17

Miscellaneous remarks on the country. On its vegetable productions. On its climate. On its animal productions. On its natives, etc.

THE journals contained in the body of this publication, illustrated by the map which accompanies it, are, I conceive, so descriptive of every part of the country known to us that little remains to be added beyond a few general observations.

The first impression made on a stranger is certainly favourable. He sees gently swelling hills connected by vales which possess every beauty that verdure of trees, and form, simply considered in itself, can produce; but he looks in vain for those murmuring rills and refreshing springs which fructify and embellish more happy lands. Nothing like those tributary streams which feed rivers in other countries are here seen; for when I speak of the stream at Sydney, I mean only the drain of a morass; and the river at Rose Hill is a creek of the harbour, which above high water mark would not in England be called even a brook. Whence the Hawkesbury, the only freshwater river known to exist in the country, derives its supplies, would puzzle a transient observer. He sees nothing but torpid unmeaning ponds (often stagnant and always still, unless agitated by heavy rains) which communicate with it. Doubtless the springs which arise in Caermarthen mountains† may be said to constitute its source. To cultivate its banks within many miles of the bed of the stream (except on some elevated detached spots) will be found impracticable, unless some method be devised of erecting a mound, sufficient to repel the encroachments of a torrent which sometimes rises fifty feet above its ordinary level, inundating the surrounding country in every direction.

The country between the Hawkesbury and Rose Hill is that which I have hitherto spoken of. When the river is crossed, this prospect soon gives place to a very different one. The green vales and moderate hills disappear at the distance of about three miles from the river side, and from Knight Hill†2, and Mount Twiss,* the limits which terminate our researches, nothing but precipices, wilds and deserts are to be seen. Even these steeps fail to produce streams. The difficulty of penetrating this country, joined to the dread of a sudden rise of the Hawkesbury, forbidding all return, has hitherto prevented our reaching Caermarthen mountains.

Let the reader now cast his eye on the relative situation of Port Jackson. He will see it cut off from communication with the northward by Broken Bay, and with the southward by Botany Bay; and what is worse, the whole space of intervening country yet explored (except a narrow strip called the Kangaroo Ground) in both directions, is so bad as to preclude cultivation.

The course of the Hawkesbury will next attract his attention. To the southward of every part of Botany Bay we have traced this river; but how much farther in that line it extends we know not. Hence its channel takes a northerly direction and finishes its course in Broken Bay, running at the back of Port Jackson in such a manner as to form the latter into a peninsula.

The principal question then remaining is, what is the distance between the head of Botany Bay and the part of the Hawkesbury nearest to it? And is the intermediate country a good one, or does it lead to one which appearances indicate to be good? To future adventurers who shall meet with more encouragement to persevere and discover than I and my fellow wanderer[s] did, I resign the answer. In the meantime the reader is desired to look at the remarks on the map, which were made in the beginning of August 1790, from Pyramid Hill, which bounded our progress on the southern expedition; when, and when only, this part of the country has been seen.

It then follows that from Rose Hill to within such a distance of the Hawkesbury as is protected from its inundations, is the only tract of land we yet know of in which cultivation can be carried on for many years to come. To aim at forming a computation of the distance of time, of the labour and of the expense, which would attend forming distinct convict settlements, beyond the bounds I have delineated; or of the difficulty which would attend a system of communication between such establishments and Port Jackson, is not intended here.

Until that period shall arrive, the progress of cultivation, when it shall have once passed Prospect Hill, will probably steal along to the southward, in preference to the northward, from the superior nature of the country in that direction, as the remarks inserted in the map will testify.†3

Such is my statement of a plan which I deem inevitably entailed on the settlement at Port Jackson. In sketching this outline of it let it not be objected that I suppose the reader as well acquainted with the respective names and boundaries of the country as long residence and unwearying journeying among them have made the author. To have subjoined perpetual explanations would have been tedious and disgusting. Familiarity with the relative positions of a country can neither be imparted, or acquired, but by constant recurrence to geographic delineations.

On the policy of settling, with convicts only, a country at once so remote and extensive, I shall offer no remarks. Whenever I have heard this question agitated since my return to England, the cry of, ‘What can we do with them! Where else can they be sent!’ has always silenced me.

Of the soil, opinions have not differed widely. A spot eminently fruitful has never been discovered. That there are many spots cursed with everlasting and unconquerable sterility, no one who has seen the country will deny. At the same time I am decidedly of opinion that many large tracts of land between Rose Hill and the Hawkesbury, even now, are of a nature sufficiently favourable to produce moderate crops of whatever may be sown in them. And provided a sufficient number of cattle*2 be imported to afford manure for dressing the ground, no doubt can exist that subsistence for a limited number of inhabitants may be drawn from it. To imperfect husbandry, and dry seasons, must indubitably be attributed part of the deficiency of former years. Hitherto all our endeavours to derive advantage from mixing the different soils have proved fruitless, though possibly only from want of skill on our side.

The spontaneous productions of the soil will be soon recounted. Every part of the country is a forest: of the quality of the wood take the following instance. The Supply wanted wood for a mast, and more than forty of the choicest young trees were cut down before as much wood as would make it could be procured, the trees being either rotten at the heart or riven by the gum which abounds in them. This gum runs not always in a longitudinal direction in the body of the tree, but is found in it in circles, like a scroll. There is however, a species of light wood which is found excellent for boat building, but it is scarce and hardly ever found of large size.

To find limestone many of our researches were directed. But after repeated assays with fire and chemical preparations on all the different sorts of stone to be picked up, it is still a desideratum. Nor did my experiments with a magnet induce me to think that any of the stones I tried contained iron. I have, however, heard other people report very differently on this head.

The list of esculent vegetables and wild fruits is too contemptible to deserve notice, if the sweet tea†4 whose virtues have been already recorded, and the common orchis root be excepted. That species of palm tree which produces the mountain cabbage is also found in most of the freshwater swamps, within six or seven miles of the coast.†5 But it is rarely seen farther inland. Even the banks of the Hawkesbury are unprovided with it. The inner part of the trunk of this tree was greedily eaten by our hogs, and formed their principal support. The grass, as has been remarked in former publications, does not overspread the land in a continued sward, but arises in small detached tufts, growing every way about three inches apart, the intermediate space being bare; though the heads of the grass are often so luxuriant as to hide all deficiency on the surface. The rare and beautiful flowering shrubs, which abound in every part, deserve the highest admiration and panegyric.†6

Of the vegetable productions transplanted from other climes, maize flourishes beyond any other grain. And as it affords a strong and nutritive article of food, its propagation will, I think, altogether supersede that of wheat and barley.

Horticulture has been attended in some places with tolerable success. At Rose Hill I have seen gardens which, without the assistance of manure, have continued for a short time to produce well grown vegetables. But at Sydney, without constantly dressing the ground, it was in vain to expect them; and with it a supply of common vegetables might be procured by diligence in all seasons. Vines of every sort seem to flourish. Melons, cucumbers and pumpkins run with unbounded luxuriancy, and I am convinced that the grapes of New South Wales will, in a few years, equal those of any other country. ‘That their juice will probably hereafter furnish an indispensable article of luxury at European tables’, has already been predicted in the vehemence of speculation. Other fruits are yet in their infancy; but oranges, lemons and figs (of which last indeed I have eaten very good ones) will, I dare believe, in a few years become plentiful. Apples and the fruits of colder climes also promise to gratify expectation. The banana-tree has been introduced from Norfolk Island, where it grows spontaneously.

Nor will this surprise, if the genial influence of the climate be considered. Placed in a latitude where the beams of the sun in the dreariest season are sufficiently powerful for many hours of the day to dispense warmth and nutrition, the progress of vegetation never is at a stand. The different temperatures of Rose Hill and Sydney, in winter, though only twelve miles apart, afford, however, curious matter of speculation. Of a well attested instance of ice being seen at the latter place, I never heard. At the former place its production is common, and once a few flakes of snow fell. The difference can be accounted for only by supposing that the woods stop the warm vapours of the sea from reaching Rose Hill, which is at the distance of sixteen miles inland; whereas Sydney is but four.*3 Again, the heats of summer are more violent at the former place than at the latter, and the variations incomparably quicker. The thermometer has been known to alter at Rose Hill, in the course of nine hours, more than 50°; standing a little before sunrise at 50°, and between one and two at more than 100°. To convey an idea of the climate in summer, I shall transcribe from my meteorological journal, accounts of two particular days which were the hottest we ever suffered under at Sydney.

December 27th 1790. Wind NNW; it felt like the blast of a heated oven, and in proportion as it increased the heat was found to be more intense, the sky hazy, the sun gleaming through at intervals.

My observations on this extreme heat, succeeded by so rapid a change, were that of all animals, man seemed to bear it best. Our dogs, pigs and fowls lay panting in the shade, or were rushing into the water. I remarked that a hen belonging to me, which had sat for a fortnight, frequently quitted her eggs and showed great uneasiness, but never remained from them many minutes at one absence; taught by instinct that the wonderful power in the animal body of generating cold in air heated beyond a certain degree, was best calculated for the production of her young. The gardens suffered considerably. All the plants which had not taken deep root were withered by the power of the sun. No lasting ill effects, however, arose to the human constitution. A temporary sickness at the stomach, accompanied with lassitude and headache, attacked many, but they were removed generally in twenty-four hours by an emetic, followed by an anodyne. During the time it lasted, we invariably found that the house was cooler than the open air, and that in proportion as the wind was excluded, was comfort augmented.

But even this heat was judged to be far exceeded in the latter end of the following February, when the north-west wind again set in, and blew with great violence for three days. At Sydney, it fell short by one degree of what I have just recorded: but at Rose Hill, it was allowed, by every person, to surpass all that they had before felt, either there or in any other part of the world. Unluckily they had no thermometer to ascertain its precise height. It must, however, have been intense, from the effects it produced. An immense flight of bats driven before the wind, covered all the trees around the settlement, whence they every moment dropped dead or in a dying state, unable longer to endure the burning state of the atmosphere.†7 Nor did the perroquettes, though tropical birds, bear it better.†8 The ground was strewed with them in the same condition as the bats.

Were I asked the cause of this intolerable heat, I should not hesitate to pronounce that it was occasioned by the wind blowing over immense deserts, which, I doubt not, exist in a north-west direction from Port Jackson, and not from fires kindled by the natives. This remark I feel necessary, as there were methods used by some persons in the colony, both for estimating the degree of heat and for ascertaining the cause of its production, which I deem equally unfair and unphilosophical. The thermometer, whence my observations were constantly made, was hung in the open air, in a southern aspect, never reached by the rays of the sun, at the distance of several feet above the ground.

My other remarks on the climate will be short. It is changeable beyond any other I ever heard of; but no phenomena sufficiently accurate to reckon upon, are found to indicate the approach of alteration. Indeed, for the first eighteen months that we lived in the country, changes were supposed to take place more commonly at the quartering of the moon than at other times. But lunar empire afterwards lost its credit. For the last two years and a half of our residing at Port Jackson, its influence was unperceived. Three days together seldom passed without a necessity occurring for lighting a fire in an evening. A habit d’ete, or a habit de demi sáison,†9 would be in the highest degree absurd. Clouds, storms and sunshine pass in rapid succession. Of rain, we found in general not a sufficiency, but torrents of water sometimes fall. Thunderstorms, in summer, are common and very tremendous, but they have ceased to alarm, from rarely causing mischief. Sometimes they happen in winter. I have often seen large hailstones fall. Frequent strong breezes from the westward purge the air. These are almost invariably attended with a hard clear sky. The easterly winds, by setting in from the sea, bring thick weather and rain, except in summer, when they become regular sea-breezes. The aurora australis is sometimes seen, but is not distinguished by superior brilliancy.

To sum up: notwithstanding the inconveniences which I have enumerated, I will venture to assert in few words that no climate hitherto known is more generally salubrious,*4 or affords more days on which those pleasures which depend on the state of the atmosphere can be enjoyed, than that of New South Wales. The winter season is particularly delightful.

The leading animal production is well known to be the kangaroo. The natural history of this animal will, probably, be written from observations made upon it in England, as several living ones of both sexes have been brought home. Until such an account shall appear, probably the following desultory observation may prove acceptable.

The genus in which the kangaroo is to be classed I leave to better naturalists than myself to determine. How it copulates, those who pretend to have seen disagree in their accounts: nor do we know how long the period of gestation lasts. Prolific it cannot be termed, bringing forth only one at a birth, which the dam carries in her pouch wherever she goes until the young one be enabled to provide for itself; and even then, in the moment of alarm, she will stop to receive and protect it. We have killed she-kangaroos whose pouches contained young ones completely covered with fur and of more than fifteen pounds weight, which had ceased to suck and afterwards were reared by us. In what space of time it reaches such a growth as to be abandoned entirely by the mother, we are ignorant. It is born blind, totally bald, the orifice of the ear closed and only just the centre of the mouth open, but a black score, denoting what is hereafter to form the dimension of the mouth, is marked very distinctly on each side of the opening. At its birth, the kangaroo (notwithstanding it weighs when full grown 200 pounds) is not so large as a half-grown mouse. I brought some with me to England even less, which I took from the pouches of the old ones. This phenomenon is so striking and so contrary to the general laws of nature, that an opinion has been started that the animal is brought forth not by the pudenda, but descends from the belly into the pouch by one of the teats which are there deposited. On this difficulty, as I can no throw no light, I shall hazard no conjecture. It may, however, be necessary to observe that the teats are several inches long and capable of great dilatation. And here I beg leave to correct an error which crept into my former publication wherein I asserted that, ‘the teats of the kangaroo never exceed two in number.’ They sometimes, though rarely, amount to four. There is great reason to believe that they are slow of growth and live many years. This animal has a clavicle, or collarbone, similar to that of the human body. The general colour of the kangaroo is very like that of the ass, but varieties exist. Its shape and figure are well known by the plates which have been given of it. The elegance of the ear is particularly deserving of admiration. This far exceeds the ear of the hare in quickness of sense and is so flexible as to admit of being turned by the animal nearly quite round the head, doubtless for the purpose of informing the creature of the approach of its enemies, as it is of a timid nature and poorly furnished with means of defence; though when compelled to resist, it tears furiously with its forepaws, and strikes forward very hard with its hind legs. Notwithstanding its unfavourable conformation for such a purpose, it swims strongly; but never takes to the water unless so hard pressed by its pursuers as to be left without all other refuge. The noise they make is a faint bleat, querulous, but not easy to describe. They are sociable animals and unite in droves, sometimes to the number of fifty or sixty together; when they are seen playful and feeding on grass, which alone forms their food. At such time they move gently about like all other quadrupeds, on all fours; but at the slightest noise they spring up on their hind legs and sit erect, listening to what it may proceed from, and if it increases they bound off on those legs only, the fore ones at the same time being carried close to the breast like the paws of a monkey; and the tail stretched out, acts as a rudder on a ship. In drinking, the kangaroo laps. It is remarkable that they are never found in a fat state, being invariably lean. Of the flesh we always eat with avidity, but in Europe it would not be reckoned a delicacy. A rank flavour forms the principal objection to it. The tail is accounted the most delicious part, when stewed.

Hitherto I have spoken only of the large, or grey kangaroo, to which the natives give the name of patagaràn.*5 But there are (besides the kangaroo-rat) two other sorts. One of them we called the red kangaroo, from the colour of its fur, which is like that of a hare, and sometimes is mingled with a large portion of black: the natives call it bàgaray.†10 It rarely attains to more than forty pounds weight. The third sort is very rare, and in the formation of its head resembles the opossum. The kangaroo-rat is a small animal, never reaching, at its utmost growth, more than fourteen or fifteen pounds, and its usual size is not above seven or eight pounds. It joins to the head and bristles of a rat the leading distinctions of a kangaroo, by running when pursued on its hind legs only, and the female having a pouch. Unlike the kangaroo, who appears to have no fixed place of residence, this little animal constructs for itself a nest of grass, on the ground, of a circular figure, about ten inches in diameter, with a hole on one side for the creature to enter at; the inside being lined with a finer sort of grass, very soft and downy. But its manner of carrying the materials with which it builds the nest is the greatest curiosity: by entwining its tail (which, like that of all the kangaroo tribe, is long, flexible and muscular) around whatever it wants to remove, and thus dragging along the load behind it. This animal is good to eat; but whether it be more prolific at a birth than the kangaroo, I know not.

The Indians sometimes kill the kangaroo; but their greatest destroyer is the wild dog,*6 who feeds on them. Immediately on hearing or seeing this formidable enemy, the kangaroo flies to the thickest cover, in which, if he can involve himself, he generally escapes. In running to the cover, they always, if possible, keep in paths of their own forming, to avoid the high grass and stumps of trees which might be sticking up among it to wound them and impede their course.

Our methods of killing them were but two; either we shot them, or hunted them with greyhounds. We were never able to ensnare them. Those sportsmen who relied on the gun seldom met with success, unless they slept near covers, into which the kangaroos were wont to retire at night, and watched with great caution and vigilance when the game, in the morning, sallied forth to feed. They were, however, sometimes stolen in upon in the daytime; and that fascination of the eye, which has been by some authors so much insisted upon, so far acts on the kangaroo that if he fix his eye upon anyone, and no other object move at the same time, he will often continue motionless, in stupid gaze, while the sportsman advances with measured step towards him, until within reach of his gun. The greyhounds for a long time were incapable of taking them; but with a brace of dogs, if not near cover a kangaroo almost always falls, since the greyhounds have acquired by practice the proper method of fastening upon them. Nevertheless the dogs are often miserably torn by them. The rough wiry greyhound suffers least in the conflict, and is most prized by the hunters.

Other quadrupeds, besides the wild dog, consist only of the flying squirrel, of three kinds of opossums and some minute animals, usually marked by the distinction which so peculiarly characterises the opossum tribe. The rats, soon after our landing, became not only numerous but formidable, from the destruction they occasioned in the stores. Latterly they had almost disappeared, though to account for their absence were not easy. The first time Colbee saw a monkey, he called wurra (a rat), but on examining its paws he exclaimed with astonishment and affright, mulla (a man).

At the head of the birds the cassowary, or emu, stands conspicuous. The print of it which has already been given to the public is so accurate for the most part, that it would be malignant criticism in a work of this kind to point out a few trifling defects.

Here again naturalists must look forward to that information which longer and more intimate knowledge of the feathered tribe than I can supply, shall appear. I have nevertheless had the good fortune to see what was never seen but once, in the country I am describing, by Europeans—a hatch, or flock, of young cassowaries with the old bird.†11 I counted ten, but others said there were twelve. We came suddenly upon them, and they ran up a hill exactly like a flock of turkeys, but so fast that we could not get a shot at them. The largest cassowary ever killed in the settlement, weighed ninety-four pounds. Three young ones, which had been by accident separated from the dam, were at once taken and presented to the governor. They were not larger than so many pullets, although at first sight they appeared to be so from the length of their necks and legs. They were very beautifully striped, and from their tender state were judged to be not more than three or four days old. They lived only a few days.

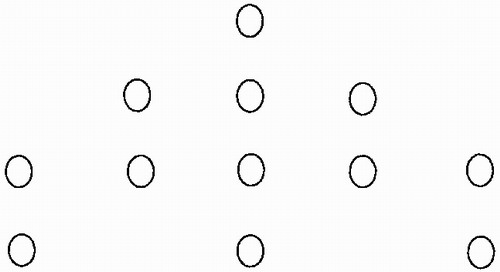

A single egg, the production of a cassowary, was picked up in a desert place, dropped on the sand, without covering or protection of any kind. Its form was nearly a perfect ellipsis; and the colour of the shell a dark green, full of little indents on its surface. It measured eleven inches and a half in circumference, five inches and a quarter in height, and weighed a pound and a quarter. Afterwards we had the good fortune to take a nest. It was found by a soldier in a sequestered solitary situation, made in a patch of lofty fern about three feet in diameter, rather of an oblong shape and composed of dry leaves and tops of fern stalks, very inartificially put together. The hollow in which lay the eggs, twelve in number, seemed made solely by the pressure of the bird. The eggs were regularly placed in the following position.

The soldier, instead of greedily plundering his prize, communicated the discovery to an officer, who immediately set out for the spot. When they had arrived there they continued for a long time to search in vain for their object, and the soldier was just about to be stigmatised with ignorance, credulity or imposture, when suddenly up started the old bird and the treasure was found at their feet.

The food of the cassowary is either grass, or a yellow bellflower growing in the swamps. It deserves remark that the natives deny the cassowary to be a bird, because it does not fly.

Of other birds the varieties are very numerous. Of the parrot tribe alone I could, while I am writing, count up from memory fourteen different sorts. Hawks are very numerous, so are quails. A single snipe has been shot. Ducks, geese and other aquatic birds are often seen in large flocks, but are universally so shy that it is found difficult to shoot them. Some of the smaller birds are very beautiful, but they are not remarkable for either sweetness or variety of notes. To one of them, not bigger than a tomtit, we have given the name of coach-whip, from its note exactly resembling the smack of a whip.†12 The country, I am of opinion, would abound with birds did not the natives, by perpetually setting fire to the grass and bushes, destroy the greater part of the nests; a cause which also contributes to render small quadrupeds scarce. They are besides ravenously fond of eggs and eat them whenever they find them. They call the roe of a fish and a bird’s egg by one name.

So much has been said of the abundance in which fish are found in the harbours of New South Wales that it looks like detraction to oppose a contradiction. Some share of knowledge may, however, be supposed to belong to experience. Many a night have I toiled (in the times of distress) on the public service, from four o’clock in the afternoon until eight o’clock next morning, hauling the seine in every part of the harbour of Port Jackson: and after a circuit of many miles and between twenty and thirty hauls, seldom more than a hundred pounds of fish were taken. However, it sometimes happens that a glut enters the harbour, and for a few days they sufficiently abound. But the universal voice of all professed fishermen is that they never fished in a country where success was so precarious and uncertain.

I shall not pretend to enumerate the variety of fish which are found. They are seen from a whale to a gudgeon. In the intermediate classes may be reckoned sharks of a monstrous size, skate, rock-cod, grey-mullet, bream, horse-mackerel, now and then a sole and john-dory, and innumerable others unknown in Europe, many of which are extremely delicious, and many highly beautiful. At the top of the list, as an article of food, stands a fish which we named light-horseman.†13 The relish of this excellent fish was increased by our natives, who pointed out to us its delicacies. No epicure in England could pick a head with more glee and dexterity than they do that of a light-horseman.

Reptiles in the swamps and covers are numerous. Of snakes there are two or three sorts: but whether the bite of any of them be mortal, or even venomous, is somewhat doubtful. I know but of one well attested instance of a bite being received from a snake. A soldier was bitten so as to draw blood, and the wound healed as a simple incision usually does without showing any symptom of malignity. A dog was reported to be bitten by a snake, and the animal swelled and died in great agony. But I will by no means affirm that the cause of his death was fairly ascertained. It is, however, certain that the natives show on all occasions the utmost horror of the snake, and will not eat it, although they esteem lizards, goannas and many other reptiles delicious fare. On this occasion they always observe that if the snake bites them, they become lame, but whether by this they mean temporary or lasting lameness I do not pretend to determine. I have often eaten snakes and always found them palatable and nutritive, though it was difficult to stew them to a tender state.

Summer here, as in all other countries, brings with it a long list of insects. In the neighbourhood of rivers and morasses, mosquitoes and sandflies are never wanting at any season, but at Sydney they are seldom numerous or troublesome. The most nauseous and destructive of all the insects is a fly which blows not eggs but large living maggots, and if the body of the fly be opened it is found full of them. Of ants there are several sorts, one of which bites very severely. The white ant is sometimes seen. Spiders are large and numerous. Their webs are not only the strongest, but the finest and most silky I ever felt. I have often thought their labour might be turned to advantage. It has, I believe, been proved that spiders, were it not for their quarrelsome disposition which irritates them to attack and destroy each other, might be employed more profitably than silk-worms.

The hardiness of some of the insects deserves to be mentioned. A beetle was immersed in proof spirits for four hours, and when taken out crawled away almost immediately. It was a second time immersed, and continued in a glass of rum for a day and a night, at the expiration of which period it still showed symptoms of life. Perhaps, however, what I from ignorance deem wonderful is common.

*

The last but the most important production yet remains to be considered. Whether plodding in London, reeking with human blood in Paris or wandering amidst the solitary wilds of New South Wales—Man is ever an object of interest, curiosity and reflection.

The natives around Port Jackson are in person rather more diminutive and slighter made, especially about the thighs and legs, than the Europeans. It is doubtful whether their society contained a person of six feet high. The tallest I ever measured reached five feet eleven inches, and men of his height were rarely seen. Baneelon, who towered above the majority of his countrymen, stood barely five feet eight inches high. His other principal dimensions were as follows:

Instances of natural deformity are scarce, nor did we ever see one of them left-handed. They are, indeed, nearly ambidexter; but the sword, the spear and the fish-gig are always used with the right hand. Their muscular force is not great; but the pliancy of their limbs renders them very active. ‘Give to civilised man all his machines, and he is superior to the savage; but without these, how inferior is he found on opposition, even more so than the savage in the first instance.’ These are the words of Rousseau, and like many more of his positions must be received with limitation. Were an unarmed Englishman and an unarmed New Hollander to engage, the latter, I think, would fall.

Mr Cook seems inclined to believe the covering of their heads to be wool. But this is erroneous. It is certainly hair, which when regularly combed becomes soon nearly as flexible and docile as our own. Their teeth are not so white and good as those generally found in Indian nations, except in the children, but the inferiority originates in themselves. They bite sticks, stones, shells and all other hard substances indiscriminately with them, which quickly destroys the enamel and gives them a jagged and uneven appearance. A high forehead, with prominent overhanging eyebrows, is their leading characteristic, and when it does not operate to destroy all openness of countenance gives an air of resolute dignity to the aspect, which recommends, in spite of a true Negro nose, thick lips, and a wide mouth. The prominent shin bone, so invariably found in the Africans, is not, however, seen. But in another particular they are more alike. The rank offensive smell which disgusts so much in the Negro, prevails strongly among them when they are in their native state, but it wears off in those who have resided with us and have been taught habits of cleanliness. Their hands and feet are small,*7 especially the former.

Their eyes are full, black and piercing, but the almost perpetual strain in which the optic nerve is kept, by looking out for prey, renders their sight weak at an earlier age than we in general find ours affected. These large black eyes are universally shaded by the long thick sweepy eyelash, so much prized in appreciating beauty, that perhaps hardly any face is so homely which this aid cannot in some degree render interesting; and hardly any so lovely which, without it, bears not some trace of insipidity. Their tone of voice is loud but not harsh. I have in some of them found it very pleasing.

Longevity, I think, is seldom attained by them. Unceasing agitation wears out the animal frame and is unfriendly to length of days. We have seen them grey with age, but not old; perhaps never beyond sixty years. But, it may be said, the American Indian, in his undebauched state, lives to an advanced period. True, but he has his seasons of repose. He reaps his little harvest of maize and continues in idleness while it lasts. He kills the roebuck or the moose-deer, which maintains him and his family for many days, during which cessation the muscles regain their spring and fit him for fresh toils. Whereas every sun awakes the native of New South Wales (unless a whale be thrown upon the coast) to a renewal of labour, to provide subsistence for the present day.

The women are proportionally smaller than the men. I never measured but two of them, who were both, I think, about the medium height. One of them, a sister of Baneelon, stood exactly five feet two inches high. The other, named Gooreedeeàna, was shorter by a quarter of an inch.

But I cannot break from Gooreedeeana so abruptly. She belonged to the tribe of Cameragal and rarely came among us. One day, however, she entered my house to complain of hunger. She excelled in beauty all their females I ever saw. Her age about eighteen, the firmness, the symmetry and the luxuriancy of her bosom might have tempted painting to copy its charms. Her mouth was small and her teeth, though exposed to all the destructive purposes to which they apply them, were white, sound and unbroken. Her countenance, though marked by some of the characteristics of her native land, was distinguished by a softness and sensibility unequalled in the rest of her countrywomen, and I was willing to believe that these traits indicated the disposition of her mind. I had never before seen this elegant timid female, of whom I had often heard; but the interest I took in her led me to question her about her husband and family. She answered me by repeating a name which I have now forgotten, and told me she had no children. I was seized with a strong propensity to learn whether the attractions of Gooreedeeana were sufficiently powerful to secure her from the brutal violence with which the women are treated, and as I found my question either ill-understood or reluctantly answered, I proceeded to examine her head, the part on which the husband’s vengeance generally alights. With grief I found it covered by contusions and mangled by scars. The poor creature, grown by this time more confident from perceiving that I pitied her, pointed out a wound just above her left knee which she told me was received from a spear, thrown at her by a man who had lately dragged her by force from her home to gratify his lust. I afterwards observed that this wound had caused a slight lameness and that she limped in walking. I could only compassionate her wrongs and sympathise in her misfortunes. To alleviate her present sense of them, when she took her leave I gave her, however, all the bread and salt pork which my little stock afforded.

After this I never saw her but once, when I happened to be near the harbour’s mouth in a boat with Captain Ball. We met her in a canoe with several more of her sex. She was painted for a ball, with broad stripes of white earth from head to foot, so that she no longer looked like the same Gooreedeeana. We offered her several presents, all of which she readily accepted; but finding our eagerness and solicitude to inspect her, she managed her canoe with such address as to elude our too near approach, and acted the coquet to admiration.

To return from this digression to my subject, I have only farther to observe that the estimation of female beauty among the natives (the men at least) is in this country the same as in most others. Were a New Hollander to portray his mistress, he would draw her the Venus aux belles fesses.†14 Whenever Baneelon described to us his favourite fair, he always painted her in this, and another particular, as eminently luxuriant.

Unsatisfied, however, with natural beauty (like the people of all other countries) they strive by adscititious embellishments to heighten attraction, and often with as little success. Hence the naked savage of New South Wales pierces the septum of his nose, through which he runs a stick or a bone, and scarifies his body, the charms of which increase in proportion to the number and magnitude of seams by which it is distinguished. The operation is performed by making two longitudinal incisions with a sharpened shell, and afterwards pinching up with the nails the intermediate space of skin and flesh, which thereby becomes considerably elevated and forms a prominence as thick as a man’s finger. No doubt but pain must be severely felt until the wound be healed. But the love of ornament defies weaker considerations, and no English beau can bear more stoutly the extraction of his teeth to make room for a fresh set from a chimney sweeper, or a fair one suffer her tender ears to be perforated, with more heroism than the grisly nymphs on the banks of Port Jackson, submit their sable shoulders to the remorseless lancet.

That these scarifications are intended solely to increase personal allurement I will not, however, positively affirm. Similar, perhaps, to the cause of an excision of part of the little finger of the left hand in the women, and of a front tooth in the men;*8 or probably after all our conjectures, superstitious ceremonies by which they hope either to avert evil or to propagate good, are intended. The colours with which they besmear the bodies of both sexes possibly date from the same common origin. White paint is strictly appropriate to the dance. Red seems to be used on numberless occasions, and is considered as a colour of less consequence. It may be remarked that they translate the epithet white when they speak of us, not by the name which they assign to this white earth, but by that with which they distinguish the palms of their hands.

As this leads to an important subject I shall at once discuss it. ‘Have these people any religion: any knowledge of, or believe in a deity?—any conception of the immortality of the soul?’ are questions which have been often put to me since my arrival in England. I shall endeavour to answer them with candour and seriousness.

Until belief be enlightened by revelation and chastened by reason, religion and superstition are terms of equal import. One of our earliest impressions is the consciousness of a superior power. The various forms under which this impression has manifested itself are objects of the most curious speculation.

The native of New South Wales believes that particular aspects and appearances of the heavenly bodies predict good or evil consequences to himself and his friends. He oftentimes calls the sun and moon ‘weeree,’ that is, malignant, pernicious. Should he see the leading fixed stars (many of which he can call by name) obscured by vapours, he sometimes disregards the omen, and sometimes draws from it the most dreary conclusions. I remember Abaroo running into a room where a company was assembled, and uttering frightful exclamations of impending mischiefs about to light on her and her countrymen. When questioned on the cause of such agitation she went to the door and pointed to the skies, saying that whenever the stars wore that appearance, misfortunes to the natives always followed. The night was cloudy and the air disturbed by meteors. I have heard many more of them testify similar apprehensions.

However involved in darkness and disfigured by error such a belief be, no one will, I presume, deny that it conveys a direct implication of superior agency; of a power independent of and uncontrolled by those who are the objects of its vengeance. But proof stops not here. When they hear the thunder roll and view the livid glare, they flee them not, but rush out and deprecate destruction. They have a dance and a song appropriated to this awful occasion, which consist of the wildest and most uncouth noises and gestures. Would they act such a ceremony did they not conceive that either the thunder itself, or he who directs the thunder, might be propitiated by its performance? That a living intellectual principle exists, capable of comprehending their petition and of either granting or denying it? They never address prayers to bodies which they know to be inanimate, either to implore their protection or avert their wrath. When the gum-tree in a tempest nods over them; or the rock overhanging the cavern in which they sleep threatens by its fall to crush them, they calculate (as far as their knowledge extends) on physical principles, like other men, the nearness and magnitude of the danger, and flee it accordingly. And yet there is reason to believe that from accidents of this nature they suffer more than from lightning. Baneelon once showed us a cave, the top of which had fallen in and buried under its ruins seven people who were sleeping under it.

To descend; is not even the ridiculous superstition of Colbee related in one of our journeys to the Hawkesbury? And again the following instance. Abaroo was sick. To cure her, one of her own sex slightly cut her on the forehead, in a perpendicular direction with an oyster shell, so as just to fetch blood. She then put one end of a string to the wound and, beginning to sing, held the other end to her own gums, which she rubbed until they bled copiously. This blood she contended was the blood of the patient, flowing through the string, and that she would thereby soon recover. Abaroo became well, and firmly believed that she owed her cure to the treatment she had received. Are not these, I say, links, subordinate ones indeed, of the same golden chain? He who believes in magic confesses supernatural agency, and a belief of this sort extends farther in many persons than they are willing to allow. There have lived men so inconsistent with their own principles as to deny the existence of a God, who have nevertheless turned pale at the tricks of a mountebank.

But not to multiply arguments on a subject where demonstration (at least to me) is incontestable, I shall close by expressing my firm belief that the Indians of New South Wales acknowledge the existence of a superintending deity. Of their ideas of the origin and duration of his existence; of his power and capacity; of his benignity or maleficence; or of their own emanation from him, I pretend not to speak. I have often, in common with others, tried to gain information from them on this head; but we were always repulsed by obstacles which we could neither pass by or surmount. Mr Dawes attempted to teach Abaroo some of our notions of religion, and hoped that she would thereby be induced to communicate hers in return. But her levity and love of play in a great measure defeated his efforts, although everything he did learn from her served to confirm what is here advanced. It may be remarked, that when they attended at church with us (which was a common practice) they always preserved profound silence and decency, as if conscious that some religious ceremony on our side was performing.

The question of whether they believe in the immortality of the soul will take up very little time to answer. They are universally fearful of spirits.*9 They call a spirit mawn. They often scruple to approach a corpse, saying that the mawn will seize them and that it fastens upon them in the night when asleep.*10 When asked where their deceased friends are they always point to the skies. To believe in after-existence is to confess the immortality of some part of being. To enquire whether they assign a limited period to such future state would be superfluous. This is one of the subtleties of speculation which a savage may be supposed not to have considered, without impeachment either of his sagacity or happiness.

Their manner of interring the dead has been amply described. It is certain that instead of burying they sometimes burn the corpse; but the cause of distinction we know not. A dead body, covered by a canoe, at whose side a sword and shield were placed in state, was once discovered. All that we could learn about this important personage was that he was a Gweeagal (one of the tribe of Gweea) and a celebrated warrior.

To appreciate their general powers of mind is difficult. Ignorance, prejudice, the force of habit, continually interfere to prevent dispassionate judgment. I have heard men so unreasonable as to exclaim at the stupidity of these people for not comprehending what a small share of reflection would have taught them they ought not to have expected. And others again I have heard so sanguine in their admiration as to extol for proofs of elevated genius what the commonest abilities were capable of executing.

If they be considered as a nation whose general advancement and acquisitions are to be weighed, they certainly rank very low, even in the scale of savages. They may perhaps dispute the right of precedency with the Hottentots or the shivering tribes who inhabit the shores of Magellan. But how inferior do they show when compared with the subtle African; the patient watchful American; or the elegant timid islander of the South Seas. Though suffering from the vicissitudes of their climate, strangers to clothing, though feeling the sharpness of hunger and knowing the precariousness of supply from that element on whose stores they principally depend, ignorant of cultivating the earth—a less enlightened state we shall exclaim can hardly exist.

But if from general view we descend to particular inspection, and examine individually the persons who compose this community, they will certainly rise in estimation. In the narrative part of this work I have endeavoured rather to detail information than to deduce conclusions, leaving to the reader the exercise of his own judgment. The behaviour of Arabanoo, of Baneelon, of Colbee and many others is copiously described, and assuredly he who shall make just allowance for uninstructed nature will hardly accuse any of those persons of stupidity or deficiency of apprehension.

To offer my own opinion on the subject, I do not hesitate to declare that the natives of New South Wales possess a considerable portion of that acumen, or sharpness of intellect, which bespeaks genius. All savages hate toil and place happiness in inaction, and neither the arts of civilised life can be practised or the advantages of it felt without application and labour. Hence they resist knowledge and the adoption of manners and customs differing from their own. The progress of reason is not only slow, but mechanical. ‘De toutes les instructions propres à l’homme, celle qu’il acquiert le plus tard, et le plus difficilement, est la raison meme.’†15 The tranquil indifference and unenquiring eye with which they surveyed our works of art have often, in my hearing, been stigmatised as proofs of stupidity and want of reflection. But surely we should discriminate between ignorance and defect of understanding. The truth was, they often neither comprehended the design nor conceived the utility of such works, but on subjects in any degree familiarised to their ideas, they generally testified not only acuteness of discernment but a large portion of good sense. I have always thought that the distinctions they showed in their estimate of us, on first entering into our society, strongly displayed the latter quality. When they were led into our respective houses, at once to be astonished and awed by our superiority, their attention was directly turned to objects with which they were acquainted. They passed without rapture or emotion our numerous artifices and contrivances, but when they saw a collection of weapons of war or of the skins of animals and birds, they never failed to exclaim, and to confer with each other on the subject. The master of that house became the object of their regard, as they concluded he must be either a renowned warrior, or an expert hunter.

Our surgeons grew into their esteem from a like cause. In a very early stage of intercourse, several natives were present at the amputation of a leg. When they first penetrated the intention of the operator, they were confounded, not believing it possible that such an operation could be performed without loss of life, and they called aloud to him to desist; but when they saw the torrent of blood stopped, the vessels taken up and the stump dressed, their horror and alarm yielded to astonishment and admiration, which they expressed by the loudest tokens. If these instances bespeak not nature and good sense, I have yet to learn the meaning of the terms.

If it be asked why the same intelligent spirit which led them to contemplate and applaud the success of the sportsman and the skill of the surgeon, did not equally excite them to meditate on the labours of the builder and the ploughman, I can only answer, that what we see in its remote cause is always more feebly felt than that which presents to our immediate grasp both its origin and effect.

Their leading good and bad qualities I shall concisely touch upon. Of their intrepidity no doubt can exist. Their levity, their fickleness, their passionate extravagance of character, cannot be defended. They are indeed sudden and quick in quarrel; but if their resentment be easily roused, their thirst of revenge is not implacable. Their honesty, when tempted by novelty, is not unimpeachable; but in their own society there is good reason to believe that few breaches of it occur. It were well if similar praise could be given to their veracity: but truth they neither prize nor practice. When they wish to deceive they scruple not to utter the grossest and most hardened lies.*11 Their attachment and gratitude to those among us whom they have professed to love have always remained inviolable, unless effaced by resentment, from sudden provocation: then, like all other Indians, the impulse of the moment is alone regarded by them.

Some of their manufactures display ingenuity, when the rude tools with which they work and their celerity of execution are considered. The canoes, fish-gigs, swords, shields, spears, throwing-sticks, clubs and hatchets, are made by the men. To the women are committed the fishing-lines, hooks and nets. As very ample collections of all these articles are to be found in many museums in England, I shall only briefly describe the way in which the most remarkable of them are made. The fishgigs and spears are commonly (but not universally) made of the long spiral shoot which arises from the top of the yellow gumtree, and bears the flower. The former have several prongs, barbed with the bone of kangaroo. The latter are sometimes barbed with the same substance, or with the prickle of the stingray, or with stone or hardened gum, and sometimes simply pointed. Dexterity in throwing and parrying the spear is considered as the highest acquirement. The children of both sexes practise from the time that they are able to throw a rush; their first essay. It forms their constant recreation. They afterwards heave at each other with pointed twigs. He who acts on the defensive holds a piece of new soft bark in the left hand, to represent a shield, in which he receives the darts of the assailant, the points sticking in it. Now commences his turn. He extracts the twigs and darts them back at the first thrower, who catches them similarly. In warding off the spear they never present their front, but always turn their side, their head at the same time just clear of the shield, to watch the flight of the weapon; and the body covered. If a spear drop from them when thus engaged, they do not stoop to pick it up, but hook it between the toes and so lift it until it meet the hand. Thus the eye is never diverted from its object, the foe. If they wish to break a spear or any wooden substance, they lay it not across the thigh or the body, but upon the head, and press down the ends until it snap. Their shields are of two sorts. That called ileemon is nothing but a piece of bark with a handle fixed in the inside of it. The other, dug out of solid wood, is called aragoòn and is made as follows, with great labour. On the bark of a tree they mark the size of the shield, then dig the outline as deep as possible in the wood with hatchets, and lastly flake it off as thick as they can, by driving in wedges. The sword is a large heavy piece of wood, shaped like a sabre, and capable of inflicting a mortal wound. In using it they do not strike with the convex side, but with the concave one, and strive to hook in their antagonists so as to have them under their blows. The fishinglines are made of the bark of a shrub. The women roll shreds of this on the inside of the thigh, so as to twist it together, carefully inserting the ends of every fresh piece into the last made. They are not as strong as lines of equal size formed of hemp. The fish-hooks are chopped with a stone out of a particular shell, and afterwards rubbed until they become smooth. They are very much curved, and not barbed. Considering the quickness with which they are finished, the excellence of the work, if it be inspected, is admirable. In all these manufactures the sole of the foot is used both by men and women as a work-board. They chop a piece of wood, or aught else upon it, even with an iron tool, without hurting themselves. It is indeed nearly as hard as the hoof of an ox.

Their method of procuring fire is this. They take a reed and shave one side of the surface flat. In this they make a small incision to reach the pith, and introducing a stick, purposely blunted at the end, into it, turn it round between the hands (as chocolate is milled) as swiftly as possible, until flame be produced. As this operation is not only laborious, but the effect tedious, they frequently relieve each other at the exercise. And to avoid being often reduced to the necessity of putting it in practice, they always, if possible, carry a lighted stick with them, whether in their canoes or moving from place to place on land.

Their treatment of wounds must not be omitted. A doctor is, with them, a person of importance and esteem, but his province seems rather to charm away occult diseases than to act the surgeon’s part, which, as a subordinate science, is exercised indiscriminately. Their excellent habit of body,*12 the effect of drinking water only, speedily heals wounds without an exterior application which with us would take weeks or months to close. They are, nevertheless, sadly tormented by a cutaneous eruption, but we never found it contagious. After receiving a contusion, if the part swell they fasten a ligature very tightly above it, so as to stop all circulation. Whether to this application, or to their undebauched habit, it be attributable, I know not, but it is certain that a disabled limb among them is rarely seen, although violent inflammations from bruises, which in us would bring on a gangrene, daily happen. If they get burned, either from rolling into the fire when asleep, or from the flame catching the grass on which they lie (both of which are common accidents) they cover the part with a thin paste of kneaded clay, which excludes the air and adheres to the wound until it be cured, and the eschar falls off.

Their form of government, and the detail of domestic life, yet remain untold. The former cannot occupy much space. Without distinctions of rank, except those which youth and vigour confer, there is strictly a system of equality attended with only one inconvenience—the strong triumph over the weak. Whether any laws exist among them for the punishment of offences committed against society; or whether the injured party in all cases seeks for relief in private revenge, I will not positively affirm; though I am strongly inclined to believe that only the latter method prevails. I have already said that they are divided into tribes; but what constitutes the right of being enrolled in a tribe, or where exclusion begins and ends, I am ignorant. The tribe of Cameragal is of all the most numerous and powerful. Their superiority probably arose from possessing the best fishing ground, and perhaps from their having suffered less from the ravages of the smallpox.

In their domestic detail there may be novelty, but variety is unattainable. One day must be very like another in the life of a savage. Summoned by the calls of hunger and the returning light, he starts from his beloved indolence, and snatching up the remaining brand of his fire, hastens with his wife to the strand to commence their daily task. In general the canoe is assigned to her, into which she puts the fire and pushes off into deep water, to fish with hook and line, this being the province of the women. If she have a child at the breast, she takes it with her. And thus in her skiff, a piece of bark tied at both ends with vines, and the edge of it but just above the surface of the water, she pushes out regardless of the elements, if they be but commonly agitated. While she paddles to the fishing-bank, and while employed there, the child is placed on her shoulders, entwining its little legs around her neck and closely grasping her hair with its hands. To its first cries she remains insensible, as she believes them to arise only from the inconveniency of a situation, to which she knows it must be inured. But if its plaints continue, and she supposes it to be in want of food, she ceases her fishing and clasps it to her breast. An European spectator is struck with horror and astonishment at their perilous situation, but accidents seldom happen. The management of the canoe alone appears a work of unsurmountable difficulty, its breadth is so inadequate to its length. The Indians, aware of its ticklish formation, practise from infancy to move in it without risk. Use only could reconcile them to the painful position in which they sit in it. They drop in the middle of the canoe upon their knees, and resting the buttocks on the heels, extend the knees to the sides, against which they press strongly so as to form a poise sufficient to retain the body in its situation, and relieve the weight which would otherwise fall wholly upon the toes. Either in this position or cautiously moving in the centre of the vessel, the mother tends her child, keeps up her fire (which is laid on a small patch of earth), paddles her boat, broils fish and provides in part the subsistence of the day. Their favourite bait for fish is a cockle.

The husband in the meantime warily moves to some rock, over which he can peep into unruffled water to look for fish. For this purpose he always chooses a weather shore, and the various windings of the numerous creeks and indents always afford one. Silent and watchful, he chews a cockle and spits it into the water. Allured by the bait, the fish appear from beneath the rock. He prepares his fish-gig, and pointing it downward, moves it gently towards the object, always trying to approach it as near as possible to the fish before the stroke be given. At last he deems himself sufficiently advanced and plunges it at his prey. If he has hit his mark, he continues his efforts and endeavours to transpierce it or so to entangle the barbs in the flesh as to prevent its escape. When he finds it secure he drops the instrument, and the fish, fastened on the prongs, rises to the surface, floated by the buoyancy of the staff. Nothing now remains to be done but to haul it to him, with either a long stick or another fish-gig (for an Indian, if he can help it, never goes into the water on these occasions) to disengage it, and to look out for fresh sport.

But sometimes the fish have either deserted the rocks for deeper water, or are too shy to suffer approach. He then launches his canoe, and leaving the shore behind, watches the rise of prey out of the water, and darts his gig at them to the distance of many yards. Large fish he seldom procures by this method; but among shoals of mullets, which are either pursued by enemies, or leap at objects on the surface, he is often successful. Baneelon has been seen to kill more than twenty fish by this method in an afternoon. The women sometimes use the gig, and always carry one in each canoe to strike large fish which may be hooked and thereby facilitate the capture. But generally speaking, this instrument is appropriate to the men, who are never seen fishing with the line, and would indeed consider it as a degradation of their pre-eminence.

When prevented by tempestuous weather or any other cause, from fishing, these people suffer severely. They have then no resource but to pick up shellfish, which may happen to cling to the rocks and be cast on the beach, to hunt particular reptiles and small animals, which are scarce, to dig fern root in the swamps or to gather a few berries, destitute of flavour and nutrition, which the woods afford. To alleviate the sensation of hunger, they tie a ligature tightly around the belly, as I have often seen our soldiers do from the same cause.

Let us, however, suppose them successful in procuring fish. The wife returns to land with her booty, and the husband quitting the rock joins his stock to hers, and they repair either to some neighbouring cavern or to their hut. This last is composed of pieces of bark, very rudely piled together, in shape as like a soldier’s tent as any known image to which I can compare it: too low to admit the lord of it to stand upright, but long and wide enough to admit three or four persons to lie under it. ‘Here shelters himself a being, born with all those powers which education expands, and all those sensations which culture refines.’†16 With a lighted stick brought from the canoe they now kindle a small fire at the mouth of the hut and prepare to dress their meal. They begin by throwing the fish, exactly in the state in which it came from the water, on the fire. When it has become a little warmed they take it off, rub away the scales, and then peel off with their teeth the surface, which they find done, and eat. Now, and not before, they gut it; but if the fish be a mullet or any other which has a fatty substance about the intestines, they carefully guard that part and esteem it a delicacy. The cooking is now completed by the remaining part being laid on the fire until it be sufficiently done. A bird, a lizard, a rat, or any other animal, they treat in the same manner. The feathers of the one and the fur of the other, they thus get rid of.*13

Unless summoned away by irresistible necessity, sleep always follows the repast. They would gladly prolong it until the following day; but the canoe wants repair, the fish-gig must be barbed afresh, new lines must be twisted and new hooks chopped out. They depart to their respective tasks, which end only with the light.

Such is the general life of an Indian. But even he has his hours of relaxation, in seasons of success, when fish abounds. Wanton with plenty, he now meditates an attack upon the chastity of some neighbouring fair one; and watching his opportunity he seizes her and drags her way to complete his purpose. The signal of war is lighted; her lover, her father, her brothers, her tribe, assemble, and vow revenge on the spoiler. He tells his story to his tribe. They judge the case to be a common one and agree to support him. Battle ensues; they discharge their spears at each other, and legs and arms are transpierced. When the spears are expended the combatants close and every species of violence is practised. They seize their antagonist and snap like enraged dogs, they wield the sword and club, the bone shatters beneath their fall and they drop the prey of unsparing vengeance.

Too justly, as my observations teach me, has Hobbes defined a state of nature to be a state of war. In the method of waging it among these people, one thing should not, however, escape notice. Unlike all other Indians, they never carry on operations in the night, or seek to destroy by ambush and surprise. Their ardent fearless character seeks fair and open combat only.

But enmity has its moments of pause. Then they assemble to sing and dance. We always found their songs disagreeable from their monotony. They are numerous, and vary both in measure and time. They have songs of war, of hunting, of fishing, for the rise and set of the sun, for rain, for thunder and for many other occasions. One of these songs, which may be termed a speaking pantomime, recites the courtship between the sexes and is accompanied with acting highly expressive. I once heard and saw Nanbaree and Abaroo perform it. After a few preparatory motions she gently sunk on the ground, as if in a fainting fit. Nanbaree, applying his mouth to her ear, began to whisper in it, and baring her bosom, breathed on it several times. At length, the period of the swoon having expired, with returning animation she gradually raised herself. She now began to relate what she had seen in her vision, mentioning several of her countrymen by name, whom we knew to be dead; mixed with other strange incoherent matter, equally new and inexplicable, though all tending to one leading point—the sacrifice of her charms to her lover.

At their dances I have often been present; but I confess myself unable to convey in description an accurate account of them. Like their songs, they are conceived to represent the progress of the passions and the occupations of life. Full of seeming confusion, yet regular and systematic, their wild gesticulations and frantic distortions of body are calculated rather to terrify, than delight, a spectator. These dances consist of short parts, or acts, accompanied with frequent vociferations and a kind of hissing or whizzing noise. They commonly end with a loud rapid shout, and after a short respite are renewed. While the dance lasts, one of them (usually a person of note and estimation) beats time with a stick on a wooden instrument held in the left hand, accompanying the music with his voice; and the dancers sometimes sing in concert.

I have already mentioned that white is the colour appropriated to the dance, but the style of painting is left to everyone’s fancy. Some are streaked with waving lines from head to foot; others marked by broad cross-bars, on the breast, back and thighs, or encircled with spiral lines, or regularly striped like a zebra. Of these ornaments, the face never wants its share, and it is hard to conceive anything in the shape of humanity more hideous and terrific than they appear to a stranger—seen, perhaps, through the livid gleam of a fire, the eyes surrounded by large white circles, in contrast with the black ground, the hair stuck full of pieces of bone and in the hand a grasped club, which they occasionally brandish with the greatest fierceness and agility. Some dances are performed by men only, some by women only, and in others the sexes mingle. In one of them I have seen the men drop on their hands and knees and kiss the earth with the greatest fervour, between the kisses looking up to Heaven. They also frequently throw up their arms, exactly in the manner in which the dancers of the Friendly Islands are depicted in one of the plates of Mr Cook’s last voyage.†17

Courtship here, as in other countries, is generally promoted by this exercise, where everyone tries to recommend himself to attention and applause. Dancing not only proves an incentive, but offers an opportunity in its intervals. The first advances are made by the men, who strive to render themselves agreeable to their favourites by presents of fishing-tackle and other articles which they know will prove acceptable. Generally speaking, a man has but one wife; but infidelity on the side of the husband, with the unmarried girls, is very frequent. For the most part, perhaps, they intermarry in their respective tribes. This rule is not, however, constantly observed, and there is reason to think that a more than ordinary share of courtship and presents, on the part of the man, is required in this case. Such difficulty seldom operates to extinguish desire, and nothing is more common than for the unsuccessful suitor to ravish by force that which he cannot accomplish by entreaty. I do not believe that very near connexions by blood ever cohabit. We knew of no instance of it.

But indeed the women are in all respects treated with savage barbarity. Condemned not only to carry the children but all other burthens, they meet in return for submission only with blows, kicks and every other mark of brutality. When an Indian is provoked by a woman, he either spears her or knocks her down on the spot. On this occasion he always strikes on the head, using indiscriminately a hatchet, a club or any other weapon which may chance to be in his hand. The heads of the women are always consequently seen in the state which I found that of Gooreedeeana. Colbee, who was certainly in other respects a good tempered merry fellow, made no scruple of treating Daringa, who was a gentle creature, thus. Baneelon did the same to Barangaroo, but she was a scold and a vixen, and nobody pitied her. It must nevertheless be confessed that the women often artfully study to irritate and inflame the passions of the men, although sensible that the consequence will alight on themselves.

Many a matrimonial scene of this sort have I witnessed. Lady Mary Wortley Montague, in her sprightly letters from Turkey, longs for some of the advocates for passive obedience and unconditional submission then existing in England to be present at the sights exhibited in a despotic government. A thousand times, in like manner, have I wished that those European philosophers whose closest speculations exalt a state of nature above a state of civilisation, could survey the phantom which their heated imaginations have raised. Possibly they might then learn that a state of nature is, of all others, least adapted to promote the happiness of a being capable of sublime research and unending ratiocination. That a savage roaming for prey amidst his native deserts is a creature deformed by all those passions which afflict and degrade our nature, unsoftened by the influence of religion, philosophy and legal restriction: and that the more men unite their talents, the more closely the bands of society are drawn and civilisation advanced, inasmuch is human felicity augmented, and man fitted for his unalienable station in the universe.

Of the language of New South Wales I once hoped to have subjoined to this work such an exposition as should have attracted public notice and have excited public esteem. But the abrupt departure of Mr Dawes, who, stimulated equally by curiosity and philanthropy, had hardly set foot on his native country when he again quitted it to encounter new perils in the service of the Sierra Leona company, precludes me from executing this part of my original intention, in which he had promised to co-operate with me; and in which he had advanced his research beyond the reach of competition. The few remarks which I can offer shall be concisely detailed.

We were at first inclined to stigmatise this language as harsh and barbarous in its sounds. Their combinations of words in the manner they utter them frequently convey such an effect. But if not only their proper names of men and places, but many of their phrases and a majority of their words, be simply and unconnectedly considered, they will be found to abound with vowels and to produce sounds sometimes mellifluous, and sometimes sonorous. What ear can object to the names of Còlbee (pronounced exactly as Colby is with us), Bèreewan, Bòndel, Imèerawanyee, Deedòra, Wòlarawaree, or Bàneelon, among the men; or to Wereewèea, Gòoreedeeana, Milba,*14 or Matilba, among the women. Parramàtta, Gwèea, Càmeera, Càdi, and Memel, are names of places. The tribes derive their appellations from the places they inhabit. Thus Càmeragal means the men who reside in the bay of Cameera; Càdigal, those who reside in the bay of Cadi; and so of the others. The women of the tribe are denoted by adding eean to any of the foregoing words. A Cadigalèean imports a woman living at Cadi, or of the tribe of Cadigal. These words, as the reader will observe, are accented either on the first syllable or the penultima. In general, however, they are partial to the emphasis being laid as near the beginning of the word as possible.

Of compound words they seem fond. Two very striking ones appear in the journal to the Hawkesbury. Their translations of our words into their language are always apposite, comprehensive, and drawn from images familiar to them. A gun for instance they call goòroobeera, that is, a stick of fire. Sometimes also, by a licence of language, they call those who carry guns by the same name. But the appellation by which they generally distinguished us was that of bèreewolgal, meaning men come from afar. When they salute any one they call him damèeli, or namesake, a term which not only implies courtesy and goodwill, but a certain degree of affection in the speaker. An interchange of names with anyone is also a symbol of friendship. Each person has several names; one of which, there is reason to believe, is always derived from the first fish or animal which the child, in accompanying its father to the chase or a fishing, may chance to kill.

Not only their combinations, but some of their simple sounds, were difficult of pronunciation to mouths purely English. Diphthongs often occur. One of the most common is that of ‘ae’, or perhaps, ‘ai’, pronounced not unlike those letters in the French verb haïr, to hate. The letter ‘y’ frequently follows ‘d’ in the same syllable. Thus the word which signifies a woman is dyin; although the structure of our language requires us to spell it deein.

But if they sometimes put us to difficulty, many of our words were to them unutterable. The letters ‘s’ and ‘v’ they never could pronounce. The latter became invariably ‘w’, and the former mocked all their efforts, which in the instance of Baneelon has been noticed; and a more unfortunate defect in learning our language could not easily be pointed out.

They use the ellipsis in speaking very freely; always omitting as many words as they possibly can, consistent with being understood. They inflect both their nouns and verbs regularly; and denote the cases of the former and the tenses of the latter, not like the English by auxiliary words, but like the Latins by change of termination. Their nouns, whether substantive or adjective, seem to admit of no plural. I have heard Mr Dawes hint his belief of their using a dual number, similar to the Greeks, but I confess that I never could remark aught to confirm it. The method by which they answer a question that they cannot resolve is similar to what we sometimes use. Let for example the following question be put: Waw Colbee yagoono?— Where is Colbee today? Waw, baw!—Where, indeed! would be the reply. They use a direct and positive negative, but express the affirmative by a nod of the head or an inclination of the body.

Opinions have greatly differed whether or not their language be copious. In one particular it is notoriously defective. They cannot count with precision more than four. However as far as ten, by holding up the fingers, they can both comprehend others and explain themselves. Beyond four every number is called great; and should it happen to be very large, great great, which is an Italian idiom also. This occasions their computations of time and space to be very confused and incorrect. Of the former they have no measure but the visible diurnal motion of the sun or the monthly revolution of the moon.

To conclude the history of a people for whom I cannot but feel some share of affection. Let those who have been born in more favoured lands and who have profited by more enlightened systems, compassionate, but not despise their destitute and obscure situation. Children of the same omniscient paternal care, let them recollect that by the fortuitous advantage of birth alone they possess superiority: that untaught, unaccommodated man is the same in Pall Mall as in the wilderness of New South Wales. And ultimately let them hope and trust that the progress of reason and the splendour of revelation will in their proper and allotted season be permitted to illumine and transfuse into these desert regions, knowledge, virtue and happiness.