 Other studies have shown that inpatient surgical procedures are used more than twice as often for noncommunicable diseases than for infectious diseases.132 Another study found that the developing countries that are experiencing the fastest transition from infectious to noncommunicable diseases are also the same nations that are least prepared for it.133 This is particularly true of most sub-Saharan African nations.

To date, neither domestic health spending nor aid budgets are filling this gap. The average government of a low-income country, such as Ethiopia, spends $23 per person annually on health. The typical government of a lower middle-income nation—India, Vietnam, or Nigeria—spends a bit more: $133 per person. In comparison, the United States spends $3,860 per person and the United Kingdom devotes $2,695 per person on health. Most aid donors are not interested in tackling chronic ailments like diabetes and heart disease.134 In 2011, the United Nations General Assembly held a high-level meeting to mobilize action to address the rising rates of noncommunicable diseases. Dozens of heads of states and thousands of NGOs came. Five years later, annual aid for noncommunicable diseases remains largely unchanged, at $475 million, which is a little over 1 percent of the aid spent each year on health worldwide.135

The situation seems poised to worsen as consumption of tobacco products, alcohol, and processed food and beverages increases in poorer nations. Supermarkets and multinational food companies have penetrated every region of the world, even rural areas.136 Access to fresh fruits and vegetables has declined, especially in East and Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.137 Between 1970 and 2000, cigarette consumption tripled in developing countries.138

Many developing countries do not yet have the basic consumer protections and public health regulations to cope with these changes.139 Many of these lower-income nations are relatively small consumer markets, and their governments have limited leverage to demand changes in the labeling and ingredients of food, alcohol, and tobacco products produced for global consumption. Large multinational corporations often have more resources than the governments that oversee them. The market capitalization of Philip Morris International at $187 billion (as of July 2017) is larger in nominal terms than the economies of most of the 180 countries where that company sells Marlboro and its other brands of cigarettes.

Figure 2.14

Man smoking a cigarette in Bangui, Central African Republic, on February 14, 2014. Photo: Fred Dufour/AFP/Getty Images.

Tobacco companies, in particular, have been especially aggressive in pursuing teens and women in poor nations, using billboards, cartoons, music sponsorships, and other marketing methods long banned in developed countries.140 When Uruguay, Togo, and Namibia proposed restrictions on cigarette advertising and labeling, multinational tobacco companies sued under trade and investment agreements to block or delay implementation.141 These tactics have helped raise tobacco sales across Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and, more recently, Africa.

With little access to preventive care and more exposure to these health risks, working-age people in sub-Saharan Africa and other lower-income nations are more likely to develop cancers, heart diseases, and other noncommunicable diseases than those in wealthy nations. Without access to chronic care and limited household resources to pay for medical treatment out of pocket, these people are also more likely to become disabled or die young.

Figure 2.15

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2015.

In sum, the biggest global health crisis in low- and middle-income countries is not the one you might think. It is not the exotic parasites, bacterial blights, and obscure tropical viruses that have long been the focus of international health initiatives and occupied media attention. In 2015 alone, the everyday diseases—cancers, heart diseases, diabetes, and other noncommunicable diseases—killed eight million people before their sixtieth birthdays in low- and middle-income countries. The World Economic Forum projects that noncommunicable diseases will inflict $21.3 trillion in losses in developing countries between 2011 and 2030—a cost that is almost equal to the total aggregate economic output ($26 trillion in constant 2010 US dollars) of these countries in 2015.

The Legacy of Ebola

There are other threats to global health that have exposed the limits of the way the world has gotten better. In December 2013, Emile Ouamouno, a two-year-old boy from Meliandou, Guinea, became ill. He had fever, vomiting, and black stools. His mother cared for the boy, but he died four days later and was buried in his village. A few days later, his mother became sick with the same symptoms and died, as did Emile’s sister two weeks later. His grandmother, also sick and understandably alarmed, sought help in Guéckédou, a nearby city with trade links to neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone. The nurse who treated her had no medical supplies and could do nothing for her. Emile’s grandmother returned to Meliandou and died. The first reports of an outbreak surfaced in late January but did not prevent the grandmother’s nurse, who also became ill, from traveling to neighboring Macenta for medical care. The nurse died there and the physician who treated him also became ill. Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) reached Guéckédou to investigate and sent samples for analysis to a laboratory in Lyon, France, which, on March 20, confirmed the deaths were caused by the Ebola virus. Later that same day, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced an outbreak was underway in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.142

The international response to the outbreak was slow. Part of the reason was that, before the 2013 outbreak, Ebola had killed fewer than 2,000 people over twenty-eight past outbreaks—all in Central Africa.143 Ebola, which was first identified in 1976, is a terrifying disease, but it does not spread easily. A person with measles, which is an airborne disease, infects eighteen other people on average; a person with Ebola, which is passed through contact with bodily fluids, infects fewer than two other people on average.144 Ebola also kills quickly in resource-poor countries, which leaves the unfortunate victim with less opportunity to spread it.

But by the time the WHO declared the end of the “public health emergency of international concern” for Ebola on March 29, 2016, the disease had killed 11,323 people and caused 28,646 confirmed cases of infection.145 The outbreak nearly spread to Nigeria after a foreign diplomat arrived ill at Lagos airport and was taken to a private hospital, where he was correctly diagnosed as having Ebola. A US CDC Emergency Operations Center working together with the Nigerian government was able to trace the nine health workers who came in contact with that official.146 Had the Ebola virus spread to the sprawling, crowded slums of Lagos, an even greater tragedy might have unfolded.

The eight cases of Ebola that did spread beyond West Africa, however, were enough to cause an international panic. Images of international health workers in cumbersome protective gear amid terrified children and grief-stricken relatives of Ebola victims in West Africa dominated nightly news broadcasts. More than a third of the flights from cities in Europe were canceled and purchases of Ebola survival kits soared in the US Midwest.147 The outbreak was a topic of debate in US congressional elections. The most recent World Bank estimates reveal that Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea lost $1.6 billion in economic output in 2015 alone, more than 12 percent of their combined GDP.148

The difference between the recent Ebola outbreak and its predecessors? Many of the same factors that are increasing the rates of noncommunicable diseases in poorer nations. With greater trade and travel to and within the region, emerging infectious diseases like Ebola are less likely to burn out in rural villages and more likely to reach the still-poor crowded cities with limited health systems that are ideal incubators for outbreaks. As with noncommunicable diseases, long-standing efforts to mobilize more donor support for pandemic preparedness went nowhere, leaving poor nations without the resources to build their capability to monitor and contain disease outbreaks.149

Starting in the mid-1990s, WHO and its member governments began revamping the global framework for responding to dangerous infectious disease events, known as the International Health Regulations. That revision granted WHO new powers, including the ability to rely on data from non-state actors and to issue scientifically grounded advice on responding to outbreaks. The revised International Health Regulations also required countries to monitor, control, and report infectious disease outbreaks. But the resources to support these functions and responsibilities have not been forthcoming.

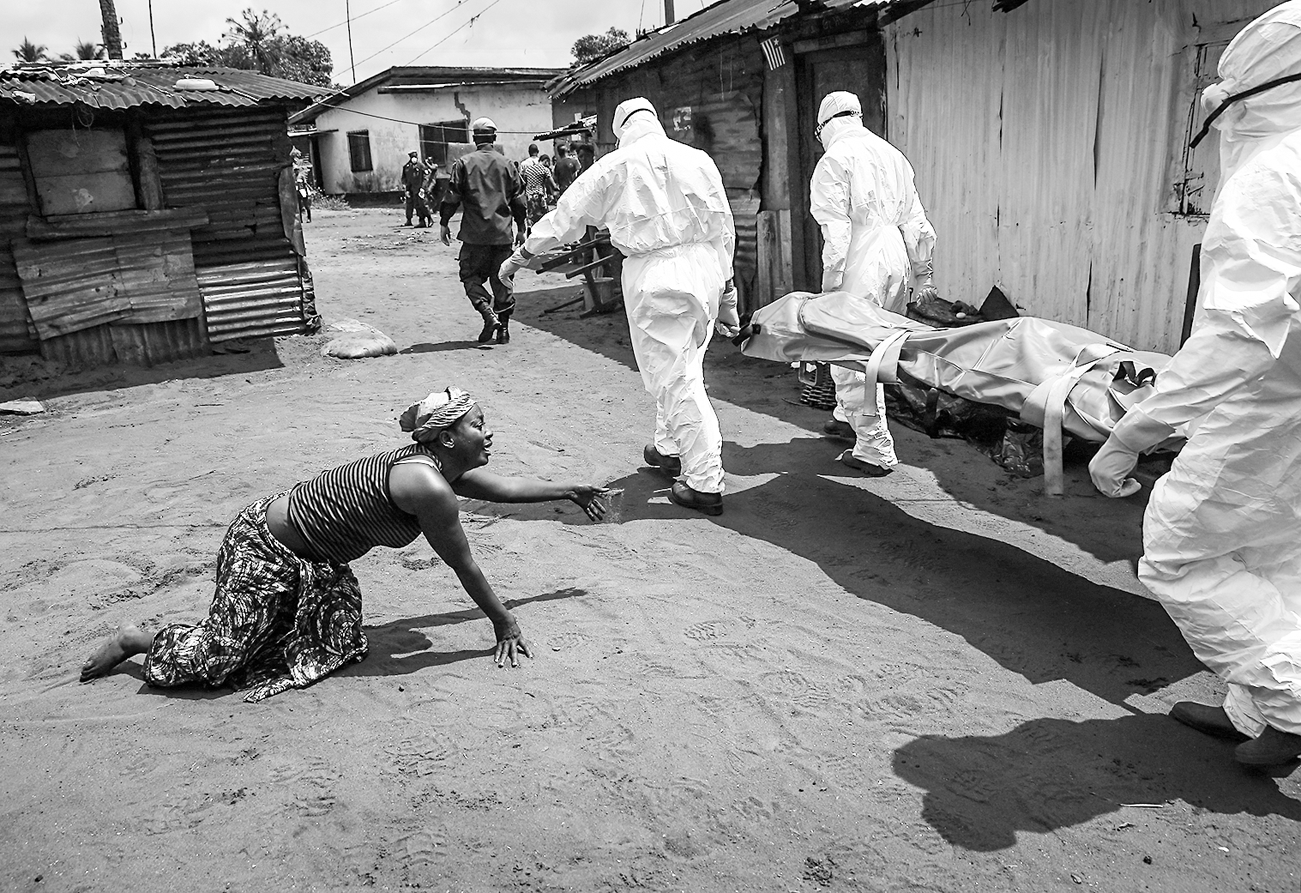

Figure 2.16

A woman crawls toward Ebola burial team members taking the body of her sister away on October 10, 2014, in Monrovia, Liberia. Photo: John Moore/Getty Images.

The portion of the WHO’s budget that is funded by dues from 194 member countries is less than the budget of the New York City Department of Health. The other voluntary contributions that WHO receives are earmarked and historically have not prioritized epidemic and pandemic preparedness in poor countries. In 2013, less than 0.5 percent of international health aid was devoted to building global response to infectious disease outbreaks.150 This has meant that pandemic preparedness has remained largely as it was in the nineteenth century—a domestic affair.

Many lower-income countries are unprepared to assume that burden or adapt to the other changes that have come with declining infectious disease rates. A third of the WHO member nations had implemented their core obligations under the International Health Regulations by 2014.151 The West African nations most affected by Ebola were not among them.

Prior to the outbreak, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone had all made commendable progress in reducing the burden of infectious disease in their countries and improving child survival, especially considering the protracted periods of war and instability in the region in the 1990s. Child mortality rates were still high, but had declined at least 33 percent in all three countries since 2002.152 Sierra Leone boosted its coverage of basic childhood immunizations from 53 percent in 2002 to 93 percent in 2012. Measles immunization rates, an indicator often cited as a basic measure of health performance, rose to 83 percent in Sierra Leone, 74 percent in Liberia, and 62 percent in Guinea. Average life expectancy had improved to 58 years in Guinea and 61 years in Liberia.153 In the decade before the Ebola outbreak, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone received nearly $1 billion from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the President’s Malaria Initiative, the World Bank, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

These donor investments saved many lives, but unfortunately did little to build capable health systems in these countries to respond to other health threats and needs. Before the Ebola outbreak, the governments of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone still spent little on health: $9, $20, and $16 per person each year, respectively. Many health services were provided by local staff of donor- and faith-based organizations and NGOs. The health workforce in these countries had grown but remained thin. Liberia had only fifty-one doctors in the whole country. Guinea had one physician for every 10,000 people. Sierra Leone had 1,017 nurses and midwives total, one for every 5,319 people in the country. The average middle-income country has ten times as many doctors and nurses; wealthy countries have thirty-seven times more.

Hospitals in these West African nations lacked basic infection-control essentials like running water, surgical gowns, and gloves. Health workers were the first to contract Ebola and die from it, further weakening health systems and leading people to avoid health facilities and to try to treat their relatives at home. In the end, volunteer health workers and burial teams from these countries performed heroically in the crisis and, with the support of the US CDC, largely saved themselves. But the costs of limited health systems were high. Outside of West Africa, only one out of eight people treated for Ebola died because those patients received basic supportive care, including intravenous fluids for rehydrating. Inside West Africa, the case fatality rate from Ebola was 40 percent.

The international system intended to control outbreaks of infectious diseases failed miserably. For the World Health Organization, the Ebola outbreak was a debacle. Leadership failures, incompetent regional and country offices, and inadequate surveillance and response capabilities undermined the agency to the point that responsibility for the outbreak was given to a UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response. Many countries ignored the International Health Regulations and imposed punitive and excessive trade and travel restrictions on West African nations. Jérôme Oberreit, the secretary general of Doctors Without Borders, said “it has become alarmingly evident that there is no functioning global response mechanism to a potential pandemic in countries with fragile health systems.”154

Margaret Chan, the former Director-General of the World Health Organization, implored countries “to turn the 2014 Ebola crisis into an opportunity to build a stronger system to defend our collective global health security.” Forty-five separate expert assessments were published about the Ebola crisis and their recommendations were largely the same: institutional reform and more funding for the World Health Organization, together with greater investment in epidemic and pandemic surveillance, preparedness, and response in poorer countries.155

Important measures have been undertaken to prepare for the next outbreak, most following the same script as past global health initiatives. A new initiative to develop vaccines for future epidemics is well organized and well funded, with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the governments of Norway, Japan, and Germany.156 As of April 2017, twenty-one lower-income nations had participated in external evaluations of what they need to do to prevent human and animal disease outbreaks, but only three had begun implementing the results. After the Ebola outbreak, the United States dedicated $1 billion to help poor countries build the basic capabilities to prevent, detect, and respond to pandemic threats, but that important program is poised to expire in 2019 and US funding for pandemic preparedness will sink to its lowest level in a decade. The World Health Organization has been unable to attract much donor support for its new response system and the agency has yet to implement many of the deep institutional reforms recommended after the crisis.157

An outbreak of the Zika virus in 2015 provided an early test of this system and the apathetic global response bodes poorly for future global health emergencies.158 Several years after the Ebola outbreak, coordination and funding of international epidemic and pandemic preparedness and response remain ad hoc and dependent on media attention. “We still are not ready for the big one,” said Ron Klain, the former US Ebola czar, to the Washington Post in October 2017. “We’re frankly not ready for a medium-sized one. The threat is still out there.”159 Much of the opportunity that the Ebola crisis provided for enhancing global health security may have been squandered.

The Difference That Health Aid Makes

In recent years, an active debate has emerged over the effectiveness of foreign aid. The economist Bill Easterly and others have observed that substantial amounts of aid have not made countries like Haiti any less poor.160 Foreign aid has also been criticized for making recipient nations the dependent, neo-colonial wards of donors (by economist Dambisa Moyo) or even propping up dictatorships (by Bill Easterly, again).161 These are fair concerns and worthy of the debate they have received.

But viewed from ground level, in places like the Ethiopian countryside, the answer to the question of whether foreign aid has worked to improve health is simpler. Of course it has, and on infectious diseases, often spectacularly so. As figure 2.17 shows, every one of the diseases that international aid initiatives have targeted, from HIV/AIDS to malaria to newborn disorders, has declined dramatically in Ethiopia.

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2015.

That progress against these infectious diseases has deeply reduced the number of deaths of Ethiopian children under the age of five. Those reductions also happened much faster than would be expected based on the improvements in the country’s level of income, education, and total fertility rate, as figure 2.18 demonstrates.

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2015.

Most global health programs were not designed to establish primary care or public health systems, and they have succeeded in not establishing them. Many poorer countries have been slow to invest in their own health systems. That lack of investment in primary, preventative, and chronic health care in lower-income nations has left many of their citizens exposed to emerging threats like Ebola and the surge in everyday noncommunicable diseases. Greater dependence on donor-driven reductions in infectious diseases may also mean that these microbial threats are not playing the same role in forcing nations to invest in capable public health systems and responsive governments as these diseases did in the past.162

Inspired by the example of China, Ethiopia has hired and trained 38,000 community health workers to promote preventative health care in rural areas, which has improved child survival and lowered maternal deaths. The Ethiopian government, which is dominated by an ethnic minority group, has emphasized these community workers and the country’s improved health performance as a way to build its national legitimacy and popular support.163

Nonetheless, so much of the recent health-related gains in Ethiopia was dependent on foreign aid. The country is the largest recipient of health and development aid in sub-Saharan Africa, at $3.9 billion per year.164 Between 2012 and 2014, the United States spent $660 million on antiretroviral therapy and associated services for the 380,000 Ethiopians living with HIV. Between 2003 and 2009, Ethiopia also received roughly $3.2 billion in health support from the Global Fund and $70 million from the World Bank.165 In contrast, Ethiopia spends less than 1 percent of its own domestic health budget on HIV.166 Indeed, the Ethiopian government spends less overall on health per capita than its neighbors in the region.167 Ethiopia devotes little of that small health budget to conditions that have not attracted donor attention. An independent assessment found that the country’s health workforce suffers from a lack of professionalism and that doctors and nurses were so scarce in some hospitals that admitted patients often received care from their visiting relatives.168