4. A Growing World, 1920–30

The skies over southern Brooklyn were overcast on Saturday, May 1, 1920, which put a damper on the massive crowds that were expected at Coney Island that day. Still, a new era dawned that morning at “the people’s playground.” Nothing had changed on the island itself: the two huge amusement parks, Luna and Steeplechase, still stood like siren sisters luring city residents to the ocean; the miles of beach still offered what felt like unlimited outdoor space to those who dwelled in New York’s cramped tenement apartments; and the hundreds of saloons, bathhouses, hotels, tattoo parlors, music halls, dime museums, and other attractions still served hedonism in as many flavors as the mind could dream up.

But something more profound and less visible had changed, transforming Coney Island overnight into “the Nickel Empire.” After protracted wrangling between various companies and city agencies, the price of a subway ride to Coney Island was finally lowered from ten cents to five, the same amount it cost to go to any other station in the rapidly expanding subway system. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle crowed that a new “epoch in the history of transit in Brooklyn was starting.”1 By the end of June, the Eagle would announce that some 350,000 New Yorkers had visited Coney Island on one particularly nice Saturday.2 In August, 450,000 would arrive in one day.3 And the numbers kept climbing; at particularly busy times over the next few years, “as many as a million people poured in during a single day,” meaning that about a third of the city’s entire population could be found somewhere on Coney Island’s meager 442 acres.4 By the end of the decade, Clark Kinnaird would use his nationally syndicated Diary of a New Yorker column to bash Coney Island for its overcrowding, writing, “It isn’t news unless half a million pack into the series of amusement parks which comprise ‘Coney,’ and at least 50 children are lost.”5

The nickel fare accelerated both growth and change at Coney Island. Originally it was a distant seaside excursion spot for the city’s elite, but as Brooklyn became more navigable in the late 1800s, New Yorkers of all classes rushed to enjoy its salt breezes and sandy beaches. However, much as in downtown Brooklyn, the first working- and middle-class venues, such as the joints where Florence Hines performed, primarily served white men. Coney wouldn’t be a beacon for all New Yorkers until the very end of the nineteenth century. In 1897, George Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park, the first of the island’s iconic amusement parks. Luna Park was built next, in 1903, and Dreamland appeared in 1904 (only to disappear in a tragic fire in 1911). These parks featured exciting new automated technology, vast rainbows of electric lights, roller coasters, tunnels of love, a profusion of new foods, and, perhaps most important, a social opportunity that men and women could enjoy together. The parks consciously catered to middle- and working-class consumers, marketing themselves as “family-friendly” areas where people of all classes, ethnicities, and races could mix, while not being far removed from the “freer sexual expression of the dance halls, beaches, and boardwalk.”6 In 1919, the construction of the West End Terminal—a massive train depot capable of handling the hundreds of thousands of passengers from the four subway lines that began serving Coney Island in the 1910s—set the stage for Coney’s busiest era, which coincided neatly with the Roaring Twenties. World War I was over, and Americans were ready to celebrate. Coney Island, where cheap pleasures reigned supreme, was the place to do so.

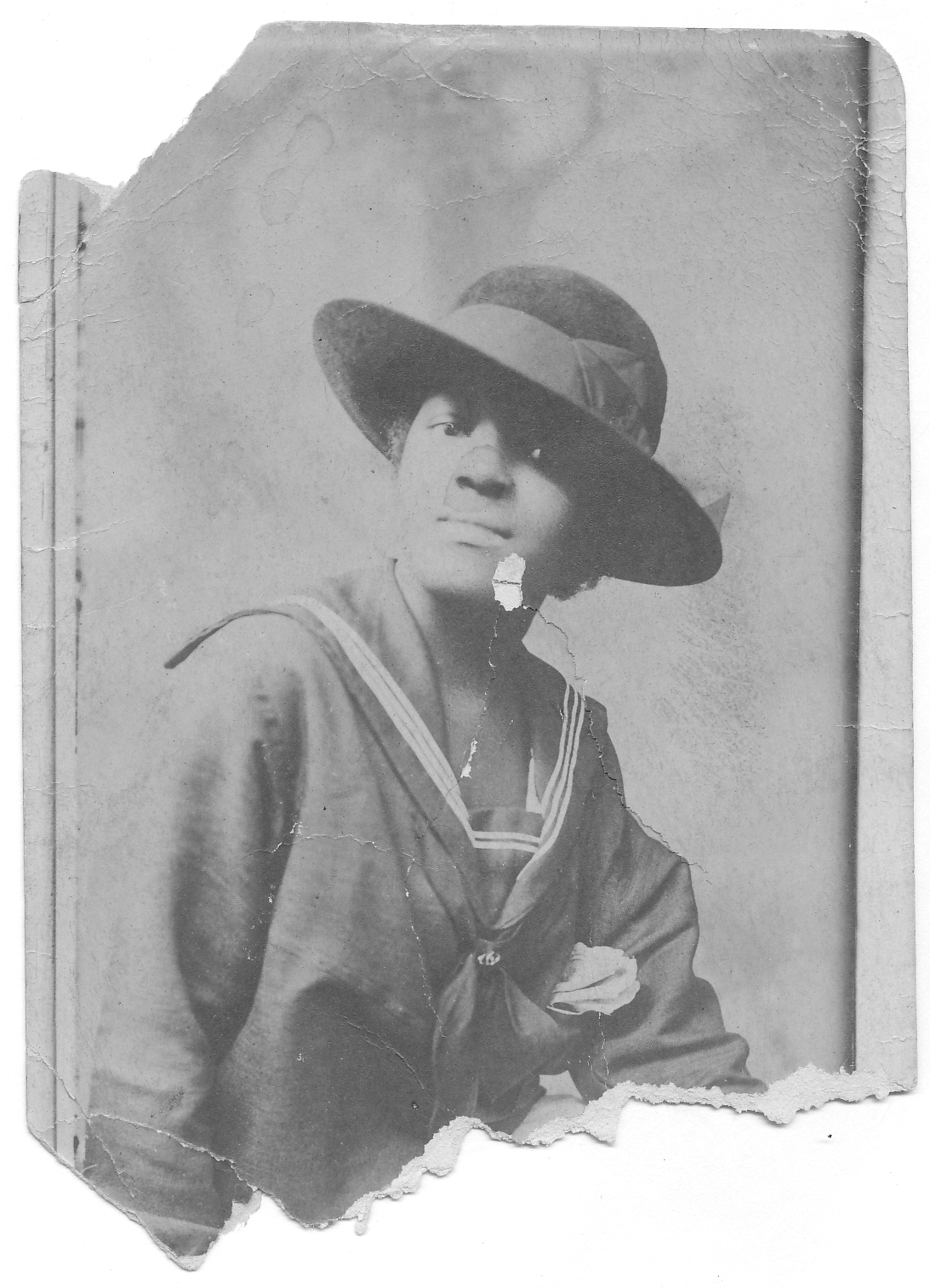

Portrait of dancer Mabel Hampton (c.1920). (Photo courtesy of the Lesbian Herstory Educational Foundation, Mabel Hampton Collection.)

On May 2, 1920—one day after the new fare was inaugurated—Mabel Hampton turned seventeen. Hampton was petite, pretty, and originally from North Carolina. Shortly after she was born, her mother died under suspicious circumstances, and Hampton was raised by her grandmother. When she died in 1910, the then seven-year-old Hampton was sent north to live with an aunt and uncle in Manhattan, where she would become an entertainer and fixture in the burgeoning queer scenes developing in Harlem, Greenwich Village, and Coney Island. In many ways, her experiences are emblematic of the best parts of the Roaring Twenties, at least in regard to queer life in New York City.

Hampton was an early part of a nationwide demographic shift called the Great Migration. After Reconstruction, Southern black communities saw most of the meager power they had gained post–Civil War destroyed by the imposition of Jim Crow laws. In response, many headed North and West looking for better jobs and living conditions. According to Kevin Mumford, author of Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century, “between 1910 and 1920 the black population of New York increased by 66 percent, and from 1920 to 1930 it expanded by 115 percent, from roughly 153,000 to more than 327,000 black residents.”7 From this point on, the black population in New York City would increase steadily, giving rise to the Harlem Renaissance and the image of the New Negro: empowered, educated, and dedicated to the black community. At the start of the 1920s, Brooklyn’s population was still more than 98 percent white, and it would remain significantly whiter than Manhattan until the 1970s. However, the changing racial and ethnic composition of the city as a whole meant that vastly more people of color were now traveling through Brooklyn regularly—many of them, like Mabel Hampton, on their way to Coney Island.

Like many migrant girls, Hampton had a difficult time upon first arriving in New York. Her aunt and uncle were poor, and her uncle sexually and physically abused Hampton repeatedly. Not long after she arrived, at the age of eight, Hampton ran away. Not knowing where to go, she let the flow of the crowds in Greenwich Village lead her to the subway, which she’d never before seen. A friendly older woman, mistaking her for the daughter of an acquaintance, gave Hampton a nickel and told her to go home to Harlem, which was just becoming the fast-beating heart of the city’s black community. Hampton got on the first train that came and eventually found herself across the Hudson River in Jersey City, where she was taken in by a working-class black family in a mixed neighborhood. Hampton feigned ignorance of everything—where she was from, her last name, where her aunt and uncle could be found—and eventually this new family adopted her. She would stay in Jersey City with them until right around 1920, when she would begin doing domestic work for Manhattan families.

Seventeen, making her own money, and living on and off in Harlem, before long Hampton found her way to Coney Island, which changed her life forever. As she recalled many years later while being interviewed by Joan Nestle and Deb Edel, the founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives:

The making of me? It’s that one woman in Coney Island. I can’t right now recall her name, but she is the beginning of me being a lesbian. I was no more than about seventeen, eighteen years old. I fell in love with her. I didn’t know I fell in love, but I did.8

The hours of taped interviews between Hampton, Nestle, and Edel are an unparalleled archive of information about queer women in early-twentieth-century New York. Nestle and Edel began recording Hampton in the late seventies and continued almost up until her death in 1989. The resulting tapes contain a unique, wide-ranging, and occasionally contradictory wealth of information for historians interested in black lesbian life. While Hampton’s experiences cannot stand in for all black queer women in New York City, the wide-ranging world she describes hints at the multiplicity of lives these women made for themselves (and with one another).

The first time she visited Coney, Hampton was living in a three-room basement apartment in Harlem with a friend named Mildred Mitchell and her mother, Miss Mitchell. Mildred was a dancer, and she had the idea that the two should get work performing in a sideshow. Miss Mitchell, eager to keep an eye on the two young girls, joined the show as a cook. The troupe consisted of between six and fifteen other black women who wore “velvet suits,” did choreographed dance routines, and sang popular songs of the day. Hampton recalled that she sang the 1922 hit song “My Buddy.” In photographs, the troupe is pictured rehearsing on the beach in front of Henderson’s Music Hall, an elegant and storied Coney Island venue that was then on its last legs. It’s possible they performed there, as its stage was home to many cabarets and concerts, but Hampton never specified a venue, saying only that she danced “in the sideshow.”

The troupe must have performed during the day; Hampton recalled that they ate breakfast together, and that most nights she took the subway home around 6:00 p.m. One evening during their supper, she noticed a “tall, light-brown-skinned woman … [who] had to have been in her thirties.”9 The woman was visiting with a group of Mildred’s friends from “somewhere West.” Throughout dinner, the two made eyes at each other, although Hampton looked away every time she realized the woman knew she was watching. Hampton had fooled around with other women before, mostly friends with whom she was living, but this was different. “Her look shot through me like electricity,” Hampton later told Joan Nestle.

Over breakfast the next morning, the eye games continued—so much so that Miss Mitchell even noticed. “I tried to keep my eyes off her, but she was like a magnet,” Hampton recalled. After breakfast, the woman intercepted Hampton and invited her to go on a walk when rehearsal was over.

Once they were alone, the woman wasted no time. “When I look at you, it thrills you, don’t it?”

Hampton blushed and stammered, “Yes, I think so.”

“That’s all right,” the woman said kindly. “You can’t help with that. But I have to go so I don’t ruin your life.… I’m a lesbian, and I’m married.”

That was the moment, Hampton says, when she learned the word lesbian. “I said to myself, ‘Well, if that’s what it is, I’m already in it!’” Never one to be easily dissuaded, Hampton convinced the woman that while she might be young, she knew what she wanted. So she asked Miss Mitchell, Mildred’s mother, if she could spend the night with her new acquaintance.

Miss Mitchell looked appraisingly at the woman. “She knew exactly what it was,” Hampton told Nestle years later. In part, Hampton suspected this was because Miss Mitchell also knew that Hampton and Mildred occasionally fooled around. Miss Mitchell made the woman swear that she wouldn’t “mess up Mabel,” then gave the pair her blessing.10

Of her one night with this mysterious older woman, Hampton would say only, “She taught me quite a few things. I knew some of them, but she taught me the rest.”11 The next morning, the woman announced over breakfast that she had to return home. Already, she seemed worried that she had broken her promise to Miss Mitchell, that she had inculcated something in Hampton that would ruin her. But Hampton is clear on the tapes that the woman only helped her to name and understand feelings she already had.

Over the twentieth century, “coming out” to an older, wiser queer person would become one of the defining experiences of being queer. The phrase coming out is derived from debutante culture, and it once referred exclusively to being brought out into gay society (as opposed to our modern usage, which is more about proclaiming your sexual identity to the straight world). But Hampton’s generation is the first group for whom this experience was widely possible. For the first time, queer people such as Hampton had an avuncular older generation to educate them, and a younger generation to preserve and pass on their stories. This represents a new stage in queer history. First, individual queer people kept their own stories, often privately or in code. Then, the larger straight world began to write about queer lives, often pejoratively and in limited venues that presented them as anomalies to be studied. Now, a wider community of queer people were beginning to share their experiences with one another and preserve them for future generations. This changed not just the quantity of available information, but the quality, enabling historians to get a closer, more personal understanding of what it meant to be queer in these times.

Hampton met many other queer women, black and white, married and single, while she worked at Coney Island. Once, a married black woman took Hampton home in the middle of the day, only to have her husband arrive unexpectedly. Hampton was forced to hide under the bed while he peppered his wife with questions as to why she was home—and naked—in the middle of the afternoon. Eventually, when the pair went downstairs to make lunch, Hampton grabbed her clothes and sneaked out through a side door.

Slowly, Hampton settled into the role of stud, a popular term among queer black women that was analogous to being the butch in a butch-femme couple. “You had to be very careful,” she recalled. “In those years you had fun behind closed doors, but you’d go like you were going to work.” She and other studs would bring suitcases to parties so they could change into trousers when they arrived—it would have been too dangerous, Hampton said, to dress that way on the streets. Although many women did not identify as either a butch or a femme, and some moved between the two roles throughout their lives, the butch-femme paradigm in lesbian relationships would become dominant in the years leading up to World War II.

Yet despite the need for subterfuge, Hampton was tapped into a large lesbian network. “I had so many different girlfriends it wasn’t funny,” she told Nestle and Edel. Throughout the Roaring Twenties and into the early thirties, Hampton said, “You’d go out, have a ball, spend the night somewhere, and have another ball.” Her circle of friends was almost exclusively lesbian and bisexual women, though she occasionally befriended queer men at parties. Much as Walt Whitman serves as an indicator of the existence of queer white working-class men in Brooklyn in the mid-1800s, Hampton’s oral history suggests large, parallel networks of white and black queer women, which sometimes overlapped. Her queer life was expansive, happening all around New York and even out in Jersey City, but the three main centers of action were Harlem, Greenwich Village, and Coney Island. While most of the black lesbians Hampton knew had at-home parties (often called buffet flats) up in Harlem, the white women were more likely to go to bars or clubs—often down in Greenwich Village—that were lesbian owned or lesbian friendly. “White folks can get into places where you can’t,” Hampton told Nestle during her interviews. “They’d take me to nice clubs and I’d meet all the women I wanted to meet.”12

In Harlem, Hampton was quickly immersed in the world of A’Lelia Walker, the glamorous patron of many of the queer voices of the Harlem Renaissance, whom Langston Hughes dubbed “the joy goddess of Harlem.”13 Walker was the daughter of Madam C. J. Walker, who was born in Louisiana in 1867, just after the end of the Civil War. The first freeborn child in a formerly enslaved family, Madam Walker founded an incredible business empire selling hair and skin products for black women. By the early 1900s, she was the richest black woman in America. Her daughter, A’Lelia, was her only heir, and while never the business genius that her mother was, A’Lelia was the recognized queen of Harlem’s bohemian scene. Over six feet tall and strikingly handsome, A’Lelia often strode the streets of Sugar Hill carrying a riding crop and wearing a bejeweled turban.14 She named her home on West 136th Street the Dark Tower, after the poem of the same name by Countee Cullen, a queer black poet to whom Walker served as a patron. Her parties were epic, as likely to include visiting Scandinavian royalty as they were a bootlegger from Vinegar Hill. The first time Mabel Hampton went, she was ushered through a warren of rooms by a butler, who instructed her to remove her gray sheath dress and short white fur coat, before bringing her and her girlfriend to a sumptuous ballroom filled with pillows, low tables bearing fruit and wine, and dozens of nude or nearly nude partygoers. As Hampton described the night to Joan Nestle and Deb Edel:

There was men and women, women and women, and men and men. And they were all on the pillows and [if] they wanted to do anything, they go ahead and do it. Then—now, you’d call it dope, but I didn’t realize what it was then.… So we had a lovely time. Stayed all night. Until three or four the next day. And everyone did whatever they wanted to do. Some of them did one thing and some of them did the other thing. Nobody paid anybody else any attention.… There was girls there with no clothes on. They served me with food. It was marvelous.15

On other nights, Hampton socialized in the burgeoning (white) queer public scene miles to the south of Harlem, in Greenwich Village. The first official spot run by and for queer women in New York City was Eve Addams’ Tea Room, which opened in 1925 on MacDougal Street. A sign on the front door read MEN ARE ADMITTED, BUT NOT WELCOME. It lasted only a year before its owner, Polish immigrant Eva Kotchever, was arrested for obscenity and keeping a disorderly house and eventually deported. But other spots catering to queer women would appear in the late twenties and thirties, many of them literally in the shadows—beneath the elevated trains, which ran through lower Manhattan. Gay bars catering to men also appeared around the same time, some up by Times Square, while others were also downtown under the elevated trains. At the same time that the nickel fare was inaugurated, Prohibition was enacted, with profound although unexpected long-term effects on gay bars. By making all bars illegal, and all bar patrons criminals, it leveled the playing field between queer and straight venues. For the same reason, Prohibition also helped normalize the presence of women in most drinking establishments. The criminalization of the recreational choices of straight white men—which made their establishments just as subject to raids as those that catered to queers or sex workers—helped queer and queer-friendly venues proliferate throughout New York City in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The enacting of Prohibition also cut the legs out from groups such as the Committee of Fourteen, in two ways: because they had “succeeded” in outlawing alcohol, they found it harder to raise money for their work, and because public saloons had transformed into hidden speakeasies, that work had become all the harder to do.

Later in the twenties, Hampton left Coney behind for bigger, better-known stages. She performed at such venerable institutions as the Garden of Joy and the Lafayette Theater, which were central to the booming black art scene at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance. She befriended some of the crème de la crème of the city’s queer black society, including comedian Jackie “Moms” Mabley, entertainer Gladys Bentley, and the singer Ethel Waters and her girlfriend, dancer Ethel Williams. Although Hampton never lived in Brooklyn, her life shows the intimate connections that existed between queer worlds in different parts of the city. The subway that made Coney Island more accessible also made the entire city smaller, closer, and more interconnected. Harlem, just as much as Coney Island, would be transformed by it. The combination of a growing black population and available, easy transportation turned Harlem into both the biggest black neighborhood and the hottest nightlife destination in the city. According to Kevin Mumford, “Before the late 1910s Harlem was neither a popular nightspot nor a common destination of tourism; even among New Yorkers it was not notable in the ways that Times Square or Broadway had become.”16 Over the 1920s, however, it would become known for its drag balls, jazz clubs, and speakeasies. Many venues catered to black New Yorkers; others, to rich white New Yorkers who were interested in “slumming”; and a few provided legitimately mixed space where black and white patrons mingled. Although Coney Island helped Hampton start her life as both a lesbian and a performer, she would spend most of her time in Harlem.

Life in the theater wasn’t all parties and sunshine. Hampton didn’t love dancing, she says on the tapes; it was simply a job that was available to her as a young black woman with an eighth-grade education. Most of the other queer women she knew worked either in factories or in show business. The money was never great, and sexual abuse at the hands of club owners and patrons was common. “Every place I worked,” Hampton told Nestle, “some man would feel my pussy and I’d have to leave that job.”17

In 1924, a few years after she started dancing at Coney Island, Hampton was arrested in a “setup” for prostitution and sent to the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women—the same institution where Elizabeth Trondle had been sent a few years earlier. This was a not-uncommon experience for black women in New York City. Not only were they prejudged as more criminal and sexual than their white counterparts, but their higher rates of employment and the greater gender imbalance in the black population also meant that they were more likely to be out on the streets unaccompanied by men. To groups such as the police and the Committee of Fourteen, those facts alone were enough to arrest a woman for prostitution. As historian LaShawn Harris wrote in her book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy, “Whether strolling city streets with friends, visiting a relative’s apartment, renting rooms to boarders, or operating legitimate businesses, black women faced police harassment and were arrested and convicted for a number of crimes, including possession of numbers slips, loitering and vagrancy, and prostitution.”18 Black lesbians, who were even less likely to be accompanied by men than black straight women, were at even greater danger for this kind of police abuse.

According to Hampton, she and her friend Viola met a man at a cabaret who bought them a soda and offered to treat them to a night out. Most likely, he was a police informant; when he arrived to pick them up at the apartment in Harlem where Hampton was working as a live-in domestic, the police were right behind him. From the very beginning, even in her statements to the social workers at Bedford Hills, Hampton maintained that she was framed. Thanks to the low legal bar in prostitution cases (established by the Committee of Fourteen), Hampton was convicted on thin evidence and sentenced to three years in Bedford Hills. The magistrate in her case, Judge Jean Norris, was the first female magistrate in New York City history, and she was known to judge both prostitution cases, and cases involving black women, harshly. In over five thousand cases, and especially in prostitution-related arrests of black women, Norris handed down 40 percent more convictions than other magistrates.19 Eventually, she would be removed from office for her prejudicial rulings. However, the discrimination black women faced in the legal system in New York went far beyond one bad apple. According to Cheryl Hicks, author of Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935, compared to convicted white women, black women were less likely to receive probation, were accepted by fewer of the charity homes that took in troubled women, and were—like Mabel Hampton—more likely to be sent straight to Bedford Hills on their first arrest.

Both New York City and the country as a whole were becoming much more interconnected, meaning that more black women, such as Mabel Hampton, were in the city, spending all or part of their days outside of predominantly black neighborhoods—a vulnerable and precarious situation that made them easy targets for the police. White reform organizations such as the Committee of Fourteen were unperturbed by the disproportionate arrests and convictions of black women. In discussing prostitution arrests in an internal bulletin dated June 5, 1922, the committee wrote, “The high proportion of convictions of negroes was not unanticipated … [and] the proportion of negro defendants, is … four times the proper proportion.”20 No efforts to investigate or change these statistics were suggested or pursued, leaving black women with few sources of support inside the criminal justice system. Black women’s reform organizations, such as the White Rose Mission in Harlem (where Alice Dunbar Nelson had volunteered in the 1890s), offered some assistance, but lacked the funding to help the many young black women who needed their services. Moreover, many of these organizations worked under a theory of racial uplift and judged working-class and criminally involved black women harshly. Some saw these women as holding back the entire race, while others took a paternalistic view that reduced poor black women to near children who could not be trusted to make good life choices. A black lesbian dancer, arrested for prostitution, did not make an obvious candidate for their help.

While queer black women were thus often at the mercy of a justiceless justice system, they also found ways to use that system to their benefit. Hampton was adept at marshaling the resources available to her through Bedford Hills. Her case files show that she quickly befriended both residents and staff and was considered a model inmate. After being released early on a work program, she voluntarily returned to Bedford because the conditions she was working under were exploitative and the family was impossible to please. A few months later, in 1927, Hampton was released from Bedford for good. However, she still found ways to use her connection to Bedford to her advantage. When a white family refused to pay her an appropriate wage, she got the staff of Bedford Hills to intercede on her behalf and demand a raise.

Although she was somewhat loath to discuss it on tape, Hampton had sexual relationships with several other residents during her time at Bedford. The staff were well aware that some of the girls in their care were romantically and sexually entangled; they worried mostly about young white women pursuing young black women. This relatively open approach to same-sex sexuality was most likely due to the first director of the institution, a lesbian reformer and sex researcher named Katharine Bement Davis. In 1929, Davis would publish a remarkable study on the sex lives of women. Out of 1,200 college-educated participants, Davis found that 605 had “intense emotional relations” with other women. For 234 of those women, the relationship included mutual masturbation or “other physical expressions recognized as sexual.” For an additional 78, those relationships were not physical, but the women in them recognized them “as sexual in character” while they were happening.21 Put more plainly, over a quarter of the women Davis interviewed admitted to having relationships with other women that were sexual in nature, if not always in deed. Although Davis left Bedford before Hampton arrived, her modern attitude toward sexuality permeated the administrative culture, creating a surprisingly open space for exploring lesbian desire.

After leaving Bedford for good in 1927, Hampton mostly stopped performing. That year, she sang “My Buddy” in the funeral procession for Florence Mills, the black cabaret star known as the Queen of Happiness. But within a few years, she began primarily relying on domestic work for her income and would for the rest of her life. Even after she stopped performing, however, Coney Island remained a popular destination with Hampton and her circle of queer women. “We’d hang out, go out on the beach … under the boardwalk, we’d have a ball!”22 In 1932, she met the love of her life, Lillian Foster, and they remained together until Lillian’s death in 1978. We know all of this thanks to Hampton’s constant cultivation of a circle of queer women, and thus it’s no surprise that she was an integral part of the founding of the Lesbian Herstory Archives in 1974. A decade later, in 1984, Hampton addressed the crowds at New York City’s LGBT Pride Parade to say:

I, Mabel Hampton, have been a lesbian all my life, for eighty-two years, and I am proud of myself and my people. I would like all my people to be free in this country and all over the world, my gay people and my black people.23

The next year, at the age of eighty-three, Mabel Hampton’s decades of organizing were recognized when she was named grand marshal of the New York City Pride Parade. Four years later, while living with Joan Nestle, she died of pneumonia. Her papers and effects are preserved at the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

Hampton’s experience shows how Coney Island’s sexually charged atmosphere allowed for the exploration of queer desires. But one aspect of Coney was queer by design: the freak shows, where gender-nonconforming and intersex people were both celebrated and exploited. Bearded women were among the most common of these performers, but other acts also explicitly played with gender, such as “half-and-halfs,” who were said to be half-man, half-woman, and “animal girls” or “missing links,” which is what bearded women of color were called. According to Ward Hall, a gay man who got his start in the circus in the early 1940s, these acts were sometimes performed by people who were actually intersex, but they were also done by effeminate men and masculine women whose gender presentations were already so at odds with what the audience expected that they believed them to be physically intersex as well.

By at least the late 1800s, bearded women were performing at Coney Island. Madame Myers, known as the “queen of the bearded ladies,” toured the United States with a number of different sideshows between 1870 and 1910, and Coney Island was one of her regular stops. She would have been but one of the many acts, including Ella Wesner and Florence Hines, who were making a living by exposing Americans to the wide world of gender variance. According to an article written in 1879, Myers was “a handsome girl” of twenty-five, whose beard began to grow after the birth of her first child, when she was seventeen.24 Her contemporaries, who also performed on and off at Coney, included Annie Jones, Miss Leo Hernandez (aka the Spanish Bearded Lady), and Madame Lyons.

Unfortunately, little is known about most of these women. Many changed their names when they joined the circus, then changed them again when their routine had grown stale and they wanted to reinvent themselves. Little of their personal lives was ever documented, and what information does exist usually comes from their professional biographies, which were designed to titillate audiences and are highly suspect. Jean Carroll, for example, made her life in the sideshow by selling a pamphlet entitled “How I Became the Tattoo Queen,” which explained that she had once been the bearded woman at Coney Island, but had shaved for the love of a man who would not marry her otherwise. In love with the circus—and having no other way to support herself—Carroll became the tattooed woman, a role she would perform on and off at Coney Island up until the 1960s. However, while there is ample evidence that Carroll worked as a tattooed woman, there’s no evidence that she ever had a beard.25 Tattooed women were considered so strange and unfeminine that they usually invented these kinds of elaborate backstories to entertain their audiences and explain their origins.

One Coney Island bearded woman whose life was relatively well documented, however, was Lady Olga Roderick—aka Jane Barnell, from Wilmington, North Carolina. Her story shows the complicated life of exploitation and empowerment that many freaks (her preferred word) experienced in the sideshow. Born in 1871, Barnell said that she began growing a beard at the age of two and was sold to the circus by her mother at the age of four. A year later, she was rescued by her father and returned to North Carolina to live with her grandmother, who was Catawban (a small part of the much-larger Sioux Nation). At age twenty-one, she returned to circus work, launching a spectacular career that spanned some six decades.

Coney Island bearded lady Jane Barnell and husband, date unknown. (Photo courtesy of the collection of David Denholtz.)

According to Edo McCullough, author of Good Old Coney Island, Barnell was “the most celebrated” and “widely traveled” bearded woman of her day. Barnell had many names and backstories in her career, but her favorite way to be introduced was:

It gives me great pleasure at this time to introduce a little woman who comes to us from an aristocratic plantation in the Old South and who is recognized by the finest doctors, physicians, and medical men as the foremost unquestioned and authentic female Bearded Lady in medical history. Ladies and gentlemen, Lady Olga!26

McCullough places Barnell at Coney Island starting in the 1930s, but she was actually performing there at least as early as 1926, the year Zip the Pinhead died. Zip was one of the most famous sideshow performers of all time, and accounts of his death and burial include Lady Olga among the other performers with him at Coney Island.27

How do we know so much about Barnell? In 1932, Barnell was cast in the cult horror film Freaks, which made her a national sensation. Newspapers around the country reported on her beauty tips for women with beards, which included “never use too hot a curling iron,” “wash the beard in warm milk once a week,” and “avoid eating Chinese noodles.”28 Almost a decade later, in 1940, Barnell would again capture the public’s interest, when writer Joseph Mitchell profiled her for The New Yorker.

According to Mitchell, Barnell liked working at Coney Island a little better than she did most places because “that salt air is good for her asthma” and “she has a high regard for the buttered roasting ear corn that is sold in stands down there.”29 As with most coverage of bearded women, Mitchell made a big deal of Barnell’s four marriages. Reporters and managers often went to great pains to establish the heterosexuality and femininity of bearded women, as a way to contain their gender nonconformity and render them less threatening or “queer.” However, Barnell herself seemed to have no interest in letting viewers into her personal life. Mitchell describes Barnell’s usual turn on the sideshow platform thusly:

Miss Barnell is rather austere. To discourage people from getting familiar, she never smiles. She dresses conservatively, usually wearing a plain black evening gown. “I like nice clothes, but there’s no use wasting money,” she says. “People don’t notice anything but my old beard.” She despises pity and avoids looking into the eyes of the people in her audiences; like most freaks, she has cultivated a blank, unseeing stare. When people look as if they feel sorry for her, especially women, it makes her want to throw something. She does not sell photographs of herself as many sideshow performers do and does not welcome questions from spectators. She will answer specific questions about her beard as graciously as possible, but when someone becomes inquisitive about her private life—“You ever been married?” is the most frequent query—she gives the questioner an icy look or says quietly, “None of your business.”

Barnell preferred the company of other freaks and lived with them whenever possible, either on the road or in special boardinghouses where they all congregated. She saw herself and was treated as one of the “aristocrats of the sideshow world,” because of her beard. As she explained to Mitchell, the economy of the sideshow was divided into three tiers. At the lowest level were novelty acts—reformed criminals, once-famous sports figures, war heroes, etc. Young Griffo, the boxer, became one late in life. These acts were only profitable for as long as the public remembered who they were. In the middle rung were “made freaks,” such as tattooed women, sword swallowers, or geeks who bit the heads off live animals. These performers had to have some level of skill or uniqueness, but they were still replaceable. The pinnacle of the sideshow were the “born freaks,” people whose unique bodies titillated audiences and could not be re-created: rubber boys, alligator girls, conjoined twins, bearded women, etc. Their acts were often exploitative, and some—such as Barnell herself—were forced into circus work, but within the sideshow, they were treated like the royalty they often claimed to be.

Barnell started her career as Princess Olga, a name that suggested both royal and foreign lineage. At various times, her barkers claimed that she was born in Budapest, Paris, Moscow, and Shanghai. This was an easy way to add mystique to a show, and many sideshow performers similarly embellished their biographies. Foreign parentage was a useful story because it not only made them more interesting, it also reassured good American audiences that they were biologically and culturally superior. When Coney Island sideshow impresario Samuel Gumpertz was asked why so many freaks came from outside the United States, he gave an explicitly eugenic answer: “The probable explanation is that the marriage laws are not as rigid as in the Western countries. There, very near relatives are frequently permitted to marry, and as a result deformities and shrunken bodies and freaks in human makeups occur.”30

In truth, most performers were American, and a good portion of those who were foreign-born were either survivors of human trafficking or were otherwise forced into performing. Around 1881, the performer Krao, for example, was taken from her home in Siam (now Laos) at the age of four by Guillermo Antonio Farini, who would adopt her and be her manager until the early 1900s. In different versions of the story, Farini kidnapped her, or rescued her from kidnappers, or was given her by the king of Siam. Regardless, it seems unlikely that her start on the stage was consensual. Krao spent decades being exhibited as (and eventually, exhibiting herself as) “the Missing Link.” Women of color with hypertrichosis (the technical term for “excess” hair) were never exhibited as bearded women. Instead, like Krao, they performed as missing links or animal girls. White women with beards could still qualify as women—especially if they talked about their marriages, dressed in a conventionally feminine way, and exhibited proper womanly decorum (at least onstage). But for women of color, who were already considered masculine, unattractive, and animalistic, having a beard pushed them outside the category of human entirely.

There is no evidence that Barnell saw herself as connected to any kind of larger community of people who transgressed gender, although her preference for living with sideshow performers probably stems from the same forces that drew other kinds of queer people together. But the public presence of bearded women, half-and-halfs, and other sideshow acts that played with gender contributed to a generally queer atmosphere at Coney Island. Like Ella Wesner and Florence Hines before her, Barnell’s stage presence constituted a public acknowledgment of queerness that was relatively nonthreatening to most Americans.

In 1926, James Monaco cowrote a song about such gender transgressors, possibly inspired by his time as a piano player on Coney Island. Called “Masculine Women! Feminine Men!,” the song’s gently ribbing tone suggested that playing with gender was strange, but also part of modern life. Its lyrics begin:

Hey hey women are going mad, today

Hey hey fellers are just as bad, I’ll say

Go anywhere, just stand and stare

You’ll say they’re bugs when you

look at the clothes they wear

Masculine Women Feminine Men

which is the rooster which is the hen

It’s hard to tell ’em apart today

The song goes on to catalog gender transgressions among family members, girlfriends, and even royalty, turning queerness from a scary part of modern life into a strange, funny, but ultimately relatable way of being—much as getting to know the freaks at Coney Island would surely have. Additionally, in the 1920s, an androgynous look for women was popularized by flappers, who bobbed their hair and cultivated “masculine” habits such as smoking and driving. With the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920—giving women the right to vote—many believed that the last vestiges of separation between the sexes would finally collapse entirely. No wonder “Masculine Women! Feminine Men!” would be a minor success in the latter part of the decade, getting recorded by multiple artists.

Feminine men—and gay men in general—already had a definite place at Coney Island. By at least 1910, female impersonators were the main attraction at some saloons at Coney, which we know because a young Jimmy Durante got his start in one called Diamond Tony’s. As Durante described it, “At our place and Jack’s [another Coney Island saloon], the entertainers were all boys who danced together and lisped. They called themselves Edna May and Leslie Carter and Big Tess and things like that.”31 However, Durante makes clear that while gay men were on the stage, they were not in the audience. Like many clubs that featured drag acts in the early part of the twentieth century, Diamond Tony’s was a straight bar. “Outside of the queer entertainers, our place was no different from most of the others,” Durante wrote. “The usual number of girls hung out there, and the customers were mostly on the level; that is to say, they were not interested in our entertainers any more than they would have been in the freaks that filled the Surf Avenue sidewalks.”

However, by the 1920s, at least one kind of establishment at Coney attracted large queer male crowds: the public bathhouses, which became increasingly popular once the subway reached the beach.

New York City’s oldest bathhouses date back to the 1850s. These grand institutions were privately run, located in Manhattan, mostly catered to the upper and middle classes, and functioned as social clubs as well as bathing pavilions. In the 1890s a push began to create city-run, municipal public baths that were free or low cost, to promote bathing in working-class districts, where private bathrooms were still rare. Reformers also worked to popularize the idea of bathing as essential to physical and moral health. By the early 1910s, Brooklyn had seven such bathhouses, mostly clustered around the working waterfront that bordered the East River.32

The bathhouses at Coney Island were something of a hybrid of these two kinds of institutions. They were privately run, but catered mostly to the working class. They served both social and hygienic roles. One of their primary functions was to rent bathing suits to city residents. Not only did few people own a bathing suit, but up until the late 1930s wearing bathing suits on city streets was prohibited, meaning you had to change somewhere at Coney. According to Michael Immerso’s Coney Island: The People’s Playground, by 1930,

there were more than thirty bathing establishments to select from. Large bathhouses such as Steeplechase Baths, Ward’s, and Washington Baths charged about fifty cents for a locker and provided amenities such as a pool, handball court, punching bags, and a sunbathing deck. Raven Hall, one of the oldest, had a picnic grove and dance pavilion. Silver’s Bath and Stauch’s were known for their steam baths, which were popular with Russian and Jewish patrons. Less prestigious establishments with fewer amenities charged as little as fifteen cents. Bathhouses were one more link to the city’s poorer neighborhoods, where public baths were familiar institutions. Community solidarity was transferred to many of Coney Island’s bathing establishments, which gained a loyal following among a particular neighborhood group.33

Like the rest of Coney, these bathhouses had their heyday in the 1920s. Although most served men, women, and families, a decidedly masculine culture grew up around some of these facilities. Certain bathhouses, such as Stauch’s and the Washington Baths, would become particularly popular with gay men.

The Washington Baths was one of the swankier places on the island, located on the beach at Twenty-first Street, on the western side of Coney. The giant two-story edifice was built around a central pool, like a hidden courtyard, accessed through a series of arches on the boardwalk. One block away, the baths had an annex with a saltwater pool, a bright pink stucco building with three-foot medallions featuring the head of King Neptune repeated along the walls. By at least 1929, the Washington Baths had a dedicated gay clientele, as the owners discovered to their chagrin on a balmy afternoon in the second week of August. As a publicity stunt, they had organized a male beauty contest, which was to be judged by singer Rudy Vallee, film star Carroll Nye, and Broadway actress Beryl Halley. Over twenty-five men competed, and a large crowd turned out to watch. Perhaps tipped off as to what was about to unfold, Vallee skipped the engagement at the last minute and sent his sister, Sobbie, to judge instead. Organizers realized the event was not going to be what they expected when the audience turned out to be mostly men. Soon, effeminate male contestants began “tripping across the front of the platform,” parading past the scandalized judges. The publicity manager for the event cautioned the judges not to vote for a contestant with “paint and powder on.” The manager had already instructed four contestants to take all their makeup off, but it was no use; almost all of the beauty kings were gay, and no amount of scrubbing their faces could hide it. Variety magazine reported that the most difficult part of the competition became “picking a male beaut who wasn’t a floozie.”34 The word “floozie” once again connected effeminate men to brassy, sexually forward women, much as they were in Jennie June’s day.

Interestingly enough, the women in the audience—described as “Coney Island dowagers”—seemed to have no problem with the gay male contestants, including the one who participated in full drag and the “pretty guy who pranced before the camera and threw kisses to the audience.” When Beryl Halley pointed out that these women had chosen “all the beauts with mascara on their eyelashes,” Sobbie yelled at them, “Ladies, don’t you know those boys are awful floozies?” The women persisted in their choices, even as Vallee’s sister explained plaintively that it was “a question of the sanctity of the home.” Nye finally instructed the women to choose only “a man who is tattooed or hairy,” assuming that they must be straight, but even that method seemed to fail. Finally, the judges discovered that a contestant was married to one of the “Coney Island dowagers” and awarded him first place. The other three prizes went to “brawny looking chaps who were not much to look at.” Their work done, “the fatigued judges fled before the disappointed beauts burst into tears.”

Although little other evidence points to the presence of gay men at Coney Island around this time, the size of the crowd, the number of contestants, their comfort at being campy in public, and the nonreaction of the Coney Island natives strongly suggests that this was not the first or only time gay men had gathered at the Washington Baths. Over the next few decades, that bathhouse would become a popular cruising spot for gay men, and we will return to it again in the 1940s and ’50s. Any institution that provided gender-segregated, semiclothed privacy (whether bathhouse, public bathroom, reformatory, jail, or boarding school) was likely to be a magnet for same-sex sexual activity—which New York City police and civilian crusaders began to understand in the 1920s.

During and immediately after World War I, the number of arrests for “degeneracy” (aka soliciting for sexual activity, or cruising) skyrocketed. According to the Committee of Fourteen, in both 1918 and 1919, degeneracy cases increased 50 percent over the year before. But even that was a low estimate because, as they noted in their bulletin, police “reports do not contain detailed figures of cases of degeneracy.”35 Men were still being arrested for the more general charge of disorderly conduct. In cases where convictions were made, these men were sent to be fingerprinted, and only then were they marked as degenerates. (The criminologist who invented fingerprinting, Henry P. DeForest, was also the doctor who first sent Loop-the-Loop to see R. W. Shufeldt. Criminology, like sexology, started from a belief that degeneracy could be read in the body, so it’s no surprise that the same scientists would practice both.) Starting in 1920, the Committee of Fourteen began writing proposed changes to the disorderly conduct law, breaking it into multiple subsections. By so doing, the committee hoped to track both degenerates and men who frequented female sex workers more closely.

In 1921, using the records of the Fingerprint Bureau, the committee released an internal report entitled “Sexual Perversion Cases in New York City Courts, 1916–1921.”36 At the start of that period, they found 92 cases of degeneracy. By 1920, that number had increased over 700 percent, to a whopping 756 cases. They also noted that 89 percent of all men arrested on degeneracy charges were eventually convicted—“a percentage much above the average of convictions for all offences.”

Not only were men who had sex with men more likely to be convicted than other offenders, men of color who had sex with other men were more likely to be convicted than white men. In their report, the committee broke convictions down into eight racial categories. Five of these categories were what we would today call white or Caucasian people: Anglo-Saxon (English), Latin (French, Spanish, Italian, and other Mediterranean-descended people), Teutonic (German and Northern European), Scandinavian (Swedish, Danish, etc.), and Slavs (Eastern European). The other three categories were Near East (Middle Eastern), Orients (Asian), and Negroes (black). White people accounted for 89 percent of degeneracy arrests, Middle Eastern people 4 percent, black people 6 percent, and people of Asian descent just 1 percent. At the time, New York City’s population was around 97 percent white. The Committee of Fourteen documented their own lack of informants of color, and the unwillingness of the police to pursue vice cases in primarily black neighborhoods, yet despite both these limiting factors, men of color were still being arrested in higher-than-expected numbers. Whiteness was not yet the consolidated identity we know it as today, but it still offered some protection from police abuse.

Regardless of the race of the men involved, the committee believed that two factors contributed to this rise in degeneracy cases. When considered together, their two arguments highlight the changing understanding of sexuality. The first cause they pointed to was their own success. By driving heterosexual prostitution further underground, they believed they had opened the door for degeneracy to take its place. This belief was in line with older ways of thinking, such as that of the judge who sentenced Young Griffo, which saw same-sex sexual contact as a substitute for heterosexual sex under certain conditions. Homosexuality wasn’t a permanent and fixed identity defined by the gender of your partner; instead it was an action that almost any man might undertake if the circumstances were right.

This probably had some influence, the Committee of Fourteen conceded, but not as much as World War I. During the war, “American boys undoubtedly became familiar with perverse practices while in France or while at sea and to some extent while in the large cities of their own country,” they wrote. The idea that homosexuality was something that you learned or were inducted into was the committee’s great fear. “The pervert, not deeming his acts unnatural, is constantly seeking converts to his practices,” they wrote. “Figures indicate that their efforts are successful. This makes the situation a serious one requiring consideration and special action” (emphasis in the original). The idea of the predatory homosexual, out to recruit innocent “American boys” into his way of life, was taking hold. Sex acts between men were no longer discrete disgusting activities, they were the gateway to becoming a specific type of person—the homosexual. An invert was obvious from his or her contrary gender presentation, but anyone could be a homosexual, including war heroes. Now that the idea of sexual orientation was spreading, same-sex sexual contact between gender-normative men had higher stakes and needed to be policed more heavily. The committee quickly took up that work.

However, they noted problems with their World War I theory. In particular, 63 percent of the arrests they studied were of men over the age of thirty, making it unlikely that they were “boys” who had been corrupted by immoral foreigners, desperate sailors, or wicked urbanites. Many of them were probably too old to have served in World War I. The war still contributed to the rising tally of degeneracy arrests by bringing large numbers of men together in urban centers, but it is unlikely that these men learned to be gay while serving as young soldiers. Yet while they noted this contradiction, the committee made no efforts to account for it or adjust their theories.

In the pages of the committee’s report were two pieces of information that might have helped them to understand the rise in degeneracy cases. First, they noted that certain policemen were responsible for most of the convictions. These officers worked in a small number of locations, mostly near Herald Square, Times Square, Union Square, Madison Square Park, and Columbus Circle. What did all of these places have in common? They were transportation hubs that were frequented by men of all kinds, making them easy places to cruise without drawing attention. Neither laborer nor businessman, sailor nor painter, would stick out if he was seen lingering in these places. The second, and arguably more important piece of information, was where in those areas the arrests were taking place: “chiefly motion picture theaters and subway toilets.” Both were recent additions to the city’s landscape. The pattern of these arrests suggested that rather than learning a new vice from somewhere far away, or using homosexuality to compensate for a lack of access to heterosexual sex, men were suddenly finding that spaces to solicit for homosexual sex were widely available—another way in which the queer world was expanding with the urbanization of New York.

And find sex they did. Although the exact numbers fluctuate, over the next twenty-five years, degeneracy arrests steadily increased throughout New York City. By the end of the 1920s, over one thousand men would be arrested annually—most while soliciting (or having) sex in a subway bathroom. The number of arrests in Brooklyn was generally low (a few dozen per year at most), but men from all five boroughs were regularly arrested in Manhattan. In 1945, the arrest count hit two thousand for the first time. In 1947, when over thirty-one hundred men were arrested for degeneracy, the Magistrate’s Report would note that “the basis of the charge in all cases is overt homosexual activity in a public place, usually a subway or theater, toilet or park.”37 The subway provided easy connection between nascent “gayborhoods” such as Harlem, Greenwich Village, Coney Island, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, while simultaneously creating hundreds of small, private, male-only spaces where men disrobed together. The city probably couldn’t have designed a better way to promote gay sex if it had tried.

We know all of this because in 1923 the Committee of Fourteen successfully fought for the passage of the Schackno Bill, which divided disorderly conduct into ten subsections. Subsection DC-8 made it a misdemeanor for any man to “frequent or loiter about any public place soliciting men for the purpose of committing a crime against nature or other lewdness.”38 For the first time in New York City history, the law specifically criminalized consensual same-sex activity. More dangerously, it criminalized any man that the police decided was looking for same-sex activity. The law was so broad that homosexual men (or any man who seemed homosexual) could now be arrested simply for being in public. Much like the prostitute, the homosexual was now a moral danger regardless of whether he was actually committing a sexual act. No longer would the police need to falsify evidence or entrap men into soliciting sex (though both practices would continue).

Curiously, however, while this was the Committee of Fourteen’s explicit goal in changing the disorderly conduct law, it seems the police and the courts had different ideas about the Schackno Bill. In describing the changes to the law in its annual report for 1923, the Magistrate’s Court barely mentioned the prosecution of sexual activity. Instead, its focus was on the way in which the bill provided for increased oversight and prosecution of pickpockets. While this might seem laughable today, at the time eugenicists viewed being a pickpocket as a biological, inheritable, and permanent condition—nearly identically to the way they viewed homosexuality. In the court’s 1923 annual report, Chief City Magistrate William McAdoo wrote:

As a biological proposition, I believe with eminent psychologists that this species of rascals are emotionally deficient, ill balanced in physical brain and incurable thieves who ought to be in continuous custodial care and not running in and out of jails and penitentiary, but in establishments where they could lead useful and improving lives.39

As draconian as it might sound today, the chief magistrate of the City of New York wanted to institutionalize pickpockets for life. In subsequent annual reports, only two types of disorderly conduct arrests were tracked specifically: pickpockets (or “jostlers”) and degenerates (aka homosexuals). The other eight subsections of the law were tracked together as disorderly conduct cases. At every step of the judicial process, men arrested for degeneracy received harsher treatment than other cases. They were less likely to be discharged and more likely to be convicted, and when they were convicted, they received larger fines and longer sentences at the workhouse. Even “incurable thieves” such as pickpockets received better treatment (although only marginally).

By providing the city with explicit yearly data on the (increasing) numbers of men soliciting for sex, the Schackno Bill set the stage for all future crackdowns on homosexuality. Before you can effectively regulate a behavior, you have to be able to define, locate, and track it. In the coming decades, in an effort to regulate gay male sex, New York City would try everything from mass arrests to a first-of-its-kind program that sent men convicted of degeneracy to therapists instead of jails—none of which would have been possible without the Schackno Bill.

We know little about most of the men who were arrested as degenerates in the 1920s. While the law established a way to track arrests, it didn’t define what should happen to these men after arrest, or how/if records of their arrests should be kept in perpetuity. Since disorderly conduct was a misdemeanor, these arrests almost never led to trials or stories in the press. However, the exploits of one of Brooklyn’s most famous early twentieth-century residents can give us some insight into the world of subway cruising (and waterfront cruising. And bathhouse cruising. And speakeasy cruising. And … you get the picture).

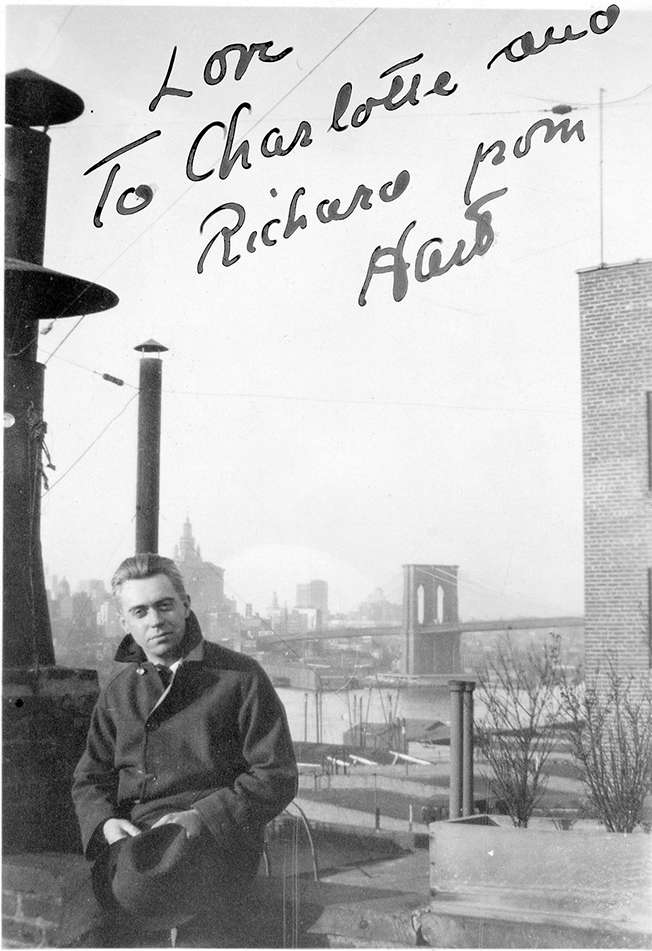

Photo of poet Hart Crane (c. 1920). (Photo courtesy of the Richard W. Rychtarik/Hart Crane Papers; MSS 103; box 1; folder 3; Fales Library and Special Collections.)

The poet Hart Crane was born just a few months shy of the start of the century, on July 21, 1899, in Garrettsville, Ohio. He was seventeen when he first landed in New York City, in the middle of World War I. A high school dropout from a wealthy and tempestuous family, he didn’t stay long. Within a few months, Crane moved to Cleveland, where he worked a variety of jobs, some for the war effort, some as an “adman” and copywriter, and some for his father, a self-made millionaire who built a large candy company (in part by licensing a new ring-shaped candy known as Life Savers). In 1923, the year the Schackno Bill was passed, Crane returned to New York City, now a poet of some growing renown, ready to shed his Midwestern roots and roar his way into the 1920s. During this period he would produce his most renowned work, The Bridge, an epic six-part poem whose central image was the Brooklyn Bridge, a structure he revered. In many ways, Crane—with his love of jazz and gin, his outsize personality, his sui generis genius, his ever increasingly frantic life, and his early death—exemplifies the rise and tragic fall of the entire decade.

Even as a young man, Crane’s eyes seemed always hooded, with tired circles beneath. His thick dark hair leaped away from his temples in a great upright shock, though he would go gray (the exact color of a seagull, according to friends) while still in his twenties. His personality was boisterous, oversize, and equal parts entertaining and irritating. Crane made friends nearly as easily as he lost them, and at one point or another he counted among his admirers many of the leading men of American arts and letters, including Eugene O’Neill, Malcolm Cowley, Waldo Frank, Charlie Chaplin, Walker Evans, E. E. Cummings, John Dos Passos, William Carlos Williams, and Alfred Stieglitz. His relationships with female artists were more fraught; although he counted some (such as Caroline Gordon) as friends, in his letters he routinely dismissed and diminished female poets such as Marianne Moore, Harriet Monroe, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Although he left behind just two slim volumes of poetry when he died at the age of thirty-two, his extensive correspondence gives us insight into his life. Crane’s letters show how having queer peers can crucially change the way in which a historical figure is remembered. In his introduction to Crane’s collected correspondence, Langdon Hammer wrote, “There are obvious differences between his letters to straight and gay friends, manifest in idiom and tone as much as in what is said.”40 Crane’s letters to his gay peers contain more camp, more frank sexual discussion, and more honest pathos. As is true for Mabel Hampton, part of the reason we know so much about Crane is because of these other queer people who preserved his legacy in letters.

From childhood on, Crane was resolute about two things: his homosexuality and his poetry. At the age of six he declared that he would be a poet. Upon first arriving in New York at seventeen, he wrote to his father, “I have powers, which, if correctly balanced, will enable me to mount to extraordinary latitudes.”41 Although he was right about his literary abilities, Crane never achieved balance of any kind. His poetry seemed to thrive on a hectic, herky-jerky life full of tremendous highs and suicidal lows. He wrote best (or at least most often) when drunk. He had a habit of sneaking away from parties to write in a side room, the Victrola blaring as he did. His poetry was dense and imagistic, but also highly rhythmic; he often said he was looking for a way to translate jazz into words.

Crane had sexual experiences with men dating back to his midadolescence. Like Walt Whitman before him, Crane had a fondness for sailors, laborers, and other working-class men. This fascination rested on many pillars: the frisson of excitement that came with class-jumping or slumming, the unlikeliness of running into anyone he knew in the saloons where these men gathered, his own sense of shame around not living up to a certain standard of masculinity, and the greater degree of acceptance of male-male sexual activity that prevailed in some working-class neighborhoods. At the age of nineteen, he came out to his friend and fellow literary young Turk Gorham Munson in a letter, writing, “This ‘affair’ that I have been having, has been the most intense and satisfactory one of my whole life, and I am all broken up at the thought of leaving him. Yes, the last word will jolt you.”42

While Crane was open about his desires with most of the people in his life, he rightly feared how he would be perceived because of it. As part of the first generation to grow up with the concept of homosexuality, Crane worked hard to present himself as a straight-seeming, gender-conforming man. As his friend the poet Samuel Loveman recalled:

He confided to me … that he had so practiced the art of camouflaging and hiding anything that might possibly be construed as feminine in his makeup—[hence] the long and somewhat ponderous, swaggering stride, his inveterate cigar-smoking, the Whitmanesque habit of wearing expensive but extremely comfortable and easy “crash” clothes—what had once been assumed actually became a part of him.43

Some of his contemporaries were put off by Crane’s queerness, such as poet William Carlos Williams, who admitted that while he admired Crane’s writing, he avoided him because he was a “crude homo” and “cock sucker.”44 Others, such as the author Yvor Winters, liked Crane personally but believed that his sexuality precluded him from writing poetry that could speak to most people—or as Winters put it in a damning review that ended their friendship, Crane was “temperamentally unable to understand a very wide range of experience”45 and was thus limited in what he could produce upon the page.

By the age of twenty-three, when Crane was preparing for his return to New York, he realized that being out put him in a precarious economic position. “I discover I have been all-too easy all along in letting out announcements of my sexual predilections,” he wrote to his friend Munson on March 2, 1923. “When you’re dead it doesn’t matter, and this statement proves my immunity from any ‘shame’ about it. But I find the ordinary business of ‘earning a living’ entirely too stringent to want to add any prejudices against me of that nature in the minds of any publicans and sinners.”46 He urged Munson to be discreet on Crane’s behalf, but discretion was never among Crane’s strengths himself.

Crane had already begun to conceptualize his masterwork, The Bridge, before he returned to the city. In another letter to Munson, he described the poem as “a mystical synthesis of ‘America,’” and the idea of the bridge metaphor itself as a “symbol of our constructive future, our unique identity.”47 Crane explicitly saw himself carrying on the legacy of Walt Whitman and wanted The Bridge to combine the hopeful, epic lyricism of Leaves of Grass with the ultramodern poetics of T. S. Eliot (whom Crane found depressing and nihilistic, though prodigiously talented). The Bridge was conceived at a moment when Crane’s America was full of hope: the war was over, the economy was booming, the twenties were roaring, and gay life was beginning to find public expression. Crane’s poem would contain all of that, by telling the history of the continent, from the birth of Pocahontas to the construction of the subway. The anchoring metaphor would be the Brooklyn Bridge, that towering symbol of New York City (the beloved center of the modernist movement in art and literature), which was built during the last flowering of Victorian Romanticism. It “bridged” both worlds—and both boroughs—as Crane hoped his writing would. Similarly, he hoped his writing would also bridge the queer and straight worlds, offering queer love—only slightly disguised—as an experience with which any reader might identify.

As he worked on the poem, Crane wrote, “I begin to feel myself directly connected to Whitman.”48 Part of this connection rested on his desire for the same kind of “adhesive brotherhood” that Whitman had tried to chaunt and yawp into existence some seventy years prior. Sections of The Bridge are love poems, and Crane was determined (in part) to show that there was space for queer love in the American mythos, and that queer love could create a universal metaphor with which all people could identify. In the fourth section of The Bridge, “Cape Hatteras,” Crane invoked Whitman by name, writing:

O Walt!—Ascensions of thee hover in me now

As thou at junctions elegiac, there, of speed

With vast eternity, dost wield the rebound seed!

.….….….……

… O, upward from the dead

Thou bringest tally, and a pact, new bound

Of living brotherhood!

.….…..

… thy wand

Has beat a song, O Walt,—there and beyond!

And this, thine other hand, upon my heart

As the last verse makes clear, Crane’s connection to this living brotherhood, and to Whitman, is sexual. Whitman’s one hand might be on his heart, but the other is firmly on his wand. As they would be for many, queer love, Walt Whitman, and Brooklyn were intimately connected in Crane’s cosmology.

It was queer love that brought Crane to Brooklyn, early in 1924. Emil Opffer was a Danish sailor and journalist, with blond hair, blue eyes, and a “generous and gregarious disposition.”49 He volunteered occasionally at the storied Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village (where Eugene O’Neill’s plays were first staged), which is probably how he entered Crane’s social circle. He was a few years older than Crane, and he was calm where Crane was tempestuous, quiet where Crane was loud, and easy where Crane was difficult. Opffer worked on commercial ships that traveled from Brooklyn down to South America, and sometimes to California. His father had been a journalist of some renown in Norway, but now lived in Brooklyn Heights, where he was the editor of Nordlyset, a paper that served the two-hundred-thousand-strong Danish community in the city.

Opffer was, without a doubt, the love of Crane’s life and the muse that inspired some of his most beautiful poetry. Soon after they met, Crane wrote a rapturous letter to a friend about being with Opffer, describing “the ecstasy of walking hand in hand across the most beautiful bridge of the world, the cables enclosing us and pulling us upward in such a dance as I have never walked and never can walk with another.”50 In Opffer, Crane found that sexual brotherhood he longed for, and he immortalized their relationship in the poetic sequence he called “Voyages.” The name references Opffer’s travels, but these journeys were also sexual ones, as part 3 of “Voyages” makes clear:

Past whirling pillars and lithe pediments,

Light wrestling there incessantly with light,

Star kissing star through wave on wave unto

Your body rocking!

And where death, if shed,

Presumes no carnage, but this single change,—

Upon the steep floor flung from dawn to dawn

The silken skilled transmemberment of song;

Permit me voyage, love, into your hands …

The first four lines describe an intense sexual encounter (“body rocking”) between two men (the “whirling pillars” and “lithe pediments”). “Death” here refers to la petite mort—literally, “a little death,” but also French slang for orgasm—after which the lovers’ clothes are found flung to the floor. Then, after a short break, the lovers begin their sexual voyage again. Although Crane was often criticized (rightfully) for his oblique and incomprehensible poetry, Opffer inspired some of his most eloquent and readable lines.

When the two were first introduced, Opffer was living with his mother and stepfather in Manhattan (when not out at sea); however, Crane’s tendency to show up at his door at three in the morning soon led to a rift with his family. “I have to lead my life as best I can,” Opffer told his stepfather. “I don’t want to give up Hart’s friendship. After my dreary life at sea, I need some fun.”51

Crane was bouncing around apartments in Greenwich Village, spending money he didn’t have and wearing thin the hospitality of friends. He needed somewhere from which to write The Bridge. Opffer proposed a solution that would help them both: they would move into the building where Opffer’s father lived, in Brooklyn Heights. Opffer’s father (also named Emil) lived in a kind of commune founded by artist and patron Hamilton Easter Field and his adopted son, sculptor Robert Laurent (who was rumored to have also been Field’s lover).

Field came from Brooklyn royalty. According to his peers, he was “tall and dark-haired, Byronic in appearance, bohemian by temperament, and said to be homosexual.”52 In 1845, his grandfather built the family home, called the Field Mansion, at 106 Columbia Heights, as well a number of other buildings on the block, which were collectively referred to as Quaker Row. Field was born there in 1873 and spent most of his young life in Brooklyn, except for a semester at Harvard and a few years studying art in Europe. By 1905, he had returned home and become a painter of small renown. When he had his first exhibition in Manhattan’s Clausen Gallery in March of that year, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called him “the Height’s first artist who promises to make an important name for himself.”53 Over the next seventeen years, he would turn his corner of Brooklyn into a celebrated destination for artists and art enthusiasts. Beginning in 1912, he hosted numerous exhibitions in his home, which he dubbed the Ardsley Studio. In 1916, he bought two other buildings on Quaker Row, including 110 Columbia Heights—the building where Washington Roebling had lived while completing the Brooklyn Bridge. Field turned all three buildings into an art school and commune, which he called the Ardsley School. There, he showed a stunning variety of work, from historic Japanese prints to cutting-edge cubist paintings and sculptures.

Photo of Columbia Heights (c. 1920), facing North toward the Brooklyn Bridge. Hart Crane, Emil Opffer, and Hamilton Easter Field all lived at 110 Columbia Heights. (Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Eagle Photographs—Brooklyn Public Library—Brooklyn Collection.)

The three houses of the Ardsley School were “connected on the basement and parlour floors, with an art school situated in the basement; the upper stories were residential.”54 Field had previously established an art school in Ogunquit, Maine, which played host to famous queer artists such as Marsden Hartley, but Field decamped to Brooklyn in part because the Maine locals found him so strange. In an interview given many decades later, Field’s close friend Lloyd Goodrich attributed part of this less than warm reception to Field’s being “fundamentally … a homosexual.”55 Field continued to run an art school in Ogunquit during the summers, but throughout the 1910s and into the 1920s he primarily lived in Brooklyn, where he found a welcoming home. His presence there would entice a wide variety of admirers to cross the East River. William Henry Fox, the director of the Brooklyn Museum, described Field as playing constant host to “distinguished strangers from overseas, ‘Society folks,’ artists, musicians, writers … and on one occasion I saw in his parlors an East Indian princess.”56

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle considered Field the epitome of a local boy done good; when he died, the paper wrote, “Among the men who have identified Brooklyn with the higher spirit of art in America and in the world, not one had a keener art sense, or so much of capacity for intelligent and sympathetic criticism, as Hamilton Easter Field.” In fact, he would review art exhibitions for The Eagle for a number of years before he founded his own influential journal, The Arts, in 1919, which The Eagle called “perhaps the most progressive, certainly the most authoritative, [journal] in the country.”57 He took seriously his role as a booster of Brooklyn and its artists; not only was Field the founder of the organization the Salons of America, he was also the president of the Brooklyn Society of Artists, the director of the Independent Society of Artists, a member of the executive committee for Modern Artists of America, and a member in good standing of the Brooklyn Water Color Society. Although many critics lamented that he never lived up to his natural talent as a painter, Field was unsurpassed as a patron.

Sculptor Robert Laurent was one of many talented artists that Field found in his frequent trips around the world. Laurent was twelve when Field discovered him in France and became his patron. Although he was frequently described as Field’s adopted son, there seems to have been no formal adoption arrangement between them. The two were virtually inseparable (even after Laurent married sometime around 1918). When Field died of pneumonia in 1922, he left everything to Laurent, “a life long friend, with whom he lived,” as one obituary put it.58

Laurent continued the tradition of renting out inexpensive rooms to artists and writers, although the Ardsley School seems to have died with Field. It’s unclear how well Hart Crane knew Laurent, or if he ever met Field, since Crane moved to Columbia Heights two years after Field died. However, many other art luminaries passed through the buildings in those years. The author John Dos Passos lived there while Crane and Opffer were in residence, and it’s possible that this influenced the sympathetic gay character he included in his novel Manhattan Transfer. Other famous residents included visual artists Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Adelaide Lawson, Katherine Schmidt, and Stefan Hirsch (who would quite coincidentally be one of the last people to see Crane alive).

For Crane, the move to Columbia Heights had the mark of providence. Not only would he be living in the same building as Opffer, whom he nicknamed Goldilocks and Phoebus Apollo, but he would literally be in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, in a building directly connected to its history. Emil Opffer Sr. actually lived in Washington Roebling’s old room. “That window is where I would be most remembered of all,” Crane wrote rapturously to his friend Waldo Frank.59 When Opffer Sr. died during minor surgery a few months after the pair moved in, Crane took over his room and described the view to his mother: